Abstract

Purpose

The HIV/AIDS epidemic in the United States is evolving due to factors including aging and geographical diffusion. Provider shortages are also driving the restructuring of HIV care delivery away from specialized settings, and family medicine providers may play a larger role in the future. We attempted to compare the effectiveness of HIV treatment delivered at community versus hospital care settings.

Methods

The outcome of interest was sustained virologic suppression defined as two consecutive HIV-1 RNA measurements ≤ 400 copies/mL within one year after antiretroviral initiation. We used data from the multi-state HIV Research Network cohort to compare sustained virologic suppression outcomes among 15,047 HIV-infected adults followed from 2000–2008 at five community- and eight academic hospital-based ambulatory care sites. Community-based sites were mostly staffed by family medicine and general internal medicine physicians with HIV expertise whereas hospital sites were primarily staffed by infectious disease subspecialists. Multivariate mixed-effects logistic regression controlling for potential confounding variables was applied to account for clustering effects of study sites.

Results

In an unadjusted analysis, the rate of sustained virologic suppression was significantly higher among subjects treated in the community-based care settings: 1,646/2,314 (71.1%) vs. 8,416/12,733 (66.1%) (p < 0.01). In the adjusted multivariate model with potential confounding variables, the rate was higher, although not statistically significant, in the community-based settings (AOR = 1.26, 95% CI 0.73–2.16).

Conclusion

Antiretroviral therapy can be delivered effectively through community-based treatment settings. This finding is potentially important for new program development to shift HIV care into community-based settings as the landscape of accountable care, health reform, and HIV funding and resources evolves.

Keywords: HIV primary care, community-based HIV care, virologic suppression

Introduction

The United States healthcare system is struggling with new human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infections and a diminishing HIV workforce1,2. These are occurring in the face of efforts to initiate early treatment for improved individual and public health outcomes3–5. Community-based and family medicine providers are increasingly called upon to deliver HIV care 6,7, and novel programs (e.g. the Health Resources and Services Administration’s (HRSA) “Expanding HIV Training into Graduate Medical Education” initiative) are attempting to expand education and address health disparities 8–11. HRSA reported that community health centers provided care to 94,605 HIV-positive patients in 2011, a 4.4% increase from 201012. Additionally, major efforts are underway to better engage and retain persons living with HIV (PLWH) into care: such efforts include timely diagnosis and utilization of community-based settings13–15.

Preliminary studies suggest community-based ambulatory care of PLWH may be comparable to hospital-based ambulatory care16,17. These are important findings given the changing epidemiology of HIV/AIDS, increasing longevity of PLWH, and multi-factorial chronic diseases which contribute to rapidly-evolving healthcare needs. HIV providers are also at risk for “provider burnout”18, and many longtime HIV providers are expected to retire soon, leaving a significant workforce shortage2,19. HIV treatment in the United States—often academic hospital-based and centralized around specialized resources—is likely to become integrated into community and primary care health centers, similar to what is done in areas with fewer resources20–23. This can help ensure that the broader needs of an enlarging population are adequately met.

The objectives of the present study were to: 1) describe HIV-infected adults followed at academic hospital-based versus community ambulatory care centers participating in a large consortium of HIV care sites, the HIV Research Network (HIVRN)24; and 2) compare effectiveness of one-year antiretroviral outcomes between the two care settings after controlling for potential confounding variables.

Methods

HIVRN study sites and research subjects

Currently the HIVRN consists of 18 sites (Appendix A) that provide ambulatory HIV services to adult sand children. All HIVRN sites are staffed by HIV experts and see a high volume of HIV-infected patients, ranging from ~350 to 5,000+ patients per site25. Each site’s participation in HIVRN is approved by their respective institutional review board. Data collected for HIVRN include demographic, clinical, treatment, laboratory, service utilization, and vital status information. Data elements are abstracted yearly from medical charts at each site via standardized protocols and submitted in a de-identified manner to HIVRN’s Data Coordinating Center. All participating sites are required to submit the same elements.

Community versus hospital setting

Community-based sites were community-oriented health centers or integrated healthcare systems whose primary purpose was to serve residents of the surrounding communities. Hospital sites were mainly academically-oriented “teaching” hospitals or hospital systems, although many provided care for residents of surrounding communities. Hospital sites were typically located within or adjacent to academic hospitals. All hospital-based sites are affiliated with an academic medical center whereas only one community-based site is academically affiliated. Study authors were blinded to specific location of care.

Antiretroviral therapy (ART)

For the large majority of this study’s review period, three main classes of ART were used: 1) nucleoside/nucleotide reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTI); 2) non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NNRTI); and 3) protease inhibitors (PI). Newer classes of agents, such as entry inhibitors and integrase inhibitors, were approved for use in the late 2000s—until recently, they were generally only used in patients who exhibited treatment failure on the more widely used, “first-line” agents. Combination ART was defined as a regimen with more than two drugs that included a PI, NNRTI, entry inhibitor, and/or other cornerstone drug; a regimen was identified as new if it was the start of therapy overall or if there was a change in the cornerstone drug.

