Abstract

Objectives. I examined the frequency and developmental timing of traumatic loss resulting from the health disparity of homicide among young Black men in Baltimore, Maryland.

Methods. Using a modified grounded theory approach, I conducted in-depth semistructured interviews with 40 Black men (aged 18–24 years) from January 2012 to June 2013. I also constructed adapted life history calendar tools using chronologies of loss, and (1) provided a comprehensive history of loss, (2) determined a specific frequency of homicide deaths, (3) indicated participants’ relationship to the decedents, and (4) identified the developmental timing of deaths.

Results. On average, participants knew 3 homicide victims who were overwhelmingly peers. Participant experiences of homicide death started in early childhood, peaked in adolescence, and persisted into emerging adulthood. The traumatic loss of peer homicide was a significant developmental turning point and disrupted participants’ social networks.

Conclusions. The traumatic loss of peer homicide was a prevalent life course experience for young Black men and identified the need for trauma- and grief-informed interventions. Future research is needed to examine the physical and psychosocial consequences, coping resources and strategies, and developmental implications of traumatic loss for young Black men in urban contexts.

The epidemic of homicide among Black males in the United States has been named “a new American tragedy.”1 Despite historic national declines in homicide deaths,2 homicide remains the leading cause of death for Black youths aged 10 to 24 years.3 Homicide disproportionately affects Black males in this age group, with the homicide rate for Black males (51.5 per 100 000) exceeding rates for their Hispanic (13.5 per 100 000) and White (2.9 per 100 000) male peers.3 However, these statistics narrowly articulate the magnitude of this disparity in the lives of Black boys and men. In addition to premature death, homicide places Black males at disproportionate risk for experiencing the traumatic loss of a peer and becoming homicide survivors. Homicide survivors are the friends, family, and community members of homicide victims who face the task of living on after a loved one is murdered.4–7 The sudden, violent, and preventable nature of homicide deaths distinguishes these losses as traumatic for survivors8 and can produce adverse health consequences and complicate grief.9–13 Despite our documented awareness of the overrepresentation of Black males among homicide victims, the unequal burden of traumatic loss experienced by young Black men as survivors remains understudied. My study addressed this gap by examining the life course frequency and developmental timing of traumatic loss resulting from the health disparity of homicide among a sample of young Black men (aged 18–24 years) in Baltimore, Maryland.

Studies suggest that Blacks experience a higher likelihood of surviving a homicide death than any other racial/ethnic group,9,13,14 and this is partly explained by location in context.15,16 Blacks are more likely than are Whites to reside in neighborhoods of concentrated disadvantage where the incidence of homicide is higher.17–23 Between 2010 and 2013, Baltimore experienced 873 homicides, of which 738 victims (85%) were Black males and 27 victims (3%) were White males.24 This geographic concentration of disadvantage and violence increases the likelihood that Black males living in these neighborhoods will experience the traumatic loss of 1 or more homicide victims within their social networks. However, existing research has failed to capture the frequency at which the lives of Blacks are buffeted by the traumatic loss of homicide.6 The lived experiences of Black males as homicide survivors have been almost entirely overlooked.25

For Black males growing up in contexts of long-term risk, how often (frequency) and when (developmental timing) the traumatic loss of homicide occurs across the life course may produce varying developmental implications.15,16,26,27 The nascent body of literature examining homicide survivorship has documented adverse mental and behavioral health consequences for survivors, including posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD),9 anxiety and depression,11 traumatic and complicated grief,5,10,28 substance abuse,13 emotional reactivity,12 and a hindered ability to function.12 However, the existing research on homicide survivorship has largely approached the study of this phenomenon as a dichotomous experience, asking participants to report whether they have survived a homicide death.9–13 These studies failed to capture a multiplicity of homicide deaths and its potential consequences for survivors. Health outcomes may be worse for young Black men situated in economically disadvantaged contexts, who are at higher risk for surviving multiple homicide deaths across the life course.15,26,27

The developmental timing (e.g., early childhood [0–5 years], school age [6–12 years], adolescence [13–17 years], and emerging adulthood [18–24 years]) of traumatic loss can also contribute to the health and well-being of Black male homicide survivors.14,26 From a life course perspective,29,30 life events that happen before or after established developmental norms are considered off-time and pose implications for subsequent development.15,26,27 Consequently, the timing of homicide deaths along the developmental trajectories of survivors can shape their cognitive, emotional, and behavioral resources, responses, and outcomes.26,28–30 However, this area of research remains largely unexplored.6 In their review of the literature on homicide survivorship, Hertz et al.6 noted that until research investigates the nature, extent, and developmental context of homicide deaths among the surviving family and friends of homicide victims, the health care system will be limited in both its understanding of the impact of homicide survivorship and its ability to respond appropriately to the needs of survivors. By using a life course perspective29,30 and qualitative31,32 and adapted life history calendar (LHC) methods,33,34 I examined the frequency, multiplicity, and developmental timing of traumatic loss resulting from homicide in the lives of young Black men in Baltimore.

