Abstract

The segmental architecture of the arthropod head is one of the most controversial topics in the evolutionary developmental biology of arthropods. The deutocerebral (second) segment of the head is putatively homologous across Arthropoda, as inferred from the segmental distribution of the tripartite brain and the absence of Hox gene expression of this anterior-most, appendage-bearing segment. While this homology statement implies a putative common mechanism for differentiation of deutocerebral appendages across arthropods, experimental data for deutocerebral appendage fate specification are limited to winged insects. Mandibulates (hexapods, crustaceans and myriapods) bear a characteristic pair of antennae on the deutocerebral segment, whereas chelicerates (e.g. spiders, scorpions, harvestmen) bear the eponymous chelicerae. In such hexapods as the fruit fly, Drosophila melanogaster, and the cricket, Gryllus bimaculatus, cephalic appendages are differentiated from the thoracic appendages (legs) by the activity of the appendage patterning gene homothorax (hth). Here we show that embryonic RNA interference against hth in the harvestman Phalangium opilio results in homeonotic chelicera-to-leg transformations, and also in some cases pedipalp-to-leg transformations. In more strongly affected embryos, adjacent appendages undergo fusion and/or truncation, and legs display proximal defects, suggesting conservation of additional functions of hth in patterning the antero-posterior and proximo-distal appendage axes. Expression signal of anterior Hox genes labial, proboscipedia and Deformed is diminished, but not absent, in hth RNAi embryos, consistent with results previously obtained with the insect G. bimaculatus. Our results substantiate a deep homology across arthropods of the mechanism whereby cephalic appendages are differentiated from locomotory appendages.

Keywords: Arthropoda, deutocerebrum, antenna, chelicera, opiliones, serial homology

1. Introduction

One of the defining hallmarks of arthropod diversity is morphological disparity of the appendages. The diversification of arthropod appendages has transformed the evolutionary adaptive landscape for Arthropoda, unlocking access to various ecological opportunities and environments [1,2]. The fossil record and phylogeny of Arthropoda indicate that by the Early Cambrian, crown-group arthropods bore a division between cephalic, or ‘head’, appendages, and polyramous locomotory appendages on a homonomous ‘trunk’. This division between cephalic and locomotory appendage-bearing segments is observed in such iconic Palaeozoic linages as trilobites and ‘great-appendage’ arthropods (e.g. Anomalocaris), as well as Onychophora, the sister group of Arthropoda [3,4].

The segmental correspondence of anterior appendages, the ganglia of the arthropod tripartite brain and the anterior tagma has long been disputed [3,5–8]. A general consensus has formed that the first appendage-bearing segments of Mandibulata and Chelicerata are homologous, based both on the innervation of these appendages by the deutocerebral ganglia (the second part of the tripartite arthropod brain), and on the absence of Hox gene expression in the deutocerebral segment across arthropods [6,7,9–11]. Implicit in this homology statement is the homology of the deutocerebral appendages, which are markedly different in both morphology and function between mandibulates and chelicerates. The deutocerebral appendage of mandibulates (hexapods, crustaceans and myriapods) is invariably an antenna, which is typically elongate, composed of numerous segments (‘antennomeres’) and dedicated to sensory function. By contrast, the deutocerebral appendage of chelicerates (pycnogonids, horseshoe crabs and arachnids) is the chelicera or chelifore, a short appendage consisting of two to four segments and involved in feeding. Whereas the correspondence of arthropod head segments has a basis in neuroanatomical and developmental genetic evidence [6–11], the correspondence of antennae and chelicerae remains unsubstantiated.

The best understood case of deutocerebral appendage fate specification is that of antennae in the fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster (figure 1). The Hox gene Antennapedia (Antp) is required for leg identity in the thorax, where Antp represses expression of the TALE-class gene homothorax (hth). This repression ensures that expression of hth in the outer margin of the developing leg discs (which patterns proximal podomeres [leg segments]) has minimal overlap with that of Distal-less (Dll, which patterns distal podomeres); the proximally restricted co-expression of hth and its cofactor extradenticle (exd) functions to pattern proximal podomeres. Knockdown of Antp (or alternatively, ectopic expression of hth in the legs) results in leg-to-antenna transformation in the thorax [12–17]. Inversely, ectopic expression of Antp in the antennal disc, where it is normally not expressed (or alternatively, knockdown of antennal hth expression) causes antenna-to-leg transformations [15–17]. The repressive interaction between hth and Antp has been presumed to be direct (but see [18]). In addition, the selector gene spineless (ss), which acts downstream of Antp, Dll and hth/exd, confers distal antennal identity in the antenna (figure 1). In two holometabolous insect orders (D. melanogaster and four species of the beetle genus Tribolium), antennal ss expression arises within the Dll domain upon co-activation by hth/exd and Dll. At later stages, ss represses expression of hth in the distal tip of the antenna [14,19–21]. It has also been demonstrated that Antp represses ss in the legs directly, by competing with Dll for binding of the ss enhancer [18].

