Abstract

The incidence of insulinopenic diabetes mellitus is constantly increasing, and in addition, approximately a third of all hyperinsulinemic diabetic patients develop insulinopenia. Optimal glycemic control is essential to minimize the risk for diabetes-induced complications, but the majority of diabetic patients fail to achieve proper long-term glucose levels even in clinical trials, and even more so in clinical practice. Compliance with a treatment regimen is likely to be higher if the procedure is simple, painless, and discreet. Thus, insulin has been suggested for nasal, gastrointestinal, and inhalation therapy, but so far with considerable downsides in effect, side effects, or patient acceptance. The stratum corneum is the main barrier preventing convenient drug administration without the drawbacks of subcutaneous injections. Recently, devices with miniaturized needles have been developed that combine the simplicity and discretion of patch-based treatments, but with the potential of peptide and protein administration. As this review describes, initial comparisons with subcutaneous administration now suggest microneedle patches for active insulin delivery are efficient in maintaining glycemic control. Hollow microneedle technology could also prove to be efficient in systemic as well as local delivery of other macromolecular drugs, such as vaccines.

Keywords: microneedles, diabetes, insulin, intradermal, transdermal, hollow

Diabetes Mellitus and Insulin Treatment

Insulin deficiency is the hallmark of diabetes mellitus (DM) type 1 and plays an important role in type 2 DM. Before the discovery of insulin, type 1 DM was a uniformly mortal disease, but even with today’s plethora of insulin delivery systems, such as insulin pumps, short and long-acting insulin analogues, and transplantation of islets of Langerhans, or whole pancreas, DM still causes to significant morbidity and mortality. The most important risk factor for complications is poor control of blood glucose.1-4 At the same time, strict glycemic control is associated with a markedly greater risk of hypoglycemia,3,5,6 and recent systematic reviews have not been able to show any improvement in all cause mortality.5,6 However, even adequate glycemic control is difficult to achieve for a large number of patients.7 This can be traced to difficult to regulate disease in some patients, but in the majority it is tied to poor adherence to insulin-treatment and glucose monitoring.

The problem is that multiple daily injections, and blood samples, which are painful and cause trauma to the skin makes it difficult for diabetic patients to adhere to an optimal treatment regimen. It is known that the majority of diabetic patients are not confident to manage their disease themselves,8 and that 1 out of 5 diabetic children place their injections inappropriately.9 Every fourth diabetes patient treated with insulin describes some anxiety regarding self-injection.8,10 Furthermore, the perceived risk of hypoglycemia is another important factor that reduces adherence to strict glucose control.11

Injections are necessary since the oral bioavailability of insulin is poor because it is poorly absorbed and quickly degraded in the gastrointestinal tract. In addition, as a protein insulin do not permeate the skin without enhancement strategies. An alternative to daily injections is the subcutaneous insulin pump which has been shown to achieve glycemic control, and reduce the risk of complications in diabetic patients.1 On the other hand, insulin pump therapy requires bulky equipment and the insertion of the subcutaneous catheter, which may be painful.

Compliance with a treatment regimen is likely to be higher if the procedure is simple, painless, and discrete.12 Insulin has so far been suggested for nasal, gastrointestinal, as well as inhalation therapy.10,13 Gastrointestinal and nasal administrations have been unsuccessful so far, but an insulin inhaler was recently developed and approved.14 However, since insulin is a potent growth factor, there is concern that intra-alveolar deposition of insulin could impair pulmonary function,15,16 and adoption has been slow. Other routes are therefore to prefer, which do not compromise the comfort and future health of diabetic patients. This review aims to discuss recent research on microneedle drug administration through the skin barrier.

The Skin and Drug Delivery

The skin has 2 main functions: It is a physical barrier, and a receiver of external stimuli such as pain. The skin consists of 3 main sections; the epidermis, dermis, and hypodermis, or subcutaneous tissue (Figure 1). The outer part, epidermis, is approximately 100 µm thick and consists of a main barrier part, stratum corneum, where stacked, dead cells are continuously replaced by outward moving, new cells produced in the more basal layer. The underlying dermis is more than 1000 µm thick and contains blood vessels, sweat glands, hair follicles, and nerves. The dermis, especially the inner dermis, is very rich in nociceptors. The subcutaneous tissue, finally, is a layer of adipose tissue serving as an energy reservoir and thermal insulation.17

Figure 1.

