Abstract

We conducted a secondary analysis of a completed study of the differential efficacy and side effects of aripiprazole versus haloperidol in early-stage schizophrenia (ESS), a subpopulation of patients which does not include first episode or chronic patients. A subpopulation of 360 individuals with ESS were identified from a randomized, multi-center, double-blind study of 1294 individuals with schizophrenia at different stages of illness who were randomized to treatment with aripiprazole (ESS=237) or haloperidol (ESS=123) for one year. The primary outcome measure was response rate based on a 50% reduction of Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) total scores. Secondary outcomes included several efficacy and safety measures, as well as treatment discontinuation. More individuals in the aripiprazole group (48%) than in the haloperidol group (28%; p<0.01) completed the study. Response rates were greater in the aripiprazole group (38% [N=91]) than in the haloperidol group (22% [N=27]; p<0.01). Aripiprazole was associated with fewer extrapyramidal side effects. ESS subjects in the haloperidol group were more likely than those in the aripiprazole group to discontinue the study drug due to an adverse event other than worsening illness (29% and 11%, respectively; p<0.01), and efficacy differences were reduced by interventions to mitigate side effects (decreasing antipsychotic dose with or without adding antiparkinsonian medication). Aripiprazole has a favorable efficacy/safety profile in ESS and appeared to be superior to haloperidol on a number of efficacy and safety outcomes. However, excessive dosing of the antipsychotic medications, in particular haloperidol, may have played an important role in accounting for the differences between aripiprazole and haloperidol in this study.

Keywords: early-stage, aripiprazole, haloperidol, side effects, schizophrenia

1. Introduction

“Second-generation” antipsychotic medications (SGAs) have been considered promising for the treatment of first-episode (FE) schizophrenia because, as compared with “first-generation” antipsychotic medications (FGAs), they were thought to be more effective. To date, however, the evidence available on the effectiveness of SGA versus FGA treatment of early schizophrenia has been inconclusive. Some studies have found advantages for SGAs over FGAs on a variety of efficacy measures (Kahn et al., 2008; Lieberman et al., 2003a; Lieberman et al., 2005; Sanger et al., 1999; Schooler et al., 2005), while others have demonstrated comparability(Crespo-Facorro et al., 2006; Emsley, 1999; Gaebel et al., 2007; Green et al., 2006). The side effect profiles of these medications also require further elucidation; thus far, the high-potency FGA haloperidol has been associated with more EPS than have SGAs, and most SGAs appear to cause more weight gain and metabolic effects (Crespo-Facorro et al., 2006; Emsley, 1999; Gaebel et al., 2007; Green et al., 2006; Lieberman et al., 2003b; Sanger et al., 1999; Schooler et al., 2005; Zipursky et al., 2005).

Aripiprazole is a SGA which differs from earlier agents in that it acts as a partial agonist, rather than a full antagonist, at dopamine D2 receptors. It is also a partial agonist at dopamine D3 and serotonin 5-HT1A receptors and an antagonist at 5-HT2A receptors (Miyamoto et al., 2005). Aripiprazole has been shown to be superior to placebo (Cutler et al., 2006; Kane et al., 2002; McEvoy et al., 2007) and comparably effective to FGAs and other SGAs (Chan et al., 2007; Chrzanowski et al., 2006; Fleischhacker et al., 2009; Kane et al., 2002; Kane et al., 2007b; McQuade et al., 2004; Potkin et al., 2003) in reducing positive, and possibly negative, symptoms of schizophrenia and in decreasing the risk of relapse (Pigott et al., 2003). Aripiprazole may pose a lower risk of EPS than some FGAs (Kane et al., 2002; Kane et al., 2007b) and a lower risk of hyperprolactinemia than risperidone (Chan et al., 2007; Potkin et al., 2003). Moreover, aripiprazole causes fewer cardio-metabolic side effects, such as weight gain, dyslipidemia and diabetes mellitus, as compared with other SGAs (2004; Chrzanowski et al., 2006; McQuade et al., 2004; Newcomer et al., 2008; Newcomer and Haupt, 2006). The relatively favorable side effect profile of aripiprazole (Miyamoto S, 2008) may be particularly advantageous in the treatment of patients early in their psychotic illness, given this population’s heightened vulnerability to adverse medication effects (Chatterjee et al., 1995; McEvoy et al., 1991; Zipursky et al., 2005).

However, to date, no randomized, double-blind, clinical trials comparing aripiprazole with a FGA in the early stages of schizophrenia have been conducted. Therefore, to address the question of the comparative effectiveness of aripiprazole and haloperidol in adult early-stage schizophrenia (ESS) patients, we conducted a post hoc analysis of the data from a randomized, double-blind, multi-center study comparing these two drugs (Kane et al., 2007a; Kasper et al., 2003; Miller del et al., 2007). In that study, treatment with aripiprazole was found to be superior to treatment with haloperidol in terms of completion rate and several measures of response, including remission, in a large, heterogeneous sample of schizophrenia patients at various stages and different durations of their illness. The two treatments were similar on most measures of symptom change, though aripiprazole-treated patients showed more improvement on negative and depressive symptom scales. In addition, EPS including tardive dyskinesia occurred more often in individuals treated with haloperidol, and it was suggested that aripiprazole’s superiority was related to its greater tolerability. The objective of the present study was to investigate the potential differential effects of aripiprazole and haloperidol in the ESS patients who participated in this study. We hypothesized that aripiprazole would demonstrate superior efficacy and better tolerability than haloperidol in ESS. We found that aripiprazole has a favorable efficacy/safety profile in ESS and appeared to be superior to haloperidol on a number of efficacy and safety outcomes. However, excessive dosing of the antipsychotic medications, in particular haloperidol, may have played an important role in accounting for the differences between aripiprazole and haloperidol in this study.

