Blood pressure (BP) reduction is a common pharmacodynamic feature of propofol, sevoflurane and other drugs used in general anaesthesia. The mechanisms by which propofol induces anaesthesia have been discussed 1,2. During total intravenous anaesthesia with propofol and sevoflurane anaesthesia, systolic and diastolic BP decreased by ∼30% 3–5. The underlying BP-lowering mechanisms of propofol and other anaesthetics are incompletely understood. Propofol is likely to induce hypotension by inhibiting the sympathetic nervous system and by impairing baroreflex regulatory mechanisms 5. Additional mechanisms may involve endogenous vasoactive species, including the vasoconstrictor thromboxane A2 (TxA2) and the vasodilatator nitric oxide (NO). During total intravenous anaesthesia with propofol in surgical patients, platelet-derived TxA2 was inhibited ex vivo, whereas the plasma concentrations of nitrite and nitrate, the major metabolites of NO 6, increased by 37% 7. As TxA2 is a potent vasoconstrictor and NO a potent vasodilatator, the BP-lowering actions of propofol could be related to TxA2 inhibition in platelets and concurrent enhancement of NO synthesis 7. In vitro, propofol inhibited TxA2 in human platelets while inducing inositol-1,4,5-trisphosphate formation, suggesting that propofol may both enhance and inhibit human platelet function, presumably depending upon its concentration 8. We observed that during general anaesthesia in patients undergoing elective spinal surgery, the plasma concentration of the endocannabinoid anandamide, an arachidonic acid derivative, rapidly decreased 9. Yet, in the same study we also observed a comparable decrease in plasma anandamide in thiopental–sevoflurane anaesthesia 9. Furthermore, anandamide is considered not to decrease BP on its own 10. Taking these findings together, BP lowering during anaesthesia may obey mechanisms that are not related to endogenous vasoactive substances, such as TxA2 and NO.

During total intravenous anaesthesia with propofol in surgical patients, plasma nitrite and nitrate concentrations ranged between 1 and 15 μmol l−1, with the majority of the concentrations being lower than 5 μmol l−1 7. This interval is much too low compared with the vast majority of reported data 6, and presumably resulted from the use of the Griess assay, with its analytical shortcomings 11.

We aimed to measure nitrite and nitrate concentrations in plasma samples obtained in a previously reported clinical study 9. We applied a fully validated and clinically proven gas chromatography–mass spectrometry method 12. This assay uses the stable-isotope-labelled analogues of nitrite and nitrate, i.e. 15N-nitrite and 15N-nitrate, as internal standards.

As reported earlier 9, all patients received standard doses of midazolam, atracurium and fentanyl/remifentanil. Induction of anaesthesia was achieved with either propofol or with thiopental plus sevoflurane. Blood samples were collected in EDTA-containing tubes before injection of propofol or thiopental (0 min) and 10, 30 and 60 min after induction. Vacutainers were immediately cooled and centrifuged at 4°C (10 min, 3500g). Plasma was then quickly separated from blood cells and kept on ice until storage at −80°C. In the present study, nitrite and nitrate were measured in nonhaemolytic plasma samples of 32 patients who had undergone propofol (n = 18) or thiopental–sevoflurane anaesthesia (n = 14). In brief, nitrite and nitrate were determined simultaneously in 100 μl aliquots of thawed plasma samples using 15N-nitrite and 15N-nitrate at added final plasma concentrations of 4 and 40 μmol l−1, respectively. Study samples were analysed by the same experimenter within five runs alongside quality control samples as reported elsewhere 12. Accuracy and imprecision (relative standard deviation) were (mean ± SD) 108.3 ± 5.4% and 1.75 ± 1.85% for plasma nitrite, and 105.9 ± 3.4% and 3.64 ± 4.03% for plasma nitrate, respectively, indicating the reliability of the nitrite and nitrate plasma concentrations measured in the study samples.

