Abstract

Background

Point‐of‐care (POC) tests for diagnosing schistosomiasis include tests based on circulating antigen detection and urine reagent strip tests. If they had sufficient diagnostic accuracy they could replace conventional microscopy as they provide a quicker answer and are easier to use.

Objectives

To summarise the diagnostic accuracy of: a) urine reagent strip tests in detecting active Schistosoma haematobium infection, with microscopy as the reference standard; and b) circulating antigen tests for detecting active Schistosoma infection in geographical regions endemic for Schistosoma mansoni or S. haematobium or both, with microscopy as the reference standard.

Search methods

We searched the electronic databases MEDLINE, EMBASE, BIOSIS, MEDION, and Health Technology Assessment (HTA) without language restriction up to 30 June 2014.

Selection criteria

We included studies that used microscopy as the reference standard: for S. haematobium, microscopy of urine prepared by filtration, centrifugation, or sedimentation methods; and for S. mansoni, microscopy of stool by Kato‐Katz thick smear. We included studies on participants residing in endemic areas only.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently extracted data, assessed quality of the data using QUADAS‐2, and performed meta‐analysis where appropriate. Using the variability of test thresholds, we used the hierarchical summary receiver operating characteristic (HSROC) model for all eligible tests (except the circulating cathodic antigen (CCA) POC for S. mansoni, where the bivariate random‐effects model was more appropriate). We investigated heterogeneity, and carried out indirect comparisons where data were sufficient. Results for sensitivity and specificity are presented as percentages with 95% confidence intervals (CI).

Main results

We included 90 studies; 88 from field settings in Africa. The median S. haematobium infection prevalence was 41% (range 1% to 89%) and 36% for S. mansoni (range 8% to 95%). Study design and conduct were poorly reported against current standards.

Tests for S. haematobium

Urine reagent test strips versus microscopy

Compared to microscopy, the detection of microhaematuria on test strips had the highest sensitivity and specificity (sensitivity 75%, 95% CI 71% to 79%; specificity 87%, 95% CI 84% to 90%; 74 studies, 102,447 participants). For proteinuria, sensitivity was 61% and specificity was 82% (82,113 participants); and for leukocyturia, sensitivity was 58% and specificity 61% (1532 participants). However, the difference in overall test accuracy between the urine reagent strips for microhaematuria and proteinuria was not found to be different when we compared separate populations (P = 0.25), or when direct comparisons within the same individuals were performed (paired studies; P = 0.21).

When tests were evaluated against the higher quality reference standard (when multiple samples were analysed), sensitivity was marginally lower for microhaematuria (71% vs 75%) and for proteinuria (49% vs 61%). The specificity of these tests was comparable.

Antigen assay

Compared to microscopy, the CCA test showed considerable heterogeneity; meta‐analytic sensitivity estimate was 39%, 95% CI 6% to 73%; specificity 78%, 95% CI 55% to 100% (four studies, 901 participants).

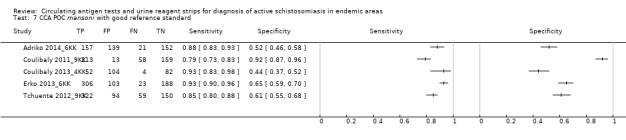

Tests for S. mansoni

Compared to microscopy, the CCA test meta‐analytic estimates for detecting S. mansoni at a single threshold of trace positive were: sensitivity 89% (95% CI 86% to 92%); and specificity 55% (95% CI 46% to 65%; 15 studies, 6091 participants) Against a higher quality reference standard, the sensitivity results were comparable (89% vs 88%) but specificity was higher (66% vs 55%). For the CAA test, sensitivity ranged from 47% to 94%, and specificity from 8% to 100% (four studies, 1583 participants).

Authors' conclusions

Among the evaluated tests for S. haematobium infection, microhaematuria correctly detected the largest proportions of infections and non‐infections identified by microscopy.

The CCA POC test for S. mansoni detects a very large proportion of infections identified by microscopy, but it misclassifies a large proportion of microscopy negatives as positives in endemic areas with a moderate to high prevalence of infection, possibly because the test is potentially more sensitive than microscopy.

23 April 2019

No update planned

Other

Reliable evidence with clear conclusions. All eligible published studies found in the last search (30 Jun, 2014) were included.

Keywords: Adult; Animals; Child; Female; Humans; Male; Reagent Strips; Schistosoma haematobium; Schistosoma haematobium/immunology; Schistosoma mansoni; Schistosoma mansoni/immunology; Antigens, Helminth; Antigens, Helminth/blood; Cross‐Sectional Studies; Hematuria; Hematuria/diagnosis; Microscopy; Prevalence; Proteinuria; Proteinuria/diagnosis; Reference Standards; Schistosomiasis haematobia; Schistosomiasis haematobia/blood; Schistosomiasis haematobia/diagnosis; Schistosomiasis haematobia/immunology; Schistosomiasis haematobia/urine; Schistosomiasis mansoni; Schistosomiasis mansoni/blood; Schistosomiasis mansoni/diagnosis; Schistosomiasis mansoni/immunology; Schistosomiasis mansoni/urine; Sensitivity and Specificity

Plain language summary

How well do point‐of‐care tests detect Schistosoma infections in people living inendemic areas?

Schistosomiasis, also known as bilharzia, is a parasitic disease common in the tropical and subtropics. Point‐of‐care tests and urine reagent strip tests are quicker and easier to use than microscopy. We estimate how well these point‐of‐care tests are able to detect schistosomiasis infections compared with microscopy.

We searched for studies published in any language up to 30 June 2014, and we considered the study’s risk of providing biased results.

What do the results say?

We included 90 studies involving almost 200,000 people, with 88 of these studies carried out in Africa in field settings. Study design and conduct were poorly reported against current expectations. Based on our statistical model, we found:

• Among the urine strips for detecting urinary schistosomiasis, the strips for detecting blood were better than those detecting protein or white cells (sensitivity and specificity for blood 75% and 87%; for protein 61% and 82%; and for white cells 58% and 61%, respectively). • For urinary schistosomiasis, the parasite antigen test performance was worse (sensitivity, 39% and specificity, 78%) than urine strips for detecting blood. • For intestinal schistosomiasis, the parasite antigen urine test, detected many infections identified by microscopy but wrongly labelled many uninfected people as sick (sensitivity, 89% and specificity, 55%).

What are the consequences of using these tests?

If we take 1000 people, of which 410 have urinary schistosomiasis on microscopy testing, then using the strip detecting blood in the urine would misclassify 77 uninfected people as infected, and thus may receive unnecessary treatment; and it would wrongly classify 102 infected people as uninfected, who thus may not receive treatment.

If we take 1000 people, of which 360 have intestinal schistosomiasis on microscopy testing, then the antigen test would misclassify 288 uninfected people as infected. These people may be given unnecessary treatment. This test also would wrongly classify 40 infected people as uninfected who thus may not receive treatment.

Conclusion of review

For urinary schistosomiasis, the urine strip for detecting blood leads to some infected people being missed and some non‐infected people being diagnosed with the condition, but is better than the protein or white cell tests. The parasite antigen test is not accurate.

For intestinal schistosomiasis, the parasite antigen urine test classifies many microscopy negative people as being infected. This finding may be explained by the low sensitivity of microscopy.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings 1. Summary of findings table for tests to detect S. haematobium.

| What is the diagnostic accuracy of circulating antigen tests and biochemical urine reagent strips in detecting S. haematobium infection? | ||||||

| Patients/Population | People residing in areas endemic for S. haematobium infection (74 out of 90 studies) | |||||

| Prior treatment with praziquantel before baseline study | Yes (6 studies), No (11 studies), Unclear (57 studies) | |||||

| Prior testing | None | |||||

| Settings | Field settings (villages and schools) and 1 outpatient clinic in Africa | |||||

| Index tests | Circulating cathodic antigen test (CCA) Circulating anodic antigen test (CAA)a Urine reagent strips to detect microhaematuria, proteinuria, and leukocyturia |

|||||

| Reference standard | Urine microscopy | |||||

| Importance | These tests are being used as replacements for conventional microscopy in disease control programmes for schistosomiasis, as they are rapid, are easier to use and interpret, and may have comparable sensitivity to microscopy. As control programmes gain impetus and infection intensities decrease, higher sensitivities become a prerequisite for future diagnostics | |||||

| Studies | Cross‐sectional (n = 62), cohort (n = 6), and case‐control studies with controls from same population (n = 3) | |||||

| Quality concerns | Poor reporting of participant characteristics, index test and reference standard methods, and intensity of infection were common concerns. The risk of bias assessment for most included studies was largely unclear for the QUADAS domains Patient Selection, Index Tests, and Reference Tests | |||||

| Test types | Number of evaluations | Summary estimates (95% CI) | In 1000 people tested | |||

| Infected cases S. haematobium |

Missed cases (FNs) |

False‐ positives (FPs) |

All positives (TPs + FPs) |

|||

| Biochemical urine reagent strips | ||||||

| For microhaematuria | 74 | Sens = 75% (71% to 79%) Spec = 87% (84% to 90%) |

410 | 102 | 77 | 384 |

| For proteinuria | 46 | Sens = 61% (53% to 68%) Spec = 82% (77% to 88%) |

410 | 160 | 106 | 356 |

| For leukocyturia | 5 | Sens = 58% (44% to 71%) Spec = 61% (34% to 88%) |

410 | 172 | 230 | 468 |

| Circulating cathodic antigen test (CCA) | ||||||

| Urine POC test | 4 | Sens = 39% (6% to 73%) Spec = 78% (55% to 100%) |

410 | 250 | 94 | 254 |

| Comparisons | ||||||

| Comparison | Comparison type | Number of evaluations and differences in overall accuracy | Explanation | |||

| Microhaematuria vs proteinuria | All studies | 74 microhaematuria vs proteinuria, difference in accuracy (P = 0.25) | We found no evidence of a statistically significant difference in overall accuracy when microhaematuria and proteinuria are carried out and compared in different individuals | Proteinuria would be expected to miss 14% more cases than microhaematuria | Proteinuria would be expected to falsely identify 5% more cases than microhaematuria | |

| Paired studies (tests done in the same individuals) |

44 microhaematuria vs proteinuria, differences in accuracy (P = 0.21) | We found no evidence of a statistically significant difference in overall accuracy when microhaematuria and proteinuria are carried out and compared in the same individuals | ||||

a Studies were insufficient to provide summary estimates for the CAA tests.

When the tests were evaluated against the higher‐quality reference standard (ie when multiple samples were analyzed), sensitivity was lower for microhaematuria (71% vs 76%) and proteinuria (49% vs 61%) in comparison with a lower‐quality reference standard. The specificity of these tests was comparable.

In light‐intensity settings, sensitivity was slightly lower for microhaematuria (73% vs 76%) and specificity was slightly higher (88% vs 86%) compared with results of the overall analysis. In contrast, sensitivity (60% vs 61%) and specificity (83% vs 83%) for proteinuria were comparable.

Microhaematuria and proteinuria had higher sensitivity (77% vs 73% and 67% vs 56%) in children than in mixed populations of adults and children. Specificity was higher for microhaematuria (91% vs 82%) but specificity was comparable for proteinuria (81% vs 82%) in children compared with mixed populations of adults and children.

For the effects of risk of bias, sensitivities and specificities of microhaematuria were comparable when limited to studies with low risk of bias for the participant flow domain. Sensitivity of proteinuria was higher when limited to studies with low risk of bias for the participant selection domain (64%) and the participant flow domain (67%). Specificity on the other hand was comparable for these 2 domains.

Abbreviations: TPs (true‐positives), FPs (false‐positives), FNs (false‐negatives).

Summary of findings 2. Summary of findings table for tests to detect S. mansoni.

| What is the diagnostic accuracy of circulating antigen tests for S. mansoni infection? | ||||||

| Patients/Population | People residing in areas endemic for S. mansoni infection (16 out of 90 studies) | |||||

| Prior treatment with praziquantel before baseline study | Yes (1 study), No (5 studies), Unclear (10 studies) | |||||

| Prior testing | None | |||||

| Settings | Field settings (villages, schools, and military camp) in Africa and South America | |||||

| Index tests | Circulating cathodic antigen test (CCA) Circulating anodic antigen test (CAA)a |

|||||

| Reference standard | Stool microscopy | |||||

| Importance | These tests are being used as replacements for conventional microscopy in disease control programmes for schistosomiasis, as they are rapid, are easier to use and interpret, and may have comparable sensitivity to microscopy. As control programmes gain impetus and infection intensities decrease, higher sensitivities become a prerequisite for future diagnostics | |||||

| Studies | Cross‐sectional studies | |||||

| Quality concerns | Poor reporting of participant characteristics, index test and reference standard methods, and intensity of infection were common concerns. The risk of bias assessment for most included studies was largely unclear for the QUADAS domains Patient Selection, Index Tests, and Reference Tests | |||||

| Test types | Number of evaluations | Summary estimates (95% CI) | In 1000 people tested | |||

| Infected cases S. mansoni |

Missed cases (FNs) |

False‐positives (FPs) |

All positives (TPs + FPs) | |||

| Circulating cathodic antigen test (CCA) | ||||||

| Urine POC test | 15 | Sens = 89% (86% to 92%); Spec = 55% (46% to 65%) | 360 | 40 | 288 | 608 |

a Studies were insufficient to provide summary estimates for CAA tests.

