Abstract

We examined the impact of the Experience Corps® (EC) program on school climate within Baltimore City public elementary schools. In this program, teams of older adult volunteers were placed in high intensity (>15 hours per week), meaningful roles in public elementary schools, to improve the educational outcomes of children as well as the health and well-being of volunteers. During the first year of EC participation, school climate was perceived more favorably among staff and students in EC schools as compared to those in comparison schools. However, with a few notable exceptions, perceived school climate did not differ for staff or students in intervention and comparison schools during the second year of exposure to the EC program. These findings suggest that perceptions of school climate may be altered by introducing a new program into elementary schools; however, research examining how perceptions of school climate are impacted over a longer period is warranted.

Keywords: academic achievement, classroom behavior, childhood education, school climate, older adult volunteers

Given the considerable amount of time that children spend at school, the nature of the environment undoubtedly shapes their academic, social, and psychological development (Osher, Kendziora, Spier, & Garibaldi, 2014). Consequently, students are most likely to thrive in enriched, safe, and supportive environments, as opposed to those infused with conflict, tension, and delinquency. The term school climate refers to relatively enduring characteristics that capture the distinctive tone or atmosphere of an entire school (National School Climate Council, 2007; Thapa, Cohen, Guffey, & Higgins-D’Alessandro, 2013). Further, the perceptions that students, teachers, staff, and parents hold regarding the environmental qualities of the school can greatly impact the nature of their interactions and ability to benefit from the educational mission of the school system. These beliefs, values, and attitudes-whether based in reality or not-define the boundaries for acceptable individual behavior and instructional practice (Welsh, 2000).

Several studies have demonstrated the beneficial effects of a positive school climate on children’s educational motivation, classroom engagement, and school attendance (Brand, Felner, Shim, Seitsinger, & Dumas, 2003; MacNeil, Prater, & Busch, 2009; Sherblom, Marshall, & Sherblom, 2006; Stewart, 2008; Thapa et al., 2013), as well as with a reduction in student aggression, behavioral problems, and emotional distress (Kuperminc, Leadbeater, & Blatt, 2001; Loukas & Robinson, 2004; Shochet, Dadds, Ham, & Montague, 2006; Steffgen, Recchia, Viechtbauer, 2013; Wilson, 2004). Similarly, a healthy school climate positively impacts the performance of principals, teachers, and other school staff (Cohen, McCabe, Michelli, & Pickeral, 2009; Grayson & Alvarez, 2008), which in turn contributes to improved academic achievement and behavioral outcomes for the students (Bryk, Sebring, Allensworth, Luppescu, & Easton, 2010; Hambre & Pianta, 2001).

Early childhood intervention programs in elementary schools have been effective in increasing academic performance and reducing student misconduct and, therefore, may also serve as a means of creating a positive school climate (Bradshaw, Koth, Thornton, & Leaf, 2009; Durlak, Weissberg, Dymnicki, Taylor, & Schellinger, 2011). Unfortunately, and much too often, schools are underfunded and lack the organizational capacity or resources needed for successful implementation and sustainability of such programs. One model, Experience Corps® (EC), was designed to help fill unmet educational needs of elementary school children while simultaneously increasing physical, cognitive, and social activity -and through these activity pathways- impacting the health of older adult volunteers. In this intergenerational program, older adults were trained to perform roles to enhance academic performance and classroom behavior of children in public elementary schools. After training, volunteers were placed in Kindergarten through third grade classrooms to serve in meaningful roles determined by the schools’ principals and teachers as being critical to school success, including those related to literacy, mathematics, and behavioral self-management.

Several key design features of the Experience Corps program (e.g., intensive training, critical mass/teams, meaningful roles, infrastructure support) were expected to contribute to the program’s success in increasing children’s academic performance, reducing behavioral disruptions, and more broadly, improving school climate (Glass et al., 2004; Figure 1). Prior to entering the schools, volunteers were required to participate in an intensive, week-long training program (approximately 30 hours) consisting of lectures, group discussion, and role-playing exercises designed to prepare the volunteer for working with children (e.g., academic support, conflict resolution) and navigating the school environment. Once placed into the schools, volunteers committed at least 15 hours of service per week for a full academic year. During their service, most volunteers worked within a classroom setting, providing literacy and math support, as well as behavior management and conflict resolution skills. Thus, we hypothesized that volunteers would directly impact children’s academic and behavioral performance through face-to-face mentoring, tutoring, role-modeling, behavior management, and skill coaching (i.e., the “child building pathway”, see Figure 1) (Glass et al., 2004; Rebok et al., 2004).

Figure 1.

Hypothesized causal pathway of the Baltimore Experience Corps program effects on children and school outcomes (Figure adapted from Glass et al., 2004)

We also hypothesized that older adult volunteers could impact the entire school indirectly through a “social capital pathway” (Figure 1). To achieve this goal, organized teams of 10–15 older adult volunteers (i.e., critical mass) were placed in each school to fully “saturate” classrooms and become assimilated into the larger school environment (Fried et al., 2013; Glass et al., 2004; Rebok et al., 2004). Specifically, the number of volunteers needed for each school was determined with the goal of placing one to two volunteers in every Kindergarten through third grade classroom and adjusted after consultation with the school’s Principal to best meet the school’s needs.