Schematic illustration depicting a cross section of the skin, with epidermis, dermis, and subcutaneous tissue.46

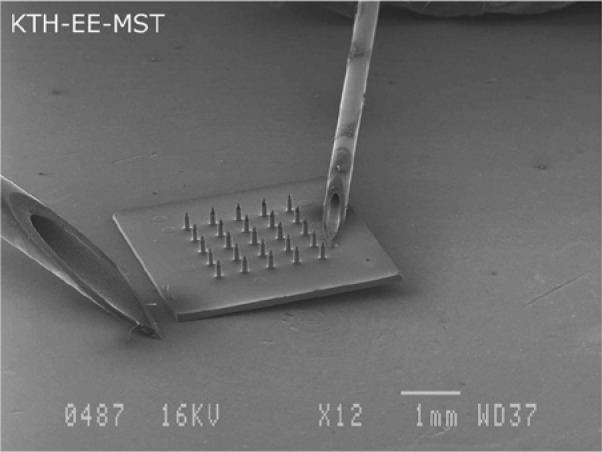

Transdermal drug delivery means that a pharmaceutical compound is moved across the skin for subsequent systemic distribution. For hydrophobic drugs that easily diffuse across the skin, patch-based drug delivery provides an excellent route of administration. The drawback of this approach for insulin is that the skin’s outer stratum corneum provides an insurmountable barrier. Micrometer-scale needles represent a unique technological approach to enhance drug permeation across the stratum corneum and thereby enable delivery of drugs that would normally require injection. Microneedles are usually designed to penetrate down to the dermal layer of skin, but without reaching and stimulating the dermal nerves. The needles are usually arranged in arrays (Figure 2) and can be used in several ways to enhance transdermal drug transport. The needles can be inserted into the skin before applying the drug in question, to create micron-sized pores that are big enough to increase permeability of macromolecules and even microparticles. Drugs may also be coated onto the microneedles and administrated by inserting the needles into the skin, and there are even reports of polymer microneedles that dissolve upon application.18 Hollow microneedles, however, are used to directly inject dissolved drug into the skin (Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Scanning electron microscopy picture showing a complete microneedle device displayed next to 2 standard 20 G and 27 G syringes.35

Figure 3.

Photomicrograph showing a pattern in the skin of a human subject after dye injection through the patch-like microneedle device.28

Microneedle Technology

In 1998, the Prausnitz Lab at Georgia Institute of Technology reported the fabrication and insertion of microneedles long enough to cross the stratum corneum, but short enough to not stimulate most nociceptors, which makes the technology minimally invasive and painless.19,20 Their report for the first time describes the use of microfabricated microneedles to enhance drug delivery across skin.21 In 2003, the same lab reported novel microfabrication techniques for solid and hollow microneedle arrays in the micrometer scale made from silicon, metal, as well as biodegradable polymer,20 and that same year, Griss et al published the first side-opened hollow out-of-wafer-plane silicon microneedles.22 In 2005, hollow microneedles were proven to be are clinically effective in bypassing the stratum corneum for drug injections,23 and later, Kim et al fabricated out-of-plane hollow silicon dioxide microneedle arrays and investigated stratum corneum and skin insertion by altering needle width and cross-section.24 Recently, several research groups have developed devices with miniaturized needles that combines the simplicity and discretion of patch-based treatments with the potential of peptide and protein administration.24-28 The perhaps most promising drug delivery devices are achieved with a technique known as a Micro-Electro-Mechanical System (MEMS). MEMS is microfabrication technology integrating mechanical elements with sensors, actuators, and electronics on a silicon substrate, rendering possible the production of complete systems-on-a-chip that could completely control insulin treatment (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Schematic overview of a Micro-Electro-Mechanical System (MEMS) device.

The main advantage of the parenteral approach is that the drug is introduced into the body without being passed through the human body’s various defense systems. The length of the microneedles means that they reach the capillary-rich layers of the skin where insulin can be readily absorbed and distributed via the circulation. If sufficient bioavailability can be obtained using this technique it would have the advantages of subcutaneous drug delivery, but in a discreet, painless, and minimally invasive manner.

