Abstract

Long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) are emerging as major regulators of cellular phenotypes and implicated as oncogenes or tumor suppressors. Here we report a novel tumor suppressive locus on human chromosome 15q23 that contains two multi-exonic lncRNA genes of 100 kb each: DRAIC (LOC145837) and the recently reported PCAT29. The DRAIC lncRNA was identified from RNA-seq data and is downregulated as prostate cancer cells progress from an androgen dependent (AD) to castration resistant (CR) state. Prostate cancers persisting in patients after androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) select for decreased DRAIC expression, and higher levels of DRAIC in prostate cancer is associated with longer disease-free survival (DFS). Androgen induced androgen receptor (AR) binding to the DRAIC locus and repressed DRAIC expression. In contrast, FOXA1 and NKX3-1 are recruited to the DRAIC locus to induce DRAIC, and FOXA1 specifically counters the repression of DRAIC by AR. The decrease of FOXA1 and NKX3-1, and aberrant activation of AR, thus accounts for the decrease of DRAIC during prostate cancer progression to the CR state. Consistent with DRAIC being a good prognostic marker, DRAIC prevents the transformation of cuboidal epithelial cells to fibroblast-like morphology and prevents cellular migration and invasion. A second tumor suppressive lncRNA PCAT29, located 20 kb downstream of DRAIC, is regulated identically by AR and FOXA1 and also suppresses cellular migration and metastasis. Finally, based on TCGA analysis, DRAIC expression predicts good prognosis in a wide range of malignancies: bladder cancer, low grade gliomas, lung adenocarcinoma, stomach adenocarcinoma, renal clear cell carcinoma, hepatocellular carcinoma, skin melanoma and stomach adenocarcinoma.

Implications

This study reveals a novel tumor suppressive locus encoding two hormone-regulated lncRNAs, DRAIC and PCAT29, that are prognostic for a wide variety of cancer types.

Keywords: prostate cancer, castration resistance, lncRNA, androgen receptor

Introduction

The growth of prostate cancer cells initially depends on androgen. Therefore, Androgen Deprivation Therapy (ADT) is useful for primary prostate cancer. However, prostate cancer cells progress after ADT to grow in low androgen, a condition called castration resistant (CR) (formerly androgen-independent) state, leading to a tumor recurrence and metastasis (1). Several lines of evidence have shown that the Androgen Receptor (AR) or androgen-responsive pathways are differently activated in the CR cells so that pathways are active in low or absent androgen (1,2) . In addition, alternative pathways such as mTOR and IGF1R signaling are activated to mimic the action of androgens and promote prostate cancer cell growth (3). However, the detailed mechanisms by which androgen dependent (AD) cells become CR remain unclear.

Recent transcriptome analyses have identified a variety of non-coding RNAs as important gene regulators (4–9). Long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) are defined as RNAs >200 nt in length with no functional open reading frame (10). Our lab has identified two novel lncRNAs, APTR (Alu-mediated p21 transcriptional regulator), which recruits PRC2 (Polycomb repressive complex 2) to p21 promoter region to repress the transcription of p21 (4) and MUNC (MyoD Upstream Non-Coding), which can promote myogenesis (6). Some lncRNAs are known to be aberrantly expressed and act as oncogenes or tumor suppressors in cancers including prostate cancer. Nuclear lncRNAs, PCGEM1 and PRNCR1 bind to AR to stimulate AR-mediated gene programs (11). Cytoplasmic lncRNA, PCAT-1 suppresses BRCA2 through its 3′UTR (untranslated region) to control homologous recombination (12). But how these prostate cancer related lncRNAs are regulated or whether they contribute to prostate cancer progression is largely unknown (11–13).

In our previous work, we performed microRNA (miRNA) screening using AD and CR cells and identified a tumor suppressive miRNA, miR-99a, that is downregulated in CR cells and repressed by AR (14,15). We also showed that multiple oncogenes, mTOR, SMARCD1, SNF2H and IGF1R targeted by miR-99a contribute to prostate cancer progression (14–16). In this study, we report a novel lncRNA designated as DRAIC (Downregulated RNA in Androgen Independent Cells) that is similarly regulated. AR is recruited to DRAIC locus to repress DRAIC. Conversely, DRAIC is induced by FOXA1 and NKX3-1, which are recruited to the same region as AR at the DRAIC locus and FOXA1 counters the repression of DRAIC by AR. Interestingly, a tumor suppressive lncRNA, PCAT29, which was recently reported by Malik et.al. (13), is located 20kb downstream of DRAIC locus and we report that it is also regulated by AR, FOXA1 and NKX3-1 just like DRAIC. Functional analyses show that DRAIC inhibits cancer cell migration and invasion. This study indicates that progression of prostate cancer is accompanied by a decrease of FOXA1 and NKX3-1, which leads to the decrease both the novel tumor suppressive lncRNAs, DRAIC and PCAT29, thereby increasing prostate cancer migration and invasion and decreasing disease free survival. This is the first report of a novel lncRNA cluster, DRAIC/PCAT29 regulated by the same mechanism and suppressing prostate cancer progression. Analysis of publicly available data from TCGA (The Cancer Genome Atlas) revealed that DRAIC is a predictor of good prognosis in at least seven other malignancies.

Materials and Methods

Cell culture

VCap cells were maintained in DMEM. PC3M-luc cells were maintained in MEM-L glutamine containing MEM Non-Essential Amino Acids, MEM Vitamin Solution, Sodium Pyruvate (All are Life technology.). Other cells were maintained in RPMI1640 medium. All medium contain 10% fetal calf serum, except when measuring the effect of androgen. For the experiments on androgen responsiveness, LNCaP cells were cultured in phenol red–free RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with charcoal:dextran-stripped FBS (Hyclone) for 48 hours before the addition of R1881 (Perkin-Elmer).

Transfection

Transfections of siRNA (50nM) and plasmid vector were performed with Lipofectamine RNAiMax and Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen), respectively. siRNA sequences are shown in Supplementary Table1.

Scratch wound healing assay

Scratches were performed by pipet tip in 6 well plate. After incubation for 24h or 48h, the migration of cells into the scratch was imaged. Gap areas were calculated by Image J.

Matrigel invasion assay

Cells were seeded into 24 well Matrigel Invasion Chamber (BD Biosciences) at 1×105 cells in serum free medium. 10% FCS as chemoattractant was added only to the lower compartment. After incubation for 48h, the non-invaded cells were removed from the upper surface of the membrane by a cotton swab. The invaded cells were fixed using methanol, stained by Crystal Violet and counted per membrane.