By obtaining full coverage of all Kindergarten through third grade classrooms within a given school, we expected that this would increase the adult-to-child ratio, contributing to children’s academic success and calming of disruptive behaviors. In addition to working in specific classrooms, Experience Corps volunteers also assisted in the library, gymnasium, cafeteria, computer laboratory, and monitored the hallways; thereby, creating a strong and sustained presence throughout the school. Therefore, we anticipated that organized teams of volunteers would have the capacity and power to change norms and resources within and around the school, thus making a greater impact on the school and the broader community than would any single individual (Glass et al., 2004; Fried et al., 2013).

Prior findings from the Experience Corps pilot trial (Fall 1999 to Summer 2000; one academic year) indicated that older adult volunteers could positively impact school climate (Rebok et al., 2004). Within the three Experience Corps pilot schools studied, the number of referrals to the principal’s office for behavioral issues was reduced by 50% for two schools and by 34% for the third school; these school-level reductions in office referrals were not seen in the control schools. Other beneficial effects included improved teachers’ perceptions of classroom instruction, additional support for teachers, better interactions between children and adults, and improved school-community relations (Rebok et al., 2004; Rebok et al., 2009). These findings were consistent with our hypothesis that school climate would improve, more broadly, as a result of the infusion of social capital into the school (Glass et al., 2004).

Based on our promising pilot findings, a randomized-controlled trial of the Baltimore Experience Corps was conducted in partnership with the Greater Homewood Community Corporation (GHCC) and the Baltimore City Public School system. The Baltimore Experience Corps trial was designed to evaluate the effects of program participation for older adults, as well as children and schools over a two-year period. Because it was not feasible to randomize schools, classrooms, or children to the intervention, all randomization was done at the level of the older adult volunteers (N = 702), with 352 individuals randomized to participate in the Baltimore Experience Corps program and 350 referred to a usual low-activity control condition (see Fried et al., 2013 for full description of randomization procedures and study design). Further, because our capacity for training and placing volunteers into available schools was limited, older adults were recruited and randomized in four cohorts, spanning a five-year trial period (2006–2011). To be eligible for participation, volunteers had to be at least 60 years of age, by functionally literate at or above the 6th grade level (by WRAT-4), cognitively intact enough to be able to assist teachers and children in a safe and effective manner (based on Mini-Mental State Exam cutoff score of ≥24); and have passed the criminal background and alcohol breathalyzer tests required by the school system (see Fried et al., 2013; Rebok et al., 2014). Eligible older adults were randomly assigned to a usual low-activity control group or the Baltimore Experience Corps program (i.e., intervention). Those randomized to the intervention arm were trained and placed in a critical mass in an intervention school for a 2-year period. Our community partner, GHCC, was responsible for all pre-service and in-service training sessions and day-to-day administration of the intervention, including assignment of volunteers to schools, incident (adverse events) reports, and collecting weekly timesheets and volunteer activity logs. GHCC was also responsible for selecting, training, and placing a “team leader” (usually an experienced volunteer) in each school to supervise and support other volunteers. On average, volunteers’ spent approximately 13 hours per week (SD = 2.6 hours) for 44 weeks during the academic year engaged in various volunteer roles and school-based activities (e.g., individual academic support, reading to entire classroom, attending plays/concerts). Volunteers were, on average, 67.3 years of age, mostly female (86.9%), African-American (91.3%), and 53.7% had more than a high-school education (Ramsey, 2014).

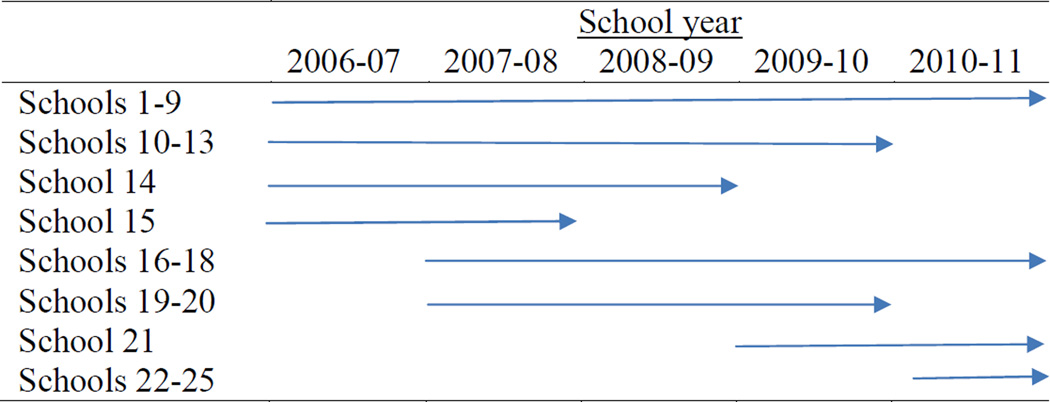

Baltimore City public elementary schools were also enrolled into the study in four waves across the 2006–2007 to 2010–2011 academic years. Unfortunately, because of community challenges (e.g., the Baltimore City Public School system wanted to expand EC into schools with the greatest needs) and political realities (e.g., continued city funding), we were unable to randomize schools to the intervention (Tan et al., 2013; see Methods section for a detailed description of our matching approach). Instead, principals had to decide if they wanted to implement the Experience Corps program in their school amidst limited funding and multiple competing programs and priorities. Ultimately, the final decision on whether a school initiated or terminated participation in the program (and hence the study) was not ours (Figure 2). It should also be noted that after the two-year evaluation period, schools and volunteers could continue participating in the National Experience Corps program, led by our community partner, Greater Homewood Community Corporation.

Figure 2.

