Abstract

The traditional structure to function paradigm conceives of a protein's function as emerging from its structure. In recent years, it has been established that unstructured, intrinsically disordered regions (IDRs) in proteins are equally crucial elements for protein function, regulation and homeostasis. In this review, we provide a brief overview of how IDRs can perform similar functions to structured proteins, focusing especially on the formation of protein complexes and assemblies and the mediation of regulated conformational changes. In addition to highlighting instances of such functional equivalence, we explain how differences in the biological and physicochemical properties of IDRs allow them to expand the functional and regulatory repertoire of proteins. We also discuss studies that provide insights into how mutations within functional regions of IDRs can lead to human diseases.

Keywords: disordered proteins, disorder-to-order transitions, macromolecular protein assemblies, IDRs in protein complexes

Introduction

The folding of polypeptides into structured proteins has traditionally been seen as a prerequisite for protein function. In recent years, segments called intrinsically disordered regions that do not fold autonomously into stable secondary and tertiary structures have also been shown to be functional in a diverse array of fundamental molecular processes.1–7 The propensity of a protein segment to be structured spans a continuous spectrum (Fig. 1): at the extreme ends, a protein with no intrinsically disordered regions is deemed a structured protein and conversely, a protein with a disordered sequence entirely devoid of structure is referred to as an intrinsically disordered protein (IDP). Over one third of proteins in higher eukaryotes have large disordered segments (>30 residues), referred to as intrinsically disordered regions (IDRs).8,9

Figure 1.

The level of disorder in proteins can vary greatly, even within what is traditionally considered a “structured domain” and a “disordered region.” Both structured domains and disordered regions are fundamental units of protein function, and most eukaryotic proteins are composed of both types of region. Reprinted with permission from Babu et al., Science, 2012, 337, 1460–1461, © American Association for the Advancement of Science.

The first molecular structure of a protein was determined for myoglobin10 and the ensuing expansion of protein structure investigations was driven by a focus on highly structured, relatively rigid proteins. Indeed, many important principles of protein sequence, structure, function, folding and stability have been derived from studies of these structured proteins.11–18 A number of recent studies have demonstrated that IDRs can perform functions and biological tasks that are comparable to structured proteins, and that in certain cases IDRs provide specialized functional advantages. Structured and disordered regions can also act synergistically, with IDRs enhancing a protein's versatility by increasing the number of possible functional states it can adopt.19 For instance, alternative splicing of disordered segments can modify protein function and rewire regulatory and signaling networks through the differential inclusion of IDRs that contain linear interaction motifs and/or post-translational modification sites.20–23 The differential inclusion of such disordered segments can mediate new protein interactions, and hence change the context in which the biochemical or molecular functions are carried out by the protein.21 We and others recently showed that the alternative splicing of disordered segments can rewire or fine-tune protein interactions in a tissue-specific manner, for example by including/excluding segments that directly interact with other proteins, DNA, RNA, or ligands20,21 (Fig. 2). Another mechanism by which functional versatility can be increased is by regulated unfolding or disorder-to-order transitions, which permits some proteins to functionally switch between the structured and disordered states. This provides another mechanism for synergy between disorder and order.24 In addition to enhancing a protein's versatility, IDRs can also directly regulate a protein's activity by influencing its half-life in cells.25,26 We and others have recently demonstrated that the length, composition, and position of disordered segments in proteins can affect the protein's half-life, and hence its function in cells.25,27,28 Yeast, mouse, and human proteins with terminal or internal IDRs have significantly shorter half-lives, likely because these features can promote the initiation of degradation by the proteasome (Fig. 3).

Figure 2.

The alternative inclusion or exclusion of tissue-specific exons can rewire interaction networks and modulate protein interactions. (A) When tissue-specific splicing gives rise to isoforms that differ in the presence of disordered protein segments, this can result in the rewiring of an interaction network in the respective tissues. This is illustrated with the PIP5K1C kinase gene that has an exon with different inclusion levels in cerebellum and lymph node. (B) Molecular mechanisms by which a tissue-specific segment can rewire or fine-tune protein interactions. Segments encoded by TS exons can include a region that directly interacts with other proteins, DNA, RNA, or ligands, or indirectly affect the protein's binding properties (e.g., affinity, kinetics, and selectivity). TS segments that are involved in interactions are less frequently domains and more often disordered regions that embed peptide-binding motifs. Reprinted with permission from Buljan et al., Mol Cell, 2012, 46, 871–883, © Cell Press.

Figure 3.

Long terminal or internal disordered segments can influence protein half-life by permitting efficient initiation of degradation by the proteasome. Within a protein, short disordered segments tend to correspond to long protein half-lives, while long disordered segments (i.e. at a terminal end or within the internal segment) are linked to shorter half-lives. Reprinted with permission from Van der Lee et al., Cell Rep, 2014, 8, 1832–1844, © Cell Press.

The importance of IDRs is further demonstrated by the finding that both the mis-regulation29 of IDRs and mutations within IDRs often detrimentally affect molecular function;30,31 indeed, 20% of all annotated missense disease mutations are within IDRs.32,33 In this review, we discuss recent research that highlights how disordered regions achieve functions that are comparable in scope and importance to structured domains, focusing on classical structural biology concepts such as protein complex and assembly formation, mediation of controlled conformational changes and allostery.

Formation of Protein Complexes and Assemblies

Protein interactions, ranging from stable obligate permanent complexes to transient interactions, are common in signaling and regulation pathways and serve critical roles in nearly all aspects of biology. Classical work in the field of protein complex formation has largely focused on the structural classification of protein-protein interactions34–36 (PPIs) and the assembly of protein complexes.37,38 These studies have provided important insights and have been successfully used to design new protein interfaces and assemblies, an important goal in nanomaterial engineering.39–41

Properties of protein complexes formed by IDRs

Disordered protein regions can also form functional complexes. Relative to interactions between structured protein regions, disordered regions tend to interact with lower affinity and therefore tend to be involved in more transient interactions (Fig. 4). Interactions between IDRs are frequently mediated by linear motifs42,43 (3–10 residues) and molecular recognition features44,45 (MoRFs, 10–70 residues), which both serve as sites of interaction.46 These features are positioned within disordered regions, but upon interaction with their partner, a defined conformation is often induced. These linear motifs and MoRFs tend to interact with low affinity, making their interactions more reversible and transient, and hence they tend to be common mediators of dynamic cell processes.47,48 However, high avidity interactions, which are relatively high affinity interactions that result from the accumulated strength of multiple low affinity interactions, can be achieved by combining linear motifs or MoRFs. An example is the endocytotic protein Eps15, which contains over a dozen linear motifs that help cluster AP2 complexes at endocytotic assembly zones.49,50 In some instances, IDRs can form more extensive (and consequently, high affinity) interfaces than ordered proteins, of a similar size, via the induced folding that can occur upon IDRs binding their target.2 It has been speculated that in these cases, fully structured proteins would need to be much larger to achieve similar interface sizes and high binding affinities, which would be unfavorable to the cell due to an increase in either cellular crowding or cell size.51,52

Figure 4.

