Abstract

Background/Aims:

To compare the efficacy and safety profile of doxorubicin-loaded drug-eluting beads (DEB) to the conventional TACE (C-TACE) in the management of nonresectable hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC).

Patients and Methods:

All patients with nonresectable HCC who underwent either c-TACE or DEB-TACE during the period 2006–2014 and fulfilled the inclusion criteria were included in this retrospective study. Primary endpoints were tumor response rate at first imaging follow up, treatment-related liver toxicity, and treatment emergent adverse events (TEAE).

Results:

Thirty-five patients (51 procedures) in the DEB-TACE group and 19 patients (25 procedures) in the c-TACE group were included in the analysis. The median follow up time was 61 days (range 24–538 days) in the DEB-TACE group and 86 days (range 3–152 days) for the c-TACE group patients. Complete response (CR), objective response (OR), disease control (DC), and progressive disease (PD) rates were 11%, 24%, 53%, and 47%, respectively, in the DEB = TACE group compared with 4%, 32%, 64%, and 36%, respectively, in the c-TACE group. Mean ALT change from baseline was minimal in the DEB-TACE patients compared with c-TACE group (7.2 vs 79.4 units, P = 0.001). Hospital stay was significantly shorter in the DEB-TACE group (7.8 days vs 11.4 days; P = 0.038). The 2-year survival rate was 60% for the c-TACE patients and 58% for the DEB-TACE (P = 0.4).

Conclusions:

DEB-TACE compared with c-TACE is associated with lesser liver toxicity benefit, better tolerance, and shorter hospital stay. The two modalities however had similar survival and efficacy benefits.

Keywords: Conventional transarterial chemoembolization, drug-eluting beads, hepatocellular carcinoma

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the most common primary liver malignancy. The incidence is increasing and is reported as the 6th most common cancer among men. HCC is the 3rd most common cause of cancer-related death among men and the sixth among women worldwide.[1] HCC lesions, unlike the normal liver tissue, are commonly hypervascular and their sole blood supply is derived from the hepatic arteries. Hence the benefit of hepatic artery embolization that can lead to selective necrosis of the liver tumor. The synergistic effect of embolization and conventional selective transarterial chemotherapy (c-TACE) results in further necrosis of the tumor; albeit at the cost of increased damage to the surrounding normal liver tissue as well as a higher incidence of chemotherapy-related systemic side effects.[2,3] These complications are collectively recognized as postembolization syndrome (PES), observed in approximately 60%–80% of patients.[4] The high incidence of PES following c-TACE prompted investigators to develop newer modalities that allow more controlled release of the cytotoxic agents into the HCC lesions and reduce the risk of PES. Preclinical experiments confirmed that binding drug-eluting beads (DEB) with anthracycline drugs such as doxorubicin was a suitable and effective method for delivering the chemotherapy to the tumor bed.[5,6] Clinical studies evaluating the safety of this method found that DEB-TACE offers a better safety profile with lower incidence of PES and drug-related systemic toxicity.[2,7,8,9,10] Several studies compared c-TACE to DEB-TACE including retrospective analyses and prospective randomized trials.[2,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19] Although these studies showed favorable safety profile and lower incidence of liver and systemic toxicity compared with c-TACE, the reported tumor response and survival benefit requires further systematic analysis to determine the comparative effectiveness of these treatment methods.

This study aims at comparing the efficacy and safety profile of DEB-TACE to C-TACE in the management of nonresectable HCC. Primary efficacy endpoint was tumor response rate at first follow up imaging using the modified Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (mRECIST). The primary safety endpoint was treatment-related liver toxicity and treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAE).

PATIENTS AND METHODS

This study retrospectively compares the efficacy and safety profile of DEB-TACE with that of C-TACE in the management of nonresectable HCC. The research and ethics committee at our institution approved this study.

All patients had clinical and laboratory evaluation as well as cross-sectional imaging with triphasic computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance (MR) of the liver prior to and following the procedure to assess for tumor response. Patients who lost to follow up or had no available proper pre- or postprocedural imaging were excluded from the study.

A multidisciplinary group decided the treatment plan in all patients after careful consideration of tumor stage, liver functions, and patient's physical status. All patients were older than 18 years and were diagnosed with uninodular or multinodular HCC. Lesions greater than 2 cm were deemed not accessible for locoregional treatment by ethanol injection or radiofrequency ablation (RFA) due to their unfavorable anatomic location.