School initiation and discontinuation of participation in the Baltimore Experience Corps program between the 2006–07 and 2010–11 school years

Using data from the Baltimore Experience Corps, the present study examines the impact of the intervention over a two-year evaluation period on school climate, as perceived by school staff (principals, administrative staff, teachers) and elementary school students.

Methods

Experience Corps and Matched Comparison Schools

During the course of the Baltimore Experience Corps trial, a total of 25 Baltimore City public elementary schools were enrolled into the two-year study in four waves across the 2006–2007 to 2010–2011 academic years. For any given year, the total number of enrolled schools varied slightly, with an average of 19 schools participating per year (Fried et al., 2013; Ramsey, 2014). Patterns of school initiation and discontinuation of the Experience Corps program across academic years are presented in Figure 2. All Experience Corps schools were successful in retaining a critical mass of volunteers (10–15 older adults) for the duration of program participation.

In addition, 25 matched comparison schools were selected from all eligible public elementary schools in Baltimore City. To identify the most appropriate comparison school for each EC school, a three-stage propensity score matching approach was implemented (Rosenbaum & Rubin, 1985). Schools that participated in the EC program before or during the trial period, as well as charter schools or academies were excluded from the pool of potential candidates. First, for each EC school, candidate schools with propensity scores that differed from the intervention school by less than 0.25 standard deviations (SD) were identified as a potential match. Second, within the sample of candidate schools, the top three closest matches for the Stanford 10 normal curve equivalent (NCE) reading score at Grade 2 were selected. If there were more than three candidate schools with a difference in propensity scores less than 0.25 SD, then the three with a minimum difference in propensity scores were selected. Third, a panel of experts on school academic performance selected the most appropriate match for each EC school from the top three candidates. An application of the matching algorithm resulted in a balance between intervention and comparison schools with respect to the distribution of observed covariates at baseline before EC program initiation for the intervention schools (i.e., Title 1 status, elementary school-level attendance rate, student mobility, school size, percent of students receiving free or reduced price lunch, and percent of African-American students) (all ps > 0.05; Table 1).

Table 1.

School-level demographic characteristics of Experience Corps and matched comparison schools during the first and second years of program participation

| Year 1 (N=25) | Year 2 (N=21) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EC | Comparison | Comparison-EC | EC | Comparison | Comparison-EC | ||

| N (%) or Mean 95% CI |

N (%) or Mean 95% CI |

Odds ratio or Difference 95% CI |

N (%) or Mean 95% CI |

Odds ratio or Difference 95% CI |

Odds ratio or Difference 95% CI |

||

| School type | 0.85 | 0.44 | |||||

| [0.23, 3.02] | [0.10, 1.87] | ||||||

| K-5 | 14 (56) | 15 (60) | 11 (52.4) | 15 (70.0) | |||

| K-8 | 11 (44) | 10 (40) | 10 (47.6) | 6 (30.0) | |||

| Title I | 1 | 1.58 | |||||

| [0.12, 8.31] | [0.16, 20.81] | ||||||

| ≥95% | 22 (88) | 22 (88) | 18 (85.7) | 19 (90.5) | |||

| <5% | 3 (12) | 3 (12) | 3 (14.3) | 2 (9.5) | |||

| Enrollment | 389.1 | 410.9 | 21.8 | 411.3 | 341.7 | −69.6 | |

| [322.0, 456.3] | [344.7, 477.1] | [−46.2, 89.7] | [353.8, 468.9] | [261.6, 421.8] | [−138.7, −0.6] | ||

| FARMS | 93.9 | 93.77 | −0.17 | 93.9 | 94.2 | 0.3 | |

| [93.6, 94.3] | [93.2, 94.3] | [−0.8, 0.5] | [93.5, 94.3] | [93.9, 94.6] | [−0.2, 0.8] | ||

| Student mobility | 38.1 | 37.5 | −0.6 | 37.7 | 38.1 | 0.4 | |

| [34.2, 42.1] | [32.3, 42.7] | [−6.9, 5.6] | [32.3, 43.1] | [34.5, 41.7] | [−4.0, 4.8] | ||

| Attendance rate | 93.9 | 93.8 | −0.2 | 94 | 94.2 | 0.3 | |

| [93.5, 94.3] | [93.2, 94.3] | [−0.8, 0.5] | [93.5, 94.4] | [93.8, 94.6] | [−0.2, 0.7] | ||

Note. Title 1 percentage is calculated by dividing the number of Title I students by the June net enrollment; FARMS refers to Free and Reduced Meal Service; student mobility is calculated by dividing the sum of entrants and withdrawals by the average daily membership

Measures

School Climate Survey: Baltimore City Public School System

School climate was assessed using a survey developed and implemented within the Baltimore City Public School System. Alternate versions of the school climate survey were developed and administered on an annual basis during the spring semester of each school year to students (for grades 3–5 and grades 6–12 (not used in this study)), parents (not used in this study), and school personnel (administrators, teachers, support staff). Respondents were asked to assess the characteristics and effectiveness of the educational environment (e.g., I feel safe at this school; school rules are strictly enforced; school provides an orderly atmosphere for learning) using a 4-point scale (1 = strongly disagree; 4 = strongly agree), or the extent of problems in particular areas (e.g., physical or verbal abuse) on a 4-point scale (1 = not a problem to 4 = serious problem). During the course of the trial, the school climate survey was administered in all schools within the Baltimore City Public School system, including all Experience Corps and matched comparison schools. Across schools and years of participation, survey response rates ranged from 49% to 76% for students and 50% to 59% for staff (DREAA, 2008, 2011). Additional details about the survey development and psychometric properties have been presented elsewhere (Melick, Feldman, & Wilson, 2008; Ramsey, 2014).