Characteristics of providers

Both hospital and community based sites were staffed primarily by attending physicians that include infectious disease subspecialists, internal medicine providers with HIV expertise, and family medicine providers with HIV expertise. Specifically, community-based sites were staffed mostly by family medicine providers with HIV expertise and general internists with HIV expertise, although a few had infectious disease subspecialists on staff. In contrast, hospital-based sites were staffed primarily by infectious disease subspecialists. Mid-level providers such as physician assistants and nurse practitioners also provided direct patient care in the two settings, if not in every site. Attending physicians and mid-level providers had similar panel sizes (> 100 patients) and patient volume per half-day clinic session. The range of experience was comparable across the sites, from less than five to over 15 years. More details are provided elsewhere25.

Main outcome measure

The main outcome was sustained virologic suppression, defined as achievement of two consecutive plasma HIV-1 RNA viral load (VL) measurements ≤ 400 copies/mL within one year after starting any new combination ART regimen (see Appendix B for handling of incomplete VL measurements). Some subjects were on multiple regimens during the review period; however each subject was counted only once as either a treatment success, that is achievement of sustained virologic suppression as defined above, or a treatment failure. Subjects who achieved sustained virologic suppression on a particular regimen after previous failures were ultimately counted as a treatment success. Subjects on multiple regimens who never achieved sustained virologic suppression were counted as failures. In addition, because subjects had VL measured within the scope of routine care—rather than at pre-set times as with controlled trials—we examined values up to 14 months after ART initiation. There were no minimum or maximum criteria for time elapsed between the two consecutive VL ≤400 copies/mL, as long as both occurred within 14 months after an ART initiation.

Inclusion/exclusion criteria

For the present study, subjects were HIV-infected adults aged 18 years or older who initiated combination ART (cART) while enrolled in care any time between January 1, 2000 and December 31, 2008. Subjects were included if they had at least one outpatient medical visit and one CD4 measurement per year while enrolled in care, and if they started a new combination ART regimen for any duration during the review period. Subjects who started combination ART in 2008 were included if their laboratory data after December 31, 2008 were available for evaluation. Subjects were excluded if they had no CD4 or VL measurements available prior to the ART start date, or had no CD4 or VL measurements available after the regimen start date; these latter subjects were identified as “lost to follow-up”. Subjects were also excluded if pre-ART VL was ≤ 400 copies/mL. Finally, subjects were excluded if there were less than two VL measurements during the fourteen months after ART initiation. Subjects who died during the period of study were also excluded.

Included sites and subjects

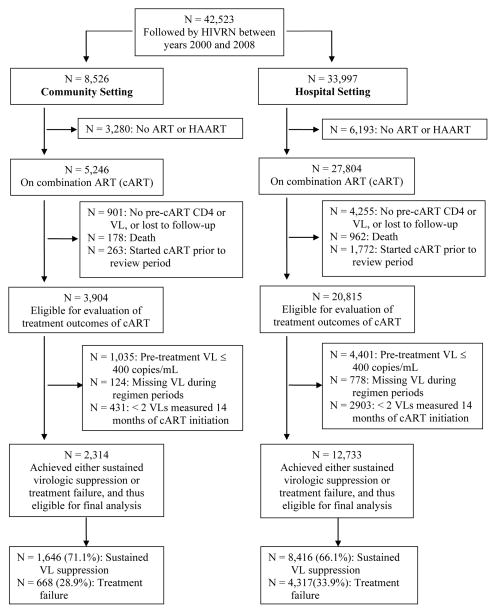

Fifteen adult sites we re initially included; these sites had complete data available through year 2008. Ten sites were hospital-based, and five were community-based ambulatory care sites. Across these fifteen sites, a total of 42,523 subjects were followed by HIVRN during the period of 2000–2008 years: from this overall cohort, 9,473 subjects were not on ART or combination ART, leaving 33,050 (77.8%) subjects on combination ART. From this population, five exclusionary conditions were accounted for: 1,140 died; 2,035 had actually started combination ART prior to the review period and were therefore ineligible for our outcome evaluation; 5,256 did not have at least oneCD4 and VL measurement available before and after ART start date; 5,436 subjects has pre-treatment VL ≤400 copies/mL; and 4,236 had missing or less than two VL measurements available during the review period after ART initiation. Figure 1 stratifies these numbers by settings of care.

Figure 1.

Flow chart showing selection of the included HIVRN for the analyses and their outcome

After application of the inclusion/exclusion criteria, all subjects from two of the original hospital sites were excluded, which resulted in a total of 15,047 subjects from the remaining thirteen sites for the present study analysis—eight hospital and five community sites. Specifically, the 15,047 subjects had definite ART treatment outcomes, either sustained VL suppression or treatment failure, and 12,733 (84.6%) were academic hospital-based and 2,314(15.4%) were community-based subjects.