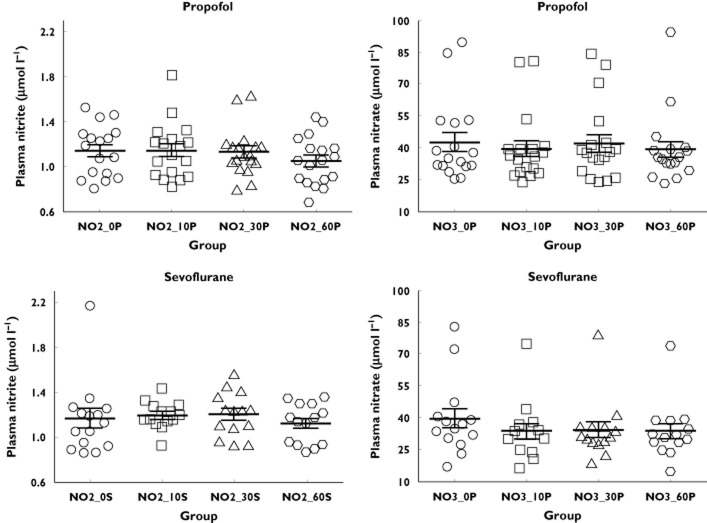

The results of the present study are depicted in Figure 1. Plasma nitrite and nitrate concentrations measured in the study were of the same order of magnitude reported by us and others (for a review see Tsikas et al. 6). Plasma nitrite and nitrate concentrations measured 10, 30 and 60 min after the start of anaesthesia did not differ from those measured at time zero, i.e. immediately before starting anaesthesia, in both groups. Also, we observed no statistical difference between the propofol and thiopental–sevoflurane groups. These findings suggest that the BP-lowering actions of propofol and sevoflurane in human subjects during anaesthesia cannot be attributed to an enhancement of NO synthesis (sum of nitrite and nitrate) or NO bioavailability (nitrite).

Figure 1.

Nitrite (NO2) and nitrate (NO3) plasma concentrations during the first hour (0, 10, 30 and 60 min) of general anaesthesia with either propofol (P, n = 18) or thiopental/sevoflurane (S, n = 14). Data are shown as mean values ± SEM. Two-tailed Mann–Whitney U-test was used to test statistical significance. None of the comparisons yielded statistical significance between the groups (P > 0.05)

Isoflurane, another anaesthetic of the flurane group, and pentobarbital, but not ketamine, have been very recently shown to lower BP and to protect the heart in a rat model of stress-induced cardiomyopathy (takotsubo cardiomyopathy) 13. Thus, interaction of fluranes with adrenergic signalling and inhibition of catecholamine-induced increase in contractility may explain both the BP-lowering and the cardioprotective effects of sevoflurane. Hypotension during propofol or sevoflurane anaesthesia may result from several different mechanisms. Taking into consideration that anaesthetics such as propofol may alter the pharmacokinetics of other co-administered drugs, such as midazolam, may help in the design of mechanistic studies to provide better understanding of the pharmacodynamic effects resulting from drug–drug interactions 14. Ultimately, anaesthetics such as propofol and sevoflurane may also alter distribution, metabolism and elimination of endogenously produced compounds, resulting in enhancement or attenuation of their biological activities. The reduction of plasma anandamide during propofol or thiopental–sevoflurane anaesthesia may have arisen from drug-induced increase of the metabolism/elimination of anandamide or redistribution of anandamide between blood and other body compartments 9, presumably depending upon their lipophilicity/hydrophilicity. Propofol altered midazolam pharmacokinetics at plasma concentration of 1.2 mg l−1 14. In our previous study, the plasma propofol concentration was above this value and did not correlate with plasma anandamide concentration 9. An explanation for the lack of correlation between plasma anandamide and propofol concentrations may be that plasma propofol concentrations occurring during propofol anaesthesia are sufficient to enhance the metabolism/elimination of the lipophilic, neutral lipid anandamide upon starting anaesthesia, analogous to midazolam 9.

Elevated TxA2 synthesis 15,16 and diminished NO synthesis/bioavailability 6 are associated with hypertension. Inhibition of TxA2 synthesis and elevation of NO synthesis/bioavailability by drugs such as the widely used anaesthetics, including propofol, may lower BP. Published studies do not support the involvement of TxA2 in anaesthesia-induced hypotension. In the present study, we did not detect influences of propofol or thiopental–sevoflurane on NO synthesis/bioavailability in a sufficiently powered study employing a validated analytical method for measurement of nitrite and nitrate concentrations in human plasma. The BP-lowering effects of propofol or sevoflurane anaesthesia are likely to be mediated through inhibition of the sympathetic nervous system and impairment of baroreflex regulatory mechanisms.

