Abstract

IMPORTANCE

Adult attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is prevalent but often unrecognized, in part because it tends to co-occur with other disorders such as substance use disorders. Cocaine use disorder is one such disorder with high co-occurrence of ADHD.

OBJECTIVE

To examine whether treatment of co-occurring ADHD and cocaine use disorder with extended-release mixed amphetamine salts is effective at both improving ADHD symptoms and reducing cocaine use.

DESIGN, SETTING, AND PARTICIPANTS

Thirteen-week, randomized, double-blind, 3-arm, placebo-controlled trial of participants meeting DSM-IV-TR criteria for both ADHD and cocaine use disorder conducted between December 1, 2007, and April 15, 2013, at 2 academic health center substance abuse treatment research sites. One hundred twenty-six adults diagnosed as having comorbid ADHD and cocaine use disorder were randomized to extended-release mixed amphetamine salts or placebo. Analysis was by intent-to-treat population.

INTERVENTIONS

Participants received extended-release mixed amphetamine salts (60 or 80 mg) or placebo daily for 13 weeks and participated in weekly individual cognitive behavioral therapy.

MAIN OUTCOMES AND MEASURES

For ADHD, percentage of participants achieving at least a 30% reduction in ADHD symptom severity, measured by the Adult ADHD Investigator Symptom Rating Scale; for cocaine use, cocaine-negative weeks (by self-report of no cocaine use and weekly benzoylecgonine urine screens) during maintenance medication (weeks 2–13) and percentage of participants achieving abstinence for the last 3 weeks.

RESULTS

More patients achieved at least a 30% reduction in ADHD symptom severity in the medication groups (60 mg: 30 of 40 participants [75.0%]; odds ratio [OR] = 5.23; 95% CI, 1.98–13.85; P < .001; and 80 mg: 25 of 43 participants [58.1%]; OR = 2.27; 95% CI, 0.94–5.49; P = .07) compared with placebo (17 of 43 participants [39.5%]). The odds of a cocaine-negative week were higher in the 80-mg group (OR = 5.46; 95% CI, 2.25–13.27; P < .001) and 60-mg group (OR = 2.92; 95% CI, 1.15–7.42; P = .02) compared with placebo. Rates of continuous abstinence in the last 3 weeks were greater for the medication groups than the placebo group: 30.2% for the 80-mg group (OR = 11.87; 95% CI, 2.25–62.62; P = .004) and 17.5% for the 60-mg group (OR = 5.85; 95% CI, 1.04–33.04; P = .04) vs 7.0% for placebo.

CONCLUSIONS AND RELEVANCE

Extended-release mixed amphetamine salts in robust doses along with cognitive behavioral therapy are effective for treatment of co-occurring ADHD and cocaine use disorder, both improving ADHD symptoms and reducing cocaine use. The data suggest the importance of screening and treatment of ADHD in adults presenting with cocaine use disorder.

Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) often goes unrecognized and untreated1 and is associated with increased risk for cocaine use disorder (CUD)2 and other substance use disorders.3–5 It is observed in 2.5% to 4.0% of the general adult population6,7 and 10% to 24% of those seeking treatment for substance use disorders.8–10 The combination of ADHD and CUD is associated with poor outcome.11,12 While there are several agents for treatment of ADHD, there are no US Food and Drug Administration-approved medications for treatment of cocaine dependence.

Stimulant medications are effective for treatment of adult ADHD.13,14 However, previous studies on stimulant treatment for combined ADHD and CUD have been inconclusive. One factor may be inadequate dosage. It has been clinically observed that heavy cocaine users might require higher doses of stimulants to achieve a therapeutic effect.15,16 Amphetamines have shown promise in preliminary trials for treatment of cocaine dependence without co-occurring disorders.17,18 The abuse potential of a stimulant medication is of concern when considering treatment for cocaine dependence, but long-acting formulations with slow absorption and elimination mitigate this concern.19–21

We therefore conducted a randomized, placebo-controlled trial to determine the efficacy of extended-release mixed amphetamine salts in adults with ADHD and CUD. Two dosages of extended-release mixed amphetamine salts were tested: 60 mg/d because it has been the typical maximum dosage in trials of adults with ADHD,14,22 and 80 mg/d because it was hypothesized that a higher dosage might be needed in adults with ADHD and comorbid CUD owing to greater underlying dysregulation of dopamine transmission.23,24 It was hypothesized that extended-release mixed amphetamine salts would decrease ADHD symptoms and cocaine use in a dose-related fashion with greatest to least reductions with decreasing dose (80 mg > 60 mg > placebo).

Methods

Participants

Patients seeking treatment for CUD were recruited by local advertising for treatment research or clinical referrals. Advertisements mentioned reimbursement was provided for travel but did not mention other possible payments. Participants were enrolled at the Substance Treatment and Research Service of Columbia University/New York State Psychiatric Institute or at the Ambulatory Research Center, Department of Psychiatry, University of Minnesota.

Study inclusion criteria required the following: age 18 to 60 years, medically and psychiatrically stable, and meeting DSM-IV-TR diagnosis for current cocaine dependence and adult ADHD. Exclusion criteria were the following: past mania, schizophrenia, or any psychotic disorder other than transient psychosis due to drug abuse; current treatment, an unstable psychiatric or medical condition such as uncontrolled hypertension, or coronary vascular disease as indicated by history or suspected by abnormal electrocardiographic results, cardiac symptoms, fainting, open-heart surgery, and/or arrhythmia; and legally mandated to substance abuse treatment (eAppendix in Supplement 1 lists all inclusion and exclusion criteria).

Procedures

The study was approved by the institutional review boards of the New York State Psychiatric Institute and the University of Minnesota Academic Health Center. A data and safety monitoring board met yearly to review progress and safety. All participants provided written informed consent. Study enrollment occurred from December 1, 2007, through February 1, 2013, with study completion on June 28, 2013. The trial protocol is available in Supplement 2.

