Abstract

During wakefulness the brain creates meaningful relationships between disparate stimuli in ways that escape conscious awareness. Processes active during sleep can strengthen these relationships, leading to more adaptive use of those stimuli when encountered during subsequent wake. Performance on the weather prediction task (WPT), a well-studied measure of implicit probabilistic learning, has been shown to improve significantly following a night of sleep, with stronger initial learning predicting more nocturnal REM sleep. We investigated this relationship further, studying the effect on WPT performance of a daytime nap containing REM sleep. We also added an interference condition after the nap/wake period as an additional probe of memory strength. Our results show that a nap significantly boosts WPT performance, and that this improvement is correlated with the amount of REM sleep obtained during the nap. When interference training is introduced following the nap, however, this REM-sleep benefit vanishes. In contrast, following an equal period of wake, performance is both unchanged from training and unaffected by interference training. Thus, while the true probabilistic relationships between WPT stimuli are strengthened by sleep, these changes are selectively susceptible to the destructive effects of retroactive interference, at least in the short term.

Keywords: sleep, memory, learning, probabilistic learning, REM sleep, retroactive interference

1. INTRODUCTION

Within the adage that sleeping on a problem will bring clarity in the morning lies a kernel of awareness of the obscure calculus at work within the brain each night. Anecdotal evidence has long suggested a role for sleep in the synthesis of information and facilitating insight, ranging from Kekulé's discovery of benzene's ring structure to the penning of Coleridge's romantic poem, Kubla Khan. Research suggests a significant role for sleep in facilitating the connection between elements encountered during the day—extracting, as it were, the gist of experience (Payne, Schacter et al. 2009). Intriguingly, sleep also forms connections between seemingly disparate elements, even working out subtle quantitative relationships we didn't explicitly set out to solve. For example, in a probabilistic task, in which participants learn (implicitly) to associate unrelated images with weather condition (rain or sunshine), unconscious processes actively at work across a night of sleep improve task performance the following day (Djonlagic, Rosenfeld et al. 2009).

Different stages of sleep appear to impact the evolution of memory for a wide range of tasks, with each sleep stage affecting memory processing in characteristic ways (Walker and Stickgold 2010). For example, slow-wave sleep (SWS), which predominates early in the night, benefits declarative (explicit) memory processing (Plihal and Born 1997, Tucker, Hirota et al. 2006). In contrast, REM sleep appears in greater amounts later in the night and is implicated in the processing of non-declarative memory (Plihal and Born 1997, Stickgold, Whidbee et al. 2000), including memory for complex relations (Wagner, Gais et al. 2004, Stickgold 2005, Cai, Mednick et al. 2009, Djonlagic, Rosenfeld et al. 2009) and skills (Smith and Smith 2003). More generally, REM sleep is thought to facilitate the integration and abstraction of distinct memories into schema that in theory represent the rules by which categorical sets behave (Walker and Stickgold 2010).

We used a classic probabilistic category learning paradigm, the Weather Prediction Task (WPT; Knowlton et al., 1994), as a probe for the abstraction by sleep of implicitly learned probabilistic rules. Four cards with line drawings of simple objects serve as stimuli, and participants see one, two, or three of these cards at each trial, which they use to predict “sun” or “rain” weather outcomes. Unbeknownst to the participants, each card has a fixed probability of predicting each outcome, and the probabilities associated with multiple-card combinations are derived from the individual card probabilities. These associations of individual cue cards and outcomes must be learned over a large number of presentations, as no single trial gives sufficient information to fully reveal these relationships.

Functional brain imaging studies show that the medial temporal lobes are normally active early in the learning phase of the task, but become less active as the basal ganglia become increasingly active later in learning (Poldrack, Prabhakaran et al. 1999, Poldrack, Clark et al. 2001), suggesting that information translocation may be a critical step in the progressive learning of this task.

