Abstract

The near-visible-to-blue singlet fluorescence of anthracene sensitized by a ruthenium chromophore with a long-lived triplet-excited state, [Ru(5-pyrenyl-1,10-phenanthroline)3](PF6)2, in acetonitrile was investigated. Low intensity non-coherent green light was used to selectively excite the sensitizer in the presence of micromolar concentrations of anthracene generating anti-Stokes, singlet fluorescence in the latter, even with incident power densities below 500 μW cm−2. The resultant data are consistent with photon upconversion proceeding from sensitized triplet–triplet annihilation (TTA) of the anthracene acceptor molecules, confirmed through transient absorption spectroscopy as well as static and dynamic photoluminescence experiments. Additionally, quadratic-to-linear incident power regimes for the upconversion process were identified for this composition under monochromatic 488 nm excitation, consistent with a sensitized TTA mechanism ultimately producing the anti-Stokes emission characteristic of anthracene singlet fluorescence.

Keywords: photon upconversion, triplet–triplet annihilation, anti-Stokes emission, molecular photophysics, wavelength shifting

1. Introduction

Photon upconversion (UC) based on sensitized triplet–triplet annihilation (TTA) was first introduced in the early 1960s by Parker & Hatchard [1,2]. Since its inception, photon UC has been recognized as a viable technology for exceeding the Shockley–Queisser limit in photovoltaics by creating a mechanism through which sub-bandgap photons can be captured and converted into photocurrent [3–11]. Apart from that, a variety of potential applications for TTA upconversion have been proposed in the literature, e.g. bioimaging and biocompatible materials in aqueous environments [12–16], cycloaddition chemistry using visible light excitation [17] and photoelectrochemical cells [18,19]. The mechanism of photon UC through sensitized TTA proceeds using two sequential bimolecular energy transfers: (i) selective excitation of a strongly absorbing sensitizer chromophore that initiates triplet–triplet energy transfer (TTET) between the excited triplet sensitizer and a triplet acceptor moiety and (ii) TTA energy transfer between two triplet-excited acceptors. During the TTA step, one of the acceptor molecules transfers its energy to the other effectively promoting the latter to an excited singlet state that is higher in energy than the incident light resulting in P-type, anti-Stokes delayed fluorescence. Based on this mechanism, it is clear that there are specific energetic and kinetic requirements that enable photon UC to occur [20–24]. Namely, in most cases the triplet state of the acceptor must be lower in energy than the triplet state of the sensitizer and both triplet states must be long lived (e.g. microseconds) as the TTA process is bimolecular and relies on diffusional interactions; furthermore, the singlet state of the acceptor must be higher energy than the singlet state of the sensitizer, yet less than or equal to twice the energy of the triplet state of the acceptor (scheme 1) [25,26]. Thus, metal-containing chromophores with long-lived triplet states make desirable triplet sensitizers because the energy and excited state lifetimes of the singlet and triplet states can be rationally tuned by ligand modification [27,28]. Consequently, tremendous advancements have been achieved in photochemical upconversion by using metal-containing triplet sensitizers with a variety of organic-based triplet acceptors/annihilators in both fluid solution [20,22,29–32] and various host matrices [33–43].

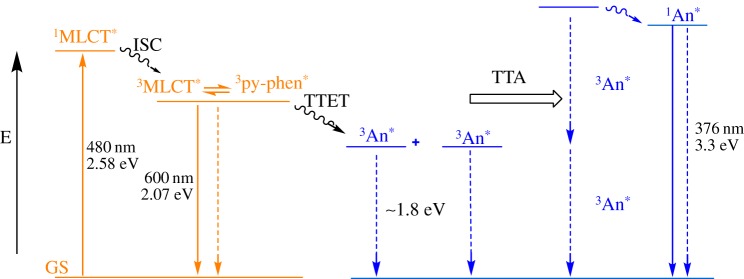

Scheme 1.

Qualitative Jablonski diagram illustrating sensitized TTA-based upconversion occurring between  and anthracene as well as the associated energetics of their singlet- and triplet-excited states. (Online version in colour.)

and anthracene as well as the associated energetics of their singlet- and triplet-excited states. (Online version in colour.)

The ultimate goal of this research is to maximize the efficiency of real-world solar powered devices by imparting sub-bandgap sensitization via integration of UC technology [8–10,44,45]. This change in cell design should reduce the drastic losses owing to spectral mismatch between various sensitizers and semiconductor bandgaps. However, there are several critical properties of these systems that must be optimized for this technology to be viable for incorporation into real-world applications. First, because the photon UC via sensitized TTA process occurs through diffusional, bimolecular chemistry, the measurement and improvement of the quantum efficiency in these systems becomes crucial [20,22,35,46]. Second, in order to reap the greatest benefits from these compositions, it is necessary to maximize the anti-Stokes shift that can be achieved. Therefore, many research efforts have focused on investigating triplet sensitizers that absorb incident radiation in the visible and near-IR regions of the spectrum in combination with a variety of energetically relevant acceptors/annihilators [34,47–51]. Finally, although TTA is inherently a non-coherent process which is of much higher efficiency than lanthanide upconverters, only a handful of studies have achieved detectable photon UC in the absence of laser excitation [7,18,33,52,53]. This premise inspired the present contribution, wherein we successfully demonstrate low-power, non-coherent, green-to-blue and near-visible photon UC using a ruthenium chromophore with a notably long-lived metal-to-ligand charge transfer (MLCT) triplet state, [Ru(5-pyrenyl-1,10-phenanthroline)3](PF6)2 (Ru(py-phen) , τ=148±8 μs) [54], along with anthracene as the acceptor/annihilator in deoxygenated CH3CN solutions. Scheme 1 depicts the relevant energetics of the Ru(II) sensitizer and the anthracene acceptors/annihilators, wherein the sensitizer singlet/triplet states are strategically sandwiched between the singlet/triplet levels of the anthryl chromophores. This ensures the selective excitation of the sensitizer at long wavelengths and minimal spectral overlap of the anthryl singlet fluorescence with that of the low energy transitions of the MLCT sensitizer. The extended triplet-excited state lifetime of the Ru(II) complex results from a reservoir effect with the appended pyrenyl chromophores that effectively stores the excited state energy in the triplet state of pyrene that is in thermal equilibrium with the MLCT excited state responsible for its RT photoluminescence [55]. The net result is an excited state lifetime that is significantly longer than a typical Ru(II) MLCT chromophore, but shorter lived with respect to the pure triplet-excited state of pyrene, making it more susceptible to bimolecular chemistry such as TTET. A recent example of a lifetime extended Ru(II) chromophore used as a sensitizer in photochemical upconversion suggests the viability of the strategy outlined in Scheme 1 [56].

