Abstract

In Escherichia coli, the ratio of the two most abundant chemoreceptors, Tar/Tsr, has become the focus of much attention in bacterial taxis studies. This ratio has been shown to change under various growth conditions and to determine the response of the bacteria to the environment. Here, we present a study that makes a quantitative link between the ratio Tar/Tsr and the favored temperature of the cell in a temperature gradient and in various chemical environments. From the steady-state density-profile of bacteria with one dominant thermo-sensor, Tar or Tsr, we deduce the response function of each receptor to temperature changes. Using the response functions of both receptors, we determine the relationship between the favored temperature of wild-type bacteria with mixed clusters of receptors and the receptor ratio. Our model is based on the assumption that the behavior of a wild-type bacterium in a temperature gradient is determined by a linear combination of the independent responses of the two receptors, factored by the receptor’s relative abundance in the bacterium. This is confirmed by comparing our model predictions with measurements of the steady-state density-profile of several bacterial populations in a temperature gradient. Our results reveal that the density-profile of wild-type bacteria can be accurately described by measuring the distribution of the ratio Tar/Tsr in the population, which is then used to divide the population into groups with distinct Tar/Tsr values, whose behavior can be described in terms of independent Gaussian distributions. Each of these Gaussians is centered about the favored temperature of the subpopulation, which is determined by the receptor ratio, and has a width defined by the temperature-dependent speed and persistence time.

Introduction

Thermotaxis is critical for the survival of microorganisms, which lack internal mechanisms for regulating their cellular temperature. In addition, thermal cues can help microorganisms navigate their surroundings in search of specific targets (1–3). It has been suggested, for example, that mammalian sperm cells navigate toward the egg guided by ovulation-dependent temperature differences within the female genital tract (1). Similarly, bacteria follow thermal gradients to colonize certain regions, form biofilms, and infect host cells or tissues. An interesting aspect of thermotaxis is the precision sensing associated with the ability of many microorganisms to find a specific temperature in their environment. In the case of Escherichia coli, it was first established by Maeda et al. (4) that the bacteria accumulate at an intermediate temperature within a gradient. Subsequent experiments on bacterial thermotaxis identified the thermo-sensing properties of the receptors and the response regulation network (5–7).

Today we know that in E. coli, temperature, pH, and chemicals are detected by a shared set of five species of trans-membrane receptors (8,9). In wild-type (wt) bacteria, the response to temperature is dominated by the two most abundant receptors, Tar and Tsr (10). The response of each receptor to temperature depends on the receptor’s methylation level, which is affected by the temperature itself as well as the chemical environment (5–7,10). Tar is a heat-seeking receptor when nonmethylated but becomes cold-seeking with the methylation of a single residue (6). Tsr is a warmth-seeking receptor at low methylation levels, but becomes insensitive to temperature changes at high methylation levels. Thus, Tar in the presence of receptor-binding ligands, such as aspartate, maltose, or glutamate, and at elevated temperatures, is cold-seeking (5–7). On the other hand, Tsr in the presence of receptor-binding ligands such as serine and glycine, and at elevated temperatures, is insensitive to temperature changes (5,10). The methylation of each receptor is also influenced by the internal and external pH, which is itself affected by temperature, with increased methylation of Tsr at high pH and increased methylation of Tar at low pH (11,12).

The signals received through Tar and Tsr receptors are integrated by the bacteria to produce a single output in the form of increasing or decreasing the phosphorylation of the response regulator protein CheY, which regulates the flagellar motor switching frequency (13). Therefore, changes in the relative number of each type of receptor can change the response of the bacteria to their environment (10,12,14). Specifically with respect to temperature, we previously found that bacteria switch from heat-seeking to cold-seeking when grown above a critical concentration in batch mode (10). Our results show that the switch in the temperature response is initiated by the changes in the chemical environment and is later reinforced by a switch in the ratio Tar/Tsr, with Tar becoming more abundantly expressed than Tsr. While this study shows that the response of bacteria to a temperature gradient can be one of two opposing responses, the possibility of a gradual change in temperature response as a function of Tar/Tsr has not been tested. In addition, even though the response of different receptors to temperature has been qualitatively described, a quantitative understanding of the cell response to thermal changes and an accurate description of the cell behavior in a temperature gradient are still lacking. This is in part due to the fact that Tar and Tsr, like all other proteins in the cell, exhibit wide, inherent cell-to-cell variability. Because the favored temperature seems to be dependent on the ratio Tar/Tsr, we expect that it will be different for different cells or groups of cells within a population. This behavioral variability might play an important role in the population’s behavior and fitness in a temperature gradient, and it is important to characterize in order to understand bacterial thermotaxis quantitatively.