Treatment protocols

TACE procedures were performed by the interventional radiologist through femoral artery approach in all patients. Superselective cannulation of the main feeders was performed using a microcatheter whenever possible. The c-TACE protocol consisted of intra-arterial infusion of cisplatin 50–100 mg mixed with lipiodol. The DEB-TACE protocol used DC beads (100–300 and 300–500 μm) (Biocompatibles, Surrey, UK) loaded with 75 mg of doxorubicin hydrochloride. To optimize visualization during the infusion procedure, the loaded beads were mixed with non-ionic water-soluble contrast and saline to a ratio of 8:2. The embolization endpoint was determined by obliteration of tumor blush and sluggish flow through the feeding arteries. If flow continued following the chemotherapy infusion, polyvinyl alcohol particles (355–500 μm) (Contour® PVA Embolization Particles, Boston Scientific, Natick, MA, USA) were injected to achieve complete stasis of the feeding vessels.

Efficacy evaluation

Tumor response was determined according to modified RECIST for HCC whereby complete response (CR) of the tumor was defined as the disappearance of any tumoral arterial enhancement at cross sectional imaging obtained after treatment. Partial response (PR) was considered as at least a 30% decrease in the sum of diameters of viable lesions compared to the pre-procedural sum of diameters of lesions. Progressive disease included an increase of at least 20% in the sum of the diameters of viable lesions. Stable disease was scored for any cases that did not qualify for either PR or progressive disease. Objective response (CR + PR) and disease control (DC = CR + PR + SD) were calculated and comparison between the two groups was conducted. Tumor response was evaluated following each procedure for both treated target and nontarget lesions. The interventional radiologist (MA with 6 years of experience) who was blinded to the clinical outcome and laboratory values, conducted the retrospective imaging evaluation. The final CT or MR report was reviewed in all cases to further confirm the findings.

Safety evaluation

All periprocedural adverse events were documented. Major and minor complications were defined according to the quality improvement guidelines for TACE.[20] Mild postembolization syndrome (PES) requiring no extended hospital stay was considered as an expected outcome rather than a complication. The primary safety endpoint was the incidence of treatment-related major complication and liver toxicity as evaluated by an increase in liver enzymes at the early assessment performed 24–48 h after the procedure.

Statistical analysis

Analysis of variables was performed on SPSS 17.0 software (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA) using the Chi-square test, t-test, or Fisher's exact test as appropriate. Nonparametric variables were analyzed with Mann–Whitney U test. A two-tailed P value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Patients’ characteristics

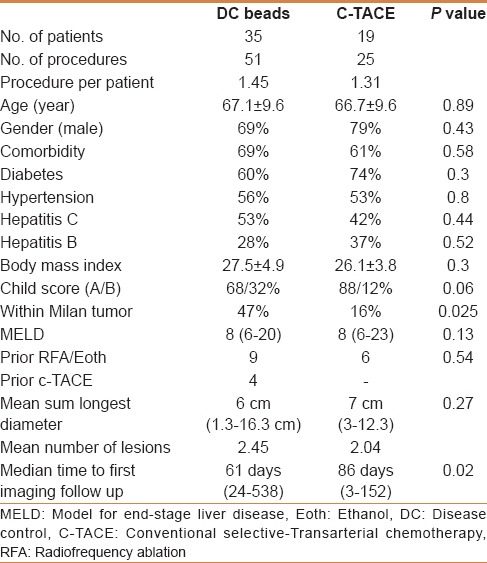

During the period from 2006 to 2014, 86 TACE procedures (c-TACE and DEB-TACE) were found in the hepatology and radiology registry. Ten procedures were excluded due to the lack of proper imaging evaluation prior to/or following the procedure. The study included a total of 54 Saudi patients (39 males and 16 females) with mean age of 67 years who underwent a total of 76 procedures (DEB-TACE = 51, c-TACE = 25). There was no statistical difference between the two study groups in the associated comorbidities or frequency of hepatitis C or B [Table 1]. There was tendency toward treating more patients with more advanced chronic liver disease (Child score B) by DEB-TACE (32%) compared with c-TACE (12%) but was not statistically significant (P = 0.06). Patients with Child C score were not considered for TACE treatment throughout the study period.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics

Locoregional treatment with RFA or ethanol injection was done in 15 patients (DEB-TACE = 9, c-TACE = 6). Four patients in the DEB-TACE were previously treated with c-TACE. Sixteen patients in the DEB-TACE group (46%) were within Milan criteria as compared with 3 (16%) in the c-TACE (P = 0.02). These patients were not candidate for transplant, surgical resection, or for locoregional treatment. There was no difference in the MELD score between the two groups (P = 0.13).