, τ=148±8 μs) [54], along with anthracene as the acceptor/annihilator in deoxygenated CH3CN solutions. Scheme 1 depicts the relevant energetics of the Ru(II) sensitizer and the anthracene acceptors/annihilators, wherein the sensitizer singlet/triplet states are strategically sandwiched between the singlet/triplet levels of the anthryl chromophores. This ensures the selective excitation of the sensitizer at long wavelengths and minimal spectral overlap of the anthryl singlet fluorescence with that of the low energy transitions of the MLCT sensitizer. The extended triplet-excited state lifetime of the Ru(II) complex results from a reservoir effect with the appended pyrenyl chromophores that effectively stores the excited state energy in the triplet state of pyrene that is in thermal equilibrium with the MLCT excited state responsible for its RT photoluminescence [55]. The net result is an excited state lifetime that is significantly longer than a typical Ru(II) MLCT chromophore, but shorter lived with respect to the pure triplet-excited state of pyrene, making it more susceptible to bimolecular chemistry such as TTET. A recent example of a lifetime extended Ru(II) chromophore used as a sensitizer in photochemical upconversion suggests the viability of the strategy outlined in Scheme 1 [56].

2. Experimental section

(a). General information

[Ru(5-pyrenyl-1,10-phenanthroline)3](PF6)2 (Ru(py-phen) ) was available from our previous studies [57]. Anthracene and spectroscopic grade acetonitrile (CH3CN) were purchased from Aldrich Chemical Company and used as received.

) was available from our previous studies [57]. Anthracene and spectroscopic grade acetonitrile (CH3CN) were purchased from Aldrich Chemical Company and used as received.

(b). Spectroscopic measurements

The static absorption spectra were measured with a Cary 50 Bio UV–Vis spectrophotometer from Varian. Steady-state photoluminescence spectra were recorded using a QM-4/2006SE fluorescence spectrometer obtained from Photon Technologies Incorporated or a FL/FS920 spectrometer from Edinburgh Instruments. Excitation was achieved by an Argon ion laser (Coherent Innova 300) or a 450 W Xe arc lamp. The incident laser or lamp power was varied using a series of neutral density filters placed in front of the sample. Single wavelength emission intensity decays were acquired with a nitrogen-pumped broadband dye laser (2–3 nm fwhm) from PTI (model GL-3300 N2 laser and model GL-301 dye laser) whose details have been previously described [29,58]. Coumarin 450 was used to tune the unfocused, pulsed excitation beam for selectively exciting Ru(py-phen) . All luminescence samples were prepared in specially designed 1 cm2 optical cells each bearing a sidearm round bottom flask and were subjected to a minimum of three freeze–pump–thaw degas cycles prior to all measurements. The laser and lamp power were measured using either a Molectron Power Max 5200 power metre or an OphirNova II/PD300-UV power metre.

. All luminescence samples were prepared in specially designed 1 cm2 optical cells each bearing a sidearm round bottom flask and were subjected to a minimum of three freeze–pump–thaw degas cycles prior to all measurements. The laser and lamp power were measured using either a Molectron Power Max 5200 power metre or an OphirNova II/PD300-UV power metre.

(c). Laser flash photolysis

Nanosecond-transient absorption measurements were acquired on a LP 920 laser flash photolysis system from Edinburgh Instruments equipped with a PMT (R928 Hamamatsu) or an Andor iStar iCCD detector. Excitation of the samples in these experiments was accomplished using a Nd:YAG/OPO laser system from OPOTEK (Vibrant 355 LD-UVM) operating at 1 Hz. The incident laser power was varied using a series of neutral density filters or by appropriately modifying the Q-switch delay.

3. Results and discussion

The normalized ground state absorption and emission characteristics of the Ru(py-phen) sensitizer and the anthracene acceptor/annihilator were examined in CH3CN to determine if the photon UC via sensitized TTA process would be facile, as presented in figure 1. The Ru(py-phen)

sensitizer and the anthracene acceptor/annihilator were examined in CH3CN to determine if the photon UC via sensitized TTA process would be facile, as presented in figure 1. The Ru(py-phen) sensitizer exhibits characteristic absorptions between 300 and 350 nm (π-π* absorption bands) along with dπ (Ru) →π*(py-phen) MLCT transition features at lower energy (400–500 nm) and charge transfer photoluminescence centred at 600 nm in deaerated CH3CN. Anthracene possesses intense absorption bands at 376 nm and 357 nm with two side smaller vibronic transitions at 340 nm and 324 nm. The fluorescence spectrum of anthracene displays mirror image symmetry with its absorption spectrum, having four emission maxima at 380, 401, 424 and 450 nm. Therefore, it is possible to selectively excite the Ru(py-phen)

sensitizer exhibits characteristic absorptions between 300 and 350 nm (π-π* absorption bands) along with dπ (Ru) →π*(py-phen) MLCT transition features at lower energy (400–500 nm) and charge transfer photoluminescence centred at 600 nm in deaerated CH3CN. Anthracene possesses intense absorption bands at 376 nm and 357 nm with two side smaller vibronic transitions at 340 nm and 324 nm. The fluorescence spectrum of anthracene displays mirror image symmetry with its absorption spectrum, having four emission maxima at 380, 401, 424 and 450 nm. Therefore, it is possible to selectively excite the Ru(py-phen) MLCT bands between 400 and 500 nm to generate long-lived phosphorescence at 600 nm. Unfortunately, significant overlap of the anthracene fluorescence signal and the MLCT region of the Ru(py-phen)