Because the EC intervention was implemented in elementary schools, we chose to exclude survey responses from parents and from students in grades 6–12 (middle/high school) and only evaluate school climate from the perspective of those in schools exposed to the EC program (i.e., students in grades 3–5 and school administration). Although volunteers were placed in Kindergarten through third grade classrooms, perceptions of school climate were not assessed before third grade. Further, information was not collected on staff or student demographics, including grade level, so we could not independently examine responses for third through fifth grade students or teachers in these grades, nor could we examine the characteristics of students and staff who did and did not complete the School Climate survey. It should be noted, however, that although the intervention was primarily targeted at Kindergarten through third grade classrooms, older adults were placed in meaningful roles throughout the schools (e.g., library, computer room, gymnasium, hall/cafeteria monitor) and volunteered in the schools over multiple school years. Therefore, students in higher grades and all members of the school community may have received some level of exposure to the Experience Corps intervention.

For analysis of the staff survey responses, we examined overall school climate and nine sub-domains for each academic year (2006–2007 through 2010–2011). Cronbach’s alpha is presented as the range of reliability coefficients across this period. Specifically, the sub-domains of school climate included: school safety (12-items; e.g., I feel safe at this school, Fighting is not a problem at my school: α = 0.90 to 0.94), physical environment (7-items; e.g., The school building is clean and well maintained, There are a lot of broken windows, doors, or desks at this school: α = 0.55 to 0.78), learning environment (12-items; e.g., Students get along well with teachers, This school has clearly defined rules and expectations for students’ behavior: α = 0.83 to 0.87), teaching (7-items; e.g., Teachers care about their students, Teachers make expectations clear to students: α = 0.89 to 0.91), school satisfaction (6-items; e.g., I like my school/ I enjoy working at my school: α = 0.86 to 0.88), parental involvement and communication (6-items: e.g., Parents or guardians are welcome at this school, I have enough opportunity to talk with parents about students' progress or problems: α = 0.84 to 0.86), educational values (3-items; e.g., This school does a good job of educating students: α = 0.97 to 0.98), academic and behavioral resources (8-items; e.g., Students have enough school supplies, The school has clear procedures for getting help for students with suspected learning problems: α = 0.82 to 0.89), and school administration (6-items; e.g., School administration supports the staff in performing their duties, The school administration works collaboratively with staff to solve problems: α = 0.93 to 0.95) from the perspective of school staff.

For analysis of student (Grades 3–5) survey responses, overall school climate and four climate sub-domains were examined: school safety (7-items; α = 0.72 to 0.80), learning environment (5-items; α = 0.59 to 0.87), school satisfaction (5-items; α = 0.71 to 0.76), and educational values (3-items; α = 0.71 to 0.73). Sub-domains for teaching, academic and behavioral resources and school administration were not assessed in the student version of the Baltimore City Public School Climate survey, and physical environment and parental involvement and communication were excluded from the student analyses due to the low reliability (α < 0.50) of these measures (Nunnally & Bernstein, 1994). Scores for each sub-domain of school climate were obtained by taking the mean response of the items in each specific domain.

Data Analysis

The Baltimore Experience Corps trial was designed to evaluate the effects of participation in the program on older adults, children, and schools over a two-year evaluation period (Fried et al., 2013). The current analyses relied on school climate data collected during the first two years of Experience Corps participation, depending on the academic year in which the school was enrolled into the program (Figure 2). Specifically, multi-level models were used to examine mean student and staff ratings of school climate between EC intervention and comparison schools over the two-year evaluation period. The multi-level models included fixed effects for time (i.e., school year), the interaction terms between years of Experience Corps participation (1 or 2 years) and intervention status (0 = comparison; 1 = intervention), and random intercepts for schools. To obtain the most robust standard error estimates, we specified an exchangeable covariance model with a restricted maximum likelihood estimator (Diggle, Heagerty, Liang, & Zeger, 2002). Separate models were specified for each dimension of school climate. All statistical analyses were performed using Stata software, Version 13 (StataCorp, College Station, TX).

Results

Characteristics of Experience Corps and Matched Comparison Schools

Table 1 compares demographic characteristics of the 25 Experience Corps schools and matched comparison schools during the first year of participation in the study. Schools were predominantly low income, as indicated by the high proportion of students receiving free or reduced price meals (FARMS; >93%) and Title 1 status (>95%). Across schools, mean student enrollment was around 400 students, annual student mobility was approximately 38%, and average daily attendance rates were about 93–94%. No significant differences were found between Experience Corps and comparison schools for any of the demographic characteristics.