METHODS

I gathered the data for this study from a larger qualitative project that explored the process, context, and meaning of traumatic loss and homicide survivorship among young Black men during the transition to adulthood.35 These data were collected over the course of 18 months (January 2012–June 2013), using ethnographic methods (participant observation and field notes), in-depth interviews, and adapted life history calendar techniques34 at the Striving for Upward Progress (SUP) youth development program (pseudonym) in Baltimore. SUP is a large general equivalency diploma and job-readiness training program that serves low-income youths and young adults (age 16–25 years) who are disconnected from the school system (e.g., dropout or dismissal). For more than a decade, SUP has provided education, employment, mental health, and wraparound services to support educational and employment success for Baltimore youths. SUP is situated in a highly segregated and economically disadvantaged east Baltimore neighborhood where 89.5% of residents are Black, the unemployment rate is 23.6%, and 49.2% of family households live below the poverty line.36

I recruited a sample of 40 young Black men aged 18 to 24 years to participate in the study. The average participant was 20 years old. Of the 40 participants, 10 achieved their high school diplomas and were engaged with SUP for job training and assistance. The remaining 30 young men were primarily engaged with SUP for general equivalency diploma instruction. There was great flux in young men’s employment status over the course of the study. At the time of participant interviews, nearly one half of the sample (n = 16) was employed full- or part-time. More than half (58%) of the participants mentioned some contact with the criminal justice system as a result of arrest or incarceration, and nearly all participants had some contact with police as a result of a random stop and search in their Baltimore neighborhoods. Eleven young men were fathers, and 3 were expectant fathers.

Procedure

A certificate of confidentiality was issued by the Department of Health and Human Services to protect sensitive participant data concerning violence and homicide death. All participants were informed of the certificate of confidentiality at the time they consented to participate in the study. SUP program members who self-identified as Black, male, 18 to 24 years of age, and reported experiencing a homicide-related death were eligible to participate.

As a licensed mental health practitioner, I collaborated with SUP clinicians to develop and facilitate a weekly loss and grief group in the center. This psychoeducational and support group offered a safe space where the young men and women of SUP voluntarily participated, shared experiences of loss, and processed grief. The group also provided me with a role in the community program through which relationship building, participant observation, and recruitment occurred over the course of 18 months. Engagement in broader center activities (e.g., town hall meetings, open microphone performances, basketball games, etc.) also provided opportunities for informal interactions that helped build trusting relationships with program staff and participants. This prolonged engagement provided broader exposure to young men’s lives and the ecological contexts in which their specific experiences of violence, trauma, and loss were situated. I took extensive field notes,37 and these were transcribed and managed in ATLAS.ti (ATLAS.ti, Corvallis, OR).

As a participant observer in the loss and grief group, young men’s discussions of traumatic loss and community violence positioned me to recruit research participants who were “information rich.”38 In-depth interviews were conducted with young men in private, confidential spaces at the program site using a semistructured interview technique.32 The goal of these interviews was to gain a rich understanding of the process, context, and meaning of traumatic loss and homicide survivorship among young Black men. Interviews lasted an average of 2 hours (range = 1.5–4 hours). Young men received a $20 incentive for their participation. Each participant self-selected or was assigned a pseudonym, as were the decedents. All interviews were digitally recorded, transcribed verbatim, managed, and coded in ATLAS.ti. I used a modified grounded theory approach, including the technique of constant comparison,31 to guide the data analyses of the interview transcripts.

During each interview, participants constructed chronologies of loss. Borrowing from LHC techniques,33,34 this technique was a tool for young men to record their experiences of loss over time. Recalling the exact timing of life events could be a challenge for study participants.33 Chronologies of loss served as a visual cue that helped young men recall the timing and sequencing of homicides deaths across the life course.34 Chronologies simultaneously enhanced the trustworthiness of the data.39 I compared the young men’s interviews with their chronologies of loss to cross reference the number, timing, and sequencing of deaths. When first and last names of homicide victims were disclosed, I compared these reports with local news periodicals that contained records of Baltimore homicides.24 In this way, chronologies of loss enhanced the credibility and dependability of the data by providing a tool that triangulated data sources and methods.39

This tool also provided me with a rigorous, systematic approach to understanding traumatic loss over time. To construct chronologies, participants were given a blank sheet of paper and writing utensils, and instructed to draw a line from one end of the paper to the other. The beginning of the each timeline represented the date of each participant’s birth and the end of the line represented the date of the interview. Participants were directed to mark the years in their lives where they experienced a death-related loss and were instructed to write the name and relationship to the decedent (e.g., Willie, friend). After all deaths were recorded on the chronology, participants were asked to visually identify (e.g., circle) each death that resulted from homicide. Each constructed chronology

provided a comprehensive history of loss,

specified the cause of death,

determined a specific frequency of homicide deaths,

indicated participants’ relationship to decedents (e.g., brother, cousin, father, friend, etc.), and

identified the developmental timing of deaths (Figure 1).