RNA isolation, RT-PCR, Western Blotting and ChIP assay

Total RNA and nuclear/cytoplasmic RNAs were extracted using Trizol total RNA isolation reagent (Invitrogen), PARIS kit (Ambion), respectively. RT-PCR and Western Blotting were performed according to standard protocols. ChIP assay was performed with cells crosslinked with 1% formaldehyde and using 5 ug of antibody on Dynabeads according to published protocol (4). All details of the protocols are in Supplementary Information.

ChIP-seq analysis and RNA-seq analysis

Publicly available ChIP-seq and RNA-seq data were downloaded and analyzed by standard bioinformatics protocols. Details are described in Supplementary Information.

Kaplan-Meier plot analysis

Publicly available TCGA data at cBioPortal (17) was used to plot Kaplan-Meier plots on tumors divided into two groups based on level of DRAIC expressed as a Z-score (18–20) Only those plots are included that showed a statistically significant (p<0.05) survival difference between the two groups of patients. Similar trends were seen in other plots of these malignancies but are not included because the p-value did not reach significance.

Results

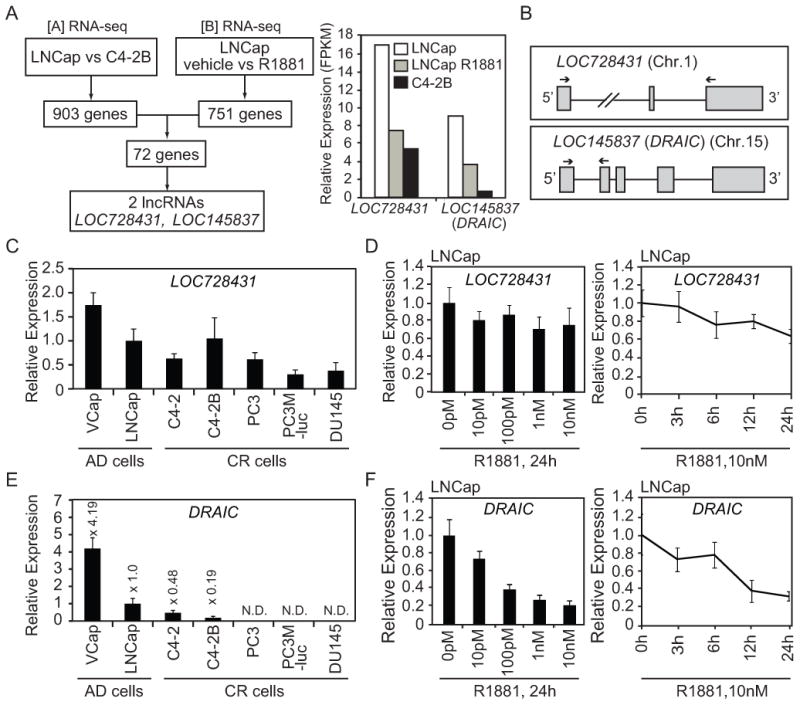

DRAIC is a novel lncRNA decreased in CR cells and repressed by R1881

In order to identify novel lncRNAs involved in prostate cancer progression, we compared two published RNA-sequencing (RNA-seq) datasets (21,22), [A] LNCap vs C4-2B cells and [B] vehicle vs R1881 (androgen analog)-treated LNCap cells (Fig.1A). C4-2B cells are bone metastatic CR cells derived from parental AD, LNCap cells (23). We tried to identify the lncRNAs that are (a) increased in C4-2B compared to LNCaP cells and induced by R1881 in LNCap cells or (b) decreased in C4-2B compared to LNCaP cells and repressed by R1881 in LNCap cells.

Figure 1. LncRNA, DRAIC is downregulated in CR cells and decreased by R188.

(A) Left: analysis of published RNA-seq datasets. Right: Relative expression (FPKM: Fragments Per Kilobase of exon per Million fragments mapped) of LOC728431 and LOC145837 (DRAIC) in LNCap cells treated with vehicle or R1881 and C4-2B cells treated with vehicle (B) Top and bottom show LOC728431 and LOC145837 (DRAIC) gene structures and qPCR primer locations, respectively. (C) The expression of LOC728431 in a panel of prostate cancer cells cultured in the growth medium was measured by RT-qPCR and normalized to GAPDH. Mean±S.D. n=3. The expression in LNCap is set as 1. (D) LNCap cells were treated with R1881 at different doses (left) and times (right) and the expression of LOC728431 was measured by RT-qPCR. The expression in 0 pM or 0 h is set as 1. Rest as in Fig. 1C. (E) The expression of DRAIC in a panel of prostate cancer cells cultured in growth medium was measured by RT-qPCR. Rest as in Fig. 1C. (F) LNCap cells were treated with R1881 at different doses (left) and times (right) and the expression of DRAIC was measured by RT-qPCR. Rest as in Fig. 1C, D.

903 and 751 genes were differentially expressed (p<0.05) in [A] and [B] comparisons, respectively (Fig.1A). Intersection of these genes identified 72 genes that meet (a) or (b) criteria as mentioned above. Among them, there were two lncRNAs, LOC728431 (also known as LINC01137) and LOC145837. Both were lower in C4-2B than LNCap cells and repressed by R1881 in LNCap cells (Fig.1A). LOC728431 and LOC145837 are composed of 3 exons at Chr.1p34.3 and 5 exons at Chr.15q23, respectively (Fig.1B).

Q-RT-PCR showed that LOC728431 is almost at the same level in LNCap and C4-2B cells and is not drastically decreased by R1881, contrary to the RNA-seq comparisons (Fig.1C, D). Therefore we excluded LOC728431 from further analysis.

In contrast, Q-RT-PCR confirmed that C4-2B cells express lower level of LOC145837 (renamed by us as DRAIC) than LNCap cells and the expression is also decreased in other CR cells (Fig. 1E). In addition, DRAIC was repressed by R1881 in dose and time-dependent manners (Fig. 1F).

