Abstract

The current attention that is being paid to college sexual assault in policy circles and popular media overlooks a critical issue: the possible role played by the urban social environment in intimate partner violence (IPV) risk for the large number of urban commuter college students throughout the USA and beyond. This article helps to illuminate this dynamic using qualitative research collected at an urban commuter campus in New York City. Specifically, we conducted focus groups and in-depth interviews with 18 female undergraduate students, exploring the nature and consequences of IPV in students’ lives, perceived prevalence of IPV, and resources for addressing IPV. Our results indicate that college attendance may both elevate and protect against IPV risk for students moving between urban off- and on-campus social environments. Based on this, we present a preliminary model of IPV risk for undergraduate women attending urban commuter colleges. In particular, we find that enrolling in college can sometimes elevate risk of IPV when a partner seeks to limit and control their student partner’s experience of college and/or is threatened by what may be achieved by the partner through attending college. These findings suggest a role for urban commuter colleges in helping to mitigate IPV risk through policy formulation and comprehensive ongoing screening and prevention activities.

Keywords: Intimate partner violence, Urban social environment, Commuter college students

Introduction

Sexual violence on college campuses has recently emerged as an issue of urgent policy and programmatic concern in the USA, but it is only one of the several types of violence that threaten the health, well-being, and academic success of college women.1–3 The risk for intimate partner violence (IPV), including “physical, sexual, or psychological harm by a current or former partner or spouse,”1 among women is greatest between the ages of 18 to 24 years,2 a period when many women enter college. While the prevalence of IPV among students internationally has been estimated to range from 17 to 45 % for physical assaults in the last year,4 women are far more likely than men to experience sexual and physical violence,2,5 or to be killed as result of IPV.6,7 In a sample of American college students, 43 % of women (vs. 28 % of men) reported having experienced physical abuse, sexual abuse, or other forms of IPV (e.g., controlling behavior, verbal abuse, excessive calling or texting, etc.), and over half of the students reported having these experiences while in college.8 Additionally, women are more likely than men to experience physical limitations and overall performance and cognitive impairment as a result of IPV,9 which elevate their risk for college interruption or permanent dropout.

While a substantial amount of research reports prevalence and types of IPV in college women, most studies have not examined the context within which women attending college experience IPV, and none that we know of have examined these experiences among urban commuter college women in particular. Instead, most studies of commuter students focus on examining the academic success, or campus involvement of these students.10–13 Some college datasets include data on campus location (urban vs. rural, etc.) and student commuting. However, studies have yet to be conducted that systematically examine the linkages between these and other important student characteristics and IPV. Two data hurdles associated with these analyses include (1) the limited nature of the IPV data currently collected by institutions,1 and (2) appropriately parsing out commuter student characteristics, particularly those that may be related to IPV risk (e.g., income or employment status, household composition, area of residence, etc.).12

What the data do appear to show, however, is that commuter college students make up the vast majority of college students nationwide; by some estimates, only about 15 % of undergraduates live on campus.14 This article describes the IPV experiences of female undergraduate students at the City University of New York (CUNY), the largest urban public university system in the USA,15 where almost all students are commuters from urban neighborhoods2 with diverse backgrounds. In Fall 2013, CUNY undergraduates were 30 % Hispanic, 26 % Black, 24 % White, and almost 20 % Asian/Pacific Islander; 38 % were foreign-born and 39 % had annual household incomes below $20,000.16 Additionally, close to half of CUNY undergraduates are in the first generation in their family to attend college, 15 % are supporting children, and 30 % are working for pay for more than 20 h per week.16

This profile of CUNY students suggests that, at least demographically speaking, many of them may be at elevated risk for IPV. In NYC, Black and Hispanic women experience higher rates of IPV than White and Asian women. Additionally, women living in very low income neighborhoods in NYC (loosely corresponding to a median household income of under $20,000) are more likely to visit an emergency department, be hospitalized, or be killed as a result of IPV.17 While IPV prevalence data for foreign-born women is limited, immigration status can function as a risk factor for IPV.18 And disturbingly, a study conducted in NYC shows that women who are killed by intimate partners are almost twice as likely to be foreign-born as women who are killed in other ways.19

Despite this potentially elevated risk, it appears that commuter colleges often struggle to deliver health and preventive services to students when compared to residential colleges. For instance, a study examining availability of emergency contraceptive pills found that these were more likely to be offered at residential colleges and colleges with equal numbers of residential and non-residential students than at colleges with a majority of commuter students.20 Another study looking at student substance use prevention activities on 100 community college campuses found that the presence of residence halls was associated with increased activities. More comprehensive studies of college health services unfortunately do not include student residence status as a variable.21 At CUNY, many campuses offer health and counseling centers, peer education programs, and in recent years, an innovative health mobilization effort called Healthy CUNY has been launched.22 Understanding how CUNY female undergraduates perceive these programs and services may be an important step toward delivering effective IPV-related services to this group.