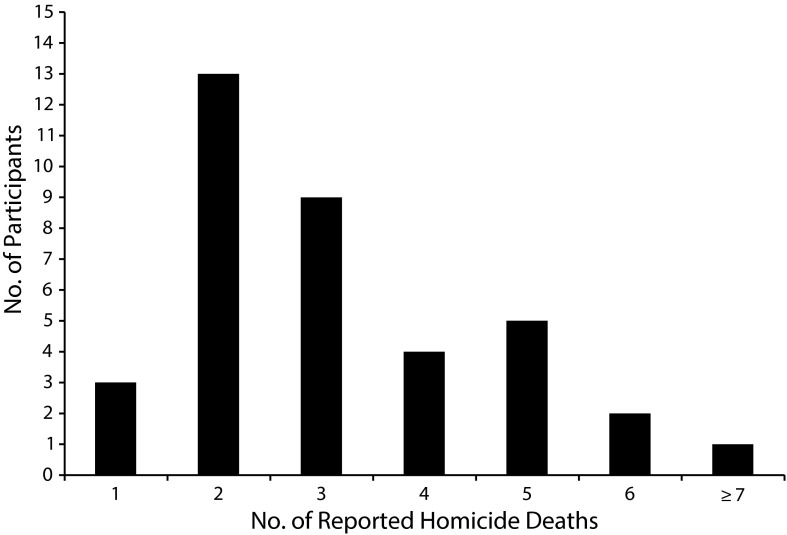

FIGURE 1—

Sample chronology of loss: DeOnte (age 20 years).

Note. The horizontal line indicates the timeline of losses DeOnte experienced across his life course. The beginning of the line (far left) represents the year in which DeOnte was born (1992). The end of the line (far right) represents the year in which his interview occurred (2012). All of DeOnte’s experiences of death-related loss were a result of homicide.

Data Analyses

My findings were grounded in participant chronologies of loss that were analyzed to determine the frequency and developmental timing of traumatic loss resulting from homicide. I reviewed each participant’s chronology of loss, and I quantified these data by counting each death-related loss reported. I calculated the collective total of death-related losses for this sample (n = 40) by summing all deaths reported across participants. I subsequently determined a specific frequency of homicide deaths. This aggregate of homicide deaths was based on the reports of 37 participants (n = 37) in this sample. My research interviews revealed that 3 young men’s experiences of traumatic loss did not result from homicide (e.g., fatal asthma attack); therefore, they were excluded from all data analyses on homicide survivorship.

I also examined the developmental timing of homicide deaths for each participant and used these to identify patterning in the experience of homicide survivorship. Across participants, the sum total of homicide deaths reported during the developmental stages of early childhood, the school age years, adolescence, and emerging adulthood were determined based on participant reports of their ages when the homicide deaths of loved ones occurred. I paid specific attention to variations in the age at which young men reported experiencing their first traumatic loss as a result of homicide. Additional analyses focused on subsequent experiences of homicide deaths and developmental periods when high incidences of homicide deaths were reported across the sample. I included participants' quotes throughout the findings to give voice to young men’s lived experiences of the identified patterns in the LHC data. The related interview questions asked young men: (1) how many loved ones in your life have died as a result of neighborhood violence?, and (2) what is it like to have a loved one murdered? Together, these data provided critical insights about the frequency, timing, and multiplicity of homicide deaths experienced by young Black men across the life course.

RESULTS

Participant chronologies of loss indicated that frequent experiences of traumatic loss and homicide death began in early childhood and persisted through emerging adulthood for this group.