MLCT bands between 400 and 500 nm to generate long-lived phosphorescence at 600 nm. Unfortunately, significant overlap of the anthracene fluorescence signal and the MLCT region of the Ru(py-phen) indicates that some of the resulting upconverted light will be lost to re-excitation of the sensitizer, which ultimately limits the potential quantum yields that can be extracted from this composition. The self-quenching of the Ru(py-phen)

indicates that some of the resulting upconverted light will be lost to re-excitation of the sensitizer, which ultimately limits the potential quantum yields that can be extracted from this composition. The self-quenching of the Ru(py-phen) sensitizer also shortens the lifetime from τ=148 μs, measured under optically dilute conditions, to τ≈50 μs measured under the conditions necessary for efficient UC, which is revealed in the Ksv measurement discussed below.

sensitizer also shortens the lifetime from τ=148 μs, measured under optically dilute conditions, to τ≈50 μs measured under the conditions necessary for efficient UC, which is revealed in the Ksv measurement discussed below.

Figure 1.

The absorption and photoluminescence spectra of  and anthracene measured in CH3CN. (Online version in colour.)

and anthracene measured in CH3CN. (Online version in colour.)

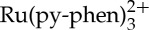

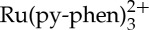

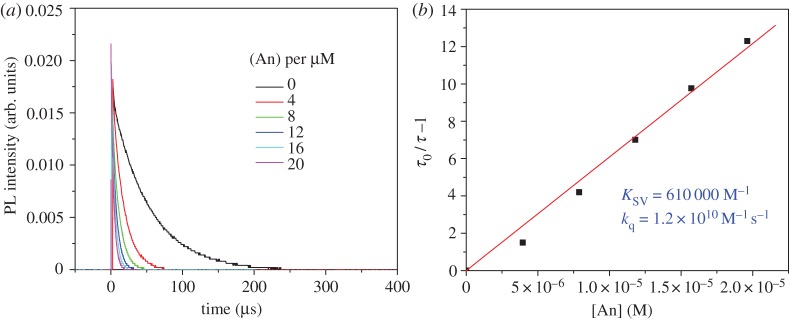

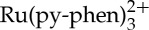

As mentioned previously, the first step in the photon UC via sensitized TTA process is a TTET from two selectively excited sensitizer molecules to the triplet state of two anthryl acceptor molecules. Therefore, the quenching behaviour of the triplet-excited state of  by anthracene was investigated by Stern–Volmer analysis of the luminescence intensity decays as well as through nanosecond-transient absorption spectroscopy kinetics. In order to extract a Stern–Volmer quenching constant for this sensitizer–acceptor/annihilator pair, the luminescence intensity decay of

by anthracene was investigated by Stern–Volmer analysis of the luminescence intensity decays as well as through nanosecond-transient absorption spectroscopy kinetics. In order to extract a Stern–Volmer quenching constant for this sensitizer–acceptor/annihilator pair, the luminescence intensity decay of  was evaluated as a function of anthracene concentration in vacuum degassed CH3CN solution. Satisfactory fits were generated using a single exponential function for each of the decay curves obtained in these experiments, and luminescence lifetimes (τ) were easily extracted from these fits. The lifetime values were used to generate the Stern–Volmer plot shown in figure 2 revealing a very large Stern–Volmer constant (KSV) of 610 000 M−1, which is consistent with the 50 μs lifetime of the sensitizer in the absence of anthryl quenchers, implying that extremely low acceptor concentrations are suitable for quantitative quenching of the MLCT sensitizer. As stated above the value of τ0 here and used in the Stern–Volmer calculations is actually 50 μs as there is a significant amount of self-quenching (likely TTA between excited sensitizer molecules) that shortens the sensitizer lifetime but does not interfere with its ability to promote photochemical upconversion. This is clearly noted from the magnitude of the TTET rate constant of 1.2×1010 M−1 s−1 extracted from the Stern–Volmer plot in figure 2b and τ0=50 μs, which approaches the diffusion limit in this solvent [59].

was evaluated as a function of anthracene concentration in vacuum degassed CH3CN solution. Satisfactory fits were generated using a single exponential function for each of the decay curves obtained in these experiments, and luminescence lifetimes (τ) were easily extracted from these fits. The lifetime values were used to generate the Stern–Volmer plot shown in figure 2 revealing a very large Stern–Volmer constant (KSV) of 610 000 M−1, which is consistent with the 50 μs lifetime of the sensitizer in the absence of anthryl quenchers, implying that extremely low acceptor concentrations are suitable for quantitative quenching of the MLCT sensitizer. As stated above the value of τ0 here and used in the Stern–Volmer calculations is actually 50 μs as there is a significant amount of self-quenching (likely TTA between excited sensitizer molecules) that shortens the sensitizer lifetime but does not interfere with its ability to promote photochemical upconversion. This is clearly noted from the magnitude of the TTET rate constant of 1.2×1010 M−1 s−1 extracted from the Stern–Volmer plot in figure 2b and τ0=50 μs, which approaches the diffusion limit in this solvent [59].