Additionally, there is substantial research suggesting that the commuter student’s social experience can differ from that of residential college students in ways that may bear on IPV risk. For example, research indicates that commuter students often feel low levels of connectedness to their college campus,11,10 likely as a result of competing work and family responsibilities.12 At the same time, members of commuter students’ support networks may be less familiar with college demands and stresses.13 IPV disclosure and help-seeking is often dependent on having access to relevant information and building trusting relationships.23 Therefore, disconnectedness from on-campus and off-campus social environments may generate perceptions of low social support, which can lead to IPV-related stigma and social isolation,24 both known risk factors for IPV.25

In this exploratory study, we thus seek to address a gap in the literature by articulating some of the unique dynamics of IPV risk for urban commuter female students. We discuss participants’ perceptions of (1) college attendance as a risk factor for IPV, (2) the impact of IPV on academic success, (3) IPV occurrence across social settings, and (4) college resources to address IPV. Applying an urban health lens, we then discuss the social environments of urban commuter students and suggest ways in which the college setting, as a major social institution, can help to address IPV in urban communities. A preliminary model of IPV risk for undergraduate women attending urban commuter colleges is also discussed.

Methods

Data for this project were collected via focus groups and in-depth interviews with undergraduate female students at a CUNY 4-year college. The inclusion criteria for the study were being 18 or over, female, and an undergraduate student. Students were recruited for data collection activities via posters and emails advertising sessions in which IPV would be discussed but not requiring direct experience in this area. A total of 46 female students responded to study flyers via email or telephone. In total, 18 students were enrolled in the study (25 did not respond to further calls, two were not eligible, and one refused participation). All students provided written informed consent. The CUNY Institutional Review Board approved this study.

A total of four focus groups (12 students) and six in-depth qualitative interviews with six additional students were conducted, all lasting approximately 1 to 1.5 h. Researchers scheduled at least six students for each focus group, but unexpected issues related to child care, transit, and work, among others, often challenged students’ schedules. Attendance for the focus group sessions thus ranged from two to four students. Separate data collection guides were used for the focus group and interview sessions. Focus groups investigated topics including definitions of IPV, perceived causes and consequences of IPV, perceived prevalence, and resources for addressing IPV. Upon completion of the focus group sessions, students were given a short questionnaire in which they privately answered a question on whether they had ever directly experienced (i.e., in their own intimate relationship) any form of abuse (yes/no). Student in-depth interviews covered many similar topics but were more focused on individual IPV experiences: both directly experienced and indirectly witnessed.

Qualitative data analysis included a basic thematic analysis performed by the authors, focusing on the research topic areas and attending to both etic and emic themes.26 Analytic memos were also developed as a basis for discussion and reconciliation of conflicting interpretations. Lastly, the investigators used triangulation of methods (focus groups versus in-depth interviews) as well as multiple analysts to increase credibility.27,28 To enhance dependability and confirmability, two key aspects of qualitative research soundness,27 the investigators documented the progress of data collection and analysis.

Results

Sample Characteristics

Of the 18 participants, 13 identified as Hispanic, two as non-Hispanic Black/African-American, two as Asian, and one as non-Hispanic White. The median age was 23.5 years (range 18–52 years), and five students were foreign-born. Common college majors among participating students included economics, health services administration, psychology, and sociology, and students ranged from freshman to senior status.

Table 1 summarizes directly experienced IPV by student characteristics. The vast majority of participants (13 out of 18) reported experiencing some form of IPV directly. Nine out of 12 students who completed focus group sessions reported direct experiences of IPV during the private post-focus group questionnaire. All six students who completed interview sessions disclosed witnessing IPV in other people’s romantic relationships, typically at close range (victims of IPV were family members or close friends), and four disclosed experiencing IPV in their own romantic relationships. Of the two who did not report direct/self-experienced IPV, one reported direct experience of maternal violence, as well as instigating IPV toward a male partner. The other witnessed female-perpetrated IPV toward a close male relative.

TABLE 1.

Student characteristics and directly experienced IPV (n = 18)

| Directly experienced IPV | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Total | Yes | No |

| Age group | |||

| <24 | 10 | 8 | 2 |

| >25 | 8 | 5 | 3 |

| Hispanic | |||

| Yes | 13 | 10 | 3 |

| No | 5 | 3 | 2 |

| Foreign born | |||

| Yes | 5 | 3 | 2 |

| No | 13 | 10 | 3 |

| Inquiry modality | |||

| Post-focus group questionnaire | 12 | 9a | 3 |

| Face-to-face interview | 6b | 4 | 2c |

aOnly one disclosed directly experienced IPV during focus group session

bAll witnessed IPV in someone else’s relationship

cOne acknowledged both maternal abuse and abusive behavior (physical and non-physical) toward male partner.

