Summary

Mimivirus was initially identified as a bacterium because its dense, 125nm-long fibers stained Gram-positive. These fibers probably play a role during the infection of some host cells. The normal hosts of Mimivirus are unknown, but in the laboratory Mimivirus is usually propagated in amoeba. The structure of R135, a major component of the fibrous outer layer of Mimivirus, has been determined to 2Å resolution. The protein's structure is similar to members of the glucose-methanol-cholin oxidoreductase family, which have an N-terminal FAD binding domain and a C-terminal substrate recognition domain. The closest homologue to R135 is an aryl alcohol oxidase that participates in lignin biodegradation of plant cell walls. Thus R135 might participate in the degradation of their normal hosts, including some lignin-containing algae.

Keywords: fibers, infection, Mimivirus, Mimivirus host, oxidoreductase, virus structure

Introduction

Acanthamoeba polyphaga Mimivirus, the prototypic member of the family of Mimiviridae, was isolated from a water tower in Bradford, UK. It initially was identified as a Gram-positive bacterium due to a highly glycosylated, dense layer of fibers (La Scola et al., 2003). A subsequent study recognized the viral nature of this particle, placing Mimivirus into the group of nucleocytoplasmic double-stranded DNA viruses (NCLDVs) (La Scola et al., 2003). Its genome of 1.2 Mbp (Raoult, 2004) encodes 979 open reading frames of which 42 are common genes in other NCLDVs. About 24% of the Mimivirus genes have homologs in bacteria, archea and eukaryotes. However, almost half of the Mimivirus genes encode proteins with no known homologs. Furthermore, no homologous sequences can be found for 39% of the proteins that can be isolated from the mature virions (Renesto et al., 2006).

Structural studies of Mimivirus show that the virus has an overall icosahedral shape, with a unique fivefold structure termed the stargate (Xiao et al., 2005; 2009) because it is probably where the genome exits the capsid when the virus infects a host (Zauberman et al., 2008). A dense layer of 125 nm-long fibers covers the whole virus except for the stargate (Kuznetsov et al., 2010; Xiao et al., 2009). Each fiber is capped by a small protein of unknown function(Kuznetsov et al., 2010). The fibers are resistant to protease treatment unless the virus is first treated with lysozyme(Xiao et al., 2009).

The role of the fibers in the life cycle of Mimivirus is not well understood, but because the fibers mimic the peptidoglycan layers found in Gram-positive bacteria, they may aid entry of the virus into the amoeba host (Kuznetsov et al., 2010; La Scola et al., 2003; Raoult, 2004; Xiao et al., 2009). Boyer et al. (Boyer et al., 2011) have shown that R135, L725 and L829 are components of the fibers. None of these proteins are essential to maintain infectivity under laboratory conditions, but their deletion during serial passage leads to a loss of fibers on the particles (Boyer et al., 2011). This fiberless variant, M4, of Mimivirus does not allow replication of the Sputnik virophage. Furthermore, R135 is found in association with Sputnik on isolating it from amoeba (La Scola et al., 2008). Thus R135 is the protein that Sputnik uses to attach to Mimivirus for co-infection. R135 and L829 have been identified as major antigens of Mimivirus (Raoult et al., 2007). However, the M4 fiberless variant of Mimivirus showed no reactivity with sera from human patients (Boyer et al., 2011), confirming that these proteins are missing in M4.

R135 has homology to members of the glucose-methanol-cholin (GMC) oxidoreductases, which utilize FAD to carry out a wide variety of oxidation/reduction reactions. These proteins were found to have common structural features, such as a conserved FAD-binding domain and a variable substrate binding domain, as is also the case for other enzymes that depend on a bound nucleotide (Rossmann et al., 1974). R135 is a part of a gene cluster in the Mimivirus genome involved in glycosylation of viral surface proteins (Piacente et al., 2012), but the precise function of R135 remains unknown for now. Here we describe the structure of R135, the first Mimivirus protein structure to be determined that is related to capsid assembly and host infection.

Results and Discussion

Structure of R135

The R135 protein has a molecular weight of 75kDa and consists of 702 amino acids. The protein was successfully expressed in its Apo form in E. coli and ran as an apparent monomer on a size exclusion column but failed to crystalize. Secondary predictions showed that the first 50 amino acids were likely to be disordered. Therefore these residues were removed by generating a deletion construct, R135_50.

The truncated protein crystallized in three different space groups, P1, P21, and P212121. The Matthews coefficient suggested that the number of monomers in the asymmetric unit of these crystal forms were about 2, 14 and 10, respectively. The limit of resolution of these crystals was 2.0, 3.3 and 2.9Å. The presence of only two molecules in the P1 space group made this crystal form the best candidate for molecular replacement. A rotation function showed that there was a major non-crystallographic 2-fold axis.

The P1 crystal structure of R135_50 was initially solved by molecular replacement using seven homologous GMC structures found in the PDB. These structures had between 20% and 30% sequence identity and had about 100 fewer residues in their sequences than R135_50. These trials also included using an ensemble of these seven proteins trimmed of some structural variable regions as implemented in the PHASER program (McCoy et al., 2007). The best of these solutions was then used to compute phases for an initial solution. This model and its electron density were refined using the Rosetta program in which the energy of the model as well as the current density distribution were considered (Dimaio et al., 2011; Terwilliger et al., 2012). The resultant model was further improved by cycles of rebuilding and crystallographic refinement using the phenix.refine program (Afonine et al., 2012). Refinement included restraints to impose the non-crystallographic symmetry (NCS), although rebuilding was done independently for each monomer. The first three residues were found to be disordered in both monomers. The final Rwork value was 16.3% and Rfree was 20.4%. The root-mean-square displacement (r.m.s.d.) between equivalent Cα atoms in the two monomers was 0.2Å on superimposing the two monomers (Table 1). The structure showed extensive interactions between the two independent monomers in the crystallographic asymmetric unit. Furthermore, the monomers are related by a 2-fold NCS axis and analytical centrifugation, confirmed the existence of dimers in solution.

