Abstract

Hydrogen sulfide (H2S), a gaseous species produced by both bacteria and higher eukaryotic organisms, including mammalian vertebrates, has attracted attention in recent years for its contributions to human health and disease. H2S has been proposed as a cytoprotectant and gasotransmitter in many tissue types, including mediating vascular tone in blood vessels as well as neuromodulation in the brain. The molecular mechanisms dictating how H2S affects cellular signaling and other physiological events remain insufficiently understood. Furthermore, the involvement of H2S in metal-binding interactions and formation of related RSS such as sulfane sulfur may contribute to other distinct signaling pathways. Owing to its widespread biological roles and unique chemical properties, H2S is an appealing target for chemical biology approaches to elucidate its production, trafficking, and downstream function. In this context, reaction-based fluorescent probes offer a versatile set of screening tools to visualize H2S pools in living systems. Three main strategies used in molecular probe development for H2S detection include azide and nitro group reduction, nucleophilic attack, and CuS precipitation. Each of these approaches exploit the strong nucleophilicity and reducing potency of H2S to achieve selectivity over other biothiols. In addition, a variety of methods have been developed for the detection of other reactive sulfur species (RSS), including sulfite and bisulfite, as well as sulfane sulfur species and related modifications such as S-nitrosothiols. Access to this growing chemical toolbox of new molecular probes for H2S and related RSS sets the stage for applying these developing technologies to probe reactive sulfur biology in living systems.

1. Introduction

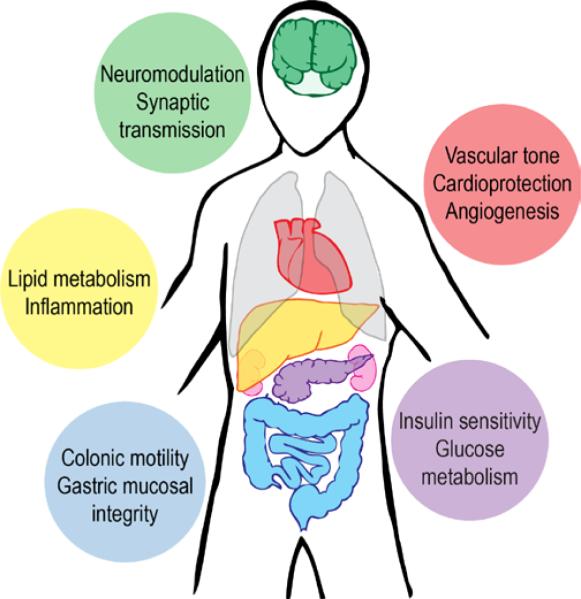

Biothiols are essential molecules in the cell, playing critical roles as antioxidants during injury and oxidative stress, as chelators for binding and interacting with metals, and as signaling agents. Hydrogen sulfide (H2S), the simplest biothiol, is produced endogenously in humans through both enzymatic and non-enzymatic processes. H2S can exist as a foul-smelling gas or dissolved in aqueous solution, primarily as the monoanionic form, HS−. H2S and other reactive sulfur species (RSS) contribute to a broad array of physiological responses to maintain cellular health. RSS are active as antioxidants and signaling agents in a variety of tissue types,1 including the liver,2 gastrointestinal system,3,4,5 pancreas,6 brain,7 and circulatory system8,9,10 (Fig. 1). On the other hand, studies have established that unregulated, abnormal levels of H2S may contribute to disease, as observed in models of Huntington's,11 Parkinson's,12 and Alzheimer's13 disease. Despite the many physiological effects of H2S in cellular and whole animal studies, precise molecular targets of H2S are still being unraveled and remain an important goal.

Figure 1.

Selected roles of H2S in human physiology. H2S produced throughout the human body modulates signaling processes in a variety of tissues, including the brain, cardiovascular system, liver, endocrine system, and gastrointestinal system.

At the molecular level, H2S exhibits unique chemical characteristics, acting as both a good reducing agent and a good nucleophile. These nucleophilic properties may help elucidate its signaling capabilities, with recent identification of potential electrophilic targets such as 8-nitro-cGMP.14 H2S can also react with oxidized thiols, generating reactive persulfides,15 as well as interact reversibly with metal centers.16,17 Because of this potent chemical reactivity, the signaling roles of H2S are diverse,18,19,20,21 ranging from oxygen sensing22 to modulation of phosphorylation events.23 In particular, research by several laboratories, including the Snyder and Tonks groups, has shown that reversible sulfhydration of cysteine residues has the potential to alter the activities of some enzymes,23,24 including protein tyrosines phosphatases25 and ATP-sensitive potassium channels.10 In this context, H2S alone may not be responsible for all of the observed downstream physiological effects. Indeed, emerging studies suggest that related RSS such as sulfane sulfur, as well as the metabolism of H2S to other species, may help explain the diverse roles for this simple thiol.26

Considering the challenges of measuring this volatile, reactive small molecule in living systems, the biologically relevant concentrations of H2S have been debated. 27 As such, the development of new technologies to better study H2S and related RSS in live cells, tissues, and whole animals is critical to gaining a more holistic understanding of how these transient chemical species contribute to physiology and pathology. Traditional analytical techniques such as colorimetric assays and gas chromatography have provided useful bulk measurements of biologically-produced H2S, but selective and sensitive detection of H2S generation within intact, living cells and tissues has proven more difficult. To meet this challenge, we and others in the field have pursued a synthetic organic methods approach based on a fundamental understanding of molecular structure and function to develop reaction-based probes for sensitive, selective, and biocompatible fluorescence detection of H2S in living systems. 28 In this review, we summarize the rapid progress of fluorescent H2S probe development, focusing on the past 4 years and highlighting a variety of inventive strategies to achieve good reactivity and selectivity for H2S over other biothiols. Organelle-targeted, cell-trappable, two-photon, and ratiometric probes have been reported, spanning a wide spectrum of emission colors. Finally, the advent of selective reporters that can differentiate between H2S and higher RSS provides new opportunities to probe the complex interplay between these species in biological systems.

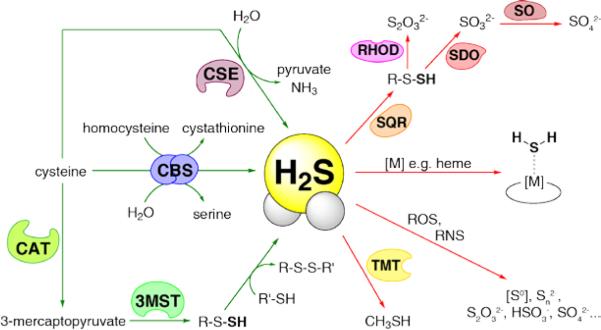

1.1. Reactive sulfur species (RSS) biochemistry

The production and metabolism of H2S in mammalian cells are regulated by enzymes that are distributed throughout virtually every tissue type. The enzymes of the transsulfuration pathway, cystathionine gamma lyase (CSE) and cystathionine beta synthase (CBS), ensure appropriate levels of cysteine and homocysteine are maintained in the cell.29 The interconversion of these sulfur-containing substrates can lead to H2S production by several linked pathways (Fig. 2). 30 Besides CSE and CBS, the combined action of two other enzymes, cysteine aminotransferase (CAT) and 3-mercaptopyruvate sulfurtransferase (3-MST), can also generate H2S.31 Mice deficient in CSE display elevated blood pressure,8 and CBS knockout mice exhibit retarded growth, cardiovascular problems, and poor survival.32,33

Figure 2.

Selected biochemical pathways for the production and metabolism of H2S in mammalian systems.

Given its potent reactivity, organisms have developed efficient means for regulation of H2S levels in tissue.34,35 At sufficient levels, H2S is highly toxic, binding to hemeproteins such as cytochrome c oxidase and inhibiting the electron transport chain. 36, 37 In the body, major detoxification occurs in the gut, which is populated by H2S-producing enterobacteria.5,38 At the cellular level, mitochondrial detoxification of H2S by sulfur quinone reductase (SQR), rhodanese (RHOD), and sulfur dioxgenase (SDO) converts H2S into sulfite and thiosulfate. Subsequent action by sulfite oxidase (SO) produces sulfate as a final product. Other metabolic pathways include methylation of H2S to methanethiol (CH3SH) by thiol S-methyltransferase (TMT) and oxidation pathways. Non-enzymatic reactions involving ROS and RNS may produce many different oxidized sulfur species such as elemental sulfur and bisulfite,39 while metal centers may act as both sources and sinks for H2S owing to reversible binding interactions.40 The effects of H2S on metalloproteins containing iron41,42 and zinc43 have been explored in terms of sulfide toxicity, transport, and redox signaling.

1.2. Scope of the review

This review will begin with an examination of current fluorescent probes used for molecular imaging of H2S in living systems. Owing to space limitations, the assortment of highly sensitive colorimetric44,45 and HPLC-based probes such as monobromobimane27,46 that have been developed to improve upon existing classical H2S detection methods such as the methylene blue assay47 will not be covered in this review. In addition, fluorescent H2S probes that have not yet been applied to cellular systems and probes that display a decrease in fluorescence upon treatment with H2S are also generally not described in this review due to the difficulty in detecting changes in analyte when such turn-off probes are applied to cells. This review places emphasis on probes that have been applied to the detection of RSS in living systems (Fig. 3). Literature reviews of other techniques for H2S and sulfide detection, including electrode-based sensors 48 and chromatographic methods, are recommended. 49, 50, 51 On account of the rapid growth of the field, we also direct the readers to other recent reviews on fluorescent probes for H2S detection.52,53,54,55

Figure 3.

Selected examples of live-cell imaging using chemoselective fluorescent H2S and sulfane sulfur probes. (A) Detection of H2S in HeLa cells loaded with WSP-5 and treated with 100 μM NaHS. Reprinted (adapted) with permission from ref. 127, Copyright 2014 Wiley-VCH. (B) Detection of endogenous H2S production in human umbilical vein endothelial cells upon stimulation with vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) using SF7-AM. Reprinted (adapted) with permission from ref. 68, Copyright 2013 National Academy of Sciences. (C) Visualizing attenuated H2S production using the ratiometric probe SHS-M2 in DJ-1 knockout astrocytes, a model of Parkinson's disease. Reprinted (adapted) with permission from ref. 93, Copyright 2013 American Chemical Society. (D) Detection of 100 μM H2S2 in HeLa cells by DSP-3. Reprinted (adapted) with permission from ref. 152, Copyright 2014 American Chemical Society.

The second part of this review will focus on fluorescent probes for higher reactive sulfur species, including sulfane sulfur species, hydrogen polysulfides, and metabolites of H2S like sulfite and bisulfite. We also survey chemical tools that have been developed for probing RSS-mediated modifications to proteins, such as sulfenic acids, persulfides, and S-nitrosothiols.

2. H2S probes

As the smallest thiol, H2S can act as a simple reductant as well as a good nucleophile for a variety of transformations in organic chemistry. Indeed, H2S, sodium hydrosulfide, and sodium sulfide have been used as reducing agents for synthesis since the 1800s.56,57,58 These RSS have also been used as nucleophilic sulfur reagents to install sulfur functionalities onto various molecular scaffolds.59,60,61 The pKa of H2S is 7, and as such an estimated two-thirds of this RSS will exist as the anionic HS−, an excellent nucleophile, in aqueous solution at physiological pH. Additionally, analytical chemists have employed hydrogen sulfide for centuries in the gravimetric analysis of metals, such as copper.62,63 These facets of H2S in analytical and organic chemistry provide a starting point for the design of fluorescent probes that respond selectively and sensitively toward this RSS. The ever-expanding toolbox of reaction-based probes employ three primary strategies for H2S detection: reduction of azides to amines, nucleophilic reaction, and copper sulfide precipitation.

