Abstract

The dose response of postprandial plasma glucose (PPG) to add-on, premeal oral hepatic-directed vesicle-insulin (HDV-I), an investigational lipid bio-nanoparticle hepatocyte-targeted insulin delivery system, was evaluated in a 3-test-meal/day model in type 2 diabetes patients. The single-blind, placebo-controlled, dose-escalating trial enrolled 6 patients with HbA1c 8.6 ± 2.0% (70.0 ± 21.9 mmol/mol) and on stable metformin therapy. Patients received oral HDV-I capsules daily 30 minutes before breakfast, lunch, and dinner as follows: placebo capsules, 0.05, 0.1, 0.2, and 0.4 U/kg on days 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5, respectively. Outcome measures were PPG and incremental PPG area under the concentration-time curve (AUC). All 4 doses of oral HDV-I statistically significantly lowered mean PPG (P ≤ .0110 each) and incremental PPG (P ≤ .0352 each) AUC compared to placebo. A linear dose response was not observed. The 0.05 U/kg dose was the minimum effective dose in the dosage range studied. Three adverse events unrelated to treatment were observed. Add-on oral HDV-I 0.05-0.4 U/kg significantly lowered PPG excursions and the dose response curve was flat. These results are consistent with the lack of a linear dose response between portal and systemic plasma insulin concentrations in previous animal and human studies. Oral HDV-I was safe and well tolerated.

Keywords: oral, insulin delivery system, hepatic-directed vesicle insulin, type 2 diabetes, dose response, postprandial plasma glucose

Intensive glycemic therapy can significantly reduce the risk of microvascular (retinopathy and, nephropathy) and neuropathic complications in type 2 diabetes patients.1,2 Since type 2 diabetes mellitus is a progressive disease, patients will ultimately require the addition of insulin to their oral antidiabetic drugs (OADs) as β-cell function declines over time and insulin secretion declines.1,3,4 Despite the known benefits and potential advantages of intensive glycemic control in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus, insulin treatment is often initiated late in the course of the disease following the failure of OADs or for a variety of other reasons, including fear of injections, weight gain, and hypoglycemia; fear of disease progression; patient and/or physician misperceptions about insulin; the unwillingness of physicians and their patients to initiate insulin therapy according to conventional recommendations referred to as “psychological insulin resistance”; and so on.5-7 Therefore, alternative less-intrusive and noninvasive routes of insulin administration are being developed8-11 to overcome these problems. Of the noninvasive routes, the oral route of insulin delivery holds the greatest promise because it utilizes the hepatic-portal route and hence, more closely approximates the physiological delivery of insulin to the liver and peripheral tissue.

Oral hepatic-directed vesicle-insulin (HDV-insulin or HDV-I) is an investigational lipid bio-nanoparticle hepatocyte-targeted insulin drug delivery system (Diasome Pharmaceuticals, Inc, Cleveland, OH, USA)12 designed to reestablish the normal insulin physiological responses in the liver in patients with type 1 or type 2 diabetes mellitus. The drug product consists of insulin incorporated into a <150 nm lipid bio-nanoparticle with a surface-located proprietary hepatocyte-targeting molecule (HTM). The HTM facilitates the capture of the HDV-I by the hepatocytes following uptake from the gut through the hepatic-portal vein after oral administration. The high bioefficacy of peripherally infused HDV-I compared to regular insulin (RI) was previously demonstrated in a hepatic glucose balance study in diabetic dogs. In that study, both RI and HDV-I infused into glucose-loaded diabetic dogs at various doses via the external jugular vein converted hepatic glucose output to hepatic glucose uptake. However, HDV-I produced its effect at the much lower doses (range: 0.025 to 0.4 mU/kg/min), including a dose that was <1% of the only dose of RI (6.25 mU/kg/min) that was efficacious. This dose was not accompanied by measurable (by standard radioimmunoassay) increases in portal insulin levels, as contrasted with efficacious peripheral regular insulin.12 Based in part on these results demonstrating the high bioefficacy of intravenous HDV, it was suspected HDV-I could be effective in patients with diabetes even with oral administration. Other observations supporting this expectation included the results of studies conducted using HDV-I (subcutaneously and orally) in various animal models of diabetes and of the Phase II clinical trials in patients with diabetes demonstrating significantly improved glycemic control during an oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) and administration of diabetic meals.12-15

The objective of this study was to evaluate the dose response of postprandial plasma glucose lowering to escalating premeal single doses of add-on oral HDV-I in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus on stable OADs in a 3-meal-per-day inpatient model.

Methods

The study was conducted at a single study center, the Diabetes and Glandular Research Associates, San Antonio, Texas. The study protocol and amendment, and informed consent were approved by an independent Research Ethics Board. The study was conducted in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki and its amendments, and the International Conference on Harmonization (ICH) Good Clinical Practice (GCP) guidelines. The ClinicalTrials.gov identifier was NCT0052178. Every patient provided a written informed consent prior to participation in the study.