The role of intrinsically disordered proteins (IDPs) and regions (IDRs) in mediating interactions and forming complexes. Compared with ordered proteins, disordered proteins perform these roles differently, for instance by binding more partners and having lower affinity interactions (Box 1). The E. coli protein RNase E, in which a disordered tail utilises molecular recognition feature (MoRF)-mediated binding to organize a functional degradasome complex, exemplifies the unique roles that IDRs can play in interactions and protein complex formation (Box 2). Mutations that disrupt the normal complex-forming behaviour of IDPs can lead to disease, for instance by altering linear motifs or conserved regulatory elements (Box 3).

IDRs can regulate complex formation in diverse ways. Although many IDRs fold upon complex formation,53 others maintain their disordered nature when in a complex.54 This facilitates complex formation by decreasing the associated entropic cost.54,55 IDRs contribute several other features that can further modulate entropic costs of interactions, which in turn can promote or inhibit the formation of interactions. For example, IDRs often possess numerous linear motifs which serve as binding sites, and this multivalency limits the conformational entropic cost of binding as only the motifs must become rigid upon binding and not the regions linking them (see Fig. 2 in Flock et al.56). Many important protein families contain large disordered elements in their functional regions that serve essential roles for complex formation and regulation. An example is the family of G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs), where specific disordered regions are critical for modulating and fine-tuning GPCR signaling due to their roles of facilitating interactions with signaling partners, undergoing specific disorder to order transitions, mediating protein complex assembly and tuning interaction specificity and affinity (see Fig. 2 in Venkatakrishnan et al.57).

Finally, because interactions of IDRs tend to be mediated by short stretches of residues, they are easily modifiable, for instance by post-translational modifications (PTMs).58 This allows the creation of simple biological switches,59 and several examples of this phenomenon are found in regulatory and signaling proteins60 such as in the cell cycle regulatory proteins p21 and p27, which are two well-characterized IDPs that function as cyclin-dependent kinase (Cdk) regulators.61 In this system, p21 and p27 promiscuously bind Cdk/cyclin complexes. The extended, Cdk-bound version of p27 presents various phosphorylation sites, which act to modulate its Cdk regulatory activity. Strikingly, through a specific phosphorylation, p27 can switch from inhibiting the Cdks to being a partial activator,61 demonstrating how IDPs can be dramatically repurposed by relatively minor changes via post-translational modifications.

Consequences of IDRs in protein complexes

Intrinsic disorder is often associated with binding promiscuity, or the ability to interact with diverse and often numerous binding partners.46,62,63 Interactions involving IDRs also often tend to be more transient.48 In accord with these two features, IDRs often serve as a platform or docking station for the assembly of multiprotein complexes, which help to mediate signal computation and propagation within the cell.64 These large, multisite docking proteins frequently function as central hub proteins within protein-protein interaction networks. Some of the most prominent PPI hubs, for example, p53 and BRCA1, are highly intrinsically disordered,65 and indeed it has been estimated that two thirds of all signaling proteins are highly disordered.66 As another example, the largely unstructured C-terminal half of the scaffolding protein RNase E organizes the Escherichia coli RNA degradasome complex.67 The long disordered region is punctuated by short 15 to 40 residue segments (MoRFs) that can fold upon recognition, and these regions have been identified as interaction sites for specific proteins and RNAs that are crucial to its degradasome function.68

While ordered proteins can achieve higher binding partner numbers by linking together multiple ordered domains,62 disordered proteins achieve this through a combination of short linear motifs and low complexity (highly repetitive) repeats. Due to their short length, many linear motifs may be linked together on a protein to form numerous binding sites,48 while the flexibility of low complexity regions may permit the binding of different targets.69 Binding promiscuity can also be achieved by the IDR adopting different conformations, as in the case of calmodulin. An IDR within the protein MBP binds to calmodulin, but due to the large number of conformations MBP-calmodulin can exist in, the same IDR can promiscuously bind other biomolecules such as membranes, cytoskeletal proteins and modifying enzymes.70

Because of the binding promiscuity of many IDRs, proteins with IDRs are tightly regulated and undergo strict control of their synthesis rates, abundances and lifetimes.25,29,71 This is because altered abundance of IDPs can lead to promiscuous interactions in cells due to an increased likelihood of off-target interactions, which may result in disease.29,72 The ability of IDPs to form numerous complexes also has significant consequences for proteome interconnectivity. ID segments tend to connect functional modules, thereby interweaving disparate parts of PPI networks.48,73 Within proteomes, the ID segments of proteins frequently contain the actual interacting regions,74 and interactions between wholly disordered proteins are enriched in the human PPI network.75

Importantly, due to the small number of residues that frequently make an interaction site in IDRs, functional sites can be more easily disrupted by mutations. For instance, the conserved proteosomal degradation motif in the highly disordered N-terminal region of the regulatory protein β-catenin (DEG_SCF_TRCP1_1, 32DpSGIHpS37, that mediates binding with WD40 repeat domain of the beta-TRCP subunit of the SCF-betaTRCP E3 ubiquitin ligase complex) is recurrently mutated in different types of cancers.31,33 Mutations in this motif alter the abundance of β-catenin, leading to gene expression changes that can result in cancers. It seems likely that mutations in linear motifs within IDRs have a greater impact on disease than is currently appreciated33 (Fig. 4).

In addition to mediating protein-protein interactions, disordered regions can also mediate interactions with nucleic acids.76–78 As a result, IDRs are enriched in DNA-binding and RNA binding proteins.79,80 Similar to linear motifs, conserved recognition elements (CoREs) in IDRs have been suggested to mediate DNA recognition, and mutations in these elements are often deleterious.81 For instance, the SOX2 P > R loss of function mutation in the KRPMNAFMVWS CoRE is associated with brain anomalies in humans.81,82

Formation of macromolecular protein assemblies

Macromolecular protein assemblies are large intracellular structures composed of numerous protein partners, often serving organisational roles. Due to their structural versatility and propensity to form multivalent and transient interactions, disordered proteins play a critical role in the formation and maintenance of macromolecular protein assemblies and spatially segregated structures by forming either amyloid-like polymers or proteinaceous droplets83 (Fig. 5). Low-complexity domains in disordered proteins can facilitate phase transitions, which are implicated in the formation of hydrogels as a result of their multivalency and ability to form low-affinity interactions. The ability of disordered proteins to undergo phase transition from a solution to a gel is likely to accompany the formation of large, dynamic supramacroscopic polymer gels from small protein assemblies.84 These hydrogel structures can influence the cell either through organisational roles, or by influencing subcellular activities directly. Whereas macromolecular structures composed of ordered proteins, such as certain cytoskeletal features and structures of muscle filaments, tend to be highly regular and relatively long-lived, disordered macromolecular complexes are especially suited for temporally variable structures undergoing substantial flux. IDPs that can form higher order assemblies and functional aggregates are tightly regulated so that their concentrations are low enough to prevent uncontrolled formation of such assemblies.71 Furthermore, transcripts that encode such assembly forming IDPs are tightly regulated and asymmetrically localised in cells in order to ensure that such assemblies are not formed at random places but in highly specific locations.85

Figure 5.

The role of IDRs in forming macromolecular assemblies. IDPs form assemblies that are different from ordered proteins. For instance, IDRs can undergo phase transitions to form hydrogels (Box 1). An example of this process is RNA granule formation, in which IDRs form hydrogels that allow the membraneless organisation of specific proteins and RNAs (Box 2). Mutations that disrupt the assembly formation of IDRs can cause diseases, for instance by causing aberrant aggregation of proteins, or by repurposing of low complexity domains into oncogenic transactivators (Box 3).