When measured against a higher‐quality reference standard, sensitivity of CCA POC for S. mansoni was comparable (88% vs 88%) but specificity was higher (66% vs 55%) than when measured against a lower‐quality reference standard.

At a positivity threshold ≥ 1, sensitivity of CCA POC for S. mansoni was lower (72% vs 87%) and specificity higher (85% vs 61%) than at a positivity threshold of trace‐positive.

Data were insufficient to estimate the sensitivity of CCA POC for S. mansoni in light‐intensity settings.

For the effects of risk of bias, sensitivity and specificity of CCA POC for S. mansoni were comparable when limited to studies with low risk of bias for the participant flow domain.

Abbreviations: TPs (true‐positives), FPs (false‐positives), FNs (false‐negatives).

Background

Target condition being diagnosed

Schistosomiasis, also known as bilharzia, is the second major parasitic disease affecting tropical and subtropical regions after malaria. It is caused by trematode worms of the genus Schistosoma (Gryseels 2012). The latest estimates show that schistosomiasis is endemic in 76 countries, with 779 million people at risk of infection and approximately 207 million people currently infected. Sub‐Saharan Africa accounts for more than 90% of current cases of schistosomiasis (Engels 2002; WHO 2010; Gryseels 2012). The global burden of disease in 2004 was estimated at 13 to 15 million disability‐adjusted life‐years (DALYs) lost as the result of schistosomiasis (King 2010a). These estimates could be an underestimate resulting from the low sensitivity of routinely used diagnostic tests (King 2010a; King 2010b).

Five main schistosome species are known to infect man (Schistosoma mansoni, Schistosoma haematobium,Schistosoma japonicum, Schistosoma intercalatum, and Schistosoma mekongi), of which S. mansoni, S. haematobium, and S. japonicum have the greatest impact on morbidity (Gryseels 2006). The focus of this review will be on diagnosing infection caused by S. mansoni and S. haematobium, as they are more widespread globally and account for most infections and associated morbidity worldwide. These species cause intestinal schistosomiasis and urogenital schistosomiasis, respectively. As outlined in Appendix 1, urogenital schistosomiasis presents with blood in urine (haematuria), proteins in urine (proteinuria), or white blood cells in urine (leukocyturia). In its chronic form, it presents with major bladder, kidney, and genital pathologies including chronic renal failure. Intestinal schistosomiasis presents with abdominal pain and in its chronic and severe forms can present with enlarged liver (hepatomegaly), abdomen distended with fluid (ascites), and liver failure.

Currently, no vaccine is available to protect against schistosomal infection (Rollinson 2009; Bethony 2011). If left untreated, schistosomal infection may result in chronic disease. The current drug of choice is praziquantel, which is cheap (costing less than USD 0.15 per treatment) and safe and causes few side effects. Praziquantel however is ineffective against the eggs and larval forms of schistosome worms (Gryseels 2012; Rollinson 2013). Mass praziquantel treatment of populations at risk of infection is now routine in many endemic areas (WHO 2010; Rollinson 2013). Reinfections rapidly occur as the result of recurrent direct contact with water bodies infected with schistosomal parasites (WHO/TDR 2006; Rollinson 2009; Rollinson 2013). No strong evidence of clinically relevant drug resistance is available (Geerts 2001; Doenhoff 2002; Fenwick 2003; Doenhoff 2009; Greenberg 2013). However reports have described heterogeneities in egg reduction rates and in systematic non‐clearers of infection after treatment with praziquantel (Black 2009; Melman 2009; Ahmed 2012). In the long run, mass treatment has limitations related to cost‐effectiveness (French 2010), poor sustainability (Utzinger 2009), poor drug compliance by individuals (Guo 2005; Croce 2010), and increased drug selection pressure (Greenberg 2013).

Accurate and affordable diagnostic tools are essential for providing targeted treatment and for maximizing the success of control of schistosomiasis in endemic areas; they are required for monitoring drug efficacy as well. Diagnosis of schistosomiasis can be performed directly or indirectly. Direct methods include detection of schistosome eggs in urine or stool by microscopy, detection of schistosome antigens in serum or urine samples, and detection of Schistosoma‐specific DNA in urine, stool, or blood. Indirect methods include questionnaires, biochemical tests (urine reagent strips for microhaematuria/proteinuria/leukocyturia), antibody tests, ultrasonography, computed tomography (CT) scan, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan, endoscopy, and cystoscopy (Feldmeier 1993; Rabello 1997; Doenhoff 2004; Bichler 2006; Gryseels 2012; Cavalcanti 2013).

Currently no gold standard is recommended for the detection of schistosomiasis. Microscopy is the most widely used test for diagnosing schistosomiasis and, although imperfect, it is commonly used as the reference standard in practice. Its sensitivity has been shown to vary with intensity of infection, prevalence of infection, sample preparation techniques, stool consistency, and circadian and day‐to‐day variation of egg counts in stool and/or urine (Doehring 1983; Doehring 1985a; Rabello 1992; Feldmeier 1993; Rabello 1997; van Lieshout 2000; Knopp 2008). This becomes particularly pertinent as control programmes progress and sensitivity of microscopy decreases as the result of reduced infection intensity. Repeated measurements over multiple days from multiple samples and/or multiple smears/slides taken from each sample has been shown to increase sensitivity (Knopp 2008; da Frota 2011; Siqueira 2011; Deelder 2012); however this task increases the time taken to perform the survey and therefore becomes logistically expensive (van Lieshout 2000; Legesse 2007).

Index test(s)

Urine reagent strips and circulating antigen tests are used as alternatives to microscopy for diagnosis of schistosomiasis. Compared with microscopy, urine reagent strips used to detect microhaematuria or proteinuria as a proxy for S. haematobium infection are cheap, quick, and easy to use (Mott 1985; Brooker 2009); have no technical requirements; and are less influenced by the circadian production of schistosome eggs (Murare 1987; Lengeler 1991b). Furthermore, some studies have shown that the sensitivity of these strips is higher than that of urine filtration (French 2007; Robinson 2009), and that a single test with microhaematuria strips is more sensitive than a single test with urine filtration (Taylor 1990)—features that make these strips suitable for screening of urogenital schistosomiasis in the field. However, results should be interpreted against the background of risk for schistosomiasis, as well as any other signs and symptoms that could be indicative of other diseases. Microhaematuria and proteinuria are non‐specific signs that could also result from other ailments such as urogenital infection, malignancy, immune system disorders, metabolic disorders, and trauma.

Circulating antigen tests (circulating anodic antigen (CAA) and circulating cathodic antigen (CCA)) have also been evaluated as replacements for microscopy in the diagnosis of infection due to S. haematobium or S. mansoni. These tests can differentiate between active and past infections, as the circulating antigens are probably present only when there is active infection (Doenhoff 2004). As circulating antigens are released from living worms, antigen levels may correlate directly with parasite load, whilst microscopy does not. This may make the CCA POC test useful in monitoring the dynamics of worm burdens and clearance of worms after treatment (Cavalcanti 2013; Rollinson 2013). However, the sensitivity of these tests has been shown to vary with prevalence of disease and intensity of infection (De Jonge 1988; De Jonge 1989; van Lieshout 1992; De Clerq 1997; Stothard 2006; Ayele 2008; Obeng 2008; Midzi 2009; Colley 2013).

This review evaluates the urine CCA POC test, urine CCA and CAA enzyme‐linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), and serum CCA and CAA ELISA. The urine CCA POC test is a lateral flow assay that uses a nitrocellulose strip with a monoclonal antibody–coated test line to detect the presence of Schistosoma‐specific CCA antigen in urine. When urine from an infected individual flows through the strip, the antigen will bind to the test line, which becomes visible with the binding of added labelled monoclonal antibodies (van Dam 2004). Of note, the urine CCA POC test was developed based on the performance of the ELISA format (Brooker 2009). The urine CCA ELISA was found to have the best diagnostic performance, followed by the serum CAA assay for S. mansoni (Polman 1995; van Lieshout 1995; van Lieshout 2000). Therefore, although they are not rapid tests, the accuracy measures of ELISA tests will be systematically assessed, as the summary measures obtained may guide the ongoing development of improved POC tests.

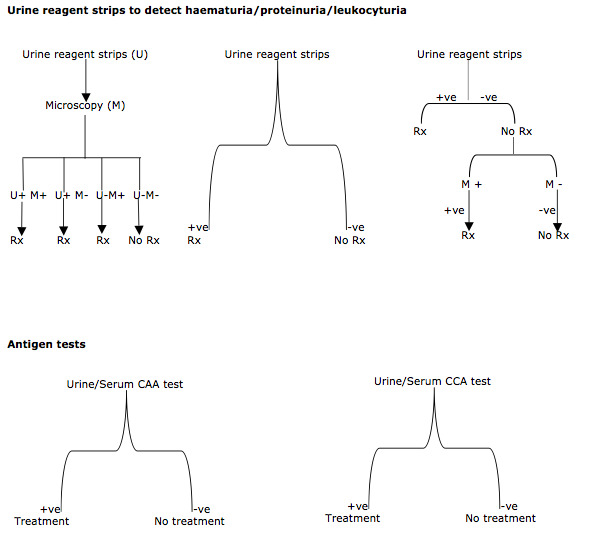

So far, a range of accuracy measures have been reported for urine reagent tests and for circulating antigen tests. Diagnostic and treatment strategies in endemic areas vary with results of these tests (Appendix 2) and depend on financial and human resource capacity.

Clinical pathway

Patients suspected of having active S. haematobium or S. mansoni infection in endemic settings.

Prior test(s)

As outlined in Appendix 2, current practice in endemic settings is to use urine reagent strips as a replacement for microscopy or as a triage test (before microscopy), or circulating antigen tests as a replacement for microscopy. In line with practice in disease control programmes, we focus on the role of these tests as alternatives to microscopy. We will not consider prior testing with other tests, as this is rarely done in public health programmes.

Role of index test(s)

We are interested in the following purposes for testing.

Reagent strips to detect microhaematuria, proteinuria, or leukocyturia as a replacement test for microscopy for S. haematobium infection.

CCA point‐of‐care test as a replacement test for microscopy for S. haematobium or S. mansoni infection.

Alternative test(s)

Apart from the two test types mentioned above, a range of other tests can be used to screen for schistosomiasis. However, all are used in different situations and in different circumstances than the tests mentioned above.

Questionnaires have been used for the initial rapid screening for urinary schistosomiasis in high‐risk communities in endemic areas (Lengeler 1991a; Feldmeier 1993; Chitsulo 1995). These questionnaires rely on self‐reporting of blood in urine. Studies have shown that questionnaires demonstrate moderate to high sensitivities and specificities when used to screen individuals for urogenital schistosomiasis in high‐prevalence areas but low sensitivity and specificity in low‐prevalence areas (Lengeler 1991a; Lengeler 1991b; Brooker 2009). Questionnaires for intestinal schistosomiasis have been shown to be less sensitive and specific than those for urogenital schistosomiasis (WHO/TDR 2006; Brooker 2009). Symptoms of intestinal schistosomiasis are associated with many other diseases, which often overlap in range. As co‐infection is the norm rather than a rare occurrence, the questionnaires are less specific. The accuracy of questionnaires has been shown to be influenced by age and gender. When questionnaires are used repeatedly in the same area, respondents are prone to give biased answers, as they know the consequences of the answers they give. Thus, recall bias may interfere with the accuracy of the test. Consequently, relying on questionnaires may become ineffective, making this screening method unsuitable even for follow‐up of patients after treatment (Ansell 1997; Guyatt 1999; Lengeler 2002). As questionnaires are recommended mainly for initial rapid screening and not for routine screening for schistosomiasis, they will not be evaluated in this review.

Serology tests are alternative tests for the diagnosis of schistosomiasis. These tests detect antibodies against worm antigens, egg antigens (soluble egg antigens (SEAs)), or eosinophil cationic proteins (ECPs) (Reimert 1991; Feldmeier 1993; ITM 2007). Available methods include ELISA, indirect immunofluorescence assay (IFA), and indirect haemagglutination assay (IHA). Antibody tests demonstrate high sensitivity even in areas with light infection and therefore can be used in areas with low endemicity. However these tests fall short in distinguishing current active infection from past infection, have low specificity in endemic areas because of cross‐reactivity with antigens of other helminths, and often show antibody levels that remain elevated after treatment; therefore they yield many false‐positive results (Doenhoff 2004; Cavalcanti 2013). Antibody tests may have a role in checking for maintained exposure to schistosomiasis in areas that are moving towards elimination (Rollinson 2013).