DRAIC is a cytoplasmic and poly-adenylated RNA

DRAIC is a spliced transcript of 1.7 kb that is expressed mainly in the cytoplasm (Supplementary Fig.1A). The coding potential (calculated by CPAT, http://rna-cpat.sourceforge.net/) of DRAIC is 0.342, which is comparable with those of other cytoplasmic lncRNAs: PCAT1 (12) (0.693) (2.1 kb RNA) and TINCR (24) (0.204) (3.8 kb RNA). For comparison, the coding potential of protein coding genes like GAPDH and Orc1 are 0.99. We confirmed the 3′end of DRAIC by 3′RACE using LNCap polyA+ RNA (Supplementary Fig. 1B). There are at least 3 additional transcript variants of DRAIC (Supplementary Fig. 2A) although RNA-seq data in LNCap cells (vehicle) (21) shows that the read counts of these 3 additional variants are much less than the ones of DRAIC (data not shown). Q-RT-PCR with variant-specific primers revealed that their expression patterns are similar to DRAIC (Supplementary Fig. 2B). There is no evidence in the 3′RACE-PCR products, the EST database or the RNAseq data of DRAIC being spliced to the PCAT29 gene (13) that is located 20 kb downstream.

DRAIC is a clinically relevant lncRNA in a variety of cancers

In order to test whether Androgen Deprivation Therapy (ADT) selects for changes in expression of DRAIC as the cancer progresses to CR state, we analyzed published RNA-seq of seven prostate cancer rich tumor biopsies before and after 22 weeks of ADT (25). Prostate cancer that persisted after ADT shows a 10X decrease of DRAIC (Fig. 2A), suggesting that androgen deprivation in patients selects for cancer cells with low expression of DRAIC. Note that the original publication (25) shows that only about 1600 genes are increased or decreased >2x by ADT with the vast majority of genes remaining unchanged, suggesting that the decrease of DRAIC was not due to a change in the lineage of cells surviving ADT.

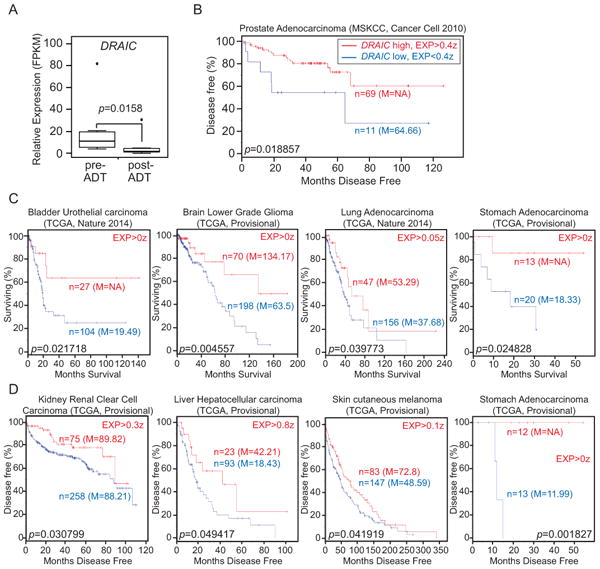

Figure 2. DRAIC is a clinically relevant lncRNA.

(A) Relative expression (FPKM) of DRAIC in prostate cancer pre- and post-ADT (Androgen Deprivation Therapy) (post-ADT: prostate cancer harvested approximately 22 weeks after ADT initiation) using published RNA-seq dataset from 7 patients (25). The expression of DRAIC was determined using the Tuxedo suite and plotted using R. The statistical significance of the changes in DRAIC expression was evaluated using a paired t-test. p=0.0158. (B). Kaplan–Meier plot of disease-free survival (DFS) of patient with prostate adenocarcinoma from the MSKCC dataset (18) stratified by level of DRAIC expression. In Log rank test p=0.018857. High: DRAIC level > +0.4z and Low: DRAIC level < +0.4z. (C and D) Kaplan–Meier plot of Overall survival (OS) (C) or Disease Free Survival (D) for indicated malignancies from TCGA (19,20) stratified by level of DRAIC expression. EXP: the DRAIC expression level z-score cut-off used for dividing high expressers from low expressers. n = number of patients in that group, M = median survival in months of that group. NA: not available.

If decreased DRAIC is a marker for progression of prostate cancer to CR state, one would predict that high levels of DRAIC may predict a good prognosis. Kaplan-Meier plot based on RNAseq and disease progression data from “Prostate Adenocarcinoma (MSKCC, 2010)” available at cBioPortal (18) revealed that lower expression of DRAIC predicts a lower probability of disease-free-survival of patients (Fig. 2B). Thus, DRAIC is a clinically relevant lncRNA that favors a good response to therapy of prostate cancer.

We wondered whether the good prognostic function of DRAIC could be extended to an unrelated malignancy. Kaplan-Meier plots were calculated using RNAseq and overall survival or disease-free survival data for the tumors indicated in Fig. 2C, D. Seven malignancies showed statistically significant survival benefit of DRAIC overeexpression in either overall survival (bladder cancer, lower grade glioma, lung adnocarcinoma) or disease free survival (renal clear cell carcinoma, hepatocellular carcinoma, skin melanoma) or both (stomach adenocarcinoma).

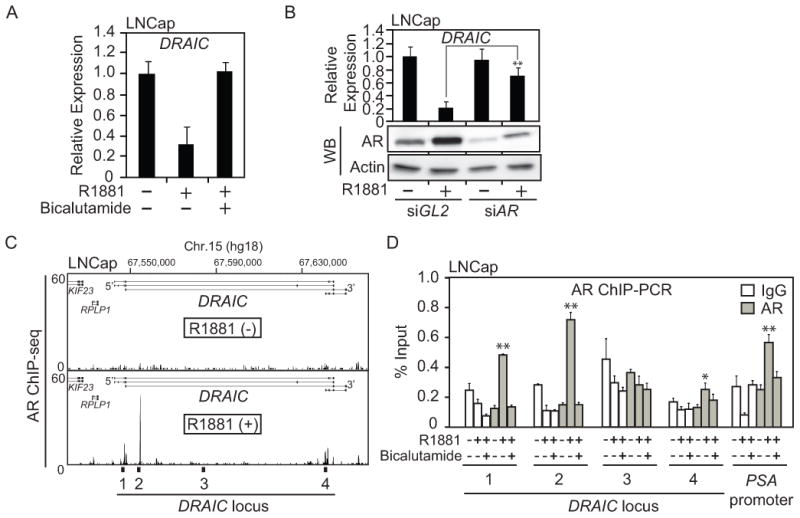

AR is recruited to DRAIC promoter and required for the repression of DRAIC

We next sought to identify how DRAIC is repressed by Androgen. The downregulation of DRAIC by the androgen analog, R1881, was reversed by androgen antagonist, Bicalutamide and by AR knockdown (Fig. 3A, B). We analyzed published AR Chromatin Immunoprecipitation-sequencing (ChIP-seq) data (26) and identified several sites upstream and within DRAIC that are bound by AR in the presence of R1881 (Fig. 3C). AR ChIP-PCR confirmed that AR is recruited to Regions 1, 2 and 4 by R1881 (second grey bar in each set) and that the recruitment is diminished by Bicalutamide (third grey bar in each set) (Fig. 3D). Therefore, androgen-driven AR recruitment to the DRAIC locus is associated with the repression.