College Attendance as a Risk Factor for IPV

We first explore the role of college attendance as a risk factor for IPV. We note that this is not a topic that we asked about directly, but instead one that emerged emically, through the identification of patterns in the data. According to our participants, enrolling in college was often seen as a threat to partners who then sometimes used psychological violence in return. As a focus group participant said, “…sometimes, if he sees you studying, he might be like, ‘Why are you studying for? You don’t need that, you don’t need school. That’s not going to give you anything, I give you everything.’ And you’re like, okay, and you put that aside. But then, at the end, you would sometimes have to do it sneaky, or stay in school longer. And he’s like, ‘Oh, where are you? Why aren’t you here? Are you with someone else?’” Other focus group participants noted that they knew of people who had dropped out of school for these reasons. Along similar lines, one interviewee spoke about the increased surveillance she was under once she started college. She said, “At one point, he [her boyfriend at the time, later her husband] told me, ‘You don’t exchange numbers with the males; you only, if you need to do work, you do it with girls.’ So he psychologically made me feel like [a] threat.” She believed that her partner initiated this form of psychological abuse because a previous girlfriend had cheated on him when she started college. Thus, fears that a student partner will meet someone else or seek other kinds of opportunities outside of the relationship are not necessarily unfounded.

An interviewee who had gained employment while in college communicated how her increased independence, “having a job and being out in public,” triggered physical violence and led to her dropping out of college: “…I had my own income. So I didn’t really need him anymore, because I had money to move around. […] [Work] required me leaving and going out into the public, and I know that’s what pissed him off. He said, ‘Oh really? Then I’m going to make sure people know that you have someone.’ And that’s when you know they pinned me down to the floor.” The partner and his friends marked her neck with hickeys. The student continued, “I didn’t officially withdraw, but I stopped going to [to school] because I was like, I can’t keep going through this every time I have to go out in public. I’m walking around with these huge hickeys that look like somebody just literally punched me in my neck. So I was embarrassed. I was like, I can’t do this, you know let me just do what he says he wants me to do, and I’ll just play my role as much as I can without getting him upset.”

Another interviewee mentioned that while she was in college, she and her husband at the time, who was prone to “name-calling” and “aggressive outbursts of anger,” had gone to marital counseling. The therapist they saw explained that the verbal abuse might be resulting from her husband’s clinical depression. Explaining his depression, this interviewee noted that her husband had been “unemployed for about—he’s still unemployed—like three or more years. [He] couldn’t find a job, only had half of an associate’s degree so he’s kind of stuck, you know, financial stress. […] He couldn’t finish school because he had loans that were in default and then he had gotten laid off and then couldn’t just never bounce back.” While this interviewee did not explicitly connect the verbal abuse with her college attendance, her husband’s negative experiences with school highlight this as a possibility.

Other causes and forms of abuse were discussed by students in less depth, but are worth noting. For instance, some participants mentioned that female students are often financially dependent on partners while in college, which can put them at risk for economic abuse. As one interviewee said, “He has the money. And even if you manage to get financial aid, financial aid don’t cover the books, you cover your books. So, that might be the problem, too. You won’t be able to study if you don’t have the book, and he refuses to buy you the book because he doesn’t want you to go to school…” While students identified partner insecurity and low self-esteem, often rooted in lagging behind academically or financially, as the main driver for increased IPV in the situations described above, they also repeatedly touched on other causes of IPV that are not related to college attendance, like history of family abuse and thinking that abusive behavior is the norm in relationships.

Last, we note that some focus group participants described how attending college (or getting a job) could potentially be empowering for a woman in an abusive relationship and possibly help her leave such a relationship. One student said that a woman might say to herself, “‘I have to make myself in a position where I can leave,’ so they start to go back to school, or do some kind of training to get a job. A woman could, you know, turn it around and empower herself, trying to get out.” In a similar vein, one interviewee spoke about how college helped her after a period of emotional abuse and cheating by her husband. She said, “…being around school and then meeting other people that are in your field, that helped also because it motivates you to do much better. It takes the focus out of thinking about what he’s doing now…”

IPV and Academic Performance

Students in our study spoke extensively about the stress that can result from IPV and how this can interfere with meeting academic demands. As one interviewee said, “Definitely the self-esteem went down while I was in that [abusive] relationship. You begin to wonder what happens to you or what did you do to, I guess, deserve it. And just the stress, it’s very stressful. A lot of emotional stress, definitely [a] huge distraction for school, work, just overall performance kind of goes down.”