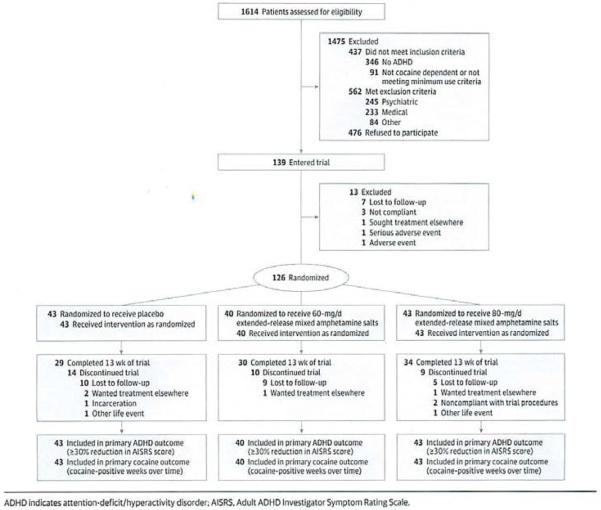

The study was a 3-arm, randomized, double-blind, parallel-group, 14-week trial comparing daily doses of extended-release mixed amphetamine salts (80 mg and 60 mg) and placebo (Figure 1; study timeline provided in the eFigure in Supplement 1). Randomization occurred at the end of a placebo lead-in phase (week 1) using a computer-generated fixed block size of 4, with a 1:1:1 allocation ratio, stratified by baseline cocaine use (self-report and/or positive urine screen for cocaine metabolite benzoylecgonine during week 1 [n = 109] vs no use [n = 17]). A PhD-level statistician at Columbia University maintained the allocation sequence and a PhD-level researcher at Columbia University and a pharmacist at the University of Minnesota conducted the randomizations independent of the research team. Participants, investigators, and study staff were blind to allocation.

Figure 1.

CONSORT Flow Diagram of Participants Through the Trial

Individuals were reimbursed for travel and given progressive vouchers for attendance at the clinic and following study procedures (eAppendix in Supplement 1).

Measures

Screening (prior to week 0) included a comprehensive psychiatric and medical evaluation, the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders,25 and Conners' Adult ADHD Diagnostic Interview for DSM-IV.26 The ADHD measures included the Adult ADHD Investigator Symptom Rating Scale (AISRS),27 collected biweekly, and Conners' Adult ADHD Rating Scale-Investigator Rated, Screening Version (CAARS),28,29 collected every 4 weeks. Additional ADHD measures included a weekly Clinical Global Impression improvement scale for ADHD.30

The timeline follow-back method31 at week 0 provided self-reported substance use 28 days prior and weekly throughout the study. Patients were scheduled to attend the clinic 3 times a week. Urine samples were obtained at each visit and tested for cocaine. Determinations of ADHD symptoms, medication adverse effects, clinical status, and medication adherence were made weekly (eTable 1 in Supplement 1 contains a schedule of assessments and procedures).

Interventions

A placebo lead-in period (week 1) preceded randomization followed by a 13-week trial with dose titrated in the first week and tapered down in the last week. Extended-release mixed amphetamine salts and placebo were packaged in identical capsules with approximately 100 mg of riboflavin. Adherence was measured from urine quantification of amphetamines (not available to study staff) and urine riboflavin fluorescence (available to study staff). Each week, all participants were provided with medication bottles under double-blind conditions. Participants unable to tolerate the maximum doses had their doses reduced based on clinical assessment. For example, if a participant noted insomnia or jitteriness, doses were reduced or suspended temporarily. Regular meetings were conducted with the physicians to discuss their approach to their clinical dosing decisions to ensure they were modifying doses in a consistent fashion.

All participants received cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT)/relapse prevention treatment32 weekly from experienced MA- or PhD-level therapists.

Safety Definitions and Analyses

Physical examinations including laboratory blood work were conducted at intake and week 14. Electrocardiograms were performed at screening and weeks 4, 8, and 14. Female participants had pregnancy tests performed at baseline and monthly during the study. Adverse effects were assessed weekly using the modified Systematic Assessment for Treatment Emergent Events.33 Vital signs were obtained at each study visit. Participants with blood pressure higher than 140/90 mm Hg or heart rate higher than 100 beats/min for 2 weeks or with single readings of blood pressure higher than 160/110 mm Hg or heart rate higher than 110 beats/min were discontinued from study medication. Adverse effects and adverse events were compared between groups using Fisher exact test.

Efficacy Definitions and Analyses

Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder

Percentage of participants achieving at least a 30% reduction in AISRS score from week 0 to week 12 (or last observation) was the primary outcome for ADHD.34,35 A secondary outcome was ADHD symptom improvement from week 0 to 14 (or last observation) assessed using the Clinical Global Impression scale (score of 1 [very much improved] or 2 [much improved]). If missing, these were imputed as not meeting the improvement threshold (n = 6). Other outcomes included Clinical Global Impression, AISRS, and CAARS rating changes from week 0 to the last observed measure. For 2 individuals missing the baseline CAARS rating, CAARS values were imputed as a random draw from the predicted distribution of week 0 CAARS values based on all participants' baseline characteristics. These ADHD outcomes were analyzed with logistic regression (primary and secondary outcomes) or linear regression (other ADHD measures), adjusting for week 0 cocaine use and AISRS score.