Figure 2.

Stern–Volmer analysis of dynamic quenching between the  excited state and anthracene in vacuum degassed CH3CN. (Online version in colour.)

excited state and anthracene in vacuum degassed CH3CN. (Online version in colour.)

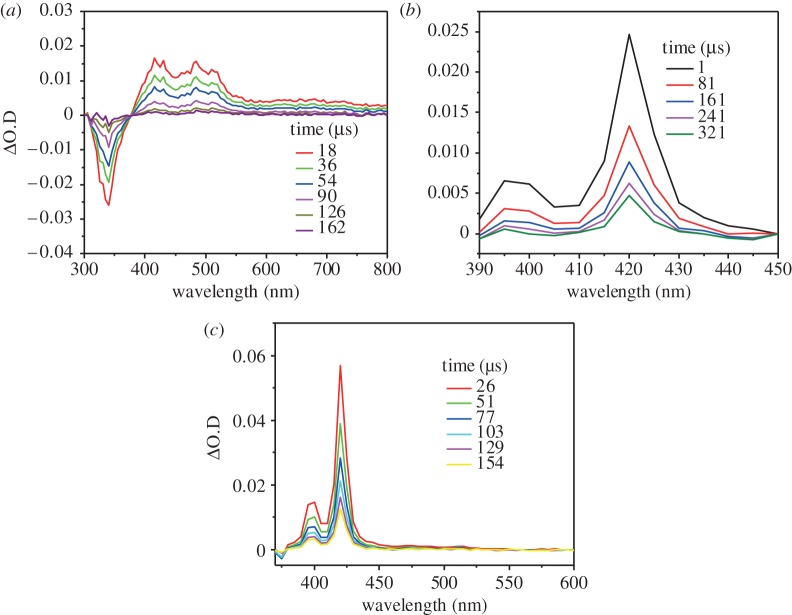

In order to verify that the observed luminescence quenching is indeed due to TTET, independent laser flash photolysis experiments were performed to elucidate the characteristic differences between the absorption transients associated with the Ru(py-phen) sensitizer and the T1→Tn transitions in the anthracene acceptor/annihilator. The transient absorption difference spectra of Ru(py-phen)

sensitizer and the T1→Tn transitions in the anthracene acceptor/annihilator. The transient absorption difference spectra of Ru(py-phen) and anthracene independently measured as a function of delay time are presented in figure 3a,b. These spectra are directly compared with the transient absorption difference spectrum obtained from a mixed solution containing both Ru(py-phen)

and anthracene independently measured as a function of delay time are presented in figure 3a,b. These spectra are directly compared with the transient absorption difference spectrum obtained from a mixed solution containing both Ru(py-phen) and anthracene, presented in figure 3c. As can be seen when comparing figure 3a,c, the characteristic bleaching signal at long delay times associated with Ru(py-phen)

and anthracene, presented in figure 3c. As can be seen when comparing figure 3a,c, the characteristic bleaching signal at long delay times associated with Ru(py-phen) is no longer observable in the spectral signature obtained for the Ru(py-phen)

is no longer observable in the spectral signature obtained for the Ru(py-phen) /anthracene mixture. Furthermore, identical transient features are observed in figure 3b, the characteristic spectrum of the anthracene triplet (3An*), and figure 3c, the spectrum obtained from the Ru(py-phen)

/anthracene mixture. Furthermore, identical transient features are observed in figure 3b, the characteristic spectrum of the anthracene triplet (3An*), and figure 3c, the spectrum obtained from the Ru(py-phen) anthracene mixture. These two observations together indicate complete transfer of absorbed photons from the Ru(py-phen)

anthracene mixture. These two observations together indicate complete transfer of absorbed photons from the Ru(py-phen) triplet to the sensitized anthryl triplets in the chromophore mixture. Thus, these laser flash photolysis experiments demonstrate that the selective excitation of Ru(py-phen)

triplet to the sensitized anthryl triplets in the chromophore mixture. Thus, these laser flash photolysis experiments demonstrate that the selective excitation of Ru(py-phen) results in the T1→Tn absorption spectrum characteristic of 3An* in the mixed solution, verifying that the MLCT photoluminescence quenching proceeds exclusively through TTET.

results in the T1→Tn absorption spectrum characteristic of 3An* in the mixed solution, verifying that the MLCT photoluminescence quenching proceeds exclusively through TTET.

Figure 3.

(a) Transient absorption difference spectrum of 44 μM Ru(py-phen) freeze–pump–thaw degassed CH3CN solution measured at several delay times, 3.0 mJ pulse−1, λexc=460 nm. (b) Transient absorption difference spectrum of 0.14 mM anthracene freeze–pump–thaw degassed CH3CN solution measured at several delay times, 3.0 mJ pulse−1, λexc=355 nm. (c) Transient absorption difference spectrum of 44 μM Ru(py-phen)

freeze–pump–thaw degassed CH3CN solution measured at several delay times, 3.0 mJ pulse−1, λexc=460 nm. (b) Transient absorption difference spectrum of 0.14 mM anthracene freeze–pump–thaw degassed CH3CN solution measured at several delay times, 3.0 mJ pulse−1, λexc=355 nm. (c) Transient absorption difference spectrum of 44 μM Ru(py-phen) and 0.19 mM anthracene freeze–pump–thaw degassed CH3CN measured at several delay times, 3.0 mJ pulse−1, λexc=460 nm. (Online version in colour.)

and 0.19 mM anthracene freeze–pump–thaw degassed CH3CN measured at several delay times, 3.0 mJ pulse−1, λexc=460 nm. (Online version in colour.)