Figure 3. AR is recruited to DRAIC locus and required for DRAIC downregulation.

(A) LNCaP cells were treated with no androgen, 10 nM R1881, 10 nM R1881 plus 10 uM Bicalutamide for 24h. The expression of DRAIC in LNCaP cells was measured by RT-qPCR and normalized to GAPDH. Rest as in Fig. 1C. (B) The expression of DRAIC in LNCaP cells after knocking down AR by siRNA for 72 h in the absence or presence of 10 nM R1881 for 24h. ** indicates p-value of difference from siGL2 < 0.01. Rest as in Figure 1C. The expression of AR and Actin (loading control) were detected by western blotting. (C) Published AR ChIP-seq (26) peaks in LNCap cells at DRAIC locus in the absence (upper) or presence (lower) of R1881. Regions 1-4 in the DRAIC locus are marked. (D) LNCap cells were treated with or without 10 nM R1881 and 10uM Bicalutamide for 24h and AR ChIP-PCR performed. PSA promoter was used as a positive control (15) and region 3 was used as a negative control. The value was expressed as percentage of input DNA. ** and * indicate p-value <0.01, 0.05, respectively.

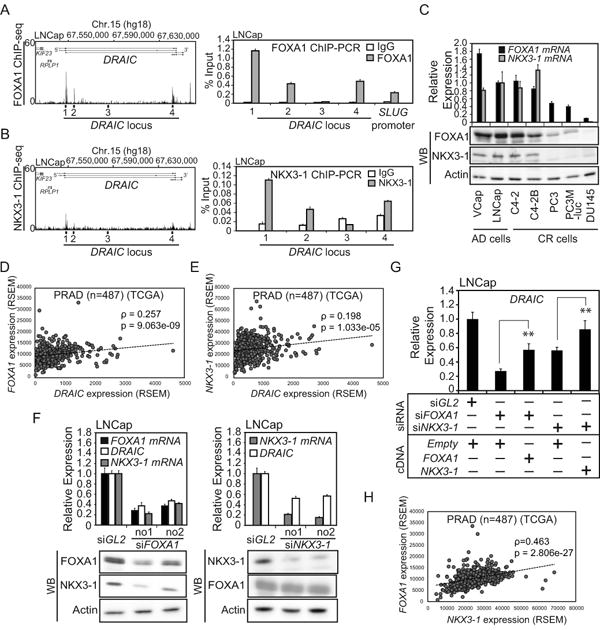

FOXA1 and NKX3-1 occupy the same regions where AR is recruited at DRAIC promoter

AR often co-localizes with other transcriptional factors across the prostate genome (27). Tan PY et.al. showed that the binding motifs of FOXA1 and NKX3-1 are highly enriched in AR ChIP-seq samples (27). In addition, FOXA1 has been reported to act as a pioneer factor that opens local chromatin structure to allow AR to be recruited (28–31). We therefore analyzed published FOXA1 and NKX3-1 ChIP-seq datasets (26,27) to examine the binding of these transcription factors to the DRAIC locus (Fig. 4A, B). Interestingly, ChIP-seq peaks of these two transcriptional factors overlapped with those of AR at the DRAIC locus (Fig. 4A, B, Fig. 3C). We confirmed by ChIP-PCR that Regions 1, 2 and 4 bind to FOXA1 and to NKX3-1 (Fig. 4A, B). Regions 1, 2 and 4 contain several ARE (androgen-responsive element) half-sites and several FOXA1 and NKX3-1 binding sites close to the AREs (Supplementary Fig. 3).

Figure 4. FOXA1 and NKX3-1 positively regulate DRAIC.

(A) Left: Published FOXA1 ChIP-seq (26) peaks in LNCap cells cultured in the growth medium. Right: FOXA1 ChIP-PCR was performed with cells in 10% FCS. SLUG promoter was used as a positive control (32). Rest as in Fig. 3D. (B) Left: Published NKX3-1 ChIP-seq (27) peaks in LNCap cells treated with Dihydrotestosterone (DHT). Rgith: NKX3-1 ChIP-PCR was performed with cells in 10% FCS. Rest as in Fig. 3D. (C) The mRNA and protein levels of FOXA1 and NKX3-1 were measured by RT-qPCR and western blotting, respectively. Rest as in Fig. 1C. (D and E) The correlation of levels of DRAIC and FOXA1 or DRAIC and NKX3-1 RNAs in prostate adenocarcinoma (PRAD) samples (n=487) from tier-3 RNA-seq data of TCGA. Spearman correlation coefficients and p-values are shown. (F) LNCap cells cultured in growth medium were transfected with siRNA against FOXA1, NKX3-1 or siGL2 for 72h. The RNA levels of DRAIC, FOXA1 and NKX3-1 and the protein levels of FOXA1, NKX3-1 and Actin were measured by RT-qPCR and western blotting, respectively. In RT-qPCR, the expression in siGL2 is set as 1. Rest as in Fig. 1C. (G) LNCap cells cultured in the growth medium were transfected with siRNA against FOXA1 no.1, NKX3-1 no.1 or siGL2 and 3μg expression vector of pcDNA3-FOXA1, -NKX3-1 or -Empty for 72 h. The expression of DRAIC was measured by RT-qPCR. The expression of DRAIC in siGL2 plus Empty vector cells is set as 1. ** indicates p-value<0.01. Rest as in Fig. 1C. (H) The correlation curve between FOXA1 and NKX3-1 RNAs in prostate adenocarcinoma (PRAD) samples (n=487). Rest as in Fig.4D, E.

The expression of DRAIC is positively regulated by FOXA1 and NKX3-1

Contrary to our expectation that FOXA1 is a pioneer factor for AR and should repress DRAIC, the expression pattern of FOXA1 and NKX3-1 was similar to that of DRAIC: lower in most CR cells (except C4-2) compared to the AD cells (Fig. 4C and Fig. 1E). RNA-seq data from prostate adenocarcinomas from the cBioPortal (n=487) show weak but statistically significant positive correlation between the expression of FOXA1 and DRAIC or NKX3-1 and DRAIC (Fig. 4D, E).