Table 1. Crystallographic Statistics.

| R135 | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Data collection | |||

|

| |||

| X-ray wavelength (Å) | 1.0332 | 1.0332 | 1.0332 |

|

| |||

| Space group | P1 | P212121 | P21 |

|

| |||

| Cell dimensions | |||

|

| |||

| a,b,c (in Å) | 64.76, 77.50, 94.34 | 101.32, 240.50, 295.65 | 169.97, 154.94, 197.39 |

|

| |||

| α,β,γ (in degrees) | 111.221, 109.636, 94.556 | 90, 90, 90 | 90, 103.57, 90 |

|

| |||

| Resolution (Å)2 | 2 (2.00 – 2.07) | 2.91 (2.99 - 2.91) | 3.34 (3.46 - 3.34) |

| Rmerge2 | 0.209 (0.992) | 0.182 (0.674) | 0.179 (0.392) |

|

| |||

| I/ΔI2 | 6.30 (1.60) | 8.4 (2.3) | 9.20 (4.40) |

|

| |||

| Completeness (%)2 | 99.2 (99.3) | 96.2 (84.3) | 99.1 (99.4) |

|

| |||

| Overall Redundancy | 3.4 | 4.3 | 3.1 |

|

| |||

| Refinement | |||

|

| |||

| No. of reflections | 105150 | 158141 | 141759 |

| Rwork/Rfree | 0.1630/0.2037 | 0.1654/0.2141 | 0.1518/0.2081 |

|

| |||

| Average B-factor | 25.07 | 26.12 | 21.7 |

|

| |||

| R.m.s deviations | |||

|

| |||

| Bond length (Å) | 0.008 | 0.009 | 0.012 |

|

| |||

| Bond angles (deg.) | 1.087 | 1.265 | 1.567 |

|

| |||

| Ramachandran plot (%) | |||

|

| |||

| Favored | 96.3 | 96.6 | 96.1 |

|

| |||

| Allowed | 3.7 | 3.4 | 3.9 |

|

| |||

| Outliers | 0 | 0 | 0 |

The program Phaser was utilized to determine the two other crystal forms, using the R135_50 dimer structure as a search model. The P21 and P212121 crystal forms were found to contain 6 and 4 dimers per crystallographic asymmetric unit respectively, roughly consistent with the Matthews coefficient.