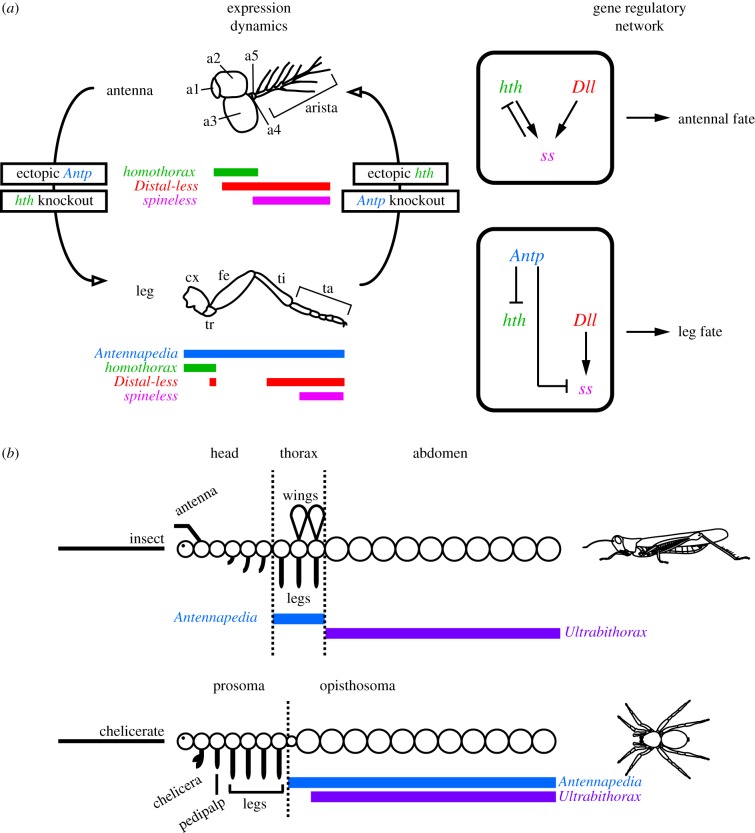

Figure 1.

Developmental dynamics of hth expression in deutocerebral and locomotory appendages. (a) Expression domains of Antp, hth, Dll and ss in the antenna and walking leg of D. melanogaster. In the antenna, hth knockdown or Antp overexpression results in antenna-to-leg transformation. In the leg, hth overexpression or Antp knockdown results in leg-to-antenna transformation. Gene interactions are shown to the right. (b) Comparative gene expression patterns of the Hox genes Antp and Ubx in an archetypal insect and arachnid. Note that chelicerate Antp is not expressed in the leg-bearing segments. (Online version in colour.)

The similarity of the loss-of-function phenotypes of both hth and its cofactor extradenticle (exd) indicates that the Hox-binding Hth/Exd heterodimer fulfils multiple roles during patterning of both body and appendage axes [15,16,22]. Loss-of-function mutants of both hth and exd display: (i) segmentation defects along the antero-posterior axis of the body; (ii) proximal defects along the proximo-distal axis of appendages; and (iii) antenna-to-leg transformations.

Elements of the fruit fly-based antennal specification model (figure 1a) have been validated in three other insects [23–26]. Intriguingly, RNAi-mediated knockdown of hth in the cricket Gryllus bimaculatus causes all cephalic appendages, not just antennae, to transform towards leg identity [26]. Barring insects, functional data for arthropod hth are unavailable for all other lineages in the arthropod tree of life.

In Chelicerata, the sister group to the remaining Arthropoda, gene expression data for the Antp orthologue demonstrate conserved expression throughout the posterior tagma (opisthosoma) of multiple surveyed species, but absence from the leg-bearing prosoma [9,27–29], suggesting that chelicerate Antp is not involved in appendage identity specification (figure 1b). Concordantly, functional data have demonstrated that the spider Antp orthologue represses limb development in the opisthosoma of Parasteatoda tepidariorum [30]. By contrast, expression dynamics of hth are more comparable to insect counterparts. In chelicerates, hth is expressed throughout the developing limb buds in early stages of embryonic development, but retracts from the distal-most parts of the appendages in later stages [31,32], as in the antennal disc of D. melanogaster [15,16] (figure 2). In late states of chelicerate development, the degree of overlap between hth and Dll expression domains is unique to each appendage type [31,32]. As in D. melanogaster, this overlap is nearly complete in the deutocerebral appendages, but not in the walking legs, where hth is absent from the two distal-most podomeres [31–33] (figure 2).

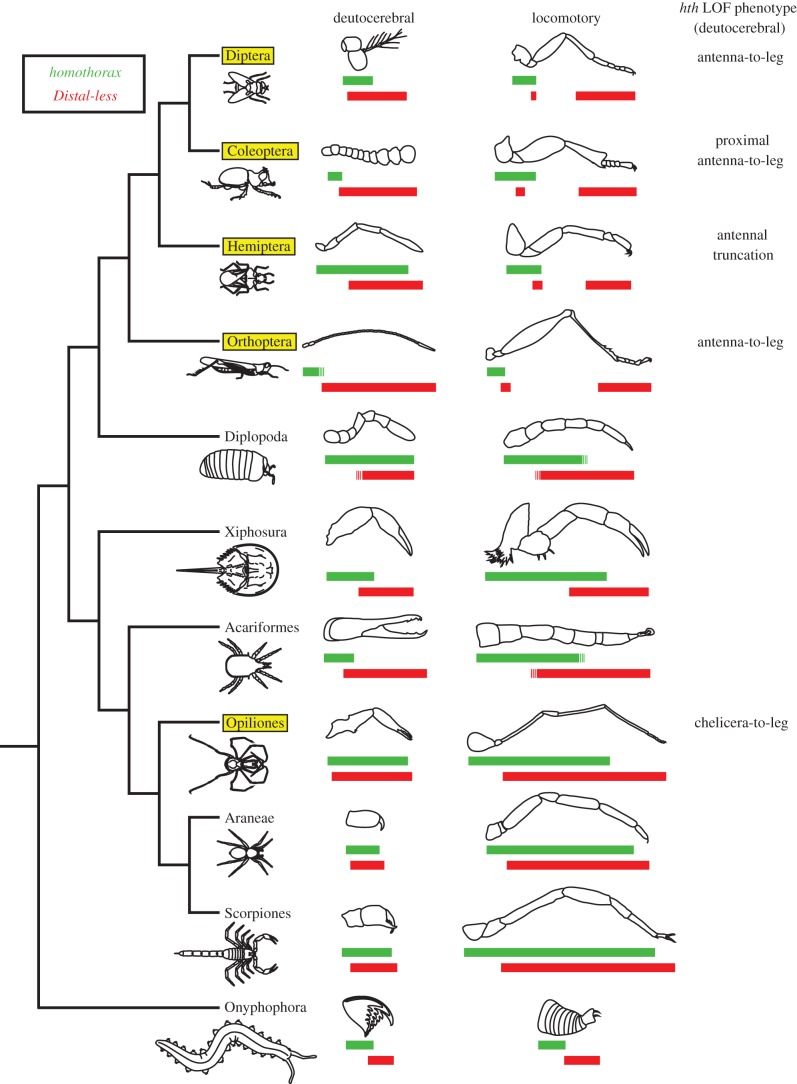

Figure 2.