In addition, knockdown of FOXA1 or NKX3-1 decreased DRAIC levels (Fig. 4F). The siRNA-resistant forms of FOXA1 or NKX3-1 partially rescued the downregulation of DRAIC induced by the cognate siRNAs, ruling out the possibility of off-target effects of the siRNAs (Fig. 4G). FOXA1 or NKX3-1 therefore have an opposite effect on DRAIC expression compared to AR, suggesting that FOXA1 is not acting as a pioneer factor for AR at the DRAIC promoter.

Knockdown of FOXA1 also decreased NKX3-1 protein and mRNA (Fig. 4F). Indeed, the FOXA1 and NKX3-1 mRNA levels were positively correlated in clinical samples (Fig. 4H). We did not see any significant FOXA1 ChIP-seq peaks (26) at the NKX3-1 locus (data not shown), suggesting that FOXA1 stimulates NKX3-1 expression by an unknown indirect mechanism.

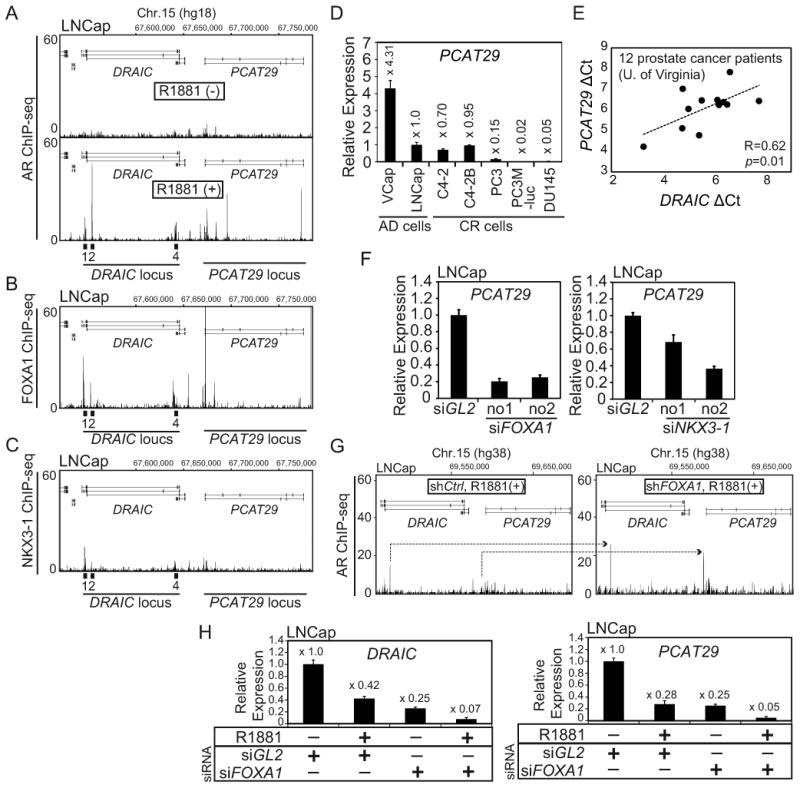

A lncRNA, PCAT29 is regulated by AR, FOXA1 and NKX3-1

Malik et.al. recently reported a tumor suppressive lncRNA, PCAT29, whose expression is repressed by AR (13). Interestingly, PCAT29 gene is located 20 kb downstream of DRAIC. We therefore analyzed published ChIP-seq dataset for AR, FOXA1 and NKX3-1 and identified that these transcriptional factors are also recruited to PCAT29 locus (Fig. 5A, B, C). The expression pattern of PCAT29 in a panel of prostate cancer cells is similar to that of DRAIC except for C4-2B cells (Fig. 5D and Fig. 1E). Since PCAT29 is not annotated in the level 3 data from TCGA, we used RNA from de-identified prostate cancer samples collected at UVA and used in a previous paper to analyze the correlation between DRAIC and PCAT29 (14). Q-RT-PCR of these lncRNAs showed a positive correlation between the expression of the two lncRNAs (Fig. 5E). From these results, we hypothesized that PCAT29 is regulated by FOXA1 and NKX3-1 in a manner similar to DRAIC. Indeed, siRNA against FOXA1 or NKX3-1 decreased PCAT29 expression (Fig. 5F, Fig. 4F).

Figure 5. A neighboring lncRNA, PCAT29 is also repressed by AR and activated by FOXA1 and NKX3-1.

(A) Published AR ChIP-seq (26) peaks in LNCap cells at DRAIC and PCAT29 loci in the absence (upper) or presence (lower) of R1881. (B) Published FOXA1 ChIP-seq (26) peaks in LNCap cells cultured in the growth medium at DRAIC and PCAT29 loci. (C) Published NKX3-1 ChIP-seq (27) peaks in LNCap cells treated with Dihydrotestosterone (DHT) at DRAIC and PCAT29 loci. (D) The expression of PCAT29 in a panel of prostate cancer cells was measured by RT-qPCR. Rest as in Fig. 1C. (E) The delta Ct values of DRAIC and PCAT29 (normalized to GAPDH) in 12 prostate cancer patients (University of Virginia) were subjected to Pearson correlation analysis. (F) The expression of PCAT29 after transfection of siRNA against FOXA1, NKX3-1 or siGL2 was measured by RT-qPCR. Rest as in Fig. 4F. (G) Published AR ChIP-seq results (30) show induction of AR binding (arrows) at DRAIC and PCAT29 loci in LNCap cells treated with shFOXA1 or shCtrl (negative control). R1881 is present in both cultures. (H) LNCap cells were treated with siGL2 or siFOXA1 for 72h in the absence or presence of R1881 (10 nM) for 24h. The expression of DRAIC (Left) and PCAT29 (Right) are measured by RT-qPCR. The expression in siGL2/R1881 (-) is set as 1. Rest as in Fig. 1C.

Jin et.al. recently reported that FOXA1 knockdown can shift or increase AR binding to selected sites (30). We analyzed their AR ChIP-seq data and found that shFOXA1 increases AR recruitment at DRAIC/PCAT29 cluster (Fig. 5G). Thus, FOXA1 actually decreases the recruitment of AR to the DRAIC/PCAT29 locus. Consistent with this, R1881 treatment or FOXA1 knockdown independently repress DRAIC and PCAT29, but together they repress both genes even further (Fig. 5H). This result suggests that instead of being a pioneer factor of AR, FOXA1 counters the action of AR at the DRAIC/PCAT29 cluster.