In this study, we use a simple two-state model of the receptors’ response to temperature to quantitatively explain the steady-state cell density-profile of mutant strains of bacteria lacking one of the two major thermosensing receptors, Tar or Tsr, in a temperature gradient. We estimate the maximum strength of each receptor’s response to temperature, and based on these measurements, we propose a model that determines the accumulation temperature of wt bacteria, with mixed receptors clusters. Our model assumes that the favored temperature of the cell is the temperature where the cell response switches from being Tsr-controlled (heat-seeking) to being Tar-controlled (cold-seeking). The model is validated by comparison to the experimentally measured accumulation temperature of wt bacterial populations with different average ratios of Tar/Tsr and in different chemical environments. We further show that the density-profile of wt bacteria in a temperature gradient is accurately described using the measured population variability of the ratio Tar/Tsr. The histogram of Tar/Tsr expression is used to quantify the fraction of cells belonging to subpopulations with distinct ratios, each of which is assigned an accumulation temperature in the gradient calculated by our model. Our results are consistent with the predictions of a theoretical model proposed by Jiang et al. (15), and provide, to our knowledge, the first quantitative measurements of the effect of the ratio Tar/Tsr and the chemical environment on the response of bacteria to temperature.

Materials and Methods

Bacterial strains and growth conditions

The wt E. coli strain RP437 was used to measure the response of the bacteria to a temperature gradient. The mutant strains RP2361 (Δtar) and HCB317 (Δtsr) were used to characterize the response in the absence of Tar and Tsr, respectively. All strains used in the response measurements were visualized by YFP fluorescence, which was expressed constitutively from a plasmid (pZA3R-YFP). The strains RPA1V2C, RPA1V, and RPA2C, which were derived from RP437 following the methods presented in Datsenko and Wanner (16), were used to measure the distributions of Tar and Tsr expression by flow cytometry. In RPA1V2C and RPA2C, the gene of the red fluorescent protein mcherry was inserted into the genome in place of tar. In RPA1V2C and RPA1V, the gene of the yellow fluorescent protein venus was inserted into the genome in place of tsr. The fluorescent reporters were placed under the control of the native promoters and ribosome-binding sites. In all experiments, bacterial cultures were launched from a frozen stock and grown overnight at 30°C in M9CG (M9 minimal medium supplemented with 1 g L−1 casamino acids and 4 g L−1 glucose) to optical density (OD) at 600 nm <0.1 (∼1.25 × 107 cells cm−3), corresponding to early exponential phase. It was diluted 1:100 into fresh M9CG the following morning, and was further grown under the same conditions to different ODs, as required.

Receptor copy number measurements and ratio calibration

Overnight bacterial cultures were grown and diluted as described above. Samples were harvested from the diluted cultures at different ODs, placed on ice for 5–10 min to reduce cell motility, and subsequently centrifuged for 5 min at 10,000 rpm. The supernatant was removed and the bacteria were suspended in fixing buffer (1.5% formaldehyde in 10 mM phosphate buffer, pH ∼7.4) at OD ∼0.6. The sample was incubated for 30 min at room temperature while mixing. The fixative was then removed by centrifugation, and the bacteria were washed and resuspended in 10 mM phosphate buffer (pH ∼7.4), and stored overnight at 4°C. Two-color fluorescence data was collected from all strains (RPA1V2C, RPA1V, and RPA2C) by flow cytometry from 100,000 cells in each sample. The fluorescence data of the two-color strain (RPA1V2C) was corrected by subtracting the background fluorescence obtained from the RPA1V strain (for red) and from the RPA2C strain (for yellow). This allowed us to correct for bacterial autofluorescence, as well as leakage between fluorescence channels.