The ECP test is an indirect marker of S. haematobium infection and related morbidity (Reimert 2000; Vennervald 2004). Other test examples include rectal biopsy (ITM 2007), cystoscopy and endoscopy, radiological methods (Bichler 2006), FLOTAC (a novel faecal egg count technique) (Knopp 2009; Glinz 2010), and molecular tests using polymerase chain reaction (PCR) (Ten Hove 2008; Oliveira 2010; Knopp 2011). However these tests may be expensive or may require trained laboratory personnel and an elaborate laboratory infrastructure.

Rationale

For improved mapping to ensure effective selective (or targeted) treatment and for accurate data on treatment success with praziquantel, appropriate diagnostic tests are urgently required. When a test for diagnosing schistosomiasis is considered, a test with high sensitivity is paramount, especially when infection is being monitored within a disease control programme. False‐negative results lead to missed treatment and subsequently to more advanced disease or, if occurring after praziquantel treatment, may lead to overestimated cure rates and potentially undetected cases of praziquantel resistance and the spread of the disease. High specificity is also required, as unnecessary treatment due to false‐positive results could reduce cost‐effectiveness in current control programme strategies through potentially inaccurate classification of prevalence levels or in future targeted treatment control programmes (WHO/TDR 2006). On the other hand, a test for mapping of disease (to get an estimation of disease prevalence in an endemic area) may not need sensitivity and specificity as high as those required for monitoring of disease.

There is currently no recommended gold standard for the detection of active schistosomiasis. However, because microscopy is the most commonly used test in practice and is often used as the reference test in studies, we selected it for use as the reference standard within this review to detect S. haematobium and S. mansoni. The primary concern with microscopy is the possibility of missing infected cases (because of its low and varied sensitivity), especially in areas with low intensity of infection. This means that truly infected cases may be missed and misclassified as non‐infected by microscopy. Therefore when comparing an index test against microscopy, the number of false‐positives (potentially true cases classified as positive by the index test and classified as negative by the reference test) may be high, and the index test may present with low specificity. Increasing the sensitivity of microscopy by taking multiple measurements may reduce the number of true cases wrongly classified as non‐infected by microscopy. An index test compared against a more sensitive reference test (microscopy with multiple measurements) may have higher specificity because the number of false‐positives will be low. Our review will therefore also investigate the effect of the quality of the reference standard on the sensitivity and specificity of the index tests being evaluated.

In this case, a test considered as a replacement for microscopy should have comparable sensitivity or should be less costly, portable, faster, and easier to use or interpret, and it should be less demanding logistically. Point‐of‐care tests based on circulating antigen detection and biochemical urine reagent strips in particular are being included (or developed) in disease control strategies, as they are easy to use and interpret, require minimal laboratory infrastructure, are cost‐effective, reduce patient waiting time and potentially therefore reduce loss to follow‐up, and may have comparable or higher sensitivity to microscopy (Loubiere 2010). The results of this review may guide policy makers on appropriate diagnostic tests to use and may help identify research gaps in diagnostic testing for schistosomiasis in endemic areas.

Objectives

With the goals of making recommendations and informing policy makers on which tests to use and identifying research gaps, these were our primary objectives:

To obtain summary estimates of the diagnostic accuracy of urine reagent strip tests for microhaematuria, proteinuria, and leukocyturia in detecting active S. haematobium infection, with microscopy of urine as the reference standard.

To obtain summary estimates of the diagnostic accuracy of circulating antigen tests—a urine POC circulating cathodic antigen (CCA) test, a urine and serum CCA enzyme‐linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) test, and a urine and serum circulating anodic antigen (CAA) test—for detection of active Schistosoma infection in geographical regions endemic for S. mansoni or S. haematobium or both, with microscopy as the reference standard.

To compare the accuracy of the above index tests.

To investigate potential sources of heterogeneity in the diagnostic accuracy of the tests listed above.

Secondary objectives

To investigate whether age and gender of participants, positivity thresholds, prevalence of infection, intensity of infection, quality of the reference standard, effects of praziquantel treatment, infection stage, mixed infections, and the methodological quality of included studies can explain observed heterogeneity in estimates of test accuracy.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included primary observational studies that compared the results of one or more of the index tests versus the reference standard. These studies could be cross‐sectional in design, cohort studies, or diagnostic case‐control studies with cases and controls sampled from the same patient population.

We included studies that provide participant data. Only studies in which true‐positives (TPs), true‐negatives (TNs), false‐positives (FPs), and false‐negatives (FNs) were reported or could be extracted from the data were included.

We excluded case‐control studies with healthy controls, controls from non‐endemic areas, or controls with alternative diagnoses (patients with diseases similar to schistosomiasis), as specificity may be overestimated (Rutjes 2005). False‐positive test results may occur when an alternative disease produces the same pathophysiological changes as the target condition. We also excluded studies that enrolled only participants with proven schistosomiasis, as sensitivity may be overestimated.

Participants

Participants had to be individuals residing in regions where S. haematobium and S. mansoni infections were endemic. We excluded articles that studied travelers originating from non‐endemic countries, as they were typically screened with other tests such as antibody tests.

Index tests

We included studies that evaluated the following tests.

Urine reagent strip tests

A urine reagent strip test is a biochemical semiquantitative test. It is regarded as an indirect indicator of S. haematobium infection or morbidity, as it detects microhaematuria, proteinuria, or leukocyturia (white blood cells in urine) that can develop as a consequence of schistosomal infection (Doehring 1985b;Doehring 1988). This test is cheap and easy to use for rapid screening of urinary schistosomiasis (Feldmeier 1993; Gryseels 2006; Gryseels 2012).

The results of urine reagent tests used to measure haematuria are scored as 0 (negative), trace‐positive (tr), 1+ (5 to 10 erythrocytes/μL), 2++ (10 to 50 erythrocytes/μL), or 3+++ (50 to 250 erythrocytes/μL). For proteinuria, results are scored as 0 (negative), trace‐positive (tr), 1+ (30 mg protein/dL), 2++ (100 mg protein/dL), or 3+++ (500 mg protein/dL) (Murare 1987).

Antigen tests

Antigen tests are based on detection of schistosome antigens in the serum and urine of individuals (Gryseels 2006; WHO/TDR 2006; Gryseels 2012). The main circulating antigens are adult worm gut–associated circulating antigens, and CAA and CCA are the main focus of research.

The CCA dipstick is scored according to test band reaction intensity as negative (‐), trace‐positive (tr), single‐positive (+), double‐positive (++), and triple‐positive (+++) (Stothard 2006). ELISA results are continuous, and positivity thresholds may vary. To estimate the accuracy of ELISA tests, ELISA must have been evaluated against the reference standard only.

Target conditions

Active infection with S. haematobium.

Active infection with S. mansoni.

Reference standards

S. haematobium

For diagnosis of S. haematobium infection, the reference standard is microscopy of urine for examination of schistosome eggs. To increase sensitivity, urine samples can be concentrated by sedimentation, filtration, or centrifugation techniques (Gryseels 2006), or more samples can be examined (Feldmeier 1993). We therefore included studies that use all of these concentration techniques, and to estimate the effect of the quality of the reference standard, we accepted studies using microscopy on a single urine sample (lower‐quality reference standard) and studies performing microscopy on multiple urine samples (higher‐quality reference standard).

S. mansoni

For diagnosis of S. mansoni infection, microscopic examination of schistosome eggs in stool is the reference standard. Sensitivity is increased by preparing a faecal thick smear using the Kato‐Katz (KK) method (Gryseels 2006) or by examining multiple stool samples (Feldmeier 1993). To estimate the effect of the quality of the reference standard, we accepted studies using microscopy on a single stool sample (lower‐quality reference standard) and studies performing microscopy on multiple stool samples (higher‐quality reference standard).

It is important to note that some regions experience mixed infections of S. haematobium and S. mansoni. In such situations, microscopy of both stool and urine samples must be carried out to confirm infection.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We searched the electronic databases MEDLINE, EMBASE, BIOSIS, MEDION, and HTA (Health Technology Assessment). The MEDLINE search strategy is outlined in Appendix 3. We further translated the MEDLINE search to EMBASE and BIOSIS databases to identify additional records. To avoid missing studies, we did not use a diagnostic search filter. We performed the searches on 12 January 2012 and repeated them on 16 November 2012, 29 August 2013, and 30 June 2014.

Searching other resources

We looked through reference lists of relevant reviews and studies and websites of the World Health Organization (WHO), the Schistosomiasis Control Initiative (SCI), and the Schistosomiasis Consortium for Operational Research and Evaluation (SCORE). When possible, we contacted study authors to request extra information.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two independent review authors first looked through titles and abstracts to identify potentially eligible studies. Full‐text articles of these studies were obtained and assessed for study eligibility by two independent review authors using the predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria. Disagreements were resolved through discussion and by consultation with a third review author when necessary.

Data extraction and management

Two independent review authors extracted data onto a data extraction form.

The following data were extracted.

Study authors, publication year, and journal.

Study design.

Study participants—age, sex.

Prevalence of schistosomiasis.

Treatment status of participants with praziquantel—treatment status before study or post treatment.

Reference standard (microscopy), including number of samples per individual and exact volume of stool/urine examined.

Index tests—urine and serum circulating antigen tests (CCA and CAA) and urine reagent strips.

Urine reagent strips—signs measured (microhaematuria, proteinuria, leukocyturia).

Sample preparation techniques—time of day urine/stool sample was taken, intensity of infection—egg counts in urine and stool by microscopy.

Presence of missing or unavailable test results.

Numbers of TPs, FNs, FPs, and FNs.

Assessment of methodological quality

We used the Quality Assessment of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies (QUADAS‐2) tool to assess risk of bias and concerns for applicability of the included studies (Whiting 2011) (Appendix 4). Disagreements were resolved through consensus or by consultation with a third review author. We extracted data using signalling questions and scored for risk of bias and concerns for applicability under the four main domains: participant selection, index test, reference standard, and participant flow.

Statistical analysis and data synthesis

Comparisons of index test versus the reference standard

We analyzed data for the two target conditions (S. haematobium andS. mansoni) separately. Only one included study (Ashton 2011) evaluated the ability of a test to detect S. haematobium and/orS. mansoni in an area of mixed infection.

Among studies reporting sufficient data for calculating sensitivity and specificity, we plotted their sensitivity and specificity in both forest plots and receiver operating characteristic (ROC) space using the software Review Manager 5.2. We performed a meta‐analysis using the statistical software SAS version 9.2 for test types that had sufficient data points (four or more data points) to be pooled by the statistical models and those that did not demonstrate substantial heterogeneity in ROC space (Macaskill 2010). These tests included the reagent strip for microhaematuria, the reagent strip for proteinuria, the reagent strip for leukocyturia, the CCA POC test for S. haematobium, and the CCA POC test for S. mansoni.

The statistical model selected to perform the overall meta‐analysis depended on the variability of the positivity thresholds, as discussed below. Data for urine reagent strips and urine CCA POC tests were ordinal. These tests are typically scored as 0, trace, 1+, 2+, and 3+, or as 0, 1+, 2+, and 3+.

When data from a test had multiple thresholds, we used the hierarchical summary receiver operating characteristic model (HSROC) to perform the overall meta‐analysis. This model estimates the underlying ROC curve, which describes how sensitivity and specificity of the included studies trade off with each other as thresholds vary. It allows for variation in the parameters of accuracy, thresholds between studies, and the shape of the underlying ROC curve (Rutter 2001; Macaskill 2010). Because this method models sensitivity and specificity indirectly, we calculated average sensitivities and average specificities from the output of the model.

When data from a test had one or a common threshold, we used the bivariate random‐effects model to perform the overall meta‐analysis. This method models sensitivity and specificity directly at a common threshold (Reitsma 2005; Macaskill 2010).

We included all studies in the overall meta‐analysis, whether or not a positivity threshold was included. We assumed that different thresholds were used for the studies that did not report their thresholds, and we used the HSROC model to perform the overall meta‐analysis. For urine reagent strips for microhaematuria and proteinuria, many studies did not report a positivity threshold (n = 41 for microhaematuria and n = 25 for proteinuria). Some studies (n = 2) provided data points at both thresholds of trace and +1. When data points were provided at both thresholds, we selected the data point at threshold trace for the overall analysis; we selected the first stipulated positivity threshold. Leukocyturia had five overall data points, with four data points at threshold trace and one at +1. The CCA POC for S. haematobium had four overall data points, with two at threshold trace and two at +1.

All studies evaluating CCA POC for S. mansoni reported positivity thresholds; five provided data points at both thresholds trace and +1. When data points were provided at both thresholds, we selected the data point at threshold trace for the overall analysis; we selected the first stipulated positivity threshold. The overall analysis therefore contained 15 data points with threshold ≥ trace, for which we used the bivariate model for meta‐analysis.

Comparisons of index tests

We compared the accuracy of the reagent strips for microhaematuria in detecting S. haematobium versus the accuracy of the reagent strips for proteinuria. These were the only tests with sufficient data to enable comparisons between different types of tests. Tests were compared by adding the co‐variate test type to the HSROC model and allowing this to have an effect on the accuracy, threshold, and shape parameters. We performed indirect comparisons and direct comparisons; in the latter, we included only studies that applied both index tests in the same individuals.