In addition to creating stress, many students also conveyed that controlling relationships can directly impact grades and progress toward degree by interrupting the time required to study. A focus group participant who had experienced IPV directly vividly explained this (note that this student also introduced the impact of physical and sexual violence on academics): “It’s horrible. You don’t have time to study, you have to tend to this man’s every need…For example, if he’s home at--if you finish class at five, and he’s home at six, you got to run home, cook, clean, do whatever you can in that hour before he’s home and starts stomping around. And then, even then, you still have to tend to his every need. […] It’s never you. You can’t sit down and study. You can’t do any of that. And your grades show that […] I mean, you’re taking a test and all that’s on your mind is, like, your arm hurts because of how he pushed you yesterday, or your head is throbbing, or you didn’t get enough sleep last night because he forced himself on you.”

Students also sometimes dropped out of school entirely as a result of the shame from experiencing IPV. The situation of the interviewee who had been forcibly physically marked by her male partner illustrates this further (see previous section).

Exposure to IPV Across Social Settings

We asked students to assess the frequency of IPV among women they knew through school versus women they knew outside of school. Many students, in both focus groups and interviews, expressed difficulty in assessing how common IPV is in the lives of other students. When asked using a structured question, students said frequency could range from “rarely but sometimes” to “very frequently.” In focus groups, many justified their responses by talking about the college experience and their own friends. For instance, one focus group participant stated, “…with college students in general, especially here, relationship violence occurs more than we might think it does.” Another focus group participant expressed that IPV “rarely but sometimes occurs just because, like obviously, I don’t know everybody here, but then among the small group of people I know, I am aware of relationship violence that has been experienced.”

When asked specifically about IPV among women they know outside of college, all students but one (17 out of 18) rated the frequency of occurrence as being higher among women outside of college than among students; most participants thought that IPV occurs “somewhat frequently” or “very frequently” among women they know outside of college. In explaining their responses, students cited the IPV experiences of friends, people from church or other communities they belong to, and often mentioned hearing IPV experiences taking place among neighbors or seeing what looked like IPV on the streets. One focus group participant justified a “very frequently” response to this question by saying: “…next door to my house, they’re always yelling. You feel stuff, like he’s hitting, you hear it. You hear something thrown around. It’s like they’re always yelling, he’s always screaming at her and I hear her crying. And upstairs, the guy, his parents, the father used to hit the mother and he lives upstairs with them. He would put the music really, really loud, but you [could] hear them arguing.”

Perceived and Desired Resources

None of the students’ immediate responses to a question about the ways in which they would address IPV included the college as a site for resources. Rather, students’ immediate responses consisted of getting “a restraining order, get out of the city, the state,” going to the “cops,” or “the hospitals,” or “church,” or using entertainment to distract themselves. Although going to family and close friends for help was also part of the students’ immediate responses, hesitancy often accompanied these remarks, as expressed by one student: “I guess the most immediate action we would take is to talk to one of the closest friends or family members. Then again […] friends or family members may be too opinionated, so I guess the most wise thing is to go visit, like, a counseling center.” Upon discussing counseling services as an option, college-based counseling was slow to emerge as a resource and in some cases emerged in a way that suggested doubt about availability. When asked where she might seek counseling, one focus group participant said, “Right here at [name of college] if they—if they had the resource available.”

When the students were asked specifically about which campus resources, if any, they would use to address IPV, the college’s counseling center became the most cited resource. Although there was fairly widespread awareness of the existence of the counseling center, few knew details of services provided (and in particular that counselors there could help with IPV-related issues) or where it was, or had considered using it. Additionally, after the counseling center was introduced during these discussions, concerns regarding mandated reporting and privacy and anonymity emerged. The potential for seeking the help of professors or other college staff with whom comfort or trust has been established over time was also mentioned. The college’s health center was only cited by two students, one of whom was uncertain of this site as an IPV resource: “Let me ask you [directed to investigator], the health center. You know, I’m not too familiar with the services they offer. I’m aware of some, but would they be one of the resources on campus?”

We also had the opportunity to learn participants’ suggestions for promoting the college’s IPV resources. These suggestions were primarily focused on creating a culture of awareness on campus in order to reduce stigma and encourage women’s ability to recognize and avoid violent relationships. A student who had experienced IPV in her own relationship captured this by saying: “Domestic violence was never promoted or made aware to us. I think ads would have helped, if we would have known, maybe we [would] get help.” Students also seemed to prefer continuous efforts to raise awareness, rather than one-time events. In a student’s own words: “Last semester, I’m not sure whether it was a week, or whatever, there were t-shirts about violence. […] But [I’d recommend] ongoing [efforts], probably on the website.” In discussing the counseling center’s services, the majority of students expressed a desire for more visibility of staff skills in working with women experiencing IPV.