In an earlier study, a night of sleep (but not an equal period of daytime wake) led to an absolute improvement in task performance (Djonlagic, Rosenfeld et al. 2009). In addition, a positive correlation was found between immediate post-training performance and the amount of REM sleep participants obtained during the following night (Djonlagic, Rosenfeld et al. 2009), implicating REM sleep in this sleep-dependent improvement.

Following this line of investigation, we used a nap paradigm to compare immediate post-training performance with performance on the task four hours later. We gave participants 90 minutes to nap in order to make REM sleep likely (Mednick, Nakayama et al. 2002), and had wake and nap participants train and retest at the same time, eliminating possible confounds due to circadian phase and time of day. In addition, we investigated the impact of interference training on prior task learning and improvement.

2. METHODS

2.1 Participants

Fifty-one healthy university students (35 female) took part in the study in exchange for payment. Participants were between the ages of 18 and 26 (20.9 ± 2.3 (SD)) with no self-reported history of drug abuse (including alcohol and narcotics) or use of psychoactive drugs, sedatives, or hypnotics, and with no reported psychiatric, neurologic, or sleep disorders. Participants who reported consuming >600 mg/day of caffeine were excluded from the study. All participants were instructed to maintain their usual sleep schedule and documented their sleep habits for the three nights immediately before the study (three-night mean sleep duration, Wake groups: 7.6 ± 0.17hrs, Nap groups: 7.6 ± 0.31hrs, p=.99). The study was approved by the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center Institutional Review Board, and all participants provided written informed consent.

Seven participants were excluded from analysis who either (i) failed to correctly report the trial outcome clearly displayed on screen in more than 15% of training trials or (ii) showed strong evidence of spontaneously reversing the definition of the response keys during either training or testing reflected in long sequences of consistent errors.

2.2 The Weather Prediction Task

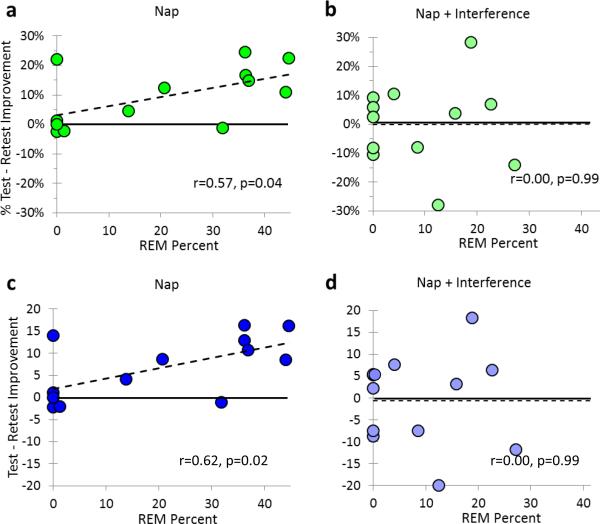

WPT stimuli were two sets of four cards with line drawings of objects in distinct categories (animal, vehicle, light, and small device). Each card had a fixed probability of occurring with Sun or Rain, with objects from the two sets in the same category having different probabilities (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Probability of Sun by card for each card set.

Initial task training

Task training consisted of 200 trials, on each of which participants were shown a card combination consisting of 1 to 3 of the 4 cards from Stimulus Set 1 (Fig. 1), along with a simple image of the sun or a rain cloud. A total of 14 possible card combinations were balanced across each of four 50-trial blocks. Prior to the start of training, participants were instructed to ‘attend to the cards displayed and to use the keys labeled “Sun” or “Rain” to enter a response matching the image of the weather condition shown immediately above the cards.’ Each trial screen asked, “Rain or Sun?” If no key was pressed within 2s of stimulus presentation, the reminder, “Answer now,” appeared. After 5s the program advanced to the next trial regardless of whether an answer had been entered. Faster responses did not advance the rate of stimulus presentation. The weather image presented on each training trial was determined probabilistically, based on the probabilities assigned to each of the displayed cards (Knowlton, Mangels et al. 1996), a fact not explicitly revealed to the participants.