Frequency of Homicide Deaths

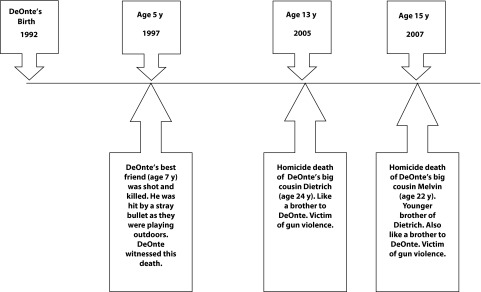

Across this sample of young Black men (n = 40), participants experienced a collective total of 267 deaths of peers, biological family members, and other important adults in their lives (e.g., church members). Of the 267 total deaths reported, 119 deaths (45%) resulted from homicide. This translated to an average of 3 homicide deaths per participant (n = 37; range = 1–10). Experiencing a singular homicide death was the exception for young Black men in this sample (n = 3). The majority of participants (n = 34) experienced 2 or more homicide deaths across the life course (Figure 2). Eleven participants reported witnessing 13 homicide deaths of loved ones, adding another layer of trauma to their experience as homicide survivors (Table 1).

FIGURE 2—

Number of study participants reporting a specific frequency of homicide deaths: Baltimore, MD.

TABLE 1—

Timing and Patterning of Homicide Death–Related Loss (119) Reported Across Developmental Stage and Age: Baltimore, MD

| Early Childhooda |

School Ageb |

Adolescencec |

Emergent Adulthoodd |

|||||||||||||||||||

| Variable | 0–3 Years | 4 Years | 5 Years | 6 Years | 7 Years | 8 Years | 9 Years | 10 Years | 11 Years | 12 Years | 13 Years | 14 Years | 15 Years | 16 Years | 17 Years | 18 Years | 19 Years | 20 Years | 21 Years | 22 Years | 23 Years | 24 Years |

| 1st HD | 1 | 1e | 1e | 1 | 1 | 4e | 4 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 4e | 3f | 4 | 2 | 2 | 1e | ||||||

| 2nd HD | 1 | 1e | 3 | 4 | 1 | 4e | 4f | 4e | 3 | 4 | 2 | 2e | 1 | |||||||||

| 3rd HD | 2 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 1 | ||||||||||||

| 4th HD | 1 | 2 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 3 | ||||||||||||||||

| 5th HD | 1 | 3 | 1 | 2 | ||||||||||||||||||

| 6th HD | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||

| 7th HD | 1 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 8th HD | 1 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 9th HD | 1 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 10th HD | 1 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| No. of HDs | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 9 | 12 | 12 | 18 | 11 | 10 | 12 | 3 | 10 | 1 | 1 |

Note. HD = homicide death.

There were a total of 2 HDs and 2 homicide survivors.

There were a total of 13 HDs and 11 homicide survivors.

There were a total of 56 HDs and 24 homicide survivors.

There were a total of 48 HDs and 26 homicide survivors.

One participant of the identified age group witnessed the homicide death reported.

Two participants of the identified age group witnessed the homicide death reported.

Of the 119 homicide deaths reported, males (109 decedents) and peers (105 decedents) were overrepresented among the homicide victims (Table 2). I conceptualized peers as persons in the same age group with whom participants shared a relationship (biological or social). The majority of peer homicide victims were socially related to participants (81%). A minority of peer victims were biological relatives (19%). Among this group of decedents, cousins were killed at the highest rates. Only 5 of the 105 reported peer homicide victims were female, and were not identified as romantic partners.

TABLE 2—

Relationship of Study Participants to Homicide Victims: Baltimore, MD

| Relation | No. |

| Peers (n = 105) | |

| Biological peers | |

| Brothers | 2 |

| Cousins | 18 |

| Social peers | |

| Male peers | 80 |

| Female peers | 5 |

| Nonpeers (n = 14) | |

| Paternal figures | |

| Fathers | 1 |

| Stepfathers | 1 |

| Grandfathers | 1 |

| Uncles | 5 |

| Maternal figures | |

| Mothers | 1 |

| Grandmothers | 1 |

| Aunts | 1 |

| Friends’ mothers | 2 |

| Other person: friend’s baby | 1 |

The frequency of peer homicides reported in the sample disrupted young men’s social relationships and altered the structure of their social networks. Niko (age 18 years), a 4-time homicide survivor shared the meaning of losing peers to neighborhood violence:

What does it mean to me? Well, it just makes me lose friends. I’m losing friends cause my friends is getting killed—some of my close friends—and then, it just, like, be nothing else left. If I ain’t got no friends then like what I’m supposed to do? I just sit in the house now. It’s no friends that I have.

For young Black men growing up in east Baltimore, the stability of their peer networks is threatened by the chronicity of neighborhood violence and the prevalence of traumatic loss among their social networks.

Timing, Multiplicity, and Patterning of Homicide Deaths

After I determined the specific frequency of homicide deaths in the sample, I examined the developmental timing of these deaths. My analyses found variations in the timing and patterning of participants’ experiences of homicide deaths along the life course. Chronologies indicated that participants’ initial experiences of traumatic loss resulting from homicide were represented across each developmental stage. A minority of young men experienced their first homicide death in early childhood (n = 2), with the earliest age of survivorship being 4 years old. An increasing number of participants survived their first homicide death in the school-age years (n = 11), and nearly half of the participants (n = 15) survived their first homicide death in adolescence. The remaining participants (n = 9) experienced their first homicide death in emerging adulthood.