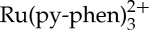

Recall that the sensitized TTA mechanism occurs through a bimolecular interaction of two acceptor/annihilator molecules to produce one higher lying fluorescent singlet state. Two kinetic limits exist in the sensitized TTA process; (i) the weak annihilation regime, in which the UC fluorescence intensity displays a characteristic quadratic dependence relative to incident light power because the rate of TTA is dependent on the first-order triplet decay of the acceptor/annihilator, typically limited by dissolved O2, and (ii) the strong annihilation regime, in which the UC fluorescence yield displays a linear dependence relative to incident light power because the UC fluorescence intensity is dominated by the second-order TTA process [23]. Recently, strategies have been presented that lead to strong annihilation behaviour at low incident photon flux wherein the upconversion efficiency is maximized [60].

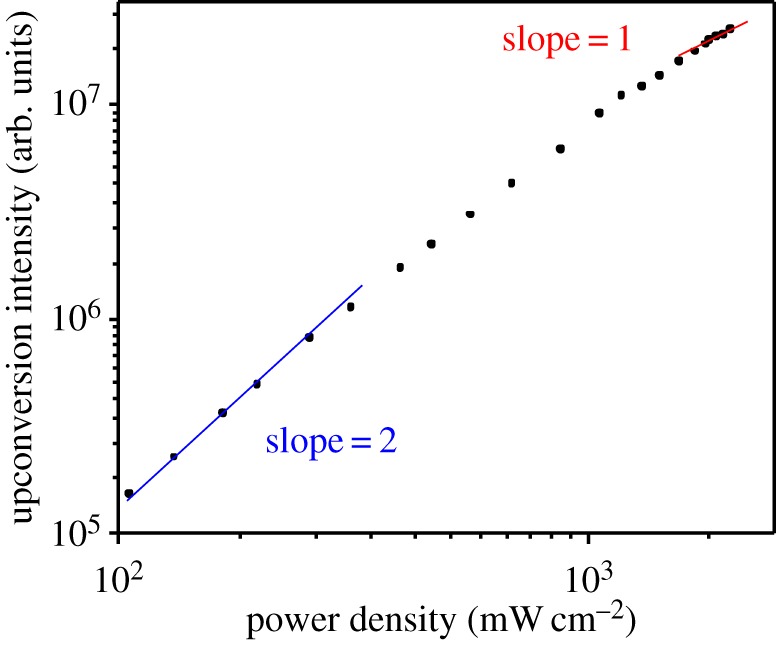

In order to determine the power regimes of the weak and strong annihilation limits for this sensitizer/acceptor/annihilator combination, the intensity of the anthracene singlet fluorescence was measured as a function of incident power density after selective excitation of Ru(py-phen) using a bandpass filtered 488 nm output from an Ar+ laser. Figure 4 presents the double logarithmic plot generated from these experiments, which provides a good illustration of the changeover in the power law response occurring as a result of changes in kinetic regime dominating triplet state decay in the acceptor/annihilator. As anticipated, the slope of this plot was found to be 2.0 at low incident power, which indicates that the upconversion intensity has a quadratic dependence on the incident 488 nm laser power density. Upon increasing the incident photon flux on the sample, the plot deviates off this initial slope, a process that perpetuates until the sample ultimately achieves a slope of 1.0 at the highest incident power densities, illustrating that the photochemical upconversion process has reached the strong annihilation regime.

using a bandpass filtered 488 nm output from an Ar+ laser. Figure 4 presents the double logarithmic plot generated from these experiments, which provides a good illustration of the changeover in the power law response occurring as a result of changes in kinetic regime dominating triplet state decay in the acceptor/annihilator. As anticipated, the slope of this plot was found to be 2.0 at low incident power, which indicates that the upconversion intensity has a quadratic dependence on the incident 488 nm laser power density. Upon increasing the incident photon flux on the sample, the plot deviates off this initial slope, a process that perpetuates until the sample ultimately achieves a slope of 1.0 at the highest incident power densities, illustrating that the photochemical upconversion process has reached the strong annihilation regime.

Figure 4.

Double logarithmic plot of the upconversion emission signal at 430 nm measured as a function of 488 nm incident laser power density in a mixture of Ru(py-phen) (15 μM) and anthracene (0.17 mM) in freeze–pump–thaw degassed CH3CN. The solid lines are the linear fits with slopes of 1.0 (red, linear response) and 2.0 (blue, quadratic response) in the high- and low-power regimes, respectively. (Online version in colour.)

(15 μM) and anthracene (0.17 mM) in freeze–pump–thaw degassed CH3CN. The solid lines are the linear fits with slopes of 1.0 (red, linear response) and 2.0 (blue, quadratic response) in the high- and low-power regimes, respectively. (Online version in colour.)