2.1. Azide reduction

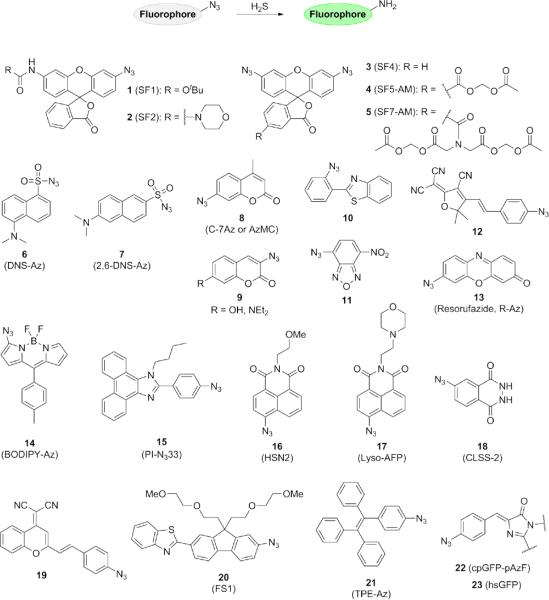

Organic azides have been used extensively in chemical biology as a bioorthogonal functional group.64 Their compatibility with living cellular systems combined with the relative synthetic ease of installing azide moieties onto a wide array of amine-containing fluorophores has led to the rapid preparation of a wide variety of fluorescent azide-based probes (Fig. 4). H2S detection occurs by the chemoselective reduction of azides to amines by this RSS. The first concomitant reports of azide-based fluorescent probes that could be used for H2S detection in live cells were rhodamine-based Sulfidefluor (SF) probes 1-2 functionalized with aryl azides by Lippert and Chang65 and dansyl probe 6 featuring a sulfonyl azide by Wang et al.66 The Wang group has since developed a 2,6-dansyl azide structural isomer of the original probe, which exhibits improved solubility and selectivity.67 Chang and Lippert have also expanded upon the SF series of probes, synthesizing bis-azido rhodamines 3-5 for lowered background signal and appending acetoxymethyl (AM) ester trapping groups for enhanced cellular retention and trappability.68 Similar bisazido carboxyrhodamine derivatives have also been prepared by Sun's group.69 Using these second-generation H2S probes, endogenous H2S production in a model system of angiogenesis was visualized.

Figure 4.

Structures of fluorescent H2S probes based on the chemoselective reduction of aryl azides to amines.

Incorporation of the azide trigger onto a variety of other fluorophore scaffolds has provided access to probes in a range of colors. Reporters for H2S based on coumarin (8-9),70,71,72 2-(2-aminophenyl)benzothiazole (10), 73 7-nitrobenz-2-oxa-1,3-diazole (11), 74 dicyanomethylenedihydrofuran (12), 75 resorufamine (13), 76 BODIPY (14), 77 phenanthroimidazole (15), 78 and the 1,8-naphthalimide scaffold (16) 79 have been described, including a lysosomally-targeted derivative (17).80 The Pluth laboratory has also developed the first chemiluminescent H2S probe 18 based on an azido derivative of luminol, which can be used to detect enzymatically-produced H2S in vitro.81 A near-infrared (near-IR) probe 19 based on dicyanomethylene-4H-chromene that can also be used for two-photon imaging was reported simultaneously by Xu and Peng and their co-workers.82,83 Two-photon probes such as 20 have been synthesized,84 as well as a tunable, aggregation induced emission (AIE) probe 21 based on tetraphenylethene developed by the Tang group.85 The azide moiety has even been extended to genetically-encoded reporters 22-23, as the Ai laboratory used site-specific artificial amino acid incorporation to install a p-azidophenylalanine residue at Tyr66 in cpGFP. 86 An improved version of this probe, hsGFP, was also recently reported. 87 Using a new superfolder GFP template, Chen and Ai obtained a new genetically-encoded H2S reporter with a larger dynamic range, improved selectivity, and more effective formation of the mature chromophore.

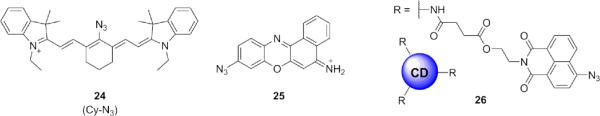

Several ratiometric probes have been reported that exploit the electronic differences between the azide and amino functionalities to achieve a shift in fluorescence emission (Fig. 5). Ratiometric imaging methods rely upon fluorescent probes that display fluorescence emission or excitation a two different wavelengths; in response to varying levels of analyte, these fluorescence peaks change in direct proportion to one another, independent of dye concentration. The ratiometric character of these probes can correct for differences in dye loading, photobleaching, and other factors that may complicate imaging results, thereby enabling acquisition of semi-quantitative data. Ratiometric probes are therefore of great interest to the probe development community given these special spectroscopic properties. The Han group utilized an azide-functionalized cyanine dye in probe 24 where the parent probe fluoresces at 710 nm, but upon its reduction to the amine the emission maximum shifts to 750 nm.88 A related ratiometric cresyl violet probe 25 displayed a bathochromic shift in emission from 566 to 620 nm and was applied to both cells and zebrafish to detect exogenous H2S using NaHS as the sulfide source. 89 A third ratiometric probe 26 was reported using an 4-azido-1,8-naphthalimide dye as a FRET acceptor conjugated to a carbon dot.90 The carbon dot emits at 425 nm and serves as the FRET donor; once the aryl azide on the fluorophore is reduced by H2S to an aniline, the probe emits at 526 nm.

Figure 5.

Structures of ratiometric H2S probes utilizing azide reduction to shift fluorescence emission.

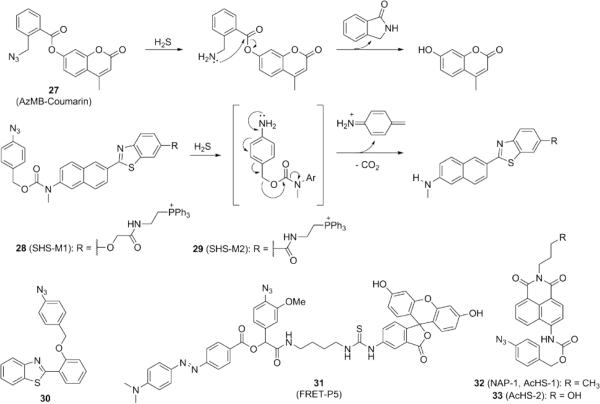

2.1.1. Self-immolative linkers

The selective reduction of azides to amines by H2S has also been adapted to reaction-based imaging probes possessing self-immolative linkers, which are triggered upon formation of an amino group (Fig. 6). A coumarin-based probe 27 operates by H2S-mediated reduction of a benzylic azide, which generates a primary amine that can subsequently perform intramolecular attack on the ester carbonyl to release 8-hydroxycoumarin.91 Other probes have utilized the azide to mask dyes for 1,6-elimination, a strategy that has been previously explored for prodrug delivery.92 Reduction of the aryl azide to an aniline is followed by azaquinone methide formation and release of the fluorophore. Using this approach, Cho and co-workers reported the development of two-photon, ratiometric, mitochondrially-targeted probes 28-29, which was successfully applied to live cells and used to detect decreases in endogenous H2S in astrocytes lacking DJ-1, a gene involved in Parkinson's disease.93 Incorporation of the p-azidobenzyl group onto 2-(2’-hydroxyphenyl)benzothiazole (HBT) affords an alternative probe 30 using a similar strategy.94 A series of ratiometric FRET probes (31, FRET-P1 through 5) developed by the Tang laboratory employs fluorescein and [4′-(N,N′-dimethylamino)phenylazo]benzoyl (DABCYL) as a FRET pair, tethered by a thiourea linkage.95 Incorporation of an electron-donating methoxy group ortho to the azide increases the kinetics of the 1,6-elimination for azaquinone methides as previously demonstrated by the Phillips group.96 Ratiometric probes 32 and 33 feature a pazidobenzyl group attached to 1,8-naphthalimide fluorophore by a carbamate linkage, which then undergoes 1,6-elimination to release an azaquinone methide97,98 with the resulting change in electronics giving rise to a shift in fluorescence emission. Such probes are useful for biological inquiry, but precautions must be taken to account for the release of azaquinone methide, which may potentially have strong alkylating abilities in biological systems.99

Figure 6.

Structures of fluorescent H2S probes based on reduction of azide groups to amines, followed by self-immolative cleavage.

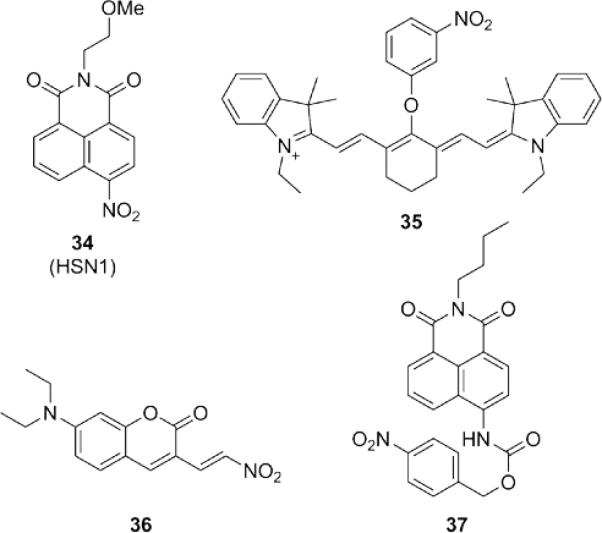

2.1.2. Nitro group reduction

Like azide reduction, reduction of nitro groups generates amino products, which display significantly different electronic properties. Installation of nitro groups onto fluorophores can thus be used as a strategy for H2S-selective probes (Fig. 7). The first of these probes by the Pluth group utilized the 1,8-naphthalimide scaffold to afford a fluorescent turn-on probe 34.79 The nitro group has been incorporated into cyanine dyes (35) 100 and coumarins (36)101 to yield fluorescent H2S probes in a variety of colors. Self-immolative linkers, similar to those described in the previous section, have been explored as well (37).102 Due to the potential sensitivity of nitro groups toward endogenous reductases,103,104 appropriate controls must accompany use of these probes in live cell systems to confirm H2S production is responsible for the observed response.

Figure 7.

Structures of fluorescent H2S probes based on reduction of nitro groups to amines.

2.2. Nucleophilic attack strategies

H2S is an excellent nucleophile, existing predominantly as HS- at physiological pH and therefore displaying higher nucleophilicity compared to many other thiols found in the cell. As such, several types of platforms have been applied to take advantage of this nucleophilic reactivity. These probe designs typically incorporate electrophilic functionalities that can be transformed in the presence of H2S. Two strategies, the thiolysis of aryl nitro groups and the disruption of conjugated systems, exploit the selective addition of HS− to a single electrophilic position on the probe scaffold. A major challenge associated with the detection of H2S is achieving selective reactivity over other thiols present in the cellular environment, specifically glutathione and cysteine, which are typically present in millimolar concentrations. The nucleophilic properties of H2S, particularly its ability to perform two consecutive nucleophilic reactions, has provided inspiration for probes that react robustly toward H2S and display very limited response in the presence of other biothiols. These reporters, broadly categorized by their use of a disulfide exchange mechanism or tandem Michael addition strategy, incorporate two electrophilic centers into their design.