Subject Selection

Adult males and females between the ages of 18 and 65 years inclusive, with a current diagnosis of type 2 diabetes mellitus and which was managed with OADs for at least a 3-month duration were enrolled into the study. Patients were also required to have no clinically significant abnormalities during a physical examination, have a glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) level ≥ 8 to ≤ 12% (≥ 64.0 to ≤ 108.0 mmol/mol), BMI ≤ 38 kg/m2, C-peptide level > 3 ng/ml, and a fasting plasma glucose level ≤ 200 mg/dl. In addition, female patients of childbearing potential were to have a negative pregnancy test at randomization and should be using a reliable form of birth control during the study.

Major exclusion criteria included patients with a history or presence of significant cardiac, gastrointestinal, endocrine, neurological, hepatic or renal disease, or conditions known to interfere with the absorption, distribution, metabolism, or excretion of insulin. Also excluded were patients who required the regular use of medications that interfered with the absorption and/or metabolism of insulin; patients who within 48 hours of dosing used medications that interfered with plasma glucose analyses, including mannose, acetaminophen, dopamine, and ascorbic acid; and patients who used Avandia® or Actos® for treating their type 2 diabetes or used monoamine oxidase (MAO) inhibitors or enzyme-inducing or enzyme-inhibiting agents (eg, phenobarbital or carbamazepine) within 30 days prior to admission into the study.

Study Design

The study was a single-blind, placebo-controlled, dose-ranging trial of add-on oral HDV-I administered prior to meals, in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus on OADs in a 3-test meal per day model. Patients were assigned sequentially to the order of treatment as follows: day 1, oral placebo capsules; day 2, oral HDV-I 0.05 U/kg; day 3, oral HDV-I 0.1 U/kg; day 4, oral HDV-I 0.2 U/kg; and day 5, oral HDV-I 0.4 U/kg.

Study Procedure

Following screening, patients stayed on their usual dietary routine until 3 days before initiation of treatment when they were maintained on a standardized diabetic diet of 250 g of carbohydrate per day (to provide a caloric requirement of 2000 Kcal per day and a composition of 55% CHO, 30% fat and 15% protein per meal) plus their on-going OADs, and were also instructed to avoid any strenuous physical activity and hypoglycemic events. Patients were required to meet the goal of a fasting plasma glucose (FPG) level of ≤200 mg/dl during the 2 days prior to the initiation of treatment. Each eligible patient was admitted to the metabolic ward (study center) at 6:00 p.m. ± 1 h on the evening before the Treatment Period, provided a 60 g carbohydrate dinner, and then placed on an overnight intravenous (IV) regular insulin drip, using a standard insulin drip protocol, so that the morning FPG level was approximately 100 mg/dl. The IV insulin drip was administered the night before each treatment day and was withdrawn 1 hour before beginning each treatment. The subjects were maintained on their usual OADs during the 5-day treatment period.

During the Treatment Period, patients received study medications each morning 1 hour after removing the IV insulin drip. Thirty minutes after dosing, subjects received a 60 g carbohydrate breakfast to be consumed within 30-45 minutes postdosing and the dosing was repeated 30 minutes before lunch and dinner on each day. Peripheral venous blood was sampled according to a prespecified schedule from 30 minutes before dosing at breakfast to 4.5 hours after dinner (−30 to 810 minutes) for the estimation of plasma glucose levels. Following the completion of treatment and assessments on day 5, patients had a follow-up visit on the same day that included an abbreviated physical examination and the collection of blood and urine samples for clinical laboratory tests.

Treatments

Study medications were supplied as follows: (1) oral HDV-I 0.1 U/kg—comprising HTM biotin-phosphatidylethanolamine (HTM-B) with 1.1 mg of HDV-phospholipid per unit of insulin in 2 U and 4 U capsules. There was no rounding to the nearest whole capsule. Patients consumed an extra 2 U capsule should the body weight calculation require more than a full 4 U capsule. (2) Placebo capsules—contained gelatin USP.

Outcome Parameters

The primary efficacy parameter was comparison of postprandial glycemic control, as indicated by the plasma glucose area under the concentration-time curves (AUCs) following dosing, between the doses of oral HDV-I and placebo. The secondary efficacy and safety parameters included comparison of incremental plasma glucose AUCs; and tolerability and patient acceptance of oral HDV-I by comparing the incidence of treatment-related hypoglycemic, serious adverse, and nonserious adverse events with that of placebo.

Statistical Methods

Mean plasma glucose and incremental plasma glucose AUCs were obtained from plots of the mean plasma glucose and incremental plasma glucose concentrations versus time, respectively, using a computer software program, SlideWrite Plus for Windows version 7.0 (Advanced Graphics Software, Inc, Encinitas, CA, USA), which calculates AUC based on the trapezoidal rule. The mean incremental plasma glucose AUC values for each meal was calculated from segments of the mean incremental plasma glucose versus time profiles as follows: breakfast AUC0-270 min, lunch AUC270-540 min, and dinner AUC540-810 min. The reference point used for computing the incremental plasma glucose values was the −30 minute point of the plasma blood glucose measurements. The−30 minute time point value was therefore set to zero. The analysis of the primary efficacy and secondary parameters included all patients enrolled into the study with complete data. Mean plasma glucose and incremental plasma glucose AUC values were compared between doses of oral HDV-I and placebo using the paired Student’s t test. A P value ≤ .05 was considered statistically significant. Adverse events were coded using the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities (MedDRA).