In addition, using the one-step RT-PCR method described in Salman and Libchaber (10), we measured the ratio of the average amounts of mRNA expressed from both tar and tsr genes in RP437 bacteria grown under the same conditions detailed above. Our measurement of the average Tar mRNA divided by average Tsr mRNA (〈TarmRNA〉/〈TsrmRNA〉) at low OD yields a ratio of 0.551 ± 0.094, consistent with a previously published protein ratio of 0.562 (17). Therefore we used the mRNA ratio to calibrate our fluorescence measurements to the actual ratio of Tar/Tsr. For that purpose, the ratio 〈TarmRNA〉/〈TsrmRNA〉 was plotted as a function of 〈red〉/〈green〉 (each averaged across the population separately), and fitted to a linear function used afterward to calculate the ratio Tar/Tsr from the red/green data (Fig. S1 in the Supporting Material). The intercept of the fit is close to zero, which we expect because the background fluorescence has been removed. The slope represents a constant scaling, which accounts for the proportionality between protein and fluorescence intensity for each reporter construct. We are aware that there is a range of values for Tar and Tsr expression reported in the literature and that the expression level depends on growth medium and culture density. However, our analysis does not depend on the absolute number of receptors because the control parameter that determines the favored temperature is the receptor ratio, as we explain below. Thus, calibration of the ratio is sufficient for our analyses.

Measurements and image analysis of the response to temperature gradient

To test the thermotactic response as a function of optical density, bacterial samples were harvested at different ODs by centrifugation, resuspended in fresh M9CG or motility buffer (10 mM potassium phosphate, 10 mM sodium lactate, 0.1 mM EDTA, and 1 mM L-methionine, pH = 7.0) to OD ∼0.3, and incubated at room temperature for 30–40 min while mixing to allow the cells to adapt to the medium (5). To test the response as a function of glycine, the sample was washed once with motility buffer and stored in buffer at room temperature until testing to preserve cell motility and prevent further growth and expression of Tar and Tsr. Before each measurement, a fraction of the sample was removed from the buffer by centrifugation, resuspended at OD ∼0.3 in the testing medium with the desired glycine concentration, and incubated at room temperature for 30–40 min.

The response of bacteria to a temperature gradient was measured in thin PDMS channels adhered to a microscope slide. The temperature gradient was applied using an infrared laser (λ = 1480 nm) focused with a 32× objective into the channel through the glass slide, and the bacteria were observed with a 10× objective, on an inverted microscope (Axiovert 40 CFL; Carl Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany) as described previously (10,18). For each sample, three movies were recorded for 3 min after applying the temperature gradient at 1/5 frame/second rate, at different locations within the channels. The temperature profile was estimated from images of temperature-sensitive dye, BCECF, as described in Braun and Libchaber (19) and Fig. S2.

Analysis was carried out using the software IMAGEJ (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD) and a custom MATLAB program (The MathWorks, Natick, MA). The first frame from each movie was subtracted from all other frames to remove background fluorescence. The average intensity of the second frame was used to normalize the fluorescence values of the remaining frames. That is, the accumulation of bacteria (increase in fluorescence) was normalized to the background concentration of bacteria. Other normalizations were done as described in the text and figures. The steady-state profile of the bacteria in the temperature gradients was extracted by averaging the images of the last 30 s of the three movies.