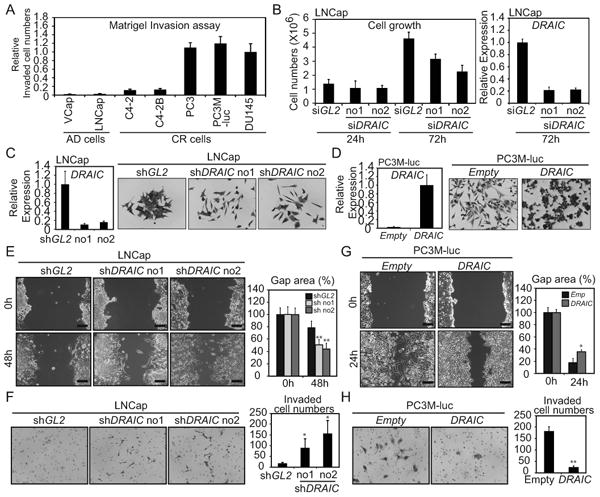

DRAIC represses cellular migration and invasion

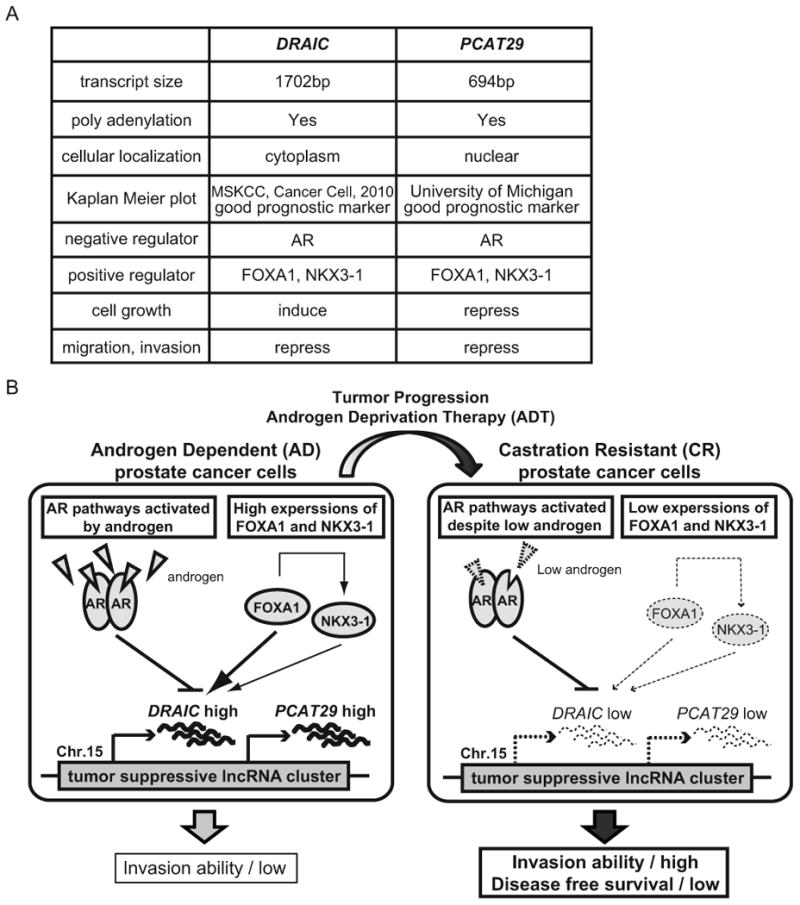

Like PCAT29 (13), DRAIC is a marker for good prognosis in prostate cancer (Fig. 2B), and so is expected to repress oncogenic phenotypes. PCAT29 has been reported to repress invasion and metastasis (13). The ability of a panel of prostate cancer cells to invade through Matrigel in a Boyden Chamber assay was anti-correlated with the level of expression of DRAIC in the same cells (Fig. 6A; Fig. 1E), suggesting that DRAIC, like PCAT29, represses invasion. Transient knockdown of DRAIC by siRNA in LNCap cells unexpectedly decreased cell numbers by about 30-50% (Fig. 6B), suggesting that DRAIC has a pro-proliferative function. When DRAIC was stably knocked down by shRNA in LNCap cells, the cell proliferation was similarly decreased (data not shown) but interestingly, the cell morphology was changed from cuboidal to fibroblast-like shape (Fig. 6C). Stable DRAIC overexpression in PC3M-luc cells, in contrast, showed the opposite phenotype, with a change in morphology from fibroblast shape to cuboidal shape (Fig. 6D). In a scratch assay to measure cell migration and in a Matrigel invasion assay, the migration and invasion of LNCaP cells is increased by DRAIC knockdown (Fig. 6E, F). In similar assays, the migration and invasion of PC3M-luc cells is decreased by DRAIC overexpression (Fig. 6G, H). Taken together, these results suggest that DRAIC promotes cell proliferation but inhibits cell migration and invasion. We summarized the similarities and differences between DRAIC and PCAT29 in Figure 7A.

Figure 6. DRAICrepresses cancer cell migration and invasion.

(A) The relative number of cells invaded through matrigel is normalized to number in DU145 cells. (B) Left; Proliferation of LNCap cells after transfection of siRNAs. Right; DRAIC RNA measured by RT-qPCR and normalized to GAPDH. Rest as in Fig. 1C. (C) LNCap transduced with lentivirus expressing shGL2, -shDRAIC no1 or no2. Left: DRAIC mRNA normalized to GAPDH. Rest as in Fig. 1C. Right: Cells stained by Crystal Violet. (D) PC3M-luc cells stably transfected with pcDNA3-DRAIC or pcDNA3-Empty. Left: DRAIC RNA normalized to GAPDH. The level in DRAIC overexpressing cells is set as 1. Rest as in Fig. 1C. (E) Scratch wound healing assay with LNCap cells stably expressing shGL2 or shDRAIC. Left: Representative images of scratch shown. Scale bar: 20μm. Right: gap area quantitated by Image J. Mean±S.D. n=5. ** : difference from shGL2 p<0.01. (F) Matrigel Invasion assay with LNCap expressing shGL2 or shDRAIC. Left: Invaded cells fixed in methanol, stained by Crystal Violet. Right: Number of invaded cells. Rest as in (E). (G) Scratch wound healing assay with Empty or DRAIC overexpressing PC3M-luc cells. Image and bar graph as in (E) *: difference from Empty p<0.05. (H) Matrigel invasion assay was performed using Empty or DRAIC overexpressing PC3M-luc cells. Rest as in (F).

Figure 7. Schematic representation of the proposed regulation of lncRNA cluster, DRAIC/PCAT29.