Predictor variable

The predictor variable was the dummy-coded setting of HIV care: community-based or academic hospital-based setting of care.

Covariates of interest

Age at baseline, sex, self-reported race/ethnicity, HIV risk factor, pre-ART CD4, pre-ART VL, ART regimen type, and number of outpatient medical visits over the review period (per subject) were evaluated for the multivariate model. HIV risk factor was coded as heterosexual transmission; men who have sex with men (MSM); injection drug use (IDU), which included injection drug use in conjunction with other risk factors; or “other” that included unknown risk behavior. Except for subjects with IDU, these risk behaviors were treated as mutually exclusive. Initial CD4 was defined as the first CD4 measurement during the review period. Pre-ART CD4 and pre-ART VL were defined as the most recent CD4 and VL measurements preceding (or on) a regimen start date, respectively. CD4 increase was defined as the difference between pre-ART CD4 and the maximum CD4 attained after regimen initiation.

Statistical analysis

For descriptive statistics, we used percentages, means and standard deviations (SD) stratified by the two care settings. Categorical data on demographic and clinical characteristics were compared using Chi-square tests; continuous data were compared using student’s t-test or Wilcoxon rank-sum test as appropriate. A generalized linear mixed effects logistic model was applied to test the treatment outcomes between the two settings; the hospital setting was considered the referent setting. This model takes into account within-site binary outcome correlations for statistical inference by including sites as a random effect. We conducted bivariate analysis comparing success rates of sustained virologic suppression between the care settings using a Chi-square test. This analysis was followed by multivariate analysis to account for non-randomized patient allocation, variability in provider/practice type and differences in subject characteristics, including potential confounding variables that differed significantly between the two settings: age at baseline, sex, race/ethnicity, HIV risk factor, pre-ART CD4, pre-ART log10 VL, number of outpatient visits during review period, and regimen type. Differences were considered statistically significant at α = 0.05; reported confidence intervals are 2-sided. Statistical analysis was carried out using SAS 9.13 (Cary, North Carolina, USA). Specifically, we applied SAS GLIMMIX macro for the fit of the generalized linear mixed effects logistic model.

Results

Subject characteristics

Table 1 compares demographic, clinical, and healthcare utilization characteristics for subjects between care settings. There appeared to be no clinically meaningful differences in age between settings of care. Initial mean CD4 also did not differ significantly (272 cells/mm3 for community subjects vs. 277 cells/mm3 for hospital subjects). However, pre-ART mean CD4 was significantly higher (266 vs. 238 cells/mm3, p<0.01) and pre-ART mean log10 VL was significantly lower (4.3 vs. 4.5, p<0.01) for community subjects.

Table 1.

Subjects initiating combination antiretroviral therapy (ART) at community- and hospital-based ambulatory care settings within the HIV Research Network from 2000–2008

| Characteristic | Community-based care (n = 2,314) | Hospital-based care (n = 12,733) | p-valuea |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Age in years, mean (SD) | 38.5 (9.2) | 38.1 (9.1) | < 0.05 |

|

| |||

| Male, n (%) | 1,685 (72.8%) | 9,215 (72.4%) | NS |

|

| |||

| Race/ethnicity, n (%) | |||

| White | 828 (35.8%) | 3,459 (27.2%) | < 0.01 |

| African-American/Caribbean | 1,028 (44.4%) | 6,270 (49.2%) | |

| Hispanic | 386 (16.7%) | 2,727 (21.4%) | |

| Other | 72 (3.1%) | 277 (2.2%) | |

|

| |||

| HIV risk factor, n (%) | |||

| Heterosexual transmission | 995 (43.0%) | 4,487 (35.2%) | < 0.01 |

| MSM | 975 (42.1%) | 5,094 (40.0%) | |

| IDU | 288 (12.4%) | 2,589 (20.3%) | |

| Other | 37 (1.6%) | 197 (1.5%) | |

|

| |||

| Mean initial CD4 during review period in cells/mm3 (SD) | 272 (238) | 277 (240) | NS |

|

| |||

| Mean pre-ART CD4 in cells/mm3 (SD) | 266 (237) | 238 (201) | < 0.01 |

|

| |||

| Mean log10 pre-treatment viral load (SD) | 4.3 (0.9) | 4.5 (0.9) | < 0.01 |

|

| |||

| Mean number of outpatient visits per subject over review period (SD) | 35.4 (32.4) | 32.8 (26.6) | NS |

|

| |||

| Type of ART initiated, n (%) | |||

| PI only-based regimen | 1,200 (51.9%) | 6,758 (53.1%) | < 0.01 |

| NNRTI only-based regimen | 724 (31.3%) | 3,713 (29.2%) | |

| PI & NNRTI | 139 (6.0%) | 1,038 (8.2%) | |

| NRTI only | 146 (6.3%) | 844 (6.6%) | |

| Otherb | 105 (4.5%) | 380 (3.0%) | |

|

| |||

| Mean number of days on ART (index regimenc) (SD) | 632.7 (524.0) | 538.6 (473.2) | < 0.01 |

|

| |||

| Achievement of sustained virologic suppression, n (%) | 1,646 (71.1%) | 8,416 (66.1%) | < 0.01 |

|

| |||

| Mean CD4 increase in cells/mm3 (SD) | 215 (220) | 197 (208) | < 0.01 |

Notes:

p-values based on student’s t-test, Wilcoxon rank-sum test, or Pearson χ2.