Ricky’s (age 20 years) first experience of homicide death occurred at 12 years when his best friend (age 11 years) was murdered. Ricky described this traumatic loss as a key turning point that adversely affected his well-being, accelerated his life course, and altered his worldview:

It changed a lot of things. I just started caring less about childhood stuff. You know, like playing football and all that. It made me grow up a little faster too—watch for stuff I’m not even suppose to be watching out for like stray bullets and all types of stuff when no child should be worrying about stuff like that, you know? Shouldn’t nobody be worried about that. But at a young age, it made me start looking and open my eyes more and watch my surroundings and stuff. It messed me up. Even though I knew about people getting killed and stuff it still, it didn’t click with me yet. [His murder] messed me up. . . . No more playin’ football. No more ridin’ bikes and stuff and all of that. . . . You know, just little child stuff. I didn’t care too much about that.

The homicide deaths of close peers crystallized the lethality of neighborhood violence and created a sense of personal vulnerability to violent death among participants. At 12 years, this precocious knowledge changed Ricky’s perception of his developmental priorities, shifting his focus from sports and play to safety and survival.

The number of participants experiencing a traumatic loss increased over time, as did the number of homicide deaths reported per participant (Table 1). During the school-age years, reports of multiple homicide deaths emerged in the data, with 2 participants surviving a second traumatic loss at ages 10 and 12 years. During adolescence, the number of homicide deaths reported by participants increased steadily by age. Between the ages of 13 and 17 years, 24 participants reported 56 homicide deaths. More than one-half of these 24 homicide survivors (71%) reported experiencing multiple homicide deaths during this period.

Young men also experienced a clustering of homicide deaths during adolescence, with a rapid sequencing of homicide deaths happening in condensed time intervals. Eight participants experienced multiple homicide deaths in a single year during adolescence. One participant (Antwon, age 18 years) experienced 4 peer homicide deaths within 1 year, the highest frequency of homicide deaths reported in a single year during this developmental period. Nine participants experienced the homicide deaths of loved ones in back-to-back calendar years, with 6 young men surviving multiple homicide deaths within a single year and across sequential calendar years during adolescence.

When Antwon was 17 years old, his best friend and 3 other close peers were murdered in distinct incidents in the same year. Antwon described his experience of interacting with young, physically healthy peers 1 day and learning they were dead the next:

It’s disturbing. It really make you think . . . like you’ll be here one second and the next second you can be gone. Like it made me think about my life, you feel me, the value of my life, and people around me, and things happening to people around me—'Cause in 2011, a lot of people had passed . . . and I was just thinking like can one of us be next? Or somebody else in my family? Somebody I’m really close to?

The frequent and proximal homicide deaths of peers created contexts for young men’s contemplation of mortality. Unable to relocate from their Baltimore neighborhoods, young men questioned if they also would die young and braced themselves for additional experiences of traumatic loss resulting from neighborhood violence. As Kenneth (age 18 years) explained, “I could get shot today or tomorrow. I just want to know, who gonna be at my funeral? That’s why I want to move out of the 'hood. It's just crazy down there. Everybody dying left and right.”

There was little reprieve from the traumatic loss of homicide during emerging adulthood. The highest frequencies of homicide deaths reported during emerging adulthood occurred between the ages of 18 and 20 years, just as young men were transitioning to adulthood (Table 1). A clustering of homicide deaths also occurred during emerging adulthood. Eleven participants experienced a multiplicity of homicide deaths during this developmental stage. One participant experienced 5 peer homicide deaths in 1 calendar year, the highest reported frequency of homicide deaths in a singular year in this sample. Three participants experienced homicide deaths in consecutive years in emerging adulthood, with 2 young men experiencing multiple homicide deaths within a single year and across sequential years during emerging adulthood. Together, these findings suggested that young Black men are particularly burdened by the traumatic loss of homicide during the developmental stages of adolescence and emerging adulthood. These recurrent encounters with violent death cognitively and emotionally exhausted young men. As Myles (age 21 years), a 3-time homicide survivor remarked, “I’m tired of going to funerals.”