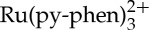

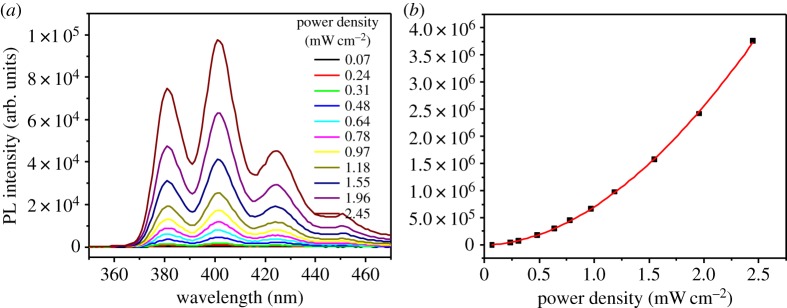

As the goal of this project is to evaluate upconversion compositions intended for real-world solar photon capture and conversion devices, this sensitizer/acceptor/annihilator combination was tested using ultra-low non-coherent excitation on the micromolar concentration scale for sensitizer and acceptor/annihilator. Instead of exciting with the 488 nm line from an Ar+ laser, a 450 W Xe arc lamp equipped with a monochromator was used to give excitation power densities from 70 μW cm−2 to 2.45 mW cm−2 at 480 nm. A 455 nm long pass filter was incorporated into the experimental set-up to avoid direct excitation of anthracene from lower monochromator diffraction orders. The power dependence of this sample using this non-coherent excitation source was evaluated, figure 5, clearly indicating quadratic power dependence. Although the anti-Stokes fluorescence intensity generated using these experimental conditions occurs in the weak annihilation limit, photochemical upconversion operating under such low-power excitation conditions (down to the μW cm−2 scale) is important with regard to future device integration. Ideally, devices incorporating photochemical upconversion technology are poised to exceed the Shockley–Queisser limit that is ultimately responsible for the major part of the thermodynamic efficiency losses in solar powered devices.

Figure 5.

(a) Upconverted emission intensity profile of a mixture of Ru(py-phen) (31 μM) and anthracene (51 μM) in freeze–pump–thaw degassed CH3CN as a function of 480 nm Xe arc lamp excitation. (b) Integrated emission intensity from (a) as a function of the incident power density. The red line is the best quadratic fit (χ2) to the data. (Online version in colour.)

(31 μM) and anthracene (51 μM) in freeze–pump–thaw degassed CH3CN as a function of 480 nm Xe arc lamp excitation. (b) Integrated emission intensity from (a) as a function of the incident power density. The red line is the best quadratic fit (χ2) to the data. (Online version in colour.)

4. Conclusion

The current photochemical upconversion composition demonstrated that selective long wavelength excitation of Ru(py-phen) with both coherent and non-coherent photons in the presence of anthracene results in upconverted blue and near-visible emission in deareated CH3CN.The sensitized TTA process was confirmed using a variety of spectroscopic measurements including static and dynamic photoluminescence in addition to transient absorption spectroscopy. Non-coherent photons down to ultra-low intensities (on the order of μW cm−2) were used for selective sensitizer excitation in the presence of micromolar concentrations of anthracene, generating anti-Stokes singlet fluorescence in the latter. This combination of chromophores represents a viable combination to achieve sub-bandgap photon capture and conversion in wide-bandgap metal oxide semiconductors.

with both coherent and non-coherent photons in the presence of anthracene results in upconverted blue and near-visible emission in deareated CH3CN.The sensitized TTA process was confirmed using a variety of spectroscopic measurements including static and dynamic photoluminescence in addition to transient absorption spectroscopy. Non-coherent photons down to ultra-low intensities (on the order of μW cm−2) were used for selective sensitizer excitation in the presence of micromolar concentrations of anthracene, generating anti-Stokes singlet fluorescence in the latter. This combination of chromophores represents a viable combination to achieve sub-bandgap photon capture and conversion in wide-bandgap metal oxide semiconductors.

Funding statement

This research was supported by the Air Force Office of Scientific Research (FA9550-13-1-0106).