The mean sum longest diameter (SLD) in the DEB-TACE group was 6 cm and in the c-TACE group was 7 cm (P = 0.27). The mean number of lesions was 2.45 in DEB-TACE versus 2.04 in the c-TACE group [Table 1].

Efficacy analysis

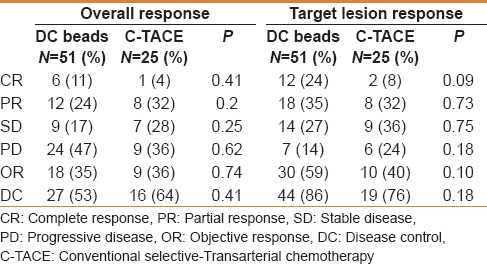

Tumor response evaluation was done using the mRECIST method at the first imaging follow-up after each procedure. The median follow-up time for the DEB-TACE group was 61 days (21–538 days) as compared with 86 days in the c-TACE patients (3–152 days) (P = 0.02). The overall tumor objective response and disease control inclusive of the target and nontarget lesions was not statistically different between the DEB-TACE and c-TACE [Table 2]. Evaluation of target lesion response following every treatment shows better objective response (59%) and disease control (86%) rates with DEB-TACE compared with c-TACE (OR = 40%, DC = 76%). However, this difference was not statistically significant.

Table 2.

Response rate based on modified RECIST criteria

Safety analysis

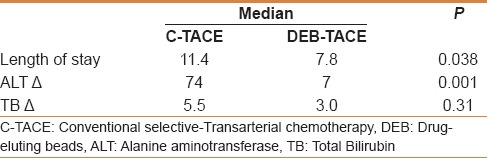

Patients who underwent DEB-TACE showed significantly less increase in ALT from baseline (mean change 7.2 units) compared with c-TACE patients (mean change 79.4 units) (P = 0.001). However, there was no significant difference in the total bilirubin change between the two groups.

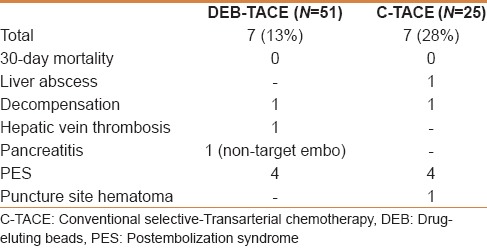

The DEB-TACE procedure was associated with significantly shorter hospital stay (7.8 days vs 11.4 days; P = 0.038) [Table 3]. No 30-day mortality was reported in each study arm. The overall complications rate was lower in the DEB-TACE group compared with the c-TACE group (28% vs 13%). Specifically, postembolization symptoms were less encountered following DEB-TACE (7%) compared with c-TACE (16%). A case of pancreatitis occurred following DEB-TACE was attributed to nontarget embolization. This resulted in a 5 cm pancreatic head pseudocyst and later obstructive jaundice and focal segmental cholangitis. None of the recognized systemic adverse events (eg, bone marrow suppression, alopecia, mucositis) were encountered in both treatment groups [Table 4].

Table 3.

Comparison between c-TACE and DEB-TACE groups in regard to length of stay and change in liver function tests

Table 4.

Rate of complications

Survival analysis

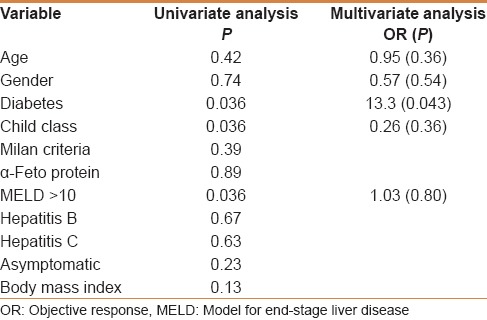

Survival data was available for 37 patients. Seventeen patients lost clinical follow up after the postprocedure imaging evaluation (c-TACE = 9, DEB-TACE = 8). All-cause mortality during the study was (c-TACE = 6, DEB-TACE = 5). There was no significant difference in the 2-year survival rate that was 60% for the c-TACE cohort and 58% for the DEB-TACE (P = 0.4). Univariate analysis showed that the most significant predictors of mortality in all patients are diabetes, Child–Pugh class and an MELD score greater than 10 [Table 5].