Hydrogels composed of disordered proteins have been implicated in numerous organisational roles. For example, RNA granules are membraneless structures containing specific mRNAs and RNA-binding proteins, and an amyloid-like hydrogel composed of disordered, repetitive regions is thought to be necessary to retain the requisite RNAs and RNA-binding proteins86,87 (Fig. 5). Hydrogels also play roles in the organization of P granules, or ribonucleoprotein organelles that determine Caenorhabditis elegans germ cells,88 as well as in neuronal myelin sheath formation.89 Importantly, post-translational modification of disordered proteins, such as (de-) phosphorylation of MEG proteins in C. elegans, regulates dynamics of RNA granules.90 Given these findings, it is probable that additional organisational roles of IDP-based hydrogels will continue to emerge. It has been speculated that in addition to serving local organisational roles (as mentioned in the preceding examples), molecules that undergo phase transition may serve more diffuse organisational roles throughout the cytoplasm.84,91

Hydrogels composed of disordered proteins have also been implicated in the selective transport between the cytoplasm and nucleus through the hydrogel-forming ability of disordered FG repeats in nucleoporins of nuclear pore complexes.92 Multivalent, interaction-mediated disordered assemblies can control the cell cycle93 and regulate fungal intercellular connectivity by aggregating at cell-cell channels.94 Additionally, higher-order disordered protein assemblies have been implicated in cell signaling processes,95 in the proper functioning of stereocilia tip links of inner ear hair cells involved in hearing,96 and in T-cell function and differentiation.97 Certain neurological disorders and cancers involve aberrant formation of these macromolecular assemblages (Fig. 5). For instance, mutations in RNA binding nuclear proteins FUS and TDP43 which form RNA granules and aid in splicing and mRNA stability, lead to cytoplasmic aggregation resulting in the neurodegenerative disease amyotrophic lateral sclerosis.98 On the other hand, the ability of the IDRs to form assemblages is exploited in cancers. For example, the low complexity domains of FUS, EWS, or TAF15 RNA binding proteins fuse with a variety of DNA binding domains, forming polymeric fibers which bind to the RNA polymerase II and function as transcriptional activation domains, driving cancer cell formation.99

In addition to organisational roles, macromolecular structure formation can directly influence cellular phenotypes. As an example, the linear motif-mediated formation of Nck–nephrin–N-WASP (neuronal Wiskott–Aldrich syndrome protein) protein droplets correlates with actin polymerising ability.84 Using dynamic light scattering and small angle X-ray scattering to monitor polymerisation and phase separation, it was found that the highly multivalent interactions between N-WASP and its partners Nck and nephrin induce a distinct liquid-liquid phase separation and create micron-level liquid droplets in solution. This is thermodynamically coupled to a sol-gel transition (macromolecular polymer gel formation) as increasing intermolecular bonding occurs. Within this system, the droplet formation is functionally important, as it is coupled to a stimulation of Arp2/3-mediated actin assembly.

Mediation of Controlled Conformational Transitions in Proteins

For many proteins, conformational changes are required for function. Despite these different conformations, structured proteins have few highly energetically favorable states. In contrast, in disordered proteins numerous conformations are equally energetically favorable100 (Fig. 6). Despite this inherent conformational flexibility, disordered regions are capable of undergoing the controlled, defined structural shifts associated with molecular function. Two dramatic (and opposite) types of conformational output for disordered proteins are disorder-to-order transitions and order-to-disorder transition (also known as regulated unfolding). In addition, increasing evidence suggests that disorder can play a central role in mediating allostery.

Figure 6.

The role of IDRs in mediating conformational transitions. Compared with structured proteins, disordered proteins exhibit higher conformational flexibility and can undergo different types of folding-related conformational shifts (Box 1). A unique type of conformational transition in IDRs, induced folding, is a critical mechanism for functional CREB-CBP interactions (Box 2). Mutations disrupting functional conformational shifts of IDRs can lead to diseases, for instance by disrupting the regions of structural disorder that normally undergo coupled binding and folding (Box 3).

Disorder-to-order transitions

Many disordered regions undergo transitions from a disordered to an ordered state upon binding an interaction partner such as another protein, DNA, or ligands. The two most prominent concepts that describe the kinetics of coupled binding and folding are conformational selection and induced folding.53,101–103 In conformational selection, disordered regions stochastically sample different conformations in their disordered state, and one conformation that is complementary to the binding partner is drawn from equilibrium (as in the binding of p53 to MDM2104). In the induced folding mechanism, nonspecific contacts are formed first, which induces the disordered segment to progressively fold into the correct structures as it forms more ligand-specific contacts. An example is the association of the KID domain to the KIX domain of CREB (Fig. 6): using NMR titrations and 15N relaxation dispersion, the dynamic folding upon binding that occurs when the phosphorylated kinase inducible activation domain (pKID) of the transcription factor CREB binds the KIX domain of CBP (CREB binding protein) was elucidated. These experiments have shown that upon binding to the KIX domain, pKID initially forms an ensemble of transient encounter complexes; while still bound, these intermediate states are progressively stabilized into their final state by intermolecular interactions found in the final bound state.105 This interaction has downstream effects on CREB target genes, including genes involved in gluconeogenesis.

Functional disorder-to-order changes also add an element of adaptability due to their ability to respond to environmental conditions.106 For example, in the mitochondrial inner membrane a redox-mediated disorder-to-order transition permits mammalian COX17 to transfer copper to cytochrome c oxidase.107,108 Nearly 20% of disease mutations cause aberrations in disorder-to-order transitions.30,109 For instance, the frameshift mutation in the GPCR Frizzled4 (Fz4) leads to a rare form of familial exudative vitreoretinopathy (Fig. 6). The mutation results in the loss of disorder, making the tail highly structured. This gain of structure induces the formation of aggregates in the endoplasmic reticulum, blocking the localization of the receptor to plasma membrane.110

Regulated unfolding and cryptic disorder

Another key type of controlled conformational transition that is gaining increasing recognition is the regulated unfolding of proteins.24,111 This concept states that (i) regulated unfolding can permit sampling of the conformational space and hence the functional space, and that (ii) a structured domain may have a function when it is partially or even fully unfolded. This is in contrast to the classical idea of a protein having one optimal, folded conformation that is critical for successful function. For example, the histone chaperone nucleophosmin exists in equilibrium between ordered and disordered forms, which have distinct functions and sub-cellular localizations. Nucleophosmin switches between these two states via the PTM-regulated unfolding of its N-terminal domain into a disordered state.112,113 Another example of PTM-mediated functional unfolding is KSRP, which is a protein that promotes AU-rich mediated mRNA decay. Phosphorylation within KSRP's N-terminal domain acts as a switch by unfolding its KH1 domain, leading to the protein's increased localization in the nucleus and hence impeding its ability to promote mRNA decay in the cytoplasm.114