2. Methods

The data for these post hoc analyses were pooled from a 52-week, double-blind, randomized controlled trial comparing aripiprazole with haloperidol in the treatment of schizophrenia, and consisted of domestic and international protocols with identical designs. The two protocols were prospectively designed for pooled analysis and the primary results have been previously reported (Kasper et al., 2003). The domestic protocol was conducted in 33 centers in the United States and the international protocol in 137 centers outside of the United States. Patients were enrolled between June, 1998 and October, 2000. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, Good Clinical Practice, and US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) regulations, and protocols were reviewed and approved by all local Institutional Review Boards. After complete description of the study to the subjects, written informed consent was obtained. The subjects’ caregivers or next of kin also provided written informed consent when required by the local Institutional Review Board. Additional details of the study design have been described previously (Kasper et al., 2003).

2.1. Study Population

Subjects were men and non-lactating women ages 18 to 65 years who met DSM-IV (American Psychiatric Assocation, 1994) criteria for schizophrenia and were experiencing an acute relapse. Other primary inclusion criteria were: (a) a total score ≥60 on the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) (Kay et al., 1987) with a score of at least 4 (i.e., moderate severity) on any two of the four items that constitute the PANSS psychotic items subscale at the time of the baseline visit; (b) a history of previous response to antipsychotic medication (excluding clozapine) and not considered refractory to FGAs; (c) a history of continuous outpatient treatment for at least one 3-month period during the previous year; and (d) medically stable as determined by physical examination, electrocardiogram (ECG), and routine laboratory testing (including pregnancy test, serum chemistries and urine toxicology). Exclusion criteria were: (a) currently in the FE of schizophrenia (i.e., first instance of symptoms of schizophrenia); (b) currently or recently (i.e., < 1 month) meeting DSM-IV (American Psychiatric Assocation, 1994) criteria for substance dependence; (c) previous participation in an aripiprazole study or receipt of an investigational medication within 4 weeks of the initial study visit; (d) presence of suicidal ideation or considered by an investigator to be at significant suicide risk; (e) considered likely to require prohibited concomitant medications during the time of study participation; and (f) presence of a psychiatric or neurological disorder (other than schizophrenia, medication-induced acute EPS or tardive dyskinesia [TD]) requiring current pharmacotherapy.

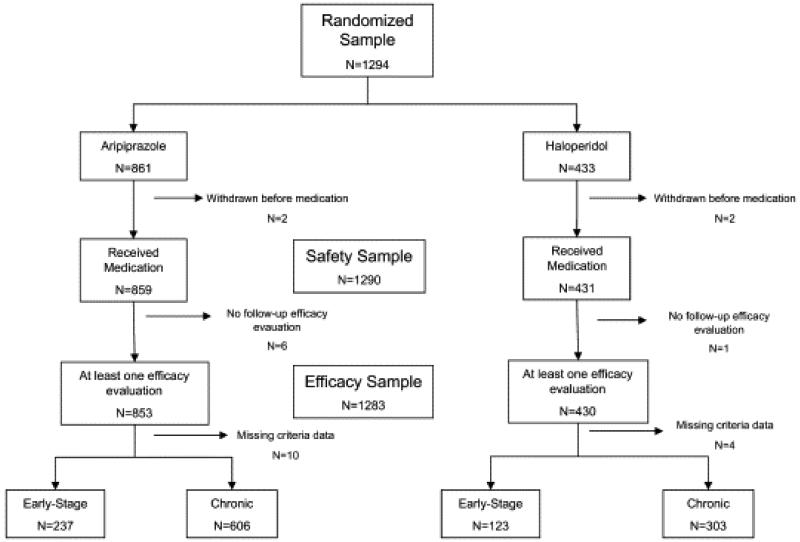

For the purposes of this post hoc analysis, ESS patients (n=360; Fig. 1) were defined by the following criteria, which were adapted from Sanger et al. (Sanger et al., 1999), in order to maintain consistency in the study of an early-stage subgroup of patients from a larger clinical trial: 1) duration of illness ≤5 years at time of enrollment, 2) age at onset of illness ≤40 years-old, and 3) not in the FE of psychosis (as defined above).

Fig. 1.

Consort Diagram

2.2. Intervention

After at least 5 days of placebo washout (or one depot cycle plus one week for subjects who had been taking depot antipsychotic medications), patients were randomized in a 2:1 ratio to two treatment arms: aripiprazole (30mg/day) or haloperidol (5mg/day for 3 days, then 10mg/day thereafter). Randomization numbers were assigned according to a permuted-block schedule, with blocking by study center. The washout period was shortened for those subjects whose mental state was judged to have deteriorated to the point of being harmful to their well-being. After one week, a one-time dose reduction was allowed based on tolerability to aripiprazole 20mg/day or haloperidol 7mg/day. Patients were followed for up to 52 weeks. No additional psychotropic medications were allowed, with the exception of oral benzodiazapines prescribed for anxiety or insomnia, and intramascular benzodiazapines prescribed for emerging agitation, up to a maximum of 4mg/day in lorazepam equivalents. Additionally, antiparkinsonian medications for the treatment of EPS were not allowed during the placebo washout phase but were allowed during the double-blind phase of the trial based on investigator judgment (≤6mg/day when benztropine was used).