Regimens which included at least one non-PI/NNRTI antiretroviral medication were labeled “Other”, regardless of whether a PI/NNRTI was concurrently prescribed as part of that regimen combination.

Index regimen refers to the regimen that contributed towards either sustained virologic suppression or treatment failure; for subjects with multiple occurrences of either outcome, the earliest qualifying regimen was counted as the index regimen; treatment start and stop dates were submitted by HIVRN study sites.

Abbreviations: SD = standard deviation, NS = not significant, MSM = men who have sex with men, IDU = intravenous drug use, PI = protease inhibitor, NNRTI = non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor, NRTI = nucleoside/nucleotide reverse transcriptase inhibitor

Treatment characteristics

Protease inhibitor-based regimens were started more frequently overall (53%) than NNRTI-based combinations (30%) in both academic hospital and community-based settings, and at relatively similar frequencies between the two care settings. Only 7% of ART-treated subjects in both settings started regimens containing both a PI and NNRTI, and even fewer (4%) started NRTI-only combinations or regimens containing “other” cornerstone agents (such as integrase and entry inhibitors). Mean length of time on ART for hospital-based subjects was significantly shorter compared to that of community-based subjects (539 vs. 633 days, p < 0.01). Mean CD4 increase was also significantly smaller for hospital-based subjects compared to that of community-based subjects (197 vs. 215 cells/mm3, p < 0.01).

Outcome comparisons between settings

Bivariate analysis revealed that subjects in community-based settings achieved a higher rate of sustained virologic suppression compared to those in the academic hospital-based settings (Table 1): 1,646/2,314 (71.1%) versus 8,416/12,733 (66.1%) (p < 0.01), a statistically significant difference. Furthermore, the multivariate analysis (Table 2) revealed that sustained virologic suppression among community-based subjects was more likely, if not statistically significantly, than among hospital-based patients (AOR = 1.26 [95%CI 0.73–2.17]).

Table 2.

Multivariable-adjusted estimates of sustained virologic suppression among adults initiating combination antiretroviral therapy (ART) in the HIV Research Network from 2000–2008

| Variables | Adjusted ORa for sustained virologic suppression [95% CI] | p-value |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Setting of care | ||

| Hospital-based ambulatory care | REF [--] | |

| Community-based ambulatory care | 1.26 [0.73–2.17] | NS |

|

| ||

| Age in years | ||

| ≥ 50 | REF [--] | |

| 40–49 | 0.82 [0.72–0.93] | < 0.01 |

| 30–39 | 0.70 [0.62–0.80] | < 0.01 |

| 18–29 | 0.65 [0.56–0.75] | < 0.01 |

|

| ||

| Sex | ||

| Male | REF [--] | |

| Female | 1.08 [0.98–1.19] | NS |

|

| ||

| Race/ethnicity | ||

| White | REF [--] | |

| African-American/Caribbean | 0.85 [0.77–0.94] | < 0.01 |

| Hispanic | 1.18 [1.05–1.33] | < 0.01 |

| Other | 1.31 [0.99–1.73] | NS |

|

| ||

| HIV risk factor | ||

| Heterosexual transmission | REF [--] | |

| MSM | 1.14 [1.03–1.27] | < 0.01 |

| IDU | 0.82 [0.74–0.91] | < 0.01 |

| Other | 0.91 [0.67–1.22] | NS |

|

| ||

| Pre-ART CD4 in cells/mm3 | ||

| < 50 | REF [--] | |

| 50–199 | 1.16 [1.05–1.29] | < 0.01 |

| 200–349 | 1.40 [1.26–1.57] | < 0.01 |

| 350–499 | 1.44 [1.25–1.65] | < 0.01 |

| ≥ 500 | 1.27 [1.09–1.47] | < 0.01 |

|

| ||

| Pre-ART log10 viral load | 0.76 [0.73–0.80] | < 0.01 |

|

| ||

| Number of outpatient visits during review period | ||

| ≥ 4 | REF [--] | |

| < 4 | 0.78 [0.57–1.08] | NS |

|

| ||

| Type of ART | ||

| PI only-based regimen | REF [--] | |

| NNRTI only-based regimen | 1.47 [1.35–1.60] | < 0.01 |

| NNRTI & PI | 0.73 [0.64–0.83] | < 0.01 |

| NRTI | 0.78 [0.68–0.90] | < 0.01 |

| Other | 2.79 [2.15–3.63] | < 0.01 |

Notes:

Multivariate odds ratios include adjustment for care setting, age, sex, race/ethnicity, HIV risk factor, pre-ART CD4, pre-ART log10 viral load, number of outpatient visits during review period, and ART regimen type.