Results

Fourteen patients were screened for the study; 7 patients were enrolled and were all on stable doses of metformin treatment at baseline. One patient was discharged from the study by the investigator after receiving day 1 (placebo) treatment due to high blood pressure. Therefore, 6 subjects (3 males and 3 females) received all treatments, and completed the study. The patients’ demographics and baseline characteristics are summarized in Table 1. The mean ± SD baseline fasting plasma glucose values for all subjects before administration of treatment were 123.8 ± 15.9, 120.8 ± 10.0, 122.8 ± 13.5, 113.2 ± 16.0, and 112.2 ± 16.8 mg/dl on treatment days 1 (placebo), 2 (0.05 U/Kg), 3 (0.1 U/Kg), 4 (0.2 U/Kg), and 5 (0.4 U/Kg), respectively. There were no statistically significant differences between the baseline mean plasma glucose values on days 1 to 5.

Table 1.

Patient Demographics and Baseline Characteristics.

| Characteristic/Parameter | Male (n = 3) | Female (n = 3) | Total (n = 6) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | |||

| Mean ± SD | 55.3 ± 9.8 | 56.3 ± 6.1 | 55.8 ± 7.3 |

| Weight (kg) | |||

| Mean ± SD | 79.1 ± 14.7 | 70.0 ± 9.1 | 74.6 ± 12.0 |

| Height (cm) | |||

| Mean ± SD | 166.7 ± 4.7 | 161.6 ± 4.6 | 164.1 ± 5.0 |

| Body Mass Index (kg/m2) | |||

| Mean ± SD | 28.2 ± 3.8 | 26.9 ± 4.1 | 27.6 ± 3.6 |

| Gender | |||

| n (%) | 3 (50.0%) | 3 (50.0%) | 6 (100.0%) |

| Ethnic Group | |||

| Hispanic | 3 (100.0%) | 2 (66.7%) | 5 (83.3%) |

| Caucasian | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (33.3%) | 1 (16.7%) |