Reported expression boundaries of hth (green; upper bar) and Dll (red; lower bar) for deutocerebral and walking leg appendages across Arthropoda. Broken lines indicate uncertainty of expression boundary with respect to specific podomeres. Boxed orders indicate availability of functional data for hth orthologues (including from this study). References provided in the electronic supplementary material. (Online version in colour.)

This similarity of expression dynamics suggests that chelicerate hth has a function in specifying appendage identity. Therefore, we investigated the function of hth in the harvestman Phalangium opilio. We hypothesized that if patterning of the antenna and chelicera is homologous, then knockdown of Po-hth should result in a chelicera-to-leg homeotic transformation (as observed for insect hth knockdowns [13,16,19,24,26]). In support of this hypothesis, here we show that RNAi-mediated knockdown of the single-copy hth orthologue of P. opilio results in the same range of hth loss-of-function phenotypes observed in insects, and specifically includes homeotic transformation of chelicerae and pedipalps towards leg identity. These data indicate that the mechanism of deutocerebral appendage fate specification is conserved in Chelicerata, and by extension, putatively across Arthropoda.

2. Material and methods

(a). Animal cultivation and gene cloning

Embryos of wild caught P. opilio and Centruroides sculpturatus were obtained as described previously [29,34]. Embryos of Limulus polyphemus were kindly provided by B. Battelle and H. J. Brockmann (Department of Biology, University of Florida) and were staged according to [35]. Isolation of the P. opilio hth fragment from a developmental transcriptome was previously reported [36]. We similarly isolated hth and Dll orthologues of C. sculpturatus from its corresponding developmental transcriptome [34]. Both fragments were cloned and Sanger sequenced for verification of transcriptomic assembly. PCR products were cloned using the TOPO® TA Cloning® Kit with One Shot® Top10 chemically competent Escherichia coli (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA), following the manufacturer's protocol, and their identities verified by sequencing. Two non-overlapping Po-hth fragments of approximately similar size (286 bp and 299 bp) were separately amplified and cloned using internal primer pairs.

The hth orthologue from L. polyphemus was identified from NCBI expressed sequence tags databases using tblastx. Primers were designed to amplify an approximately 500 bp fragment that was then cloned by RT-PCR using cDNA from stage 19 to 20 embryos and Sanger sequenced to verify identity.

All primer sequences are provided in the electronic supplementary material, table S2. All verified hth sequences were accessioned in GenBank (KP129111–129113).

(b). Fixation and whole mount in situ hybridization of chelicerate embryos

Whole mount in situ hybridization was performed as previously described for P. opilio [28], C. sculpturatus [34] and L. polyphemus [37]. Riboprobe synthesis for hth and Hox genes also followed the respective published protocols. Embryos were mounted in glycerol and images were captured using an HrC AxioCam and an Axio Zoom V.16 fluorescence stereomicroscope driven by Zen (Zeiss).

(c). Double stranded RNA synthesis

Double stranded RNA (dsRNA) was synthesized with the MEGAscript® T7 kit (Ambion/Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY, USA) from amplified PCR product (above), following the manufacturer's protocol. The synthesis was conducted for 4 h, followed by a 5 min cool-down step to room temperature. A LiCl precipitation step was conducted, following the manufacturer's protocol. dsRNA quality and concentration were checked using a Nanodrop-1000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific, Wilmington, DE, USA) and the concentration of the dsRNA was subsequently adjusted to 3.75–4.00 mg ml−1.

(d). Embryonic RNAinterference

Embryos of P. opilio were collected from wild caught females maintained in the laboratory. Embryos were dechorionated, dehydrated for 30 min and mounted on glass coverslips as described previously [38]. Eggs from each P. opilio clutch were randomly divided into control (20–30% of individuals) and hth-dsRNA injection treatments (70–80% of individuals).

As controls, 161 embryos were injected with exogenous dsRNA (a 678 bp fragment of DsRed) following a published protocol [38]. Animals were subsequently scored as wild-type (normal development), or as dead/indeterminate (‘indeterminate’ indicates failure to complete development after six weeks post-injection and is typically accompanied by abnormal development at the site of injection). Results of injections are shown in the electronic supplementary material, figure S1 and table S1.

Another 256 embryos were injected with a 768 bp fragment of hth-dsRNA. Resulting embryos were classified into wild-type, dead/indeterminate, Class I (strong) phenotype (animals with defects in neurogenesis, anteroposterior (AP) segmentation, truncated appendages and severe proximal leg defects) and Class II (weak) phenotype (animals with proximal leg defects, homeotic transformation of gnathal appendages to legs or non-chelate chelicerae without homeotic transformation).

To exclude off-target effects caused by dsRNA injection, two additional and non-overlapping fragments of Po-hth (248 bp and 259 bp) were injected independently into 95 embryos each (electronic supplementary material, figure S1). Resulting embryos were classified the same way.