2.3. Assessments

The primary outcome measure for this study was response rate, with response defined a priori as ≥50% improvement in PANSS total score, without a Clinical Global Impression-Improvement (CGI-I) (Guy, 1976b) score of 6 or 7; an adverse event of worsening schizophrenia; or a score of 5, 6 or 7 on any of the four PANSS psychotic items. In order to be considered a response, all of these criteria had to be met and maintained for at least 28 consecutive days. These criteria were chosen as they are the same criteria used in the parent study (Kasper et al., 2003), with the exception of the requirement for a ≥ 50% improvement in PANSS total score, which is more conservative than was used in the parent study (i.e., ≥ 20%). This more stringent response criterion was chosen a priori since this analysis involved a subpopulation from the parent study. Other efficacy measures included mean change from baseline to study endpoint in PANSS total score and in the PANSS positive, negative and general psychopathology symptom subscale scores; on the Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) (Montgomery and Asberg, 1979); and on the CGI-Severity (CGI-S) and CGI-I scales. Each scale was administered at weeks 1 through 8, 10, 12 and 14, and then every four weeks until week 52. Additional outcome measures were time to achieve response and time to discontinuation.

Adverse events and safety data were assessed at every visit utilizing self-report, direct clinical observation, vital sign and body weight measurements, ECGs, routine laboratory tests and physical examinations. Each patient was queried about untoward events and observed by the investigator for any signs indicative of adverse events at each study visit. EPS were also specifically and systematically assessed with the use of validated scales, including the Simpson-Angus Scale (Simpson and Angus, 1970), Abnormal Involuntary Movement Scale (Guy, 1976a) and the Barnes Akathisia Scale (Barnes, 1989). The scales, though used in this study, were not used to determine the presence or absence of adverse events, including tardive dyskinesia. Tolerability outcomes were the rates of adverse events and antiparkinsonian medication use.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were conducted on baseline characteristics in each treatment arm using t-tests for continuous variables and Chi-square or Fisher’s Exact tests for categorical variables and proportions. A Wilcoxon rank sum test was used to compare the duration on therapy between the two treatment arms and is reported as median duration in weeks (quartile 1, quartile 3). Efficacy was assessed on baseline to endpoint changes in PANSS total score, on PANSS subscales, on the MADRS and on CGI scales using observed cases and repeated-measures mixed model ANCOVAs, with baseline value as a covariate and protocol as a classification factor. In order to address confounding by differential tolerability, we also conducted exploratory mixed model analyses on patients maintained on target antipsychotic dose without antiparkinsonian medication, and patients requiring a dose reduction due to side effects with or without the addition of antiparkinsonian medication.

The proportion of responders in each treatment arm (observed cases) was analyzed using a cutoff point of a ≥50% change in the PANSS total score from baseline, as described above. In addition, time to achieve response using the same criteria and time to discontinuation of treatment were assessed using Cox proportional hazards analyses with baseline PANSS total score as a covariate and protocol as a stratification factor.

SAS (version 9.1.3, SAS Institute, Cary, NC) and a two-tailed P value of <0.05 were used for this study.

3. Results

3.1. Patients and Outcome

Of the 1294 patients who participated in the parent study, 360 were classified as ESS patients by our criteria, randomized to either aripiprazole (N=237) or haloperidol (N=123) and included in the final data analysis (Fig. 1). 35 (10%) of the ESS subjects participated in the domestic protocol and 325 (90%) in the international protocol. Aripiprazole- and haloperidol-treated ESS subjects were similar on all baseline demographic and clinical variables including treatment history except that ESS patients treated with aripiprazole had higher starting scores on the PANSS general psychopathology symptom subscale (Table 1). There were no baseline demographic, clinical, or treatment history differences within each of the two protocols (data not shown), except for a trend for ESS patients in the international protocol treated with aripiprazole to have higher starting scores on the PANSS general psychopathology symptom subscale (p=0.053). The mean daily dose of aripiprazole was 28.4 (SD=3.1) mg/day and that of haloperidol was 8.6 (SD=1.2) mg/day for ESS subjects.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of Early-Stage Subjects.

| Variable |

All (N = 360) |

Aripiprazole (N = 237) |

Haloperidol (N = 123) |

P-value a | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | ||

| Age (years) | 27.2 | 6.3 | 27.0 | 6.1 | 27.5 | 6.6 | 0.446 |

| Weight (kg) | 71.7 | 15.3 | 71.8 | 15.3 | 71.4 | 15.3 | 0.842 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 24.1 | 4.7 | 24.2 | 4.8 | 24.0 | 4.5 | 0.772 |