Investigations of heterogeneity

We investigated heterogeneity by examining the forest plots and statistically by including co‐variates in the HSROC or bivariate model, by conducting subgroup analysis, and by performing sensitivity analysis. In the HSROC model, we investigated whether these co‐variates affect the parameters of this model—accuracy, threshold, and shape—whereas in the bivariate model, we investigated whether these co‐variates affect sensitivity and specificity.

We did not investigate the effects of infection stage and mixed infection caused by poor reporting and insufficient data for these items.

We investigated the following sources of heterogeneity: quality of the reference standard, positivity threshold, age, gender (proportion of female participation), intensity of infection, prevalence of infection, effect of praziquantel treatment, and QUADAS‐2 risk of bias domains. Of these, the co‐variates gender (proportion of female participation) and prevalence of infection were analyzed as a continuous co‐variate. The rest were analyzed as categorical co‐variates.

We classified studies that used single‐measurement microscopy (one stool and/or one slide or smear) and those that did not report how the reference standard was conducted as using lower‐quality reference standards because single measurements are more likely to miss diseased individuals. We assumed that studies that used multiple measurements of microscopy were likely to report this, given the relevance of this additional effort. Reference standards that used multiple urine or stool samples or multiple slides or smears were classified as higher‐quality reference standards.

For the age co‐variate, many mixed adult/children studies did not state the proportions of adults or children. Some did not state the age of participants. As accuracy data were not provided for age subgroups in most studies, we dichotomized the age co‐variate into the groups 'all ages' and 'children only'. We assumed that studies that did not state the age had included participants of all ages.

Because the proportions of female and male participants were poorly reported at the test level and at the level of the 2 × 2 tables, we analyzed the co‐variate of gender as a continuous variable at the study level. For this co‐variate, gender indicated the proportion of female participation. We focused on females because gender may influence accuracy estimates through factors associated with females, such as menstruation and genitourinary tract infection (Hall 1999; French 2007; Brooker 2009).

The World Health Organization (WHO) recommendations (WHO 2002) categorize intensity of infection for S. haematobium as follows: < 50 eggs/10 mL (light) and ≥ 50 eggs/10 mL (heavy) and intensity of S. mansoni as follows: 1 to 99 eggs per gram (epg) (light), 100 to 399 epg (moderate), and ≥ 400 epg (heavy). In our review, the intensity of infection was reported in different ways (arithmetic mean or range of infection, or geometric mean or range of infection, or proportions of participants with light/moderate/heavy infection) and for most included studies was not reported at all (63% and 65% for microhaematuria and proteinuria, respectively). We used the reported estimates of mean (arithmetic/geometric) or median intensity of infection to classify our studies according to WHO recommendations. We classified as unclear studies that reported only proportions of participants with light/moderate/heavy infections or did not report estimates of intensity of infection.

We examined the effects of treatment with praziquantel on the sensitivity and specificity of the testtype microhaematuria because it was the only test with sufficient data to investigate this. Nine studies provided data on praziquantel treatment; seven were follow‐up studies with praziquantel given at variable intervals (King 1988_a (one year), NGoran 1989 (one month), Kitange 1993 (one year), Lengeler 1993 (one month), Shaw 1998 (six weeks), Magnussen 2001 (one year), French 2007 (one year)), and two indicated that praziquantel had been given before the baseline study was performed (Abdel‐Wahab 1992 (two years), Bogoch 2012 (two years)). When multiple follow‐up studies were performed, we selected data for the first follow‐up evaluation (Shaw 1998; French 2007). However, pooling of results of all studies with varying time intervals would likely introduce a lot of heterogeneity, bias our summary estimates, and lead to overestimates of sensitivity, because studies with long time intervals were likely to have a greater number of participants reinfected compared with studies done at shorter time intervals. We opted to present estimates of sensitivity and specificity of individual studies evaluating the performance of microhaematuria post treatment in the ROC space.

We added the following co‐variates one by one to the HSROC model for microhaematuria and proteinuria and to the bivariate model for CCA POC for S. mansoni: quality of the reference standard, age, gender, and prevalence of infection. We then performed a subgroup analysis for the co‐variates—quality of the reference standard, age, positivity threshold, and intensity of infection—for all three index tests.

Sensitivity analyses

We performed a sensitivity analysis to check the robustness of results when filtration was used as a concentration for urine microscopy for S. haematobium, and to estimate sensitivity and specificity for studies with low risk of bias according to the QUADAS domains, along with participant selection, participant flow, and the reference standard.

Assessment of reporting bias

We did not assess reporting bias. Methods of assessing reporting bias for diagnostic accuracy studies are still being refined. For instance, the Deeks test, a test that has been proposed for use in diagnostic accuracy studies, has low power to detect funnel plot asymmetry, especially when a lot of heterogeneity is present (Macaskill 2010). The studies included in our review showed a lot of heterogeneity; therefore assessments for reporting bias may not yield conclusive results.

Results

Results of the search

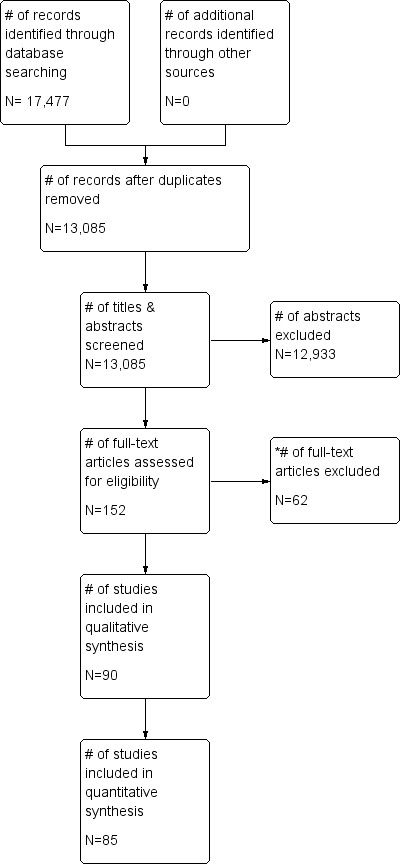

Our search yielded 17,477 hits. After the titles and abstracts were screened, 152 full texts were retrieved, and after full texts were assessed, 90 articles were deemed suitable for inclusion; 62 were excluded. One study author whom we contacted responded to our request for information, but the data submitted did not meet our eligibility criteria. No additional eligible studies were found through additional searches. This review contains results derived from 90 articles. The search results can be seen in Figure 1.

1.

Study flow diagram.

* Reasons for exclusion can be found in the table of Characteristics of excluded studies.

Included studies

Details of included studies can be found in the Characteristics of included studies table. We included 90 studies containing 197,411 participants. Of these included studies, 88 were carried out in Africa, one in South America (Surinam), and one in Asia (Yemen). Only one study was conducted in a hospital setting (antenatal clinic, outpatient setting). The other tests were performed in a field setting (village/school/military camp). S. haematobium was evaluated in most studies (n = 74); 16 evaluated S. mansoni. One study evaluated both species. Eighty studies reported the age of study participants; most of these were conducted in children (n = 50; 62.5%). Median prevalence of S. haematobium infection was 41% (range 1% to 89%), and that of S. mansoni infection was 36% (range 8% to 95%). Median female participation was 50% (Q1 46; Q3 53) for studies that reported gender (n = 46; 51%). Most of the included studies (n = 73; 81%) did not report on the status of praziquantel treatment in the study setting before the baseline study was performed. Eighty‐one studies used a cross‐sectional design; six were cohort studies (longitudinal studies with follow‐up), and three were case‐control studies with controls from the same population (nested case‐control studies). We included 84 English studies and six French studies. One study (Colley 2013), which was retrieved through an updated search, provided recent data for studies retrieved previously (Coulibaly 2011; Shane 2011; Tchuente 2012). In this case, we gathered data for the 2 × 2 tables from the most recent publication (Colley 2013).

Excluded studies

Full details of excluded studies can be found in the Characteristics of excluded studies table. We excluded 62 articles after reading the full texts. We excluded 17 case‐control studies with healthy controls or with controls from non‐endemic areas of schistosomiasis. We could not extract data from 2 × 2 tables for 16 studies. Twelve studies were not test accuracy studies, and four studies enrolled only patients proven to have schistosomiasis. Six studies used reference standards other than microscopy, four studies used other index tests to diagnose schistosomiasis that did not fulfil our inclusion criteria, and three studies performed similar tests on the same population as those reported by other already included studies.

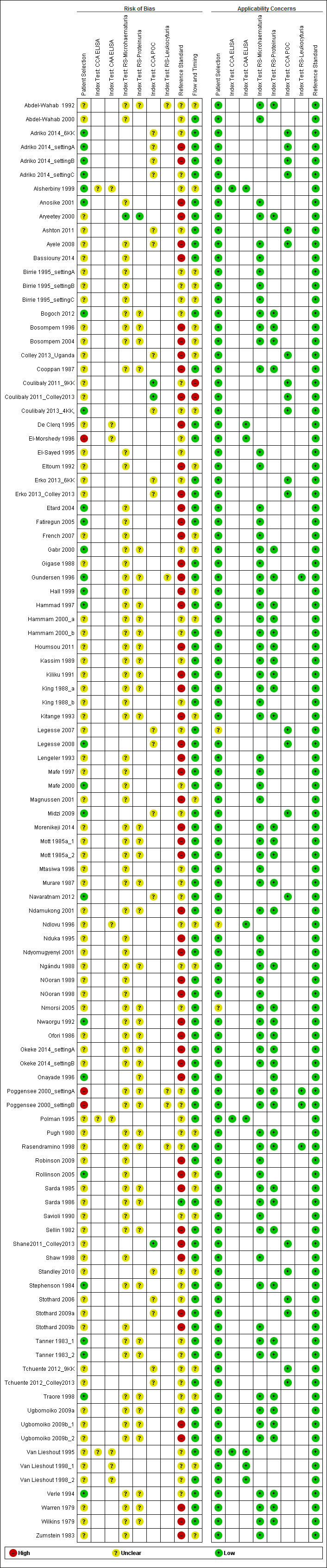

Methodological quality of included studies

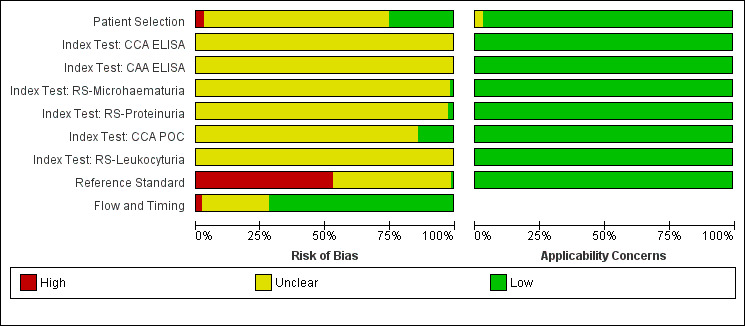

Figure 2 and Appendix 5 show results of the quality appraisal of the 60 included studies. Using the QUADAS‐2 tool, we evaluated these studies for risk of bias in the following domains: participant selection, index test, reference standard, and participant flow. In general, poor reporting of quality items hindered our evaluation of quality. We therefore rated the risk of bias for these domains largely as unclear. In the participant selection domain, about 75% of studies were rated as having unclear risk of bias. For index tests, unclear risk of bias ranged from 80% to about 98% (about 98% for reagent strips for microhaematuria, about 95% for reagent strips for proteinuria, and about 80% for CCA POC testing). None of the studies had high risk of bias in the index test domain. For the reference standard, about 50% of the studies had high risk of bias, whereas the other half had unclear risk of bias. For the participant flow domain, about 75% of the studies had low risk of bias, and the remaining studies had unclear risk. Concerns for applicability for all four domains were predominantly low.

2.

Risk of bias and applicability concerns graph: review authors' judgements about each domain presented as percentages across included studies.

Findings

A summary of the main findings can be found in Table 1 and Table 2. Below we present in detail the overall findings for each index test.