Limitations

In addition to the strengths described in our methods section, this study has several limitations that should be taken into consideration. First, the project likely attracted student participants who were especially interested in IPV, worried about IPV, and/or experiencing IPV. This meant that our participants may have been able to offer a depth of thought on this topic that other students would not and thus they should not be considered a representative sample. Additionally, our small sample size and the descriptive nature of the study do not allow us to make any comparisons based on participants’ characteristics. We should also note that while our small sample size was partially by design, given that we were collecting in-depth qualitative data, we were disappointed that we were not able to assemble slightly larger focus groups. We believe these outcomes were largely the result of the busyness of commuter students (who often have full-time jobs, families, and other matters to attend to outside of the college, which often come up unexpectedly) and to the sensitivity of the topic. At the same time, the smaller focus groups may have helped participants feel more comfortable engaging in a discussion of IPV.

Discussion

While the notion that commuter college students must bridge different social worlds has long been present in the literature,13 this exploratory study highlights significant ways in which commuter college attendance may shift the power dynamics of intimate relationships and the opportunities for elevated violence this can create. Applying an urban lens to our analysis provides further insights into this data and suggests some implications for intervention. Coutts and Kawachi draw our attention to three features of urban places that can help us think about influences on health. These are the service environment, the physical environment, and the social environment.29 While the physical environment may indeed play a role in IPV risk, we will focus our discussion on the two social environment participants reported on on-campus and off-campus social environments. We conceptualize the service environments at both of these sites as being closely intertwined with the social environments.

Regarding the off-campus urban social environment, though our data do not extensively address this topic directly, we focus our attention on the vivid descriptions participants provided of violence experienced by women they knew outside of campus, situations that often seemed to take place in their home neighborhoods. Research indicates that neighborhood social disadvantage can increase risk of IPV through numerous possible pathways, including stress resulting from disadvantage, residential instability, reduced social ties between neighbors, and reduced ability to organize and advocate for services to help address IPV.30–32 Students attending commuter colleges in New York City live in neighborhoods that are distinct from one another in innumerable ways when it comes to social life, and characterizing them as a group is close to impossible. It is worth noting though that commuter students tend to be less affluent than residential college students.33,34 Thus, while they may be unlikely to be living in the poorest neighborhoods in a city, they are also highly unlikely to be living in the most affluent neighborhoods. A report from the New York City Mayor’s Office to Combat Domestic Violence sheds some light on the nature of risk in these socioeconomically in-between neighborhoods. Specifically, the report shows that in New York City, the frequency of family homicide (the primary outcome discussed) tends to increase as median household income decreases.35 Those neighborhoods that fall in the middle of this gradient may experience risk of severe family violence that is also between that of poorer and more affluent neighborhoods. These data appear to fit with the proximity to violent situations that some students described in their neighborhoods. Exposure to violence in these settings may set the tone for increased risk of violence in students’ intimate relationships. There is evidence, for instance, that exposure to community violence can lead to victimization and perpetration of violence in other settings.36

The on-campus social environment, on the other hand, stands out in our data as representing two important dynamics. First, our data suggest that a student’s transition from the off-campus social environment into a commuter college setting may increase risk of IPV by exacerbating insecurities for some non-student/unemployed partners who then may increase their efforts to control the student partner. These actions in turn affect how the student participates in academic life and often have negative academic consequences. At the same time, the on-campus social environment represents a site that may help to mitigate IPV risk both short-term (primarily through service offerings) and longer-term through the forms of financial independence a college degree may offer. However, our data strongly show that the services at the college studied are not currently perceived as addressing IPV, though as we learned through verbal communication with staff, the campus does offer screening for IPV during counseling, peer education groups, and an annual awareness-raising event.

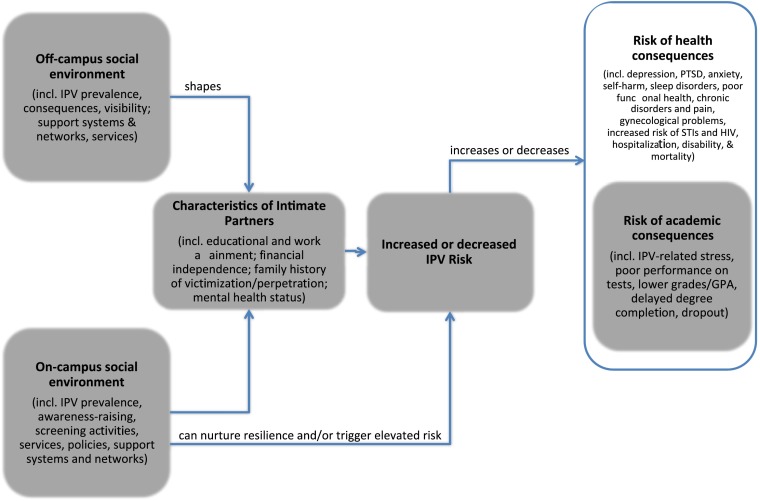

Thus, our analysis indicates that in some cases, the movement across social environments (college, home, work, family, etc.), and particularly the shifts between the social world of the intimate partner (represented here ecologically by the off-campus urban social environment) to the social world of college, may elevate risk for some female students. In other cases, moving through college, achieving in the academic realm, and being exposed to new people and aspirations may lower the risk of IPV. Figure 1 depicts some of these relationships graphically, using shaded boxes for the topics on which our study provides primary data.