Staff and Student (Grades 3–5) Perceptions of School Climate

Descriptive statistics (e.g., means, SDs) for the school climate measure are presented by year of program participation and study condition (Experience Corps vs. matched comparison school) in Table 2. Table 3 compares school climate scores between schools enrolled in the Experience Corps program with the propensity score matched comparison schools for the first and second year of participation in the Experience Corps program. Findings for both staff and student (Grades 3–5) school climate perceptions are presented and discussed in detail below.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics for the Baltimore City School Climate measure for Experience Corps and matched comparison schools during the first and second years of program participation

| Year 1 | Year 2 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EC | Comparison | EC | Comparison | ||||||

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | ||

| Staff | |||||||||

| Overall climate | 3.18 | 0.22 | 3.05 | 0.16 | 3.13 | 0.16 | 3.10 | 0.16 | |

| Sub-domains | |||||||||

| School safety | 3.17 | 0.26 | 3.05 | 0.22 | 3.09 | 0.22 | 3.01 | 0.22 | |

| Learning environment | 2.94 | 0.28 | 2.83 | 0.21 | 2.92 | 0.17 | 2.82 | 0.20 | |

| School satisfaction | 3.33 | 0.26 | 3.17 | 0.23 | 3.28 | 0.20 | 3.26 | 0.21 | |

| Parental involvement | 3.24 | 0.21 | 3.12 | 0.17 | 3.19 | 0.13 | 3.16 | 0.18 | |

| Physical environment | 2.60 | 0.25 | 2.79 | 0.36 | 2.72 | 0.31 | 2.75 | 0.24 | |

| Educational values | 3.72 | 0.11 | 3.64 | 0.16 | 3.67 | 0.12 | 3.69 | 0.09 | |

| Resources | 2.92 | 0.27 | 2.78 | 0.22 | 2.92 | 0.20 | 2.87 | 0.22 | |

| Teaching | 3.33 | 0.21 | 3.23 | 0.17 | 3.26 | 0.13 | 3.25 | 0.14 | |

| School administration | 3.22 | 0.29 | 3.04 | 0.23 | 3.16 | 0.22 | 3.12 | 0.25 | |

| Students, Grades 3–5 | |||||||||

| Overall climate | 3.27 | 0.18 | 3.24 | 0.16 | 3.13 | 0.13 | 3.13 | 0.14 | |

| Sub-domains | |||||||||

| School safety | 2.94 | 0.05 | 2.93 | 0.06 | 2.88 | 0.28 | 2.85 | 0.31 | |

| Learning environment | 3.28 | 0.31 | 3.19 | 0.26 | 3.01 | 0.16 | 3.00 | 0.19 | |

| School satisfaction | 3.13 | 0.22 | 3.14 | 0.16 | 3.09 | 0.17 | 3.09 | 0.13 | |

| Educational values | 3.69 | 0.09 | 3.70 | 0.11 | 3.71 | 0.08 | 3.69 | 0.08 | |

Note. Characteristics and effectiveness of the educational environment (e.g., I feel safe at this school; school rules are strictly enforced; school provides an orderly atmosphere for learning) were rated on a 4-point scale (1 = strongly disagree; 4 = strongly agree). For physical environment, the extent of problems in particular areas (e.g., physical or verbal abuse) were rated a 4-point scale (1 = not a problem to 4 = serious problem).

Table 3.

Multi-level models comparing school climate between Experience Corps and matched comparison schools during the first and second years of program participation

| Year 1 | Year 2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| β (SE), p -value | β (SE), p -value | ||

| Staff | |||

| Overall climate | 0.10 (0.04), 0.01 | 0.07 (0.04), 0.12 | |

| Sub-domains | |||

| School safety | 0.09 (0.05), 0.08 | 0.11 (0.06), 0.10 | |

| Learning environment | 0.09 (0.05), 0.07 | 0.06 (0.06), 0.34 | |

| School satisfaction | 0.15 (0.05), <0.01 | 0.07 (0.06), 0.29 | |

| Parental involvement | 0.09 (0.04), 0.02 | 0.06 (0.05), 0.24 | |

| Physical environment | 0.08 (0.06), 0.13 | 0.08 (0.07), 0.24 | |

| Educational values | 0.07 (0.03), 0.01 | 0.06 (0.03), 0.06 | |

| Resources | 0.09 (0.05), 0.08 | 0.04 (0.06), 0.56 | |

| Teaching | 0.11 (0.03), <0.01 | 0.09 (0.04), 0.03 | |

| School administration | 0.17 (0.06), <0.01 | 0.07 (0.07), 0.33 | |

| Students, Grades 3–5 | |||

| Overall climate | 0.09 (0.03), 0.01 | 0.06 (0.04), 0.17 | |

| Sub-domains | |||

| School safety | 0.10 (0.06), 0.08 | 0.11 (0.07), 0.15 | |

| Learning environment | 0.13 (0.05), 0.01 | 0.01 (0.06), 0.83 | |

| School satisfaction | 0.01 (0.03), 0.68 | 0.004 (0.04), 0.92 | |

| Educational values | 0.01 (0.02), 0.78 | 0.05 (0.02), 0.04 | |

Staff perceptions

During the first year of participation in the EC program, on average, dimensions of school climate (teaching, administration, parental involvement and communication, educational values, and overall satisfaction), as well as overall school climate (β=0.10, SE =0.04, p = 0.01), were perceived more favorably among staff in EC schools as compared to staff in comparison schools (all ps <0.05; Table 2). During the second year of the program, perceptions of teaching were also found to be favorably perceived (p < 0.05); however, no other findings reached significance (all ps > 0.05).

Student perceptions

During the first year of participation in the EC program, on average, overall school climate (β = 0.09, SE = 0.03, p < 0.01), as well as the learning environment dimension of school climate (β = 0.13, SE = 0.05, p < 0.01), were perceived more favorably among students in EC schools as compared to students in comparison schools (Table 2). In the second year, EC schools had higher ratings on educational values compared to comparison schools (β = 0.05, SE = 0.02, p = 0.044); no other significant differences were found between intervention and comparison schools on any other school climate dimension.