Task testing

A 100-trial test immediately followed training, with stimuli again presented for 5s each, but without any weather symbol. Instead, participants were instructed to respond to each card combination with their ‘best guess of the weather condition predicted by the cards shown’. At each trial, participants saw the prompt, “Rain or Sun?” and responded by pressing the appropriate key. A response was scored as correct if the participant selected the weather choice that has the highest probability of occurring with the displayed card combination. Performance was scored as the percent of correct responses achieved during a test session. In all analyses, raw performance is adjusted for correct responses (adjusted score = [raw score - 0.5]/0.5; (Wagner, Gais et al. 2004, Stickgold 2005, Djonlagic, Rosenfeld et al. 2009).

Interference training

Interference training was identical to the initial task training except that it used Stimulus Set 2 (Fig. 1). The procedure for delivering the 200 training trials and 100-trial test was otherwise identical to that of the initial training and test.

2.3 Experimental Protocol

Immediately before initial testing, participants completed the Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS; Johns 1991). Before initial testing and following retest, participants completed the Stanford Sleepiness Scale (SSS; Hoddes, Zarcone et al. 1973), a standard measure of state subjective sleepiness, and provided additional subjective answers at both time points to written questions on their ability to concentrate and how refreshed they felt.

All participants trained on the WPT at 11AM and were tested on the task immediately following training (Fig. 2). Initial test results were calculated, and participants were assigned to one of four experimental groups (Nap, Wake, Nap + Interference, and Wake + Interference) pseudorandomly, based both on a rotating order and on initial test score, so as to minimize differences in mean group scores on initial testing. At 12PM, participants from both Nap groups began a 90-minute nap opportunity, monitored with EEG (C3, C4, F3, F4, O1, O2), chin EMG, and two EOG channels. Participants in both Wake groups watched videos during this interval. Sleep records were scored according to standardized scoring criteria (Rechtschaffen and Kales 1968). At 2PM, following the nap/wake interval, half of the participants underwent interference training. All participants were then retested on the original card set at 4PM. Performance was computed as the percentage of optimal weather predictions at training and retest. All analyses reflect post-exclusion groups of 13 Nap, 13 Wake, 12 Nap + Interference, and 13 Wake + Interference subjects.

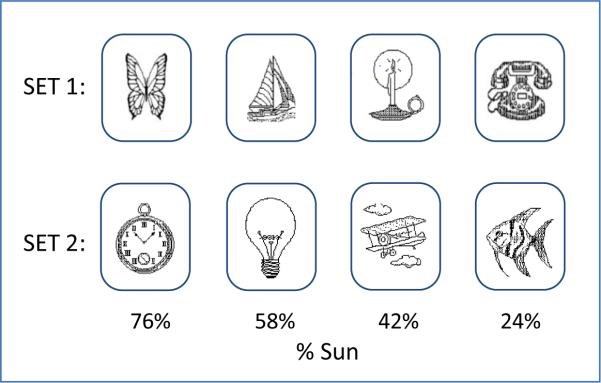

Figure 2.

Experimental protocol. Subjects underwent training and immediate testing on the WPT at 11AM and were retested at 4PM. Half of the participants had a 90min. nap opportunity, while half of the Wake participants and half of the Nap participants underwent interference training (without subsequent testing) at 2PM.

2.4 Statistical Analyses

Comparative group analyses of experimental variables were carried out using ANOVA, as well as unpaired Students t-tests (two-tailed). Correlations between changes in task performance and sleep stage variables were performed using Pearson's correlation analyses. All analyses were performed in SPSS.

3. RESULTS

3.1 Sleep quality and alertness

There were no significant group differences in “ability to concentrate,” how refreshed participants felt or SSS scores (Table 1), although differences were seen in ESS scores between the Nap and Wake groups. Nap groups slept an average of 72.1 ± 22.5 min. (SD) during the 90-minute sleep opportunity as measured by EEG recording.

Table 1.