Cocaine Use Disorder

Each week after randomization was scored as cocaine positive, negative, or missing. A cocaine-abstinent week was defined as the following: (1) at least 2 urine drug screens collected and all collected urine samples (either 2 or 3) were cocaine negative; and (2) all self-reported cocaine use for the week was negative. A cocaine-positive week was defined as at least 1 positive result on the urine screen or positive self-report. For any day with both a qualitative urine screen or quantitative laboratory assessment collected, the quantitative assessment was used, with a benzoylecgonine level of 300 ng/mL or less considered negative. Weeks with insufficient data to determine use were designated as missing. The primary cocaine use outcome was the per-week designation of cocaine positive, negative, or missing. Proportion of participants with a cocaine-positive week was calculated per treatment group per week before and after imputing a cocaine-positive week for any individual with insufficient data in that particular week. Cocaine-positive weeks (without imputation) were analyzed using generalized estimating equations with a logistic link function, modeling use as a function of treatment (80 mg of extended-release mixed amphetamine salts vs 60 mg of extended-release mixed amphetamine salts vs placebo), time (trial week), and treatment-by-time interaction, with week 0 self-reported cocaine use for the past 28 days, week 1 cocaine-positive urine, and week 0 level of ADHD symptoms (AISRS score) as covariates. A second dichotomous outcome measure was cocaine abstinence for weeks 11 through 13. Individuals with insufficient data in these weeks were imputed as not abstinent. These data were analyzed using logistic regression as a function of treatment, adjusting for the same covariates.

Statistical Analysis

Baseline characteristics were summarized by treatment group using means, standard deviations, counts, and percentages as appropriate. Nonefficacy outcomes were retention, medication adherence (self-reported proportion of pills taken, staff-recorded urine qualitative riboflavin fluorescence, and laboratory-determined urine amphetamine level), and tolerability. Retention rates were compared across treatment groups using Kaplan-Meier curves and log-rank statistics. Nonparametric tests were used to compare measures of adherence across treatment groups.

All evaluations described in the preceding sections were conducted on the intent-to-treat sample of all randomized participants with missing data imputation as noted earlier and were 2-tailed with a significance level of 5%. We used PROCs GENMOD, LOGISTIC, and GLM in SAS statistical software (SAS Institute, Inc).36

Sufficient power (≥80%) for a 2-sided test with α = .05 for detecting differences between the 3 treatment arms for the primary ADHD and CUD outcome measures was predicated on 50 participants/treatment arm and 55% retention to maintenance phase end. While slightly fewer participants were randomized (40 in the 60-mg arm and 43 in the 80-mg and placebo arms), the retention rate of 73.8% was substantially higher than predicted.

Results

Participants

Screening of 1614 individuals yielded 126 participants meeting eligibility criteria who were randomized (Figure 1). Common reasons for nonrandomization included dropout prior to study entry or medical exclusions. The sample was predominantly male, unmarried, and unemployed. Approximately half of the participants were white and half were African American or Hispanic (eAppendix in Supplement 1). Baseline ADHD scores reflected moderate ADHD symptoms and the mean (SD) cocaine use at baseline was 11.65 (7.35) days/month (Table 1). Thirty-three participants (26.2%) dropped out prior to maintenance phase completion (end of week 13). Retention to week 13 was not significantly different among groups (80-mg group: 34 of 43 participants [79.1%]; 60-mg group: 30 of 40 participants [75.0%]; and placebo group: 29 of 43 participants [67.4%]; P = .51).

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics by Treatment Group

| Extended-Release Mixed Amphetamine Salts |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Placebo (n = 43) | 60 mg (n = 40) | 80 mg (n = 43) | P Value |

| Female, No. (%) | 5 (11.6) | 7 (17.5) | 8 (18.6) | .68 |

| Age, mean (SD), y | 39.26 (7.42) | 43.90 (7.45) | 38.37 (8.56) | .004 |

| Education, mean (SD), y | 13.49 (2.26) | 13.92 (2.46)a | 13.67 (2.81) | .74 |

| Race/ethnicity, No. (%) | ||||

| Hispanic | 10 (23.3) | 6 (15.0) | 6 (14.0) | |

| Black | 7 (16.3) | 9 (22.5) | 6 (14.0) | |

| White | 24 (55.8) | 21 (52.5) | 27 (62.8) | |

| Asian, Native American, and other | 2 (4.7) | 4 (10.0) | 4 (9.3) | |

| Marital status, No. (%) | ||||

| Currently married | 5 (12.2)b | 9 (22.5) | 7 (16.3) | |

| Not currently married | 36 (87.8)b | 31 (77.5) | 36 (83.7) | |

| Current employment, No. (%) | ||||

| Full-time | 14 (34.1)b | 10 (25.6)a | 17 (39.5) | |

| Part-time | 4 (9.8)b | 4 (10.3)a | 5 (11.6) | .71 |

| Unemployed | 23 (56.1)b | 25 (64.1)a | 21 (48.8) | |

| Baseline cocaine use through TLFB for 28 d up to wk 0, mean (SD), d/28 d | 11.28 (7.47) | 12.40 (7.76) | 11.33 (6.96) | .74 |

| Cocaine-positive urine screen at wk 1 | 39 (92.9)c | 35 (87.5) | 37 (86.0) | .60 |

| Alcohol dependence, No. (%) | ||||

| Current | 12 (27.9) | 8 (20.0) | 8 (18.6) | .54 |

| Lifetime | 23 (53.5) | 21 (52.5) | 21 (48.8) | .90 |

| Cannabis dependence, No. (%) | ||||

| Current | 6 (14.0) | 4 (10.0) | 3 (7.0) | .57 |

| Lifetime | 14 (32.6) | 12 (30.0) | 12 (27.9) | .90 |

| Current daily nicotine user, No. (%) | 28 (65.1) | 18 (45.0) | 21 (48.8) | .15 |

| Baseline AISRS score at wk 0, mean (SD) | 34.67 (9.83) | 35.85 (11.65) | 36.09 (11.04) | .81 |

| CAARS observer T-score, mean (SD) | ||||

| ADHD total | 69.19 (13.83) | 74.60 (13.37) | 71.06 (13.15) | .18 |

| Hyperactive | 68.72 (14.43) | 73.26 (14.01) | 70.40 (14.36) | .35 |

| Inattentive | 65.84 (13.43) | 70.64 (12.44) | 67.58 (13.79) | .25 |

Abbreviations: ADHD, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder; AISRS, Adult ADHD Investigator Symptom Rating Scale; CAARS, Conners' Adult ADHD Rating Scale; TLFB, timeline follow-back.

Based on n = 39 owing to missing data.

Based on n = 41 owing to missing data.

Based on n = 42 owing to missing data.