Abbreviations: NS = not significant, MSM = men who have sex with men, IDU = intravenous drug use, PI = protease inhibitor, NNRTI = non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor, NRTI = nucleoside/nucleotide reverse transcriptase inhibitor

Finally, the odds ratio of sustained virologic suppression was higher with higher age and higher pre-ART CD4, but lower with higher pre-ART VL; lower pre-treatment VL is a known predictor of virologic suppression and time to suppression. There were also statistically significant variations in odds of sustained virologic suppression by race/ethnicity, HIV risk factor, and regimen type. Specifically, subjects who initiated NNRTI-based regimens and regimens based on “other” classes had significantly higher odds of achieving sustained virologic suppression compared to subjects who initiated PI-based regimens: adjusted odds ratios for these groups were 1.47 [95% CI 1.35–1.60] and 2.79 [95% CI 2.15–3.63], respectively.

Discussion

The present study is one of the largest we are aware of comparing virologic outcomes for HIV-infected patients starting combination ART in community versus academic hospital-based ambulatory care settings across the United States. Our results indicate that, among the HIV Research Network’s multi-site cohort, community-based subjects had favorable odds for sustained virologic suppression within one year compared to hospital-based subjects. These results build on other studies describing treatment outcomes in community-based and primary care settings16,17,26. Using data from urban cohorts, other researchers have demonstrated that patients followed by primary care/community-based clinicians achieved relatively high rates of virologic suppression (~60–70%), similar to specialty/hospital-based clinics.

Virologic suppression rates among our subjects (71% for community-based and 66% for hospital-based) are also comparable to those reported from Ryan White-funded grantees during the same time frame: 2007 HIVQUAL-US data indicate 57.6% of patients on ART maintained viral suppression, with an average clinic rate of 56.2% (the lowest and highest 10% performing clinics reported rates of ≤33.3% and ≥75.0%, respectively) 27. The slightly higher rates at HIVRN-affiliated centers (regardless of setting) may be attributed at least in part to high levels of provider expertise. These sites may also have access to resources such as adherence counselors, case managers, and/or pharmacy medication management programs28.

Some of our findings may have special implications for health service delivery. The overall values for initial and pre-ART CD4 for all subjects across both settings were alarmingly low, and well below recommended levels for ART initiation29. This underscores the importance of early HIV diagnosis and successful linkage-to-care programs so that timely treatment can be initiated. Community-and primary care-based settings which offer convenient, i.e. co-located, access to HIV treatment soon after diagnosis can potentially help increase the numbers of patients engaged in timely care. Furthermore, only one of the five HIVRN community-based sites is affiliated with an academic medical center whereas all of the hospital-based sites are; this suggests that an academic affiliation may not be necessary to deliver high-quality HIV care. Antiretroviral management is arguably the most sophisticated skill maintained by HIV providers and the least easily “systematized”; therefore it is paramount that appropriately trained providers are integrated into all HIV treatment settings to ensure delivery of high-quality care.

We noted that pre-ART CD4 was lower for hospital versus community-based subjects (238 vs. 266 cells/mm3) despite similar initial CD4 counts. This difference is likely explained by higher pre-treatment VL among hospital-based subjects and/or unmeasured variables such as active substance use or mental health disorders interfering with treatment initiation, rather than a difference in care quality30; nevertheless, the difference in pre-treatment log10VL (4.3 vs. 4.5) between the two settings may not be clinically meaningful even if statistically significant. In addition, many patients attending hospital-based settings may have been referred from inpatient units where they exhibited complications of advanced HIV disease, or from providers who had reached the limits of their expertise and were uncomfortable managing patients with complex resistance profiles. Though not statistically significant, the overall adjusted odds ratio of virologic suppression favoring community-based sites possibly reflects differences in patient disease severity (as evidenced by pre-treatment CD4 and VL values) rather than structural differences between the two settings; examination of the variance components revealed that between-clinic variation (14%) was smaller than within-clinic variation (86%), suggesting that the outcome variation was more attributable to individual subjects than care settings.