Subjective alertness responses.

| Nap | Wake | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| ESS | 8.87± 0.72 | 6.24± 0.68 | .01 |

| SSS (Training) | 2.57± 0.20 | 2.56± 0.17 | .98 |

| SSS (Retest) | 2.18± 0.17 | 2.30± 0.28 | .72 |

| Concentrate (Training) | 74.7± 3.2 | 71.4± 2.7 | .44 |

| Concentrate (Retest) | 75.3± 4.1 | 68.9± 4.5 | .30 |

| Refreshed (Training) | 62.1± 4.38 | 60.1± 4.15 | .74 |

| Refreshed (Retest) | 73.3± 3.68 | 63.3± 4.69 | .10 |

Nap and Wake values represent the total responses for group [Nap + (Nap + Interference)] and [Wake + (Wake + Interference)], respectively. Values = mean ± sem. ESS=Epworth Sleepiness Scale; SSS=Stanford Sleepiness Scale.

In addition, no differences were seen between the Nap and Nap + interference groups in sleep parameters (Table 2) or in Epworth Sleepiness Scale scores (Table 1).

Table 2.

Sleep stage comparisons for the Nap and Nap + Interference groups.

| Nap | Nap + Interference | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wake | 26.8 ± 5.9 | 29.7 ± 6.6 | .74 |

| Stage 1 | 10.3 (14.7%) ± 2.2 | 7.3 (14.3%) ± 1.6 | .29 |

| Stage 2 | 31.9 (43.1%) ± 5.6 | 38.3 (53.4%) ± 5.6 | .42 |

| SWS | 17.0 (21.8%) ± 4.7 | 17.1 (23.1%) ± 3.1 | .98 |

| REM Sleep | 14.4 (20.5%) ± 4.0 | 7.8 (9.1%) ± 2.7 | .19 |

| Total Sleep Time | 73.5 ± 5.6 | 70.6 ± 7.4 | .76 |

Units are in minutes ± sem, with percentages of total sleep in parentheses. SWS = slow wave sleep (NREM stages 3 & 4).

3.2 WPT Performance

Performance on the initial, post-training test was virtually identical for the four groups (group averages = 80.0 - 82.3% correct; one-way ANOVA, p = 0.97; p > 0.62 (LSD corrected) for all group comparisons; Table 3).

Table 3.

Performance by group.

| Nap | Nap-I | Wake | Wake-I | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial test (Test 1) | 80.0 ± 2.9 | 81.6 ± 3.5 | 82.3 ± 3.2 | 81.1 ± 3.4 |

| Retest (Test 2) | 86.7 ± 1.4 | 81.0 ± 4.0 | 82.5 ± 3.0 | 79.3 ± 3.8 |

| Absolute improvement (Test 2 – Test 1) | 6.7 ± 2.0 | −0.6 ± 3.1 | 0.2 ± 1.4 | −1.7 ± 2.5 |

| Percent improvement (Test 2 – Test 1) | 9.5 ± 2.8 | −0.1 ± 4.2 | 0.6 ± 1.8 | −1.9 ± 3.4 |

Units are in average adjusted absolute score or percent improvement (of adjusted score); Values = mean ± sem. Nap-I – nap + interference; Wake-I – wake + interference.

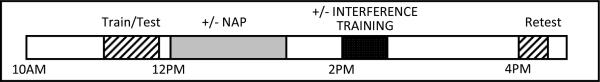

No change in performance was seen across 5hr of wake in either the Wake group (p = 0.89) or the Wake + Interference group (p = 0.50; Wake vs. Wake + Interference, t-test, p = .51; Fig. 3a).

Figure 3.

Change in adjusted score from initial testing to retest. Left: Absolute change – a The Nap group performed significantly better at Retest compared to Initial Test (p = 0.005 for absolute and % change); and b improved significantly more than all other groups (all p's < 0.05); Right: Percent change.