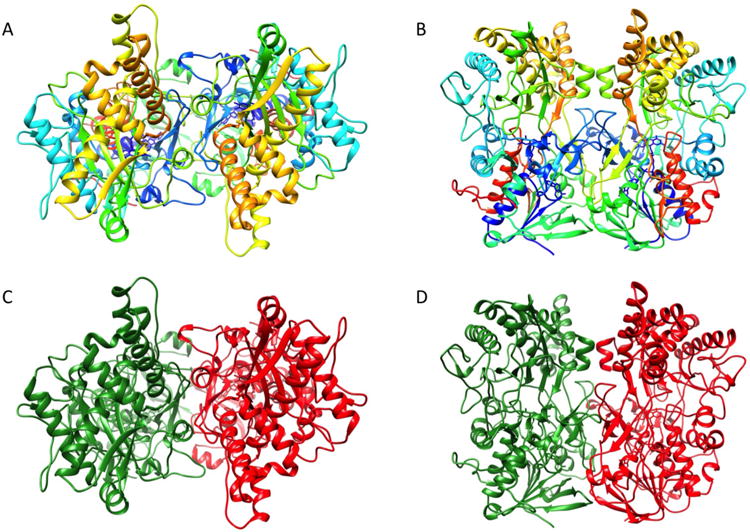

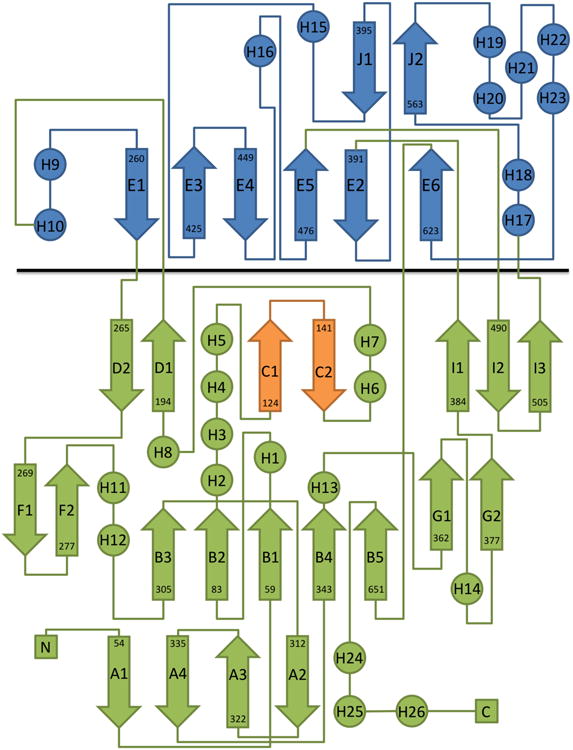

The overall fold of R135 is similar to other members of the GMC oxidoreductase family(Cavener, 1992) (Figure 1). The protein consists of a FAD-binding domain and a substrate recognition domain. These domains have the same conserved relative relationship to each other in all the known structures of these enzymes. The “N-terminal” part is composed of a five-stranded parallel β-sheet with the same sequence of β-strands typical of a nucleotide binding fold (Rossmann et al., 1974), with α-helices packed against each side of the β-sheet (Figure 2). The positions of these helices are consistent with being “right-handed cross-over” structures (Richardson, 1976). The “C-terminal” domain is the potential substrate-binding domain and consists of two antiparallel β-sheets and four α-helices. Although the FAD binding and substrate binding domains are primarily in the N-and C-terminal part of the sequence, respectively, parts of the structure of each domain are insertions in the other domain, as is the case in all known members of this family. A structure based comparison of R135 with other members of the GMC oxidoreductase family using the SALAMI server (http://flensburg.zbh.uni-hamburg.de/∼wurst/salami/) shows that the closest homologues in the PDB are a fungal aryl alcohol oxidase (FAAO) involved in lignin biodegradation (PDB: 3FIM) (Fernández et al., 2009) and a formate oxidase (PDB: 3Q9T) (Doubayashi et al., 2011). There are overall r.m.s.d's of about 3Å between equivalenced Cα atoms for 75.6% and 78% of the residues in the R135_50 and FAAO/formate oxidase structures and a sequence identity of 18% and 22%, respectively. The structural and sequence similarity is greater for the N-terminal FAD binding domain than for the C-terminal domain (Table 2). As most plant cells, such as in seaweed or some algae, contain lignin in their cell walls, it seems probable that Mimivirus might have an alternative host that has a lignin-containing cell wall which needs to be degraded for successful entry. Thus, Mimivirus might be able to infect water plants or lignin-containing algae although finding such a host among hundreds of possibilities might be difficult. Amoeba, however, does not have a cell wall, consistent with the observation that bald Mimivirus, which does not contain R135, infects amoeba as does the wild-type fibered virus. The possibility that Mimivirus might infect alternative hosts was also implied recently by the discovery that Mimiviruses were found to be abundant in oysters (Andrade et al., 2014).

Figure 1. Structure of R135.

(A) Top view and side view of a R135 dimer rainbow colored from blue at the N-terminus to red at the C-terminus.

(B) Top view and side view of a R135 dimer. Each monomer is colored in red and green respectively.

Figure 2. Topology Diagram of R135.

The FAD binding domain and the substrate recognition domain are colored in green and blue, respectively, and are separated by a black line. The FAD binding loop involved in dimer formation is shown in orange.

Table 2. r.m.s.d. Between GMC.

| Choline Oxidase (3NNE) | Pyridoxine 4-Oxidase (4HA6) | Aryl-Alcohol Oxidase (3FIM) | Probable Choline dehydrogenase (UniprotKB: X5ZQU6) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sequence identity (%) | 20 | 19 | 22 | 30 |

| Aligned amino acids | 486 | 478 | 489 | 538 |

| Overall r.m.s.d (in Å) | 2.2 | 2.1 | 2.3 | - |

| N-terminal domain r.m.s.d (in Å) | 1.8 | 1.7 | 1.8 | - |

| C-terminal domain r.m.s.d (in Å) | 2.8 | 2.8 | 3.0 | - |

The R135 Dimer

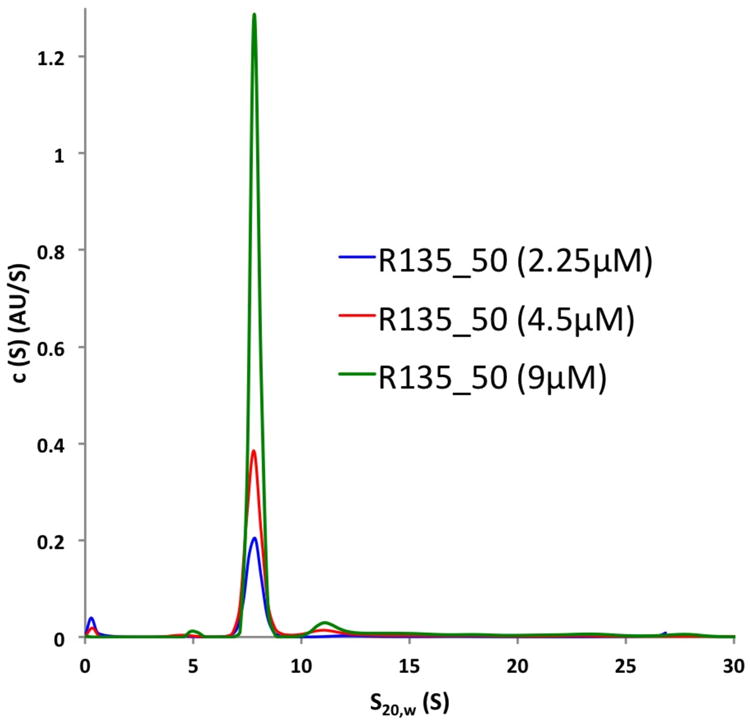

Analysis of the dimer interface shows that the buried surface area between the monomers is 2,893 Å2, corresponding to a solvent free energy of 18 kcal/mol (Krissinel and Henrick, 2007). The oligomeric state of R135_50 was also analyzed by analytical ultracentrifugation which showed that more than 90% of the protein was found to be dimeric, independent of its concentration (Figure 3). The remaining 10% were higher molecular weight assemblies. A substantial amount of the dimer-forming surface is formed by the loop between β-strands C1 and C2 (Figure 2). This loop is longer than 4 amino acids (aa) for those GMC oxidoreductases that form a dimer, consistent with the present case in which there are 12 aa that participate in forming a dimer. This loop has occasionally been referred to as the “FAD loop” (Kiess et al., 1998). Other members of the GMC oxidoreductase family are also oligomeric, particularly those that are active in an extracellular environment

Figure 3. Oligomer Formation of R135 in Solution Analyzed by Sedimentation Velocity Centrifugation.

The majority of R135 forms a dimer with a sedimentation coefficient of 7.8S in solution, independent of the protein concentration.