Results

Temperature-dependent activity of Tsr

To determine the activity (heat-seeking or insensitive) of Tsr as a function of temperature, we tested the behavior of the mutant strain RP2361, which lacks Tar (Δtar), in a temperature gradient. The response of these bacteria is determined primarily by Tsr, and their density-profile in a temperature gradient can essentially be described by a Fokker-Planck-type equation (18). Changes in the bacterial density-profile as a function of time result from both the response of the single receptor species to temperature changes, which drive the bacteria along the temperature gradient, and the flux of the bacteria due to spatial changes in their concentration:

| (1) |

Here, n(t,x) is the density of the bacteria, D is the effective diffusion coefficient of the bacteria resulting from their random walk motion, and T(x) is the temperature profile. The parameter k describes the strength and sign of the response to an increase in temperature, where henceforth ks refers to the strength of Tsr response, and ka refers to the strength of Tar response. For Tsr it has been demonstrated that k switches from heat-seeking (ks > 0) to insensitive (ks = 0) as a function of its methylation level (5,6) and that the methylation level changes with temperature, ligand concentration, and pH (5,7,11,12). However, rather than model the methylation level of the receptors, we directly link the state of the receptor to the temperature in the following manner: we assume that the probability of each receptor to be in one of two states depends on the temperature-dependent free energy, G(T), associated with that state, similar to the model of Jiang et al. (15). Using a first-order approximation to describe the free energy, the probability of the receptor to be in a heat-seeking state can be expressed by

| (2) |

The form of the exponent in Eq. 2 results from a linear expansion of ΔG(T)/kBT around T0, where ΔG(T0) = 0. Qualitatively, T0 can be considered the switching temperature and Ts the steepness of the switch. In principal, T0 and Ts can depend on the chemical environment and on the concentration of ligands associated with the receptor, which would indicate coupling between temperature and the chemical signals received by the receptors.

From Eq. 2, k(T) for Tsr can be written as

| (3) |

where kh > 0 in units of μm2⋅s−1⋅°C−1 describes the maximum strength of the response to temperature in the heat-seeking state.

The steady-state solution to Eq. 1 (with ks of the form given by Eq. 3) is given by

| (4) |

where the nb and Tb values are the background cell-density and temperature, respectively. Equation 4 describes well the experimental density profiles of the Δtar strain (Fig. 1). Fitting Eq. 4 to our bacterial density-profiles yields estimates for the parameters T0 and Ts in units of °C and kh/D in units of °C−1 (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

The response of mutant strains RP2361 (Δtar) and HCB317 (Δtsr) to a temperature gradient. (A) RP2361 (Δtar) bacteria are heat-seeking below ∼30°C above which temperature they become insensitive to temperature changes (solid circles, left y axis). (Solid line) Fit of the model (Eq. 4), which yields the following parameters: T0 = 30.5 ± 0.5°C, Ts = 2.5 ± 0.2°C, and kh/D = 0.58 ± 0.04°C−1. In nutrient-rich medium, HCB317 (Δtsr) bacteria are cold-seeking below ∼37°C above which temperature they also become insensitive to temperature changes (open circles, right y axis). (Dashed line) Fit of the model (Eq. 4), yielding the following parameters for the switching behavior of Tar used in subsequent analyses: T0 = 36.4 ± 0.9°C, Ts = 1.8 ± 1.3°C, and kh/D = −0.11 × 0.01°C−1. Each experimental density-profile is the average of three biological replicates. (B) The level of RP2361 (Δtar) accumulation is reduced with added glycine. (Solid circles) Bacteria in M9CG, which contains 0.1 mM glycine. (Decreasing levels of shading) 2, 4, and 10 mM additional glycine. The responses are scaled by the maximum value of the accumulation in M9CG. (C) Adding glycine to the medium reduces the maximum response of Tsr to temperature by reducing the magnitude of kh. (Solid line) Hill function of the form used in Sourjik and Berg (24) with a Hill coefficient of 6. The Hill function fit value at 0.1 mM glycine: kh/D = 0.56 ± 0.06°C−1, which corresponds to M9CG medium, is used to describe the switching behavior of Tsr in subsequent analyses. (D) The model parameter Ts is also reduced with the addition of glycine to the medium (open squares and solid line to guide the eye, right y axis). However, T0 (solid squares, left y axis) appears to be independent of Tsr ligands with a mean over glycine concentrations of 29.7 ± 0.4°C (light shaded line), which is used to describe the switching behavior of Tsr in subsequent analyses. Error bars in (A) and (B) represent SD of the binned data. (C and D) Error bars represent the 95% confidence interval of the parameter estimates. Note that the data for RP2361 (Δtar) in M9CG is from different sets of experiments in (A) and (B)–(D). However, the parameter estimates from each experiment fall within the same error range. To see this figure in color, go online.