Discussion

Within the context of the Baltimore City Experience Corps trial, teams of older adults were placed into elementary schools to assist teachers in the classroom, impact academic and behavioral outcomes for children, and bring about changes in the organizational climate of the school (Fried et al., 2013; Glass et al., 2004; Rebok et al., 2004; see Figure 1). During the first year of Experience Corps participation, overall school climate, as well as several independent dimensions of school climate, were perceived more favorably among staff (principals, administrative staff, teachers) and students (grades 3–5) in EC schools as compared with those in comparison schools. With a few notable exceptions, however, perceptions of school climate did not differ between staff or students in intervention and comparison schools during the second year of exposure to the EC program. Notably, staff ratings of teaching and student ratings of educational values were higher in EC schools than for comparison schools during the second year of participation, as well as in Year 1. These areas are often listed among the most important for positively impacting school climate and influencing student achievement (Hoy & Hannum, 1997; Zullig, Huebner, & Patton, 2011). Our findings are also consistent with research suggesting that teachers’ perceptions are more sensitive to classroom-level factors (e.g., teaching), whereas students’ perceptions are sensitive to school-level factors (e.g., educational values) (Mitchell, Bradshaw, & Leaf, 2010).

These results are not completely surprising; although they need to be interpreted cautiously as examining multiple dimensions of school climate increases the likelihood of detecting an effect that is not truly present (i.e., Type 1 error). With that said, it is quite plausible that the greatest impact on perceptions of school climate would happen immediately after implementation of the Experience Corps program, but lessen as the novelty of the program diminishes over time. During the second year of the program, staff and students may only perceive changes in dimensions of school climate directly targeted by the EC program or for those dimensions in which they have personally experienced a notable difference in the conduct of the classroom or school.

The ability to alter perceptions of school climate is not trivial. Even if perceptions of school climate do not change much on the standardized climate measure, this is not to say that the Experience Corps program is ineffective. Successful implementation of the program could impact other important school-based outcomes (e.g., academic achievement, teacher retention, attendance), in turn, impacting school climate. In addition, as our results are based on data aggregated across schools, it is possible that some schools show reliable (and potentially stronger) effects at Year 2 compared to Year 1. Although we carefully measured and monitored the fidelity of the training sessions (e.g., standardized training manuals, knowledge assessments) and implementation of the program (e.g., tracked weekly hours and volunteer activities, weekly team meetings, classroom observations), there were other administrative and contextual changes that we were unable to capture, including changes in leadership, the extent of administrative support for the program, volunteer effectiveness, and other programs being conducted within the schools. Further research with a larger sample of schools, more comprehensive measurement of fidelity (especially at the contextual level), and closer examination of potential mediators or moderators of intervention effects on school climate is needed.

Several studies have also demonstrated that changing the climate of schools or other organizations is difficult to achieve. For instance, developers of the Positive Behavioral Intervention and Supports (PBIS) program, a universal, school-wide prevention program designed to reduce disruptive behavioral problems hypothesized that the intervention would take approximately 3–5 years post-implementation to demonstrate any measurable impact on school climate (Sugai & Horner, 2006). However, creating even the slightest shift towards a more positive school environment may contribute to a host of other academic and behavioral benefits for students (Gottfredson et al., 2005; Hamre & Pianta, 2001; Hoy & Hannum, 1997), as well as greater satisfaction and increased retention among teachers (Grayson & Alvarez, 2008; Maslach & Jackson, 1981). Moreover, creating a positive school environment may be even more important for large, urban elementary schools, such as Baltimore City Public Schools. Elementary schools with high proportions of students with low socioeconomic status (SES) tend to report measures indicating worse school climate and are associated with higher rates of teacher turnover (Cohen et al., 2009; Guin, 2004). However, some studies have found that improving school climate may mitigate the negative impact of the socioeconomic context on academic success (Astor, Benbenisty, & Estrada, 2009). In this light, the findings over the first two years of perceived improvements in key elements of school climate are an encouraging intermediate measure of positive impact of Experience Corps on schools.

These findings, however, need to be presented along with several limitations. First, the school climate survey was developed for the Baltimore City Public School System and, to date, has not been tested or validated in other school districts, and thus the generalizability of our findings to similar large urban school districts may be limited. However, while the specific measures may vary across school systems, the core elements impacted by Experience Corps volunteers is presumed to translate to a more cohesive and organized school climate (Fried et al., 2013; Osher et al., 2014). Second, although it would be ideal to examine school climate from the perspective of children most likely impacted by the program (K-3); unfortunately, the school climate survey was administered by the Baltimore City Public School system to students starting in the 3rd grade and data are unavailable at earlier grade levels. Data on grade level were also unavailable; therefore, we cannot analyze grades 3, 4, and 5 separately (for both student and staff responses), which may actually underestimate any expected benefits of Experience Corps program. Related to this point, in order to maintain anonymity of respondents, no identifying information was collected; therefore, we cannot ascertain whether measures were completed by the same individuals during the first and second assessment periods. As a result, inconsistencies in staff and student perceptions for Years 1 and 2 may actually reflect typically high rates of turnover and our limited ability to draw inferences regarding how school climate is impacted over time. Without this information, we also could not assess the extent of missingness with regard to individual-level response rates. For analysis, we made the assumption that survey non-response rates did not differ with respect to student and staff perceptions of school climate (i.e., data were missing completely at random). Although we recognize that this may not be the case, random effects models (used for our analysis) tend to be robust to data missing at random. We also accounted for school/student characteristics that are potentially predictive of missing responses in our analytic approach. Lastly, we were unable to determine whether there were other contextual changes at the school level, such as changes in administration or the implementation of other initiatives, and the impact that these changes may have had on our findings.