DISCUSSION

I examined the life course frequency and developmental timing of traumatic loss and homicide death among young Black men (18–24 years) in Baltimore. Beyond documenting the disparity of homicide death among Black male victims, I uncovered the prevalence of traumatic loss among their surviving networks.6 Participants disclosed experiencing an average of 3 homicide deaths, revealing a multiplicity of losses that were often masked in the singular status of the homicide survivor. The majority of decedents were peers.13

My study advanced our understandings of homicide survivorship among Black males by identifying key windows of vulnerability for experiencing a traumatic loss over the life course.6 Participants' experiences of homicide death started in early childhood, peaked in adolescence, and persisted into emerging adulthood. The proximal nature of peer homicides was most pronounced during adolescence and emerging adulthood. Overall, young men’s LHC suggested the school-age years and adolescence as developmental periods when young Black men reported the highest risk of experiencing their first traumatic loss resulting from homicide.

Study findings also identified the developmental consequences of the disparity of homicide for young Black men. As youths approach adolescence and transitioned to adulthood, the peer group increased in its developmental importance.40–42 During developmental contexts when peer networks were expected to expand,41,42 the off-time homicide deaths of peers contracted the social networks of the young Black men in this sample. The premature deaths of peers to violence also heightened young men’s awareness of their vulnerability to violent death,35 and were identified as turning points.30 Continued research is needed to understand how coming of age in a dying cohort shapes young men’s identity development, decision-making, and health behaviors.13 Future research should also examine how the disparities of homicide and traumatic loss shape young Black men’s levels social support and social capital as they transition to adulthood.

My study highlighted the importance of considering context in research on traumatic loss and homicide survivorship.43 The local conditions of violence experienced by study participants in east Baltimore created unique contexts of protracted vulnerability in which Black males had to negotiate constant threats to their own mortality while processing the deaths of their peers. Young men’s residential location within unsafe neighborhoods might constrain their abilities to process traumatic loss and contribute to unresolved grief.8,44 Future research is needed to examine the impact of context on the grief processes, coping resources, and strategies of Black male homicide survivors in urban communities.

Taken together, my study findings identified the need for trauma and grief informed interventions to support the healthy processing of traumatic loss for Black boys and men across the life course.19 Previous homicide survivorship research identified adverse mental and behavioral health consequences of this experience, including depression,11 PTSD,9 complicated grief,5,10 and substance use.13 Although future research is needed to understand the physical and psychosocial consequences of traumatic loss for young Black men, my study suggested public and mental health practitioners should target prevention efforts earlier in the life course (e.g., in the school age and adolescent years).

Limitations

Although my study broadened the empirical awareness of homicide as a health disparity by examining young Black men's experiences as homicide survivors, it is not without limitations. I did not use a random sampling technique, and my study was only reflective of the experiences of a small sample of young Black men in Baltimore. However, the conditions that perpetuate violence in Baltimore (e.g., unequal educational and employment structures, residential segregation and overcrowding, etc.)16 are reflective of the social determinants of violence in major cities throughout the United States. Therefore, the present results might provide a critical glimpse into the larger experiences of traumatic loss, grief, and homicide survivorship for Black males in other urban centers. Future public health surveillance studies should investigate the experience of homicide survivorship among nationally representative samples.

Accurate recall of the timing of the life events could be a challenge in retrospective interviews.33 In this study, participants might have been particularly challenged in recalling losses experienced in early childhood more than in emerging adulthood. The utilization of adapted LHC methodology (chronologies of loss) helped to reduce recall burden and enhance the trustworthiness of these data. This methodology also addressed a key gap in the literature6 by capturing data on multiple experiences of homicide deaths and identifying key developmental periods when young Black men were increasingly vulnerable to experiencing traumatic loss.

Implications

The results of my study revealed the burdens of traumatic loss experienced by Black boys and men across the life course. Gender socialization, masculinity, and the contextual demands of toughness in economically disadvantaged contexts might constrain young Black men’s abilities to discuss emotional pain connected to the traumatic loss of loved ones to violence.44–50 Conformity to masculine norms (e.g., men do not cry) might contribute to masking behaviors (e.g., substance use) in an effort to manage grief.45–50 In addition to becoming trauma-informed,21,22 my study identified the need for systems serving Black males to become grief-informed.51 Public health professionals working to prevent violence and promote the health and well-being of Black boys and men, particularly those situated in economically disadvantaged inner-city contexts, should be aware of the prevalence of traumatic loss in the lives of this group, assess for experiences of homicide survivorship, and connect youths to appropriate support services.

Developmentally appropriate and culturally competent grief-focused intervention programs should also be designed and implemented across the life course. These programs should consider the cognitive understandings of death across developmental stages, cultural norms about grief expressions and rituals (e.g., public vs private; gendered responses), and community messaging about loss and grief (e.g., “get over the death”). Providing Black boys and men with the opportunity to address experiences of loss and grief might prevent adverse mental health and behavioral consequences associated with homicide survivorship,5,9–13,28 further interrupt the cycle of violence,52 and facilitate healing in the lives of young Black men.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded in part by the Mabel S. Spencer Award for Excellence in Graduate Achievement, an endowed fellowship at the University of Maryland, College Park.