| HbA1c (%) | |||

| Mean ± SD | 8.4 ± 2.8 | 8.8 ± 1.5 | 8.6 ± 2.0 |

| C-peptide (ng/ml) | |||

| Mean ± SD | 3.6 ± 1.6 | 3.9 ± 0.6 | 3.7 ± 1.1 |

| Baseline (fasting) blood glucose (mg/dl) | |||

| Mean ± SD | 118.3 ± 14.7 | 129.3 ± 17.9 | 123.8 ± 15.9 |

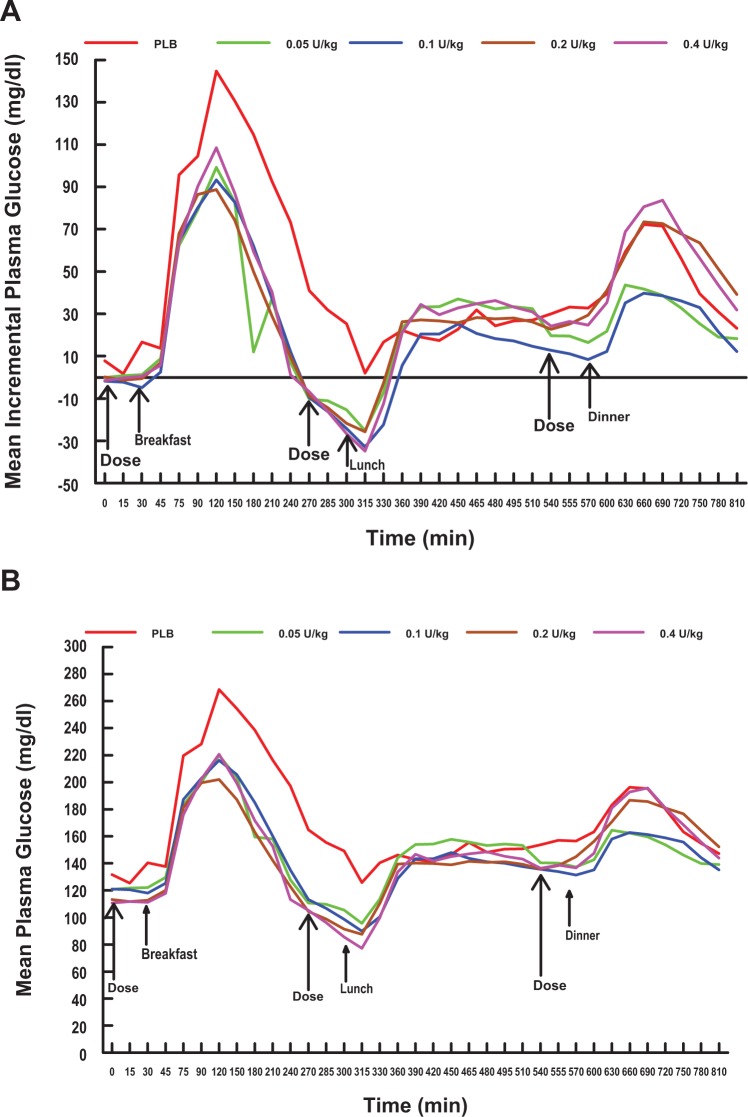

Plasma Glucose Versus Time Curves

Overall, the mean and incremental postprandial plasma glucose excursions induced by the meals and following all treatments including placebo were largest at breakfast, intermediate at dinner, and lowest at lunch (Figures 1A and 1B and Table 2). Following the 60 g carbohydrate breakfast, all 4 doses of oral HDV-I reduced the mean incremental plasma glucose excursions to similar peak levels (99.2, 93.3, 88.8, and 108.5 mg/dl for the 0.05, 0.1, 0.2, and 0.4 U/kg doses, respectively) at 90 minutes after the meal (or 120 minutes in Figure 1A). In contrast, the placebo mean incremental plasma glucose rose more rapidly, as expected, to a higher peak level (144.7 mg/dl) at 90 minutes. Following lunch and dinner, the incremental plasma glucose excursions associated with all treatments peaked at between 150 to 165 minutes (or 450-465 minutes in Figure 1A) and had similar peaks (range 25.2-34.8 mg/dl), and between 60 to 120 minutes (or 630-690 minutes in Figure 1A), after the meals, respectively. After dinner, peaks of the curves for the 0.05 and 0.1 U/kg doses were lower than that of placebo.

Figure 1.

Mean incremental plasma glucose (A) and plasma glucose (B) versus time profiles by treatment and dose. The mean incremental plasma glucose (A) and plasma glucose (B) versus time profiles during the administration of 0.05 (green lines), 0.1 (blue lines), 0.2 (brown lines), and 0.4 (magenta lines) U/kg premeal single doses of oral HDV-insulin and placebo (red lines) over the 3-meal (810 minutes) test period. All 4 doses of oral HDV-insulin were associated with significantly lower incremental plasma glucose (A) and plasma glucose (B) excursions following breakfast compared to placebo and attained a peak at 90 minutes after the meal. At lunch and dinner, there were reductions in postprandial plasma glucose and incremental plasma glucose excursions by all 4 doses of oral HDV-insulin compared to placebo, however, the reductions were not significantly different. HDV = Hepatic-directed vesicle.

Table 2.

Mean ± SD Incremental Glucose AUC Over 2 and 4 Hours Postdosing, P Values for Comparison of Means and Percentage Reduction Versus Placebo by Meal for the Doses of Oral HDV-Insulin.

| AUC0-2 h

|

AUC0-4 h

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatments (dose of oral HDV-I) | Mean (mg.min/dl) | P value vs placebo | % reduction vs placebo | Mean (mg.min/dl) | P value vs placebo | % reduction vs placebo | AUC0-2 h as % of AUC0-4 h |

| Breakfast | |||||||

| Placebo | 11 240 ± 658 | N/A | N/A | 22 449 ± 1103 | N/A | N/A | 50.1 |

| 0.05 U/kg | 7610 ± 1161 | 0.0245 | 32.3 | 10 407 ± 2304 | 0.0017 | 53.6 | 73.1 |

| 0.1 U/kg | 7317 ± 1223 | 0.0104 | 34.9 | 11 682 ± 2973 | 0.0044 | 48.0 | 62.6 |

| 0.2 U/kg | 7404 ± 1732 | 0.0416 | 34.1 | 11 021 ± 4059 | 0.0229 | 50.9 | 67.2 |

| 0.4 U/kg | 8154 ± 1024 | 0.0081 | 27.5 | 12 377 ± 2078 | 0.0005 | 44.9 | 65.9 |