Previous studies have shown that both the cell’s swimming speed and persistence time change as a function of OD (20) and temperature (20–23), which does affect the effective diffusion coefficient of the bacteria D, and the strength of their attraction to heat kh. However, the new parameter kh/D, representing the response function normalized by the effective diffusion coefficient, does not depend on the characteristics of the cellular motion, such as speed and persistence time as is evident from its units. This implies that the change in the motility due to temperature and/or OD should not play a role in determining the bacterial favored temperature.

Our parameter estimations carried out in this manner indicate that Tsr remains heating-seeking below a critical temperature (∼30°C in rich medium and ∼33°C in motility buffer with no nutrients added), above which the receptor becomes insensitive to temperature changes (Figs. 1 and S3). It is important to note here that the magnitudes of kh/D and Ts are also different in medium compared to motility buffer (Figs. 1 and S3). These differences in the values of T0, Ts, and kh/D, are likely due to physiological changes in the bacteria in the presence of nutrients (21). The density-profile of the Δtar strain in M9CG is well described by the response function given in Eq. 3, with the following parameters: T0 = 30.5 ± 0.5°C, Ts = 2.5 ± 0.2°C, and kh/D = 0.58 ± 0.04°C−1 (Fig. 1 A).

Further tests of the Δtar strain in the M9CG medium supplemented with additional glycine demonstrate that the qualitative response of Tsr as a function of temperature does not change when the concentration of receptor-binding ligand in the medium is increased, i.e., it switches from heat-seeking to insensitive with increasing temperature (Fig. 1 B). However, our results indicate that kh/D and Ts change quantitatively as a function of the glycine concentration (Fig. 1, C and D). The behavior of kh/D as a function of glycine in both M9CG (Fig. 1 C) and motility buffer (Fig. S3) can be described by a Hill function with a Hill coefficient of h = 6 (24) similar to the reduction of the chemotactic response at increasing levels of ligands described in previous studies of chemotaxis, presumed to be due to the degree of cooperativity of the receptors as determined by their cluster size (24,25). The reduction of kh/D is attributed to an increase in the methylation level of Tsr due to the increase in the background glycine concentration, which reduces the fraction of heat-seeking receptors in the cell. This result is consistent with immunoblotting experiments, which show that increasing ligand concentration gradually increases the number of highly methylated receptors while maintaining a large fraction of the receptors unmethylated (12). In addition, we also find that an increase in glycine levels increases the rate at which the activity of Tsr decreases to zero near the critical temperature, i.e., Ts decreases with increasing glycine concentration (Fig. 1 D). Nonetheless, the receptors that remain heat-seeking maintain their activity up to the same critical temperature, i.e., T0 is independent of ligand concentration (Fig. 1 D). These experiments are equivalent to synthetically reducing the copy number of Tsr receptors in the cell without changing the copy number of Tar. This is expected to shift the accumulation temperature of the bacteria toward lower temperature, as we demonstrate below.