Treatment Adherence

Medication

Of those receiving extended-release mixed amphetamine salts, the mean (SD) tolerated dose was 53.3 (13.8) mg/d for the 60-mg group and 70.8 (18.3) mg/d for the 80-mg group. For the 121 participants completing induction, 65.9% of the 80-mg/d group, 65.0% of the 60-mg/d group, and 87.5% of the placebo group tolerated the assigned dose (; P = .04). Participant medication discontinuation rates were 12.2%, 17.5%, and 10.0% for the 80-mg, 60-mg, and placebo groups, respectively (; P = .60) due to intolerable adverse effects or to blood pressure or heart rate above strict study parameters.

Mean medication adherence as determined by self-reported pills taken was 98.8%, while median rates were not significantly different across groups (Kruskal-Wallis test, df = 2; P = .63). Median (interquartile range) percentages of samples that fluoresced for riboflavin were 100% (89.7%–100%) for the 80-mg group, 100% (95.4%–100%) for the 60-mg group, and 100% (92.9%–100%) for the placebo group (Kruskal-Wallis test, df = 2; P = .57). Median percentage of participants positive for amphetamine in the 60-mg and 80-mg groups was 90% (interquartile range, 70%–97%).

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy

Participants completed a mean (SD) of 8.9 (4.1) of 12 CBT sessions with no differences across groups. The mean (SD) numbers of CBT sessions per group were 9.1 (3.8) for the 80-mg group, 9.5 (4.0) for the 60-mg group, and 8.1 (4.4) for the placebo group (P = .27).

ADHD Outcome

All ADHD measures indicated greater improvement for active treatment (extended-release mixed amphetamine salts) compared with placebo (Table 2). The proportions of participants exhibiting at least a 30% reduction in AISRS score at the last enrollment week compared with week 0 were 58.1% (25 of 43) for the 80-mg group, 75.0% (30 of 40) for the 60-mg group, and 39.5% (17 of 43) for the placebo group, with odds ratios (ORs) of 2.27 (95% CI, 0.94–5.49; P = .07) for the 80-mg group vs placebo and 5.23 (95% CI, 1.98–13.85; P < .001) for the 60-mg group vs placebo. Similarly, the mean changes in ADHD ratings using the AISRS from week 0 to the last week of enrollment were clinically meaningful and significantly different for the 80-mg group compared with placebo as well as for the 60-mg group compared with placebo.

Table 2.

Outcomes for ADHD Separately by Treatment Groupa

|

P Value |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scale | Placebo (n = 43) | 60 mg (n = 40) | 80 mg (n = 43) | Placebo vs 60 and 80 mg | Placebo vs 60 mg | Placebo vs 80 mg | 60 vs 80 mg |

| AISRS | |||||||

| Score at last wk, mean (SD)b | 25.78 (13.94)c | 15.34 (12.93)d | 20.61 (14.22)c | ||||

| Last wk vs wk 0 | |||||||

| ≥30% Reduction, No. (%) | 17 (39.5) | 30 (75.0) | 25 (58.1) | .003 | <001 | .07 | .09 |

| Score change, mean (SD)e | 8.59 (12.24)c | 20.53 (13.18)d | 15.63 (10.93)c | <001 | <001 | .01 | .04 |

| CGI psychopathology subscale for ADHD, last wk vs wk 0 | |||||||

| Improvement, with score of ≤2, No. (%) | 5 (11.6) | 16 (40.0) | 15 (34.9) | .002 | .003 | .006 | .86 |

| Score change, mean (SD)e | 0.80 (1.23)c | 1.66 (1.17)d | 1.24 (1.11)c | .001 | <.001 | .03 | .20 |

| CAARS observer T-score, mean (SD) | |||||||

| Total | |||||||

| Score at last wk | 63.23 (15.77)f | 55.03 (15.56)g | 57.62 (14.70)h | ||||

| Score change at last wk vs wk 0e | 5.01 (12.84)f | 19.64 (16.33)g | 12.79 (13.53)h | <001 | <001 | .02 | .07 |

| Hyperactive | |||||||

| Score at last wk | 62.73 (17.12)f | 55.54 (16.83)g | 57.90 (13.42)h | ||||

| Score change at last wk vs wk 0e | 5.42 (14.92)f | 17.58 (14.71)g | 11.26 (12.47)h | .002 | <001 | .06 | .08 |

| Inattentive | |||||||

| Score at last wk | 60.65 (14.21)f | 53.11 (13.04)g | 55.28 (14.44)h | ||||

| Score change at last wk vs wk 0e | 4.03 (11.66)f | 17.75 (16.19)g | 12.18 (14.05)h | <001 | <001 | .02 | .15 |

Abbreviations: ADHD, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder; AISRS, Adult ADHD Investigator Symptom Rating Scale; CAARS, Conners' Adult ADHD Rating Scale; CGI, Clinical Global Impression.

The doses of 60 mg and 80 mg indicate the doses of extended-release mixed amphetamine salts per day. Statistical tests are adjusted for baseline cocaine use and for the week 0 measure of the ADHD scale (see Methods for details). Week 0 summaries are shown in Table 1.

The mean (SD) last weeks with nonmissing AISRS scores were the following: 9.49 (3.92) weeks for placebo, 10.18 (3.48) for 60-mg extended-release mixed amphetamine salts, and 10.47 (3.25) weeks for 80-mg extended-release mixed amphetamine salts.

Based on n = 41 owing to missing data.

Based on n = 38 owing to missing data.

Calculated as the value at week 0minus the value at the last week.

Based on n = 40 owing to missing data.

Based on n = 37 owing to missing data.

Based on n = 39 owing to missing data.

