Abstract

This study was a prospective cohort study to evaluate negative pressure wound therapy (NPWT) with low pressure and a gauze dressing to treat diabetic foot wounds. Thirty patients with diabetic foot wounds were consented to a prospective study to evaluate wound closure and complications to evaluate NPWT with low pressure (80 mmHg) and a gauze dressing interface (EZCare, Smith and Nephew) for up to 5 weeks. NPWT was changed 3 times a week. Study subjects were evaluated once a week for adverse events and wound measurements. Of study subjects, 43% attained at least a 50% wound area reduction after 4 weeks of therapy. Our results suggest that a high rate of wound closure could be expected with low pressure and a gauze interface.

Keywords: diabetes, ulceration, amputation, negative pressure, infection

Negative pressure wound therapy (NPWT) has dramatically changed the treatment of complicated diabetic foot wounds. Randomized clinical trials have shown that NPWT increases the proportion of wounds that heal and the median time to heal.1 Compared to standard wound care, patients treated with NPWT are 1.4 times more likely to heal and 2.5 times less likely to require amputation.1,2 For many years, clinicians were limited to a single vendor for NPWT. Therefore the traditional approach using 125 mmHg pressure and a polyurethane foam dressing was the only treatment described in the literature and taught to clinicians for complex wounds. Pressure setting selection was based on classical swine studies conducted at Wake Forrest University. Morykwas and colleagues reported that local tissue perfusion was optimized at 125 mmHg. Recently, Borgquist and colleagues re-created the swine study and reported that pressures up to 80 mmHg increased local perfusion and higher pressures reduced perfusion.3,4 Borgquist and colleagues also evaluated the effectiveness of foam and gauze dressings. They demonstrated essentially identical results when foam and gauze wound interfaces were used with NPWT in a swine model.5 The purpose of this study was to evaluate the effect of low pressure (80 mmHg) and a gauze wound interface on the percentage wound area reduction in diabetic foot wounds.

Research Design and Methods

This was a prospective, open-label cohort study to evaluate NPWT with low pressure and a gauze dressing to treat diabetic foot wounds. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Scott and White Hospital. We consented and enrolled 30 diabetic patients with foot wounds to receive 80 mmHg of NPWT with a gauze dressing interface for up to 4 weeks, followed by a 1-week posttreatment evaluation (EZCare, Smith and Nephew Medical, London, UK). The NPWT dressing was changed every 3 days. Patients with exposed bone or tendon had exposed areas covered with protective nonadherent gauze prior to application of the dressing and NPWT. The primary outcome was 50% wound area reduction. “Responders” were defined as subjects that achieved at least a 50% wound area reduction after 4 weeks of therapy and “nonresponders” as subjects with <50% wound area reduction. In addition we evaluated the change in wound area and volume over the 4-week study.

Inclusion criteria included subjects with diabetes who were 18 years of age or older and with an acute or surgical wound deemed suitable for treatment with NPWT. We excluded patients with untreated osteomyelitis and presence of necrotic tissue and patients who were pregnant or planning to become pregnant. Patients who interrupted the evaluation treatment for longer than 48 hours were withdrawn from treatment. Digital photos and wound measurements of length, width, and depth were obtained once a week. Photos were taken of each wound at each dressing change. Wound volume was calculated using clinical measurements and the formula for volume of an ellipsoid; the volume is V = 4/3 LWDπ, where L is the length of the long axis, W is the width, and D is the depth. Wound area and volume reduction were calculated as percentage change from baseline wound size. Statistical analysis included 2-way analysis of variance with repeat measures. Patients who received off-loading used either a removable cast boot or a postop shoe based on the patient’s postural stability and wound location. In addition, patients were prescribed wheelchairs, crutches, or canes.