One of our greatest lessons learned was how critical it is to have a strong commitment from school administration and dedicated community partners (Greater Homewood Community Corporation and Baltimore City Public School system) for successful implementation of a school-based, community program (Rebok et al., 2014; Tan et al., 2013). During the design and implementation of Experience Corps, we encountered many political and community realities of conducting research in the “real world”. For instance, although it would have been ideal to randomize at both the older adult- and the school-level, this was not possible. We also faced initial challenges during implementation as schools often lacked the organizational capacity and resources needed to fully support the Experience Corps program and volunteers (Tan et al., 2013). Most relevant to the current study, because of different missions and expectations between key stakeholders, it was not possible to collect data on school climate from children in earlier grades or to collect descriptive information along with the survey administration. As a result, we were unable to examine data for those who were most likely impacted by the program, thereby potentially underestimating the effects of the Experience Corps. We were also unable to collect school-level characteristics, which can also affect the standardization and fidelity of program implementation. Although we faced some challenges, working in true partnership with a community-based organization who was able to provide support, resources, and the infrastructure for Experience Corps allowed us to “scale-up” and successfully implement the program in several “hard-to-reach” schools. The lessons learned through our academic-community partnership may serve as a guide for expansion of other school and community-based public health programs (see Tan et al., 2013 for full review).

Gaining a better understanding of how staff and students perceive school climate may offer potential targets for prevention and intervention (Cohen & Syme, 2013). Introducing programs, such as Experience Corps, may help create a supportive environment, in which staff and students feel safe, motivated, and supported. Although the exact mechanisms are unknown, our findings suggest that Baltimore City Experience Corps volunteers make a difference in the lives of teachers and students. By having older adult volunteers assist with various classroom and school activities, staff may feel less burdened and more supported. In addition, volunteers may help keep classrooms more organized and orderly, thereby creating an environment in which teachers have more time to focus on teaching activities or appropriately deal with disruptive situations. As a result, children might be more engaged in the learning process, resulting in increased academic performance. Likewise, children may feel safer with additional adults monitoring the school hallways. These promising initial findings call for the value of future work to link school climate with children’s academic and behavioral outcomes. Also, following upon the latent impact observed for other programs, such as the PBIS (Sugai & Horner, 2006; Bradshaw et al., 2009), longer-term follow-up is warranted to determine how climate is impacted with longer duration of exposure to the EC program.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by funding from the following sources: the National Institute on Aging (P01 AG027735-03), the Weinberg Foundation, and state and federal AmeriCorps grants. We would also like to thank the Baltimore City Public School System for all of their efforts in helping us acquire and interpret the academic and behavioral outcomes data.

Dr. Erwin J. Tan is with the Corporation for National and Community Service. This manuscript represents work done while Dr. Tan was at the Johns Hopkins Center on Aging and Health. The opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not represent the official position of the Corporation for National and Community Service.

Footnotes

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- Astor RA, Benbenisty R, Estrada JN. School violence and theoretically atypical schools: The principal’s centrality in orchestrating safe schools. American Educational Research Journal. 2009;46:423–461. [Google Scholar]

- Bradshaw C, Koth C, Thornton L, Leaf P. Altering school climate through school-wide positive behavioral interventions and supports: Findings from a group-randomized effectiveness trial. Prevention Science. 2009;10:100–115. doi: 10.1007/s11121-008-0114-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brand S, Felner R, Shim M, Seitsinger A, Dumas T. Middle school improvement and reform: Development of validation of a school-level assessment of climate, cultural pluralism and school safety. Journal of Educational Psychology. 2003;95:570–588. [Google Scholar]

- Bryk AS, Sebring PB, Allensworth E, Luppescu S, Easton JQ. Organizing schools for improvement: Lessons from Chicago. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen AK, Syme SL. Education: A missed opportunity for public health intervention. American Journal of Public Health. 2013;103:997–1001. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.300993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J, McCabe EM, Michelli NM, Pickeral T. School climate: Research, policy, teacher education and practice. Teachers College Record. 2009;111:180–213. [Google Scholar]

- Diggle PJ, Heagerty P, Liang K, Zeger SL. Analysis of longitudinal data. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Division of Research, Evaluation, Assessment and Accountability (DREAA): Office of Achievement and Accountability. School year 2006–2007 School Climate Survey data: Students, parents and staff. Baltimore City Public School System; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Division of Research, Evaluation, Assessment and Accountability (DREAA): Office of Achievement and Accountability. School year 2009–2010 School Climate Survey data: Students, parents and staff. Baltimore City Public School System; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Durlak JA, Weissberg RP, Dymnicki AB, Taylor RD, Schellinger KB. The impact of enhancing students’ social and emotional learning: A meta-analysis of school based universal interventions. Child Development. 2011;82:405–432. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01564.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fried LP, Carlson MC, McGill S, Seeman T, Xue QL, Frick K, Rebok GW. Experience Corps: A dual trial to promote the heath of older adults and children’s academic success. Contemporary Clinical Trials. 2013;30:1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2013.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glass TA, Freedman M, Carlson MC, Hill J, Frick KD, Ialongo N, Fried LP. Experience Corps: Design of an intergenerational program to boost social capital and promote the health of an aging society. Journal of Urban Health. 2004;81:94–105. doi: 10.1093/jurban/jth096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottfredson GD, Gottfredson DC, Payne AA, Gottfredson NC. School climate predictors of school disorder: Results from a national study of delinquency prevention in schools. Journal of Research in Crime & Delinquency. 2005;42:412–444. [Google Scholar]