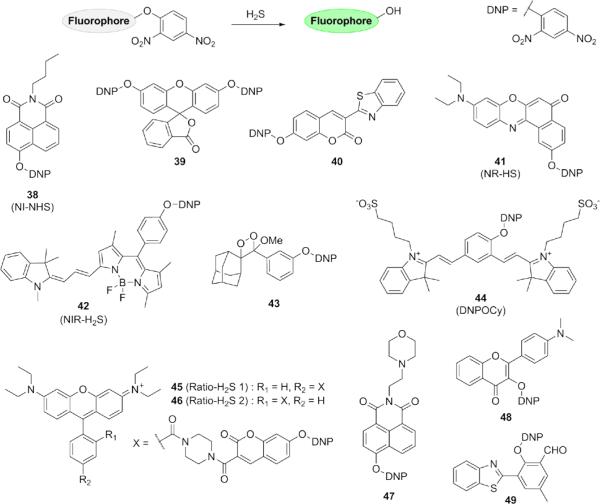

2.2.1. Aryl nitro thiolysis

The 2,4-dinitrophenyl (DNP) ether moiety has been employed extensively as a protecting group for tyrosines in peptide synthesis, with thiolytic cleavage achieved by treatment with 2-mercaptoethanol. 105, 106 Incorporation of the DNP functional group onto 1,8-naphthalimide (38),107 fluorescein (39),108 coumarin (40),109 Nile Red (41),110 near-IR BODIPY (42),111 and other fluorophore scaffolds has yielded H2S probes in a wide range of emission colors (Fig. 8). A chemiluminescent probe 43 has also been reported, consisting of a stable adamantyl dioxetane that decomposes upon H2S-mediated cleavage of the DNP ether.112 A near-IR H2S indicator 44 based on a cyanine dye was prepared and successfully applied to living cells, displaying ratiometric emission at 555 and 695 nm. 113 A pair of H2S probes 45-46 with ratiometric excitation was also reported, featuring a DNP-capped hydroxycoumarin linked to tetraethylrhodamine by a piperazine group.114 A lysosomal H2S reporter 47 utilizing an N-alkyl morpholino group for targeting,115 as well as an excited state intramolecular proton transfer (ESIPT) probe 48, have appeared in recent years.116 A particularly interesting design by Huang and co-workers involves incorporation of an aldehyde group onto an ESIPT fluorophore to give probe 49 for fast reaction with H2S followed by subsequent thiolysis of the proximal DNP ether.117

Figure 8.

Structures of fluorescent H2S probes based on thiolysis of dinitrophenyl ethers.

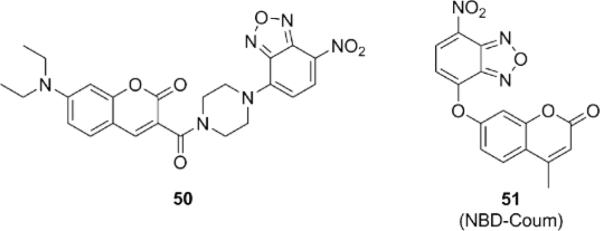

In addition to DNP, other nitro aryl groups such as nitrobenzofuran (NBD) have been examined for their ability to undergo thiolysis by H2S via a nucleophilic aromatic substitution (SNAr) mechanism (Fig. 9). A coumarin based probe 50 attached to NBD via a piperazine linked was first reported by Wei et al. and used to image exogenous H2S in cells.118 The Pluth group has previously reported selective probes for colorimetric assays using the NBD scaffold.44 Recently, Pluth and coworkers have expanded upon their mechanistic studies to develop a fluorescent NBD-coumarin probe 51 that would display different emission profiles in the presence of H2S or biothiols, allowing for spectral differentiation of these species.119

Figure 9.

Structures of fluorescent H2S probes based on nucleophilic aromatic substitution of nitrobenzofuran.

2.2.2. Nucleophilic addition to conjugated systems

As a good nucleophile, HS− can undergo addition to fluorescent molecules with electrophilic centers such as cyanine dyes. This strategy has been harnessed for the development of ratiometric H2S probes 52 and 53, which rely on disruption of an extended pi system to shift the fluorescence emission (Fig. 10).120,121 These ratiometric indicators have been successfully utilized in live cells, including applications in MCF-7 and HeLa cells, with probe 52 localizing to mitochondria. Treating live cells with NaHS produced changes in the fluorescence ratios for these probes, demonstrating successful detection of exogenous H2S. Effective use of this strategy must account for possible cross-reactivity with other nucleophilic thiols, as related probes have been used previously for detection of biothiols.122,123 For these ratiometric H2S probes, it has been suggested that the H2S selectivity may be influenced by unfavorable electrostatic interactions between the positively-charged probe and the ammonium groups of zwitterionic cysteine and glutathione.121 Ratiometric H2S probes are powerful tools for biological imaging experiments, and their continued development will enable further elucidation of H2S biology in complex models.

Figure 10.

Structures of ratiometric H2S probes based on disruption of the conjugated π-system in a fluorophore and mechanism of their reaction with H2S.

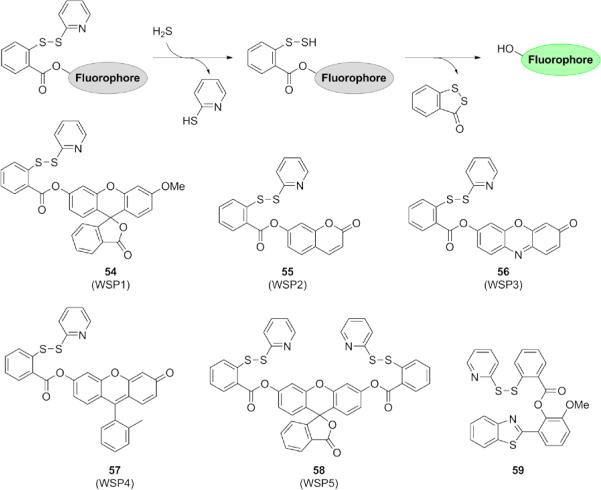

2.2.3. Disulfide exchange

After nucleophilic attack of H2S on electrophilic carbon, nitrogen, and sulfur centers, the resulting intermediate is also a thiol species, which can potentially undergo a second nucleophilic addition to a different position within a given probe molecule. This double nucleophilic character is unique to H2S over other biologically relevant thiols. As such, several groups have designed probes that take advantage of this special reactivity and therefore offer excellent selectivity for H2S over other RSS (Fig. 11). Moreover, the formation of mixed disulfides is well-precedented in vitro and in the cell. 124, 125 The Xian group has harnessed disulfide exchange for the development of the first Washington State Probe, WSP-1 (54). 126 Displacement of the 2-thiopyridine affords a reactive, nucleophilic hydropersulfide, which readily undergoes by intramolecular cyclization to release a disulfide product and 3-O-methylfluorescein as the fluorophore. Extension of this strategy to a series of probes (55-58) in a variety of colors demonstrates the versatility of this trigger and its ready application to coumarin, resorufin, and fluorescein-based scaffolds. 127 These probes are stable to esterases and display excellent selectivity for H2S over other biothiols, as mixed disulfides formed between these probes and intracellular glutathione are reversible, meaning that the resulting disulfide cannot undergo cyclization. A related ratiometric disulfide exchange ESIPT probe 59 was developed based on HBT.128

Figure 11.

Structures of H2S probes utilizing the disulfide exchange mechanism to form a reactive hydropersulfide that undergoes nucleophilic addition to release the fluorophore.

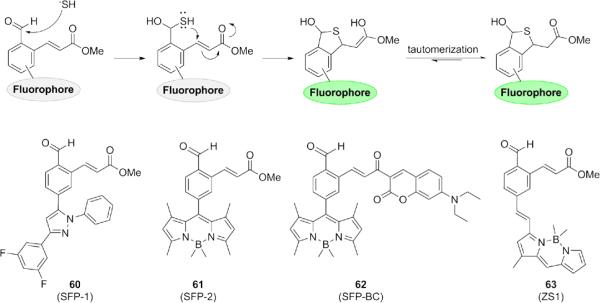

2.2.4. Tandem Michael addition

Another approach that has exploited the double nucleophilic ability of H2S is the tandem Michael addition strategy, first reported by He, Zhao, and co-workers. These sulfide-selective fluorescent probes (60-61) are based on the 1,3,5-triaryl-2-pyrazoline and BODIPY scaffolds (Fig. 12).129 Related BODIPY derivatives 62-63 have been reported.130,131 These H2S probes feature an aldehyde functionality which serves as the site of initial nucleophilic attack. The resulting hemithioacetal then undergoes nucleophilic 1,4-addition to the α,β-unsaturated ester, cyclizing and producing a turn-on fluorescent response. Like the disulfide exchange strategy, these probes are very selective for H2S over other biothiols found in the cell due to the inability of other thiols to perform the second nucleophilic attack required for cyclization. These probes allow for ready imaging of H2S in live cellular systems. The Xian laboratory also showed this strategy could be modified to cleave the thioacetal cyclization product from the fluorophore in the last step (Fig. 13). Two probes 64-65 based on fluorescein have been designed using this strategy, incorporating two different Michael acceptors.132 A third probe 66 that uses a cyanine scaffold for ratiometric response has also been described.133

Figure 12.

Structures of fluorogenic probes containing α,β-unsaturated esters which undergo nucleophilic attack at two proximal electrophilic centers to trap H2S in the product.

Figure 13.

Structures of fluorogenic probes containing α,β-unsaturated esters which undergo nucleophilic attack at two proximal electrophilic centers, with elimination of a fluorescent molecule in the final step.

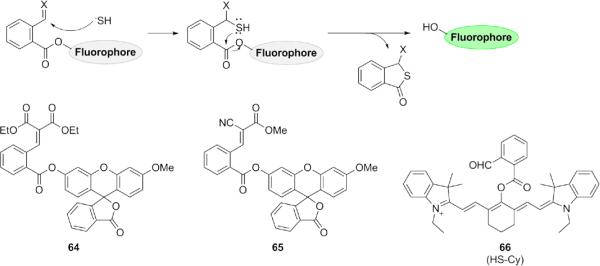

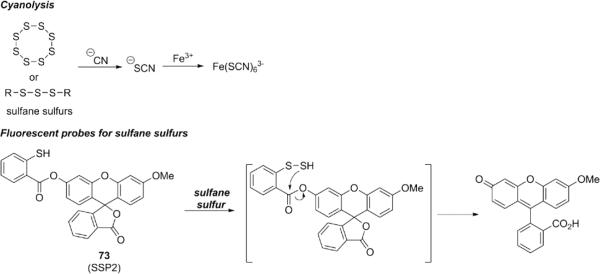

2.3. CuS precipitation

Precipitation of copper sulfide (CuS), a classical method for quantitative analysis of sulfide content, has been successfully adapted for fluorogenic H2S detection via the incorporation of copper-binding moieties onto fluorophores (Fig. 14).134 Nagano and co-workers applied this strategy to prepare copper-based dyes such as probe 67 for detection of H2S in living cells.135 When paramagnetic Cu2+ is bound to the cyclen azamacrocycle, fluorescence is quenched. Reaction of the copper ion with H2S causes precipitation of CuS, releasing the dye in a fluorescent, unbound state. Nagano's initial report astutely noted that the choice of azamacrocycle potentially affects the reactivity of the probe, particularly in terms of its selectivity toward H2S over other thiol species.135 Thus, screening of probe performance in the presence of other RSS is especially important, since alternate combinations of fluorophores and receptors exhibit different properties. Additional probes utilizing the CuS precipitation strategy have been reported for fluorescein (68-69),136,137 anthracene (70),138 and dimeric phenanthrene-fused dipyrromethene (71).139 A two-photon probe 72 consisting of a carbon nanodot functionalized with N-(2-aminoethyl)-N,N,N′-tris(pyridin-2-ylmethyl)ethane-1,2-diamine(TPEA), a ligand used for copper binding, was used to image exogenous H2S in model cellular systems and lung cancer tissue.140

Figure 14.