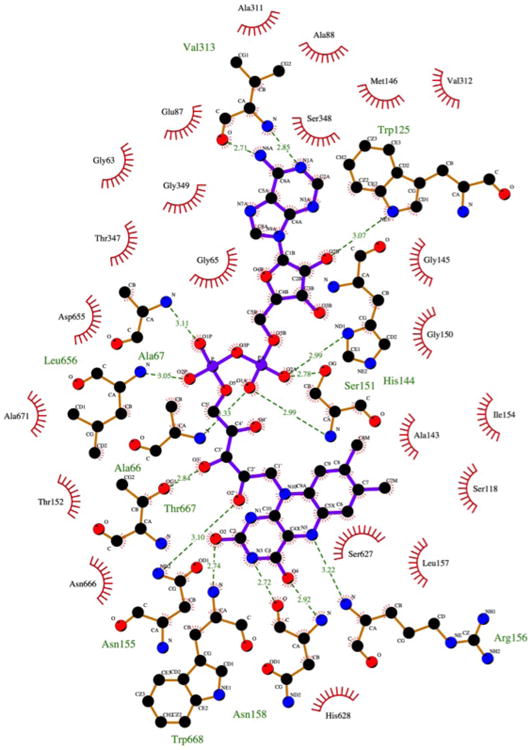

FAD Binding Site

The nucleotide-binding fold binds the cofactor at the carboxy end of the β-strands of the sheet, as is the case in FAD oxidoreductases and all other nucleotide binding structures that utilize a similar fold. The FAD is tightly bound and stabilized by a network of direct or water mediated hydrogen bonds (Figure 4). Residues in proximity to the cofactor that are also sequentially and spatially conserved in GMC oxidoreductases include Ala67, Ser151, Asn155 as well as glycines in position 63, 65, 145, 149 and 150 in R135. A structural superposition of R135 with glucose oxidase (GOX) (Wohlfahrt et al., 1999), cholesterol oxidase (CHOX) (Li et al., 1993; Pollegioni et al., 1999) or aryl-alcohol oxidase (AAO) (Fernández et al., 2009) shows that His628 corresponds to the active site histidine conserved in all these proteins.

Figure 4. FAD Cofactor and its Protein Environment.

Shown are the residues involved in hydrogen bonds (depicted by dashed lines) and hydrophobic interactions with the flavin ligand. The figure was generated using the program LIGPLOT+(Laskowski and Swindells, 2011).

The isoalloxine ring of the FAD molecule is slightly bent along the N5-N10 axis (Figure 5). Although this “butterfly” conformation (Mathews, 1991; Mattevi, 2006) is energetically unfavorable in comparison to a planar structure, this structure has been observed in several GMC oxidoreductase family members (Fernández et al., 2009; Li et al., 1993) and might assist the redox reaction by activating the cofactor.

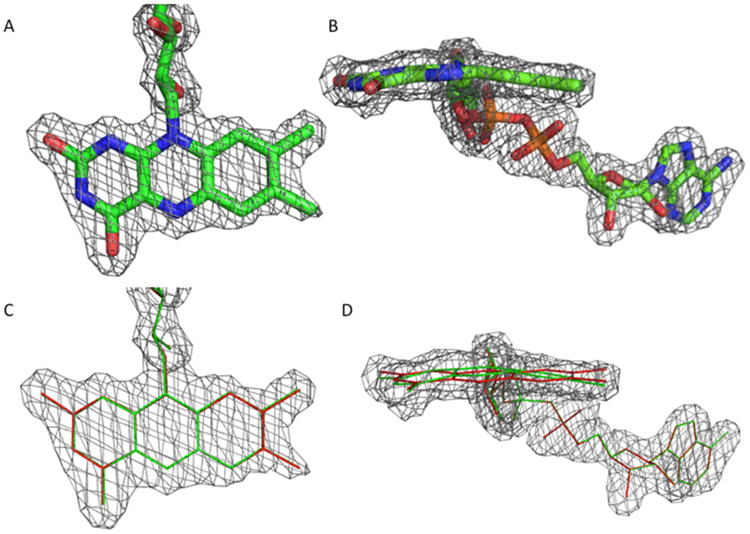

Figure 5. Electron Density Surrounding the FAD Cofactor.

(A) Model of the FAD cofactor shown from the top and side. The 2Fo-Fc electron density map drawn at a σ level of 1.0 is shown as a mesh.

(B) Overlays of a planar (red) and the observed butterfly (green) conformation shown from the top and side. The electron density map is displayed in the same way as in (A).

Substrate of R135

A comparison between the active centers of CHOX, GOX, AAO and R135 show some similarities. For example, CHOX has a catalytic tetrad, consisting of a His, Glu, and Asn, as well as a water molecule. The histidine and asparagine correspond to His628 and Asn666 in R135 respectively, but Glu361 has been substituted by Met452 in R135 (Table 3). Thus, no substrate specificity can be readily deduced from structural comparisons given the available structures.

Table 3. Comparison of the Amino Acids in the Active Site.

| Glucose Oxidase (1GPE) | Choline Oxidase (3COX) | Aryl-Alcohol Oxidase (3FIM) | R135 |

|---|---|---|---|

| His520 | His447 | His502 | His628 |

| His563 | Asn485 | His546 | Asn666 |

| Phe418 | Glu361 | Ile391 | Met452 |

| Glu416 | Phe359 | Glu389 | Gln450 |

| Gly112 | Gly120 | Tyr92 | Arg156 |

| Trp519 | Tyr446 | Phe501 | Ser627 |

Conserved residues are in bold

Glucose, viosamine (4-amino-4,6-dideoxy-d-glucose), rhamnose and N-acetylglucosamine are the four major sugars found on Mimivirus proteins (Piacente et al., 2012). All but glucose were significantly reduced in viral preparations that were depleted of the surface fibers. Therefore, R135_50 was tested for its enzymatic activity towards glucose, rhamnose and N-acetylglucosamine using two separate assays. In addition, benzyl alcohol, methanol, ethanol, PEG 100, cholesterol and choline were assayed. These assays were unable to show any reactivity of R135_50 towards any of these potential substrates.

Having failed to find a likely substrate for R135 in this way, we started to consider the biological function of the GMC enzymes. That is when we realized aryl-alcohol oxidase has lignin degrading activity. We, therefore, turned our attention to assaying for such activity. Assaying for lignin degrading enzymes requires the use of substrates that have bonds the same as are frequently found in lignin.