Results

Of the 30 patients enrolled in the study, 63% were male and the average age was 55 ± 11.8 (range 89-32). All of the study subjects had type 2 diabetes and diabetes-related foot wounds, with a mean duration of diabetes of 14.5 ± 10.7 years and a mean glycated hemoglobin of 7.9 ± 1.64. The average size of foot wounds was 8.2 ± 8.1 cm2. During the study there was 1 serious adverse event that was not device related; 20% of patients withdrew from the study, and 13.3% healed. Demographics for responders (≥50% wound area reduction) and nonresponders (<50%) are provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographics.

| Responders (n = 13) | Nonresponders (n = 17) | |

|---|---|---|

| Sex (% male) | 76.9 | 52.9 |

| Age (years) | 54.9 ± 10.6 | 55.1 ± 12.5 |

| Glycated hemoglobin | 8.3 ± 1.5 | 7.6 ± 2.2 |

| VPT | 53.5 ± 12.3 | 56.5 ± 15.4 |

| ABI | 1.02 ± 0.8 | 1.03 ± 0.9 |

| Wound location (%) | ||

| Forefoot | 84.6 | 58.8 |

| Midfoot/heel | 7.7 | 11.8 |

| Dorsal foot | 7.7 | 29.4 |

| Off-loading (%) | ||

| Removable boot | 38.5 | 23.5 |

| Postop shoe | 53.8 | 41.2 |

| Wheelchair | 30.8 | 52.9 |

| Crutch/cane | 7.7 | 5.9 |

Abbreviations: ABI = Ankle Brachial Index; VPT = Vibration Perception Threshold.