With regard to the types of ART initiated in the two settings, there did not appear to be major meaningful differences. Slightly more subjects initiated PI-based combinations in both groups—an unsurprising finding since more than 98% of subjects were antiretroviral-experienced (possibly because a sizeable portion had failed first-line, typically NNRTI-based regimens). Our finding that NNRTI only-based regimens had higher sustained suppression (AOR = 1.47) compared to PI only-based regimens maybe due to improved adherence with NNRTI-based regimens through decreased pill burden and/or fewer side effects. However, since we did not examine specific antiretroviral combinations, we cannot make any definitive conclusions about the comparative use of specific regimens in the two settings. Finally, the mean length of time on ART was significantly shorter for hospital-based subjects (632.7 vs. 538.6 days), which possibly reflects treatment discontinuation by hospital providers due to poor medication adherence and/or identification of treatment resistance. Further examination is necessary to clarify factors driving these findings, and potential future work involves detailed evaluation of the use of second/third-line, etc. combinations and antiretroviral resistance management by providers in different settings. It may also be worthwhile to examine other patient/disease-oriented outcomes for patients followed in these settings (for example, long-term virologic, immunologic, and/or clinical outcomes).

There are some limitations to this study. First, only five community-based sites contributed data—therefore our findings should be viewed as somewhat provisional, pending a larger sample of community-based HIV treatment centers. HIVRN’s community-based sites may not be completely representative of all community-based HIV care since they are located in urban areas, staffed by HIV experts, and see a high volume of HIV-infected patients. Our findings may not generalize to solo or small group practices, or treatment programs in rural locations where the model of HIV management may differ from that at the HIVRN sites. Another limitation is that the present study involved a secondary data analysis, and some potentially relevant variables (e.g., antiretroviral adherence) were not captured. Finally, a large portion of subjects were excluded (27,476/42,523 = 65%); however, analysis of the characteristics of the excluded subjects is beyond the scope of the present study and may deserve a separate independent study. As with any study, if there were unmeasured variables contributing to bias or limiting the generalizability of this work, our findings should be interpreted cautiously.

Strengths of this work include both the large size and nature of its subjects. The HIV Research Network involves a well-studied, multi-site cohort which uniquely represents a group of large-volume, community-based HIV practices, the likes of which will probably increase as HIV care becomes less centralized due to difficulties maintaining hospital/specialty-based practices—particularly in some areas because of financial and/or workforce limitations.

In conclusion, this work supports the potential value of community-based HIV care by demonstrating that one-year ART treatment outcomes do not significantly differ between subjects starting ART in community-based versus hospital-based settings. The epidemiology of HIV/AIDS in the U.S. is rapidly evolving due to several factors including patient aging, development of chronic co-morbidities, and geographical diffusion31. Provider shortages are also driving HIV service restructuring, and many believe HIV ought to be decentralized, or “mainstreamed” into community/primary care-oriented health centers; for example, only ~10% of community health centers receive funding through Part C of the Ryan White HIV/AIDS Program. Such restructuring is well aligned with National HIV/AIDS Strategy goals, namely reducing health disparities and addressing increasingly complex healthcare needs of an enlarging HIV-infected population. Our findings have potentially important implications for new policy initiatives to stimulate program development including the shift of HIV treatment into community-based settings.

Acknowledgments

Support: The HIV Research Network is supported by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (290-01-0012). This study was also supported in part by the Einstein-Montefiore Institute for Clinical and Translational Research (UL1 RR025750) and the Einstein-Montefiore Center for AIDS Research (P30AI051519).

The AHRQ is not responsible for the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript. The views expressed in this paper are those of the authors. No official endorsement by the AHRQ is intended or should be inferred.

Appendix A: HIVRN Participating Institutions (contributing HIVRN Principal Investigators by site)

Alameda County Medical Center, Oakland, California (Howard Edelstein, M.D.)

Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania (Richard Rutstein, M.D.)

Community Health Network, Rochester, New York (Roberto Corales, D.O.)

Community Medical Alliance, Boston, Massachusetts (James Hellinger, M.D.)

Drexel University, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania (Jeffrey Jacobson, M.D., Sara Allen, C.R.N.P.)

Henry Ford Hospital, Detroit, Michigan (Norman Markowitz, M.D.)

Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, Maryland (Kelly Gebo, M.D., Richard Moore, M.D., Allison Agwu M.D.)

Montefiore Medical Group, Bronx, New York (Robert Beil, M.D., Carolyn Chu, M.D.)

Montefiore Medical Center, Bronx, New York (Lawrence Hanau, M.D.)

Nemechek Health Renewal, Kansas City, Missouri (Patrick Nemechek, M.D.)

Oregon Health and Science University, Portland, Oregon (P. Todd Korthuis, M.D.)

Parkland Health and Hospital System, Dallas, Texas (Gary Sinclair, M.D., Laura Armas-Kolostroubis, M.D.)

St. Jude’s Children’s Hospital and University of Tennessee, Memphis, Tennessee (Aditya Gaur, M.D.)

St. Luke’s Roosevelt Hospital Center, New York, New York (Victoria Sharp, M.D.)

Tampa General Health Care, Tampa, Florida (Chararut Somboonwit, M.D.)

University of California, San Diego, La Jolla, California (Stephen Spector, M.D.)

University of California, San Diego, California (W. Christopher Mathews, M.D.)