3. Results and discussion

(a). Podomeric boundaries of homothorax expression are conserved in Arachnida

Patterns of gene expression in Mandibulata have revealed that the proximal boundary of hth expression is variable in the deutocerebral antenna. Despite functional correspondence with D. melanogaster and P. opilio hth orthologues, hth expression in the cricket G. bimaculatus is proximally restricted in the antenna [26], whereas hth expression in the hemipteran Oncopeltus fasciatus spans nearly all of its antenna [24] (figure 2). Therefore, to infer whether any putative role of hth identified in P. opilio is generalizable to other members of Chelicerata, we took two approaches. First, we surveyed the literature for known expression patterns of hth in chelicerates (e.g. spiders; [32,33]). Second, we generated novel hth expression data for the chelicerates C. sculpturatus (scorpion) and L. polyphemus (horseshoe crab).

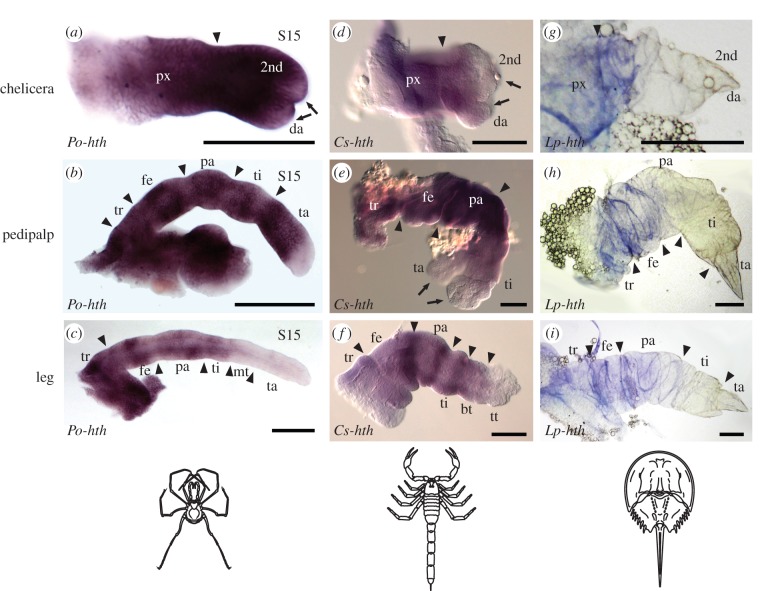

Our in situ hybridization experiments revealed that in contrast to mandibulates, distal expression boundaries of all arachnid hth orthologues examined were similar in stages wherein podomeres are recognizable (figure 3). Nearly ubiquitous and strong expression of hth occurred in chelicerae of Arachnida, except in the distal-most parts of the chela. In posterior appendages, hth expression domains also occurred broadly throughout the appendage, as in P. opilio. By contrast, hth expression in L. polyphemus extended only to the proximal part of the secondary article of the chelicerae, and the proximal part of the tibia of posterior appendages (figure 3). This difference may be attributable to stage incompatibilities between L. polyphemus and the arachnids, as horseshoe crabs undergo a series of embryonic moults with concomitant saltational morphogenesis that is not observed in Arachnida [35]. Absence of (or weaker) hth expression was observed in the distal tips of all chelate appendages, suggesting that the chela constitutes a distal bifurcation of the proximodistal (PD) axis throughout Chelicerata.

Figure 3.

hth expression patterns in embryonic appendages of (a–c) the harvestman, P. opilio; (d–f) the scorpion, C. sculpturatus; and (g–i) the horseshoe crab, L. polyphemus. Arrowheads indicate segmental boundaries. Note absence of hth expression from both termini of all chelate appendages (arrows). Expression data for multiple spider species are closely comparable with harvestman counterparts and are not shown (figure 2). Scale bars, 100 µm. bt, basitarsus; da, distal article; fe, femur; mt, metatarsus; pa, patella; px, proximal segment; ta, tarsus; ti, tibia; tr, trochanter; tt, telotarsus. Expression data for Dll of C. sculpturatus are provided as the electronic supplementary material, figure S4. (Online version in colour.)

Based upon the data presented here, taken together with reported expression patterns in the millipede Glomeris marginata and multiple spider species [32,33], we infer that broad expression of hth and Dll in both proximal and distal territories of deutocerebral appendages was present in the arthropod common ancestor. The ancestral state of gene expression in the common ancestor of Panarthropoda remains ambiguous, as hth and Dll expression in the unsegmented deutocerebral appendage (jaw) of Onychophora is different from that of basal arthropods (figure 2).

(b). A conserved pleiotropic spectrum of homothorax phenotypes in insects and Phalangium opilio

In situ hybridizations for hth on embryos with strong hth loss-of-function phenotypes showed decreased hth expression in wild-type domains (electronic supplementary material, figure S2), confirming effective RNAi-mediated knockdown of hth expression. Of the 202 embryos surviving injection of hth-dsRNA, 22% (n = 45), displayed developmental defects including antero-posterior segmental fusions in the prosoma, proximal leg defects and/or homeotic transformation of gnathal appendages. We classified embryos with antero-posterior segmental fusions and/or whole-appendage truncations as Class I (strong) phenotypes (n = 21), and embryos with proximal leg defects and/or homeotically transformed appendages as Class II (weak) phenotypes (n = 24). Mosaic phenotypes, wherein loss-of-function defects were observed principally in only one-half of the embryo, occurred in 43% of Class I (n = 9) and 100% of Class II (n = 24) phenotypes. This range of phenotypes was observed upon injection of a 768 bp fragment of hth-dsRNA, and either of two non-overlapping fragments amplified from the same Po-hth clone (248 and 259 bp; electronic supplementary material, table S1 and figure S1), confirming specificity of these hth knockdown phenotypes.