FIG. 1.

A preliminary conceptual model of IPV risk for undergraduate women attending urban commuter colleges.

A sense of this complex risk dynamic may enrich and help to tailor how we think about interventions to prevent and address IPV on urban commuter campuses, essential activities given the lifetime health protection offered by increased levels of education.37 Current approaches often focus on one-time awareness-raising events, the provision of counseling services, and the development of policies to facilitate reporting of violence to campus officials. While these are important steps, literature on commuter students’ social experiences of college and connectedness11,10,12 suggests that meaningful prevention may need to be configured differently on urban commuter campuses than on residential campuses, with greater attention to the ways in which students connect to the campus community, especially early in their college experience.

One potentially promising tool is the Women Initiating New Goals for Safety (WINGS) intervention. WINGS is a computer-assisted set of activities with an audio component that screens for IPV, provides participants assistance in developing a safety plan and setting goals, while introducing them to available social services for their individual needs. WINGS is based on evidence showing that women are more likely to disclose IPV in an anonymous setting and provides the opportunity to collect data on IPV prevalence and service use.38 A program similar to WINGS, delivered with high visibility and accessibility, could serve as the basis for campus-wide IPV screening protocols that are incorporated into orientation activities and could inform ongoing awareness efforts and services provided on campus. This recommendation recognizes IPV as a public health problem that can be detected early to reduce harm and is informed by suggestions of various medical and advocacy organizations.39–42

In terms of public health research more broadly, developing reliable systems for collecting data on IPV warning signs and experiences among college students is critical, especially for institutions that may be serving higher risk populations.3 Given the pressing nature of IPV for college students, moving beyond institutional data collection to the collection of nationally representative population-level data assessing IPV among college students would be an even greater step forward and would require devoting ongoing funding to support this research over multiple years. Also essential is the fostering of collaborations between public health and education researchers to develop more up-to-date typologies of colleges and college students in terms of commuter student populations. As noted in the introduction to this paper, data that help us to understand different populations of commuter students who may be distinct in terms of social class are rare. If these data were more available, accessible, and representative, more meaningful multilevel analyses of off-campus social environments and IPV risk for commuter students would become possible.

Conclusion

Though the majority of students attending college in the USA commute to college from home, data on IPV risk during college centers on residential college students. Commuter college students living in urban areas may experience IPV-related risks that are distinct from those of residential college students as a result of their movement between on- and off-campus social environments. Furthermore, students experience a wide range of forms of violence, not just sexual assault, the focus of recent action on college campuses. While they were derived from a small sample, our data indicate that, for urban commuter students, college attendance itself can sometimes elevate risk of IPV when a partner seeks to limit and control their student partner’s experience of college and/or is threatened by what may be achieved by their partner through college attendance. In addition to formulating policies for addressing IPV, commuter colleges have the opportunity to mitigate these risks by developing more comprehensive screening and prevention activities. Such steps might not only reduce the prevalence and severity of IPV but also, by reducing the academic consequences of IPV described by our participants, could increase academic success and college completion. By making focused efforts to ensure that women at risk of IPV successfully complete their college degree, urban commuter campuses can increase the capacity of these women to reduce IPV risk and improve their health and well-being throughout their lifetimes.

Acknowledgments

Financial support for this project was provided by the Healthy CUNY Initiative at the City University of New York. The authors would like to thank Nick Freudenberg, Patti Lamberson, and the anonymous reviewers for helpful comments on earlier versions of this paper.

Footnotes

For instance, the City University of New York, the large institution studied in this paper, recently asked questions about physical and sexual assault in the last 12 months when conducting a survey of its students’ health experiences, but did not collect information about whether the perpetrator of the assault was an intimate partner. This is being remedied in an upcoming survey. The American College Health Association’s National College Health Assessment (http://www.acha-ncha.org/sample_survey.html), which is used voluntarily by some institutions, does include questions about emotional, physical, and sexual abuse by an intimate partner.

Currently, approximately 3,100 CUNY students live on campus out of a total student population of almost 270,000, which is just over 1 % of students.

As noted previously, the American College Health Association’s National College Health Assessment includes questions assessing the previous year incidence of three forms of IPV. However, the NCHA is a proprietary tool used voluntarily by select colleges, and resultant data is thus not representative of all college students (http://www.acha-ncha.org/partic_history.html). The National College Health Risk Behavior Survey, conducted by the Centers for Disease Control (CDC), appears to have gathered data from a representative sample of college students but, to our knowledge, has not been repeated since 1995 (http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/00049859.htm). In 2011, the CDC published data for the first time from its National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey (http://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/nisvs/summary_reports.html), though to our knowledge, the survey has yet to collect enough data to meaningfully examine college students as a subpopulation.