(A) Comparison of DRAIC and PCAT29. (B) In AD cells, even though AR activated by androgen is recruited to DRAIC/PCAT29 cluster to repress these two lncRNA, the high level of FOXA1 counters the repression of DRAIC/PCAT29 by AR and induces the transcription of these lncRNAs. NKX3-1, which is indirectly up-regulated by FOXA1, contributes to the induction of DRAIC/PCAT29. During tumor progression, the expression of FOXA1 and NKX3-1 is downregulated and AR pathways are differentially activated despite low androgen in CR cells. The decrease of FOXA1 enhances AR recruitment to the cluster and represses DRAIC/PCAT29. ADT selects for cells with decreased DRAIC expression. The decrease of tumor suppressive lncRNAs, DRAIC and PCAT29, leads to higher invasion ability and lower disease free survival in prostate cancer patients.

Discussion

The regulation of DRAIC and PCAT29 genes is remarkably similar to that we reported for the miR-99 family (14,15). AR is recruited to the pri-miR-99a promoter and represses transcription in concert with EZH2 (14,15). Considering that AR is recruited to broad regions around DRAIC (and the transcript variants) and PCAT29 gene, it is conceivable that a chromatin looping mechanism following AR recruitment is involved to produce a large domain with gene suppression.

FOXA1 and NKX3-1 have been variably thought to be tumor suppressive (32,33) and oncogenic (34,35). In the regulation described here, the two factors appear to be tumor suppressive in that their levels are decreased in CR cells and they are positive transcription factors for DRAIC and PCAT29, both of which decrease migration and invasion and predict good prognosis. We propose a model that FOXA1 and NKX3-1 induce the expression of DRAIC/PCAT29 in AD prostate epithelial cells but are downregulated in CR cells, leading to the decrease of DRAIC (Fig. 7B). Moreover, DRAIC is further repressed in the CR cells by differently activated androgen-responsive pathways (Fig. 7B).

FOXA1 is well known to be a pioneer factor and stimulates AR-mediated gene regulation (28–31). But our study clearly shows that FOXA1 counters the repression of DRAIC/PCAT29 by AR (Fig. 5H). Jin et. al. showed that excess of FOXA1 opens up an excess of chromatin regions and ends up diluting AR across the genome thereby indirectly inhibiting specific AR binding events (30). Therefore we need to study whether FOXA1 directly or indirectly represses AR recruitment to DRAIC/PCAT29 cluster. Similarly, NKX3-1 is known to be positively regulated by AR and facilitates regulation of the AR downstream genes by associating with AR (27). However, at the DRAIC/PCAT29 locus NKX3-1 has the opposite effect of AR on gene expression, suggesting a different mode of action.

Our functional analysis showed that DRAIC represses migration and invasion (Fig. 6) just like PCAT29 (13). However, knockdown of DRAIC represses cell proliferation (Fig. 6B) while knockdown of PCAT29 induces proliferation (13), suggesting that all functions of these lncRNA are not identical. This is borne out by the different cellular localization of DRAIC (cytoplasmic) and PCAT29 (nuclear) (13). Future studies will analyze whether DRAIC and PCAT29 synergize with each other in repressing cell migration and invasion in vitro and in vivo.

Although it is tempting to propose that DRAIC represses epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT), preliminary results suggest that levels of mRNA involved in EMT are unchanged by DRAIC knockdown or overexpression (data not shown). Diverse mechanisms have been proposed by which lncRNAs could regulate many phenotypes at transcriptional and post-transcriptional levels (36). Thus a detailed analysis is needed to determine the downstream targets of this cytoplasmic lncRNA and the molecular mechanism by which DRAIC regulates cellular migration and invasion.

It will be interesting to investigate in the future whether DRAIC/PCAT29 expression levels are related to the Gleason grade and whether they are useful as an independent prognostic biomarkers of prostate cancer. The results reported here highlight that a thorough study of lncRNAs altered during prostate cancer genesis and progression will be very important for improving our understanding and the therapy of this cancer.

Finally, DRAIC expression predicts good prognosis in a wide range of malignancies from many other tissues, suggesting that it is an important and ubiquitous tumor suppressor. Whether the mechanism by which clinical progression is suppressed is the same in all these tumors, and whether PCAT29 has a similar anti-progression effect in these tumors as in prostate cancer, will be important questions for the future.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank members of the Prostate Cancer Research Working group at UVA and the Dutta laboratory for advice and helpful discussions.

Financial support: This work was supported by P01CA104106 from NIH to AD

Footnotes

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest: No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