Competing Interests

All authors have completed the Unified Competing Interest form at http://www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf (available on request from the corresponding author) and declare: no support from any organization for the submitted work; no financial relationships with any organizations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous 3 years; no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

References

- Trapani G, Altomare C, Liso G, Sanna E, Biggio G. Propofol in anesthesia. Mechanism of action, structure-activity relationships, and drug delivery. Curr Med Chem. 2000;7:249–271. doi: 10.2174/0929867003375335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krasowski MD, Jenkins A, Flood P, Kung AY, Hopfinger AJ, Harrison NL. General anesthetic potencies of a series of propofol analogs correlate with potency for potentiation of γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) current at the GABAA receptor but not with lipid solubility. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2001;297:338–351. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holaday DA, Smith FR. Clinical characteristics and biotransformation of sevoflurane in healthy human volunteers. Anesthesiology. 1981;54:100–106. doi: 10.1097/00000542-198102000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilton P, Dev VJ, Major E. Intravenous anaesthesia with propofol and alfentanil. The influence of age and weight. Anaesthesia. 1986;41:640–643. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.1986.tb13061.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebert TJ, Muzi M, Berens R, Goff D, Kampine JP. Sympathetic responses to induction of anesthesia in humans with propofol or etomidate. Anesthesiology. 1992;76:725–733. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199205000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsikas D, Gutzki FM, Stichtenoth DO. Circulating and excretory nitrite and nitrate as indicators of nitric oxide synthesis in humans: methods of analysis. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2006;62(Suppl. 13):51–59. [Google Scholar]

- Mendez D, De la Cruz JP, Arrebola MM, Guerrero A, González-Correa JA, García-Temboury E, Sánchez de la Cuesta F. The effect of propofol on the interaction of platelets with leukocytes and erythrocytes in surgical patients. Anesth Analg. 2003;96:713–719. doi: 10.1213/01.ANE.0000049691.56386.E0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirakata H, Nakamura K, Yokubol B, Toda H, Hatano Y, Urabe N, Mori K. Propofol has both enhancing and suppressing effects on human platelet aggregation in vitro. Anesthesiology. 1999;91:1361–1369. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199911000-00028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarzimski C, Karst M, Zoerner AA, Rakers C, May M, Suchy MT, Tsikas D, Krauss JK, Scheinichen D, Jordan J, Engeli S. Changes of blood endocannabinoids during anaesthesia: a special case for fatty acid amide hydrolase inhibition by propofol? Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2012;74:54–59. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2012.04175.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malinowska B, Baranowska-Kuczko M, Schlicker E. Triphasic blood pressure responses to cannabinoids: do we understand the mechanism? Br J Pharmacol. 2012;165:2073–2088. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2011.01747.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsikas D. Analysis of nitrite and nitrate in biological fluids by assays based on the Griess reaction: appraisal of the Griess reaction in the l-arginine/nitric oxide area of research. J Chromatogr B. 2007;851:51–70. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2006.07.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsikas D. Simultaneous derivatization and quantification of the nitric oxide metabolites nitrite and nitrate in biological fluids by gas chromatography/mass spectrometry. Anal Chem. 2000;72:4064–4072. doi: 10.1021/ac9913255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redfors B, Oras J, Shao Y, Seemann-Lodding H, Ricksten SE, Omerovic E. Cardioprotective effects of isoflurane in a rat model of stress-induced cardiomyopathy (takotsubo) Int J Cardiol. 2014;176:815–821. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2014.08.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lichtenbelt BJ, Olofsen E, Dahan A, van Kleef JW, Struys MM, Vuyk J. Propofol reduces the distribution and clearance of midazolam. Anesth Analg. 2010;110:1597–1606. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0b013e3181da91bb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzgerald DJ, Rocki W, Murray R, Mayo G, FitzGerald GA. Thromboxane A2 synthesis in pregnancy-induced hypertension. Lancet. 1990;335:751–754. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(90)90869-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sellers MM, Stallone JN. Sympathy for the devil: the role of thromboxane in the regulation of vascular tone and blood pressure. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2008;294:H1978–1986. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01318.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]