Table 5.

Univariate and multivariate analysis of variables as predictors of mortality

DISCUSSION

Transarterial chemoembolization has been widely used for the treatment of unresectable multinodular asymptomatic HCC tumors without vascular invasion or extrahepatic spread.[1,21,22] Although conventional TACE (c-TACE) allows delivery of high concentrations of the chemotherapeutic agents into the tumor; a significant proportion of the dose passes into the systemic circulation contributing to the postembolization syndrome (PES).[23,24] PES occurs in approximately 60%–80% of patients due to the embolization of the noninvolved liver tissue as well as the systemic effect of the infused chemotherapy.[4] Drug-eluting beads (DEB), designed to bind with anthracycline drugs such as doxorubicin, have been introduced for effective and perhaps safer delivery of the chemotherapeutic agent to the tumor bed.[2,5,6,7,8,9,10] When compared with c-TACE, DEB-TACE was shown to have better safety profile and lower incidence of liver and systemic toxicity.[2,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19] The Precision V randomized clinical trial (RCT) revealed a lower incidence of systemic side effects with DEB-TACE. Specifically, alopecia and marrow suppression were more common and of greater severity in c-TACE compared with DEB-TACE patients.[2] Regarding treating patients with portal vein thrombosis, several studies included patients with either bland or tumor portal vein thrombosis of variable extents including both segmental and main portal vein thrombosis.[11,13,18,19] Dhanasekaran et al. suggested that DEB-TACE could be administered safely in patients with portal vein thrombosis and Child A/B liver disease.[11] However, subgroup analysis showed that long-term survival was not statistically different between patients with patent and thrombosed portal veins treated with DEB-TACE.[11]

A meta-analysis of seven previous studies[2,11,12,15,17,19,25] by Gao et al. suggested that tumor response following DEB-TACE is the same with c-TACE.[26] However, the authors reported no safety or survival analysis in their review. Another meta-analysis showed that DEB-TACE is as safe as c-TACE and provided significantly better objective tumor response compared with c-TACE.[27] The 1- and 2-year survival is better with DEB-TACE.[27]

In our study, the overall response rate of both the target and the nontarget lesions was comparable between conventional and DEB-TACE. However, there was a nonstatistically significant trend toward improved response of target lesions with DEB-TACE. This suggests that DEB-TACE could be more effective in treating multifocal HCC if repeat sequential treatment is implemented at regular intervals. Unfortunately, this could not be achieved in majority of our patients due to irregularity of patients’ presentation to follow-up imaging and clinic encounters. Noteworthy is the significant difference in the time to first imaging follow-up between the two study groups, which may spuriously alter the tumor response outcome. It should also be considered that the hyperdense lipiodol might falsely mask any residual or recurrent enhancing tumor on the follow-up CT scan, whereas enhancing lesion can be easily detected in patients who received DEB-TACE due to the lack of adjacent hyperdensity. This may falsely improve the tumor response in c-TACE cases leading to undertreatment, and in turn may improve the patients’ outcome in DEB-TACE cases.

The overall complication rate was lower in the DEB-TACE group, particularly the incidence of PES. Furthermore, hospital stay was also significantly shorter following DEB-TACE, which indicates better tolerance of the treatment. This is in keeping with several previous studies comparing the treatment methods.[2,7,8,9,10] Our comparison also shows less elevation in ALT following DEB-TACE with a mean of 7.2 units, which is consistent with previous comparative studies.[2,14,15,17,19] Although the 2-year survival was not statistically different between the study groups, there was a trend for treating patients with more advanced liver disease with DEB-TACE suggesting better safety profile in this subset of patients. While survival benefit is not distinctly in favor of DEB-TACE,[11,14,16,28] particularly in advanced tumor stage or Child C class, the improved tolerance allows for delivering treatment more frequently, and perhaps with higher cumulative doses.[2,29]

Our study suffers several limitations including the retrospective nature and the discrepancy in sample size, some patients’ characteristics as well as the difference in follow-up time between the study arms. Although our analysis shows no survival benefit with DEB-TACE, it suggests that it is as effective as c-TACE in achieving tumor response.