Contributor Information

Emma K. Tsui, Phone: 347-577-4038, Email: emma.tsui@lehman.cuny.edu

E. Karina Santamaria, Email: karina_santamaria@brown.edu.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Intimate Partner Violence: Definitions. 2014. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/intimatepartnerviolence/definitions.html. Accessed August 15, 2014.

- 2.Black MC, Basile KC, Breiding MJ, et al. The National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey (NISVS): 2010 Summary Report. Atlanta: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2011. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/pdf/nisvs_executive_summary-a.pdf. Accessed August 15, 2014.

- 3.Flake DF. Individual, family, and community risk markers for domestic violence in Peru. Violence Women. 2005;11(3):353–373. doi: 10.1177/1077801204272129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Straus M. Prevalence of violence against dating partners by male and female university students worldwide. Violence Women. 2004;10(7):790–811. doi: 10.1177/1077801204265552. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Caldwell JEWV, Swan SC. Gender differences in intimate partner violence outcomes. Psychol Violence. 2012;2(1):42–57. doi: 10.1037/a0026296. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Domestic Violence Resource Center. Domestic violence statistics. Available at: http://www.dvrc-or.org/dv-facts-stats/. Accessed August 15, 2014.

- 7.United States Department of Justice, Federal Bureau of Investigation. Crime in the United States, 2012.; 2013. Available at: http://www.fbi.gov/about-us/cjis/ucr/crime-in-the-u.s/2012/crime-in-the-u.s.-2012/offenses-known-to-law-enforcement/expanded-homicide/expanded_homicide_data_table_10_murder_circumstances_by_relationship_2012.xls. Accessed September 22, 2014.

- 8.Knowledge Networks. 2011 College Dating and Abuse Poll.; 2011. Available at: http://www.loveisrespect.org/pdf/College_Dating_And_Abuse_Final_Study.pdf. Accessed August 15, 2014.

- 9.Straight ES, Harper FW, Arias I. The impact of partner psychological abuse on health behaviors and health status in college women. J Interpers Violence. 2003;18(9):1035–1054. doi: 10.1177/0886260503254512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kuh GD, Gonyea RM, Palmer, Megan. The Disengaged Commuter Student: Fact or Fiction? Indiana University Center for Postsecondary Research and Planning; 2001. Available at: http://nsse.iub.edu/pdf/commuter.pdf. Accessed September 23, 2014.

- 11.Kuh GD, Kinzie J, Buckley JA, Bridges BK, Hayek JC. What Matters to Student Success: A Review of the Literature. Washington, D.C.: National Postsecondary Education Cooperative; 2006.

- 12.CUNY Office of Institutional Research and Assessment. Student Data Book. New York City: City University of New York; 2014. Available at: http://www.cuny.edu/irdatabook/rpts2_AY_current/ENRL_0001_UGGR_FTPT.rpt.pdf. Accessed September 22, 2014.

- 13.CUNY Office of Institutional Research and Assessment. Student Data Book. New York City: City University of New York; 2014. Available at: http://cuny.edu/about/administration/offices/ira/ir/data-book/current/student/ug_student_profile_f13.pdf. Accessed September 22, 2014.

- 14.New York City Department of Health & Mental Hygiene. Intimate Partner Violence Against Women in New York City.; 2008. Available at: http://www.nyc.gov/html/doh/downloads/pdf/public/ipv-08.pdf. Accessed August 15, 2014.

- 15.Raj A, Silverman J. Violence against immigrant women: the roles of culture, context, and legal immigrant status on intimate partner violence. Violence Women. 2002;8(3):367–398. doi: 10.1177/10778010222183107. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Frye V, Galea S, Tracy M, Bucciarelli A, Putnam S, Wilt S. The role of neighborhood environment and risk of intimate partner femicide in a large urban area. Am J Public Health. 2008;98(8):1473–1479. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.112813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McCarthy SK. Availability of emergency contraceptive pills at university and college student health centers. J Am Coll Health. 2002;51(1):15–22. doi: 10.1080/07448480209596323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McBride DR, Van Orman S, Wera C, Leino V. 2010 Survey on the Utilization of Student Health Services. American College Health Association Benchmarking Committee; 2010. Available at: http://www.acha.org/topics/docs/acha_benchmarking_report_2010_utilization_survey.pdf. Accessed September 22, 2014.