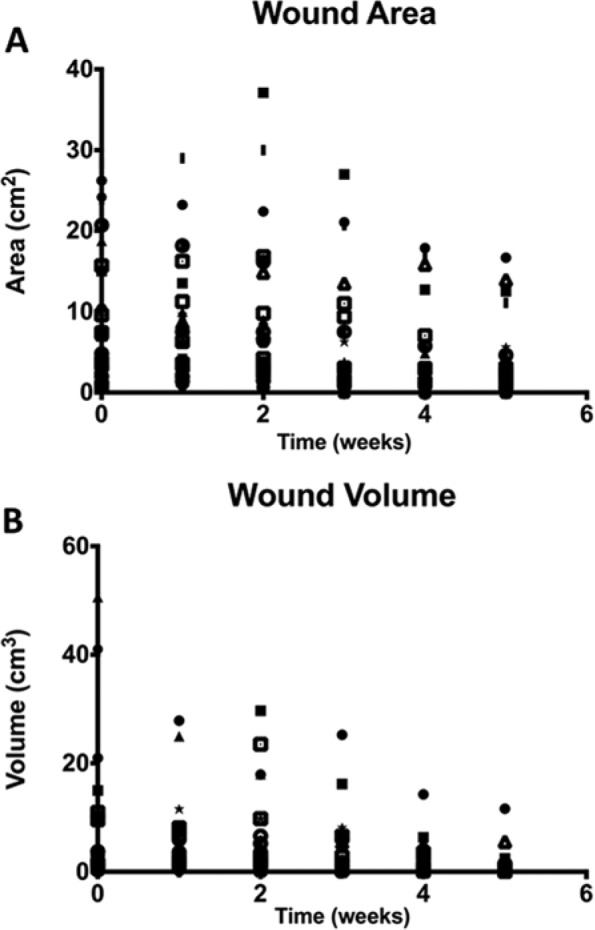

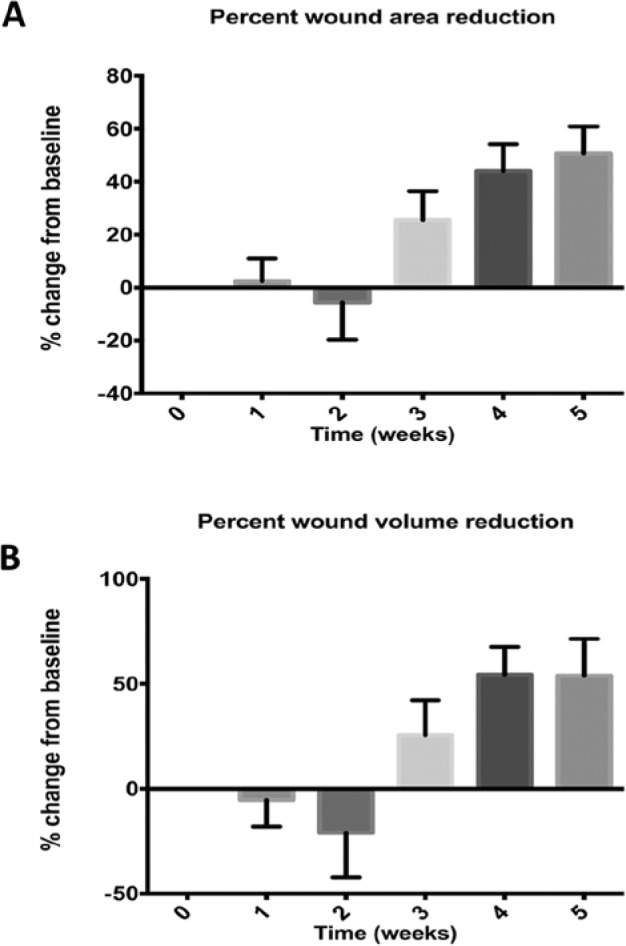

Wound area and volume for each study visit are displayed in Figure 1. Figure 2 shows wound area and volume changes from baseline or all subjects. On average there was an increase in wound volume the first 2 weeks and an increase in wound area the second week.

Figure 1.

Wound size and wound volume for all study subjects.

Figure 2.

Percentage wound area reduction and percentage wound volume reduction compared to baseline for all subjects.

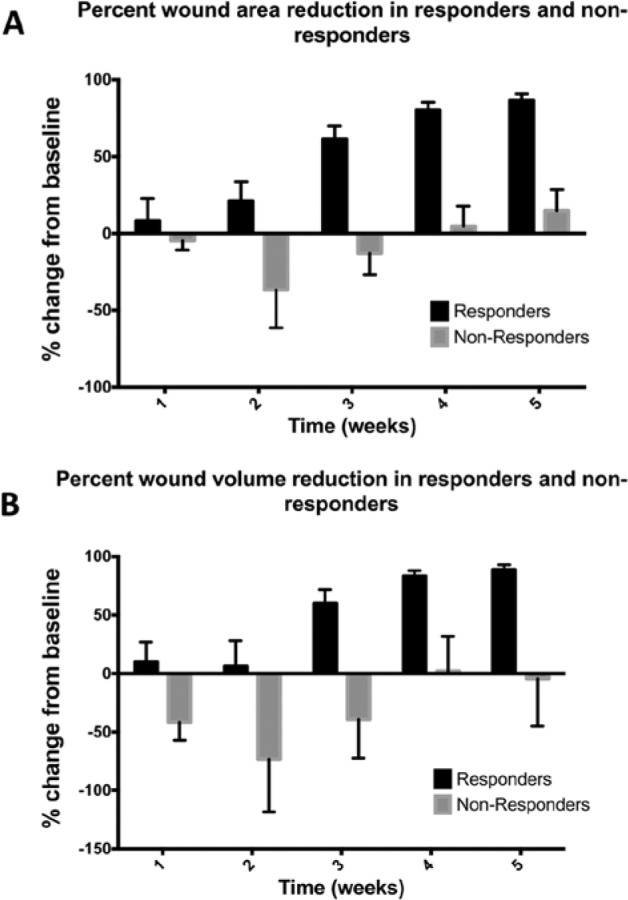

Wound area and wound volume reduction are shown in Figure 3 for responders and nonresponders. We defined responders as subjects that achieved at least a 50% wound area reduction after 4 weeks of therapy; 43.3% of patients achieved this milestone. There was a significant difference in wound area and volume measures among responders and nonresponders during the course of the study (P < .001). A post hoc analysis was then performed using a Sidek test that identified a significant difference in pairwise comparisons at week 3 (P = .01) and week 5 (P = .01) for wound area and wound volume between responders and nonresponders. Figure 3 shows that the mean wound area and wound volume increased the first 3 weeks of therapy in nonresponders.