Embryos with Class I phenotypes (electronic supplementary material, figure S2) did not survive to hatching. Head patterning defects included partial or complete loss of the head lobe. Embryos in this phenotype class displayed fusions of adjacent segments along the AP axis, typically the cheliceral and pedipalpal segments. The labrum and/or some appendages also failed to form. When present, appendages were fused or showed proximal patterning defects, with proximal podomeres and endites failing to form (electronic supplementary material, figure S2). We interpret these phenotypes to be highly comparable with the AP segmentation defects and PD proximal patterning defects observed upon knockdown of hth in insects [24,26].

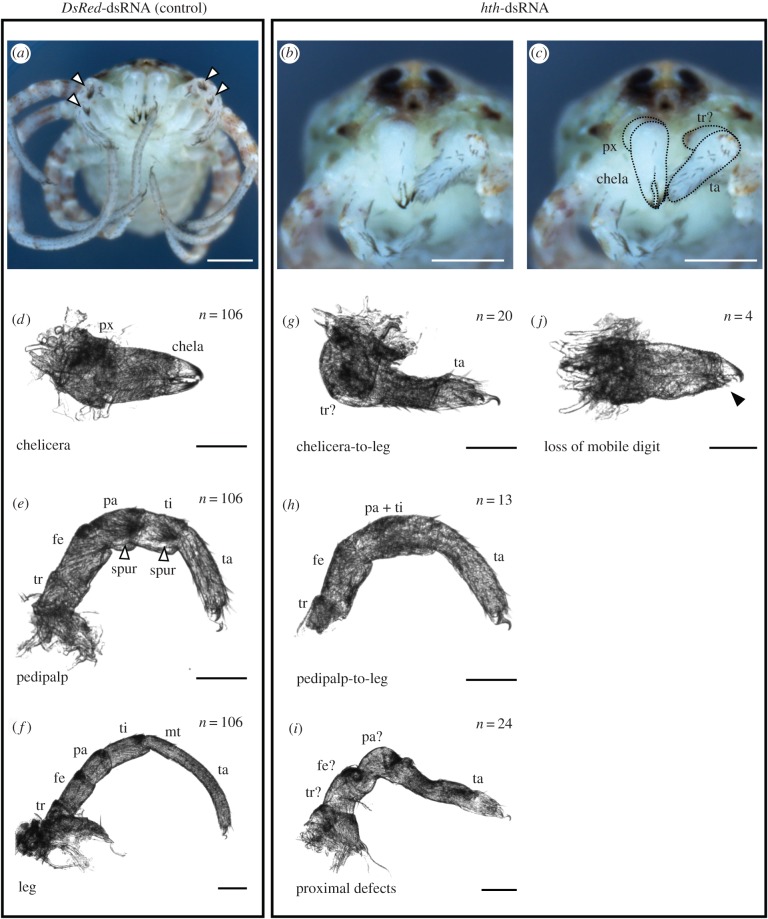

In contrast to all Class I phenotype embryos, some mosaic Class II phenotype embryos (figure 4) survived to hatching, enabling morphological corroboration of homeosis. In some embryos with Class II phenotypes (n = 7), a tarsus-like structure with a single terminal claw and leg-like setation patterns formed in place of the chela, indicating homeotic transformation to leg identity (figure 4g). In embryos with more severe Class II phenotypes (n = 13), distal elements of both chelicera and pedipalp were transformed towards leg-like identity, as inferred from podomeres with leg-like setation patterns and absence of pedipalpal spurs (figure 4h).

Figure 4.

Knockdown of hth results in homeotic transformations of gnathal appendages to legs in a chelicerate (Class II phenotype). (a) Control-injected hatchling of P. opilio, demonstrating wild-type morphology (ventral view). White arrowheads indicate pedipalpal spurs, which distinguish these appendages. (b,c) hth-dsRNA-injected hatchling of P. opilio in ventral view, exhibiting homeotic chelicera-to-leg transformation on one side (animal's left). (c) Same figure as in (b), with deutocerebral appendages outlined for clarity. (d–f) Appendage mounts of control-injected hatchlings. White arrowheads in (e) indicate pedipalpal spurs. (g–j) Appendage mounts of hth-dsRNA-injected hatchlings. Homeotic chelicera-to-leg transformation (g) and pedipalp-to-leg transformation (h) are accompanied by proximal leg defects (i). Note absence of pedipalpal spurs in (h). (j) Loss of mobile digit in a chelicera (black arrowhead). Scale bar for (a–c): 200 µm. Scale bar for (d–j): 50 µm. Abbreviations as in figure 3. (Online version in colour.)

The harvestman hth knockdown appendage phenotypes described above are remarkably similar to those observed in insects. Among hemimetabolous insects, in the cricket G. bimaculatus, parental RNAi-mediated knockdown of hth resulted in similar transformation of all cephalic appendages towards leg identity in some embryos, and comparable fusion of adjacent segments in stronger phenotypes [26]. In parental RNAi experiments with the milkweed bug O. fasciatus, weaker hth phenotypes consisted of distal labium (second maxilla)-to-leg transformations, and truncation of antennae [24]. The similar range of phenotypes observed upon knockdown of hth orthologues in multiple insects and the chelicerate exemplar P. opilio suggests evolutionary conservation of hth function in proximo-distal patterning and cephalic appendage specification over 550 million years of arthropod evolution. The implicit serial homology of antennae and chelicerae is consistent with transitional morphologies observed in the fossil record, such as the antenniform chelicerae of the Silurian synziphosurines Dibasterium durgae and Offacolus kingi [39,40]. The unique deutocerebral appendages of these stem-horseshoe crabs elude facile characterization, as they are interpreted to bear a large number of articulated segments (typical of antennae) and also a distal chela composed of two segments (typical of chelicerae). Similar comparisons have also been made between modern chelicerae and a series of ‘great-appendage’ arthropod fossils [8,41], and particularly so for the reconstructed deutocerebral appendages of leanchoiliids that exemplify the intermediate condition of chelicerae (three distal axes, dentition) and antennae (three flagella with numerous antennules) [42]. Taken together with the absence of Hox gene expression in the deutocerebral segment of all surveyed panarthropods [6,10,43], as well as the conservation of hth function in insects and a chelicerate (this study), the existence of such transitional morphologies in the fossil record suggests that different aspects of the ancestral deutocerebral appendage were retained by the mandibulate and chelicerate lineages. The morphological distinction between antenna and chelicera may thus result from differential losses of downstream targets of hth that occurred in a lineage-specific manner. The role of ss as one such downstream target of hth is currently under investigation in chelicerates (P. P. Sharma, W. C. Wheeler and C. G. Extavour 2015, personal communication).