I acknowledge the guidance and expertise of Kevin Roy, PhD, who served as my dissertation chair and who championed my commitment to research in this area. I am especially grateful to the many participants and community programmers who courageously and generously shared their stories, insights, and time with me.

Human Participant Protection

This study was approved by the University of Maryland College Park institutional review board.

References

- 1.Hennekens CH, Drowos J, Levine RS. Mortality from homicide among young Black men: a new American tragedy. Am J Med. 2013;126(4):282–283. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2012.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Murphy SL, Xu JQ, Kochanek KD. Deaths: Final Data for 2010. National Vital Statistics Reports. Vol 61.No 4. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Youth violence: facts at a glance. 2014. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/pdf/yv_datasheet_2012-a.pdf. Accessed May 26, 2014.

- 4.Armour M. Meaning making in the aftermath of homicide. Death Stud. 2003;27(6):519–540. doi: 10.1080/07481180302884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burke LA, Neimeyer RA, McDevitt-Murphy ME. African American homicide bereavement: aspects of social support that predict complicated grief, PTSD, and depression. Omega. 2010;61(1):1–24. doi: 10.2190/OM.61.1.a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hertz MF, Prothrow-Stith D, Chery C. Homicide survivors: research and practice implications. Am J Prev Med. 2005;29(5 suppl 2):288–295. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2005.08.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sharpe TL, Boyas J. We fall down: the African American experience of coping with the homicide of a loved one. J Black Stud. 2011;42(6):855–873. doi: 10.1177/0021934710377613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rando TA. Treatment of Complicated Mourning. Champaign, IL: Research Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Amick-McMullan A, Kilpatrick DG, Resnick HS. Homicide as a risk factor for PTSD among surviving family members. Behav Modif. 1991;15(4):545–559. doi: 10.1177/01454455910154005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Johnson CM. When African American teen girls’ friends are murdered: a qualitative study of bereavement, coping, and psychosocial consequences. Fam Soc. 2010;91(4):364–370. [Google Scholar]

- 11.McDevitt-Murphy ME, Neimeyer RA, Burke LA, Williams JL, Lawson K. The toll of traumatic loss in African Americans bereaved by homicide. Psychol Trauma. 2012;4(3):303–311. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sharpe TL, Joe S, Taylor KC. Suicide and homicide bereavement among African Americans: implications for survivor research and practice. Omega (Westport) 2012–2013;66(2):153–172. doi: 10.2190/om.66.2.d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zinzow HM, Rheingold AA, Hawkins AO, Saunders BE, Kilpatrick DG. Losing a loved one to homicide: prevalence and mental health correlates in a national sample of young adults. J Trauma Stress. 2009;22(1):20–27. doi: 10.1002/jts.20377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Finkelhor D, Ormrod R, Turner H, Hamby SL. The victimization of children and youth: a comprehensive, national survey. Child Maltreat. 2005;10(1):5–25. doi: 10.1177/1077559504271287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Halfon N, Larson K, Russ S. Why social determinants? Healthc Q. 2010;14(sp 1):8–20. doi: 10.12927/hcq.2010.21979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shonkoff JP, Garner AS, Siegel BS et al. The lifelong effects of early childhood adversity and toxic stress. Pediatrics. 2012;129(1):e232–e246. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-2663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bryant R. Taking Aim at Gun Violence: Rebuilding Community Education and Employment. Washington, DC: CLASP; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Buka SL, Stichick TL, Birdthistle I, Felton SM. Youth exposure to violence: prevalence, risks, and consequences. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 2001;71(3):298–310. doi: 10.1037/0002-9432.71.3.298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Peterson RD, Krivo LJ. Racial segregation, the concentration of disadvantage, and Black and White homicide victimization. Sociol Forum. 1999;14(3):465–493. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rasmussen A, Aber MS, Bhana A. Adolescent coping and neighborhood violence: perceptions, exposure, and urban youths’ efforts to deal with danger. Am J Community Psychol. 2004;33(1–2):61–75. doi: 10.1023/b:ajcp.0000014319.32655.66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rich J, Corbin T, Bloom S, Evans S, Wilson A. Healing the hurt: approaches to the health of boys and young men of color. The California Endowment Fund. 2009. Available at: http://www.calendow.org/uploadedFiles/Publications/BMOC/Drexel%20-%20Healing%20the%20Hurt%20-%20Full%20Report.pdf. Accessed June 15, 2014.