Structures of fluorescent probes using copper sulfide precipitation to afford a turn-on response.

3. Fluorescent probes for higher RSS

3.1. Sulfane sulfur species

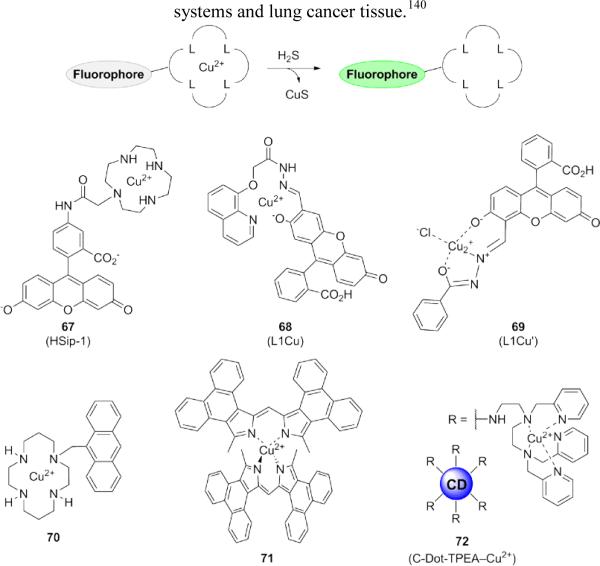

In addition to H2S, increasing attention is being paid to detection of higher-order RSS, as these reactive species are also of biological importance. In this context, sulfane sulfurs are common RSS of interest. Sulfane sulfur refers to a sulfur atom with six valence electrons but no charge (known as S0). A number of sulfane sulfur molecules exist in biological systems, including persulfides (R-S-SH), polysulfides (R-S-Sn-S-R, n>=1), hydrogen polysulfides (H2Sn, n>1), and protein-bound elemental sulfur.49,141-144 These RSS have unique biological activities such as modulating enzyme functions and participating in the synthesis of sulfur-containing vitamins and cofactors.145 More recent studies on H2S redox biology even suggest that sulfane sulfurs are the primary RSS signaling molecules downstream of H2S.15,145-149

Despite an increasing recognition of the importance of sulfane sulfurs in biological settings, their detection in living samples remains a challenge. Sulfane sulfurs possess a unique electrophilic character that can react with certain nucleophiles. For example, the traditional method for sulfane sulfur detection, i.e. cyanolysis, is based on the reaction with cyanide ion (CN−) to form thiocyanate (SCN−), which can be measured (by UV absorbance) as ferric thiocyanate (Fig. 15). 150 Taking advantage of this electrophilicity, several reaction-based fluorescent probes for sulfane sulfurs were developed recently by Xian and co-authors, 151 employing a thiophenol that reacts with sulfane sulfurs to form an Ar-S-SH intermediate, which subsequently undergoes an intramolecular cyclization to release the pendant fluorophore. Probes such as SSP2 (73) showed fast and highly selective turn-on fluorescence responses to sulfane sulfurs (including polysulfides and elemental sulfur) over other RSS such as cysteine, glutathione, and H2S with nM detection limits, and were effective in detecting both exogenous and endogenous sulfane sulfurs in cell imaging experiments.26 We note that although these probes can effectively identify sulfane sulfurs from other reactive sulfur species, they cannot differentiate each member in the sulfane sulfur family, for example polysulfides (the oxidized form of sulfane sulfurs) vs persulfides (the reduced form of sulfane sulfurs).

Figure 15.

Structures of fluorescent probes for sulfane sulfur.

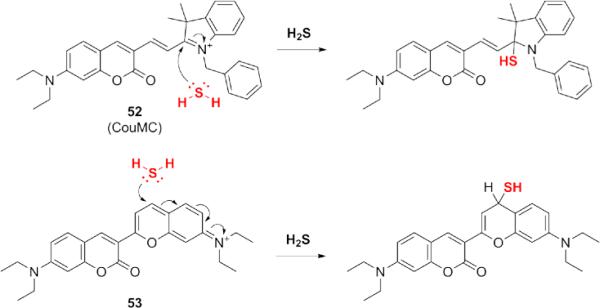

3.2. Fluorescent probes for hydrogen polysulfides

Hydrogen polysulfides (H2Sn, n > 1) are a particularly interesting class of sulfane sulfurs that merit special mention, as they can be considered oxidized forms or redox partners of H2S. It is likely that H2Sn and H2S co-exist in biological systems and work collectively to regulate sulfur redox balance. From a chemistry point-of-view, H2Sn should be more reactive than H2S owing in part to the α effect. For example, recent in vitro studies have revealed that H2Sn are much more potent in protein S-sulfhydration reactions compared to H S147-149 and suggest that some biological mechanisms that were originally attributed to H2S may proceed through H2Sn intermediates. H2Sn is a combination of hydrogen polysulfides in which hydrogen disulfide (H2S2) is the smallest and likely the most reactive species in dynamic equilibrium with other H2Sn. 147 Xian and co-workers exploited the two -SH groups in H2S2 to make 74,152 a probe where a 2-fluoro-5-nitro-benzoic ester can rapidly trap H2S2 and promote an intramolecular cyclization to release fluorescein (Fig. 16). This probe can also react with biothiols to form thioether products, but these compounds do not undergo cyclization and therefore do not yield an increase in fluorescent signal. More interestingly, such thioether products can further react with H2Sn (via the SN2Ar reaction) to give a turn-on fluorescent response, which confirms its selectivity. The detection limit of DSP-3 was determined to be 71 nM.

Figure 16.

Structures of fluorescent probes for hydrogen polysulfides.

3.3. Sulfite and bisulfite

Sulfur dioxide (SO2) is a well-known air pollutant and has been studied extensively in toxicology. However, more recent work has shown that this molecule is generated endogenously, mainly from sulfur-containing amino acids through biosynthetic pathways 153 - 155 such as transamination by aspartate aminotransferase (AAT).156 SO2 exhibits unique bioactivities such as vasodilatation and lowering of blood pressure.157-159 These observations have led to speculation that SO can be considered a gasotransmitter,156,160,161 and thus the detection of SO2 and its hydrated derivatives (sulfide and bisulfite) have attracted attention. SO2 is readily soluble in water (40 L SO2 [g] in 1 L H2O) and forms a very stable hydrated SO2 complex (SO2•H2O). As such, in aqueous environments the major chemical state of SO2 is molecular SO2, not H2SO3, the precursor of bisulfite (HSO3−) and sulfite (SO32−). 162 Hydrated SO2 and bisulfite/sulfite are distinct molecular species that exhibit distinct chemical and biological functions,163,164 but both hydrated SO2 and bisulfite/sulfite have been used in exploring the biological contributions of SO2; hydrated SO2 typically shows more potent activity than bisulfite/sulfite.161,163,164 Nevertheless, many studies on SO2 fluorescent probes center on detection of bisulfite/sulfite, not the molecular SO2.

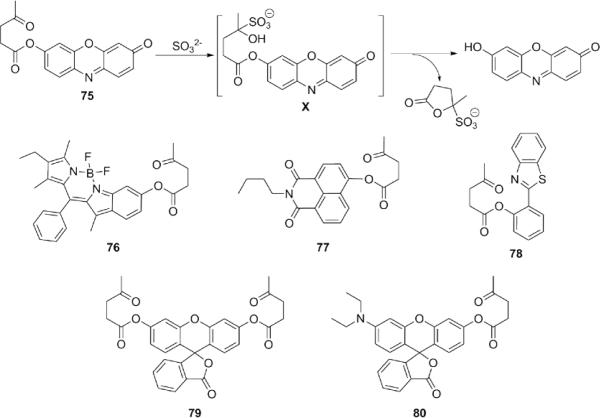

Exploiting the nucleophilicity of SO32−, Chang and colleagues reported the first fluorescent probe for its detection (Fig. 17).165 SO32− is proposed to react with the ketone group of 75 to form intermediate X, which then undergoes a fast cyclization to release the fluorophore.Both chromogenic and fluorogenic responses to SO32− in HEPES buffer (pH 7.0, 10 mM) containing 2% acetonitrile were observed with a detection limit of 49 μM, and this strategy was expanded to develop a family of SO32− reporters (76-80) that show good selectivity over other anions and RSS, including H2S. 166-170

Figure 17.

Structures of fluorescent probes for SO32−/HSO3− featuring γ-ketoester triggers.

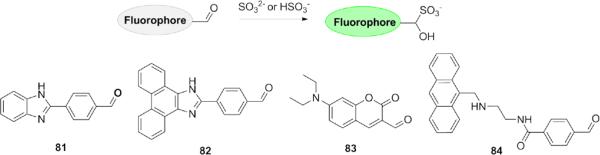

Aldehyde triggers for SO32−/HSO3−have also been used for detection of these RSS (Fig. 18). Reactions with SO32−/HSO3−result in a change in the electron acceptor strength and the concomitant charge transfer efficiency. For example, based on the difference of the intramolecular charge transfer (ICT), ratiometric probe 81 was found to be selective for HSO −3 in pH 4.6 NaAc-HAc buffer with a detection limit of 0.4 μM, 171 and related ICT-based probes (82-83) were effective for HSO −3 detection in pH 5 NaH2PO4/citric buffer and in HeLa cells.172,173 Fluorescent indicator 84 for SO32− based on the modulation of photoinduced electron transfer (PeT) was also reported; this probe was used to determine concentrations of SO32− in food or beverages.174

Figure 18.

Structures of fluorescent probes for SO32−/HSO3− utilizing aldehyde triggers.

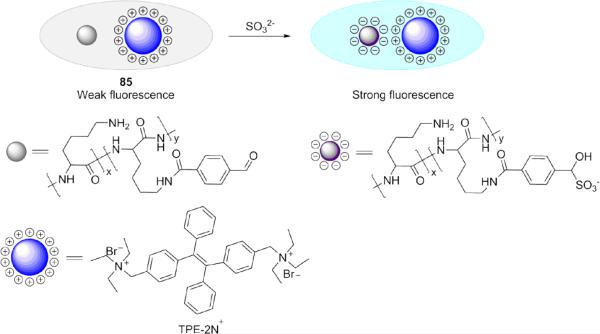

More recently, Wu and co-workers developed a water-soluble polylysine-based probe 85 for SO32− that induced charge generation and the aggregation induced emission (AIE) effects (Fig. 19). 175 The probe was consisted of a modified polylysine with aldehyde groups and positively charged fluorophores (TPE-2N+). After the aldehyde groups on polylysine chains reacted with SO32− (in pH 7.0 HEPES buffer), the resultant negatively charged groups formed complexes with TPE-2N+ and led to a fluorescence enhancement due to the AIE effects.