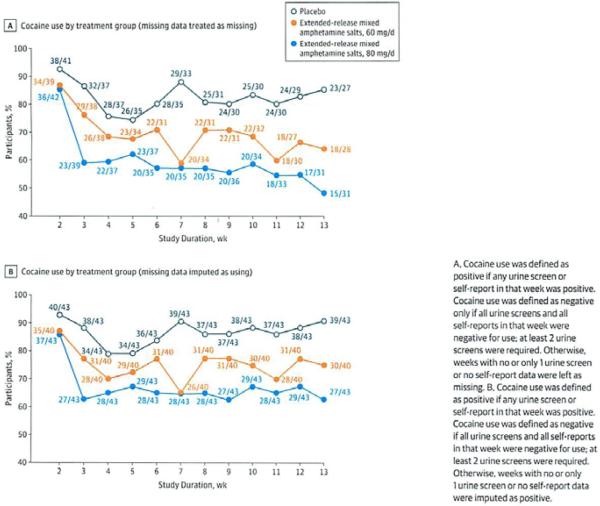

Cocaine Use Outcome

The highest dose of extended-release mixed amphetamine salts (80 mg) produced the greatest reduction in proportion of cocaine-positive weeks (determined through urine screens) throughout the study (Figure 2), regardless of whether missing weeks were coded positive or missing. There was a significant main effect of treatment, with higher cocaine abstinence in the 80-mg group over placebo (OR = 5.46; 95% CI, 2.25–13.27; P < .001) and in the 60-mg group over placebo (OR = 2.92; 95% CI, 1.15–7.42; P = .02). This was not different between the 80-mg and 60-mg groups (OR = 1.87; 95% CI, 0.86–4.05; P = .11). There was also a main effect of study week (P = .01) but no treatment-by-week interaction (P = .35), consistent with the similar spacing between groups across weeks in Figure 2. Pooled 60-mg and 80-mg groups vs placebo showed an OR of 4.08 (95% CI, 1.79–9.32; P < .001).

Figure 2.

Proportion of Participants With Cocaine Use by Randomized Treatment Group From Randomization (Week 2) Through End of Treatment Maintenance (Week 13)

The proportions with abstinence in the last 3 weeks were 30.2% (13 of 43) for the 80-mg group, 17.5% (7 of 40) for the 60-mg group, and 7.0% (3 of 43) for the placebo group, with ORs of 11.87 (95% CI, 2.25–62.62; P = .004) for the 80-mg group vs placebo and 5.85 (95% CI, 1.04–33.04; P = .04) for the 60-mg group vs placebo. Abstinence in the last 3 weeks was no different between the 80-mg and 60-mg groups (OR = 0.49; 95% CI, 0.16–1.53; P = .22). Pooled 60-mg and 80-mg groups vs placebo showed an OR of 8.74 (95% CI, 1.78–42.97; P = .008).

Adverse Effects and Adverse Events

Moderate to severe adverse events include insomnia and anxiety (eTable 2 in Supplement 1). Dry mouth was the only adverse event that occurred significantly more frequently in the groups receiving extended-release mixed amphetamine salts (P = .01). Two participants had serious adverse events requiring hospitalization: rape and pneumothorax. Both participants were receiving placebo and neither serious adverse event was deemed study related.

Discussion

In this trial, extended-release mixed amphetamine salts administered at robust doses along with CBT improved outcome in both ADHD symptoms and cocaine abstinence. As hypothesized, efficacy for CUD was dose related, with greatest abstinence for the group with the highest dosage (80 mg/d). While both 80 and 60 mg/d of extended-release mixed amphetamine salts compared with placebo produced substantial improvement in ADHD symptoms, the effect appeared somewhat greater at 60 mg. Consonant with the extensive ADHD literature and the smaller literature examining amphetamine analogues for stimulant dependence, the medication was well tolerated.17,22,37

Several reviews have examined whether psychostimulants reduce stimulant and other substance use in substance-dependent individuals. In a review of 16 studies targeting adults with cocaine dependence, Castells et al38 found that various types of psychostimulants (eg, mazindol, selegiline) did not reduce cocaine use but dextroamphetamine and bupropion might reduce cocaine use. Additionally, there have been 2 recent meta-analyses, one that evaluated stimulants and nonstimulant medications in substance-dependent individuals with ADHD39 and another that evaluated the efficacy of various psychostimulants in adults with amphetamine dependence.40 Neither found that psychostimulants reduced stimulant use among stimulant-dependent individuals with and without ADHD. However, only 4 of the 13 studies assessed in the review by Cunill et al39 evaluated stimulant-dependent individuals with ADHD with an amphetamine or methylphenidate product and only 4 of the 11 studies in the review by Pérez-Mañá et al40 evaluated amphetamine-dependent individuals with an amphetamine or methylphenidate formulation. These reviews are limited by the inclusion of studies that tested heterogeneous medications with different pharmacodynamic properties, reduced bioavailability of the medication formulations used, small sample sizes, or moderate dosing. Drawing conclusions based on the 3 reviews is further hampered since different patient populations were targeted. While our findings are promising and suggest that robust dosing of a long-acting amphetamine formulation reduces both ADHD symptoms and cocaine use, this needs to be viewed cautiously in the context of the extant literature and requires replication.

Notably, one placebo-controlled trial,41 not included in the aforementioned reviews, found methylphenidate effective for adults with co-occurring ADHD and a stimulant use disorder (amphetamine) using high doses (up to 180 mg), whereas the same research group found that a lower dose of methylphenidate (72 mg) was not effective in treating ADHD or amphetamine use disorder. This supports our hypothesis that robust doses of stimulant medication may be needed to treat adults with ADHD and co-occurring stimulant use disorders. While both methylphenidate and amphetamine prevent dopamine reuptake in mesolimbic pathways, amphetamines have additional effects, including inhibition of the vesicular monoamine transporter and direct dopamine release into the synapse, perhaps enhancing potency.42

The dose-effect finding for the cocaine use outcomes is consistent with other agonist replacement strategies (eg, methadone and buprenorphine for opioid dependence).43,44 For ADHD, the outcome was better for the medication arms than for placebo, with benefit possibly greater at the 60-mg dose rather than the 80-mg dose for some ADHD outcomes. This may be due to the sample size or could be because higher doses of amphetamine produced agitation or other ADHD-like symptoms, thereby obscuring its clinical benefit. Given that the higher dose is superior in promoting cocaine abstinence, in clinical practice it might be best to increase extended-release mixed amphetamine salts to the maximum tolerated dose and simultaneously assess ADHD symptoms and cocaine use to ensure maximum therapeutic benefit for both conditions.