- 22.Rich JA. Wrong Place, Wrong Time: Trauma and Violence in the Lives of African American Men. Baltimore, MD: The Johns Hopkins University Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rivera A, Huezo J, Kasica C, Muhammad D. The silent depression: state of the dream. 2009. Available at: http://www.faireconomy.org/files/pdf/state_of_dream_2009.pdf. Accessed June 23, 2014.

- 24.The Baltimore Sun. Baltimore homicides. Available at: http://data.baltimoresun.com/homicides. Accessed June 17, 2014.

- 25.Bordere TC. “To look at death another way”: Black teenage males’ perspectives on second-line and regular funerals in New Orleans. Omega (Westport) 2008-2009;58(3):213–232. doi: 10.2190/om.58.3.d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Halfon N, Hochstein M. Life course health development: an integrated framework for developing health, policy, and research. Milbank Q. 2002;80(3):433–479. doi: 10.1111/1468-0009.00019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Halfon N. Addressing health inequities in the US: a life course health development approach. Soc Sci Med. 2012;74(5):671–673. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Laurie A, Neimeyer RA. African Americans in bereavement: grief as a function of ethnicity. Omega. 2008;57(2):173–193. doi: 10.2190/OM.57.2.d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Elder GH, Giele JZ. The Craft of Life Course Research. New York, NY: The Guildford Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Giele J, Elder GH. Life course research: development of a field. In: Giele J, Elder GH, editors. Methods of Life Course Research: Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1998. pp. 5–27. [Google Scholar]

- 31.LaRossa R. Grounded theory methods and qualitative family research. J Marriage Fam. 2005;67(4):837–857. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Daly K. Qualitative Methods for Family Studies and Human Development. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Axinn WG, Pearce LD. Mixed Method Data Collection Strategies. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nelson IA. From quantitative to qualitative: adapting the life history calendar method. Field Methods. 2010;22(4):413–428. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Smith J. College Park, MD: University of Maryland, College Park; 2013. Peer homicide and traumatic loss: an examination of homicide survivorship among low-income, young, Black men [dissertation] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Baltimore Neighborhood Indicators Alliance – Jacob France Institute. Vital Signs 12. [data file]. 2013. Available at: http://www.bniajfi.org/vital_signs. Accessed November 12, 2014.

- 37.Emerson R, Fretz R, Shaw L. Writing Ethnographic Field Notes. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press; 1997. Coding and memoing; pp. 142–168. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Patton MQ. Qualitative Research and Evaluation Methods. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lincoln Y, Guba E. Naturalistic Inquiry. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Settersten RA., Jr Passages to adulthood: linking demographic change and human development. Eur J Popul. 2007;23(3–4):251–272. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Settersten RA, Jr., Ray B. What’s going on with young people today? The long and twisting path to adulthood. Future Child. 2010;20(1):19–41. doi: 10.1353/foc.0.0044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Balk DE, Corr CA. Adolescent Encounters with Death, Bereavement, and Coping. New York, NY: Springer; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Malone PA. The impact of peer death on adolescent girls: a task-oriented group intervention. J Soc Work End Life Palliat Care. 2007;3(3):23–37. doi: 10.1300/J457v03n03_04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Podell C. Adolescent mourning: the sudden death of a peer. Clin Social Work J. 1989;17(1):64–78. [Google Scholar]

- 45. Medline Plus. School-age children development. 2012. Available at: http://www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/ency/article/002017.htm. Accessed June 29, 2014.

- 46.Majors R, Billson JM. Cool Pose: The Dilemmas of Black Manhood in America. New York, NY: Lexington Books; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mejía XE. Gender matters: working with adult male survivors of trauma. J Couns Dev. 2005;83:29–40. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hall RE, Pizarro JM. Cool pose: Black male homicide and the social implications of manhood. J Soc Serv Res. 2010;37(1):86–98. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kivel P. Boys will be men: guiding your sons from boyhood to manhood. 2006. Available at: http://www.paulkivel.com/issues/gender-justice/item/55-boys-will-be-men-guiding-your-sons-from-boyhood-to-manhood. Accessed July 1, 2014.

- 50.Lund DA, editor. Men Coping With Grief. New York, NY: Baywood Publishing Company, Inc; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kaplow JB, Layne CM, Saltzman WR, Cozza SJ, Pynoos RS. Using multidimensional grief theory to explore the effects of deployment, reintegration, and death on military youth and families. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev. 2013;16(3):322–340. doi: 10.1007/s10567-013-0143-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rich JA, Grey CM. Pathways to recurrent trauma among young Black men: traumatic stress, substance use, and the “code of the street.”. Am J Public Health. 2005;95(5):816–824. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.044560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]