Wayne State University, Detroit, Michigan (Jonathan Cohn, M.D.)

Appendix B: Handling of incomplete HIV-1 RNA viral load measurements

Due to HIVRN’s multi-site and longitudinal nature, multiple HIV-1 RNA assays were used across sites. Many VL measurements were recorded as “less than n” rather than a discrete value (the original database contained 23 unique n’s where n ranged from 0–5,000,000 copies/mL). We converted measurements recorded as “less than n” to the value of n itself if n was ≤ 400 copies/mL. Measurements recorded as “less than n” where n was > 400 copies/mL were treated as missing since such a record could not definitively be attributed to a particular reason such as data entry error. Similarly, measurements recorded as “greater than n” were converted to n if n was > 400 copies/mL, and treated as missing if n was ≤ 400 copies/mL. The number of measurements recoded as missing totaled only 192 out of 547,108 (< 0.1%) originally recorded measurements. Additionally, if a subject had more than one VL measurement recorded on the same date, the maximum value was used in order to maintain a conservative estimate for sustained virologic suppression. This occurred for 2,361 measurements, representing < 1% of the originally recorded values.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: None to declare

Author Contributions: CC, PM and MH conceived and designed the study; CC and MH drafted the manuscript; CC and CV acquired the data; CC, MH, AP, and GU conducted data management and statistical analysis; CC, MH and PAS interpreted the results; CC and MH jointly supervised all aspects of the present study; and all authors provided critical revision of the manuscript and approved the contents.

References

- 1.Stevens LC, Webb AA, Davis S, Corless I, Portillo C. HIV Care Provider Shortages Highlighted in National Meeting. Janac-Journal of the Association of Nurses in Aids Care. 2008 Nov-Dec;19(6):412–414. doi: 10.1016/j.jana.2008.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Adams J, Chacko K, Guiton G, Aagaard E. Training Internal Medicine Residents in Outpatient HIV Care: A Survey of Program Directors. J Gen Intern Med. 2010 Sep;25(9):977–981. doi: 10.1007/s11606-010-1398-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Valdiserri RO, Holtgrave DR, West GR. Promoting early HIV diagnosis and entry into care. AIDS. 1999 Dec 3;13(17):2317–2330. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199912030-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fleishman JA, Yehia BR, Moore RD, Gebo KA, Network HIVR. The Economic Burden of Late Entry Into Medical Care for Patients With HIV Infection. Med Care. 2010 Dec;48(12):1071–1079. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181f81c4a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Health HIV. [Accessed February 1, 2012];The state of HIV primary care: a shifting landscape. 2012 http://www.healthhiv.org/modules/info/files/files_4f280446b0c51.pdf.

- 6.Korthuis PT, Berkenblit GV, Sullivan LE, et al. General internists’ beliefs, behaviors, and perceived barriers to routine hiv screening in primary care. AIDS Educ Prev. 2011 Jun;23(3):70–83. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2011.23.3_supp.70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bradford JB, Coleman S, Cunningham W. HIV system navigation: An emerging model to improve HIV care access. Aids Patient Care STDS. 2007 Jun;21:S49–S58. doi: 10.1089/apc.2007.9987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fleishman JA, Yehia BR, Moore RD, Gebo KA, Agwu AL. Disparities in receipt of antiretroviral therapy among HIV-infected adults (2002–2008) Med Care. 2012 May;50(5):419–427. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31824e3356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Koester KA, Maiorana A, Vernon K, Myers J, Rose CD, Morin S. Implementation of HIV prevention interventions with people living with HIV/AIDS in clinical settings: Challenges and lessons learned. AIDS behav. 2007 Sep;11(5):S17–S29. doi: 10.1007/s10461-007-9233-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.The White House Office of National AIDS Policy. [Accessed December 17, 2013, 2013];National HIV/AIDS Strategy for the United States. 2010 Jul; http://www.whitehouse.gov/sites/default/files/uploads/NHAS.pdf.

- 11.Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) Newsroom. [Accessed December 18, 2012];HRSA awards $5.1 million to bolster HIV/AIDS training and technical assistance programs. 2011 http://www.hrsa.gov/about/news/pressreleases/110907hivtraining.html.

- 12.Valdiserri R. [Accessed December 16, 2013];Celebrating community helath centers. 2012 Aug 10; http://blog.aids.gov/2012/08/celebrating-community-health-centers.html.

- 13.Horstmann E, Brown J, Islam F, Buck J, Agins BD. Retaining HIV-Infected Patients in Care: Where Are We? Where Do We Go from Here? Clin Infect Dis. 2010 Mar;50(5):752–761. doi: 10.1086/649933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Thompson MA, Mugavero MJ, Amico KR, et al. Guidelines for Improving Entry Into and Retention in Care and Antiretroviral Adherence for Persons With HIV: Evidence-Based Recommendations From an International Association of Physicians in AIDS Care Panel. Ann Intern Med. 2012 Jun;156(11):817. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-156-11-201206050-00419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Health Resources and Services Administration and HIV AIDS Bureau. [Accessed December 12, 2013];Outreach: engaging people in HIV care; summary of a HRSA/HAB 2005 consultation on linking PLWH into care. 2006 http://hab.hrsa.gov/abouthab/files/hivoutreachaug06.pdf.