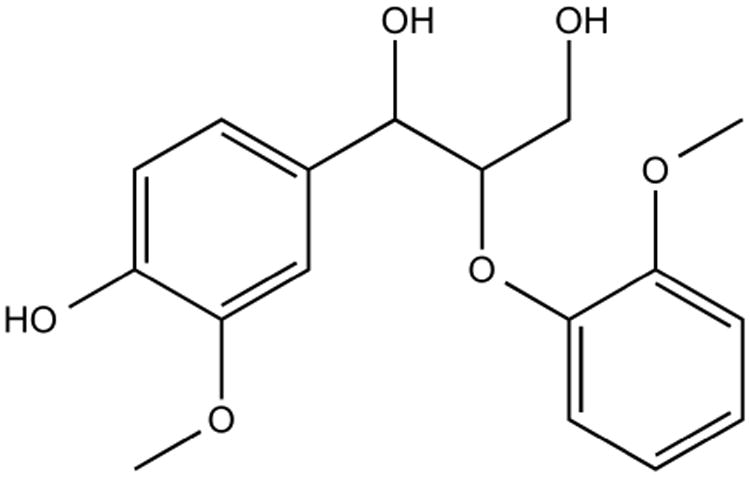

Guaiacylglycerol-beta-guaiacyl ether is a compound (Figure 6) frequently used for this purpose as it has a cleavable bond found in many different lignin structures. In using this compound for the assay and using mass spectroscopy to find the cleaved products, we determined that neither R135 on its own nor the complete virus were able to degrade guaiacylglycerol-beta-guaiacyl ether. Although guaiacylglycerol-beta-guaiacyl ether is one of the most common lignin model substrates, this does not eliminate the possibility of R135 degrading lignin or a lignin-like compound. Furthermore, as Mimivirus quickly mutated under laboratory conditions to its bald form (M4) (Boyer et al., 2011) and in this process lost R135 as well as other fiber associated proteins, it is likely that R135 gave the virus a competitive advantage in its natural environment. This advantage was likely associated with a broader host range that includes organisms with different lignin or lignin-like compounds in their cell walls.

Figure 6. Lignin Model Dimer.

Chemical structure of guaiacylglycerol-beta-guaiacyl ether, the compound used in all lignin degradation assays.

Glycosylation of R135

R135 used in this study is from a recombinant bacterial source and is, therefore, not glycosylated. However, this protein is highly glycosylated in mature particles of Mimivirus, a property that could influence the high immunogenicity of the virus (Boyer et al., 2011; Raoult et al., 2007). Little is known about the glycosylation machinery encoded by Mimivirus and its potential glycosylation sites. PBCV-1, another member of the NCLDVs, encodes its own glycosyltransferases that require specific recognition sequences (sequons), different to those used in eukaryotes (De Castro et al., 2013; Nandhagopal et al., 2002; Que et al., 1994). Assuming that the sequons found in PBCV-1 ((A/G)NTXT and ANIPG) are also valid for Mimivirus, there is one potential N-glycosylation site at Asn442, which is located on an exposed loop of the protein. Prediction of O-glycosylation sites using the DictOGlyc server, which has been trained on proteins of Dictyostelium discoideum (Gupta et al., 1999), shows that there are also potential O-glycosylation sites on R135 at Thr41 and Thr517. The former is not part of the present structure and the latter is located on an outside loop.

Location of R135 on Mimivirus

As R135 is highly antigenic and is responsible for attachment of Sputnik to Mamavirus/Mimivirus, it should be near the outside of the virus (Boyer et al., 2011; La Scola et al., 2008). However, these observations indicate only that R135 is located on the outside of the capsid shell, not whether it is associated only with fibers or is also a part of the integument layer outside of the viral shell (Kuznetsov et al., 2010; 2013). In order to identify the primary location of R135, the protein was incubated with Mimivirus and the bald variant of Mimivirus (M4). Subsequently the incubated virus was pelleted and the unbound protein present in the supernatant was visualized on a SDS-PAGE gel. The results showed that R135_50 binds to both, the bald as well as the fibered virus. The binding seems to be stronger with the fibered particles, which is in good agreement with the previously reported association of Sputnik and the fibers of Mimivirus in which R135 acts as a catalyst (Boyer et al., 2011). The binding of R135 to M4 suggests an affinity for the capsid shell or an interaction with some remaining small fibers.

Most bacterial viruses (bacteriophages) are equipped with one or more enzymes that help the virus to digest a part of the bacterial cell wall. For instance, phage T4 has three lysozyme molecules surrounding its tail that function to digest the peptidoglycan cell wall in the periplasmic space of Gram-negative bacteria (Arisaka et al., 2003; Kanamaru et al., 2002; Kao and McClain, 1980a; 1980b). Also, the terminal knob of phage phi29 is a peptidoglycan degrading enzyme (Xiang et al., 2008) and phiKZ is equipped with a lytic transglycosylase (Fokine et al., 2008; Miroshnikov et al., 2006). Furthermore, phage PT-6 has an alginate degrading enzyme that is responsible for degrading the capsule of its host (Glonti et al., 2010) and phage 370.1 has several hyaluronidase genes for the same purpose(Yan et al., 2014). In contrast, most viruses that infect eukaryotic cells enter by endocytosis and fusion with the plasma membrane. Mimivirus infects protists that often protect themselves with hard to penetrate cell walls. A similar situation is encountered for PBCV-1, which infects chlorella. This virus probably contains an enzyme in its unique vertex spike which is used to digest the cell wall of its host (Zhang et al., 2011). Thus, Mimivirus might achieve entry into a yet to be identified host by lignin digestion. However, thus far the original isolate of Mimivirus has been cultured only on amoeba where the long surface fibers encourage phagocytosis.

Experimental Procedures

Protein Production and Purification

R135_50, a variant lacking the first 50 amino acids, was amplified from Mimivirus DNA by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) using R135_50 fwd (GGC CAT ATG ACT AAA GAT AAT CTT ACA GGC GAC ATA G) and R135rev (CCC CGT CGA CTC AAT TAA CAT TGA GAA TTG GAA CAT CAT TAA CT). The PCR product was cloned into pET28a using NdeI and SalI. The protein was expressed in E. coli BL21(DE3) (Novagen) and purified by Ni-NTA affinity chromatography. The protein was further purified using ion exchange chromatography (HiTrap Q HP,GE Healthcare) and a final polishing step on a Size Exclusion column (Superdex 200 pg 16/60,GE Healthcare).