In contrast to the Wake and Wake + Interference groups, participants in the Nap group showed significant improvement at retest (p = 0.005; Fig. 3). Unexpectedly, this improvement was not seen when interference training followed the nap (p = 0.84). The improvement observed in the Nap group was significantly different from the other three groups (one-way ANOVA, absolute change: p = 0.049; percent change: p = 0.056; post-hoc comparisons, all p's < 0.05 for both percent and absolute change [LSD corrected]), and performance changes in the other three groups were essentially identical (all p's > 0.55 [LSD corrected]).

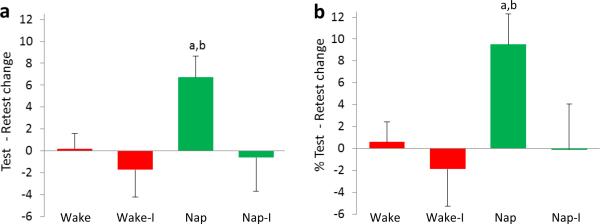

As a prior study demonstrated a correlation between WPT performance and subsequent REM sleep (Djonlagic, Rosenfeld et al. 2009), we sought to further explore the relationship between REM sleep and improvement by analyzing the correlation between post-sleep performance improvement and REM. In the Nap group, REM sleep was significantly correlated with improvement at retest (r = 0.57, p = 0.04; Fig. 4a.). Excluding subjects who obtained no REM sleep during the nap only improved the correlation (r = 0.71, p = 0.03), with REM sleep percent now explaining over half the variance in subsequent task improvement.

Figure 4.

Improvement vs. REM %. (a) % Improvement in the Nap group; (b) % Improvement in the Nap + Interference group; (c) Absolute improvement in the Nap group; (d) Absolute improvement in the Nap + Interference group.

Surprisingly, no similar correlation was seen in the Nap + Interference group (r = 0.004, p = 0.99; Fig. 4b.), even when subjects with no REM sleep were excluded (r = 0.004, p > 0.99). No other stages of sleep correlated significantly with post-nap improvement in either group (all p's > 0.33).

4. DISCUSSION

The neural mechanisms underlying a memory's post-encoding evolution through stabilization and enhancement remains obscure, although recent research has led to an increasingly nuanced sense of the timing and brain states involved in these processes (Rasch and Born 2013, Stickgold and Walker 2013). Memory stabilization, which reflects the classical definition of memory “consolidation”, can dramatically reduce both the general lability of memories and their specific susceptibility to interference. In some cases, stabilization occurs within 4hr after encoding, independent of sleep (Brashers-Krug, Shadmehr et al. 1996, Walker 2005), while in other cases, stabilization itself appears to require post-encoding sleep (Ellenbogen, Hulbert et al. 2006, Ellenbogen, Payne et al. 2006). In contrast, actual improvements in task performance are generally seen only following sleep (Laureys, Peigneux et al. 2002, Walker, Brakefield et al. 2002, Walker and Stickgold 2005).

Earlier work using the Weather Prediction Task (WPT) has shown that enhancement of performance develops across a night of sleep, but not over an equal period of daytime wake, and found that initial learning on the task correlated with subsequent overnight REM sleep (Djonlagic, Rosenfeld et al. 2009). But no probes of memory stabilization have been previously reported. Here, we asked whether a 90-min post-encoding nap opportunity would produce similar REM-related improvements in task performance, and whether such sleep would additionally would stabilize these memories, increasing their resistance to retroactive interference. To do so, we first trained participants on the WPT, and then, 2hrs later, after a 90-min nap opportunity or equivalent wake interval, retrained half of them on a version of the task using an alternate stimulus set, but with the same underlying probabilistic rules.

Our results indicate that a 90-min nap is sufficient to produce an absolute improvement in WPT performance, and that the magnitude of this improvement depends on the amount of REM sleep obtained, suggesting that processes active during REM sleep enhance WPT performance. In contrast, a similar period of time spent awake produced no improvement in performance, suggesting that these processes are, in fact, sleep-dependent.