| PANSS total score | 94.3 | 15.4 | 95.2 | 15.1 | 92.5 | 15.8 | 0.117 |

| PANSS negative score | 24.4 | 6.0 | 24.7 | 5.8 | 23.8 | 6.2 | 0.209 |

| PANSS positive score | 24.2 | 4.7 | 24.1 | 4.5 | 24.3 | 5.2 | 0.695 |

| PANSS general score | 45.7 | 8.2 | 46.4 | 8.3 | 44.4 | 8.1 | 0.029 |

| CGI severity score | 4.8 | 0.8 | 4.8 | 0.7 | 4.8 | 0.8 | 0.774 |

| MADRS total score | 13.1 | 8.1 | 13.5 | 8.2 | 12.3 | 7.8 | 0.169 |

| Age at first episode | 24.4 | 6.0 | 24.2 | 5.9 | 24.8 | 6.2 | 0.378 |

| Number of hospitalizations | 2.4 | 2.5 | 2.3 | 2.2 | 2.5 | 3.1 | 0.486 |

| Weeks since relapse began | 3.9 | 4.6 | 4.0 | 5.1 | 3.7 | 3.5 | 0.497 |

| Length of treatment for current relapse (weeks) |

1.4 | 1.3 | 1.4 | 1.4 | 1.4 | 1.2 | 0.963 |

| Mean dose (mg/day) | 28.4 | 3.1 | 8.6 | 1.2 | |||

| N | % | N | % | N | % | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Men | 225 | 62.5 | 149 | 62.9 | 76 | 61.8 | 0.909 |

| Women | 135 | 37.5 | 88 | 37.1 | 47 | 38.2 | ||

| Race | White | 312 | 86.7 | 204 | 86.1 | 108 | 87.8 | 0.185 |

| Black | 33 | 9.2 | 25 | 10.5 | 8 | 6.5 | ||

| Hispanic | 3 | 0.8 | 3 | 1.3 | ||||

| Asian | 3 | 0.8 | 1 | 0.4 | 2 | 1.6 | ||

| Other | 9 | 2.5 | 4 | 1.7 | 5 | 4.1 |

t test for numeric variables and Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables.

Overall, 41% (N=148) of the ESS subjects completed the entire 52-week study. This included a significantly greater percentage in the aripiprazole group (48%, N=114) compared to the haloperidol group (28%, N=34) (p<0.01). The median period that patients continued on treatment and in the study was 40 weeks (8,52) for the aripiprazole group and 9 weeks (3,52) for the haloperidol group (p=0.0001). Using a Cox proportional hazards analysis, time to discontinuation was longer for the aripiprazole group than the haloperidol group (risk ratio=0.52; p<0.0001). ESS subjects in the haloperidol group were more likely than those in the aripiprazole group to discontinue the study drug due to an adverse event other than worsening illness (29% [N=36] and 11% [N=25], respectively; p<0.01). No other reason for discontinuation was significantly different between the two groups (i.e., lost to follow-up, withdrawal of consent, insufficient clinical response, adverse event of worsening schizophrenia, noncompliance, protocol violation, or patient met withdrawal criteria).

3.2. Efficacy

Aripiprazole was associated with a significantly greater response rate than haloperidol (38% [N=91] for aripiprazole and 22% [N=27] for haloperidol; p<0.01), while the time to achieve response did not differ between the groups (risk ratio=1.34; p=0.18).

Mean changes from baseline to endpoint on individual efficacy scales for the ESS group are shown in Table 2. Aripiprazole was superior to haloperidol with respect to changes in the PANSS total score and on the negative and general psychopathology symptom subscales, as well as on the MADRS, but not on the PANSS positive symptom subscale or the CGI-S scale.

Table 2.

Change from baseline to endpoint (52 weeks) on individual efficacy scales in early-stage subjects.

| Variable | Aripiprazole (N = 100) |

Haloperidol (N = 32) |

P-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| *LS Mean | SE | LS Mean | SE | ||

| PANSS total | −44.42 | 1.03 | −39.92 | 1.58 | 0.017 |

| PANSS negative | −10.01 | 0.3 | −8.68 | 0.46 | 0.016 |

| PANSS positive | −14.17 | 0.3 | −14.00 | 0.47 | 0.759 |

| PANSS general | −20.29 | 0.53 | −17.35 | 0.81 | 0.002 |

| CGI severity | −2.19 | 0.06 | −1.99 | 0.09 | 0.07 |

| MADRS total | −5.78 | 0.51 | −3.74 | 0.65 | 0.001 |

Mixed model, observed cases; LS, least square.

An additional analysis was performed to compare efficacy outcomes for ESS patients in the domestic and international ESS protocols. A significant difference in improvement in PANSS total scores was observed only for the international protocol (aripiprazole=−30.39, SE=1.74; haloperidol=−23.12, SE=2.41; p=0.02).

3.3. Safety

The haloperidol-treated subjects experienced significantly more EPS (i.e., dystonia, tremor, and extrapyramidal syndrome [i.e., parkinsonism or multiple EPS]; Table 3) than did aripiprazole-treated subjects. Similarly, a greater percentage of patients in the haloperidol group (18.7% [N=23]) than in the aripiprazole group (10.1% [N=24]) received antiparkinsonian medication (p=0.02). No other statistically significant differences were observed between treatment groups for any other side effect, including weight gain and gastrointestinal side effects (Table 3). One patient in the aripiprazole group, and none in the haloperidol group, developed tardive dyskinesia. Prolactin levels were not routinely measured.

Table 3.