Regulated protein unfolding has also been described as an output response in signal transduction pathways. For instance, phosphorylation leads to the partial unfolding of p27, causing selective p27 ubiquitination and degradation, which leads to a cascade that terminates in the cell's entry into the S phase of the cell cycle.111 On an even larger scale, cryptic disorder has been described to mediate organ-level effects. The elastic protein titin plays a large role in determining diastolic blood volume in the left ventricle of the heart; mechanical unfolding of titin immunoglobulin (Ig) domains exposes cryptic cysteines, which can then be S-glutathionylated. This S-glutathionylation decreases the stability and folding ability of the Ig domain, promoting the extended forms of titin and ultimately mediating the mechanochemical modulation of the elasticity of human cardiomyocytes.115

Like disorder-to-order transitions, regulated unfolding can also be responsive to environmental conditions. In a number of oxidation sensor proteins, large-scale structural rearrangements of domains into disordered states dramatically affect protein function. In bacterial Hsp33, an elevated oxidation status unfolds and activates the protein, allowing it to fulfil its chaperone role. The IDRs of Hsp33 permit it to preferentially stabilize structured folding intermediates under stress conditions and release them in more folding-competent states upon a return to low stress conditions.116

Mediation of allostery in protein structures

Allostery refers to the ability to influence events at a functional site by interactions at a distal site. A prominent example of allostery in structured proteins is hemoglobin, in which the binding of oxygen to one of the subunits induces conformational changes that are propagated to other subunits, raising their affinity for oxygen.117 Several IDRs have recently been shown to also enable allosteric coupling.118,119 Theoretical description of allostery indicates that IDRs allow for much higher modularity and tunability than ordered regions, suggesting they could play a crucial role in allosteric regulation120–124 (Fig. 7). Disordered regions can modulate how closely different domains are allosterically coupled, thereby optimizing allosteric responses120,125 and in general, proteins with higher intrinsic disorder are more amenable to allosteric modulation.126 This principle is illustrated by steroid hormone receptors (SHRs), which are allosterically regulated transcription factors.126 IDRs in certain regions of these receptors can optimize allosteric responses. Each major domain of SHR reversibly binds ligands, and IDRs modulate allosteric coupling, or the degree of perturbation propagation, between domains. The effect that IDRs have on coupling between domains depends on the conformational and interaction coupling energies between the domains. Before ligand binding, the SHR exists in an ensemble of conformations. Upon the binding of a ligand (e.g. cofactors binding to the disordered N-terminal/AF1 regions), ensemble probabilities are redistributed according to these coupling energies, but the exact redistribution also depends on the probabilities of each state before its binding. Upon considering these factors, a model emerges in which both the ensemble nature of the SHR and the conformational flexibility of certain IDRs seem to account for a long-standing problem in the field, which is how SHRs can have distinct tissue and cell specific effects.

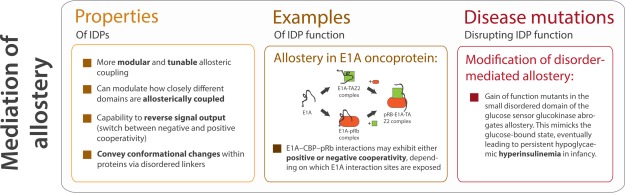

Figure 7.

The role of IDRs in mediating allostery. Disordered proteins can modulate allosteric mechanisms in proteins in a variety of ways (Box 1), and can reverse signal output by switching between positive and negative cooperativity, as in the case of E1A-CBP-pRB interactions (Box 2). Disruption of disorder-mediated allostery can manifest as disease states (Box 3).

At their extremes, IDPs may utilise allostery to reverse certain signals in addition to simply regulating signal strength as structured proteins do122 (Fig. 7). For example, using single-molecule Förster/fluorescence resonance energy transfer to study the binding processes of adenovirus early region 1A (E1A) oncoprotein, it was found that E1A–CBP–pRb interactions may exhibit either positive or negative cooperativity depending on which E1A interaction sites are exposed (through a biophysically complex mechanism, see Ferreon et al.127 for details). Briefly, the availability of the E1A N-terminal region can change the cooperativity of CBP TAZ2 and pRb binding to E1A. When only the C-terminal end of E1A is available for interaction, there is negative cooperativity between pRb and CBP TAZ2 (possibly due to the partial overlap between the pRb and CBP TAZ2 binding sites in the E1A CR1 region), meaning that the formation of the binary E1A complexes (E1A-pRb and E1A-CBP) is favored over the ternary complex (E1A-CBP-pRb).119 However, when the N-terminal end of E1A is available, there is positive cooperativity for the interactions between CBP TAZ2 and pRb, leading to more ternary complex formation. The positive cooperativity in ternary complex formation could enhance E1A's function to exit the cell cycle and promote cell differentiation, whereas the negative cooperativity could support the role of E1A as a promiscuous molecular hub IDP by increasing the population of binary complexes and thereby enhancing their activities.119 This allostery modulation controls the cell cycle and transcription119 and sheds light on the efficiency with which viral E1A disrupts host cell activities.128 Such cases of modulated allostery may be a common mechanism in IDP molecular hubs.2

Finally, disorder in loops and linker regions may help to facilitate signaling among a protein's domains, which is commonly viewed to occur via allosteric propagation, by helping to propagate strain energies.129 For instance, in sortase, a disorder-to-order transition of a loop co-operatively affects another loop region.130 The linkers in proteins can efficiently transfer information between sites on different domains, not solely because of their flexibility, but due to the encoding of successive conformational states within the linker sequence.131 For example, the glucocorticoid receptor (GR) fine tunes its target genes via allosteric effects propagated through its linker. Binding of the GR to DNA response elements induces conformational changes in the disordered lever arm, which in turn alters cofactor and coactivator binding sites in order to modulate glucocorticoid activity.131,132

Such active regulatory roles for linkers may potentially account for why mutations in linker regions that alter sequence or length sometimes disrupt protein function. For example, certain mutations of the regulatory linker in Tec kinases, which are tyrosine kinases implicated in hematopoietic cancers, can lead to constitutively active kinase domains.131 Mutations in the allosteric architecture of IDRs are known to cause a number of genetic disorders. This is seen in a small disordered region in glucokinase (GCK) that allows the concentration dependent allosteric modulation of the turnover rate, which is important for glucose homeostasis. Mutations in GCK can result in persistent hypoglycaemic hyperinsulinemia in infants (Fig. 7). Small molecule therapeutic agents that affect allosteric communication mediated by disordered regions are being investigated to treat these conditions.133

Conclusion

Recently, intrinsically disordered regions (IDRs) have emerged as fundamental units of protein function and regulation. Furthermore, IDRs have expanded our view of protein function by their involvement in areas once conceived of as the exclusive purview of structured domains. An explosive research effort into disordered proteins in the past decade has uncovered a plethora of functions for disordered regions; in this review, we have highlighted how IDRs can facilitate protein complex and assembly formation, orchestrate defined conformational transitions, and mediate allostery. We have also recently achieved a newfound understanding of the biomedical relevance of IDRs by discovering that IDR mutations can be of substantial consequence to disease causation by, for example, affecting functional features of IDRs (such as PTM sites or linear motifs), altering their disorder-to-order transitions, causing aggregation of IDRs or by changing protein half-lives. Since disordered regions can evolve rapidly, a major challenge is to make sense of disease mutation data within disordered regions from genome sequencing projects to uncover the relevant ones from the neutral mutations. The large number of significant biological discoveries that have emerged recently from the study of disordered proteins underscores their central importance in numerous aspects of cellular function. Given that the study of IDRs is in its infancy, it is indeed an exciting time for researchers to further investigate the properties, functionality and disease involvement of IDRs.