References

- 1.Karantanos T, Corn PG, Thompson TC. Prostate cancer progression after androgen deprivation therapy: mechanisms of castrate resistance and novel therapeutic approaches. Oncogene. 2013;32:5501–11. doi: 10.1038/onc.2013.206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen CD, Welsbie DS, Tran C, Baek SH, Chen R, Vessella R, et al. Molecular determinants of resistance to antiandrogen therapy. Nat Med. 2004;10:33–9. doi: 10.1038/nm972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Majumder PK, Sellers WR. Akt-regulated pathways in prostate cancer. Oncogene. 2005;24:7465–74. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Negishi M, Wongpalee SP, Sarkar S, Park J, Lee KY, Shibata Y, et al. A new lncRNA, APTR, associates with and represses the CDKN1A/p21 promoter by recruiting polycomb proteins. PLoS One. 2014;9:e95216. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0095216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dey BK, Pfeifer K, Dutta A. The H19 long noncoding RNA gives rise to microRNAs miR-675-3p and miR-675-5p to promote skeletal muscle differentiation and regeneration. Genes Dev. 2014;28:491–501. doi: 10.1101/gad.234419.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mueller AC, Cichewicz Ma, Dey BK, Layer R, Reon BJ, Gagan JR, et al. MUNC: A lncRNA that induces the expression of pro-myogenic genes in skeletal myogenesis. Mol Cell Biol. 2014 doi: 10.1128/MCB.01079-14. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kumar P, Anaya J, Mudunuri SB, Dutta A. Meta-analysis of tRNA derived RNA fragments reveals that they are evolutionarily conserved and associate with AGO proteins to recognize specific RNA targets. BMC Biol. 2014;12:78. doi: 10.1186/s12915-014-0078-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cesana M, Cacchiarelli D, Legnini I, Santini T, Sthandier O, Chinappi M, et al. A long noncoding RNA controls muscle differentiation by functioning as a competing endogenous RNA. Cell. 2011;147:358–69. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.09.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yuan J, Yang F, Wang F, Ma J, Guo Y, Tao Q, et al. A long noncoding RNA activated by TGF-β promotes the invasion-metastasis cascade in hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Cell. 2014;25:666–81. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2014.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wahlestedt C. Targeting long non-coding RNA to therapeutically upregulate gene expression. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2013;12:433–46. doi: 10.1038/nrd4018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yang L, Lin C, Jin C, Yang JC, Tanasa B, Li W, et al. lncRNA-dependent mechanisms of androgen-receptor-regulated gene activation programs. Nature. 2013;500:598–602. doi: 10.1038/nature12451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Prensner JR, Chen W, Iyer MK, Cao Q, Ma T, Han S, et al. PCAT-1, a long noncoding RNA, regulates BRCA2 and controls homologous recombination in cancer. Cancer Res. 2014;74:1651–60. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-3159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Malik R, Patel L, Prensner JR, Shi Y, Iyer MK, Subramaniyan S, et al. The lncRNA PCAT29 Inhibits Oncogenic Phenotypes in Prostate Cancer. Mol Cancer Res. 2014;12:1081–7. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-14-0257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sun D, Lee YS, Malhotra A, Kim HK, Matecic M, Evans C, et al. miR-99 family of MicroRNAs suppresses the expression of prostate-specific antigen and prostate cancer cell proliferation. Cancer Res. 2011;71:1313–24. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-1031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sun D, Layer R, Mueller aC, Cichewicz Ma, Negishi M, Paschal BM, et al. Regulation of several androgen-induced genes through the repression of the miR-99a/let-7c/miR-125b-2 miRNA cluster in prostate cancer cells. Oncogene. 2014;33:1448–57. doi: 10.1038/onc.2013.77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mueller aC, Sun D, Dutta a. The miR-99 family regulates the DNA damage response through its target SNF2H. Oncogene. 2013;32:1164–72. doi: 10.1038/onc.2012.131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cerami E, Gao J, Dogrusoz U, Gross BE, Sumer SO, Aksoy BA, et al. The cBio cancer genomics portal: an open platform for exploring multidimensional cancer genomics data. Cancer Discov. 2012;2:401–4. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-12-0095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Taylor BS, Schultz N, Hieronymus H, Gopalan A, Xiao Y, Carver BS, et al. Integrative genomic profiling of human prostate cancer. Cancer Cell. 2011;18:11–22. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2010.05.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Weinstein JN, Akbani R, Broom BM, Wang W, Verhaak RG, McConkey D, et al. Comprehensive molecular characterization of urothelial bladder carcinoma. Nature. 2014;507:315–22. doi: 10.1038/nature12965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Collisson Ea, Campbell JD, Brooks AN, Berger AH, Lee W, Chmielecki J, et al. Comprehensive molecular profiling of lung adenocarcinoma. Nature. 2014;511:543–50. doi: 10.1038/nature13385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Decker KF, Zheng D, He Y, Bowman T, Edwards JR, Jia L. Persistent androgen receptor-mediated transcription in castration-resistant prostate cancer under androgen-deprived conditions. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:10765–79. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tewari AK, Yardimci GG, Shibata Y, Sheffield NC, Song L, Taylor BS, et al. Chromatin accessibility reveals insights into androgen receptor activation and transcriptional specificity. Genome Biol. 2012;13:R88. doi: 10.1186/gb-2012-13-10-r88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thalmann GN, Anezinis PE, Chang S, Thaimann N, Hopwood VL, Pathak S, et al. Androgen-independent Cancer Progression and Bone Metastasis in the LNCaP Model of Human Prostate Cancer Model of Human Prostate Cancer. Cancer Res. 1994;54:2577–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kretz M, Siprashvili Z, Chu C, Webster DE, Zehnder A, Qu K, et al. Control of somatic tissue differentiation by the long non-coding RNA TINCR. Nature. 2013;493:231–5. doi: 10.1038/nature11661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rajan P, Sudbery IM, Villasevil MEM, Mui E, Fleming J, Davis M, et al. Next-generation sequencing of advanced prostate cancer treated with androgen-deprivation therapy. Eur Urol. 2014;66:32–9. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2013.08.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yu J, Yu J, Mani RS, Cao Q, Brenner CJ, Cao X, et al. An integrated network of androgen receptor, polycomb, and TMPRSS2-ERG gene fusions in prostate cancer progression. Cancer Cell. 2010;17:443–54. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2010.03.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tan PY, Chang CW, Chng KR, Wansa KDSA, Sung WK, Cheung E. Integration of regulatory networks by NKX3-1 promotes androgen-dependent prostate cancer survival. Mol Cell Biol. 2012;32:399–414. doi: 10.1128/MCB.05958-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cai C, He HH, Gao S, Chen S, Yu Z, Gao Y, et al. Lysine-Specific Demethylase 1 Has Dual Functions as a Major Regulator of Androgen Receptor Transcriptional Activity. Cell Rep. 2014;9:1618–27. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.11.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Robinson JLL, Hickey TE, Warren aY, Vowler SL, Carroll T, Lamb aD, et al. Elevated levels of FOXA1 facilitate androgen receptor chromatin binding resulting in a CRPC-like phenotype. Oncogene. 2014;33:5666–74. doi: 10.1038/onc.2013.508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jin HJ, Zhao JC, Wu L, Kim J, Yu J. Cooperativity and equilibrium with FOXA1 define the androgen receptor transcriptional program. Nat Commun. 2014;5:3972. doi: 10.1038/ncomms4972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mills IG. Maintaining and reprogramming genomic androgen receptor activity in prostate cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2014;14:187–98. doi: 10.1038/nrc3678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jin HJ, Zhao JC, Ogden I, Bergan RC, Yu J. Androgen receptor-independent function of FoxA1 in prostate cancer metastasis. Cancer Res. 2013;73:3725–36. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-3468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bowen C, Bubendorf L, Voeller HJ, Progression T, Slack R, Willi N, et al. Loss of NKX3.1 Expression in Human Prostate Cancers Correlates with Tumor Progression. Cancer Res. 2000;60:6111–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gerhardt J, Montani M, Wild P, Beer M, Huber F, Hermanns T, et al. FOXA1 promotes tumor progression in prostate cancer and represents a novel hallmark of castration-resistant prostate cancer. Am J Pathol. 2012;180:848–61. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2011.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Xu LL, Srikantan V, Sesterhenn IA, Augustus M, Dean R, Moul JW, et al. Expression profile of an androgen regulated prostate specific homeobox gene NKX3.1 in primary prostate cancer. J Urol. 2000;163:972–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dey BK, Mueller AC, Dutta A. Long non-coding RNA as emerging regulators of differentiation, development, and disease. Transcription. 2014 doi: 10.4161/21541272.2014.944014. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.