DEB-TACE was better tolerated than c-TACE and allowed for a shorter hospital stay. It caused significantly lesser liver toxicity than c-TACE and potentially might allow for treating patients with more advanced liver disease.

The findings of our retrospective study invites for further evaluation of DEB-TACE by larger randomized clinical trials.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.European Association For The Study Of The Liver; European Organisation For Research And Treatment Of Cancer. EASL-EORTC clinical practice guidelines: Management of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 2012;56:908–43. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2011.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lammer J, Malagari K, Vogl T, Pilleul F, Denys A, Watkinson A, et al. Prospective randomized study of doxorubicin-eluting-bead embolization in the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma: Results of the PRECISION V study. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2010;33:41–52. doi: 10.1007/s00270-009-9711-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Malagari K, Pomoni M, Kelekis A, Pomoni A, Dourakis S, Spyridopoulos T, et al. Prospective randomized comparison of chemoembolization with doxorubicin-eluting beads and bland embolization with BeadBlock for hepatocellular carcinoma. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2010;33:541–51. doi: 10.1007/s00270-009-9750-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marelli L, Stigliano R, Triantos C, Senzolo M, Cholongitas E, Davies N, et al. Transarterial therapy for hepatocellular carcinoma: Which technique is more effective? A systematic review of cohort and randomized studies. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2007;30:6–25. doi: 10.1007/s00270-006-0062-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hong K, Khwaja A, Liapi E, Torbenson MS, Georgiades CS, Geschwind JF. New intra-arterial drug delivery system for the treatment of liver cancer: Preclinical assessment in a rabbit model of liver cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:2563–7. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-2225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lewis AL, Gonzalez MV, Lloyd AW, Hall B, Tang Y, Willis SL, et al. DC bead: In vitro characterization of a drug-delivery device for transarterial chemoembolization. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2006;17:335–42. doi: 10.1097/01.RVI.0000195323.46152.B3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Malagari K, Pomoni M, Spyridopoulos TN, Moschouris H, Kelekis A, Dourakis S, et al. Safety profile of sequential transcatheter chemoembolization with DC Bead: Results of 237 hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) patients. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2011;34:774–85. doi: 10.1007/s00270-010-0044-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Malagari K, Chatzimichael K, Alexopoulou E, Kelekis A, Hall B, Dourakis S, et al. Transarterial chemoembolization of unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma with drug eluting beads: Results of an open-label study of 62 patients. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2008;31:269–80. doi: 10.1007/s00270-007-9226-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Poon RT, Tso WK, Pang RW, Ng KK, Woo R, Tai KS, et al. A phase I/II trial of chemoembolization for hepatocellular carcinoma using a novel intra-arterial drug-eluting bead. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;5:1100–8. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2007.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Prajapati HJ, Rafi S, El-Rayes BF, Kauh JS, Kooby DA, Kim HS. Safety and feasibility of same-day discharge of patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma treated with doxorubicin drug-eluting bead transcatheter chemoembolization. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2012;23:1286–93.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2012.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dhanasekaran R, Kooby DA, Staley CA, Kauh JS, Khanna V, Kim HS. Comparison of conventional transarterial chemoembolization (TACE) and chemoembolization with doxorubicin drug eluting beads (DEB) for unresectable hepatocelluar carcinoma (HCC) J Surg Oncol. 2010;101:476–80. doi: 10.1002/jso.21522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ferrer Puchol MD, la Parra C, Esteban E, Vaño M, Forment M, Vera A, et al. Comparison of doxorubicin-eluting bead transarterial chemoembolization (DEB-TACE) with conventional transarterial chemoembolization (TACE) for the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma. Radiologia. 2011;53:246–53. doi: 10.1016/j.rx.2010.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Petruzzi NJ, Frangos AJ, Fenkel JM, Herrine SK, Hann HW, Rossi S, et al. Single-center comparison of three chemoembolization regimens for hepatocellular carcinoma. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2013;24:266–73. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2012.10.