Treatment-emergent adverse events among early-stage subjects for those events with an incidence >5%.

| Adverse event | Aripiprazole (N = 237) |

Haloperidol (N = 123) |

P-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | ||

| Asthenia | 12 | 5.1 | 6 | 4.9 | 0.939 |

| Headache | 18 | 7.6 | 12 | 9.8 | 0.482 |

| Dyspepsia | 12 | 5.1 | 4 | 3.3 | 0.429 |

| Nausea | 15 | 6.3 | 5 | 4.1 | 0.374 |

| Vomiting | 17 | 7.2 | 7 | 5.7 | 0.593 |

| Weight gain (i.e., ≥7%) | 18 | 7.6 | 5 | 4.1 | 0.194 |

| Agitation | 11 | 4.6 | 7 | 5.7 | 0.665 |

| Akathisia | 33 | 13.9 | 27 | 22.0 | 0.053 |

| Anxiety | 37 | 15.6 | 15 | 12.2 | 0.382 |

| Dystonia | 4 | 1.7 | 10 | 8.1 | 0.007 |

| Extrapyramidal syndrome | 28 | 11.8 | 49 | 39.8 | 0.000 |

| Insomnia | 42 | 17.7 | 23 | 18.7 | 0.819 |

| Nervousness | 10 | 4.2 | 8 | 6.5 | 0.346 |

| Psychosis | 28 | 11.8 | 18 | 14.6 | 0.447 |

| Salivation increased | 7 | 3.0 | 7 | 5.7 | 0.251 |

| Somnolence | 14 | 5.9 | 9 | 7.3 | 0.604 |

| Tremor | 6 | 2.5 | 9 | 7.3 | 0.031 |

Because of the disproportionate rates of EPS between treatments, and because EPS may affect clinical response (Geddes et al., 2000; Rosenheck, 2005), analyses were performed to examine the possible influence of adverse effects on therapeutic response. We compared the PANSS scores for ESS patients who stayed at the target antipsychotic dose without receiving antiparkinsonian medication and those for subjects who required an antipsychotic dose reduction with or without receiving additional antiparkinsonian medication due to an adverse event. Aripiprazole (N=71) remained superior to haloperidol (N=17) with respect to change in the PANSS total score among ESS subjects who remained at the target dose and did not receive antiparkinsonian medication (aripiprazole=−44.56, SE=1.21; haloperidol=−35.46, SE=2.19; p<0.01) and with respect to change on the negative (aripiprazole=−10.52, SE=0.34; haloperidol=−8.10, SE=0.64; p<0.01) and general psychopathology (aripiprazole=−20.39, SE=0.62; haloperidol=−15.17, SE=1.13; p<0.01) symptom subscales but not the PANSS positive symptom subscale (aripiprazole=−13.61, SE=0.35; haloperidol=−12.35, SE=0.64; p=0.09). In contrast, there were no significant differences in any PANSS total or subscale scores among those patients whose doses were reduced due to side effects, with or without the addition of antiparkinsonian medication.

4. Discussion

These findings would appear to be consistent with our primary hypothesis that aripiprazole would demonstrate superior efficacy and safety compared to haloperidol in the treatment of ESS, similar to the results from the parent study (Kasper et al., 2003), despite our more rigorously defined response criteria. The response rate, based on at least a 50% decrease in PANSS total scores (the primary outcome), was significantly greater in individuals treated with aripiprazole. In addition, aripiprazole treatment was associated with greater improvements on several PANSS scales and on the MADRS. Moreover, fewer subjects discontinued treatment with aripiprazole than with haloperidol. Treatment with aripiprazole was associated with fewer EPS. However, the results strongly suggest that excess dosing of aripiprazole and, in particular, haloperidol and/or inadequate management of EPS may have contributed to their differential side effect burdens and played a role in accounting for the differences in efficacy observed in this study.

In this context, our findings are consistent with prior studies showing that SGAs were more effective on several efficacy measures, including response rate, than the FGA haloperidol in the treatment of FE psychosis (Green et al., 2006; Kahn et al., 2008; Sanger et al., 1999; Schooler et al., 2005). In addition, these studies are consistent with our finding that, among ESS patients, treatment with a FGA resulted in more EPS than treatment with a SGA.

However, it has been extensively demonstrated that ESS patients are more sensitive to drug side effects and require lower doses of medications for therapeutic response (by 50% or more) than chronic patients (Chatterjee et al., 1995; Lieberman et al., 2003b; McEvoy et al., 1991). Previous studies have shown that haloperidol in FE psychosis causes more EPS than treatment with a SGA (Crespo-Facorro et al., 2006; Emsley, 1999; Gaebel et al., 2007; Green et al., 2006; Kahn et al., 2008; Lieberman et al., 2003b; Schooler et al., 2005). Consequently, it has been recommended that low doses of FGA medications be used in studies of FE patients (Gaebel et al., 2007; Kahn et al., 2008; Schooler et al., 2005).

Because the mean dose of haloperidol used in this study was 8.6mg/day, higher than doses used in the most recent FE trials (Gaebel et al., 2007; Kahn et al., 2008; Schooler et al., 2005), and in view of the pattern of results in this trial, we were prompted to consider whether the apparent superiority in efficacy of aripiprazole may have been due predominantly to the side effects of haloperidol. The higher dose of haloperidol could have been responsible for the high rates of EPS and increased and more rapid drop-out rate from the study. Moreover, discontinuation due to an adverse event other than worsening illness was the only significant difference in reason for treatment discontinuation between treatments. In addition, the efficacy differences on symptomatic response were seen in the measures that could be confounded with EPS including PANSS general psychopathology, negative symptoms, and MADRS, and not in PANSS positive symptoms (Miyamoto et al., 2005). Finally, when patients whose EPS were managed by dose reduction with or without the addition of antiparkinsonian medication were examined separately, all PANSS efficacy differences that were seen in the overall group of ESS patients disappeared.