Initial studies on microneedle devices revealed that the needles can be inserted into the skin in a predictable manner.29 The first reports of enhanced transdermal delivery of insulin in vivo regarded the use of solid microneedles for increasing insulin delivery and decreasing blood glucose levels.30 Later, infusion in vivo and into human cadaver skin also showed promising results.31,32 In all studies, the human subjects describe microneedle insertions as painless19,20 and in a recent study, all tested microneedles were described as significantly less painful than a 26-gauge hypodermic needle.33

In 2003, McAllister et al demonstrated microliter infusion into skin in vivo using hollow microneedles, including microinjection of insulin to reduce blood glucose levels in diabetic rats.20 Since then, several groups have tested microneedle devices for insulin delivery and demonstrated insulin infusion as well as effective reduction of blood glucose concentrations in diabetic rats.30,34,35 Studies so far show no disadvantage using transdermal patches as compared to subcutaneous injection. Subcutaneous injections are known to cause a substantial variability in dose delivered,11 and intradermal delivery may achieve a more controlled distribution with lower variability. Recently the use of active microneedle delivery was shown to be effective in conscious, chronically diabetic animals,35 which is important since earlier studies were mostly in short time diabetes without diabetes induced skin changes,36 and some studies have been performed on anaesthetized rats with minimal physiological registration.34

Intradermal Glucose Monitoring

Perhaps even more painful than hypodermic insulin injections are the lancets used for conventional blood collection for blood glucose monitoring.37 However, 0.2 µl is sufficient monitor blood glucose, indicating that the microneedle approach is a feasible alternative.37 In MEMS technology, sensors can be incorporated into a system to gather information from the environment through measurements of, for example, mechanical, biological, or chemical phenomena. The electronics then process the obtained information and direct the actuators to respond by increasing or decreasing the infusion rate. Thus, it should be possible to develop devices with incorporated blood glucose sensing and self-controlled insulin rates. In 2000, Smart et al described painless blood glucose testing with a silicon microneedle device, drawing less than 0.2 microliters of blood into a microcuvette, where an assay was performed automatically.38 In 2005, Wang et al demonstrated the use of microneedles for extraction of dermal interstitial fluid for glucose monitoring.39,40 The team reported that the glucose concentrations measured in the interstitial fluid correlated well with blood glucose concentrations measured on rat tail vein blood and on human subjects with a conventional lancet method. Were these studies to be followed up, such a sensor could be integrated with the insulin device to further improve diabetes management.

Concluding Remarks

Recent research shows that the newly developed microneedles are a plausible treatment strategy for insulin delivery to diabetes patients. Further studies should aim at investigating the microneedle devices in terms of adjusted flow rate and biocompatibility. Recent research presents the microneedles are also good candidates for controllable and patient-friendly insulin delivery. The clinical and preclinical data set the stage for microneedle arrays used as intradermal patches in clinical practice and might introduce a more efficient treatment for diabetic patients. This microneedle technology could also prove to be efficient in systemic as well as local delivery of other macromolecular medications, skin-impermeant drugs and biopharmaceuticals, such as protein and DNA vaccines, and endocrine substances.41-45

In parallel with avoiding multiple injection regimens, needle anxiety, and social difficulties associated with self-injecting, microneedle administration route requires minimal training and attention. It is not at all unlikely that compliance with insulin treatment would be higher if the treatment procedure was simple and painless, as with patch-like microneedle devices. Thus, microneedles are a feasible option to improve glycemic control, could set the stage for improved and more comfortable diabetes management and reduce the risk of long-term diabetes complications.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: DM, diabetes mellitus; MEMS, micro-electro-mechanical system.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This article was funded by the Swedish Society for Medical Research.