| Lunch | |||||||

| Placebo | 2097 ± 658 | N/A | N/A | 6036 ± 6266 | N/A | N/A | 34.7 |

| 0.05 U/kg | 1544 ± 658 | NS | 26.4 | 5059 ± 5301 | NS | 16.2 | 30.5 |

| 0.1 U/kg | −79 ± 3034 | NS | 103.8 | 1671 ± 6531 | NS | 72.3 | 104.7 |

| 0.2 U/kg | 1394 ± 2156 | NS | 33.6 | 4120 ± 4607 | NS | 31.7 | 33.8 |

| 0.4 U/kg | 1116 ± 1547 | NS | 46.8 | 4434 ± 3564 | NS | 26.5 | 25.2 |

| Dinner | |||||||

| Placebo | 6697 ± 4075 | N/A | N/A | 12 892 ± 7104 | N/A | N/A | 51.9 |

| 0.05 U/kg | 4045 ± 2156 | NS | 39.6 | 7781 ± 4773 | NS | 39.6 | 52.0 |

| 0.1 U/kg | 3325 ± 3245 | NS | 50.4 | 7135 ± 7097 | NS | 44.7 | 46.6 |

| 0.2 U/kg | 6405 ± 2812 | NS | 4.6 | 14 285 ± 5858 | NS | −10.8 | 44.8 |

| 0.4 U/kg | 7170 ± 2148 | NS | −7.1 | 14 726 ± 4921 | NS | −14.2 | 48.7 |

The largest reductions in mean incremental glucose AUC occurred at breakfast. The lower doses of oral HDV-I were generally associated with the larger reductions in incremental plasma glucose AUC at breakfast, lunch, and dinner. Only the mean reductions in incremental glucose AUC at breakfast were significantly different from the corresponding placebo mean value starting at 2 hours postprandial and increasing in magnitude at 4 hours postprandial. % reduction vs placebo was calculated as follows: mean oral HDV-I minus mean placebo ÷ mean placebo × 100%. AUC, area under the concentration-time curve (of the incremental plasma glucose versus time plots); HDV-I, hepatic-directed vesicle-insulin; N/A, not applicable; NS, not significant.

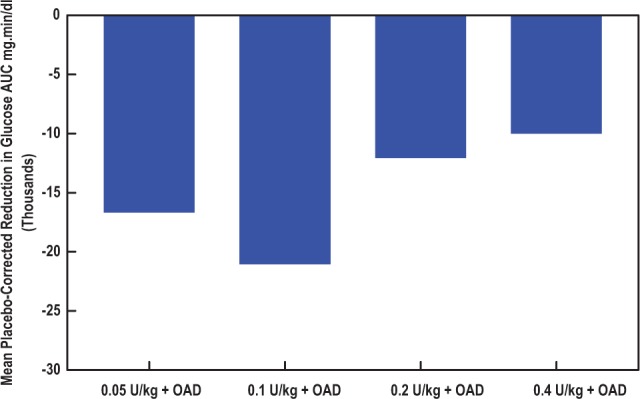

Incremental Plasma Glucoseand Plasma Glucose AUC

All 4 doses of oral HDV-I showed statistically significant reductions in mean incremental glucose AUC, the primary outcome variable, compared to placebo (P ≤ .0352 for each comparison) (Figure 2A) and the pattern of the changes seen with increase in mean incremental glucose AUC were similar to the results obtained for mean plasma glucose AUC (P ≤ .0110 for each comparison versus placebo) (Figure 2B).

Figure 2.

Mean ± SEM incremental plasma glucose (A) and plasma glucose (B) AUC0-810 min values by treatment and dose. Asterisks indicate significant differences (**P ≤ .01 and *P < .05, in each case) of mean plasma glucose and incremental plasma glucose AUC versus the corresponding value for the Placebo + OAD treatment. In pairwise comparisons, a statistically significant difference (P = .0059) in the mean incremental glucose AUC values was obtained only between the mean values for the 0.1 versus 0.2 U/kg doses (A). AUC, area under the plasma glucose concentration-time curve; OAD, oral antidiabetic drug.

In pairwise comparisons between the mean incremental glucose AUC values for the different doses of Oral HDV-I, a statistically significant difference was only obtained between the mean values for the 0.1 versus 0.2 U/kg dose comparison (P = .0059). The results of the pairwise comparisons between the mean incremental glucose AUC values for the 0.05 versus 0.4 U/kg (P = .0772) and 0.1 versus 0.4 U/kg (P = .0687) doses approached but did not achieve statistical significance.

Incremental Plasma Glucose AUC by Meals

Following breakfast, all 4 doses of HDV-I significantly reduced mean incremental plasma glucose AUC at 2 hours postprandial compared to placebo (AUC0-2 h vs placebo; P ≤ .0416 in each case) and the reductions increased and remained significant at 4 hours postprandial (AUC0-4 h vs placebo; P ≤ .0229 in each case) (Table 2). Furthermore, for the 4 doses of oral HDV-I, 63-73% of the 4-hour postbreakfast reduction in mean incremental plasma glucose AUC had occurred already by 2 hours postprandial, compared to only 50% with the placebo treatment (Table 2). Following lunch and dinner, there were reductions in incremental plasma glucose AUC values by all 4 doses of oral HDV-I, however, the reductions were not significantly different from placebo at 2 or 4 hours postprandial.

Dose Response of Plasma Glucose Reductions to Oral HDV-Insulin

All 4 doses of oral HDV-I consistently and significantly reduced incremental glucose AUC0-810 min, compared to placebo over the 3-meal (810 minutes) test period (Figures 2A, 2B, and 3). A linear glucose-lowering dose response effect was not observed in the dosage range studied. Therefore, the minimum effective dose in the dosage range studied was 0.05 U/kg.

Figure 3.