Urine reagent strips

For microhaematuria

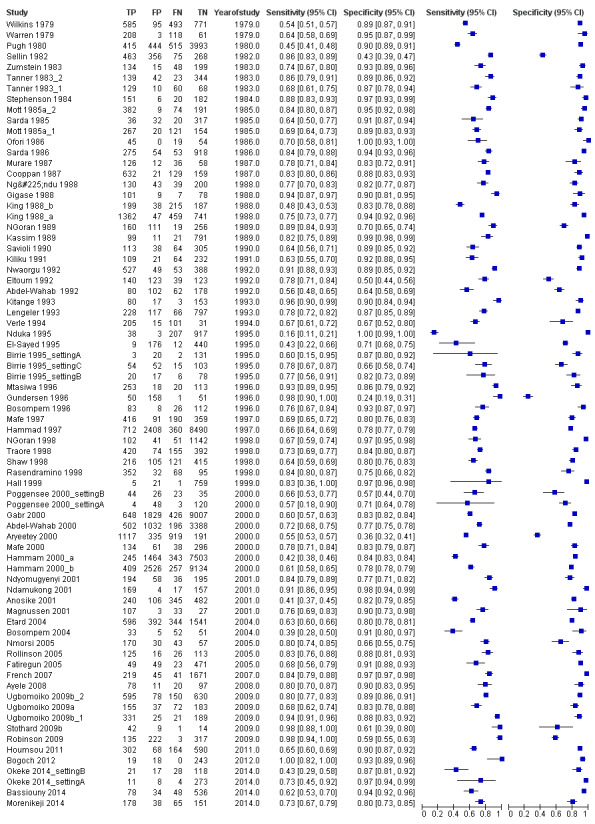

A total of 74 evaluations of the reagent strip for microhaematuria were performed with a total of 102,447 individuals. All evaluations were conducted in Africa. Median prevalence of S. haematobium was 42% (range 1% to 87%), and median female participation was 49% (Q1 49; Q3 53). Most of these evaluations were conducted with a lower‐quality reference standard of only one slide/person (n = 63; 85%), and most evaluations were carried out in mixed populations of adults and children (n = 40; 54%). These evaluations were described in articles published between the years 1979 and 2014; a large proportion (n = 43; 58%) were published between 1979 and 1999. Over these four decades, no clear pattern was evident for effects of year of study on sensitivity and specificity of microhaematuria (see forest plot in Appendix 6). However, the forest plot shows greater heterogeneity for sensitivity compared with specificity.

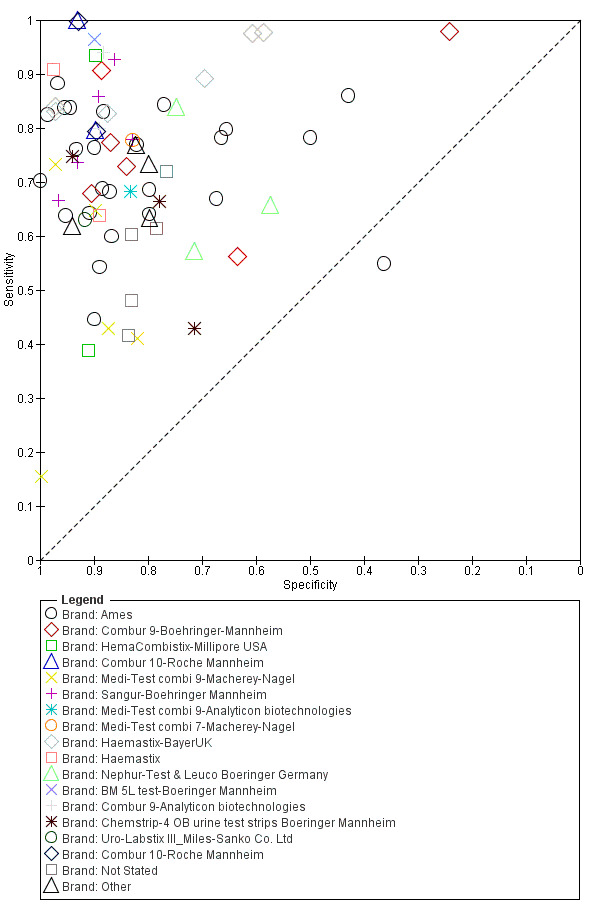

A large range of test brands were used to estimate the sensitivity and specificity of microhaematuria, as shown in Appendix 7. Most evaluations (n = 25; 34%) were performed with the brand from the manufacturer Ames.

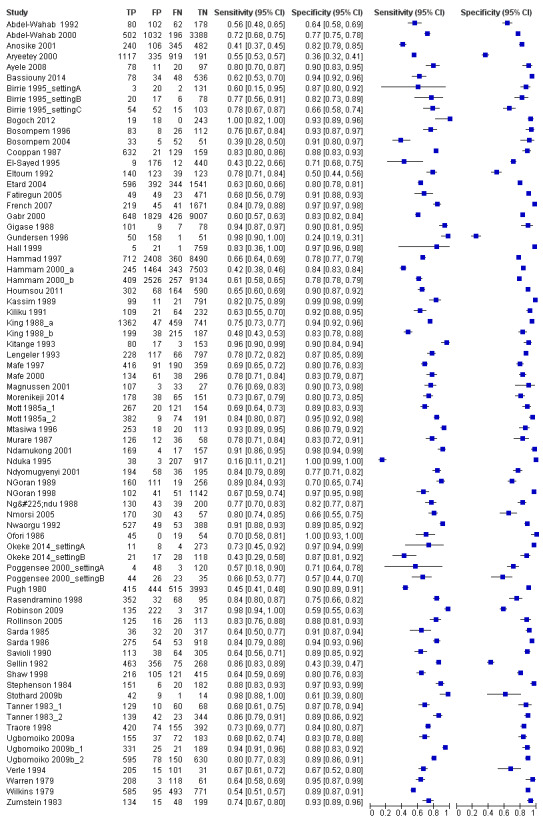

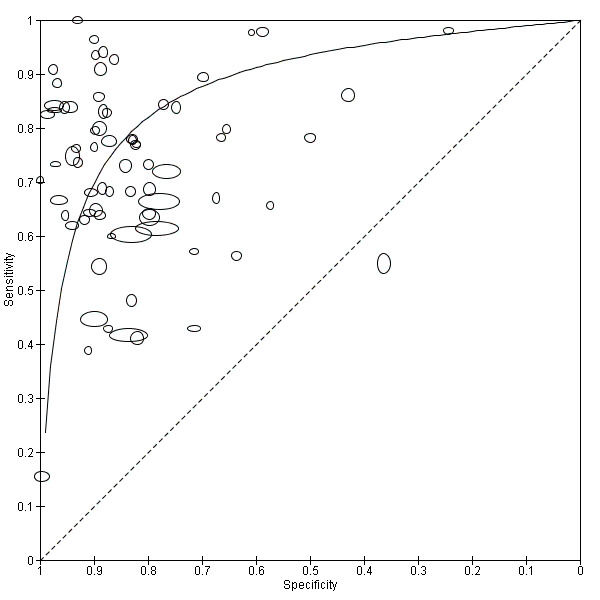

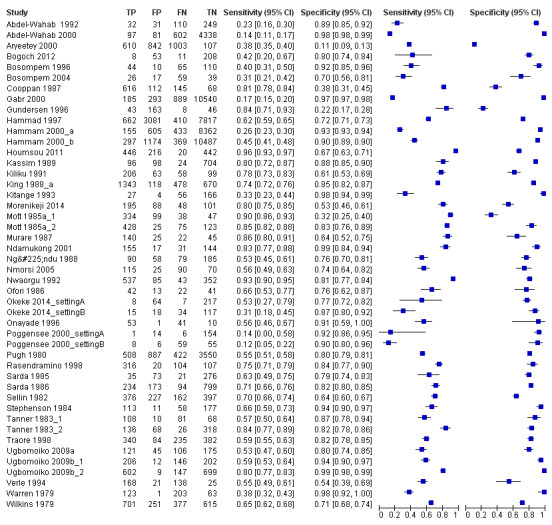

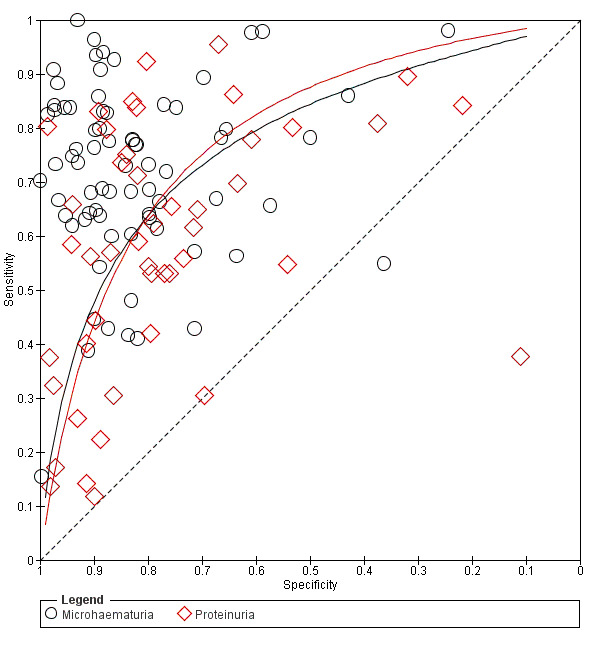

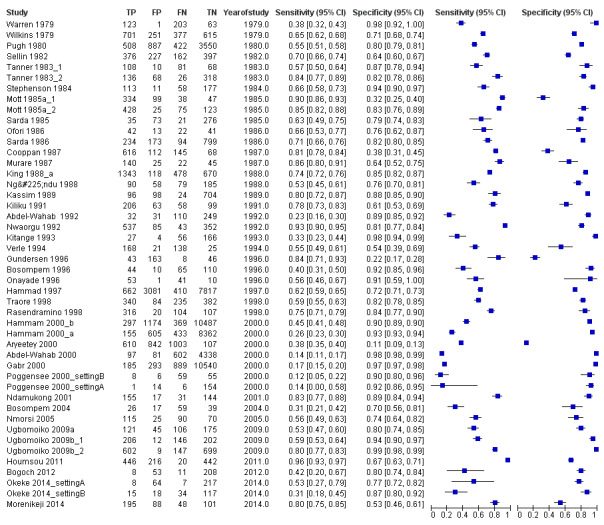

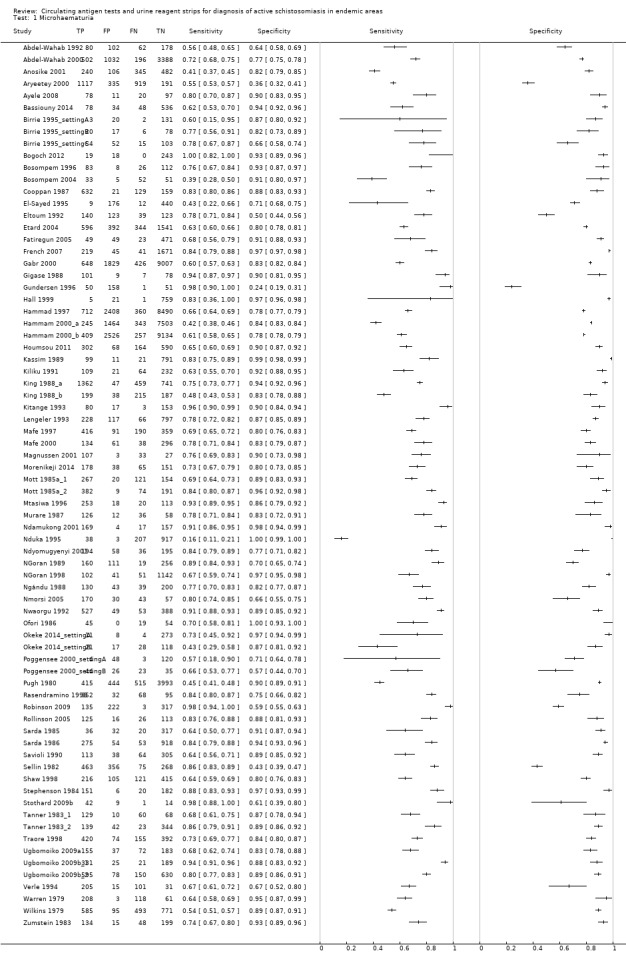

The forest plot (Figure 3) and the HSROC curve (Figure 4) for the reagent strip for microhaematuria reveal heterogeneity for estimates of both sensitivity and specificity.

3.

Forest plot of sensitivity and specificity of the urine reagent strip for microhaematuria.

Squares represent sensitivity and specificity of one study, the black line its confidence interval.

4.