Acknowledgments

Since this is a review based on the Protein Science's Protein Society Young Investigator award lecture, the authors have in some instances emphasized the work done by their group, while highlighting work from other groups where appropriate. The authors apologize for not citing all relevant exciting studies from the literature, which are extensively captured in some of the reviews cited here. The authors thank I. Huppertz and A. S. Morgunov for their constructive feedback on the article.

References

- Van Der Lee R, Buljan M, Lang B, Weatheritt RJ, Daughdrill GW, Dunker AK, Fuxreiter M, Gough J, Gsponer J, Jones DT, Kim PM, Kriwacki RW, Oldfield CJ, Pappu RV, Tompa P, Uversky VN, Wright PE, Babu MM. Classification of intrinsically disordered regions and proteins. Chem. Rev. 2014;114:6589–6631. doi: 10.1021/cr400525m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright PE, Dyson HJ. Intrinsically disordered proteins in cellular signaling and regulation. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2015;16:18–29. doi: 10.1038/nrm3920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uversky VN. Intrinsically disordered proteins from A to Z. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2011;43:1090–1103. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2011.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tompa P. Intrinsically disordered proteins: a 10-year recap. Trends Biochem Sci. 2012;37:509–516. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2012.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oldfield CJ, Dunker AK. Intrinsically disordered proteins and intrinsically disordered protein regions. Annu Rev Biochem. 2014;83:553–584. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-072711-164947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gsponer J, Madan Babu M. The rules of disorder or why disorder rules. Prog Biophys Mol Biol. 2009;99:94–103. doi: 10.1016/j.pbiomolbio.2009.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uversky VN. A decade and a half of protein intrinsic disorder: biology still waits for physics. Protein Sci. 2013;22:693–724. doi: 10.1002/pro.2261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward JJ, Sodhi JS, McGuffin LJ, Buxton BF, Jones DT. Prediction and functional analysis of native disorder in proteins from the three kingdoms of life. J Mol Biol. 2004;337:635–645. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oates ME, Romero P, Ishida T, Ghalwash M, Mizianty MJ, Xue B, Dosztányi Z, Uversky VN, Obradovic Z, Kurgan L, Dunker AK, Gough J. D2P2: database of disordered protein predictions. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:D508–D516. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks1226. (Database issue): [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendrew JC, Bodo G, Dintzis HM, Parrish RG, Wyckoff HPD. A three-dimensional model of the myoglobin molecule obtained by X-ray analysis. Nature. 1958;181:662–666. doi: 10.1038/181662a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baase WA, Liu L, Tronrud DE, Matthews BW. Lessons from the lysozyme of phage T4. Protein Sci. 2010;19:631–641. doi: 10.1002/pro.344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chothia C. Principles that determine the structure of proteins. Annu Rev Biochem. 1984;53:537–572. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.53.070184.002541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fersht AR. From the first protein structures to our current knowledge of protein folding: delights and scepticisms. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2008;9:650–654. doi: 10.1038/nrm2446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chothia C, Finkelstein AV. The classification and origins of protein folding patterns. Annu Rev Biochem. 1990;59:1007–1039. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.59.070190.005043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X, Perica T, Teichmann SA. Evolution of protein structures and interactions from the perspective of residue contact networks. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2013;23:954–963. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2013.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laskowski RA, Thornton JM. Understanding the molecular machinery of genetics through 3D structures. Nat Rev Genet. 2008;9:141–151. doi: 10.1038/nrg2273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murzin AG, Brenner SE, Hubbard T, Chothia C. SCOP: a structural classification of proteins database for the investigation of sequences and structures. J Mol Biol. 1995;247:536–540. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1995.0159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chothia C, Gough J. Genomic and structural aspects of protein evolution. Biochem J. 2009;419:15–28. doi: 10.1042/BJ20090122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babu MM, Kriwacki RW, Pappu RV. Versatility from protein disorder. Science. 2012;337:1460–1461. doi: 10.1126/science.1228775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buljan M, Chalancon G, Eustermann S, Wagner GP, Fuxreiter M, Bateman A, Babu MM. Tissue-specific splicing of disordered segments that embed binding motifs rewires protein interaction networks. Mol Cell. 2012;46:871–883. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.05.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buljan M, Chalancon G, Dunker AK, Bateman A, Balaji S, Fuxreiter M, Babu MM. Alternative splicing of intrinsically disordered regions and rewiring of protein interactions. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2013;23:443–450. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2013.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis JD, Barrios-Rodiles M, Çolak R, Irimia M, Kim T, Calarco JA, Wang X, Pan Q, O'Hanlon D, Kim PM, Wrana JL, Blencowe BJ. Tissue-specific alternative splicing remodels protein-protein interaction networks. Mol Cell. 2012;46:884–892. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.05.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weatheritt RJ, Davey NE, Gibson TJ. Linear motifs confer functional diversity onto splice variants. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:7123–7131. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jakob U, Kriwacki R, Uversky VN. Conditionally and transiently disordered proteins: awakening cryptic disorder to regulate protein function. Chem Rev. 2014;114:6779–6805. doi: 10.1021/cr400459c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van der Lee R, Lang B, Kruse K, Gsponer J, Sánchez de Groot N, Huynen MA, Matouschek A, Fuxreiter M, Babu MM. Intrinsically disordered segments affect protein half-life in the cell and during evolution. Cell Rep. 2014;8:1832–1844. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.07.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inobe T, Matouschek A. Paradigms of protein degradation by the proteasome. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2014;24:156–164. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2014.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fishbain S, Inobe T, Israeli E, Chavali S, Yu H, Kago G, Babu MM, Matouschek A. Sequence composition of disordered regions fine-tunes protein half-life. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2015;22:214–221. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prakash S, Tian L, Ratliff KS, Lehotzky RE, Matouschek A. An unstructured initiation site is required for efficient proteasome-mediated degradation. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2004;11:830–837. doi: 10.1038/nsmb814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babu MM, van der Lee R, de Groot NS, Gsponer J. Intrinsically disordered proteins: regulation and disease. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2011;21:432–440. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2011.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vacic V, Iakoucheva LM. Disease mutations in disordered regions—exception to the rule? Mol Biosyst. 2012;8:27. doi: 10.1039/c1mb05251a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pajkos M, Mészáros B, Simon I, Dosztányi Z. Is there a biological cost of protein disorder? Analysis of cancer-associated mutations. Mol Biosyst. 2012;8:296. doi: 10.1039/c1mb05246b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vacic V, Markwick PRL, Oldfield CJ, Zhao X, Haynes C, Uversky VN, Iakoucheva LM. Disease-associated mutations disrupt functionally important regions of intrinsic protein disorder. PLoS Comput Biol. 2012;8:e1002709. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1002709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uyar B, Weatheritt RJ, Dinkel H, Davey E, Gibson TJ. Molecular biosystems proteome-wide analysis of human disease mutations in short linear motifs: neglected players in cancer? Mol Biosyst. 2014;10:2626. doi: 10.1039/c4mb00290c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones S, Thornton JM. Principles of protein-protein interactions. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:13–20. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.1.13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keskin O, Gursoy A, Ma B, Nussinov R. Principles of protein-protein interactions: what are the preferred ways for proteins to interact? Chem Rev. 2008;108:1225–1244. doi: 10.1021/cr040409x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janin J, Chothia C. The structure of protein-protein recognition sites. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:16027–16030. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsh JA, Hernández H, Hall Z, Ahnert SE, Perica T, Robinson CV, Teichmann SA. Protein complexes are under evolutionary selection to assemble via ordered pathways. Cell. 2013;153:461–470. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.02.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy ED, Pereira-Leal JB, Chothia C, Teichmann SA. 3D complex: a structural classification of protein complexes. PLoS Comput Biol. 2006;2:1395–1406. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.0020155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kortemme T, Joachimiak LA, Bullock AN, Schuler AD, Stoddard BL, Baker D. Computational redesign of protein-protein interaction specificity. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2004;11:371–379. doi: 10.1038/nsmb749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King NP, Bale JB, Sheffler W, McNamara DE, Gonen S, Gonen T, Yeates TO, Baker D. Accurate design of co-assembling multi-component protein nanomaterials. Nature. 2014;510:103–108. doi: 10.1038/nature13404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King NP, Sheffler W, Sawaya MR, Vollmar BS, Sumida JP, Andre I, Gonen T, Yeates TO, Baker D. Computational design of self-assembling protein nanomaterials with atomic level accuracy. Science. 2012;336:1171–1174. doi: 10.1126/science.1219364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davey NE, Van Roey K, Weatheritt RJ, Toedt G, Uyar B, Altenberg B, Budd A, Diella F, Dinkel H, Gibson TJ. Attributes of short linear motifs. Mol Biosyst. 