Mean placebo-corrected incremental plasma glucose reductions in AUC0-810 min by dose of add-on oral HDV-insulin. There was an increase in the reductions in mean placebo-corrected incremental plasma glucose levels from the 0.05 U/kg dose of oral HDV-insulin to a maximum effect at the 0.1 U/kg dose. Further increases in dose were associated with significant but progressively lower reductions in mean placebo-corrected incremental plasma glucose levels. All mean incremental plasma glucose reductions were statistically significantly different from placebo before placebo correction. AUC, area under the incremental plasma glucose concentration-time curve; HDV, hepatic-directed vesicle; OAD, oral antidiabetic drug.

Safety Results

There were no unexpected or serious adverse events or hypoglycemic events during the study. Overall, 7 nonserious adverse events were reported in 3 patients and none was considered to be related to the study medication. In 3 patients, 4 adverse events occurred while on placebo treatment and included headache (2 cases), itching left ear, and hyperglycemia. The 3 treatment-emergent adverse events occurred in the same subject during oral HDV-I 0.4 U/kg treatment and included right and left forearm IV infiltrate and right forearm IV site tenderness. No adverse events were reported during any other treatments.

Discussion

The liver normally clears a significant and variable 40 to 80% of the insulin presented to it during first pass.16-18 Hence, the concentration of insulin in the hepatic portal vein is approximately 2 to 3 times higher than the concentration in the peripheral circulation.16,19 Physiologically, this porto-systemic insulin concentration gradient serves to control postprandial plasma glucose levels by directly suppressing hepatic glucose production and increasing hepatic glucose uptake, while minimizing peripheral insulinization. However, in the diabetic subject with a lack of or inadequate insulin production, replacing insulin by conventional SC insulin administration into the peripheral circulation results in adequate glycemic control at the expense of marked peripheral hyperinsulinemia,20-22 which can increase muscle insulin resistance in both type 1 and 2 diabetes.23 This excess peripheral insulin exposure further aggravates the insulin resistance that already exists in type 2 diabetes. Peripheral hyperinsulinemia is associated with adverse metabolic effects,24 atherosclerosis,25 certain types of cancer,26 and is a risk factor for hypoglycemia. Shishko et al have reported that a significantly lower dose of intraportal insulin was required and it more rapidly and significantly lowered plasma glucose with associated lower (only one-third) levels of fasting plasma hyperinsulinemia compared to peripheral insulin administration over a 4-month treatment period in patients with type 1 diabetes.21 Presumably, the oral route of insulin administration would avoid the disadvantages of hyperinsulinism by approximating the physiological route of insulin delivery through the portal vein and thereby restoring the porto-systemic insulin concentration gradient.16,19 The objective of this study was to evaluate the dose response of this orally administered bio-nanoparticle hepatocyte-targeted insulin product.

Our results have shown that add-on oral HDV-I, in the dosage range 0.05 to 0.4 U/kg studied, significantly reduced mean postprandial plasma glucose AUC values, compared to placebo, in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus on OAD. The reason for the lack of a dose response and for the larger effect during breakfast compared to lunch and dinner following the administration of oral HDV-I in this study in patients with type 2 diabetes is not precisely known. However, these results are consistent with the results of a previous hepatic glucose balance study in diabetic dogs that showed all the very small doses of peripherally infused HDV-I (0.025 to 0.4 mU/kg/min), converted hepatic glucose output to hepatic glucose uptake in a dose-independent manner.12 Heinemann and Jacques have suggested that the pattern of the reductions in glycemia seen in this dose response study may be due to the maxing out of the maximum insulin carrying capacity by 0.1 U/kg or maxing out of the suppressive effect of the absorbed insulin on hepatic glucose production.11 In addition, the results of a recently completed dose timing study of oral HDV-I relative to meals may provide an explanation in part for the lack of a linear dose response. The results of the study revealed that administration of oral HDV-I 15 minutes prior to meals was the optimal time of administration as it most markedly and significantly induced a 73% reduction in postprandial plasma glucose excursions, compared to placebo, followed by the −30 minute (60% reduction) and then the 0 minute (39% reduction) dose timings.27 In this study, oral HDV-I was administered 30 minutes before meals.

The availability of pharmacokinetic data following the administration of oral HDV-I may help explain the lack of a dose response and/or the reason for the lack of an increased glucose-lowering response during lunch and dinner compared to breakfast. However, pharmacokinetic data for this product is not accessible in humans, since it can only be measured by sampling portal blood. Second, we have not been able to measure portal plasma insulin levels following the administration of intravenously infused HDV-I in hepatic glucose balance studies in dogs using standard radioimmunoassay.12 This is most likely because oral HDV-I is designed to selectively accumulate in the hepatocytes of the liver, and biodistribution studies of HDV and HDV-I in mice and rats using 5 nm gold particles and a silver enhancement technique have confirmed this specificity with an approximately 80% hepatic accumulation of the injected doses by 60 minutes.12,13 Essentially, all of the injected HDV and HDV-I is eventually extracted by the liver. Clinically, following administration, oral HDV-I is expected to be absorbed from the small intestine into the portal circulation through which it is carried to the liver. Due to the fact that at least 50% and up to 80% of the insulin that reaches the liver is degraded inside the liver (first-pass hepatic insulin extraction),18,28-30 measurements of insulin levels in the peripheral blood after administration of an oral insulin formulation do not reflect the pharmacokinetic (PK) properties in the same manner that we are used to with SC insulin administration.11 However, since these are type 2 diabetes patients who are already hyperinsulinemic, which would make the detection of changes in peripheral insulin essentially impossible, measuring the peripheral insulin levels would be useful in showing that the effect of oral HDV-I was not peripheral. Furthermore, there are virtually no investigations of the dose response of peripheral plasma insulin and glucose levels to intraportally administered insulin in diabetic patients and animal models, largely because insulin is still administered peripherally by SC injection.