Figure 3.

Percentage wound area reduction and percentage wound volume reduction compared to baseline for responders and nonresponders. Responders were defined as patients who achieved at least a 50% wound area reduction in 4 weeks. Nonresponders had <50% wound area reduction. Of study subjects, 43% achieved at least a 50% wound area reduction. There was a significant difference between responders and nonresponders in weeks 3 and 5. *P = .01.

Discussion

Several studies have reported the benefit of using a 4-week measurement of wound healing as a surrogate measure of complete wound healing. Cardinal and Sheehan recommended using a 50% wound area reduction at 4 weeks to predict complete wound healing after 12 weeks of therapy in post hoc analysis of phase 3 clinical studies for diabetic foot ulcers. Using a similar approach, Lavery and colleagues reported a strong correlation with 15% wound area reduction after 1 week and a 60% wound area reduction after 4 weeks in patients that were treated in a 16-week randomized clinical trial (RCT) of NPWT. The advantage of using a surrogate marker for 4 weeks is the savings that can be realized by conducting a study that is only 25% as long as the traditional 12-week evaluation period. In addition, studies can be executed faster. As a mechanism to establish “proof of concept,” surrogate markers seem reasonable. However, short evaluation periods do not allow investigators to evaluate device-related complications, adverse events, compliance, or cost.

In this study we evaluated both changes in wound area as well as wound volume. At least a 50% wound area reduction was noted in 43% of study subjects by 4 weeks. If wound changes at 4 weeks can be used as an accuratesurrogate marker for compete closure, our results appear to be similar to diabetic foot ulcer studies that evaluated platelet derived growth factor (50% wound healing),6 bioengineered tissue (30%-56% wound healing),7,8 and NPWT (43%-56% wound healing).2 NPWT may be most valuable to treat deep complex wounds in which bone, tendon and fascia are exposed. No other studies have considered “wound volume reduction” as a surrogate marker for complete wound healing, but this is probably because most phase 3 clinical trials have been conducted in University of Texas Ulcer Classification 1A wounds.9,10 These wounds usually are not deep, and measures of area are probably the most useful primary endpoint. Among nonresponders, the mean wound area and wound volume increased the first 3 weeks of therapy, so a negative response in the first week or 2 of therapy may indicate that the therapy may not be successful.

There are certainly limitations to this study. It is a prospective, open-label cohort study, so there are no treatments to compare. And a surrogate marker was used to evaluate the effectiveness of the therapy rather than complete wound healing. Our results provide a preliminary look at this approach to establish its validity. These results should provide the building blocks for head-to-head comparisons, so clinicians have a more in-depth understanding of the types of wounds that low and high pressure and gauze and foam interfaces work the best. There are currently no clinical studies that directly compare NPWT with low pressure and gauze and low pressure and foam, or high pressure and gauze and high pressure and foam. Industry has been reluctant to fund these studies because they are very expensive, and they do not see a strong justification to improve their bottom line. Federal funding agencies such as the National Institutes of Health and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality see this as commercial development, with only an incremental increase in scientific knowledge.