Crystallization and Structure Determination

R135_50 at a concentration of 10mg/ml was used to screen for crystallization conditions using Hampton (Hampton Research) and Emerald (Emerald Biosystems) crystallization screens. Drops were set up using a Honeybee crystallization robot (Digilab Inc.) utilizing sitting drops. The drops consisted of 0.5μl protein mixed with 0.5μl crystallization buffer. A few initial hits were obtained in conditions containing PEG 8,000. After optimization, needle-like crystals in three different space groups were obtained. The final crystallization conditions were 10% (w/v) PEG 8,000 and 100mM ammonium nitrate.

Crystals were harvested and flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen after soaking in a cryo protecting solution consisting of mother liquor and 50% (v/v) ethylene glycol. Multiple datasets were collected at the Advanced Photon Source, beamline 23-ID-B and 23-ID-D, GM/CA.

Images were processed using HKL2000 (Otwinowski and Minor, 1997) and XDS (Kabsch, 2010). The structure in space group P1 was solved using a combination of molecular replacement and structure modeling as implemented in phenix.mr_rosetta (Terwilliger et al., 2012). After model building and refinement the final structure was used to solve the two other crystal forms with 12 (for P21) and 8 (for P212121) monomers per asymmetric unit respectively using Phaser (McCoy et al., 2007). Refinement was carried out using phenix.refine (Afonine et al., 2005) from the PHENIX software package (Adams et al., 2010). NCS was enforced during refinement. Data collection and refinement statistics are summarized in Table 1.

Binding Assay

To analyze binding of R135_50 to Mimivirus a coprecipation assay was used. The protein was incubated with either Mimivirus (M1) or the bald variant of Mimivirus (M4) for 3h at room temperature. The virus and bound protein were subsequently pelleted by centrifugation at 10,000×g for 5min. The supernatant with the unbound protein, as well as a control of just R135_50 without virus was analyzed on a 12% SDS-PAGE gel and stained using Coomassie R250 (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA).

Substrate Tests

Two assays were utilized to determine substrate specificity. First, dichlorophenolindophenol (DCPIP) was used as an electron acceptor for which the reduction of DCPIP can be followed by a decrease in absorbance at 600nm. R135_50 at a final concentration of 0.1mg/mL was mixed with substrate plus 100μM DCPIP, and the change of absorption at 600nm was monitored over time.

The second assay was based on the transfer of electrons from a substrate to FAD during a reaction leading to a change of the spectral properties of the cofactor between 300 and 600nm. This has been successfully used to study the reaction kinetics of pyranose dehydrogenase (Tan et al., 2013). High substrate concentrations were incubated with R135_50 and spectra of the protein were taken at different time points.

Sample Preparation for Lignin Assay

To test for activity in the context of the whole virus, Mimivirus and the bald variant of Mimivirus (M4) were incubated with 1mM guaiacylglycerol-beta-guaiacyl ether in PBS at 37°C for 48h. Furthermore, 1mg/mL of R135_50 on its own was incubated with 1mM guaiacylglycerol-beta-guaiacyl ether in PBS at 37°C for 24h. R135_50 without substrate was used as a negative control.

Samples were desalted using Waters Oasis HLB 3 cc Vac Cartridges prior to HPLC-MS analysis. The cartridges were equilibrated with 10 mL of methanol followed by 10 mL of water. 2mL of sample were loaded and washed with 10 mL of water before being eluted with 2 mL of methanol. 25 μL of the eluents were injected for HPLC-MS analysis.

High Performance Liquid Chromatography/Mass Spectrometry

HPLC-MS analysis was performed using a Surveyor Plus HPLC system with a quaternary pump, an auto sampler, and a photodiode array (PDA) detector. The HPLC was coupled to a Thermo Scientific linear quadrupole ion trap (LQIT) mass spectrometer equipped with an electrospray ionization (ESI) source. Separation was performed using a Zorbax SB-C18 column. A non-linear gradient of water (A) and acetonitrile (B) was used as follows: 0.00 minutes, 95% A and 5% B; 10.00 minutes, 95% A and 5% B; 30.00 minutes, 40% A and 60% B; 35.00 minutes, 5% A and 95% B; 38.00 minutes, 5% A and 95% B; 38.50 minutes, 95% A and 5% B, 45.00 minutes, 95% A and 5% B. The mobile phase flow rate was kept at 500 μL/min throughout the gradient. HPLC eluents were mixed via a T-connector with 1% sodium hydroxide solution at a flow rate of 0.1 μL/min to facilitate deprotonation of the analytes. ESI source conditions were set as: 3.5 kV spray voltage; 50 (arbitrary unit) sheath gas (N2) flow and 20 (arbitrary unit) auxiliary gas (N2) flow. Ion detection was performed under negative ion mode. The PDA detector was set at a wavelength of 254 nm.

Highlights.

Mimivirus fibers play an important role during infection

First structure of a major component of the Mimivirus fiber

Member of the GMC oxidoreductase family

R135 is probably involved in the infection of alternative hosts

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Andrei Fokine, Pavel Plevka, Vidya Mangala Prasad Moh Lan Yap and Erica Zbornik for helpful discussions. We would like to thank Sheryl Kelly for help in submission of the manuscript. The authors acknowledge the use of the facilities of the Bindley Bioscience Center, a core facility of the NIH-funded Indiana Clinical & Translational Science Institute, as well as help from Lake N. Paul with analysis of the analytical ultracentrifugation data. Furthermore, we thank the staff at the beamline 23 GM/CA-CAT of Advanced Photon Source, Argonne National Laboratory for help with the data collection and the CCP4/APS School in Macromolecular Crystallography held in June 2012 for helpful discussion on various crystallographic topics. Use of the Advanced Photon Source was supported by the U.S. Department of Energy, Basic Energy Sciences, Office of Science, under contract No. DE-AC02-06CH11357. This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (AI011219 to MGR). The authors also gratefully acknowledge partial financial support by the Center for Direct Catalytic Conversion of Biomass to Biofuels (C3Bio), an Energy Frontier Research Center funded by the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences under Award Number DE-SC0000997 (H.Z., H.I.K.).