Figure 19.

Structure of a fluorescent probe for SO32−/HSO3− exploiting an aggregation induced emission strategy.

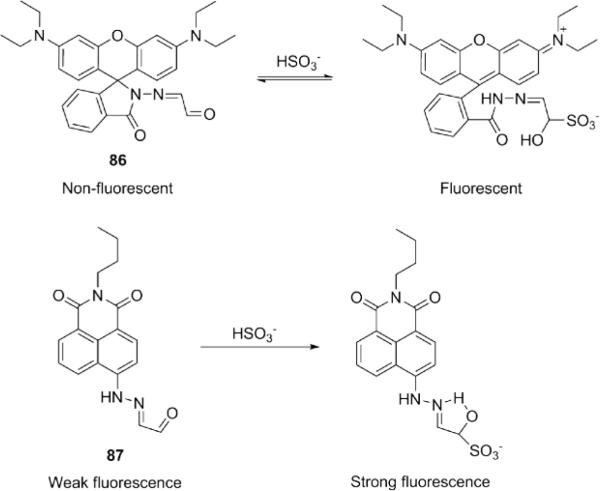

The reaction between glyoxal mono-hydrazone and HSO3− was also used in the design of fluorescent HSO3− probes (Fig. 20). In one example (probe 86), formation of the addition product led to spirolactam opening of rhodamine to turn on fluorescence in Na2HPO4-citric acid buffer (20 mM, pH 4.8) containing 10% ethanol with a detection limit of 0.89 μM. 176 In another example, probe 87 was weakly fluorescent owing to C=N isomerization-induced fluorescence quenching, 177 but reaction with HSO3− formed an intramolecular hydrogen bond which inhibited isomerization and led to fluorescence turn-on in acidic media (DMSO-acetate buffer, 100 mM, pH 5.0, 1:1, v/v).

Figure 20.

Structure of fluorescent probes for SO32−/HSO3− featuring glyoxal mono-hydrazone moieties.

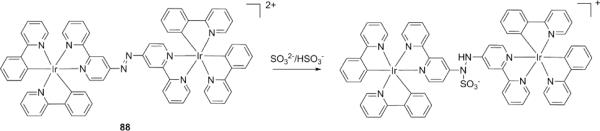

As described above, many aldehyde/ketone based probes require acidic medium for the detection, as in neutral buffers (or in organic solvents) these probes showed strong responses to biothiols (for example, probes 82, 83, 86, 87).178-181 In order to address this issue, fluorescent indicators based on nucleophilic additions to other double bonds (such as -N=N-, -C=N-, -C=C-) have been explored. For example, Chao and colleagues prepared a non-emissive dinuclear iridium(III) complex (88) bridged via an azo group (Fig. 21).182 The electron-withdrawing azo group can effectively quench the luminescence efficiency of 88 based on trapping electrons in the metal-to-ligand charge-transfer (MLCT) excited state. When 88 reacted with SO32−/HSO3− in HEPES buffer (10 mM, pH 7.5) containing 30% DMSO, a dramatic increase in the phosphorescence intensity at 600 nm was observed due to the addition-induced changes in the electronic and luminescent properties of the metal complex. The probe showed highly selective off-on response to SO32−/HSO3− over other RSS with a detection limit of 0.24 μM for SO32− and 0.14 μM for HSO3−. Moreover, 88 was applied to detection of both exogenous and endogenous SO32−/HSO3− in living cells.

Figure 21.

Structure of a fluorescent probe for SO32−/HSO3− based on a dinuclear iridium(III) complex.

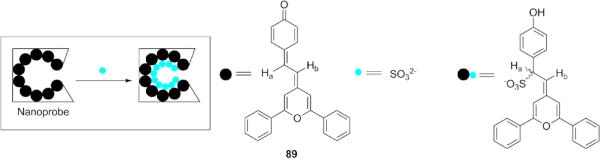

Martínez-Máñez and co-workers reported a chromofluorogenic nanoprobe for SO32− in food and environmental samples by using hydrophobic hybrid organic-inorganic silica nanoparticles loaded with probe 89, which can readily react with SO32− via 1,6-conjugated addition (Fig. 22) in HEPES buffer(30 mM, pH 7.5), causing a color change from blue to pale yellow with a detection limit of 0.32 ppm.183 The selectivity for SO32− was ascribed to the preferential inclusion of SO32− into the hydrophobic pockets in nanoparticles.

Figure 22.

Structure of a fluorescent nanoprobe for SO32−/HSO3− based on hybrid organic-inorganic silica nanoparticles.

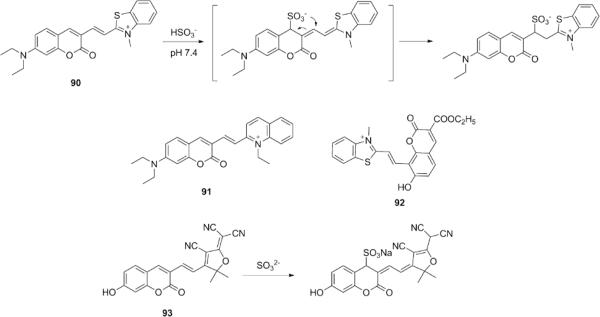

Guo's laboratory reported a colorimetric and ratiometric fluorescent probe 90 for HSO3− based on an addition-rearrangement cascade reaction (Fig. 23).184 In PBS buffers (10 mM, pH 7.4, containing 30% DMF), the reaction between 90 and HSO3− caused a gradual decrease in fluorescence intensity at 633 nm, accompanied by the formation of a new emission peak at 478 nm and a distinct color change from violet to colorless. These optical changes were attributed to nucleophilic addition of HSO3− to the C=C bond, interrupting the π-conjugation. The indicator did not respond to other RSS, including glutathione and H2S. It was applied to detect SO2 release in HeLa cells. Similar ratiometric probes (91-92) based on this approach were also reported,185,186 and more recent work by Yu and co-workers showed that the rearrangement step is dependent on the reaction media, as they observed that SO 2− 3addition occurs primarily to the coumarin ring of probe 93 in pure aqueous solutions (HEPES buffer, 20 mM, pH 7.4).187 Probe 93 is a water-soluble near-IR fluorescent probe with good selectivity for SO32− and a 0.27 nM detection limit.

Figure 23.

Structures of fluorescent probes for SO32−/HSO3− which undergo nucleophilic addition followed by rearrangement to give a turn-on response.

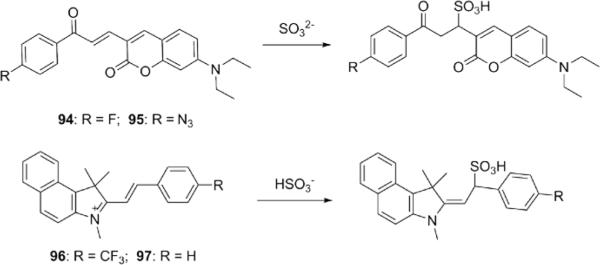

Finally, α,β-unsaturated systems have also been used in the design of SO32− probes (Fig. 24). For example, 1,4-addition of SO32− to 94 and 95 shortened π-conjugation of the probes, which induced a remarkable hypsochromic shift in maximal emission intensity. 188, 189 The reactions of HS− or GSH led to much less fluorescence enhancement for 94. As for 95, upon addition of HS−, the maximal emission intensity shifted from 590 nm to 564 nm, owing to the reduction of the azido group. However, after reaction with SO32−, the maximal emission intensity shifted from 590 nm to 460 nm. Therefore, 95 may be used to differentiate HS− and SO32−. Indicators 96 and 97 were developed using a similar reaction, but it was found that HS− could lead to obvious fluorescence enhancements.190,191

Figure 24.

Structures of fluorescent probes for SO32−/HSO3− incorporating α,β-unsaturated functionalities for reactivity.

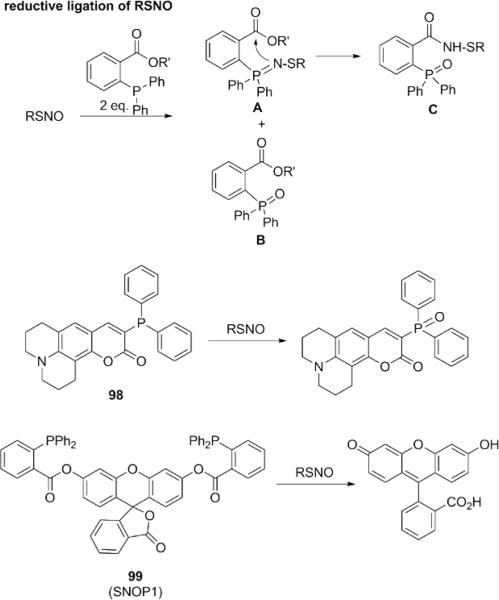

3.4. S-nitrosothiols

RSS also include modified cysteine derivatives, both in protein systems and small molecules such as glutathione. Important members in this category are sulfenic acids (RSOH), persulfides (RS-SH), and S-nitrosothiols (RSNO). These adducts are generated endogenously by corresponding reactive oxygen/nitrogen/sulfur species: H2O2, H2S, and NO, playing important roles in redox signaling as these modifications often regulate protein function.192 A number of detection methods for these species have been reported,192-195 most of which focus on labeling or enriching protein cysteine modifications (for identifying specific proteins or proteomics analysis). To date, specific fluorogenic probes for RSOH have not been reported. RSSH belongs to sulfane sulfur family so the probes for sulfane sulfurs, such as SSP2 (73), should also be useful for RSSH detection, although this has not yet been validated.

As for RSNO, two types of fluorescent probes (98, 99) have been reported (Fig. 25).196,197 In one strategy, it was found that RSNO can react with two equivalents of phosphines to form phosphine oxide A and thio-azaylide B. If an ester group is presented, A can further react with the ester to form sulfenamide product C. This reductive ligation of RSNO is mechanistically similar to the Staudinger ligation developed by Bertozzi's laboratory.198 Based on this reaction, Xian's laboratory reported an indictator based on RSNO mediated phosphine oxidation. Probe 98 is a triarylphosphine coumarin derivative where the phosphorus electron lone pair can quench the excited state of the coumarin fluorophore. Upon reaction with RSNO, oxidation of phosphine eliminates quenching effects and activates fluorescence. One drawback of this first-generation reagent is that other reactive oxidants such as H2O2 may also activate the probe. To solve this issue, Xian's group turned to a reductive ligation strategy, and the new reporter SNOP1 99 can rapidly react with RSNO to release free fluorescein and show strong fluorescence enhancement at 37 °C in Tris-HCl buffer (50 mM, pH = 7.4) containing 1% DMSO. This next-generation indicator showed good selectivity for various small molecule RSNOs, including S-nitrosoglutathione (GSNO), the predominant endogenous RSNO compound, but it is unclear if the probe can respond to protein SNO substrates. Notably, a variety of other RSS or ROS such as thiols, disulfides, H2S, H2O2, and HClO did not yield a fluorescence response. HNO also gives a high response, which is not surprising,199,200 but within biological contexts HNO is a very short-lived species compared to RSNO. Even if HNO coexists with RSNO in a given sample, HNO will likely decompose quickly (when its production is terminated) and not trigger false positives.