With respect to conservation of gene interaction, knockdown of the hth cofactor exd in G. bimaculatus results in similar homeotic transformation of gnathal appendages towards leg identity, with accompanying loss of gnathal Hox gene expression (Deformed and Sex combs reduced; [25]). The similar phenotypes resulting from knockdown of either hth or exd reflect the requirement of Hth for transport of Exd to the nucleus, and the instability of Hth in the absence of Exd [22,44]. However, knockdown of hth in G. bimaculatus does not eliminate anterior Hox gene expression, in contrast to knockdown of exd in the same species [25,26]. Comparably, we observed diminished, but not eliminated, expression of the Hox genes labial, proboscipedia, or Deformed in Class I P. opilio embryos (electronic supplementary material, figure S3).

This finding is suggestive of a conserved, if poorly understood, mechanism whereby hth interacts with Hox genes, such that cephalic appendage identities are specified by varying hth expression, as determined by Hox input [26]. Indeed, Hth and Exd are bona fide Hox cofactors in D. melanogaster [22,44–46]. However, functional data for chelicerate Hox genes are limited to analysis of Antp, and thus the interaction of hth and anterior Hox genes is unknown for chelicerates [30]. In addition, Antp in the spider P. tepidariorum appears to have a function that is convergent upon the role of Ultrabithorax in insects (i.e. repressing appendage formation), suggesting that Hox function in appendage-bearing segments of mandibulates and chelicerates is not directly comparable (figure 1). An alternative interpretation of the cricket and harvestman data may also be that hth RNAi phenotypes are generally weaker than exd RNAi phenotypes, and that eliminating hth expression would result in loss of Hox expression in both species [26].

(c). A possible role for homothorax in patterning terminal chelae

An outstanding question regarding the evolution of the arthropod appendage is the mechanism whereby chelate appendages acquired a chela, i.e. a distal bifurcation of the PD axis. In the spectrum of hth knockdown phenotypes in P. opilio, we observed that in the weakest of the Class II phenotypes (n = 4), the chelicerae retained dentition and cheliceral setation (i.e. retained cheliceral identity), but the mobile digit (i.e. distal article) was reduced (figure 4j). In the P. opilio chela, the mobile digit is the smaller of two distal buds that strongly expresses hth prior to segmentation.

One possible mechanism for the bifurcation of the distal cheliceral limb bud is recruitment of hth itself for patterning this secondary axis. Overexpression of hth in D. melanogaster results in just such a duplication of the antennal axis at the a3 segment [47]. Together with similar expression patterns of hth in other chelate appendage termini, these data suggest a common mechanism whereby chelae are formed in various arthropod appendages. Beyond RNAi approaches in scorpions (chelate chelicerae and pedipalps), horseshoe crabs (all prosomal appendages chelate) or such mandibulates as pauropods (bifurcating antennae), this hypothesis could also be tested in future through misexpression of hth in non-chelate appendages of emerging model chelicerates like the spider P. tepidariorum, with the prediction that ectopic hth expression would cause distal axis duplication in the pedipalps and legs (as in D. melanogaster). At present, such functional tools are presently not available for chelicerates, being limited to RNAi in spiders, mites and harvestmen.

4. Conclusion

Our results reveal an ancestral mechanism whereby cephalic and locomotory appendages are differentiated in arthropods. RNAi-mediated gene knockdown of a chelicerate hth orthologue demonstrates extraordinary conservation of multiple functions, including specification of gnathal appendage identity and proximo-distal axial patterning. The transformation of both the antenna and the chelicera towards leg identity upon knockdown of hth, together with the absence of any Hox gene expression in their respective segments, is consistent with the serial homology of deutocerebral appendages. Future investigations should emphasize identification of lineage-specific (i.e. antennal versus cheliceral) deutocerebral selector genes, towards testing the hypothesis that variation in deutocerebral appendage morphology is attributable to evolution in the downstream targets of hth.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

Douglas Richardson facilitated imaging at the Harvard Center for Biological Imaging. Discussions with David R. Angelini, Frank W. Smith and Gonzalo Giribet refined some of the ideas presented in this study. Comments from Associate Editor Philip Donoghue and two anonymous reviewers improved an earlier draft of the manuscript.

Funding statement

This work was partially supported by NSF grant no. IOS-1257217 to C.G.E. and AMNH funds to W.W. P.P.S. was supported by the National Science Foundation Postdoctoral Research Fellowship in Biology under grant no. DBI-1202751.

Authors' contributions

P.P.S. conceived of the project, designed the study, collected arachnid data and wrote the manuscript. P.P.S. and E.E.S. jointly analysed RNAi data. O.A.T. and D.H.L. collected horseshoe crab data. M.J.C., W.C.W. and C.G.E. provided resources and funding for various parts of the study. All authors edited the manuscript and approved the final content.