Whether using a lower target dose of haloperidol from the outset of the study would have mitigated any efficacy differences is not clear. A meta-analysis by Geddes et al. (Geddes et al., 2000) showed that when dosages of comparator FGAs (primarily haloperidol) were kept lower, differences in efficacy or overall tolerability between FGAs and SGAs decreased or disappeared. Subsequent studies and meta-analyses that examined the comparative effectiveness of SGAs and FGAs, controlling for the potency and dose of FGAs, also support the potential interconnectedness of dosing, efficacy, and side effects of antipsychotic medications (Leucht et al., 2009; Leucht et al., 2003).

Alternatively, it is possible that aripiprazole was simply more efficacious than haloperidol in this study, an interpretation supported by the superior performance of aripiprazole in the subgroup of patients who did not have their haloperidol dose reduced or receive anticholinergic medication. This was the conclusion of another post hoc analysis of this dataset which reported that ESS patients treated with aripriprazole demonstrated greater utility (a composite measure of efficacy and tolerability) than those treated with haloperidol (Kane et al., 2009). However, this report did not adequately consider the possible differential effects of dosing and its consequent side effects. We believe that it is more likely that side effects, recognized and treated or not, played a role, due to the fact that the efficacy differences occurred in symptom domains that are more likely to be affected by EPS, and due to the relatively higher dosing of haloperidol used in this study.

A limitation of the present study is that it is a post hoc analysis of data obtained during the parent trial, which renders it susceptible to all of the methodological limitations of that trial, and to the risk of additional analyses yielding statistically significant results by chance alone. In addition, although the primary strengths of our post hoc analysis are that the parent trial was double-blinded and included a large sample size, the original trial was not originally designed or statistically powered to look at the ESS population.

The basis for the difference in results between the domestic and international protocols in the mean decreases in PANSS total scores is not entirely clear. Discrepant findings in two parallel clinical protocols have been reported and discussed previously (Rothschild et al., 2004).

In summary, our results suggest that aripiprazole has a promising efficacy-safety profile for the treatment of ESS, a subpopulation of patients that does not include chronic or FE patients. However, the conclusions must be considered in light of the potential for differential side effects caused by the dose of haloperidol or inadequate management of EPS.

Acknowledgments

None.

Role of Funding Source

This study was supported by Bristol-Myers Squibb and Otsuka America Pharmaceutical, Inc. The raw data and all data analyses were provided by Bristol-Myers Squibb and Otsuka America Pharmaceutical, Inc.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

Dr. Girgis has received research support from Janssen and Lilly through the American Psychiatric Institute for Research and Education and a travel stipend from Lilly, Forest, and Elsevier Science through the Society of Biological Psychiatry. Dr. Merrill and Dr. Vorel report no financial or other relationship relevant to the subject of this article. Dr. Kim, Dr. Portland, and Ms. You were employees of Bristol-Myers Squibb. Dr. Pikalov and Mr. Whitehead were employees of Otsuka America Pharmaceutical, Inc. Dr. Lieberman has received research grant support from Acadia, Allon, AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Forest Labs, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen, Merck, Organon, Pfizer, and Wyeth. He has acted as a consultant and an advisory board member for Astra-Zeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, GlaxoSmithKline, Eli Lilly, and Pfizer; has been a consultant for Cephalon, Johnson & Johnson and Novartis; an advisory board member for Bioline, Forest Labs, Lundbeck, Organon and Wyeth; and a DSMB member for Solvay. Dr. Lieberman has received no direct financial compensation or salary support for participation in research, consulting, advisory board or DSMB activities. Dr. Lieberman holds a patent for Repligen.