Temperature-dependent activity of Tar

The activity of Tar as a function of temperature was determined using the mutant strain HCB317, which lacks Tsr (Δtsr), in a manner similar to that described in the previous section. The response of these bacteria is determined primarily by Tar, and their steady-state density-profile in a temperature gradient can also be described by Eq. 1, albeit with a different response function ka(T). Tar has been shown to switch from heating-seeking (ka > 0) to cold-seeking (ka < 0) upon methylation of one of its methyl-accepting sites (6). In a rich medium, however, Tar is always cold-seeking. Therefore, in M9CG we initially set the response function ka(T) in Eq. 1 to be constant, ka(T) = kh < 0. Fitting the measured steady-state cell density-profile to Eq. 4 with an escape response that is independent of temperature, we do not capture the bacterial density-profile over the full range of temperature. Instead, we find that the density-profile of the Δtsr strain is best described by a response function in which Tar is cold-seeking at low temperature and insensitive at very high temperature, which, similar to the response of Tsr, can be described by Eq. 3, with the following parameters: T0 = 36.4 ± 0.9°C, Ts = 1.8 ± 1.3°C, and kh/D = −0.11 ± 0.01°C−1 (Fig. 1 A). The cold-seeking behavior of Tar results from the fact that the receptor is easily methylated in the presence of high concentrations of its primary ligand, aspartate, in the medium used here (5,6,10). The insensitivity of Tar to temperature changes at high temperature has not been reported before. However, because this switch occurs at temperatures higher than ∼37°C, it could be the result of other physiological changes within the cell due to high temperature. In motility buffer, on the other hand, the steady-state density profile of the Δtsr strain in the temperature gradient is well described using a response function that switches from heat-seeking to cold-seeking. The results presented in Fig. S3 show that the switch to a negative response appears above ∼37°C, as in the case of rich medium. The strength of the negative response, however, is nearly zero, kh/D = −1.8 × 10−3 ± 1.6 × 10−3°C−1, indicating that Tar might not exhibit a negative response in a medium lacking nutrients at all. Alternatively, because the switch occurs at a temperature above ∼37°C in such a medium, the response might be low due to the physiological state of the cell at these temperatures.

The response of wild-type bacteria to a temperature gradient

In a medium lacking nutrients, Tar and Tsr exhibit a positive (heat-seeking) response to temperature increases when the background temperature is <30°C. A rise in the background temperature increases the methylation state of both receptors. As a result, Tsr becomes insensitive to temperature changes, and Tar exhibits a negative (cold-seeking) response to increasing temperature. Because, the state of Tsr switches at a lower temperature than Tar, the temperature at which wt bacteria will inverse their response is determined by the Tar switch. This has been demonstrated experimentally by Paster and Ryu (7) and explained theoretically by Jiang et al. (15). Consequently, in this context, a change in the relative expression levels of the receptors does not affect the behavior of bacteria in a temperature gradient (Fig. S4).

However, in a rich medium, Tar is cold-seeking already at temperatures <30°C, as demonstrated in Fig. 1 A (see also Salman and Libchaber (10)), and the bacteria receive conflicting signals from Tar and Tsr. The strength of each signal depends on the relative copy number of the mediating receptor, and therefore, it is expected that the bacteria’s favored temperature will change with the ratio Tar/Tsr.

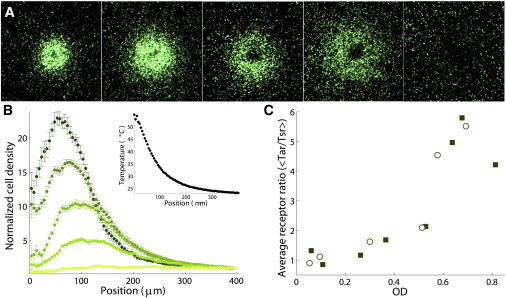

In an earlier study, we showed that the ratio of the average Tar copy number to the average Tsr copy number (〈Tar〉/〈Tsr〉) changes as the bacteria grow denser in batch culture. This change causes the bacteria to switch from favoring heat to favoring cold when subjected to a temperature gradient between 18°C and 30°C (10). Here, by increasing the temperature gradient to range from 23°C to 50°C, we observe that 1) the bacterial accumulation temperature decreases gradually (Fig. 2, A and B) rather than exhibiting a sharp switch from heat-seeking to cold-seeking and 2) the accumulation temperature decreases with the increase of the average ratio of Tar/Tsr (Fig. 2 C).

Figure 2.