Figure 25.

Structures of probes for S-nitrosothiols.

4. Chemical probes for RSS-mediated post-translational modifications

S-Sulfhydration (forming –S-SH adducts from cysteine –SH residues) is a newly recognized oxidative post-translational modification caused by RSS,192 receiving growing attention in the context of H2S- and RSS-mediated signaling pathways. Although S-sulfhydration (also known as S-thiolation) is considered as an emerging mechanism in the field of redox biology, it has been long known that formation of protein persulfides (P-S-SH) can occur in biological systems and have been identified as intermediates in multiple biosynthetic pathways related to sulfur metabolism,143 such as in the production of sulfur-containing vitamins and other biomolecules.25,143 Interestingly, recent proteomics data showing that a relatively large number of proteins are the targets of S-sulfhydration suggest that this post-translational modification is a broad, general phenomenon that regulates the function of numerous systems within cells.26,201 Precise mechanisms that regulate S-sulfhydration are still under investigation, but it is clear that H2S cannot directly react with protein cysteine (-SH) to form persulfides without accompanying redox events and it is also unlikely that H2S reacts directly with protein disulfides to give sulfhydration, as H2S is a weak reductant compared to GSH.202,203 In contrast, H2S can plausibly convert some reactive S-oxidized forms such as sulfenic acids (SOH) or nitrosothiols (SNO) for S-sulfhydration, and protein cysteines (SH) may react with oxidized H2S derivatives, such as sulfane sulfurs or hydrogen polysulfides, to form persulfides. Indeed, recent work shows that polysulfides are much more potent than H2S in inducing sulfhydration in proteins such as Keap1, TRPA1 channels, roGFP2, and PTEN.147-149

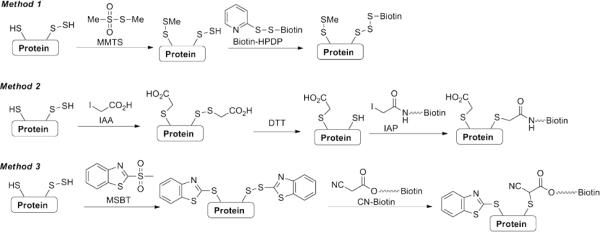

In this context, several methods have been reported for the detection of S-sulfhydration. Snyder and colleagues described a modified biotin switch technique (BST),22 which employs an alkylating agent S-methyl methanethiosulfonate (MMTS) to differentiate thiols and persulfides (Fig. 26). In this protocol, protein thiols (-SH) are first blocked by MMTS. Persulfides (-S-SH) are believed to remain unreacted and be available for subsequent conjugation to biotin-HPDP. Using this method, a large number of proteins were identified as targets for S-sulfhydration. However the underlying mechanism of selectivity of MMTS for thiol vs persulfide is unclear. Recent work by Carroll's laboratory has demonstrated that persulfides and thiols should have similar reactivities toward electrophiles such as MMTS.144 Tonks and co-workers reported a S-sulfhydration method where both –SH and –SSH can be blocked by alkylating reagents like iodoacetic acid (IAA), then the persulfide adducts (i.e. disulfides) can be reduced by DTT to form free –SH and subsequently labeled with iodoacetamide-linked biotin (IAP).23 The application of this method may be limited as DTT reduction should not be able to distinguish persulfide modifications from other DTT-reducible residues, such as normal protein disulfides, sulfenic acids, and S-nitrosothiols. Very recently a tag-switch method was reported as a selective method for protein S-sulfhydration. 204 This method requires two reagents to label protein persulfides in two-step reactions. The first step is to block –SH and -SSH by methylsulfonyl benzothiazole (MSBT). Like other thiol-blocking reagents, MSBT can effectively react with both groups to give –S-BT (benzothiazole) or –S-S-BT, respectively. These two adducts have very different reactivity towards nucleophiles. Protein-S-BT adducts are thioethers, which are unreactive to nucleophiles. In contrast, protein-S-S-BT are heterocycle-conjugated disulfides which are highly reactive to some carbon-based nucleophiles. When cyanoacetate-based reagents like CN-biotin are treated, stable thioether linkages will be formed. This tag-switch method appeared to be selective for protein persulfides and was used in identifying a number of S-sulfhydrated proteins in cell lysates.26,204

Figure 26.

Strategies for the detection of RSS-mediated post-translational modifications.

5. Concluding remarks

The emerging dynamic roles of H2S and related RSS in physiology and pathology have spurred the rapid development of chemical probes to detect and differentiate these species in living systems. These reagents, available in a growing spectrum of colors and featuring a variety of cellular and subcellular targeting functionalities, are developing technologies that will enable further exploration of RSS biology. In particular, key opportunities to focus on include the development of more sensitive probes that enable detection of endogenous levels of H2S. Ratiometric probes that will allow for semi-quantitative measurements are also a priority, as well as probes that can be used in live animal models, allowing for broader application of these chemical tools in biomedical research. Application of such emerging chemical technologies will help elucidate the mechanisms by which these reactive species modulate signaling pathways, maintain cellular function, and impact aging and disease states. In addition, trappable or targetable molecular and genetically-encoded probes offer the possibility to monitor RSS in individual cells to better understand the intracellular movement of these species, especially between different cell and tissue types. Furthermore, the interactions of RSS with other reactive species like nitric oxide, hydrogen peroxide, carbon monoxide, and higher order reactive nitrogen, oxygen, and carbon species may also provide insight into how such structurally simple molecules are able to elicit such a broad range of effects. This goal could be achieved using a combination of spectrally distinct chemoselective probes for dual imaging of synergistic species, such as H2S and NO. The continued development of new chemistry to be used at the frontier of this exciting area promises to identify sources and targets of RSS biology.

Acknowledgments

We thank the University of California, Berkeley, the Packard Foundation, the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (NIH GM 79465), as well as Amgen, Astra Zeneca, and Novartis for funding our work on redox imaging probes. C.J.C. is an Investigator with the Howard Hughes Medical Institute. M.X. thanks American Chemical Society (Teva USA Scholar Grant) and the NIH (R01HL116571).