References

- 1.Parker CA, Hatchard CG. 1962. Sensitized anti-Stokes delayed fluorescence. Proc. Chem. Soc. 386–387. ( 10.1039/PS9620000373) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Parker CA. 1963. Sensitized P-type delayed fluorescence. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. A 276, 125–135. ( 10.1098/rspa.1963.0197) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.de Wild J, Meijerink A, Rath JK, van Sark WGJHM, Schropp REI. 2011. Upconverter solar cells: materials and applications. Energy Environ. Sci. 4, 4835–4848. ( 10.1039/C1EE01659H) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Trupke T, Green MA, Würfel P. 2002. Improving solar cell efficiencies by up-conversion of sub-band-gap light. J. Appl. Phys. 92, 4117 ( 10.1063/1.1505677) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shalav A, Richards BS, Green MA. 2007. Luminescent layers for enhanced silicon solar cell performance: up-conversion. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 91, 829–842. ( 10.1016/j.solmat.2007.02.007) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Green MA. 2005. Third generation photovoltaics: advanced solar energy conversion, 2nd edn Berlin, Germany: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baluschev S, Miteva T, Yakutkin V, Nelles G, Yasuda A, Wegner G. 2006. Up-conversion fluorescence: noncoherent excitation by sunlight. Phys. Rev. Lett. 97, 143903 ( 10.1103/PhysRevLett.97.143903) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cheng YY, et al. 2012. Improving the light-harvesting of amorphous silicon solar cells with photochemical upconversion. Energy Environ. Sci. 5, 6953–6959. ( 10.1039/C2EE21136J) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schulze TF, et al. 2012. Efficiency enhancement of organic and thin-film silicon solar cells with photochemical upconversion. J. Phys. Chem. C 116, 22794–22801. ( 10.1021/jp309636m) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nattestad A, et al. 2013. Dye-sensitized solar cell with integrated triplet–triplet annihilation upconversion system. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 4, 2073–2078. ( 10.1021/jz401050u) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Atre AC, García-Etxarri A, Alaeian H, Dionne JA. 2012. Toward high-efficiency solar upconversion with plasmonic nanostructures. J. Opt. 14, 024008 ( 10.1088/2040-8978/14/2/024008) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim J-H, Kim J-H. 2012. Encapsulated triplet–triplet annihilation-based upconversion in the aqueous phase for sub-band-gap semiconductor photocatalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 17478–17481. ( 10.1021/ja308789u) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu Q, Yang T, Feng W, Li F. 2012. Blue-emissive upconversion nanoparticles for low-power-excited bioimaging in vivo. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 5390–5397. ( 10.1021/ja3003638) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu Q, Yin B, Yang T, Yang Y, Shen Z, Yao P, Li F. 2013. A general strategy for biocompatible, high-effective upconversion nanocapsules based on triplet–triplet annihilation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 5029–5037. ( 10.1021/ja3104268) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Turshatov A, Busko D, Baluschev S, Miteva T, Landfester K. 2011. Micellar carrier for triplet–triplet annihilation-assisted photon energy upconversion in a water environment. New J. Phys. 13, 083035 ( 10.1088/1367-2630/13/8/083035) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Penconi M, Gentili PL, Massaro G, Elisei F, Ortica F. 2014. A triplet-triplet annihilation based up-conversion process investigated in homogeneous solutions and oil-in-water microemulsions of a surfactant. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 13, 48–61. ( 10.1039/c3pp50318f) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Islangulov RR, Castellano FN. 2006. Photochemical upconversion: anthracene dimerization sensitized to visible light by a Ru-II chromophore. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 45, 5957–5959. ( 10.1002/anie.200601615) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Khnayzer RS, Blumhoff J, Harrington JA, Haefele A, Deng F, Castellano FN. 2012. Upconversion-powered photoelectrochemistry. Chem. Commun. 48, 209–211. ( 10.1039/C1CC16015J) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Monguzzi A, Bianchi F, Bianchi A, Mauri M, Simonutti R, Ruffo R, Tubino R, Meinardi F. 2013. High efficiency up-converting single phase elastomers for photon managing applications. Adv. Energy Mater. 3, 680–686. ( 10.1002/aenm.201200897) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cheng YY, Khoury T, Clady RGCR, Tayebjee MJY, Ekins-Daukes NJ, Crossley MJ, Schmidt TW. 2010. On the efficiency limit of triplet–triplet annihilation for photochemical upconversion. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 12, 66–71. ( 10.1039/B913243K) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cheng YY, Fückel B, Khoury T, Clady RGCR, Tayebjee MJY, Ekins-Daukes NJ, Crossley MJ, Schmidt TW. 2010. Kinetic analysis of photochemical upconversion by triplet-triplet annihilation: beyond any spin statistical limit. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 1, 1795–1799. ( 10.1021/jz100566u) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Deng F, Blumhoff J, Castellano FN. 2013. Annihilation limit of a visible-to-UV photon upconversion composition ascertained from transient absorption kinetics. J. Phys. Chem. A 117, 4412–4419. ( 10.1021/jp4022618) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schmidt TW, Castellano FN. 2014. Photochemical upconversion: the primacy of kinetics. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 5, 4062–4072. ( 10.1021/jz501799m) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cheng YY, Fückel B, Khoury T, Clady RGCR, Ekins-Daukes NJ, Crossley MJ, Schmidt TW. 2011. Entropically driven photochemical upconversion. J. Phys. Chem. A 115, 1047–1053. ( 10.1021/jp108839g) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Singh-Rachford TN, Castellano FN. 2010. Photon upconversion based on sensitized triplet–triplet annihilation. Coord. Chem. Rev. 254, 2560–2573. ( 10.1016/j.ccr.2010.01.003) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ceroni P. 2011. Energy up-conversion by low-power excitation: new applications of an old concept. Chem. Eur. J. 17, 9560–9564. ( 10.1002/chem.201101102) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Islangulov RR, Kozlov DV, Castellano FN. 2005. Low power upconversion using MLCT sensitizers. Chem. Commun. 2005, 3776–3778. ( 10.1039/b506575e) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kozlov DV, Castellano FN. 2004. Anti-Stokes delayed fluorescence from metal-organic bichromophores. Chem. Commun. 2004, 2860–2861. ( 10.1039/b412681e) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Singh-Rachford TN, Castellano FN. 2010. Triplet sensitized red-to-blue photon upconversion. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 1, 195–200. ( 10.1021/jz900170m) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wu W, Guo H, Ji S, Zhao J. 2011. Organic triplet sensitizer library derived from a single chromophore (BODIPY) with long-lived triplet excited state for triplet–triplet annihilation based upconversion. J. Org. Chem. 76, 7056–7064. ( 10.1021/jo200990y) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kim J-H, Deng F, Castellano FN, Kim J-H. 2014. Red-to-blue/cyan/green upconverting microcapsules for aqueous- and dry-phase color tuning and magnetic sorting. ACS Photonics 1, 382–388. ( 10.1021/ph500036m) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McCusker CE, Castellano FN. 2013. Orange-to-blue and red-to-green photon upconversion with a broadband absorbing copper(I) MLCT sensitizer. Chem. Commun. 