The introduction of interference training following the nap period negated the performance benefit otherwise seen after a nap, but had no effect on wake performance, which remained unchanged from initial testing to retest. These results are surprising, and challenge assumptions both about memory consolidation and about the effects of interference. Ordinarily, stabilization would be assumed to precede, or at least to accompany, consolidation during sleep, as has previously been seen for declarative memories, which become resistant to interference post-sleep (Ellenbogen, Hulbert et al. 2006, Ellenbogen, Hulbert et al. 2009). Such sleep-dependent stabilization confers resistance to the destructive effects of interference. Yet here, the effects were reversed, with interference impairing performance after sleep, but not after wake.

Our findings bear some similarity to those of Deliens et al. (2013). Using a presumably SWS-dependent declarative memory task, they also found interference effects only after a nap, and not after an equivalent period or wake. In their case, interference effects were only seen after naps containing SWS. But more strikingly, unlike our findings, and those discussed above, in the absence of interference they found no improvement after a nap.

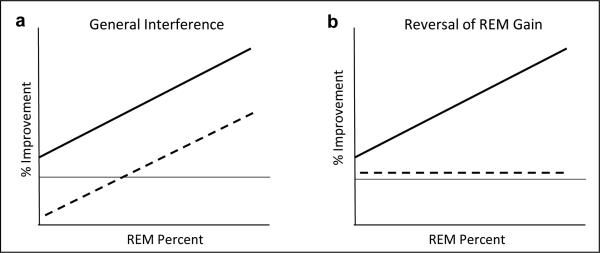

Our results suggest that interference training specifically reversed the sleep-dependent improvement, rather than causing a more general degradation of WPT memory. This interpretation is further supported by the disappearance of any REM sleep correlation with post-nap improvement in participants who received interference training. If the post-nap interference training resulted in a general 9-10% deterioration in performance compared to a nap alone (Fig 3), one would expect the graph in Figure 4B to show the same slope as in Figure 4A, simply shifted down so that the average change was near zero (Fig. 5a). Instead, it appears that it is specifically the REM-related improvement that is eliminated by interference training (Fig. 5b).

Figure 5.

Shift in correlation from Nap group (solid line) to Nap + Interference (dashed line). A: Assuming a general 9-10% deterioration in performance; B: Assuming a specific reversal of the improvement that occurred earlier during the Nap. Compare to Figure 4.

These findings suggest that the changes in WPT memory that occurred during sleep were distinct from the initial memory formed during training, perhaps enhancing associative links between newly formed memories (Stickgold and Walker 2013), located in a physically distinct brain region. Previous studies have found a shift from activation of medial temporal pathways to activation of those involving the basal ganglia in advanced training on the WPT (Poldrack, Prabhakaran et al. 1999, Poldrack, Temple et al. 2001). Reciprocal interference has been reported between declarative (explicit) and non-declarative (implicit) memory systems (Brown and Robertson 2007), with these two systems showing separate patterns of wake-sleep consolidation (Robertson, Pascual-Leone et al. 2004, Robertson 2012). In addition, a similar shift from the medial temporal lobe to the striatum on an auditory probabilistic task has been seen following sleep, correlating with SWS during the intervening sleep interval (Durrant, Cairney et al. 2013).

Whether the REM-sleep correlated WPT improvement that we report here involves a similar shift in regional dependence, and hence susceptibility to interference, remains unknown.

A second possible explanation is that the newly formed memory changes differed from those formed earlier in their cellular/synaptic structure, perhaps because of the relative recency of their formation at the time of interference training. Interference training this close to the time of memory modification might have been able to prevent the (re)consolidation of these sleep-dependent changes (Robertson 2012). While Diekelmann et al. (Diekelmann, Buchel et al. 2011) have argued that reactivation during SWS does not destabilize memories, whether this would be true for reactivation during REM is unknown. Similarly, Cordi et al. (Cordi, Diekelmann et al 2014) have demonstrated that attempting to reactivate declarative memories during REM sleep had no effect on the memories, although whether they were successfully reactivated and whether they would normally have been processed during REM sleep are both unknown.