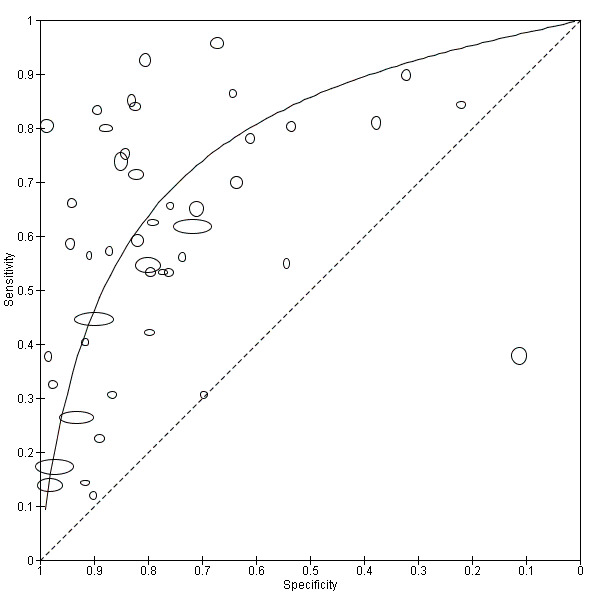

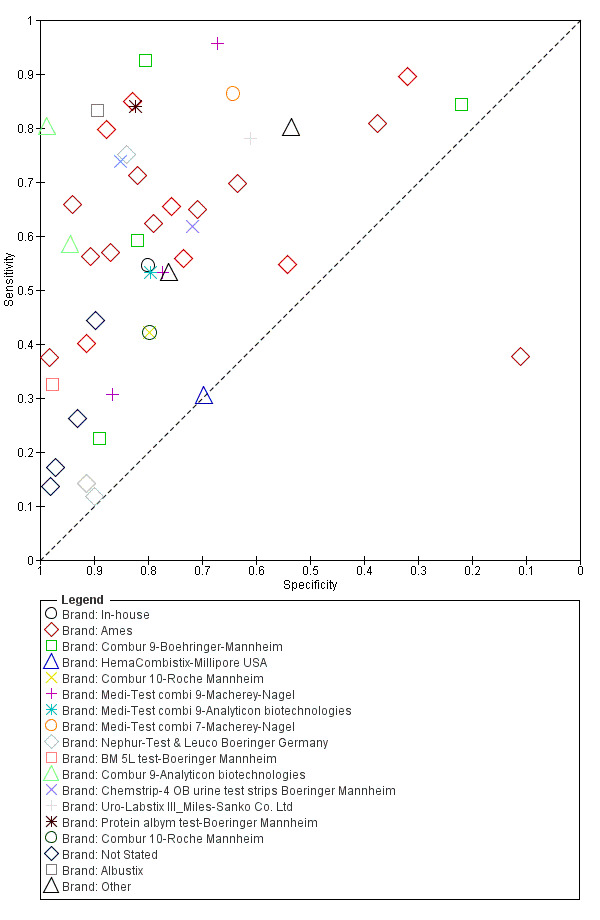

Summary ROC plot of sensitivity versus specificity of the urine reagent strip for microhaematuria.

The size of the points is proportional to the study sample size. The solid line shows the summary ROC curve.

Meta‐analytical sensitivity and specificity (95% confidence interval (CI)) of data at mixed thresholds were 75% (71% to 79%) and 87% (84% to 90%).

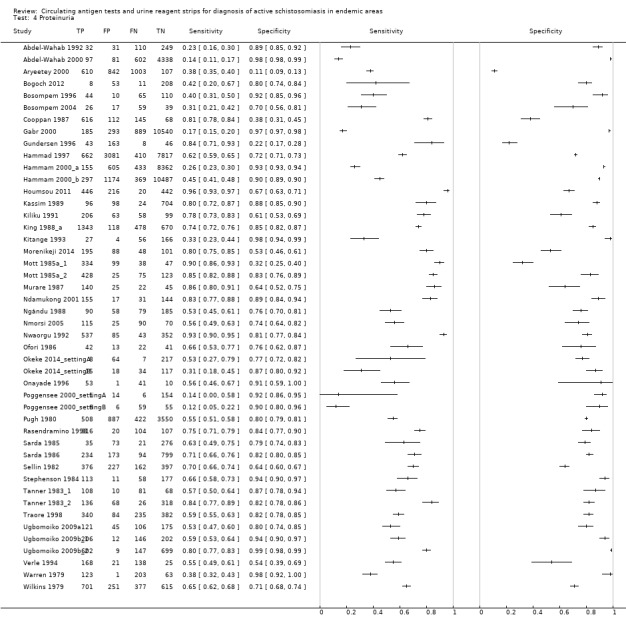

For proteinuria

A total of 46 evaluations of the reagent strip for proteinuria were performed with a total of 82,113 individuals. All evaluations were conducted in Africa. Median prevalence of S. haematobium was 51% (range 4% to 89%), and median female participation was 50% (Q1 46; Q3 53). Most of these evaluations were conducted with a lower‐quality reference standard (n = 36; 78%), and most were carried out in mixed populations of adults and children (n = 28; 61%). These evaluations were described in articles published between the years 1979 and 2014; the largest proportion (n = 27; 59%) were published before the year 2000. Over these four decades, no clear pattern was evident for effects of year of study on sensitivity and specificity of proteinuria (see forest plot in Appendix 8).

A large range of test brands were used to estimate the sensitivity and specificity of proteinuria, as shown in Appendix 9. Most evaluations (n = 17; 37%) were performed using the brand from the manufacturer Ames.

The forest plot (Figure 5) and the HSROC plot (Figure 6) for the reagent strip for proteinuria reveal greater heterogeneity for estimates of sensitivity than specificity. Meta‐analytical sensitivity and specificity (95% CI) of data at mixed thresholds were 61% (53% to 68%) and 82% (77% to 88%).

5.

Forest plot of sensitivity and specificity of the urine reagent strip for proteinuria.

Squares represent the sensitivity and specificity of one study, the black line its confidence interval.

6.

Summary ROC plot of sensitivity versus specificity of the urine reagent strip for proteinuria.

The size of the points is proportional to the study sample size. The solid line shows the summary ROC curve.

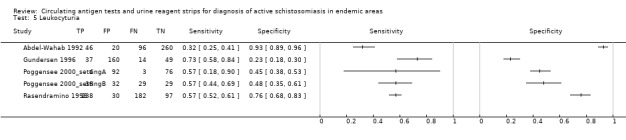

For leukocyturia

A total of five evaluations of the reagent strip for leukocyturia were performed with data from four publications and a total of 1532 individuals. Of these evaluations, two were carried out with a higher‐quality reference standard (40%). Median prevalence of S. haematobium was 34% (range 4% to 77%), and median female participation was 100% (Q1 68; Q3 100). All evaluations except one were conducted in Africa in mixed populations of adults and children. These evaluations were described in articles published between the years 1992 and 2000; most (n = 3) were published before the year 2000. Two different test brands were evaluated. Most evaluations (n = 3; 60%) were done using the Nephur‐test from Boehringer Mannheim.

The forest plot (Figure 7) and the HSROC plot (Figure 8) for the reagent strip for leukocyturia reveal greater heterogeneity for estimates of specificity than sensitivity. The ROC plot also reveals poor accuracy of the test, as most study points lie close to the diagonal line. Meta‐analytical sensitivity and specificity (95% CI) of data at mixed thresholds were 58% (44% to 71%) and 61% (34% to 88%).

7.

Forest plot of sensitivity and specificity of the urine reagent strip for leukocyturia.

Squares represent the sensitivity and specificity of one study, the black line its confidence interval.

8.

Summary ROC plot of sensitivity versus specificity of the urine reagent strip for leukocyturia.

The size of the points is proportional to the study sample size. The solid line shows the summary ROC curve.

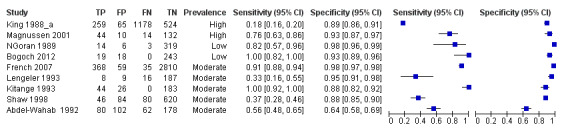

Urine CCA POC test

For S. haematobium

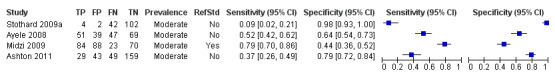

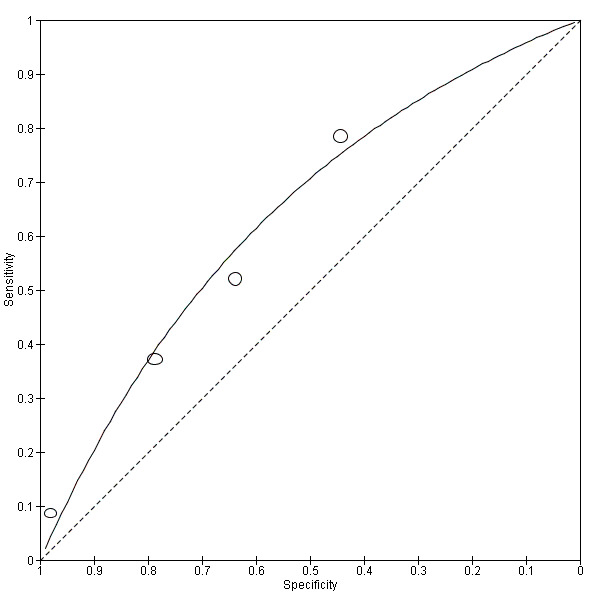

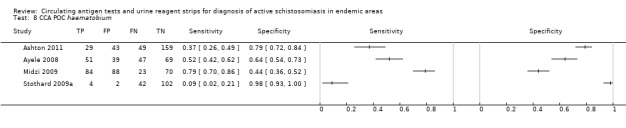

A total of four evaluations of the CCA POC test for S. haematobium were performed on data derived from four publications with a total population of 901 individuals. Median prevalence of S. haematobium was 40% (range 31% to 48%), and median female participation was 47% (Q1 40; Q3 51). Most of these evaluations were conducted with a lower‐quality reference standard (n = 3; 75%). All evaluations were conducted in Africa. All evaluations included data from children only. These evaluations were described in articles published between the years 2008 and 2011. Four different test brands were evaluated.

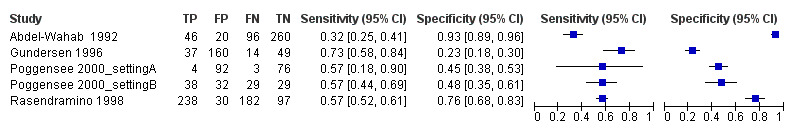

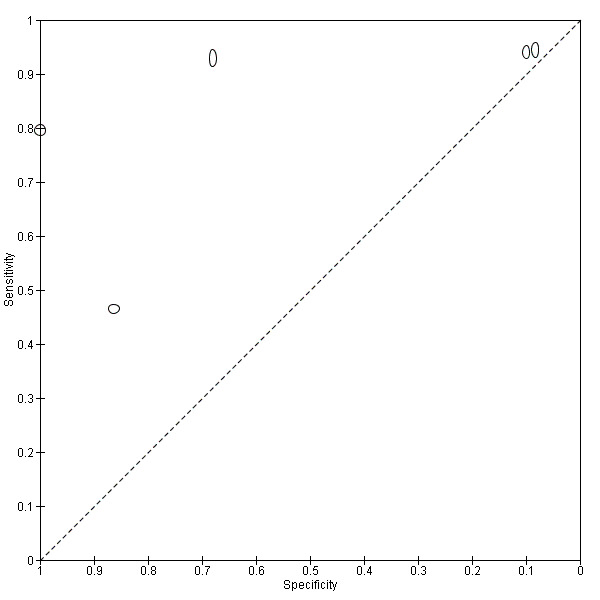

Forest plots (Figure 9) and ROC plots (Figure 10) for this test reveal a high degree of heterogeneity for estimates of both sensitivity and specificity. The ROC plot also reveals poor accuracy of the test, as the study points lie close to the diagonal line. Meta‐analytical sensitivity and specificity (95% CI) of data at mixed thresholds were 39% (6% to 73%) and 78% (55% to 100%).

9.

Forest plot of the sensitivity and specificity of the urine CCA POC test for S. haematobium.

Squares represent the sensitivity and specificity of one study, the black line its confidence interval.

10.

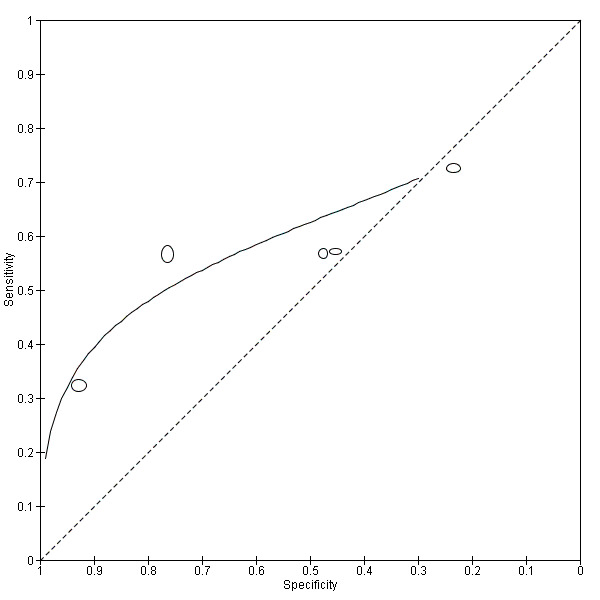

Summary ROC plot of sensitivity versus specificity of the urine CCA POC test for S. haematobium.

The size of the points is proportional to the study sample size. The solid line shows the summary ROC curve.