- Grayson L, Alvarez H. School climate factors relating to teacher burnout: A mediator model. Teaching and Teacher Education. 2008;24:1349–1363. [Google Scholar]

- Guin K. Chronic teacher turnover in urban elementary schools. [Retrieved [5/24/2012]];Education Policy Analysis Archives. 2004 12(42) from http://epaa.asu.edu/epaa/v12n42. [Google Scholar]

- Hamre BK, Pianta RC. Early teacher-child relationships and the trajectory of children’s school outcomes through eighth grade. Child Development. 2001;72:625–638. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoy WK, Hannum JW. Middle school climate: An empirical assessment of organizational health and student achievement. Educational Administration Quarterly. 1997;33:290–311. [Google Scholar]

- Kuperminc GP, Leadbeater BJ, Blatt SJ. School social climate and individual differences in vulnerability to psychopathology among middle school students. Journal of School Psychology. 2001;39:141–159. [Google Scholar]

- Loukas A, Robinson S. Examining the moderating role of perceived school climate in early adolescent adjustment. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2004;14:209–233. [Google Scholar]

- MacNeil AJ, Prater DL, Busch S. The effects of school culture and climate on student achievement. International Journal of Leadership in Education. 2009;12:73–84. [Google Scholar]

- Maslach C, Jackson SE. The measurement of experienced burnout. Journal of Occupational Behaviour. 1981;2:99–113. [Google Scholar]

- Melick C, Feldman B, Wilson R. SY07-08 School climate data: Students, parents, and staff. 2008 Retrieved from: http://www.baltimorecityschools.org. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell MM, Bradshaw CP, Leaf PJ. Student and teacher perceptions of school climate: A multilevel exploration of patterns of discrepancy. Journal of School Health. 2010;80:271–279. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2010.00501.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National School Climate Council. The School Climate Challenge: Narrowing the gap between school climate research and school climate policy, practice guidelines and teacher education policy. 2007 Retrieved from: www.schoolclimate.org/climate/advocacy.php. [Google Scholar]

- Nunnally JC, Bernstein IH. Psychometric theory. 3rd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Osher D, Kendziora K, Spier E, Garibaldi ML. School influences on child and youth development. In: Sloboda Z, Petras H, editors. Advances in prevention science, Volume 1: Defining prevention science. New York, NY: Springer; 2014. pp. 151–170. [Google Scholar]

- Ramsey CM. Doctoral dissertation. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University; 2014. School climate, older adult characteristics, and fulfillment of school-based volunteer roles in the Baltimore Experience Corps study. [Google Scholar]

- Rebok GW, Carlson MC, Frick KD, Giuriceo KD, Gruenewald TL, McGill S, Fried LP. The Experience Corps®: Intergenerational interventions to enhance well-being among retired people. In: Huppert FA, Cooper CL, editors. Wellbeing: Volume VI. Interventions and policies to enhance wellbeing. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell; 2014. pp. 307–330. [Google Scholar]

- Rebok GW, Tan E, Xue Q-L, Wang T, Lu Q. Child and school evaluation of the Baltimore Experience Corps® program: 2007–2008 summary report for the Weinberg Foundation. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins Center on Aging and Health; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Rebok GW, Carlson MC, Glass TA, McGill S, Hill J, Wasik BA, Rasmussen MD. Short-term impact of Experience Corps participation on children and schools: Results from a pilot randomized trial. Journal of Urban Health. 2004;81:79–93. doi: 10.1093/jurban/jth095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenbaum PR, Rubin DB. Constructing a control group using multivariate matched sampling methods that incorporate the propensity score. American Statistician. 1985;39:33–38. [Google Scholar]

- Sherblom SA, Marshall JC, Sherblom JC. The relationship between school climate and math and reading achievement. Journal of Research in Character Education. 2006;4:19–31. [Google Scholar]

- Shochet IM, Dadds MR, Ham D, Montague R. School connectedness is an underemphasized parameter in adolescent mental health: Results of a community prediction study. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology. 2006;35:170–179. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp3502_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steffgen G, Recchia S, Viechtbauer W. The link between school climate and violence in school: A meta-analytic review. Aggression and Violent Behavior. 2013;18:300–309. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart EB. School structural characteristics, student effort, peer associations, and parental involvement: The influence of school and individual level factors on academic achievement. Education and Urban Society. 2008;40:179–204. [Google Scholar]

- Sugai G, Horner R. A promising approach for expanding and sustaining the implementation of school-wide positive behavior support. School Psychology Review. 2006;35:245–259. [Google Scholar]

- Tan EJ, McGill S, Tanner EK, Carlson MC, Rebok GW, Seeman TE, Fried LP. The evolution of an academic-community partnership in the design, implementation, and evaluation of Experience Corps® Baltimore City: A courtship model. The Gerontologist. 2013;54:314–321. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnt072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thapa A, Cohen J, Guffey S, Higgins-D’Alessandro A. A review of school climate research. Review of Educational Research. 2013;83:357–385. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson D. The interface of school climate and school connectedness and relationships with aggression and victimization. Journal of School Health. 2004;74:293–299. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2004.tb08286.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zullig K, Huebner ES, Patton JM. Relationships among school climate domains and school satisfaction. Psychology in the Schools. 2011;48:133–145. [Google Scholar]