Overall, only 3 treatment-unrelated adverse events occurred during treatment with oral HDV-I 0.4 U/kg in the same patient. There were no serious adverse events, episodes of hypoglycemia or clinical laboratory test results suggestive of hypoglycemia during the study. These safety results indicate add-on oral HDV-I 0.05-0.4 U/kg was safe and generally well tolerated. The components of HDV (lipid bio-nanoparticles) and HTM which include cholesterol and phospholipids, known major components of cell membranes, and biotin (a vitamin)12 are all naturally occurring in the human body and do not pose any toxicological risk to the patient.

This study has additional limitations that include small sample size (pilot study), short duration of treatment, single-blind design, and lack of randomization of treatment assignment. However, because the efficacy variable assessed, plasma glucose level, is an objective measure, it is unlikely that the single-blind design and sequential treatment assignment affected the results of the study. Larger, randomized, double-blind, longer-term studies utilizing change in HbA1c as the primary endpoint are required to establish oral HDV-I as an effective, noninvasive, long-term treatment for blood glucose control in patients with type 2 diabetes. Dose response studies using lower doses of oral HDV-I would also be useful in helping it realize its potential of increased patient compliance and adherence to therapy from the convenience of oral dosing.

Conclusions

In conclusion, add-on oral HDV-I across all the doses tested resulted in clinically meaningful reductions in postprandial plasma glucose AUC in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus on stable OAD therapy over the 3-meal study period. The observed flat dose response pattern may be related to study design (including dose selection), methodological limitations, or modulation of insulin processing and/or counter-regulatory responses. Oral HDV-I was generally safe and well tolerated with no incidence of hypoglycemic episodes or serious adverse events. The observed glucose lowering activity at very low doses of oral HDV-I suggests potential for improving glycemic control with less risk of the major proximal adverse effects of insulin therapy. However, results of long-term randomized controlled trials are required to achieve this potential.

Acknowledgments

This study was presented in part as a poster and published as an abstract at the 68th annual meeting of the American Diabetes Association, June 14-17, 2008, San Francisco, California, USA. The authors thankfully acknowledge G. Alexander Fleming, MD, president/CEO of Kinexum, for reviewing the article and for his constructive comments.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: AUC, area under the concentration-time curve; BMI, body mass index; FPG, fasting plasma glucose; GCP, good clinical practice; HbA1c, hemoglobin A1c; HDV-I, hepatic-directed vesicle-insulin; HTM, hepatocyte-targeting molecule; HTM-B, hepatocyte-targeting molecule-biotin phosphatidylethanolamine; ICH, International Conference on Harmonization; IV, intravenous; MAO, monoamine oxidase; MedDRA, medical dictionary for regulatory activities; OADs, oral antidiabetic drugs; OGTT, oral glucose tolerance test; PPG, postprandial plasma glucose; SD, standard deviation; U, unit; USP, United States Pharmacopeia.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared the following potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: W. Blair Geho, MD, PhD is a consultant to Diasome Pharmaceuticals, Inc. Len N. Rosenberg, PhD, RPh is an officer and shareholder of Diasome Pharmaceuticals, Inc. Sherwyn L. Schwartz, MD has no relevant conflict of interest to disclose. John R. Lau, BS is a consultant to and shareholder of Diasome Pharmaceuticals, Inc. Theophilus J. Gana, MD, PhD is a clinical consultant to Diasome Pharmaceuticals, Inc.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This study was funded by Diasome Pharmaceuticals, Inc.