Contributors

The original study was designed and implemented by Bristol-Myers Squibb and Otsuka America Pharmaceutical, Inc. The analysis plan was developed by all authors. All data analyses were provided by Bristol-Myers Squibb and Otsuka America Pharmaceutical, Inc. All authors were involved in the data interpretation. Authors RRG, DBM, SRV, and JAL wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors contributed to and have approved the final version of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- Consensus development conference on antipsychotic drugs and obesity and diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2004;27:596–601. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.2.596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Assocation . Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. American Psychiatric Association; Washington, DC: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Barnes TR. A rating scale for drug-induced akathisia. Br J Psychiatry. 1989;154:672–6. doi: 10.1192/bjp.154.5.672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan HY, Lin WW, Lin SK, Hwang TJ, Su TP, Chiang SC, Hwu HG. Efficacy and safety of aripiprazole in the acute treatment of schizophrenia in Chinese patients with risperidone as an active control: a randomized trial. J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;68:29–36. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v68n0104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatterjee A, Chakos M, Koreen A, Geisler S, Sheitman B, Woerner M, Kane JM, Alvir J, Lieberman JA. Prevalence and clinical correlates of extrapyramidal signs and spontaneous dyskinesia in never-medicated schizophrenic patients. Am J Psychiatry. 1995;152:1724–9. doi: 10.1176/ajp.152.12.1724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chrzanowski WK, Marcus RN, Torbeyns A, Nyilas M, McQuade RD. Effectiveness of long-term aripiprazole therapy in patients with acutely relapsing or chronic, stable schizophrenia: a 52-week, open-label comparison with olanzapine. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2006;189:259–66. doi: 10.1007/s00213-006-0564-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crespo-Facorro B, Perez-Iglesias R, Ramirez-Bonilla M, Martinez-Garcia O, Llorca J, Luis Vazquez-Barquero J. A practical clinical trial comparing haloperidol, risperidone, and olanzapine for the acute treatment of first-episode nonaffective psychosis. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67:1511–21. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v67n1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cutler AJ, Marcus RN, Hardy SA, O’Donnell A, Carson WH, McQuade RD. The efficacy and safety of lower doses of aripiprazole for the treatment of patients with acute exacerbation of schizophrenia. CNS Spectr. 2006;11:691–702. doi: 10.1017/s1092852900014784. quiz 19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emsley RA, Risperidone Working Group Risperidone in the treatment of first-episode psychotic patients: a double-blind multicenter study. Schizophr Bull. 1999;25:721–9. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a033413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleischhacker WW, McQuade RD, Marcus RN, Archibald D, Swanink R, Carson WH. A double-blind, randomized comparative study of aripiprazole and olanzapine in patients with schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry. 2009;65:510–7. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.07.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaebel W, Riesbeck M, Wolwer W, Klimke A, Eickhoff M, von Wilmsdorff M, Jockers-Scherubl MC, Kuhn KU, Lemke M, Bechdolf A, Bender S, Degner D, Schlosser R, Schmidt LG, Schmitt A, Jager M, Buchkremer G, Falkai P, Klingberg S, Kopcke W, Maier W, Hafner H, Ohmann C, Salize HJ, Schneider F, Moller HJ. Maintenance treatment with risperidone or low-dose haloperidol in first-episode schizophrenia: 1-year results of a randomized controlled trial within the German Research Network on Schizophrenia. J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;68:1763–74. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v68n1116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geddes J, Freemantle N, Harrison P, Bebbington P. Atypical antipsychotics in the treatment of schizophrenia: systematic overview and meta-regression analysis. BMJ. 2000;321:1371–6. doi: 10.1136/bmj.321.7273.1371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green AI, Lieberman JA, Hamer RM, Glick ID, Gur RE, Kahn RS, McEvoy JP, Perkins DO, Rothschild AJ, Sharma T, Tohen MF, Woolson S, Zipursky RB. Olanzapine and haloperidol in first episode psychosis: two-year data. Schizophr Res. 2006;86:234–43. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2006.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guy W, Abnormal Involuntary Movement Scale (AIMS) Guy W, Guy Ws. ECDEU Assessment Manual for Psychopharmacology: Revised. Department of Health, Education, and Welfare; Washington, D.C.: 1976a. pp. 534–7. ADM 76-338. [Google Scholar]

- Guy W, Guy W, Guy Ws. ECDEU Assessment Manual for Psychopharmacology: Revised. Department of Health, Education, and Welfare; Washington, DC: 1976b. Clinical Global Impressions; pp. 217–22. ADM 76-338. [Google Scholar]