References

- 1.Snodgrass RE. 1938. Evolution of the Annelida, Onychophora and Arthropoda. Smithson. Misc. Coll. 97, 1–159. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boxshall GA. 2004. The evolution of arthropod limbs. Biol. Rev. 79, 253–300. ( 10.1017/S1464793103006274) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Budd GE. 2002. A palaeontological solution to the arthropod head problem. Nature 417, 271–275. ( 10.1038/417271a) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Waloszek D, Chen J, Maas A, Wang X. 2005. Early Cambrian arthropods: new insights into arthropod head and structural evolution. Arthropod Struct. Dev. 34, 189–205. ( 10.1016/j.asd.2005.01.005) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Maxmen A, Browne WE, Martindale MQ, Giribet G. 2005. Neuroanatomy of sea spiders implies an appendicular origin of the protocerebral segment. Nature 437, 1144–1148. ( 10.1038/nature03984) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jager M, Murienne J, Clabaut C, Deutsch J, Le Guyader H, Manuel M. 2006. Homology of arthropod anterior appendages revealed by Hox gene expression in a sea spider. Nature 441, 506–508. ( 10.1038/nature04591) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Scholtz G, Edgecombe GD. 2006. The evolution of arthropod heads: reconciling morphological, developmental and palaeontological evidence. Dev. Genes Evol. 216, 395–415. ( 10.1007/s00427-006-0085-4) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tanaka G, Hou X, Ma X, Edgecombe GD, Strausfeld NJ. 2013. Chelicerate neural ground pattern in a Cambrian great appendage arthropod. Nature 502, 364–367. ( 10.1038/nature12520) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Telford MJ, Thomas RH. 1998. Expression of homeobox genes shows chelicerate arthropods retain their deutocerebral segment. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 95, 10 671–10 675. ( 10.1073/pnas.95.18.10671) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hughes CL, Kaufman TC. 2002. Hox genes and the evolution of the arthropod body plan. Evol. Dev. 4, 459–499. ( 10.1046/j.1525-142X.2002.02034.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brenneis G, Ungerer P, Scholtz G. 2008. The chelifores of sea spiders (Arthropoda, Pycnogonida) are the appendages of the deutocerebral segment. Evol. Dev. 10, 717–724. ( 10.1111/j.1525-142X.2008.00285.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Struhl G. 1982. Genes controlling segmental specification in the Drosophila thorax. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 79, 7380–7384. ( 10.1073/pnas.79.23.7380) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Casares F, Mann RS. 1998. Control of antennal versus leg development in Drosophila. Nature 392, 723–726. ( 10.1038/33706) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Duncan DM, Burgess EA, Duncan I. 1998. Control of distal antennal identity and tarsal development in Drosophila by spineless–aristapedia, a homolog of the mammalian dioxin receptor. Genes Dev. 12, 1290–1303. ( 10.1101/gad.12.9.1290) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dong PDS, Chu J, Panganiban G. 2001. Proximodistal domain specification and interactions in developing Drosophila appendages. Development 128, 2365–2372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dong PDS, Dicks JS, Panganiban G. 2002. Distal-less and homothorax regulate multiple targets to pattern the Drosophila antenna. Development 129, 1967–1974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Emerald BS, Cohen SM. 2004. Spatial and temporal regulation of the homeotic selector gene Antennapedia is required for the establishment of leg identity in Drosophila. Dev. Biol. 267, 462–472. ( 10.1016/j.ydbio.2003.12.006) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Duncan D, Kiefel P, Duncan I. 2010. Control of the spineless antennal enhancer: direct repression of antennal target genes by Antennapedia. Dev. Biol. 347, 82–91. ( 10.1016/j.ydbio.2010.08.012) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Angelini DR, Kikuchi M, Jockusch EL. 2009. Genetic patterning in the adult capitate antenna of the beetle Tribolium castaneum. Dev. Biol. 327, 240–251. ( 10.1016/j.ydbio.2008.10.047) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shippy TD, Yeager SJ, Denell RE. 2009. The Tribolium spineless ortholog specifies both larval and adult antennal identity. Dev. Genes Evol. 219, 45–51. ( 10.1007/s00427-008-0261-9) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Toegel JP, Wimmer EA, Prpic N-M. 2009. Loss of spineless function transforms the Tribolium antenna into a thoracic leg with pretarsal, tibiotarsal and femoral identity. Dev. Genes Evol. 219, 53–58. ( 10.1007/s00427-008-0265-5) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rieckhof GE, Casares F, Ryoo HD, Abu-Shaar M, Mann RS. 1997. Nuclear translocation of extradenticle requires homothorax, which encodes an extradenticle-related homeodomain protein. Cell 91, 171–183. ( 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80400-6) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Smith FW, Angelini DR, Jockusch EL. 2014. A functional genetic analysis in flour beetles (Tenebrionidae) reveals an antennal identity specification mechanism active during metamorphosis in Holometabola. Mech. Dev. 132, 13–27. ( 10.1016/j.mod.2014.02.002) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Angelini DR, Kaufman TC. 2004. Functional analyses in the hemipteran Oncopeltus fasciatus reveal conserved and derived aspects of appendage patterning in insects. Dev. Biol. 271, 306–321. ( 10.1016/j.ydbio.2004.04.005) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mito T, Ronco M, Uda T, Nakamura T, Ohuchi H, Noji S. 2007. Divergent and conserved roles of extradenticle in body segmentation and appendage formation, respectively, in the cricket Gryllus bimaculatus. Dev. Biol. 313, 67–79. ( 10.1016/j.ydbio.2007.09.060) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ronco M, Uda T, Mito T, Minelli A, Noji S, Klingler M. 2008. Antenna and all gnathal appendages are similarly transformed by homothorax knock-down in the cricket Gryllus bimaculatus. Dev. Biol. 313, 80–92. ( 10.1016/j.ydbio.2007.09.059) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Damen WGM, Hausdorf M, Seyfarth E-A, Tautz D. 1998. A conserved mode of head segmentation in arthropods revealed by the expression pattern of Hox genes in a spider. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 95, 10 665–10 670. ( 10.1073/pnas.95.18.10665) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sharma PP, Schwager EE, Extavour CG, Giribet G. 2012. Hox gene expression in the harvestman Phalangium opilio reveals divergent patterning of the chelicerate opisthosoma. Evol. Dev. 14, 450–463. ( 10.1111/j.1525-142X.2012.00565.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sharma PP, Schwager EE, Extavour CG, Wheeler WC. 2014. Hox gene duplications correlate with posterior heteronomy in scorpions. Proc. R. Soc. B 281, 20140661 ( 10.1098/rspb.2014.0661) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Khadjeh S, Turetzek N, Pechmann M, Schwager EE, Wimmer EA, Damen WGM, Prpic N-M. 2012. Divergent role of the Hox gene Antennapedia in spiders is responsible for the convergent evolution of abdominal limb repression. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 109, 4921–4926. ( 10.1073/pnas.1116421109) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sharma PP, Schwager EE, Extavour CG, Giribet G. 2012. Evolution of the chelicera: a dachshund domain is retained in the deutocerebral appendage of Opiliones (Arthropoda, Chelicerata). Evol. Dev. 14, 522–533. ( 10.1111/ede.12005) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Prpic N-M, Damen WGM. 2004. Expression patterns of leg genes in the mouthparts of the spider Cupiennius salei (Chelicerata: Arachnida). Dev. Genes Evol. 214, 296–302. ( 10.1007/s00427-004-0393-5) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pechmann M, Prpic N-M. 2009. Appendage patterning in the South American bird spider Acanthoscurria geniculata (Araneae: Mygalomorphae). Dev. Genes Evol. 219, 189–198. ( 10.1007/s00427-009-0279-7) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sharma PP, Gupta T, Schwager EE, Wheeler WC, Extavour CG. 2014. Subdivision of arthropod cap-n-collar expression domains is restricted to Mandibulata. EvoDevo 5, 3 ( 10.1186/2041-9139-5-3) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sekiguchi K, Yamamichi Y, Costlow JD. 1982. Horseshoe crab developmental studies. I. Normal embryonic development of Limulus polyphemus compared with Tachypleus tridentatus. Prog. Clin. Biol. Res. 81, 53–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sharma PP, Kaluziak ST, Pérez-Porro AR, González VL, Hormiga G, Wheeler WC, Giribet G. 2014. Phylogenomic interrogation of Arachnida reveals systemic conflicts in phylogenetic signal. Mol. Biol. Evol. 31, 2963–2984. ( 10.1093/molbev/msu235) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Blackburn DC, Conley KW, Plachetzki DC, Kempler K, Battelle BA, Brown NL. 2008. Isolation and expression of Pax6 and atonal homologues in the American horseshoe crab, Limulus polyphemus. Dev. Dyn. 237, 2209–2219. ( 10.1002/dvdy.21634) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sharma PP, Schwager EE, Giribet G, Jockusch EL, Extavour CG. 2013. Distal-less and dachshund pattern both plesiomorphic and apomorphic structures in chelicerates: RNAinterference in the harvestman Phalangium opilio (Opiliones). Evol. Dev. 15, 228–242. ( 10.1111/ede.12029) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sutton MD, Briggs DEG, Siveter DJ, Siveter DJ, Orr PJ. 2002. The arthropod Offacolus kingi (Chelicerata) from the Silurian of Herefordshire, England: computer based morphological reconstructions and phylogenetic affinities. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B 269, 1195–1203. ( 10.1098/rspb.2002.1986) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Briggs DEG, Siveter DJ, Siveter DJ, Sutton MD, Garwood RJ, Legg D. 2012. Silurian horseshoe crab illuminates the evolution of arthropod limbs. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 109, 15 702–15 705. ( 10.1073/pnas.1205875109) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chen J, Waloszek D, Maas A. 2004. A new ‘great-appendage’ arthropod from the Lower Cambrian of China and homology of chelicerate chelicerae and raptorial antero-ventral appendages. Lethaia 37, 3–20. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Aria C, Caron J-B, Gaines R. 2015. A large new leanchoiliid from the Burgess Shale and the influence of inapplicable states on stem arthropod phylogeny. Palaeontology. ( 10.1111/pala.12161) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Janssen R, Eriksson BJ, Tait NN, Budd G. 2014. Onychophoran Hox genes and the evolution of arthropod Hox gene expression. Front. Zool. 11, 22 ( 10.1186/1742-9994-11-22) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Abu-Shaar M, Ryoo HD, Mann RS. 1999. Control of the nuclear localization of extradenticle by competing nuclear import and export signals. Genes Dev. 13, 935–945. ( 10.1101/gad.13.8.935) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ryoo HD, Mann RS. 1997. The control of trunk Hox specificity and activity by extradenticle. Genes Dev. 13, 1704–1716. ( 10.1101/gad.13.13.1704) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Saadaoui M, Merabet S, Litim-Mecheri I, Arbeille E, Sambrani N, Damen W, Brena C, Pradel J, Graba Y. 2011. Selection of distinct Hox–extradenticle interaction modes fine-tunes Hox protein activity. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 108, 2276–2281. ( 10.1073/pnas.1006964108) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yao L-C, Liaw GJ, Pai CY, Sun YH. 1999. A common mechanism for antenna-to-leg transformation in Drosophila: suppression of homothorax transcription by four HOM-C genes. Dev. Biol. 211, 268–276. ( 10.1006/dbio.1999.9309) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.