2012;8:268. doi: 10.1039/c1mb05231d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Roey K, Uyar B, Weatheritt RJ, Dinkel H, Seiler M, Budd A, Gibson TJ, Davey NE. Short linear motifs: ubiquitous and functionally diverse protein interaction modules directing cell regulation. Chem Rev. 2014;114:6733–6778. doi: 10.1021/cr400585q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Disfani FM, Hsu WL, Mizianty MJ, Oldfield CJ, Xue B, Keith Dunker A, Uversky VN, Kurgan L. MoRFpred, a computational tool for sequence-based prediction and characterization of short disorder-to-order transitioning binding regions in proteins. Bioinformatics. 2012;28:i75–i83. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohan A, Oldfield CJ, Radivojac P, Vacic V, Cortese MS, Dunker AK, Uversky VN. Analysis of molecular recognition features (MoRFs) J Mol Biol. 2006;362:1043–1059. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.07.087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tompa P, Davey NE, Gibson TJ, Babu MM. A Million peptide motifs for the molecular biologist. Mol Cell. 2014;55:161–169. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2014.05.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh GP, Ganapathi M, Dash D. Role of intrinsic disorder in transient interactions of hub proteins. Proteins Struct Funct Genet. 2007;66:761–765. doi: 10.1002/prot.21281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cumberworth A, Lamour G, Babu MM, Gsponer J. Promiscuity as a functional trait: intrinsically disordered regions as central players of interactomes. Biochem J. 2013;454:361–369. doi: 10.1042/BJ20130545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Praefcke GJK, Ford MGJ, Schmid EM, Olesen LE, Gallop JL, Peak-Chew S-Y, Vallis Y, Babu MM, Mills IG, McMahon HT. Evolving nature of the AP2 alpha-appendage hub during clathrin-coated vesicle endocytosis. EMBO J. 2004;23:4371–4383. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmid EM, Ford MGJ, Burtey A, Praefcke GJK, Peak-Chew SY, Mills IG, Benmerah A, McMahon HT. Role of the AP2 beta-appendage hub in recruiting partners for clathrin-coated vesicle assembly. PLoS Biol. 2006;4:1532–1548. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0040262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunasekaran K, Tsai CJ, Kumar S, Zanuy D, Nussinov R. Extended disordered proteins: targeting function with less scaffold. Trends Biochem Sci. 2003;28:81–85. doi: 10.1016/S0968-0004(03)00003-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dyson HJ, Wright PE. Intrinsically unstructured proteins and their functions. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2005;6:197–208. doi: 10.1038/nrm1589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright PE, Dyson HJ. Linking folding and binding. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2009;19:31–38. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2008.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuxreiter M, Tompa P. Fuzzy complexes: a more stochastic view of protein function. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2012;725:1–14. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4614-0659-4_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tompa P, Fuxreiter M. Fuzzy complexes: polymorphism and structural disorder in protein-protein interactions. Trends Biochem Sci. 2008;33:2–8. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2007.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flock T, Weatheritt RJ, Latysheva NS, Babu MM. Controlling entropy to tune the functions of intrinsically disordered regions. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2014;26:62–72. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2014.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venkatakrishnan AJ, Flock T, Este D, Oates ME, Gough J, Babu MM. Structured and disordered facets of the GPCR fold. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2014;27:129–137. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2014.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roey V, Molecular E, Unit CB, Francisco S. Short linear motifs: ubiquitous and functionally diverse protein interaction modules directing cell regulation. Chem Rev. 2013;114:6733–6778. doi: 10.1021/cr400585q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Roey K, Gibson TJ, Davey NE. Motif switches: decision-making in cell regulation. Curr. Opin Struct Biol. 2012;22:378–385. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2012.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Roey K, Dinkel H, Weatheritt RJ, Gibson TJ, Davey NE. The switches.ELM resource: a compendium of conditional regulatory interaction interfaces. Sci Signal. 2013;6:rs7. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2003345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitrea DM, Yoon MK, Ou L, Kriwacki RW. Disorder-function relationships for the cell cycle regulatory proteins p21 and p27. Biol Chem. 2012;393:259–274. doi: 10.1515/hsz-2011-0254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patil A, Kinoshita K, Nakamura H. Domain distribution and intrinsic disorder in hubs in the human protein-protein interaction network. Protein Sci. 2010;19:1461–1468. doi: 10.1002/pro.425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schreiber G, Keating AE. Protein binding specificity versus promiscuity. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2011;21:50–61. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2010.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewitzky M, Simister PC, Feller SM. Beyond “furballs” and “dumpling soups” - towards a molecular architecture of signaling complexes and networks. FEBS Lett. 2012;586:2740–2750. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2012.04.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uversky VN, Oldfield CJ, Dunker AK. Intrinsically disordered proteins in human diseases: introducing the D2 concept. Annu Rev Biophys. 2008;37:215–246. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.37.032807.125924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iakoucheva LM, Brown CJ, Lawson JD, Obradović Z, Dunker AK. Intrinsic disorder in cell-signaling and cancer-associated proteins. J Mol Biol. 2002;323:573–584. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(02)00969-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcaida MJ, DePristo MA, Chandran V, Carpousis AJ, Luisi BF. The RNA degradosome: life in the fast lane of adaptive molecular evolution. Trends Biochem Sci. 2006;31:359–365. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2006.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Callaghan AJ, Aurikko JP, Ilag LL, Günter Grossmann J, Chandran V, Kühnel K, Poljak L, Carpousis AJ, Robinson CV, Symmons MF, Luisi BF. Studies of the RNA degradosome-organizing domain of the Escherichia coli ribonuclease RNase E. J Mol Biol. 2004;340:965–979. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.05.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coletta A, Pinney JW, Solís DYW, Marsh J, Pettifer SR, Attwood TK. Low-complexity regions within protein sequences have position-dependent roles. BMC Syst Biol. 2010;4:43. doi: 10.1186/1752-0509-4-43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagulapalli M, Parigi G, Yuan J, Gsponer J, Deraos G, Bamm VV, Harauz G, Matsoukas J, de Planque MR, Gerothanassis IP, Babu MM, Luchinat C, Tzakos AG. Recognition pliability is coupled to structural heterogeneity: A calmodulin intrinsically disordered binding region complex. Structure. 2012;20:522–533. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2012.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gsponer J, Babu MM. Cellular strategies for regulating functional and nonfunctional protein aggregation. Cell Rep. 2012;2:1425–1437. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2012.09.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vavouri T, Semple JI, Garcia-verdugo R, Lehner B. Intrinsic protein disorder and interaction promiscuity are widely associated with dosage sensitivity. Cell. 2009;138:198–208. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.04.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim I, Lee H, Han SK, Kim S. Linear motif-mediated interactions have contributed to the evolution of modularity in complex protein interaction networks. PLoS Comput Biol. 2014;10:e1003881. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1003881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunker AK, Cortese MS, Romero P, Iakoucheva LM, Uversky VN. Flexible nets: the roles of intrinsic disorder in protein interaction networks. FEBS J. 2005;272:5129–5148. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2005.04948.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimizu K, Toh H. Interaction between intrinsically disordered proteins frequently occurs in a human protein-protein interaction network. J Mol Biol. 2009;392:1253–1265. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2009.07.088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dyson HJ. Roles of intrinsic disorder in protein–nucleic acid interactions. Mol Biosyst. 2012;8:97. doi: 10.1039/c1mb05258f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuxreiter M, Simon I, Bondos S. Dynamic protein-DNA recognition: beyond what can be seen. Trends Biochem Sci. 2011;36:415–423. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2011.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vuzman D, Levy Y. Intrinsically disordered regions as affinity tuners in protein–DNA interactions. Mol Biosyst. 2012;8:47. doi: 10.1039/c1mb05273j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lobley A, Swindells MB, Orengo CA, Jones DT. Inferring function using patterns of native disorder in proteins. PLoS Comput Biol. 2007;3:1567–1579. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.0030162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castello A, Fischer B, Eichelbaum K, Horos R, Beckmann BM, Strein C, Davey NE, Humphreys DT, Preiss T, Steinmetz LM, Krijgsveld J, Hentze MW. Insights into RNA biology from an atlas of mammalian mRNA-binding proteins. Cell. 2012;149:1393–1406. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.04.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tayal N, Choudhary P, Pandit SB, Sandhu KS. Evolutionarily conserved and conformationally constrained short peptides might serve as DNA recognition elements in intrinsically disordered regions. Mol Biosyst. 2014;10:1469–1480. doi: 10.1039/c3mb70539k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider A, Bardakjian T, Reis LM, Tyler RC, Semina EV. Novel SOX2 mutations and genotype-phenotype correlation in anophthalmia and microphthalmia. Am J Med Genet A. 2009;149:2706–2715. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.33098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toretsky JA, Wright PE. 2014. ) Assemblages: functional units formed by cellular phase separation. 206:579–588.