Footnotes

Accession Numbers: Atomic coordinates of R135 in space groups P1, P21 and P212121 were deposited with the Protein Data Bank under accession codes 4Z24, 4Z25 and 4Z26, respectively.

Author Contributions: T.K., D.A.H., H.Z. and J.P.M. performed experiments. T.K., H.Z., J.P.M, H.I.K and M.G.R. analyzed the data. T.K., H.I.K. and M.G.R. wrote the manuscript.

Conflict Of Interest: The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Adams PD, Afonine PV, Bunkóczi G, Chen VB, Davis IW, Echols N, Headd JJ, Hung LW, Kapral GJ, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, et al. PHENIX: a comprehensive Python-based system for macromolecular structure solution. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2010;66:213–221. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909052925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Afonine PV, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, Adams PD. The Phenix refinement framework. CCP Newsletter 2005 [Google Scholar]

- Afonine PV, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, Echols N, Headd JJ, Moriarty NW, Mustyakimov M, Terwilliger TC, Urzhumtsev A, Zwart PH, Adams PD. Towards automated crystallographic structure refinement with phenix refine. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2012;68:352–367. doi: 10.1107/S0907444912001308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrade KR, Boratto PPVM, Rodrigues FP, Silva LCF, Dornas FP, Pilotto MR, La Scola B, Almeida GMF, Kroon EG, Abrahão JS. Oysters as hot spots for mimivirus isolation. Arch Virol. 2014:1–6. doi: 10.1007/s00705-014-2257-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arisaka F, Kanamaru S, Leiman P, Rossmann MG. The tail lysozyme complex of bacteriophage T4. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2003;35:16–21. doi: 10.1016/s1357-2725(02)00098-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyer M, Azza S, Barrassi L, Klose T, Campocasso A, Pagnier I, Fournous G, Borg A, Robert C, Zhang X, et al. Mimivirus shows dramatic genome reduction after intraamoebal culture. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:10296–10301. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1101118108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavener DR. GMC oxidoreductases. A newly defined family of homologous proteins with diverse catalytic activities. J Mol Biol. 1992;223:811–814. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(92)90992-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Castro C, Molinaro A, Piacente F, Gurnon JR, Sturiale L, Palmigiano A, Lanzetta R, Parrilli M, Garozzo D, Tonetti MG, et al. Structure of N-linked oligosaccharides attached to chlorovirus PBCV-1 major capsid protein reveals unusual class of complex N-glycans. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110:13956–13960. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1313005110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimaio F, Terwilliger TC, Read RJ, Wlodawer A, Oberdorfer G, Wagner U, Valkov E, Alon A, Fass D, Axelrod HL, et al. Improved molecular replacement by density- and energy-guided protein structure optimization. Nature. 2011;473:540–543. doi: 10.1038/nature09964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doubayashi D, Ootake T, Maeda Y, Oki M, Tokunaga Y, Sakurai A, Nagaosa Y, Mikami B, Uchida H. Formate oxidase, an enzyme of the glucose-methanol-choline oxidoreductase family, has a His-Arg pair and 8-formyl-FAD at the catalytic site. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 2011;75:1662–1667. doi: 10.1271/bbb.110153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernández IS, Ruíz-Dueñas FJ, Santillana E, Ferreira P, Martínez MJ, Martínez AT, Romero A. Novel structural features in the GMC family of oxidoreductases revealed by the crystal structure of fungal aryl-alcohol oxidase. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2009;65:1196–1205. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909035860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fokine A, Miroshnikov KA, Shneider MM, Mesyanzhinov VV, Rossmann MG. Structure of the bacteriophage phiKZ lytic transglycosylase gp144. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:7242–7250. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M709398200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glonti T, Chanishvili N, Taylor PW. Bacteriophage-derived enzyme that depolymerizes the alginic acid capsule associated with cystic fibrosis isolates of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Appl Microbiol. 2010;108:695–702. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2009.04469.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta R, Jung E, Gooley AA, Williams KL, Brunak S, Hansen J. Scanning the available Dictyostelium discoideum proteome for O-linked GlcNAc glycosylation sites using neural networks. Glycobiology. 1999;9:1009–1022. doi: 10.1093/glycob/9.10.1009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kabsch W. XDS. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2010;66:125–132. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909047337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanamaru S, Leiman PG, Kostyuchenko VA, Chipman PR, Mesyanzhinov VV, Arisaka F, Rossmann MG. Structure of the cell-puncturing device of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 2002;415:553–557. doi: 10.1038/415553a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kao SH, McClain WH. Baseplate protein of bacteriophage T4 with both structural and lytic functions. J Virol. 1980a;34:95–103. doi: 10.1128/jvi.34.1.95-103.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kao SH, McClain WH. Roles of bacteriophage T4 gene 5 and gene s products in cell lysis. J Virol. 1980b;34:104–107. doi: 10.1128/jvi.34.1.104-107.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiess M, Hecht HJ, Kalisz HM. Glucose oxidase from Penicillium amagasakiense. Eur J Biochem. 1998;252:90–99. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.1998.2520090.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krissinel E, Henrick K. Inference of macromolecular assemblies from crystalline state. J Mol Biol. 2007;372:774–797. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuznetsov YG, Klose T, Rossmann M, McPherson A. Morphogenesis of Mimivirus and its viral factories: an atomic force microscopy study of infected cells. J Virol. 2013;87:11200–11213. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01372-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuznetsov YG, Xiao C, Sun S, Raoult D, Rossmann M, McPherson A. Atomic force microscopy investigation of the giant Mimivirus. Virology. 2010;404:127–137. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2010.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- La Scola B, Audic S, Robert C, Jungang L, de Lamballerie X, Drancourt M, Birtles R, Claverie JM, Raoult D. A giant virus in amoebae. Science. 2003;299:2033. doi: 10.1126/science.1081867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- La Scola B, Desnues C, Pagnier I, Robert C, Barrassi L, Fournous G, Merchat M, Suzan-Monti M, Forterre P, Koonin E, et al. The virophage as a unique parasite of the giant Mimivirus. Nature. 2008;455:100–104. doi: 10.1038/nature07218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laskowski RA, Swindells MB. LigPlot+: multiple ligand-protein interaction diagrams for drug discovery. J Chem Inf Model. 2011;51:2778–2786. doi: 10.1021/ci200227u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Vrielink A, Brick P, Blow DM. Crystal structure of cholesterol oxidase complexed with a steroid substrate: implications for flavin adenine dinucleotide dependent alcohol oxidases. Biochemistry. 1993;32:11507–11515. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathews FS. New flavoenzymes. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 1991;1:954–967. [Google Scholar]