4.1 Conclusion

Regardless of the mechanism responsible for these interference effects, the findings reported here suggest that, for probabilistic learning, sleep-dependent enhancements are REM dependent and remain sensitive to post-sleep interference during at least a brief, 30-min period of post-sleep wake.

Highlights.

A nap boosts performance on a recently learned probabilistic classification task.

Post-nap improvement is correlated with the amount of REM sleep obtained.

The REM-sleep benefit is eliminated by interference training following the nap.

Interference training has no effect after an equivalent period of wakefulness.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This study was supported in part by NIH grant MH48832. Study data were managed using REDCap electronic data capture tools hosted at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston. This work was conducted with support from Harvard Catalyst, The Harvard Clinical and Translational Science Center (National Center for Research Resources and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, NIH 8UL1TR000170 and financial contributions from Harvard University and its affiliated academic health care centers.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- Brashers-Krug T, Shadmehr R, Bizzi E. Consolidation in human motor memory. Nature. 1996;382(6588):252–255. doi: 10.1038/382252a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown RM, Robertson EM. Off-line processing: reciprocal interactions between declarative and procedural memories. J Neurosci. 2007;27(39):10468–10475. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2799-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai DJ, Mednick SA, Harrison EM, Kanady JC, Mednick SC. REM, not incubation, improves creativity by priming associative networks. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106(25):10130–10134. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0900271106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cordi M, Diekelmann S, Born J, Rasch B. No effect of odor-induced memory reactivation during REM sleep on declarative memory stability. Front Syst Neurosci. 2014;8:157. doi: 10.3389/fnsys.2014.00157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deliens G, Leproult R, Neu D, Peigneux P. Rapid eye movement and non-rapid eye movement sleep contributions in memory consolidation and resistance to retroactive interference for verbal material. Sleep. 2013;36(12):1875–1883. doi: 10.5665/sleep.3220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diekelmann S, Buchel C, Born J, Rasch B. Labile or stable: opposing consequences for memory when reactivated during waking and sleep. Nat Neurosci. 2011;14(3):381–386. doi: 10.1038/nn.2744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Djonlagic I, Rosenfeld A, Shohamy D, Myers C, Gluck M, Stickgold R. Sleep enhances category learning. Learn Mem. 2009;16(12):751–755. doi: 10.1101/lm.1634509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durrant SJ, Cairney SA, Lewis PA. Overnight consolidation aids the transfer of statistical knowledge from the medial temporal lobe to the striatum. Cereb Cortex. 2013;23(10):2467–2478. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhs244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellenbogen JM, Hulbert JC, Jiang Y, Stickgold R. The sleeping brain's influence on verbal memory: boosting resistance to interference. PLoS One. 2009;4(1):e4117. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellenbogen JM, Hulbert JC, Stickgold R, Dinges DF, Thompson-Schill SL. Interfering with theories of sleep and memory: sleep, declarative memory, and associative interference. Curr Biol. 2006;16(13):1290–1294. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.05.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellenbogen JM, Payne JD, Stickgold R. The role of sleep in declarative memory consolidation: passive, permissive, active or none? Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2006;16(6):716–722. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2006.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoddes E, Zarcone V, Smythe H, Phillips R, Dement WC. Quantification of sleepiness: a new approach. Psychophysiology. 1973;10(4):431–436. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.1973.tb00801.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johns MW. A new method for measuring daytime sleepiness: the Epworth sleepiness scale. Sleep. 1991;14(6):540–545. doi: 10.1093/sleep/14.6.540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knowlton BJ, Mangels JA, Squire LR. A neostriatal habit learning system in humans. Science. 1996;273(5280):1399–1402. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5280.1399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knowlton BJ, Squire LR, Gluck MA. Probabilistic classification learning in amnesia. Learn Mem. 1994;1(2):106–120. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laureys S, Peigneux P, Perrin F, Maquet P. Sleep and motor skill learning. Neuron. 2002;35(1):5–7. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00766-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mednick SC, Nakayama K, Cantero JL, Atienza M, Levin AA, Pathak N, Stickgold R. The restorative effect of naps on perceptual deterioration. Nat Neurosci. 2002;5(7):677–681. doi: 10.1038/nn864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Payne JD, Schacter DL, Propper RE, Huang LW, Wamsley EJ, Tucker MA, Walker MP, Stickgold R. The role of sleep in false memory formation. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2009;92(3):327–334. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2009.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plihal W, Born J. Effects of early and late nocturnal sleep on declarative and procedural memory. J Cogn Neurosci. 1997;9(4):534–547. doi: 10.1162/jocn.1997.9.4.534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poldrack RA, Clark J, Pare-Blagoev EJ, Shohamy D, Creso Moyano J, Myers C, Gluck MA. Interactive memory systems in the human brain. Nature. 2001;414(6863):546–550. doi: 10.1038/35107080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poldrack RA, Prabhakaran V, Seger CA, Gabrieli JD. Striatal activation during acquisition of a cognitive skill. Neuropsychology. 1999;13(4):564–574. doi: 10.1037//0894-4105.13.4.564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poldrack RA, Temple E, Protopapas A, Nagarajan S, Tallal P, Merzenich M, Gabrieli JD. Relations between the neural bases of dynamic auditory processing and phonological processing: evidence from fMRI. J Cogn Neurosci. 2001;13(5):687–697. doi: 10.1162/089892901750363235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasch B, Born J. About Sleep's Role in Memory. Physiological Reviews. 2013;93(2):681–766. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00032.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rechtschaffen A, Kales A. A manual of standardized terminology, techniques and scoring system for sleep stages of human subjects. Neurological Information Network; Bethesda, Md: 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Robertson EM. New insights in human memory interference and consolidation. Curr Biol. 2012;22(2):R66–71. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2011.11.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson EM, Pascual-Leone A, Press DZ. Awareness modifies the skill-learning benefits of sleep. Curr Biol. 2004;14(3):208–212. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.01.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith C, Smith D. Ingestion of ethanol just prior to sleep onset impairs memory for procedural but not declarative tasks. Sleep. 2003;26(2):185–191. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stickgold R. Sleep-dependent memory consolidation. Nature. 2005;437(7063):1272–1278. doi: 10.1038/nature04286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stickgold R, Walker MP. Sleep-dependent memory triage: evolving generalization through selective processing. Nat Neurosci. 2013;16(2):139–145. doi: 10.1038/nn.3303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stickgold R, Whidbee D, Schirmer B, Patel V, Hobson JA. Visual discrimination task improvement: A multi-step process occurring during sleep. J Cogn Neurosci. 2000;12(2):246–254. doi: 10.1162/089892900562075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tucker MA, Hirota Y, Wamsley EJ, Lau H, Chaklader A, Fishbein W. A daytime nap containing solely non-REM sleep enhances declarative but not procedural memory. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2006;86(2):241–247. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2006.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner U, Gais S, Haider H, Verleger R, Born J. Sleep inspires insight. Nature. 2004;427(6972):352–355. doi: 10.1038/nature02223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker MP. A refined model of sleep and the time course of memory formation. Behav Brain Sci. 2005;28(1):51–64. doi: 10.1017/s0140525x05000026. discussion 64-104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker MP, Brakefield T, Morgan A, Hobson JA, Stickgold R. Practice with sleep makes perfect: sleep-dependent motor skill learning. Neuron. 2002;35(1):205–211. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00746-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker MP, Stickgold R. It's practice, with sleep, that makes perfect: implications of sleep-dependent learning and plasticity for skill performance. Clin Sports Med. 2005;24(2):301–317. doi: 10.1016/j.csm.2004.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker MP, Stickgold R. Overnight alchemy: sleep-dependent memory evolution. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2010;11(3):218. doi: 10.1038/nrn2762-c1. author reply 218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]