- Li P, Banjade S, Cheng HC, Kim S, Chen B, Guo L, Llaguno M, Hollingsworth JV, King DS, Banani SF, Russo PS, Jiang QX, Nixon BT, Rosen MK. Phase transitions in the assembly of multivalent signaling proteins. Nature. 2012;483:336–340. doi: 10.1038/nature10879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weatheritt RJ, Gibson TJ, Babu MM. Asymmetric mRNA localization contributes to fidelity and sensitivity of spatially localized systems. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2014;21:833–839. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato M, Han TW, Xie S, Shi K, Du X, Wu LC, Mirzaei H, Goldsmith EJ, Longgood J, Pei J, Grishin NV, Frantz DE, Schneider JW, Chen S, Li L, Sawaya MR, Eisenberg D, Tycko R, McKnight SL. Cell-free formation of RNA granules: low complexity sequence domains form dynamic fibers within hydrogels. Cell. 2012;149:753–767. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.04.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han TW, Kato M, Xie S, Wu LC, Mirzaei H, Pei J, Chen M, Xie Y, Allen J, Xiao G, McKnight SL. Cell-free formation of RNA granules: bound RNAs identify features and components of cellular assemblies. Cell. 2012;149:768–779. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Goff L, Lecuit T. Developmental biology. Phase transition in a cell. Science. 2009;324:1654–1655. doi: 10.1126/science.1176523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aggarwal S, Snaidero N, Pähler G, Frey S, Sánchez P, Zweckstetter M, Janshoff A, Schneider A, Weil MT, Schaap IA, Görlich D, Simons M. Myelin membrane assembly is driven by a phase transition of myelin basic proteins into a cohesive protein meshwork. PLoS Biol. 2013;11:e1001577. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang JT, Smith J, Chen B, Schmidt H, Rasoloson D, Paix A, Lambrus BG, Calidas D, Betzig E, Seydoux G. Regulation of RNA granule dynamics by phosphorylation of serine-rich, intrinsically disordered proteins in C. elegans. Elife. 2014;3:e04591. doi: 10.7554/eLife.04591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brangwynne CP, Eckmann CR, Courson DS, Rybarska A, Hoege C, Gharakhani J, Jülicher F, Hyman AA. Germline P granules are liquid droplets that localize by controlled dissolution/condensation. Science. 2009;324:1729–1732. doi: 10.1126/science.1172046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labokha Aa, Gradmann S, Frey S, Hülsmann BB, Urlaub H, Baldus M, Görlich D. Systematic analysis of barrier-forming FG hydrogels from Xenopus nuclear pore complexes. EMBO J. 2013;32:204–218. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2012.302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee C, Zhang H, Baker A, Occhipinti P, Borsuk M, Gladfelter A. Protein aggregation behavior regulates cyclin transcript localization and cell-cycle control. Dev Cell. 2013;25:572–584. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2013.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai J, Koh CH, Tjota M, Pieuchot L, Raman V, Chandrababu KB, Yang D, Wong L, Jedd G. Intrinsically disordered proteins aggregate at fungal cell-to-cell channels and regulate intercellular connectivity. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2012;109:15781–15786. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1207467109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu H. Higher-order assemblies in a new paradigm of signal transduction. Cell. 2013;153:287–292. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.03.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu L, Pan L, Zhang C, Zhang M. Large protein assemblies formed by multivalent interactions between cadherin23 and harmonin suggest a stable anchorage structure at the tip link of stereocilia. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:33460–33471. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.378505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balagopalan L, Coussens NP, Sherman E, Samelson LE, Sommers CL. The LAT story: a tale of cooperativity, coordination, and choreography. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect Biol. 2010;2:a005512. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a005512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li YR, King OD, Shorter J, Gitler AD. Stress granules as crucibles of ALS pathogenesis. J Cell Biol. 2013;201:361–372. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201302044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwon I, Kato M, Xiang S, Wu L, Theodoropoulos P, Mirzaei H, Han T, Xie S, Corden JL, McKnight SL. Erratum: phosphorylation-regulated binding of RNA polymerase ii to fibrous polymers of low-complexity domains. Cell. 2014;156:374. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.10.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi UB, McCann JJ, Weninger KR, Bowen ME. Beyond the random coil: stochastic conformational switching in intrinsically disordered proteins. Structure. 2011;19:566–576. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2011.01.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunker AK, Oldfield CJ, Meng J, Romero P, Yang JY, Chen JW, Vacic V, Obradovic Z, Uversky VN. The unfoldomics decade: an update on intrinsically disordered proteins. BMC Genomics 9(Suppl. 2008;2):S1. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-9-S2-S1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen T, Song J, Chan HS. Science direct theoretical perspectives on nonnative interactions and intrinsic disorder in protein folding and binding. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2015;30:32–42. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2014.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiefhaber T, Bachmann A, Jensen KS. Dynamics and mechanisms of coupled protein folding and binding reactions. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2012;22:21–29. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2011.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiong K, Zwier MC, Myshakina NS, Burger VM, Asher SA, Chong LT. Direct observations of conformational distributions of intrinsically disordered p53 peptides using UV Raman and explicit solvent simulations. J Phys Chem A. 2011;115:9520–9527. doi: 10.1021/jp112235d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugase K, Dyson HJ, Wright PE. Mechanism of coupled folding and binding of an intrinsically disordered protein. Nature. 2007;447:1021–1025. doi: 10.1038/nature05858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Theillet F, Binolfi A. Physicochemical properties of cells and their effects on intrinsically disordered proteins (IDPs) Chem Rev. 2014;114:6661–714. doi: 10.1021/cr400695p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reichmann D, Jakob U. The roles of conditional disorder in redox proteins. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2013;23:436–442. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2013.