- 16.Rastegar DA, Fingerhood MI, Jasinski DR. Highly active antiretroviral therapy outcomes in a primary care clinic. Aids Care-Psychol Socio-Med Asp Aids/Hiv. 2003 Apr;15(2):231–237. doi: 10.1080/0954012031000068371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chu C, Umanski G, Blank A, Grossberg R, Selwyn PA. HIV-infected patients and treatment outcomes: an equivalence study of community-located, primary care-based HIV treatment vs. hospital-based specialty care in the Bronx, New York. Aids Care-Psychol Socio-Med Asp Aids/Hiv. 2010;22(12):1522–1529. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2010.484456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kerr ZY, Miller KR, Galos D, Love R, Poole C. Challenges, Coping Strategies, and Recommendations Related to the HIV Services Field in the HAART Era: A Systematic Literature Review of Qualitative Studies from the United States and Canada. Aids Patient Care STDS. 2013 Feb;27(2):85–95. doi: 10.1089/apc.2012.0356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.AAHIVM and HIVMA Medical Workforce Working Group. [Accessed December 12, 2013];Averting a crisis in HIV care: a joint statement of the American Academy of HIV Medicine (AAHIVM) and the HIV Medicine Association (HIVMA) on the HIV medical workforce. 2009 http://www.idsociety.org/uploadedFiles/IDSA/Policy_and_Advocacy/Current_Topics_and_Issues/Workforce_and_Training/Statements/AAHIVM%20HIVMA%20Workforce%20Statement%20062509.pdf.

- 20.Boulle A, Van Cutsem G, Hilderbrand K, et al. Seven-year experience of a primary care antiretroviral treatment programme in Khayelitsha, South Africa. AIDS. 2010 Feb;24(4):563–U561. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328333bfb7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cohen R, Lynch S, Bygrave H, et al. Antiretroviral treatment outcomes from a nurse-driven, community-supported HIV/AIDS treatment programme in rural Lesotho: observational cohort assessment at two years. J Int AIDS Soc. 2009;12:8. doi: 10.1186/1758-2652-12-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kredo T, Ford N, Adeniyi FB, Garner P. Decentralising HIV treatment in lower-and middle-income countries. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;(6):78. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009987.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rich ML, Miller AC, Niyigena P, et al. Excellent Clinical Outcomes and High Retention in Care Among Adults in a Community-Based HIV Treatment Program in Rural Rwanda. Jaids. 2012 Mar;59(3):E35–E42. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31824476c4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.The HIV Research Network. Hospital and outpatient health services utilization among HIV-infected patients in care in 1999. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2002 May 1;30(1):21–26. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200205010-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yehia BR, Gebo KA, Hicks PB, et al. Structures of Care in the Clinics of the HIV Research Network. Aids Patient Care STDS. 2008 Dec;22(12):1007–1013. doi: 10.1089/apc.2008.0093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fingerhood M, Rastegar DA, Jasinski D. Five-year outcomes of a cohort of HIV-infected injection drug users in a primary care practice. J Addict Dis. 2006;25(2):33–38. doi: 10.1300/J069v25n02_05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.New York State Department of Health AIDS Institute and the HIV/AIDS Bureau of the US Health Resources, Services Administration (HRSA) HIV/AIDS Bureau. HIVQUAL-US Annual Data Report: Based on 2007 Performance Data. 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 28.de Bruin M, Hospers HJ, van Breukelen GJP, Kok G, Koevoets WM, Prins JM. Electronic Monitoring-Based Counseling to Enhance Adherence Among HIV-Infected Patients: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Health Psychol. 2010 Jul;29(4):421–428. doi: 10.1037/a0020335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Panel on Antiretroviral Guidelines for Adults and Adolescents. [Accessed December 12, 2013];Guidelines for the use of antiretroviral agents in HIV-1-infected adults and adolescents. 2013 http://www.aidsinfo.nih.gov/contentfiles/lvguidelines/adultandadolescentgl.pdf.

- 30.Merlin JS, Westfall AO, Raper JL, et al. Pain, Mood, and Substance Abuse in HIV: Implications for Clinic Visit Utilization, Antiretroviral Therapy Adherence, and Virologic Failure. Jaids. 2012 Oct;61(2):164–170. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3182662215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chu C, Umanski G, Blank A, Meissner P, Grossberg R, Selwyn PA. Comorbidity-Related Treatment Outcomes among HIV-Infected Adults in the Bronx, NY. Journal of Urban Health-Bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine. 2011 Jun;88(3):507–516. doi: 10.1007/s11524-010-9540-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]