Dosing is also germane to safety and clinical characteristics of active CUD prior to abstinence. Although we compared the maximum dosages of extended-release mixed amphetamine salts (80 mg/d and 60 mg/d) with placebo, dose reductions due to adverse effects or protocol-driven requirements to maintain systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, or heart rate below safety parameters resulted in lower mean tolerated doses: 53.3 mg for the 60-mg group and 70.8 mg for the 80-mg group. While there were no serious adverse cardiac or psychiatric effects in this trial or other trials examining amphetamine analogues for CUD, close monitoring of blood pressure, heart rate, cardiac symptoms, and psychiatric symptoms is prudent.

An important concern regarding agonist-like therapies in substance use disorders is potential misuse or diversion.16 This risk of abuse or diversion may be mitigated by using long-acting formulations lacking rapid absorption and elimination typical of the abused forms of addictive substances.42,45,46 Similar to other clinical trials of extended-release formulations of stimulants, there was no reported medication diversion or abuse.47,48 While self-report and biological measures indicated high levels of adherence to study medication dosing, we cannot assume that all participants were taking their medication as instructed.

A recent laboratory study of individuals who regularly used cocaine reported dose-related increases of liking for higher cocaine doses, but low and high doses of amphetamine produced only minimal drug liking.49 This critical finding suggests that oral amphetamine doses in the therapeutic range have lower reinforcing efficacy in individuals with stimulant use disorders, plausibly due to history, tolerance, or lower abuse potential of oral doses.

In addition to the risk of abuse or diversion, stimulant medications may worsen certain psychiatric conditions, such as bipolar disorder or schizophrenia. Clearly, any potential benefits need to be weighed against possible risks. However, as evidenced by this study, these risks can be managed in clinical practice by careful patient selection and setting.

High dropout is characteristic of clinical trials with cocaine-dependent patients. The dropout rate in the present trial was relatively low, perhaps owing to methodological features (eg, providing individual CBT and payments for attendance and for returning medication packaging) designed to improve adherence and retention.50,51 However, there were dropouts, and this does introduce uncertainty into the outcome assessment. Since all patients received CBT, we cannot conclude whether CBT is necessary to derive benefit from the medication. Because individuals with ADHD are a minority subgroup of cocaine users, and conversely only a fraction of patients with ADHD are cocaine dependent, it might seem that the generalizability is limited. However, many adults with ADHD have a history of substance abuse more generally, including nicotine, alcohol, or cannabis dependence,4,6,52 warranting further research in treating ADHD co-occurring with other substances. Moreover, since there remain no clearly effective medications for CUD53,54 and individuals with CUD are a heterogeneous population, an effective treatment among the subgroup with ADHD represents a substantial advance. Another future area of investigation would be to explore mediation models to understand how improvements of ADHD and CUD interact with each other (ie, whether there is greater CUD improvement with greater ADHD improvement).

Conclusions

In summary, this trial finds that (1) patients with ADHD and CUD benefit from treatment with extended-release mixed amphetamine salts combined with CBT; (2) exposure to extended-release mixed amphetamine salts produces a reduction in cocaine use; and (3) extended-release mixed amphetamine salts can be given safely to patients with CUD. Often, stimulants are withheld from individuals with co-occurring substance use disorders because of concern of diversion and clinical worsening. Instead, this study found the opposite– patients benefited from treatment. Thus, under closely monitored conditions, pharmacotherapy should be promoted, not barred. These data emphasize the importance of screening adults with CUD for ADHD. Future research might test long-acting stimulant formulations for other substance-abusing adult populations with ADHD, such as those with alcohol or cannabis use disorders.

Acknowledgments

Dr Levin reported receiving medication from US WorldMed for an ongoing study that is sponsored by the National Institute on Drug Abuse; serving as a consultant to GW Pharmaceuticals and Eli Lilly and Co from 2005 to 2007; serving on an advisory board to Shire in 2006 to 2007; and serving as a consultant to Major League Baseball regarding the diagnosis and treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Dr Nunes reported serving on an advisory board for Eli Lilly and Co in January 2012 and receiving medication from Alkermes for ongoing studies that are sponsored by the National Institute on Drug Abuse. Dr Grabowski reported serving on an advisory board to Shire in 2005 to 2007.

Funding/Support: This work was supported by grants R01DA 023651, R01DA 023652, KO2 000465, K24 DA029647, and K24 DA022412 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse.

Role of the Funder/Sponsor: The National Institute on Drug Abuse had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Additional Information: Drs Levin and Grabowski were principal investigators for the National Institutes of Health/National Institute on Drug Abuse-funded paired R01 grants at Columbia University and University of Minnesota, respectively, and are responsible for implementation and responsible conduct of the research projects.

Additional Contributions: Julie Whelan, MA, Department of Psychiatry, Medical School, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, contributed to data acquisition as well as administrative and technical support; she received no compensation. Martina Pavlicova, PhD, Columbia University, New York, New York, maintained the allocation sequence and Kenneth Carpenter, PhD, Columbia University, and Darlette Luke, BS, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, conducted the randomizations at the corresponding sites; they received no compensation. We acknowledge the contributions of the staffs of the Substance Treatment and Research Service at the New York State Psychiatric Institute and the Ambulatory Research Center, Department of Psychiatry, University of Minnesota.

TRIAL REGISTRATION clinicaltrials.gov Identifier: NCT00553319

Footnotes

Author Contributions: Drs Levin and Grabowski had full access to all of the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Study concept and design: Levin, Mariani, Nunes, Grabowski.

Acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data: All authors.