References

- 1.Kimura H. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2014;20:783. doi: 10.1089/ars.2013.5309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mani S, Cao W, Wu L, Wang R. Nitric Oxide. 2014;41:62. doi: 10.1016/j.niox.2014.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Linden DR. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2014;20:818. doi: 10.1089/ars.2013.5312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fiorucci S, Distrutti E, Cirino G, Wallace JL. Gastroenterology. 2006;131:259. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.02.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Medani M, Collins D, Docherty NG, Baird AW, O'Connell PR, Winter DC. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2011;17:1620. doi: 10.1002/ibd.21528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ali MY, Whiteman M, Low CM, Moore PK. J. Endocrinol. 2007;195:105. doi: 10.1677/JOE-07-0184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Abe K, Kimura H. J. Neurosci. 1996;16:1066. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-03-01066.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yang G, Wu L, Jiang B, Yang W, Qi J, Cao K, Meng Q, Mustafa AK, Mu W, Zhang S, Snyder SH, Wang R. Science. 2008;322:587. doi: 10.1126/science.1162667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Elsey DJ, Fowkes RC, Baxter GF. Cell. Biochem. Funct. 2010;28:95. doi: 10.1002/cbf.1618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhao W, Zhang J, Lu Y, Wang R. EMBO J. 2001;20:6008. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.21.6008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Paul BD, Sbodio JI, Xu R, Vandiver MS, Cha JY, Snowman AM, Snyder SH. Nature. 2014;509:96. doi: 10.1038/nature13136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hu LF, Lu M, Tiong CX, Dawe GS, Hu G, Bian JS. Aging Cell. 2010;9:135. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2009.00543.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Giuliani D, Ottani A, Zaffe D, Galantucci M, Strinati F, Lodi R, Guarini S. Neurobiol. Learn. Mem. 2013;104:82. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2013.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nishida M, Sawa T, Kitajima N, Ono K, Inoue H, Ihara H, Motohashi H, Yamamoto M, Suematsu M, Kurose H, van der Vliet A, Freeman BA, Shibata T, Uchida K, Kumagai Y, Akaike T. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2012;8:714. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Francoleon NE, Carrington SJ, Fukuto JM. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2011;516:146. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2011.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hill BC, Woon TC, Nicholls P, Peterson J, Greenwood C, Thomson AJ. Biochem. J. 1984;224:59. doi: 10.1042/bj2240591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hartle MD, Sommer SK, Dietrich SR, Pluth MD. Inorg. Chem. 2014;53:7800. doi: 10.1021/ic500664c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kimura H, Nagai Y, Umemura K, Kimura Y. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2005;7:795. doi: 10.1089/ars.2005.7.795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li L, Rose P, Moore PK. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2011;51:169. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pharmtox-010510-100505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kabil O, Motl N, Banerjee R. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2014;1844:1355. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2014.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Paul BD, Snyder SH. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2012;13:499. doi: 10.1038/nrm3391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Peng Y-J, Nanduri J, Raghuraman G, Souvannakitti D, Gadalla MM, Kumar GK, Snyder SH, Prabhakar NR. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2010;107:10719. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1005866107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Krishnan N, Fu C, Pappin DJ, Tonks NK. Sci. Signal. 2011;4:ra86. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2002329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gadalla MM, Snyder SH. J. Neurochem. 2010;113:2010. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2010.06580.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mustafa AK, Gadalla MM, Sen N, Kim S, Mu W, Gazi SK, Barrow RK, Yang G, Wang R, Snyder SH. Sci. Signal. 2009;2:ra72. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2000464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ida T, Sawa T, Ihara H, Tsuchiya Y, Watanabe Y, Kumagai Y, Suematsu M, Motohashi H, Fujii S, Matsunaga T, Yamamoto M, Ono K, Devarie-Baez NO, Xian M, Fukuto JM, Akaike T. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2014;111:7606. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1321232111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shen X, Peter EA, Bir S, Wang R, Kevil CG. Free Rad. Biol. Med. 2012;52:2276. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2012.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chan J, Dodani SC, Chang CJ. Nat. Chem. 2012;4:973. doi: 10.1038/nchem.1500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kabil O, Banerjee R. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2014;20:770. doi: 10.1089/ars.2013.5339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Singh S, Banerjee R. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2011;1814:1518. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2011.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shibuya N, Tanaka M, Yoshida M, Ogasawara Y, Togawa T, Ishii K, Kimura H. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2009;11:703. doi: 10.1089/ars.2008.2253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Beard RS, Jr, Bearden SE. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2011;300:H13. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00598.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Watanabe M, Osada J, Aratani Y, Kluckman K, Reddick R, Malinow MR, Maeda N. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1995;92:1585. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.5.1585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vitvitsky V, Kabil O, Banerjee R. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2012;17:22. doi: 10.1089/ars.2011.4310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stein A, Bailey SM. Redox Biol. 2013;1:32. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2012.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dorman DC, Moulin FJ, McManus BE, Mahle KC, James RA, Struve MF. Toxicol. Sci. 2002;65:18. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/65.1.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Beauchamp RO, Jr, Bus JS, Popp JA, Boreiko CJ, Andjelkovich DA. Crit. Rev. Toxicol. 1984;13:25. doi: 10.3109/10408448409029321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Picton R, Eggo MC, Merrill GA, Langman MJ, Singh S. Gut. 2002;50:201. doi: 10.1136/gut.50.2.201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Carballal S, Trujillo M, Cuevasanta E, Bartesaghi S, Möller MN, Folkes LK, García-Bereguiaín MA, Gutiérrez-Merino C, Wardman P, Denicola A, Radi R, Alvarez B. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2011;50:196. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2010.10.705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Haouzi P, Klingerman CM. Respir. Physiol. Neurobiol. 2013;188:229. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2013.05.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Klingerman CM, Trushin N, Prokopczyk B. P. Haouzi. Am. J. Physiol. 2013;305:R630. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00218.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pietri R, Román-Morales E, López-Garriga J. Antioxid. Redox. Signal. 2011;15:393. doi: 10.1089/ars.2010.3698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Laggner H, Herman M, Esterbauer H, Muellner MK, Exner M, Gmeiner BM, Kapiotis S. J. Hypertens. 2007;25:2100. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e32829b8fd0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Montoya LA, Pearce TF, Hansen RJ, Zakharov LN, Pluth MD. J. Org. Chem. 2013;78:6550. doi: 10.1021/jo4008095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jarosz AP, Yep T, Mutus B. Anal. Chem. 2013;85:3638. doi: 10.1021/ac303543r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wintner EA, Deckwerth TL, Langston W, Bengtsson A, Leviten D, Hill P, Insko MA, Dumpit R, VandenEkart E, Toombs CF, Szabo C. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2010;160:941. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2010.00704.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fisher E. Chem. Ber. 1883;26:2234. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pandey SK, Kim K-H, Tang K-T. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2012;32:87. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ubuka T. J. Chromatogr. B Anal. Technol. Biomed. Life Sci. 2002;781:227. doi: 10.1016/s1570-0232(02)00623-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tangerman A. J. Chromatogr. B Anal. Technol. Biomed. Life Sci. 2009;877:3366. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2009.05.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hughes MN, Centelles MN, Moore KP. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2009;47:1346. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2009.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Peng B, Xian M. Asian J. Org. Chem. 2014;3:914. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yu F, Han X, Chen L. Chem. Commun. 2014;50:12234. doi: 10.1039/c4cc03312d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pluth MD, Bailey TS, Hammers MD, Montoya LA. Biochalcogen Chemistry: The Biological Chemistry of Sulfur, Selenium, and Tellurium. 2013:15. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lippert AR. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2014;133:136. doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2013.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Idoux JP. J. Chem. Soc. 1970;C:435. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Porter HK. Org. Reactions. 2011;20:455. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Nightingale D. Org. Synth. 1943;23:6. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Staudinger H, Freudenberger H. Org. Synth. 1931;11:94. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Grundmann C, Frommeld H-D. J. Org. Chem. 1966;31:157. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Park N, Heo Y, Kumar MR, Kim Y, Song KH, Lee S. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2012;10:1984. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Szabadváry F. Talanta. 1959;2:156. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kolthoff IM, Pearson EA. J. Phys. Chem. 1932;36:642. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Agard NJ, Baskin JM, Prescher JA, Lo A, Bertozzi CR. ACS Chem. Biol. 2006;1:644. doi: 10.1021/cb6003228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lippert AR, New EJ, Chang CJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:10078. doi: 10.1021/ja203661j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Peng H, Cheng Y, Dai C, King AL, Predmore BL, Lefer DJ, Wang BA. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2011;50:9672. doi: 10.1002/anie.201104236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wang K, Peng H, Ni N, Dai C, Wang B. J. Fluoresc. 2014;24:1. doi: 10.1007/s10895-013-1296-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Lin VS, Lippert AR, Chang CJ. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2013;110:7131. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1302193110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Zhang H, Wang P, Chen G, Cheung H-Y, Sun H. Tetrahedron Lett. 2013;54:4826. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Chen B, Li W, Lv C, Zhao M, Jin H, Jin H, Du J, Zhang L, Tang X. Analyst. 2013;138:946. doi: 10.1039/c2an36113b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Thorson MK, Majtan T, Kraus JP, Barrios AM. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2013;52:4641. doi: 10.1002/anie.201300841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Li W, Sun W, Yu X, Du L, Li M. J. Fluoresc. 2013;23:181. doi: 10.1007/s10895-012-1131-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Zhang J, Guo W. Chem. Commun. 2014;50:4214. doi: 10.1039/c3cc49605h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Zhou G, Wang H, Ma Y, Chen X. Tetrahedron. 2013;69:867. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Chen T, Zheng Y, Xu Z, Zhao M, Xu Y, Cui J. Tetrahedron Lett. 2013;54:2980. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Chen B, Lv C, Tang X. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2012;404:1919. doi: 10.1007/s00216-012-6292-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Saha T, Kanda D, Talukdar P. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2013;11:8166. doi: 10.1039/c3ob41884g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Zheng K, Lin W, Tan L. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2012;10:9683. doi: 10.1039/c2ob26956b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Montoya LA, Pluth MD. Chem. Commun. 2012;48:4767. doi: 10.1039/c2cc30730h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Qiao Q, Zhao M, Lang H, Mao D, Cui J, Xu Z. RSC Adv. 2014;4:25790. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Bailey TS, Pluth MD. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013;135:16697. doi: 10.1021/ja408909h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Zheng Y, Zhao M, Qiao Q, Liu H, Lang H, Xu Z. Dyes Pigments. 2013;98:367. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Sun W, Fan J, Hu C, Cao J, Zhang H, Xiong X, Wang J, Cui S, Suna S, Peng X. Chem. Commun. 2013;49:3890. doi: 10.1039/c3cc41244j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Das SK, Lim CS, Yang SY, Han J, Cho BR. Chem. Commun. 2012;48:8395. doi: 10.1039/c2cc33909a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Cai Y, Li L, Wang Z, Sun JZ, Qin A, Tang BZ. Chem. Commun. 2014;50:8892. doi: 10.1039/c4cc02844a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Chen S, Chen Z-J, Ren W, Ai H-W. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012;134:9589. doi: 10.1021/ja303261d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Chen Z-J, Ai H-W. Biochemistry. 2014;53:5966. doi: 10.1021/bi500830d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Yu F, Li P, Song P, Wang B, Zhao J, Han K. Chem. Commun. 2012;48:2852. doi: 10.1039/c2cc17658k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Wan Q, Song Y, Li Z, Gao X, Ma H. Chem. Commun. 2013;49:502. doi: 10.1039/c2cc37725j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Yu C, Li X, Zeng F, Zheng F, Wu S. Chem. Commun. 2013;49:403. doi: 10.1039/c2cc37329g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Wu Z, Li Z, Yang L, Han J, Han S. Chem. Commun. 2012;48:10120. doi: 10.1039/c2cc34682f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Erez R, Shabat D. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2008;6:2669. doi: 10.1039/b808198k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Bae SK, Heo CH, Choi DJ, Sen D, Joe E-H, Cho BR, Kim HMA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013;135:9915. doi: 10.1021/ja404004v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Jiang Y, Wu Q, Chang X. Talanta. 2014;121:122. doi: 10.1016/j.talanta.2014.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Chen B, Wang P, Jin Q, Tang X. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2014;12:5629. doi: 10.1039/c4ob00923a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Robbins JS, Schmid KM, Phillips ST. J. Org. Chem. 2013;78:3159. doi: 10.1021/jo400105m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Zhang L, Li S, Hong M, Xu Y, Wang S, Liu Y, Qian Y, Zhao J. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2014;12:5115. doi: 10.1039/c4ob00285g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Liu X-L, Du X-J, Dai C-G, Song Q-H. J. Org. Chem. 2014;79:9481. doi: 10.1021/jo5014838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Wang P, Song Y, Zhang L, He H, Zhou X. Curr. Med. Chem. 2005;24:2893. doi: 10.2174/092986705774454724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Wang R, Yu F, Chen L, Chen H, Wang L, Zhang W. Chem. Commun. 2012;48:11757. doi: 10.1039/c2cc36088h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Wu M-Y, Li K, Hou J-T, Huang Z, Yu X-Q. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2012;10:8342. doi: 10.1039/c2ob26235e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Zhang L, Meng WG, Lu L, Xue YS, Li C, Zou F, Liu Y, Zhao J. Sci. Rep. 2014;29:5870. doi: 10.1038/srep05870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Cui L, Zhong Y, Zhu W, Xu Y, Du Q, Wang X, Qian X, Xiao Y. Org. Lett. 2011;13:928. doi: 10.1021/ol102975t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Cenas N, Prast S, Nivinskas H, Sarlauskas J, Arnér ES. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:5593. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M511972200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Fridkin M, Hazum E, Tauber-Finkelstein M, Shaltiel S. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1977;178:517. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(77)90222-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Philosof-Oppenheimer R, Pecht I, Fridkin M. Int. J. Peptide Protein Res. 1995;45:116. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3011.1995.tb01029.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Liu T, Zhang X, Qiao Q, Zou C, Feng L, Cui J, Xu Z. Dyes Pigments. 2013;99:537. [Google Scholar]

- 108.Liu H-Y, Zhao M, Qiao Q-L, Lang H-J, Xu J-Z, Xu Z-C. Chinese Chem. Lett. 2014;25:1060. [Google Scholar]

- 109.Yuan L, Zuo Q-P. Sensor Actuat. B-Chem. 196:151. [Google Scholar]

- 110.Tang C, Zheng Q, Zong S, Wang Z, Cui Y. Sensor Actuat. B-Chem. 2014;202:99. [Google Scholar]

- 111.Cao X, Lin W, Zheng K, He L. Chem. Commun. 2012;48:10529. doi: 10.1039/c2cc34031c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Turan IS, Sozmen F. Sensor Actuat. B-Chem. 2014;201:13. [Google Scholar]

- 113.Maity D, Raj A, Samanta PK, Karthigeyan D, Kundu TK, Patib SK, Govindaraju T. RSC Adv. 2014;4:11147. [Google Scholar]

- 114.Yuan L, Zuo Q-P. Chem. Asian J. 2014;9:1544. doi: 10.1002/asia.201400131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Liu T, Xu Z, Spring DR, Cui J. Org. Lett. 2013;15:2310. doi: 10.1021/ol400973v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Liu Y, Feng G. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2014;12:438. doi: 10.1039/c3ob42052c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Huang Z, Ding S, Yu D, Huang F, Feng G. Chem. Commun. 2014;50:9185. doi: 10.1039/c4cc03818e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Wei C, Wei L, Xi Z, Yi L. Tetrahedron Lett. 2013;54:6937. [Google Scholar]