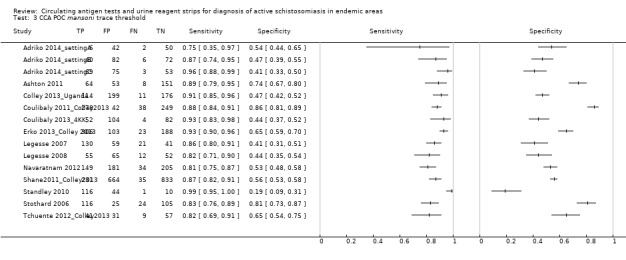

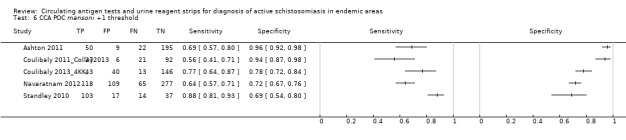

For S. mansoni

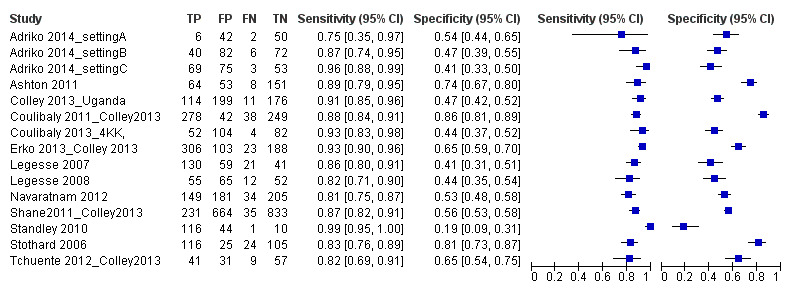

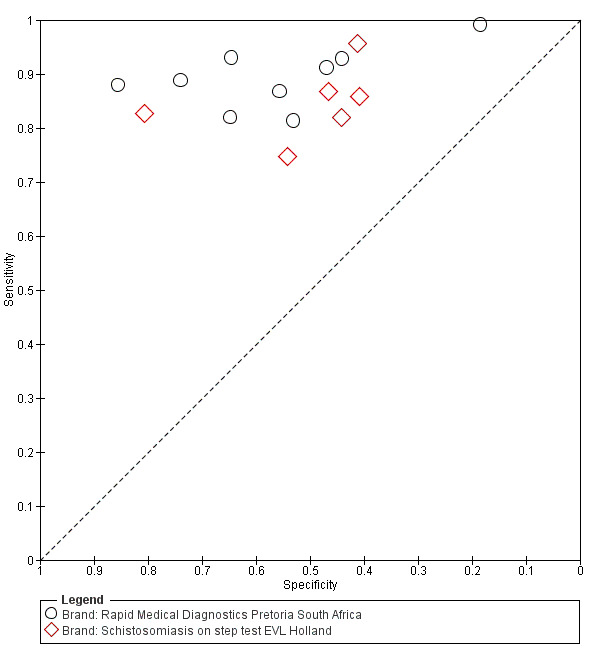

A total of 15 evaluations of the CCA POC test for S. mansoni were performed on data derived from 13 publications with a total population of 6091 individuals. Median prevalence of S. mansoni was 36% (range 8% to 68%), and median female participation was 49% (Q1 48; Q3 51). Most of these evaluations were conducted with a lower‐quality reference standard (n = 10; 67%). All evaluations were conducted in Africa, and all except one included data from children only. These 15 evaluations were described in articles published between the years 2007 and 2014. Two different test brands were evaluated: Rapid Diagnostic Tests from Pretoria South Africa and Schistosomiasis One Step Test from EVL Holland, as shown in Appendix 10. Most evaluations (n = 9) were performed using the Rapid Diagnostic Tests from South Africa.

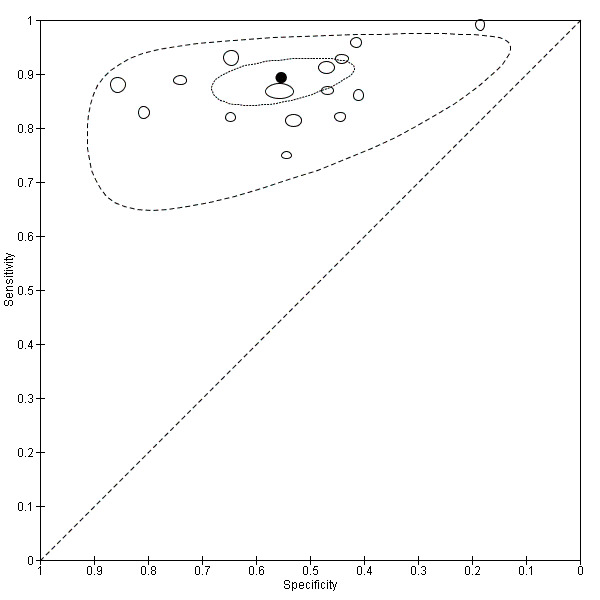

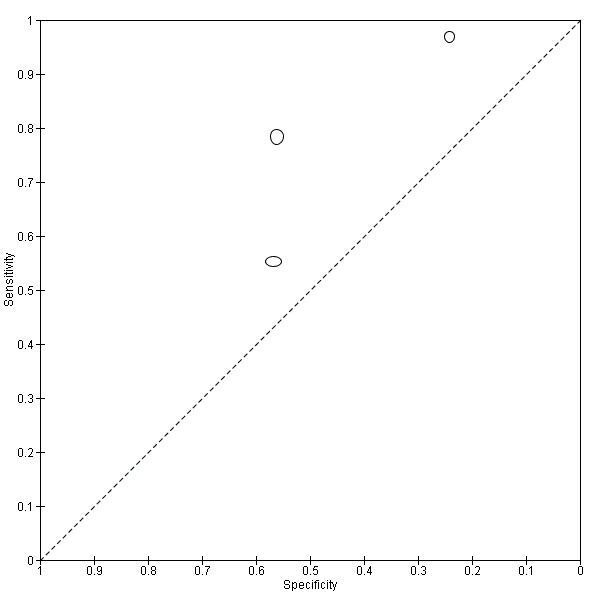

The forest plot for this test reveals greater heterogeneity for estimates of specificity versus estimates of sensitivity (Figure 11). Meta‐analytical sensitivity and specificity (95% CI) of data at a threshold ≥ trace positive were 89% (86% to 92%) and 55% (46% to 65%) (Figure 12).

11.

Forest plot of sensitivity and specificity of the urine CCA POC test for S. mansoni.

Squares represent the sensitivity and specificity of one study, the black line its confidence interval. Colley 2013 was a study that included data for 5 studies (done in different countries). Some of the studies had been published earlier (Coulibaly 2011, Erko 2013, Shane 2011, Tchuente 2012). In this case, we used data from Colley 2013, which provided the most recent and updated data.

12.

Summary ROC plot of sensitivity versus specificity of the urine CCA POC test for S. mansoni.

The size of the points is proportional to the study sample size. The thick black point shows the average value for sensitivity and specificity. The inner ellipse around the black spot represents the 95% confidence regions around the summary estimates. The outer ellipse represents the prediction region.

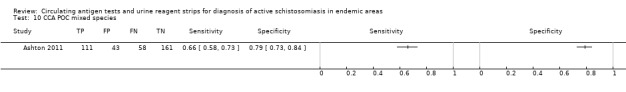

For mixed infection

One study assessed the capability of the POC test to detect schistosomiasis in an area of mixed S. haematobium and S. mansoni infection. This evaluation was conducted in Africa (Southern Sudan) in children only and was published in 2011. The brand used was Rapid Diagnostic Tests from Pretoria, South Africa. The sensitivity of the test was 66%, and the specificity was 79%. No meta‐analysis was performed for this test because of insufficient data.

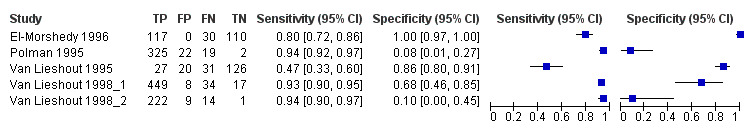

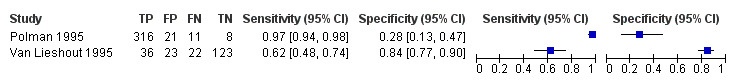

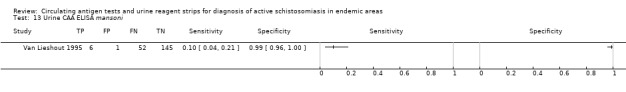

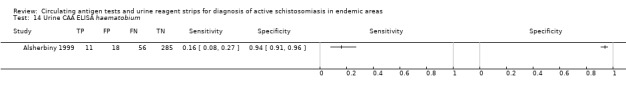

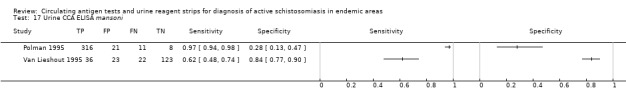

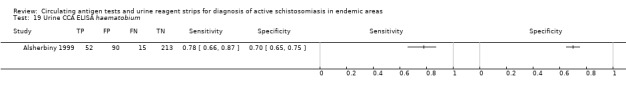

CAA ELISA test

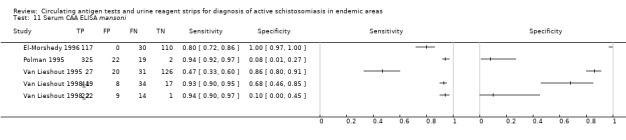

Serum

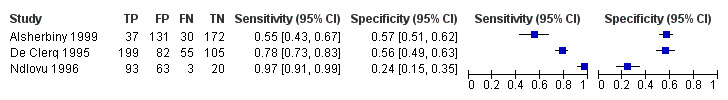

A total of five evaluations of the serum CAA test for S. mansoni were performed on data derived from four publications (total population 1583, years of publication 1995 to 1998). Median prevalence of S. mansoni was 93% (range 28% to 96%), and median female participation was 49% (Q1 49; Q3 51). All of these evaluations were conducted using relatively higher‐quality reference standards (n = 5; 100%). All were in‐house assays, and one study involved only children. Sensitivity of the serum CAA ELISA for S. mansoni ranged from 47% to 94%, and specificity ranged from 8% to 100% (Appendix 11). The ROC plot (Appendix 12) reveals a lot of scatter of the estimates of sensitivity and specificity provided by the included studies.

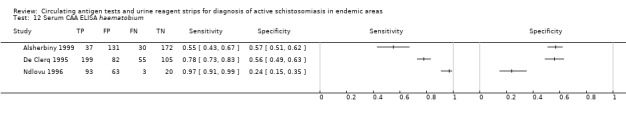

A total of three evaluations of the serum CAA test forS. haematobium were performed on data derived from three publications (total population 990, years of publication 1995 to 1999). Median prevalence of S. haematobium was 38% (range 18% to 57%). Only one study provided data on gender proportions (female participation was 54%). Two of the three evaluations were conducted using a higher‐quality reference standard (67%). All were in‐house assays, and all were carried out in mixed populations of adults and children. Sensitivity of the serum CAA test for S. haematobium ranged from 55% to 97%, and specificity ranged from 24% to 57% (Appendix 13; Appendix 14).

Urine

Only one evaluation of the urine CAA test for S. mansoni was performed on data derived from one publication (total population 204, year of publication 1995).. This was an in‐house assay and was done on data obtained from a mixed population of adults and children. Sensitivity of this test was 10%, and specificity was 99%.

Only one evaluation of the urine CAA test for S. haematobium was performed on data derived from one publication (total population 370, year of publication 1999). This in‐house assay was performed on data obtained from a mixed population of adults and children. Sensitivity of this test was 16%, and specificity was 94%.

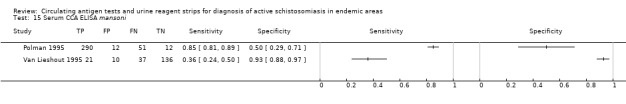

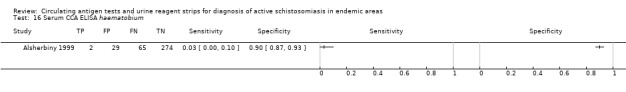

CCA ELISA test

Serum

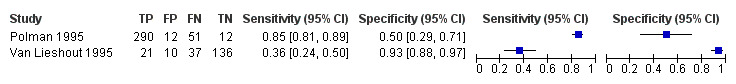

Two evaluations of the urine CCA test for S. mansoni were performed on data derived from two publications (total population 569, year of publication 1995). Both were in‐house assays performed on data obtained from a mixed population of adults and children. Sensitivity of this test ranged from 36% to 85%, and specificity was 50% to 93% (Appendix 15).

Only one evaluation of the urine CCA test for S. haematobium was performed on data derived from one publication (total population 370, year of publication 1999). This in‐house assay was performed on data obtained from a mixed population of adults and children. Sensitivity of this test was 3%, and specificity was 90%.

Urine

Two evaluations of the urine CCA test for S. mansoni were performed on data derived from two publications (total population 560, year of publication 1995). Both were in‐house assays, and neither involved children only. Sensitivity of this test ranged from 62% to 97%, and specificity from 27% to 84% (Appendix 16).

Only one evaluation of the urine CCA test for S. haematobium was performed on data derived from one publication (total population 370, year of publication 1999). This in‐house assay did not involve children only. Sensitivity of this test was 78%, and specificity was 70%.