Drafting of the manuscript: Levin, Mariani, Brooks, Eberly, Nunes, Grabowski.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Levin, Mariani, Specker, Mooney, Mahony, Babb, Bai, Eberly, Nunes, Grabowski.

Statistical analysis: Brooks, Bai, Eberly, Nunes.

Obtained funding: Levin, Grabowski.

Administrative, technical, or material support: Levin, Mariani, Specker, Mahony, Brooks, Babb, Nunes.

Study supervision: Levin, Mariani, Mooney, Mahony, Nunes, Grabowski.

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: No other disclosures were reported.

Supplemental content at jamapsychiatry.com

REFERENCES

- 1.Barkley RA, Brown TE. Unrecognized attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in adults presenting with other psychiatric disorders. CNS Spectr. 2008;13(11):977–984. doi: 10.1017/s1092852900014036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lee SS, Humphreys KL, Flory K, Liu R, Glass K. Prospective association of childhood attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and substance use and abuse/dependence: a meta-analytic review. Clin Psychol Rev. 2011;31(3):328–341. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2011.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wilens TE, Martelon M, Joshi G, et al. Does ADHD predict substance-use disorders? a 10-year follow-up study of young adults with ADHD. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2011;50(6):543–553. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2011.01.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Biederman J, Wilens T, Mick E, Milberger S, Spencer TJ, Faraone SV. Psychoactive substance use disorders in adults with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD): effects of ADHD and psychiatric comorbidity. Am J Psychiatry. 1995;152(11):1652–1658. doi: 10.1176/ajp.152.11.1652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Knop J, Penick EC, Nickel EJ, et al. Childhood ADHD and conduct disorder as independent predictors of male alcohol dependence at age 40. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2009;70(2):169–177. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2009.70.169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kessler RC, Adler L, Barkley R, et al. The prevalence and correlates of adult ADHD in the United States: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(4):716–723. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.163.4.716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Simon V, Czobor P, Bálint S, Mészáros A, Bitter I. Prevalence and correlates of adult attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder: meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry. 2009;194(3):204–211. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.107.048827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Levin FR, Evans SM, Kleber HD. Prevalence of adult attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder among cocaine abusers seeking treatment. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1998;52(1):15–25. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(98)00049-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.van Emmerik-van Oortmerssen K, van de Glind G, van den Brink W, et al. Prevalence of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder in substance use disorder patients: a meta-analysis and meta-regression analysis. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2012;122(1–2):11–19. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.van de Glind G, van den Brink W, Koeter MW, et al. IASP Research Group. Validity of the Adult ADHD Self-Report Scale (ASRS) as a screener for adult ADHD in treatment seeking substance use disorder patients. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2013;132(3):587–596. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2013.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carroll KM, Rounsaville BJ. History and significance of childhood attention deficit disorder in treatment-seeking cocaine abusers. Compr Psychiatry. 1993;34(2):75–82. doi: 10.1016/0010-440x(93)90050-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Levin FR, Evans SM, Vosburg SK, Horton T, Brooks D, Ng J. Impact of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder and other psychopathology on treatment retention among cocaine abusers in a therapeutic community. Addict Behav. 2004;29(9):1875–1882. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2004.03.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Faraone SV, Glatt SJ. A comparison of the efficacy of medications for adult attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder using meta-analysis of effect sizes. J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;71(6):754–763. doi: 10.4088/JCP.08m04902pur. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Weisler RH, Biederman J, Spencer TJ, et al. Mixed amphetamine salts extended-release in the treatment of adult ADHD: a randomized, controlled trial. CNS Spectr. 2006;11(8):625–639. doi: 10.1017/s1092852900013687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mariani JJ, Pavlicova M, Bisaga A, Nunes EV, Brooks DJ, Levin FR. Extended-release mixed amphetamine salts and topiramate for cocaine dependence: a randomized controlled trial. Biol Psychiatry. 2012;72(11):950–956. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2012.05.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Herin DV, Rush CR, Grabowski J. Agonist-like pharmacotherapy for stimulant dependence: preclinical, human laboratory, and clinical studies. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2010;1187:76–100. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05145.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Grabowski J, Rhoades H, Stotts A, et al. Agonist-like or antagonist-like treatment for cocaine dependence with methadone for heroin dependence: two double-blind randomized clinical trials. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2004;29(5):969–981. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mooney ME, Herin DV, Schmitz JM, Moukaddam N, Green CE, Grabowski J. Effects of oral methamphetamine on cocaine use: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2009;101(1–2):34–41. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.10.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Castaneda R, Levy R, Hardy M, Trujillo M. Long-acting stimulants for the treatment of attention-deficit disorder in cocaine-dependent adults. Psychiatr Serv. 2000;51(2):169–171. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.51.2.169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.O'Leary G, Weiss RD. Pharmacotherapies for cocaine dependence. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2000;2(6):508–513. doi: 10.1007/s11920-000-0010-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wilens TE, Gignac M, Swezey A, Monuteaux MC, Biederman J. Characteristics of adolescents and young adults with ADHD who divert or misuse their prescribed medications. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2006;45(4):408–414. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000199027.68828.b3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Biederman J, Spencer TJ, Wilens TE, Weisler RH, Read SC, Tulloch SJ, SLI381.304 Study Group Long-term safety and effectiveness of mixed amphetamine salts extended release in adults with ADHD. CNS Spectr. 2005;10(suppl 20):16–25. doi: 10.1017/s1092852900002406. 12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Volkow ND, Fowler JS, Wang GJ. Imaging studies on the role of dopamine in cocaine reinforcement and addiction in humans. J Psychopharmacol. 1999;13(4):337–345. doi: 10.1177/026988119901300406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Levin FR, Mariani JJ. Co-occurring addictive disorder and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. In: Ries RK, Fiellin DA, Miller SC, Saitz R, editors. The ASAM Principles of Addiction Medicine. 5th ed Wolters Kluwer Health; Philadelphia, PA: 2014. pp. 1365–1384. [Google Scholar]