- 119.Hammers MD, Pluth MD. Anal. Chem. 2014;86:7135. doi: 10.1021/ac501680d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Chen Y, Zhu C, Yang Z, Chen J, He Y, Jiao Y, He W, Qiu L, Cen J, Guo Z. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2013;52:1688. doi: 10.1002/anie.201207701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Liu J, Sun Y-Q, Zhang J, Yang T, Cao J, Zhang L, Guo W. Chem. Eur. J. 2013;19:4717. doi: 10.1002/chem.201300455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Long L, Zhou L, Wang L, Meng S, Gong A, Du F, Zhang C. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2013;11:8214. doi: 10.1039/c3ob41741g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Peng H, Chen W, Cheng Y, Hakuna L, Strongin R, Wang B. Sensors. 2012;12:15907. doi: 10.3390/s121115907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Smithies O. Science. 1965;150:1595. doi: 10.1126/science.150.3703.1595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Söderdahl T, Enoksson M, Lundberg M, Holmgren A, Ottersen OP, Orrenius S, Bolcsfoldi G, Cotgreave IA. FASEB J. 2003;17:124. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-0259fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Liu C, Pan J, Li S, Zhao Y, Wu LY, Berkman CE, Whorton AR, Xian M. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2011;50:10327. doi: 10.1002/anie.201104305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Peng B, Chen W, Liu C, Rosser EW, Pacheco A, Zhao Y, Aguilar HC, Xian M. Chem.–Eur. J. 2014;20:1010. doi: 10.1002/chem.201303757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Xu Z, Xu L, Zhou J, Xu Y, Zhu W, Qian X. Chem. Commun. 2012;48:10871. doi: 10.1039/c2cc36141h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Qian Y, Karpus J, Kabil O, Zhang S-Y, Zhu H-L, Banerjee R, Zhao J, He C. Nat. Commun. 2011:2–495. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1506. DOI: 10.1038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Li X, Zhang S, Cao J, Xie N, Liu T, Yang B, He Q, Hu Y. Chem. Commun. 2013;49:8656. doi: 10.1039/c3cc44539a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Qian Y, Yang B, Shen Y, Du Q, Lin L, Lin J, Zhu H. Sensor Actuat. B-Chem. 2013;182:498. [Google Scholar]

- 132.Liu C, Peng B, Li S, Park C-M, Whorton AR, Xian M. Org. Lett. 2012;14:2184. doi: 10.1021/ol3008183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Wang X, Sun J, Zhang W, Ma X, Lv J, Tang B. Chem. Sci. 2013;4:2551. [Google Scholar]

- 134.Choi MG, Cha S, Lee H, Jeon HL, Chang S-K. Chem. Commun. 2009:7390. doi: 10.1039/b916476f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Sasakura K, Hanaoka K, Shibuya N, Mikami Y, Kimura Y, Komatsu T, Ueno T, Terai T, Kimura H, Nagano T. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:18003. doi: 10.1021/ja207851s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Hou F, Huang L, Xi P, Cheng J, Zhao X, Xie G, Shi Y, Cheng F, Yao X, Bai D, Zeng Z. Inorg. Chem. 2012;51:2454. doi: 10.1021/ic2024082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Hou F, Cheng J, Xi P, Chen F, Huang L, Xie G, Shi Y, Liu H, Bai D, Zeng Z. Dalton Trans. 2012;41:5799. doi: 10.1039/c2dt12462a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Santos-Figueroa LE, de la Torre C, El Sayed S, Sancenón F, Martínez-Máñez R, Costero AM, Gil S, Parra M. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2014;2014:41. [Google Scholar]

- 139.Qu X, Li C, Chen H, Mack J, Guo Z, Shen Z. Chem. Commun. 2013;49:7510. doi: 10.1039/c3cc44128h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Jacob C, Anwar A, Burkholz T. Planta Med. 2008;74:1580. doi: 10.1055/s-0028-1088299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Toohey JI. Biochem. J. 1989;264:625. doi: 10.1042/bj2640625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Westley AM, Westley J. Anal. Biochem. 1991;195:63. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(91)90295-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Mueller EG. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2006;2:185. doi: 10.1038/nchembio779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Pan J, Carroll K. ACS Chem. Biol. 2013;8:1110. doi: 10.1021/cb4001052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Toohey JI. Anal. Biochem. 2011;413:1. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2011.01.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Jacob C, Anwar A, Burkholz T. Planta Med. 2008;74:1580. doi: 10.1055/s-0028-1088299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Kimura Y, Mikami Y, Osumi K, Tsugane M, Oka JI, Kimura H. FASEB J. 2013;27:2451. doi: 10.1096/fj.12-226415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Koike S, Ogasawara Y, Shibuya N, Kimura H, Ishii K. FEBS Lett. 2013;587:3548. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2013.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Greiner R, Pálinkás Z, Bäsell K, Becher D, Antelmann H, Nagy P, Dick TP. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2013;19:1749. doi: 10.1089/ars.2012.5041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Wood JL. Methods Enzymol. 1987;143:25. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(87)43009-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.Chen W, Liu C, Peng B, Zhao Y, Pacheco A, Xian M. Chem. Sci. 2013;4:2892. doi: 10.1039/C3SC50754H. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152.Liu C, Chen W, Shi W, Peng B, Zhao Y, Ma H, Xian M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014;136:7257. doi: 10.1021/ja502968x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153.Griffith OW. Methods Enzymol. 1987;143:366. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(87)43065-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 154.Stipanuk MH. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 2004;24:539. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nutr.24.012003.132418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 155.Kimura H. Exp. Physiol. 2011;96:833. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2011.057455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 156.Liu D, Huang Y, Bu D, Liu AD, Holmberg L, Jia Y, Tang C, Du J, Jin H. Cell Death Dis. 2014;5:e1251. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2014.229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 157.Meng Z, Zhang H. Inhal. Toxicol. 2007;19:979. doi: 10.1080/08958370701515175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 158.Du S, Jin H, Bu D, Zhao X, Geng B, Tang C, Du J. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2008;29:923. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7254.2008.00845.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 159.Meng Z, Geng H, Bai J, Yan G. Inhal. Toxicol. 2003;15:951. doi: 10.1080/08958370390215785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 160.Wang X, Jin H, Tang C. J. Du. Clin. Exp. Pharmacol. Physiol. 2010;37:745. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.2009.05249.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 161.Meng Z, Li J. Acta Physiol. Sin. 2011;63:593. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 162.Townsend TM, Allanic A, Noonan C, Sodeau JR. J. Phys. Chem. A. 2012;116:4035. doi: 10.1021/jp212120h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 163.Li J, Meng Z. Nitric Oxide. 2009;20:166. doi: 10.1016/j.niox.2008.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 164.Meng Z, Li J, Zhang Q, Bai W, Yang Z, Zhao Y, Wang F. Inhal. Toxicol. 2009;21:1223. doi: 10.3109/08958370902798463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 165.Choi MG, Hwang J, Eor S, Chang S. Org. Lett. 2010;12:5624. doi: 10.1021/ol102298b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 166.Gu X, Liu C, Zhu YC, Zhu YZ. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2011;59:11935. doi: 10.1021/jf2032928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 167.Liu C, Wu H, Yang W, Zhang X. Anal. Sci. 2014;30:589. doi: 10.2116/analsci.30.589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 168.Chen S, Hou P, Wang J, Song X. RSC Adv. 2012;2:10869. [Google Scholar]

- 169.Ma X, liu C, Shan Q, Wei G, Wei D, Du Y. Sens. Actuators, B. 2013;188:1196. [Google Scholar]

- 170.Paritala H, Carroll KS. Anal. Biochem. 2013;440:32. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2013.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 171.Wang G, Qi H, Yang X. Luminescence. 2013;28:97. doi: 10.1002/bio.2344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 172.Cheng X, Jia H, Feng J, Qin J, Li Z. Sens. Actuators, B. 2013;184:274. [Google Scholar]

- 173.Cheng X, Jia H, Feng J, Qin J, Li Z. J. Mater. Chem. B. 2013;1:4110. doi: 10.1039/c3tb20159g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 174.Yu C, Luo M, Zeng F, Wu S. Anal. Methods. 2012;4:2638. [Google Scholar]

- 175.Xie H, Zeng F, Yu C, Wu S. Polym. Chem. 2013;4:5416. [Google Scholar]

- 176.Yang X, Zhao M, Wang G. Sens. Actuators, B. 2011;152:8. [Google Scholar]

- 177.Sun Y, Wang P, Liu J, Zhang J, Guo W. Analyst. 2012;137:3430. doi: 10.1039/c2an35512d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 178.Lin W, Long L, Yuan L, Cao Z, Chen B, Tan W. Org. Lett. 2008;10:5577. doi: 10.1021/ol802436j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 179.Kim T, Lee D, Kim H. Tetrahedron Lett. 2008;49:4879. [Google Scholar]

- 180.Cai X, Li J, Zhang Z, Wang G, Song X, You J, Chen L. Talanta. 2014;120:297–303. doi: 10.1016/j.talanta.2013.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 181.Wang P, Liu J, Lv X, Liu Y, Zhao Y, Guo W. Org. Lett. 2012;14:520. doi: 10.1021/ol203123t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 182.Li G, Chen Y, Wang J, Lin Q, Zhao J, Ji L, Chao H. Chem. Sci. 2013;4:4426. [Google Scholar]

- 183.Santos-Figueroa LE, Giménez C, Agostini A, Aznar E, Marcos MD, Sancenón F, Martínez-Máñez R, Amorós P. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2013;52:13712. doi: 10.1002/anie.201306688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 184.Sun Y, Liu J, Zhang J, Yang T, Guo W. Chem. Commun. 2013;49:2637. doi: 10.1039/c3cc39161b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 185.Tan L, Lin W, Zhu S, Yuan L, Zheng K. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2014;12:4637. doi: 10.1039/c4ob00132j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 186.Peng M, Yang X, Yin B, Guo Y, Suzenet F, En D, Li J, Li C, Duan Y. Chem. Asian J. 2014;9:1817. doi: 10.1002/asia.201402113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 187.Wu M, Li K, Li C, Hou J, Yu X. Chem. Commun. 2014;50:183. doi: 10.1039/c3cc46468g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 188.Tian H, Qian J, Sun Q, Bai H, Zhang W. Anal. Chim. Acta. 2013;788:165. doi: 10.1016/j.aca.2013.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 189.Tian H, Qian J, Sun Q, Jiang C, Zhang R, Zhang W. Analyst. 2014;139:3373. doi: 10.1039/c4an00478g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 190.Sun Y, Zhao D, Fan S, Duan L, Li R. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2014;62:3405. doi: 10.1021/jf5004539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 191.Sun Y, Fan S, Zhang S, Zhao D, Duan L, Li R. Sens. Actuators, B. 2014;193:173. [Google Scholar]

- 192.Paulsen CE, Carroll KS. Chem. Rev. 2013;113:4633. doi: 10.1021/cr300163e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 193.Wang H, Xian M. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2011;15:32. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2010.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 194.Devarie-Baez NO, Zhang D, Li S, Whorton AR, Xian M. Methods. 2013;62:171. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2013.04.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 195.Bechtold E, King SB. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2012;17:981. doi: 10.1089/ars.2012.4570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 196.Pan J, Downing JA, McHale JL, Xian M. Mol. BioSyst. 2009;5:918. doi: 10.1039/b822283e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 197.Zhang D, Chen W, Miao Z, Ye Y, Zhao Y, King SB, Xian M. Chem. Commun. 2014;50:4806. doi: 10.1039/c4cc01288g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 198.Saxon E, Bertozzi CR. Science. 2000;287:2007. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5460.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]