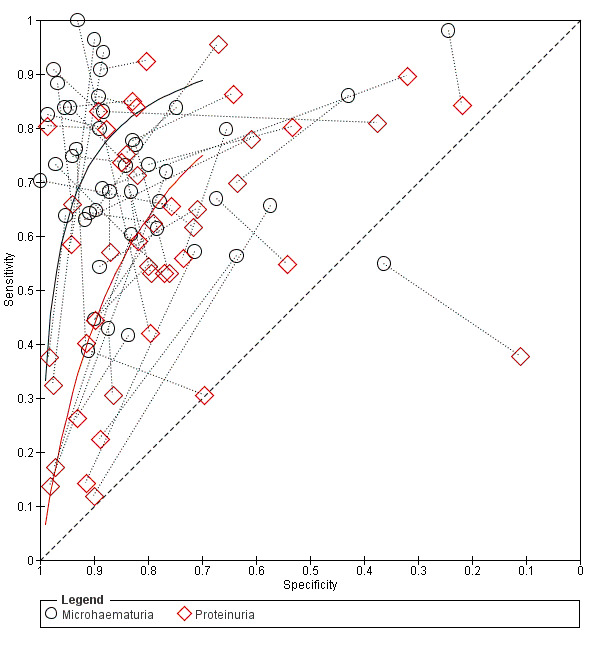

Comparisons of accuracy between reagent strips for microhaematuria and proteinuria

Results of comparisons between microhaematuria and proteinuria are outlined in the Table 1. We first compared accuracy in all studies (indirect comparisons); we then limited the comparison to paired studies (direct comparisons). No statistically significant difference between the accuracy of microhaematuria and that of proteinuria was observed when the tests were compared in different populations using all studies (P = 0.25) (Figure 13). This can be demonstrated in the ROC curve showing the curves of tests as close together and crossing. The difference in accuracy also was not statistically significant when the tests were directly compared in the same individuals (P = 0.21) (Figure 14). A statistically significant difference in the threshold parameter was noted when the tests were compared in different populations using all studies (P < 0.0001), and when the tests were directly compared in the same individuals (P = 0.0009). This could imply that one test has a different operating threshold when compared with the other, and although overall accuracy is not statistically significantly different, sensitivity and specificity may be different under field circumstances.

13.

Summary ROC plot of sensitivity versus specificity showing the indirect comparison between microhaematuria and proteinuria (all studies). The solid lines show the summary ROC curves.

14.

Summary ROC plot of sensitivity and specificity showing the direct comparison between microhaematuria and proteinuria (paired studies). Study points of microhaematuria and proteinuria from the same study are joined by a dotted line. The solid lines show the summary ROC curves.

Investigations of heterogeneity

Co‐variates in the models

The co‐variates quality of reference standard, age, gender (% female participation), prevalence of infection, and intensity of infection were added to the HSROC model. We investigated whether these co‐variates affect the parameters of the HSROC model, that is, accuracy, threshold, and shape.

For the reagent strip for microhaematuria, the co‐variates age (P = 0.002) and gender (% female participation) (P = 0.02) had statistically significant effects only on the threshold parameter of the HSROC model.

For the reagent strip for proteinuria, the co‐variates quality of reference standard (P = 0.01) and prevalence of infection (P value 0.007) had statistically significant effects on the accuracy parameter. Accuracy was higher with the higher‐quality reference standard and in settings with higher prevalence. Other co‐variates did not have a statistically significant effect on any of the other parameters of the HSROC model.

For CCA POC used to detect S. mansoni, no co‐variate had a statistically significant effect on sensitivity or on specificity.

Subgroup analysis

Table 3, Table 4, and Table 5 outline the results of subgroup analyses on the tests microhaematuria, proteinuria, and CCA POC for S. mansoni. When these tests were evaluated against the higher‐quality reference standard (ie when multiple samples were analyzed), sensitivity was lower for microhaematuria (71% vs 76%) and proteinuria (49% vs 68%) than with a lower‐quality reference standard. Specificity of these tests was lower for microhaematuria (85% vs 87%) but higher for proteinuria (83% vs 78%). In contrast, sensitivity was similar (88%) and specificity was higher for the CCA POC test for S. mansoni (66% vs 55%) when measured against a higher‐quality reference standard in comparison with a lower‐quality reference standard.

1. Sources of heterogeneity for urine reagent strip for microhaematuria.

| Group | Co‐variate | Subgroup | n (N = 74) | Sensitivity (95% CI) | Specificity (95% CI) |

| Overall | 0.75 (0.71‐0.79) | 0.87 (0.84‐0.90) | |||

| Subgroup analysis | Reference standard | Higher quality (> 1 sample) | 10 | 0.71 (0.62‐0.80) | 0.85 (0.78‐0.93) |

| Lower quality (1 sample) | 64 | 0.76 (0.71‐0.80) | 0.87 (0.84‐0.90) | ||

| Threshold | ≥ +1 | 23 | 0.80 (0.73‐0.85) | 0.85 (0.78‐0.92) | |

| Age | Children | 34 | 0.77 (0.71‐0.82) | 0.91 (0.87‐0.93) | |

| Intensity of infection | Light | 28 | 0.73 (0.66‐0.79) | 0.88 (0.84‐0.92) | |

| Sensitivity analysis | Concentration | Filtration only | 62 | 0.73 (0.69‐0.78) | 0.86 (0.82‐0.89) |

| QUADAS Patient Selection | Low risk of bias | 16 | 0.77 (0.70‐0.86) | 0.86 (0.79‐0.92) | |

| QUADAS Reference Standard | Low risk of biasa | 1 | ‐ | ‐ | |

| QUADAS Flow and Timing | Low risk of bias | 43 | 0.77 (0.72‐0.82) | 0.87 (0.83‐0.90) |

aInsufficient data for synthesis.

2. Sources of heterogeneity for urine reagent strip for proteinuria.

| Group | Co‐variate | Subgroup | n (N = 46) | Sensitivity (95% CI) | Specificity (95% CI) |

| Overall | 0.61 (0.53‐0.68) | 0.82 (0.77‐0.88) | |||

| Subgroup analysis | Reference standard | Higher quality (> 1 sample) | 9 | 0.49 (0.28‐0.70) | 0.83 (0.76‐0.90) |

| Lower quality (1 sample) | 37 | 0.68 (0.60‐0.76) | 0.78 (0.69‐0.87) | ||

| Threshold | ≥ +1 | 13 | 0.69 (0.56‐0.81) | 0.72 (0.54‐0.90) | |

| Age | Children | 18 | 0.67 (0.56‐0.76) | 0.81 (0.74‐0.87) | |

| Intensity of infection | Light | 15 | 0.60 (0.43‐0.77) | 0.83 (0.73‐0.93) | |

| Sensitivity analysis | Concentration | Filtration only | 35 | 0.62 (0.52‐0.71) | 0.80 (0.73‐0.86) |

| QUADAS Patient Selection | Low risk of bias | 11 | 0.64 (0.50‐0.79) | 0.81 (0.70‐0.93) | |

| QUADAS Reference Standard | Low risk of biasa | 1 | ‐ | ||

| QUADAS Flow and Timing | Low risk of bias | 36 | 0.67 (0.59‐0.76) | 0.82 (0.73‐0.88) |

aInsufficient data for synthesis.

3. Sources of heterogeneity for CCA POC test for S. mansoni.

| Group | Co‐variate | Subgroup | n (N = 15) | Sensitivity (95% CI) | Specificity (95% CI) |

| Overall | 0.89 (0.86‐0.92) | 0.55 (0.46‐0.65) | |||

| Subgroup analysis | Reference standarda | ||||

| Higher quality (> 1 sample) | 5 | 0.88 (0.82‐0.92) | 0.66 (0.46‐0.82) | ||

| Lower quality (1 sample) | 13 | 0.88 (0.85‐0.91) | 0.55 (0.45‐0.66) | ||

| Positivity thresholdb | > +1 | 5 | 0.72 (0.60‐0.82) | 0.85 (0.71‐0.93) | |

| Age | Children | 14 | 0.90 (0.86‐0.92) | 0.56 (0.46‐0.66) | |

| Intensity of infection | Lightc | 3 | ‐ | ‐ | |

| Sensitivity analysis | QUADAS Patient Selection | Low risk of biasc | 3 | ‐ | ‐ |

| QUADAS Reference Standard | Low risk of biasc | 0 | ‐ | ‐ | |

| QUADAS Flow and Timing | Low risk of bias | 11 | 0.87 (0.84‐0.90) | 0.57 (0.49‐0.65) |

aThree studies had data points for evaluations with both a lower‐ and a higher‐quality reference standard.

bFive studies had data points at both thresholds: trace and +1.

cInsufficient data for synthesis.

Microhaematuria and proteinuria had higher sensitivity (77% vs 73% and 67% vs 56%) in children than in mixed populations of adults and children. Specificity was higher for microhaematuria (91% vs 82%) but was comparable for proteinuria (81% vs 82%) in children compared with mixed populations of adults and children. All except one study of CCA POC for S. mansoni were carried out with children. At a positivity threshold ≥ 1, sensitivity of CCA POC for S. mansoni was lower (72% vs 89%) and specificity higher (85% vs 55%) than at a positivity threshold of trace positive. In the light‐intensity subgroup, sensitivity was slightly lower for microhaematuria (73% vs 75%) and specificity was slightly higher (88% vs 87%) compared with results of the overall analysis. In contrast, sensitivity (60% vs 61%) and specificity (83% vs 82%) for proteinuria were comparable. Data were insufficient to permit estimation of the sensitivity and specificity of CCA POC for S. mansoni in light‐intensity settings.

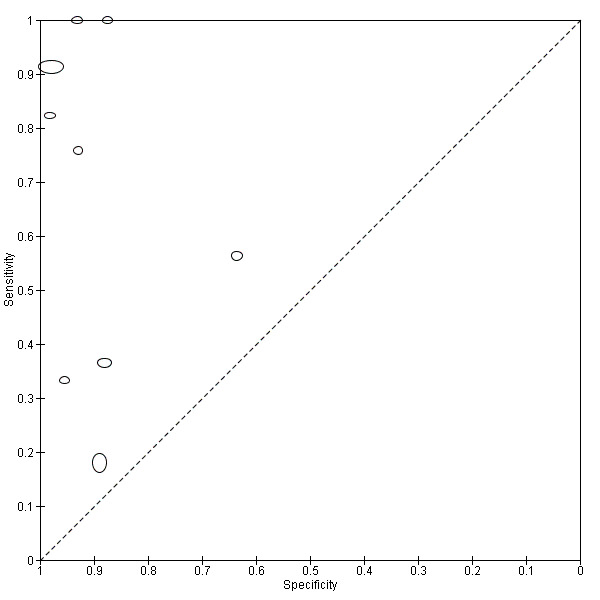

The forest plot (Figure 15) and the ROC plot (Figure 16) demonstrating sensitivity and specificity for microhaematuria after praziquantel treatment show a lot of variation in the estimates (predominantly for sensitivity) of the individual studies.

15.

Forest plot of sensitivity and specificity of the urine reagent strip for microhaematuria for studies done after treatment with praziquantel.

Squares represent the sensitivity and specificity of one study, the black line its confidence interval.

16.

Summary ROC plot of sensitivity and specificity of the urine reagent strip for microhaematuria for studies done after treatment with praziquantel.

The size of the points is proportional to the study sample size

Sensitivity analysis

For microhaematuria, when the analysis was limited to studies that used filtration only as the concentration method for urine microscopy, sensitivity (73% (69% to 78%) vs 76% (72% to 80%)) was lower and specificity was comparable (86% (82% to 89%) vs 86% (82% to 89%)) with those produced by the overall analysis. For proteinuria, when the analysis was limited to studies that used filtration only as the concentration method for urine microscopy, sensitivity was comparable (62% (52% to 71%) vs 61% (53% to 69%) and specificity was lower (80% (73% to 86%) than those produced by the overall analysis (83% (77% to 88%)) (Table 3; Table 4; Table 5).

Sensitivities and specificities of microhaematuria were comparable when analysis was limited to studies with low risk of bias for the participant flow domain. Sensitivity of proteinuria was higher when limited to studies with low risk of bias for the participant selection domain (64%) and the participant flow domain (67%). Specificity on the other hand was comparable for these two domains. Sensitivity and specificity of CCA POC for S. mansoni were comparable when limited to studies with low risk of bias for the participant flow domain (Table 3; Table 4; Table 5). Data were insufficient to allow estimation of sensitivity and specificity for studies with low risk of bias in the other domains—reference standard and participant selection—for the CCA POC test for S. mansoni.

As part of post hoc analyses, we noted that three evaluations showed substantial heterogeneity for the tests microhaematuria (Aryeetey 2000; sensitivity 55%, specificity 36%), proteinuria (Aryeetey 2000; sensitivity 38%, specificity 11%), and CCA POC for S.mansoni (Standley 2010; sensitivity 99%, specificity 19%). We excluded these evaluations in sensitivity analyses for the respective tests and found the following results. Results for microhaematuria (sensitivity 75%, specificity 87%) and proteinuria (sensitivity 61%, specificity 82%) were similar to those of the overall analysis. For CCA POC for S. mansoni, sensitivity was comparable (88% vs 89%) and specificity was slightly higher (58% vs 55%) compared with those of the overall analysis.

Discussion