Using low pressure and a gauze wound dressing contradicts what nurses, therapists, and physicians have regarded as the pillar of the faith in NPWT. The application process using gauze or a foam-based dressing is similar. There are no nuisances or a learning curve to the application. Gauze may be a less expensive dressing, but the savings of a dressing pack are relatively small if the application is not as effective as foam. It is unclear if there is an advantage to using a low pressure and gauze dressing compared to high pressure and gauze or low pressure and foam. Head-to-head comparisons need to be completed to answer these questions. We have been taught to regard polyurethane foam dressings as 1 of the keys to achieving uniform pressure within the wound bed, and uniform pressure was thought to be essential to the success of NPWT. Whether gauze provides uniform pressure or not seems moot. The clinical results suggest the NPWT that uses low pressure and a gauze interface is effective and safe. We need to evaluate this approach as part of a systematic assessment of NPWT in complex wounds. Like many early cohort studies, this study’s purpose was to evaluate the effect of low pressure (80 mmHg) and a gauze wound interface on the percentage wound area reduction in diabetic foot wounds and collect some observational data on this approach. The results were good, with 43.3% of subjects achieving at least a 50% wound area reduction in 4 weeks. This is certainly similar to other NPWT study results.1,2 They were neither earth-shattering nor disappointing. The approach certainly warrants more research to help us understand the advantages and disadvantages of low pressure and gauze with NPWT.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: D, depth; NPWT, negative pressure wound therapy; RCT, randomized clinical trial; V, volume; W, width.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared the following potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: LAL has research funding from Smith and Nephew, KCI, Innovative Therapies Inc, Convatec and Thermoteck; is on the Scientific Advisory Board of Innovative Therapies Inc; and is part of the Speaker’s Bureau of Smith and Nephew. DPM has research funding from Smith and Nephew. PJK has research funding from KCI. JL has research funding from Smith and Nephew, KCI, Innovative Therapies Inc, and Convatec and is part of the Speaker’s Bureau of Shire and Smith and Nephew. KED has research funding from Innovative Therapies Inc, Convatec, and Thermoteck.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This project was funded by a grant from Smith and Nephew.

References

- 1. Armstrong DG, Lavery LA. Negative pressure wound therapy after partial diabetic foot amputation: a multicentre, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2005;366(9498):1704-10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Blume PA, Walters J, Payne W, Ayala J, Lantis J. Comparison of negative pressure wound therapy using vacuum-assisted closure with advanced moist wound therapy in the treatment of diabetic foot ulcers: a multicenter randomized controlled trial. Diabetes Care. 2008;31(4):631-636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Borgquist O, Ingemansson R, Malmsjo M. The influence of low and high pressure levels during negative-pressure wound therapy on wound contraction and fluid evacuation. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2011;127(2):551-559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Borgquist O, Ingemansson R, Malmsjo M. Wound edge microvascular blood flow during negative-pressure wound therapy: examining the effects of pressures from −10 to −175 mmHg. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2010;125(2):502-509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Borgquist O, Gustafsson L, Ingemansson R, Malmsjo M. Micro- and macromechanical effects on the wound bed of negative pressure wound therapy using gauze and foam. Ann Plast Surg. 2010;64(6):789-793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Wieman TJ, Smiell JM, Su Y. Efficacy and safety of a topical gel formulation of recombinant human platelet-derived growth factor-BB (becaplermin) in patients with chronic neuropathic diabetic ulcers. A phase III randomized placebo-controlled double-blind study. Diabetes Care. 1998;21(5):822-827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Veves A, Falanga V, Armstrong DG, et al. Graftskin, a human skin equivalent, is effective in the management of noninfected neuropathic diabetic foot ulcers: a prospective randomized multicenter clinical trial. Diabetes Care. 2001;24(2):290-295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Marston WA, Hanft J, Norwood P, et al. The efficacy and safety of Dermagraft in improving the healing of chronic diabetic foot ulcers: results of a prospective randomized trial. Diabetes Care. 2003;26(6):1701-1705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Armstrong DG, Lavery LA, Harkless LB. Validation of a diabetic wound classification system. The contribution of depth, infection, and ischemia to risk of amputation. Diabetes Care. 1998;21(5):855-859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lavery LA, Armstrong DG, Harkless LB. Classification of diabetic foot wounds. Ostomy Wound Manage. 1997;43(2):44-48, 50,, 52-53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]