- Mattevi A. To be or not to be an oxidase: challenging the oxygen reactivity of flavoenzymes. Trends Biochem Sci. 2006;31:276–283. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2006.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCoy AJ, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, Adams PD, Winn MD, Storoni LC, Read RJ. Phaser crystallographic software. J Appl Crystallogr. 2007;40:658–674. doi: 10.1107/S0021889807021206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miroshnikov KA, Faizullina NM, Sykilinda NN, Mesyanzhinov VV. Properties of the endolytic transglycosylase encoded by gene 144 of Pseudomonas aeruginosa bacteriophage phiKZ. Biochemistry (Moscow) 2006;71:300–305. doi: 10.1134/s0006297906030102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nandhagopal N, Simpson AA, Gurnon JR, Yan X, Baker TS, Graves MV, van Etten JL, Van Etten JL, Rossmann MG. The structure and evolution of the major capsid protein of a large, lipid-containing DNA virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:14758–14763. doi: 10.1073/pnas.232580699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otwinowski Z, Minor W. Macromolecular Crystallography. Elsevier; 1997. Processing of X-ray diffraction data collected in oscillation mode; pp. 307–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piacente F, Marin M, Molinaro A, De Castro C, Seltzer V, Salis A, Damonte G, Bernardi C, Claverie JM, Abergel C, et al. Giant DNA virus Mimivirus encodes pathway for biosynthesis of unusual sugar 4-amino-4,6-dideoxy-D-glucose (Viosamine) J Biol Chem. 2012;287:3009–3018. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.314559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollegioni L, Wels G, Pilone MS, Ghisla S. Kinetic mechanisms of cholesterol oxidase from Streptomyces hygroscopicus and Brevibacterium sterolicum. Eur J Biochem. 1999;264:140–151. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.1999.00586.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Que Q, Li Y, Wang IN, Lane LC, Chaney WG, van Etten JL, Van Etten JL. Protein glycosylation and myristylation in Chlorella virus PBCV-1 and its antigenic variants. Virology. 1994;203:320–327. doi: 10.1006/viro.1994.1490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raoult D. The 1.2-megabase genome sequence of Mimivirus. Science. 2004;306:1344–1350. doi: 10.1126/science.1101485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raoult D, La Scola B, Birtles R. The discovery and characterization of Mimivirus, the largest known virus and putative pneumonia agent. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;45:95–102. doi: 10.1086/518608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renesto P, Abergel C, Decloquement P, Moinier D, Azza S, Ogata H, Fourquet P, Gorvel JP, Claverie JM. Mimivirus giant particles incorporate a large fraction of anonymous and unique gene products. J Virol. 2006;80:11678–11685. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00940-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson JS. Handedness of crossover connections in beta sheets. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1976;73:2619–2623. doi: 10.1073/pnas.73.8.2619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossmann MG, Moras D, Olsen KW. Chemical and biological evolution of nucleotide-binding protein. Nature. 1974;250:194–199. doi: 10.1038/250194a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan TC, Spadiut O, Wongnate T, Sucharitakul J, Krondorfer I, Sygmund C, Haltrich D, Chaiyen P, Peterbauer CK, Divne C. The 1.6 Å crystal structure of pyranose dehydrogenase from Agaricus meleagris rationalizes substrate specificity and reveals a flavin intermediate. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e53567. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0053567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terwilliger TC, Dimaio F, Read RJ, Baker D, Bunkóczi G, Adams PD, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, Afonine PV, Echols N. phenix.mr_rosetta: molecular replacement and model rebuilding with Phenix and Rosetta. J Struct Funct Genomics. 2012;13:81–90. doi: 10.1007/s10969-012-9129-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wohlfahrt G, Witt S, Hendle J, Schomburg D, Kalisz HM, Hecht HJ. 1.8 and 1.9 Å resolution structures of the Penicillium amagasakiense and Aspergillus niger glucose oxidases as a basis for modelling substrate complexes. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 1999;55:969–977. doi: 10.1107/s0907444999003431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiang Y, Morais MC, Cohen DN, Bowman VD, Anderson DL, Rossmann MG. Crystal and cryoEM structural studies of a cell wall degrading enzyme in the bacteriophage phi29 tail. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:9552–9557. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0803787105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao C, Chipman PR, Battisti AJ, Bowman VD, Renesto P, Raoult D, Rossmann MG. Cryo-electron microscopy of the giant Mimivirus. J Mol Biol. 2005;353:493–496. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.08.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao C, Kuznetsov YG, Sun S, Hafenstein SL, Kostyuchenko VA, Chipman PR, Suzan-Monti M, Raoult D, McPherson A, Rossmann MG. Structural studies of the giant Mimivirus. PLoS Biol. 2009;7:e92. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan J, Mao J, Mao J, Xie J. Bacteriophage polysaccharide depolymerases and biomedical applications. BioDrugs. 2014;28:265–274. doi: 10.1007/s40259-013-0081-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zauberman N, Mutsafi Y, Halevy DB, Shimoni E, Klein E, Xiao C, Sun S, Minsky A. Distinct DNA exit and packaging portals in the virus Acanthamoeba polyphaga Mimivirus. PLoS Biol. 2008;6:e114. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0060114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X, Xiang Y, Dunigan DD, Klose T, Chipman PR, van Etten JL, Van Etten JL, Rossmann MG. Three-dimensional structure and function of the Paramecium bursaria chlorella virus capsid. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:14837–14842. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1107847108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]