- 19.Freudenberg N, Manzo L, Mongiello L, Jones H, Boeri N, Lamberson P. Promoting the health of young adults in urban public universities: a case study from City University of New York. J Am Coll Health. 2013;61(7):422–430. doi: 10.1080/07448481.2013.823972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Likins JM. Research refutes a myth: commuter students do want to be involved. NASPA J. 1991;29(1):68–74. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Alfano H, Eduljee N. Differences in work, levels of involvement, and academic performance between residential and commuter students. Coll Stud J. 2013;47(2):334–342. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jacoby B. Why involve commuter students in learning? New Dir High Educ. 2000;2000(109):3–12. doi: 10.1002/he.10901. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bing VM. Addressing intimate partner violence on college campuses: strategies and opportunities. NYS Psychol. 2011;23(2):25–27. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Agoff C, Herrera C, Castro R. The weakness of family ties and their perpetuating effects on gender violence: a qualitative study in Mexico. Violence Women. 2007;13(11):1206–1220. doi: 10.1177/1077801207307800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Krug EG, Mercy JA, Dahlberg LL, Zwi AB. The world report on violence and health. Lancet. 2002;360(9339):1083–1088. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)11133-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Morris MW, Leung K, Ames D, Lickel B. Views from inside and outside: integrating emic and etic insights about culture and justice judgment. Acad Manag Rev. 1999;24(4):781–796. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lincoln YS, Guba EG. Naturalistic inquiry. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Patton M. Enhancing the quality and credibility of qualitative analysis. Health Serv Res. 1999;34(5):1189–1208. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Coutts A, Kawachi I. The urban social environment and its effects on health. In: Freudenberg N, Galea S, Vlahov D, editors. Cities and the health of the public. Nashville: Vanderbilt University Press; 2006. pp. 49–60. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Beyer K, Wallis AB, Hamberger LK. Neighborhood Environment and Intimate Partner Violence: A Systematic Review. Trauma Violence Abuse 2013:1524838013515758. doi:10.1177/1524838013515758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 31.Burke JG, O’Campo P, Peak GL. Neighborhood influences and intimate partner violence: does geographic setting matter? J Urban Health. 2006;83(2):182–194. doi: 10.1007/s11524-006-9031-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.O’Campo P, Gielen AC, Faden RR, Xue X, Kass N, Wang MC. Violence by male partners against women during the childbearing year: a contextual analysis. Am J Public Health. 1995;85(8 Pt 1):1092–1097. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.85.8_Pt_1.1092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Paulsen MB. St. John EP. Social class and college costs: examining the financial nexus between college choice and persistence. J High Educ. 2002;73(2):189–236. doi: 10.1353/jhe.2002.0023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gianoutsos D. Comparing the student profile characteristics between traditional residential and commuter students at a public, research-intensive, urban commuter university. 2011. Available at: http://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1926&context=thesesdissertations. Accessed August 15, 2014.

- 35.New York City Domestic Violence Fatality Review Committee Annual Report 2013. New York City: Mayor’s Office to Combat Domestic Violence; 2013. Available at: 21 http://www.nyc.gov/html/ocdv/downloads/pdf/Statistics_8th_Annual_Report_Fatality_Review_Committee_2013.pdf. Accessed August 15, 2014.

- 36.Malik S, Sorenson SB, Aneshensel CS. Community and dating violence among adolescents: perpetration and victimization. J Adolesc Health. 1997;21(5):291–302. doi: 10.1016/S1054-139X(97)00143-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Baum S, Ma J, Payea K. Education Pays 2013: The Benefits of Higher Education for Individuals and Society. New York City: College Board Advocacy and Policy Center; 2013. Available at: http://trends.collegeboard.org/sites/default/files/education-pays-2013-full-report.pdf. Accessed September 22, 2014.

- 38.Columbia School of Social Work. Grant Awarded to Develop Technology to Abate Intimate Partner Violence. 2011. Available at: http://socialwork.columbia.edu/news-events/grant-awarded-develop-technology-abate-intimate-partner-violence. Accessed August 15, 2014.

- 39.American College of Emergency Physicians. Domestic Family Violence. 2007. Available at: http://www.acep.org/Clinical---Practice-Management/Domestic-Family-Violence/. Accessed August 15, 2014.

- 40.American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Screening Tools - Domestic Violence. Available at: https://www.acog.org/About-ACOG/ACOG-Departments/Violence-Against-Women/Screening-Tools--Domestic-Violence. Accessed August 15, 2014.

- 41.American Academy of Family Physicians. Violence Position Paper. 2014. Available at: http://www.aafp.org/about/policies/all/violence.html. Accessed August 15, 2014.

- 42.Fullwood PC. Preventing Family Violence: Community Engagement Makes the Difference. San Francisco: Family Violence Prevention Fund; 2002. Available at: http://www.futureswithoutviolence.org/userfiles/file/ImmigrantWomen/PFV-Community%20Engagement.pdf. Accessed July 14, 2013.