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banci L, Bertini I, Cefaro C, Cenacchi L, Ciofi-Baffoni S, Felli IC, Gallo A, Gonnelli L, Luchinat E, Sideris D, Tokatlidis K. Molecular chaperone function of Mia40 triggers consecutive induced folding steps of the substrate in mitochondrial protein import. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:20190–20195. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1010095107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uversky VN, Davé V, Iakoucheva LM, Malaney P, Metallo SJ, Pathak RR, Joerger AC. Pathological unfoldomics of uncontrolled chaos: Intrinsically disordered proteins and human diseases. Chem Rev. 2014;114:6844–6879. doi: 10.1021/cr400713r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemma V, D'Agostino M, Caporaso MG, Mallardo M, Oliviero G, Stornaiuolo M, Bonatti S. A disorder-to-order structural transition in the COOH-tail of Fz4 determines misfolding of the L501fsX533-Fz4 mutant. Sci Rep. 2013;3:2659. doi: 10.1038/srep02659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitrea DM, Kriwacki RW. Regulated unfolding of proteins in signaling. FEBS Lett. 2013;587:1081–1088. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2013.02.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitrea DM, Grace CR, Buljan M, Yun MK, Pytel NJ, Satumba J, Nourse A, Park CG, Madan Babu M, White SW, Kriwacki RW. Structural polymorphism in the N-terminal oligomerization domain of NPM1. 2014;111:4466–4471. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1321007111. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitrea DM, Kriwacki RW. Cryptic disorder: an order-disorder transformation regulates the function of nucleophosmin. Pacific Symp Biocomput. 2012;2012:152–163. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Díaz-Moreno I, Hollingworth D, Frenkiel TA, Kelly G, Martin S, Howell S, García-Mayoral M, Gherzi R, Briata P, Ramos A. Phosphorylation-mediated unfolding of a KH domain regulates KSRP localization via 14-3-3 binding. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2009;16:238–246. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alegre-Cebollada J, Kosuri P, Giganti D, Eckels E, Rivas-Pardo JA, Hamdani N, Warren CM, Solaro RJ, Linke WA, Fernández JM. S-glutathionylation of cryptic cysteines enhances titin elasticity by blocking protein folding. Cell. 2014;156:1235–1246. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.01.056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reichmann D, Xu Y, Cremers CM, Ilbert M, Mittelman R, Fitzgerald MC, Jakob U. Order out of disorder: Working cycle of an intrinsically unfolded chaperone. Cell. 2012;148:947–957. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.01.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edelstein SJ. Cooperative interactions of hemoglobin. Annu Rev Biochem. 1975;44:209–232. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.44.070175.001233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Pino A, Balasubramanian S, Wyns L, Gazit E, De Greve H, Magnuson RD, Charlier D, van Nuland NAJ, Loris R. Allostery and intrinsic disorder mediate transcription regulation by conditional cooperativity. Cell. 2010;142:101–111. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.05.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferreon ACM, Ferreon JC, Wright PE, Deniz AA. Modulation of allostery by protein intrinsic disorder. Nature. 2013;498:390–394. doi: 10.1038/nature12294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilser VJ, Thompson EB. Intrinsic disorder as a mechanism to optimize allosteric coupling in proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:8311–8315. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0700329104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Motlagh HN, Li J, Thompson EB, Hilser VJ. Interplay between allostery and intrinsic disorder in an ensemble. Biochem Soc Trans. 2012;40:975–80. doi: 10.1042/BST20120163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilser VJ. Structural biology: Signaling from disordered proteins. Nature. 2013;498:308–310. doi: 10.1038/498308a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Motlagh HN, Wrabl JO, Li J, Hilser VJ. The ensemble nature of allostery. Nature. 2014;508:331–339. doi: 10.1038/nature13001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nussinov R, Tsai C-J. Allostery without a conformational change? Revisiting the paradigm. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2015;30:17–24. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2014.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilser VJ, Thompson EB. Structural dynamics, intrinsic disorder, and allostery in nuclear receptors as transcription factors. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:39675–39682. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R111.278929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenakin T, Miller LJ. Seven transmembrane receptors as shapeshifting proteins: the impact of allosteric modulation and functional selectivity on new drug discovery. Pharmacol Rev. 2010;62:265–304. doi: 10.1124/pr.108.000992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferreon ACM, Ferreon JC, Wright PE, Deniz AA. Modulation of allostery by protein intrinsic disorder. Nature. 2013;498:390–394. doi: 10.1038/nature12294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferreon JC, Martinez-Yamout MA, Dyson HJ, Wright PE. Structural basis for subversion of cellular control mechanisms by the adenoviral E1A oncoprotein. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:13260–13265. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0906770106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nussinov R. How do dynamic cellular signals travel long distances? Mol Biosyst. 2012;8:22. doi: 10.1039/c1mb05205e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moritsugu K, Terada T, Kidera A. Disorder-to-order transition of an intrinsically disordered region of sortase revealed by multiscale enhanced sampling. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:7094–7101. doi: 10.1021/ja3008402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma B, Tsai CJ, Haliloğlu T, Nussinov R. Dynamic allostery: linkers are not merely flexible. Structure. 2011;19:907–917. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2011.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Motlagh HN, Chakuroff C, Thompson EB, Hilser VJ. Thermodynamic dissection of the intrinsically disordered N-terminal domain of human glucocorticoid receptor. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:26777–26787. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.355651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larion M, Salinas RK, Bruschweiler-Li L, Miller BG, Brüschweiler R. Order-disorder transitions govern kinetic cooperativity and allostery of monomeric human glucokinase. PLoS Biol. 2012;10:e1001452. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]