Reference

- 1. The effect of intensive treatment of diabetes on the development and progression of long-term complications in insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. The Diabetes Control and Complications Trial Research Group. N Engl J Med. 1993;329(14):977-986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Eeg-Olofsson K, Cederholm J, Nilsson PM, et al. Glycemic control and cardiovascular disease in 7,454 patients with type 1 diabetes: an observational study from the Swedish National Diabetes Register (NDR). Diabetes Care. 2010;33(7):1640-1646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Callaghan BC, Little AA, Feldman EL, Hughes RA. Enhanced glucose control for preventing and treating diabetic neuropathy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;6:CD007543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ray KK, Seshasai SR, Wijesuriya S, et al. Effect of intensive control of glucose on cardiovascular outcomes and death in patients with diabetes mellitus: a meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Lancet. 2009;373(9677):1765-1772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Boussageon R, Bejan-Angoulvant T, Saadatian-Elahi M, et al. Effect of intensive glucose lowering treatment on all cause mortality, cardiovascular death, and microvascular events in type 2 diabetes: meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. BMJ. 2011;343:d4169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hemmingsen B, Lund SS, Gluud C, et al. Intensive glycaemic control for patients with type 2 diabetes: systematic review with meta-analysis and trial sequential analysis of randomised clinical trials. BMJ. 2011;343:d6898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ali MK, Bullard KM, Saaddine JB, Cowie CC, Imperatore G, Gregg EW. Achievement of goals in U.S. diabetes care, 1999-2010. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(17):1613-1624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Korytkowski M, Niskanen L, Asakura T. FlexPen: addressing issues of confidence and convenience in insulin delivery. Clin Ther. 2005;27(suppl B):S89-S100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Birkebaek NH, Johansen A, Solvig J. Cutis/subcutis thickness at insulin injection sites and localization of simulated insulin boluses in children with type 1 diabetes mellitus: need for individualization of injection technique? Diabet Med. 1998;15(11):965-971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Owens DR, Zinman B, Bolli G. Alternative routes of insulin delivery. Diabet Med. 2003;20(11):886-898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Davies M. The reality of glycaemic control in insulin treated diabetes: defining the clinical challenges. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2004;28(suppl 2):S14-S22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Korytkowski M, Bell D, Jacobsen C, Suwannasari R. A multicenter, randomized, open-label, comparative, two-period crossover trial of preference, efficacy, and safety profiles of a prefilled, disposable pen and conventional vial/syringe for insulin injection in patients with type 1 or 2 diabetes mellitus. Clin Ther. 2003;25(11):2836-2848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Barnett AH. Exubera inhaled insulin: a review. Int J Clin Pract. 2004;58(4):394-401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. White S, Bennett DB, Cheu S, et al. EXUBERA: pharmaceutical development of a novel product for pulmonary delivery of insulin. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2005;7(6):896-906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Woods TC, Zhang B, Mercogliano F, Dinh SM. Response of the lung to pulmonary insulin dosing in the rat model and effects of changes in formulation. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2005;7(3):516-524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Mandal TK. Inhaled insulin for diabetes mellitus. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2005;62(13):1359-1364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Norlén. The Skin Barrier—Structure and Physical Function. Stockholm, Sweden: Department of Medical Biochemistry and Biophysics, Karolinska Institute; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Park J, Bungay PM, Lutz RJ, et al. Evaluation of coupled convective-diffusive transport of drugs administered by intravitreal injection and controlled release implant. J Control Release. 2005;105(3):279-295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kaushik S, Hord AH, Denson DD, et al. Lack of pain associated with microfabricated microneedles. Anesth Analg. 2001;92(2):502-504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. McAllister DV, Wang PM, Davis SP, et al. Microfabricated needles for transdermal delivery of macromolecules and nanoparticles: fabrication methods and transport studies. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100(24):13755-13760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Henry S, McAllister DV, Allen MG, Prausnitz MR. Microfabricated microneedles: a novel approach to transdermal drug delivery. J Pharm Sci. 1998;87(8):922-925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Griss P, Stemme G. Side-opened out-of-plane microneedles for microfluidic transdermal liquid transfer. J Microelectromechanical Syst. 2003;12(3):296-301. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Sivamani RK, Stoeber B, Wu GC, Zhai H, Liepmann D, Maibach H. Clinical microneedle injection of methyl nicotinate: stratum corneum penetration. Skin Res Technol. 2005;11(2):152-156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kim S, Shetty S, Price D, Bhansali S. Skin penetration of silicon dioxide microneedle arrays. Conf Proc IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc. 2006;1:4088-4091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Roxhed N, Samel B, Nordquist L, Griss P, Stemme G. Painless drug delivery through microneedle-based transdermal patches featuring active infusion. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng. 2008;55:1063-1071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Roxhed N, Griss P, Stemme G. Reliable in-vivo penetration and transdermal injection using ultra-sharp hollow microneedles. Paper presented at: IEEE International Conference on Solid State Sensors, Actuators, and Microsystems (Transducers); 2005; Seoul, Korea. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Roxhed N, Samel B, Nordquist L, Griss P, Stemme G. Compact, seamless integration of active dosing and actuation with microneedles for transdermal drug delivery. Paper presented at: IEEE International Conference on Micro Electro Mechanical Systems; 2006; Istanbul, Turkey. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Roxhed N. A Fully Integrated Microneedle-based Transdermal Drug Delivery System. Stockholm, Sweden: Microsystem Technology Laboratory, School of Electrical Engineering, Royal Institute of Technology; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Davis SP, Landis BJ, Adams ZH, Allen MG, Prausnitz MR. Insertion of microneedles into skin: measurement and prediction of insertion force and needle fracture force. J Biomech. 2004;37(8):1155-1163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Martanto W, Davis SP, Holiday NR, Wang J, Gill HS, Prausnitz MR. Transdermal delivery of insulin using microneedles in vivo. Pharm Res. 2004;21(6):947-952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Martanto W, Moore JS, Kashlan O, et al. Microinfusion using hollow microneedles. Pharm Res. 2006;23(1):104-113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Wang PM, Cornwell M, Hill J, Prausnitz MR. Precise microinjection into skin using hollow microneedles. J Invest Dermatol. 2006;126(5):1080-1087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Gill HS, Denson DD, Burris BA, Prausnitz MR. Effect of microneedle design on pain in human volunteers. Clin J Pain. 2008;24(7):585-594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Davis SP, Martanto W, Allen MG, Prausnitz MR. Hollow metal microneedles for insulin delivery to diabetic rats. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng. 2005;52(5):909-915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Nordquist L, Roxhed N, Griss P, Stemme G. Novel microneedle patches for active insulin delivery are efficient in maintaining glycaemic control: an initial comparison with subcutaneous administration. Pharm Res. 2007;24:1381-1388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Meurer M, Stumvoll M, Szeimies RM. [Skin changes in diabetes mellitus]. Hautarzt. 2004;55(5):428-435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Nakayama T, Kudo H, Sakamoto S, Tanaka A, Mano Y. Painless self-monitoring of blood glucose at finger sites. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes. 2008;116(4):193-197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Smart WH, Subramanian K. The use of silicon microfabrication technology in painless blood glucose monitoring. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2000;2(4):549-559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Mukerjee EV, Collins SD, Isseroff RR, Smith RL. Microneedle array for transdermal biological fluid extraction and in situ analysis. Sensors Actuators. 2004;114:267-275. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Wang PM, Cornwell M, Prausnitz MR. Minimally invasive extraction of dermal interstitial fluid for glucose monitoring using microneedles. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2005;7(1):131-141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Matriano JA, Cormier M, Johnson J, et al. Macroflux microprojection array patch technology: a new and efficient approach for intracutaneous immunization. Pharm Res. 2002;19(1):63-70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Lin W, Cormier M, Samiee A, et al. Transdermal delivery of antisense oligonucleotides with microprojection patch (Macroflux) technology. Pharm Res. 2001;18(12):1789-1793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Coulman SA, Barrow D, Anstey A, et al. Minimally invasive cutaneous delivery of macromolecules and plasmid DNA via microneedles. Curr Drug Deliv. 2006;3(1):65-75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Mikszta JA, Alarcon JB, Brittingham JM, Sutter DE, Pettis RJ, Harvey NG. Improved genetic immunization via micromechanical disruption of skin-barrier function and targeted epidermal delivery. Nat Med. 2002;8(4):415-419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Cormier M, Johnson B, Ameri M, et al. Transdermal delivery of desmopressin using a coated microneedle array patch system. J Control Release. 2004;97(3):503-511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Dawkins R, Kerrod R. Cross section of human skin. In: The Oxford Illustrated Science Encyclopedia. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]