References

- 1. UK Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS) Group. Intensive blood-glucose control with sulphonylureas or insulin compared with conventional treatment and risk of complications in patients with type 2 diabetes (UKPDS 33). Lancet. 1998;352(9131):837-853. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ohkubo Y, Kishikawa H, Araki E, et al. Intensive insulin therapy prevents the progression of diabetic microvascular complications in Japanese patients with non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus: a randomized prospective 6-year study. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 1995;28(2):103-117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Turner RC, Cull CA, Frighi V, Holman RR. Glycemic control with diet, sulfonylurea, metformin, or insulin in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: progressive requirement for multiple therapies (UKPDS 49). UK Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS) Group. JAMA. 1999;281(21):2005-2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Wright A, Burden AC, Paisey RB, Cull CA, Holman RR; U.K. Prospective Diabetes Study Group. Sulfonylurea inadequacy: efficacy of addition of insulin over 6 years in patients with type 2 diabetes in the U.K. Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS 57). Diabetes Care. 2002;25(2):330-336. [Erratum in: Diabetes Care. 2002;25(7):1268.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hunt LM, Valenzuela MA, Pugh JA. NIDDM patients’ fears and hopes about insulin therapy. The basis of patient reluctance. Diabetes Care. 1997;20(3):292-298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Korytkowski M. When oral agents fail: practical barriers to starting insulin. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2002;26(suppl 3):S18-S24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Peyrot M, Rubin RR, Lauritzen T, et al. The International DAWN Advisory Panel. Resistance to insulin therapy among patients and providers: results of the cross-national Diabetes Attitudes, Wishes, and Needs (DAWN) study. Diabetes Care. 2005;28(11):2673-2679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Heinemann L, Pfützner A, Heise T. Alternative routes of administration as an approach to improve insulin therapy: update on dermal, oral, nasal and pulmonary insulin delivery. Curr Pharm Des. 2001;7(14):1327-1351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Owens DR, Zinman B, Bolli G. Alternative routes of insulin delivery. Diabetes Med. 2003;20(11):886-898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Arbit E, Kidron M. Oral Insulin: the rationale for this approach and current development. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2009;3(3):562-567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Heinemann L, Jacques Y. Oral insulin and buccal insulin: a critical reappraisal. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2009;3(3):568-584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Geho WB, Geho HC, Lau J, Gana TJ. Hepatic-directed vesicle insulin: a review of formulation development and preclinical evaluation. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2009;3(6):1451-1459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Davis SN, Geho B, Tate D, Galassetti P, Lau J, Granner D, Mann S. The effects of HDV-insulin on carbohydrate metabolism in Type 1 diabetic patients. J Diabetes Complications. 2001;15(5):227-233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Geho B, Lau J, Rosenberg L. Hepatic-directed vesicle-insulin: evaluation of a novel oral and subcutaneous insulin delivery system in animal models of diabetes (Abstract). Diabetes. 2008;57(suppl 1):A126. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Schwartz S, Geho B, Rosenberg L, Lau J. A 2-week randomized, active comparator study of two HDV-Insulin routes (SC and oral) and SC human insulin in patients with type 1 diabetes mellitus (Abstract). Diabetes. 2008;57(suppl 1):A124. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Blackard WG, Nelson NC. Portal and peripheral vein immunoreactive insulin concentrations before and after glucose infusion. Diabetes. 1970;19(5):302-306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ferrannini E, Wahren J, Faber OK, Felig P, Binder C, DeFronzo RA. Splanchnic and renal metabolism of insulin in human subjects: a dose-response study. Am J Physiol. 1983;244(6):E517-E527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Meier JJ, Veldhuis JD, Butler PC. Pulsatile insulin secretion dictates systemic insulin delivery by regulating hepatic insulin extraction in humans. Diabetes. 2005;54(6):1649-1656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Horwitz DL, Starr JI, Mako ME, Blackard WG, Rubenstein AH. Proinsulin, insulin, and C-peptide concentrations in human portal and peripheral blood. J Clin Invest. 1975;55(6):1278-1283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Garvey WT, Olefsky JM, Griffin J, Hamman RF, Kolterman OG. The effect of insulin treatment on insulin secretion and insulin action in type II diabetes mellitus. Diabetes. 1985;34(3):222-234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Shishko PI, Kovalev PA, Goncharov VG, Zajarny IU. Comparison of peripheral and portal (via the umbilical vein) routes of insulin infusion in IDDM patients. Diabetes. 1992;41(9):1042-1049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Henry RR. Glucose control and insulin resistance in non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. Ann Intern Med. 1996;124(1 pt 2):97-103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. DeFronzo RA, Simonson D, Ferrannini E. Hepatic and peripheral insulin resistance: a common feature of type 2 (non-insulin-dependent) and type 1 (insulin-dependent) diabetes mellitus. Diabetologia. 1982;23(4):313-319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Reaven GM. Banting lecture 1988. Role of insulin resistance in human disease. Diabetes. 1988;37(12):1595-1607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ruige JB, Assendelft WJ, Dekker JM, Kostense PJ, Heine RJ, Bouter LM. Insulin and risk of cardiovascular disease: a meta-analysis. Circulation. 1998;97(10):996-1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Giovannucci E. Insulin, insulin-like growth factors and colon cancer: a review of the evidence. J Nutr. 2001;131(suppl 11):S3109-S3120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Geho B, Lau J, Rosenberg L, Schwartz S. A single-blind, placebo-controlled, food-dose timing trial of oral HDV-Insulin in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetes. 2009;58(suppl 1):A112. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Field JB. Insulin extraction by the liver. Ann Rev Med. 1973;24:309-314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Eaton RP, Allen RC, Schade DS. Hepatic removal of insulin in normal man: dose response to endogenous insulin secretion. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1983;56(6):1294-1300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Bratusch-Marrain PR, Waldhäusl WK, Gasić S, Hofer A. Hepatic disposal of biosynthetic human insulin and porcine C-peptide in humans. Metabolism. 1984;33(2):151-157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]