- 25.First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders, Patient Edition (SCID-I/P), Version 2.0. Biometrics Research, New York State Psychiatric Institute; New York: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Epstein JN, Johnson DE, Conners CK. Conners' Adult ADHD Diagnostic Interview for DSM-IV (CAADID). Multi-Health Systems; North Tonawanda, NY: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Spencer TJ, Adler LA, Meihua Qiao, et al. Validation of the Adult ADHD Investigator Symptom Rating Scale (AISRS) J Atten Disord. 2010;14(1):57–68. doi: 10.1177/1087054709347435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Conners C, Erhardt JN, Sparrow E. Conners' Adult ADHD Rating Scale (CAARS) Multi-Health Systems; North Tonawanda, NY: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Conners CK. Clinical use of rating scales in diagnosis and treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Pediatr Clin North Am. 1999;46(5):857–870. doi: 10.1016/s0031-3955(05)70159-0. vi. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Guy W. ECDEU Assessment Manual for Psychopharmacology. US Dept of Health, Education & Welfare; Rockville, MD: 1976. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Litten R, Allen J. Measuring Alcohol Consumption: Psychosocial and Biochemical Methods. Humana Press; Totowa, NJ: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Carroll KM, Rounsaville BJ, Gordon LT, et al. Psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy for ambulatory cocaine abusers. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1994;51(3):177–187. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1994.03950030013002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Levine J, Schooler NR. SAFTEE: a technique for the systematic assessment of side effects in clinical trials. Psychopharmacol Bull. 1986;22(2):343–381. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wilens TE, Haight BR, Horrigan JP, et al. Bupropion XL in adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a randomized, placebo-controlled study. Biol Psychiatry. 2005;57(7):793–801. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.01.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Spencer T, Biederman J, Wilens T, et al. Efficacy of a mixed amphetamine salts compound in adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2001;58(8):775–782. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.8.775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.SAS PROC GENMOD. SAS Institute; Cary, NC: 2000. computer program. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Weisler R, Young J, Mattingly G, Gao J, Squires L, Adler L, 304 Study Group Long-term safety and effectiveness of lisdexamfetamine dimesylate in adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. CNS Spectr. 2009;14(10):573–585. doi: 10.1017/s1092852900024056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Castells X, Casas M, Pérez-Mañá C, Roncero C, Vidal X, Capellà D. Efficacy of psychostimulant drugs for cocaine dependence. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;(2):CD007380. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007380.pub3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cunill R, Castells X, Tobias A, Capellà D. Pharmacological treatment of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder with co-morbid drug dependence. J Psychopharmacol. 2015;29(1):15–23. doi: 10.1177/0269881114544777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pérez-Mañá C, Castells X, Torrens M, Capellà D, Farre M. Efficacy of psychostimulant drugs for amphetamine abuse or dependence. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;9:CD009695. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009695.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Konstenius M, Jayaram-Lindström N, Guterstam J, Beck O, Philips B, Franck J. Methylphenidate for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and drug relapse in criminal offenders with substance dependence: a 24-week randomized placebo-controlled trial. Addiction. 2014;109(3):440–449. doi: 10.1111/add.12369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Heal DJ, Buckley NW, Gosden J, Slater N, France CP, Hackett D. A preclinical evaluation of the discriminative and reinforcing properties of lisdexamfetamine in comparison to D-amfetamine, methylphenidate and modafinil. Neuropharmacology. 2013;73:348–358. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2013.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hser YI, Saxon AJ, Huang D, et al. Treatment retention among patients randomized to buprenorphine/naloxone compared to methadone in a multi-site trial. Addiction. 2014;109(1):79–87. doi: 10.1111/add.12333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schottenfeld RS, Pakes JR, Oliveto A, Ziedonis D, Kosten TR. Buprenorphine vs methadone maintenance treatment for concurrent opioid dependence and cocaine abuse. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1997;54(8):713–720. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1997.01830200041006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mao AR, Babcock T, Brams M. ADHD in adults: current treatment trends with consideration of abuse potential of medications. J Psychiatr Pract. 2011;17(4):241–250. doi: 10.1097/01.pra.0000400261.45290.bd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Weisler RH, Childress AC. Treating attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in adults: focus on once-daily medications. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2011;13(6) doi: 10.4088/PCC.11r01168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Winhusen TM, Lewis DF, Riggs PD, et al. Subjective effects, misuse, and adverse effects of osmotic-release methylphenidate treatment in adolescent substance abusers with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2011;21(5):455–463. doi: 10.1089/cap.2011.0014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mariani JJ, Levin FR. Psychostimulant treatment of cocaine dependence. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2012;35(2):425–439. doi: 10.1016/j.psc.2012.03.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Comer SD, Mogali S, Saccone PA, et al. Effects of acute oral naltrexone on the subjective and physiological effects of oral D-amphetamine and smoked cocaine in cocaine abusers. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2013;38(12):2427–2438. doi: 10.1038/npp.2013.143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Evans SM, Levin FR, Brooks DJ, Garawi F. A pilot double-blind treatment trial of memantine for alcohol dependence. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2007;31(5):775–782. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2007.00360.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Levin FR, Mariani JJ, Brooks DJ, Pavlicova M, Cheng W, Nunes EV. Dronabinol for the treatment of cannabis dependence: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2011;116(1–3):142–150. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.12.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ameringer KJ, Leventhal AM. Associations between attention deficit hyperactivity disorder symptom domains and DSM-IV lifetime substance dependence. Am J Addict. 2013;22(1):23–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1521-0391.2013.00325.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kishi T, Matsuda Y, Iwata N, Correll CU. Antipsychotics for cocaine or psychostimulant dependence: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized, placebo-controlled trials. J Clin Psychiatry. 2013;74(12):e1169–e1180. doi: 10.4088/JCP.13r08525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Haile CN, Mahoney JJ, III, Newton TF, De La Garza R., II Pharmacotherapeutics directed at deficiencies associated with cocaine dependence: focus on dopamine, norepinephrine and glutamate. Pharmacol Ther. 2012;134(2):260–277. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2012.01.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]