- Kahn RS, Fleischhacker WW, Boter H, Davidson M, Vergouwe Y, Keet IP, Gheorghe MD, Rybakowski JK, Galderisi S, Libiger J, Hummer M, Dollfus S, Lopez-Ibor JJ, Hranov LG, Gaebel W, Peuskens J, Lindefors N, Riecher-Rossler A, Grobbee DE. Effectiveness of antipsychotic drugs in first-episode schizophrenia and schizophreniform disorder: an open randomised clinical trial. Lancet. 2008;371:1085–97. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60486-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kane JM, Carson WH, Saha AR, McQuade RD, Ingenito GG, Zimbroff DL, Ali MW. Efficacy and safety of aripiprazole and haloperidol versus placebo in patients with schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2002;63:763–71. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v63n0903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kane JM, Crandall DT, Marcus RN, Eudicone J, Pikalov A, 3rd, Carson WH, Swyzen W. Symptomatic remission in schizophrenia patients treated with aripiprazole or haloperidol for up to 52 weeks. Schizophr Res. 2007a;95:143–50. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2007.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kane JM, Kim E, Kan HJ, Guo Z, Bates JA, Whitehead R, Pikalov A. Comparative utility of aripiprazole and haloperidol in schizophrenia: post hoc analysis of two 52-week, randomized, controlled trials. Appl Health Econ Health Policy. 2009;7:109–19. doi: 10.1007/BF03256145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kane JM, Meltzer HY, Carson WH, Jr., McQuade RD, Marcus RN, Sanchez R. Aripiprazole for treatment-resistant schizophrenia: results of a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, comparison study versus perphenazine. J Clin Psychiatry. 2007b;68:213–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasper S, Lerman MN, McQuade RD, Saha A, Carson WH, Ali M, Archibald D, Ingenito G, Marcus R, Pigott T. Efficacy and safety of aripiprazole vs. haloperidol for long-term maintenance treatment following acute relapse of schizophrenia. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2003;6:325–37. doi: 10.1017/S1461145703003651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kay SR, Fiszbein A, Opler LA. The positive and negative syndrome scale (PANSS) for schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 1987;13:261–76. doi: 10.1093/schbul/13.2.261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leucht S, Corves C, Arbter D, Engel RR, Li C, Davis JM. Second-generation versus first-generation antipsychotic drugs for schizophrenia: a meta-analysis. Lancet. 2009;373:31–41. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61764-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leucht S, Wahlbeck K, Hamann J, Kissling W. New generation antipsychotics versus low-potency conventional antipsychotics: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2003;361:1581–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13306-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lieberman JA, Phillips M, Gu H, Stroup S, Zhang P, Kong L, Ji Z, Koch G, Hamer RM. Atypical and conventional antipsychotic drugs in treatment-naive first-episode schizophrenia: a 52-week randomized trial of clozapine vs chlorpromazine. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2003a;28:995–1003. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lieberman JA, Tollefson G, Tohen M, Green AI, Gur RE, Kahn R, McEvoy J, Perkins D, Sharma T, Zipursky R, Wei H, Hamer RM. Comparative efficacy and safety of atypical and conventional antipsychotic drugs in first-episode psychosis: a randomized, double-blind trial of olanzapine versus haloperidol. Am J Psychiatry. 2003b;160:1396–404. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.8.1396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lieberman JA, Tollefson GD, Charles C, Zipursky R, Sharma T, Kahn RS, Keefe RS, Green AI, Gur RE, McEvoy J, Perkins D, Hamer RM, Gu H, Tohen M. Antipsychotic drug effects on brain morphology in first-episode psychosis. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62:361–70. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.4.361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEvoy JP, Daniel DG, Carson WH, Jr., McQuade RD, Marcus RN. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, study of the efficacy and safety of aripiprazole 10, 15 or 20 mg/day for the treatment of patients with acute exacerbations of schizophrenia. J Psychiatr Res. 2007;41:895–905. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2007.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEvoy JP, Hogarty GE, Steingard S. Optimal dose of neuroleptic in acute schizophrenia. A controlled study of the neuroleptic threshold and higher haloperidol dose. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1991;48:739–45. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1991.01810320063009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McQuade RD, Stock E, Marcus R, Jody D, Gharbia NA, Vanveggel S, Archibald D, Carson WH. A comparison of weight change during treatment with olanzapine or aripiprazole: results from a randomized, double-blind study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65(Suppl 18):47–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller del D, Eudicone JM, Pikalov A, Kim E. Comparative assessment of the incidence and severity of tardive dyskinesia in patients receiving aripiprazole or haloperidol for the treatment of schizophrenia: a post hoc analysis. J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;68:1901–6. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v68n1210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyamoto S, Duncan GE, Marx CE, Lieberman JA. Treatments for schizophrenia: a critical review of pharmacology and mechanisms of action of antipsychotic drugs. Mol Psychiatry. 2005;10:79–104. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyamoto S,MD, Lieberman JA, Fleischhacker WW, Marder SR, Tasman A, Maj M, First MB, Kay J, Lieberman JA, Tasman A, Maj M, First MB, Kay J, Lieberman J.A.s. Psychiatry. John Wiley & Sons; Hoboken, NJ: 2008. Antipsychotic Drugs; pp. 2161–201. [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery SA, Asberg M. A new depression scale designed to be sensitive to change. Br J Psychiatry. 1979;134:382–9. doi: 10.1192/bjp.134.4.382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newcomer JW, Campos JA, Marcus RN, Breder C, Berman RM, Kerselaers W, L’Italien G,J, Nys M, Carson WH, McQuade RD. A multicenter, randomized, double-blind study of the effects of aripiprazole in overweight subjects with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder switched from olanzapine. J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;69:1046–56. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v69n0702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newcomer JW, Haupt DW. The metabolic effects of antipsychotic medications. Can J Psychiatry. 2006;51:480–91. doi: 10.1177/070674370605100803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pigott TA, Carson WH, Saha AR, Torbeyns AF, Stock EG, Ingenito GG. Aripiprazole for the prevention of relapse in stabilized patients with chronic schizophrenia: a placebo-controlled 26-week study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2003;64:1048–56. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v64n0910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potkin SG, Saha AR, Kujawa MJ, Carson WH, Ali M, Stock E, Stringfellow J, Ingenito G, Marder SR. Aripiprazole, an antipsychotic with a novel mechanism of action, and risperidone vs placebo in patients with schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60:681–90. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.7.681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenheck RA. Open forum: effectiveness versus efficacy of second-generation antipsychotics: haloperidol without anticholinergics as a comparator. Psychiatr Serv. 2005;56:85–92. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.56.1.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothschild AJ, Williamson DJ, Tohen MF, Schatzberg A, Andersen SW, Van Campen LE, Sanger TM, Tollefson GD. A double-blind, randomized study of olanzapine and olanzapine/fluoxetine combination for major depression with psychotic features. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2004;24:365–73. doi: 10.1097/01.jcp.0000130557.08996.7a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanger TM, Lieberman JA, Tohen M, Grundy S, Beasley C, Jr., Tollefson GD. Olanzapine versus haloperidol treatment in first-episode psychosis. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156:79–87. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.1.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schooler N, Rabinowitz J, Davidson M, Emsley R, Harvey PD, Kopala L, McGorry PD, Van Hove I, Eerdekens M, Swyzen W, De Smedt G. Risperidone and haloperidol in first-episode psychosis: a long-term randomized trial. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162:947–53. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.5.947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson GM, Angus JW. A rating scale for extrapyramidal side effects. Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl. 1970;212:11–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1970.tb02066.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zipursky RB, Gu H, Green AI, Perkins DO, Tohen MF, McEvoy JP, Strakowski SM, Sharma T, Kahn RS, Gur RE, Tollefson GD, Lieberman JA. Course and predictors of weight gain in people with first-episode psychosis treated with olanzapine or haloperidol. Br J Psychiatry. 2005;187:537–43. doi: 10.1192/bjp.187.6.537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]