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Recchia F, Passalacqua G, Filauri P, Doddi M, Boscarato P, Candeloro G, et al. Chemoembolization of unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: Decreased toxicity with slow-release doxorubicineluting beads compared with lipiodol. Oncol Rep. 2012;27:1377–83. doi: 10.3892/or.2012.1651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sacco R, Bargellini I, Bertini M, Bozzi E, Romano A, Petruzzi P, et al. Conventional versus doxorubicin-eluting bead transarterial chemoembolization for hepatocellular carcinoma. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2011;22:1545–52. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2011.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Scartozzi M, Baroni GS, Faloppi L, Paolo MD, Pierantoni C, Candelari R, et al. Trans-arterial chemo-embolization (TACE), with either lipiodol (traditional TACE) or drug-eluting microspheres (precision TACE, pTACE) in the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma: Efficacy and safety results from a large mono-institutional analysis. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2010;29:164. doi: 10.1186/1756-9966-29-164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Song MJ, Chun HJ, Song do S, Kim HY, Yoo SH, Park CH, et al. Comparative study between doxorubicin-eluting beads and conventional transarterial chemoembolization for treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 2012;57:1244–50. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2012.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Song MJ, Park CH, Kim JD, Kim HY, Bae SH, Choi JY, et al. Drug-eluting bead loaded with doxorubicin versus conventional Lipiodol-based transarterial chemoembolization in the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma: A case-control study of Asian patients. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;23:521–7. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0b013e328346d505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.van Malenstein H, Maleux G, Vandecaveye V, Heye S, Laleman W, van Pelt J, et al. A randomized phase II study of drug-eluting beads versus transarterial chemoembolization for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. Onkologie. 2011;34:368–76. doi: 10.1159/000329602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brown DB, Nikolic B, Covey AM, Nutting CW, Saad WE, Salem R, et al. Quality improvement guidelines for transhepatic arterial chemoembolization, embolization, and chemotherapeutic infusion for hepatic malignancy. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2012;23:287–94. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2011.11.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Abdo AA, Hassanain M, AlJumah A, Al Olayan A, Sanai FM, Alsuhaibani HA, et al. Saudi guidelines for the diagnosis and management of hepatocellular carcinoma: Technical review and practice guidelines. Ann Saudi Med. 2012;32:174–99. doi: 10.5144/0256-4947.2012.174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bruix J, Sherman M. Management of hepatocellular carcinoma: An update. Hepatology. 2011;53:1020–2. doi: 10.1002/hep.24199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kalva SP, Iqbal SI, Yeddula K, Blaszkowsky LS, Akbar A, Wicky S, et al. Transarterial chemoembolization with Doxorubicin-eluting microspheres for inoperable hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastrointest Cancer Res. 2011;4:2–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kalayci C, Johnson PJ, Raby N, Metivier EM, Williams R. Intraarterial adriamycin and lipiodol for inoperable hepatocellular carcinoma: A comparison with intravenous adriamycin. J Hepatol. 1990;11:349–53. doi: 10.1016/0168-8278(90)90220-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lencioni R, Malagari K, Vogl T, Pilleul F, Denys A, Watkinson A, et al. A randomised phase II trial of a drug eluting bead in the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma by transcatheter arterial chemoembolization. J Hepatol. 2009;50:S41. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gao S, Yang Z, Zheng Z, Yao J, Deng M, Xie H, et al. Doxorubicin-eluting bead versus conventional TACE for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: A meta-analysis. Hepatogastroenterology. 2013;60:813–20. doi: 10.5754/hge121025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Huang K, Zhou Q, Wang R, Cheng D, Ma Y. Doxorubicin-eluting beads versus conventional transarterial chemoembolization for the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;29:920–5. doi: 10.1111/jgh.12439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wiggermann P, Sieron D, Brosche C, Brauer T, Scheer F, Platzek I, et al. Transarterial Chemoembolization of Child-A hepatocellular carcinoma: Drug-eluting bead TACE (DEB TACE) vs. TACE with cisplatin/lipiodol (cTACE) Med Sci Monit. 2011;17:CR189–95. doi: 10.12659/MSM.881714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Burrel M, Reig M, Forner A, Barrufet M, de Lope CR, Tremosini S, et al. Survival of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma treated by transarterial chemoembolisation (TACE) using Drug Eluting Beads. Implications for clinical practice and trial design. J Hepatol. 2012;56:1330–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2012.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]