49, 3537–3539. ( 10.1039/c3cc40778k) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Islangulov RR, Lott J, Weder C, Castellano FN. 2007. Noncoherent low-power upconversion in solid polymer films. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 129, 12652–12653. ( 10.1021/ja075014k) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Monguzzi A, Tubino R, Meinardi F. 2009. Multicomponent polymeric film for red to green low power sensitized up-conversion. J. Phys. Chem. A 113, 1171–1174. ( 10.1021/jp809971u) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kim J-H, Deng F, Castellano FN, Kim J-H. 2012. High efficiency low-power upconverting soft materials. Chem. Mater. 24, 2250–2252. ( 10.1021/cm3012414) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Svagan AJ, Busko D, Avlasevich Y, Glasser G, Baluschev S, Landfester K. 2014. Photon energy upconverting nanopaper: a bioinspired oxygen protection strategy. ACS Nano 8, 8198–8207. ( 10.1021/nn502496a) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Duan P, Yanai N, Nagatomi H, Kimizuka N. 2015. Photon upconversion in supramolecular gel matrixes: spontaneous accumulation of light-harvesting donor–acceptor arrays in nanofibers and acquired air stability. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 137, 1887–1894. ( 10.1021/ja511061h) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Keivanidis PE, Baluschev S, Miteva T, Nelles G, Scherf U, Yasuda A, Wegner G. 2003. Up-conversion photoluminescence in polyfluorene doped with metal(II)–octaethyl porphyrins. Adv. Mater. 15, 2095–2098. ( 10.1002/adma.200305717) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Baluschev S, Keivanidis PE, Wegner G, Jacob J, Grimsdale AC, Müllen K, Miteva T, Yasuda A, Nelles G. 2005. Upconversion photoluminescence in poly(ladder-type-pentaphenylene) doped with metal (II)-octaethyl porphyrins. Appl. Phys. Lett. 86, 061904 ( 10.1063/1.1857073) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Baluschev S, et al. 2005. Enhanced operational stability of the up-conversion fluorescence in films of palladium-porphyrin end-capped poly(pentaphenylene). Chemphyschem 6, 1250–1253. ( 10.1002/cphc.200500098) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Poorkazem K, Hesketh AV, Kelly TL. 2014. Plasmon-enhanced triplet–triplet annihilation using silver nanoplates. J. Phys. Chem. C 118, 6398–6404. ( 10.1021/jp412223m) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Marsico F, et al. 2014. Hyperbranched unsaturated polyphosphates as a protective matrix for long-term photon upconversion in air. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136, 11057–11064. ( 10.1021/ja5049412) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mezyk J, Tubino R, Monguzzi A, Mech A, Meinardi F. 2009. Effect of an external magnetic field on the up-conversion photoluminescence of organic films: the role of disorder in triplet-triplet annihilation. Phys. Rev. Lett. 102, 087404 ( 10.1103/PhysRevLett.102.087404) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schulze TF, Schmidt TW. 2015. Photochemical upconversion: present status and prospects for its application to solar energy conversion. Energy Environ. Sci. 8, 103–125. ( 10.1039/C4EE02481H) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gray V, Dzebo D, Abrahamsson M, Albinsson B, Moth-Poulsen K. 2014. Triplet-triplet annihilation photon-upconversion: towards solar energy applications. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 16, 10345–10352. ( 10.1039/c4cp00744a) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Auckett JE, Chen YY, Khoury T, Clady RGCR, Ekins-Daukes NJ, Crossley MJ, Schmidt TW. 2009. Efficient up-conversion by triplet-triplet annihilation. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 185, 012002 ( 10.1088/1742-6596/185/1/012002) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Deng F, Sommer JR, Myahkostupov M, Schanze KS, Castellano FN. 2013. Near-IR phosphorescent metalloporphyrin as a photochemical upconversion sensitizer. Chem. Commun. 49, 7406–7408. ( 10.1039/C3CC44479A) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Singh-Rachford TN, Castellano FN. 2008. Pd(II) phthalocyanine-sensitized triplet-triplet annihilation from rubrene. J. Phys. Chem. A 112, 3550–3556. ( 10.1021/jp7111878) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Singh-Rachford TN, Nayak A, Muro-Small ML, Goeb S, Therien MJ, Castellano FN. 2010. Supermolecular-chromophore-sensitized near-infrared-to-visible photon upconversion. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 132, 14203–14211. ( 10.1021/ja105510k) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Deng F, Sun W, Castellano FN. 2014. Texaphyrin sensitized near-IR-to-visible photon upconversion. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 13, 813–819. ( 10.1039/C4PP00037D) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yakutkin V, Aleshchenkov S, Chernov S, Miteva T, Nelles G, Cheprakov A, Baluschev S. 2008. Towards the IR limit of the triplet-triplet annihilation-supported up-conversion: tetraanthraporphyrin. Chem. Eur. J. 14, 9846–9850. ( 10.1002/chem.200801305) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.MacQueen RW, Cheng YY, Danos AN, Lips K, Schmidt TW. 2014. Action spectrum experiment for the measurement of incoherent photon upconversion efficiency under sun-like excitation. RSC Adv. 4, 52749–52756. ( 10.1039/C4RA08706B) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sripathy K, MacQueen RW, Peterson JR, Cheng YY, DvoŖák M, McCamey DR, Treat ND, Stingelin N, Schmidt TW. 2015. Highly efficient photochemical upconversion in a quasi-solid organogel. J. Mater. Chem. C 3, 616–622. ( 10.1039/C4TC02584A) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tyson DS, Bialecki J, Castellano FN. 2000. Ruthenium(II) complex with a notably long excited state lifetime. Chem. Commun. 2000, 2355–2356. ( 10.1039/B007336I) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Castellano FN. 2012. Transition metal complexes meet the rylenes. Dalton Trans. 41, 8493 ( 10.1039/c2dt30765k) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ji S, Wu W, Guo H, Zhao J. 2011. Ruthenium(II) polyimine complexes with a long-lived 3IL excited state or a 3MLCT/IL equilibrium: efficient triplet sensitizers for low-power upconversion. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 50, 1626–1629. ( 10.1002/anie.201006192) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tyson DS, Henbest KB, Bialecki J, Castellano FN. 2001. Excited state processes in ruthenium(II)/pyrenyl complexes displaying extended lifetimes. J. Phys. Chem. A 105, 8154–8161. ( 10.1021/jp011770f) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kozlov DV, Tyson DS, Goze C, Ziessel R, Castellano FN. 2004. Room temperature phosphorescence from ruthenium(II) complexes bearing conjugated pyrenylethynylene subunits. Inorg. Chem. 43, 6083–6092. ( 10.1021/ic049288+) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Montalti M, Credi A, Prodi L, Gandolfi MT. 2006. Handbook of photochemistry, 3rd edn Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Haefele A, Blumhoff J, Khnayzer RS, Castellano FN. 2012. Getting to the (square) root of the problem: how to make noncoherent pumped upconversion linear. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 3, 299–303. ( 10.1021/jz300012u) [DOI] [Google Scholar]