Change in the bacteria’s accumulation temperature with culture density in batch mode. (A) In a temperature gradient, the bacterial accumulation moves toward lower temperatures with increasing culture density (OD from left to right, 0.08, 0.12, 0.18, 0.43, and 0.55). The images are taken 3 min after the temperature gradient is applied with the minimum and maximum intensity of each image adjusted to the range of the leftmost image. (B) Steady-state density-profiles of the samples in (A). Error bars indicate the 30-s time-averaged SD at each radial position. (Inset) Applied temperature gradient. (C) The increase in the ratio 〈Tar/Tsr〉 (circles and squares correspond to two different measurements) is proportional to the increase in the culture density. Note that this measurement is different from previously published measurements of the ratio of average Tar to average Tsr (〈Tar〉/〈Tsr〉) due to the strong correlation between the expression of both receptors (see Fig. S5). To see this figure in color, go online.

When a bacterium receives two conflicting signals, the favored temperature is expected to be the point at which these signals balance each other, as in the mechanism recently reported for pH sensing (12,26). Nevertheless, quantitative description of the bacterial temperature sensing is not trivial. As a result of the natural variability in protein expression within a population, each bacterium is expected to have a distinct number of Tar and Tsr receptors. If indeed the favored temperature is determined by the balance between the Tsr and Tar signals, then the favored temperature will be different from cell to cell. Therefore, at the level of the population, the temperature of the peak accumulation will correspond to the most abundant ratio of Tar to Tsr, which is different from 〈Tar〉/〈Tsr〉 due to strong correlation between the expression levels of Tar and Tsr (Fig. S5). This can complicate the determination of the population density-profile, because it will not be due to accumulation around one temperature with a spread caused by their density gradient, as in the case of a single receptor species. To address this problem, it is therefore required to measure the variability in Tar/Tsr and to determine the favored temperature for each ratio, separately.

In the following sections, we propose a model to describe the observed population density-profile in a temperature gradient and describe how it changes with the Tar/Tsr expression distribution. We verify our model by comparison to experimental data.

The bacterial favored temperature and the receptors’ ratio Tar/Tsr

After determining the individual response of each of the receptors, Tar and Tsr, to temperature and the influence of the chemical environment on their response, we turn to characterizing the behavior of the wt bacteria with clusters of mixed receptors. In wt bacteria, the relative strength of the signal from each receptor type can be defined as the receptor’s relative abundance, na,s/N (where na and ns are the numbers of Tar and Tsr receptors, respectively, and N is the total number of Tar and Tsr receptors in the cell), multiplied by the response strength of an individual receptor, ka,s(T, [L]), where [L] is the ligand concentration:

| (5) |

Note that the relative abundance was not considered in the single receptor species because it is “1” in that case. In a nutrient-free environment, the favored temperature should not change with the ratio of Tar/Tsr as discussed earlier (see also Fig. S4). In a nutrient-rich medium, such as M9CG, Tar has a negative response already at temperatures <30°C. This in turn introduces a competition between the two receptor species, and the expression levels of Tar and Tsr in each bacterium are expected to become an important factor in determining its favored temperature. This temperature is where the response function k(T) is equal to zero (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Bacteria are predicted to accumulate at the balance point between opposing responses from Tar and Tsr. The favored temperature of bacteria containing mixed receptor clusters can be predicted to occur at the temperature at which the magnitude of the opposing responses of Tar and Tsr balance, i.e., the zero-crossing (solid lines indicated by the open circles, which are the sums of various combinations of Tar and Tsr responses). Increasing the ratio Tar/Tsr from 0.5 to 2 by increasing the relative number of Tar (dotted light shading to dotted darker line) with Tsr fixed (dashed dark line) causes the total response function to change (light to dark shading), and as a result the accumulation point shifts from 34.6°C to 30.6°C (solid arrow). Likewise, for a fixed ratio of 0.5, reducing the response of Tsr with added glycine (dashed dark to dashed shaded line) changes the total response function (solid light shaded to solid medium shaded line), and shifts the accumulation point from 34.6°C to 32.8°C (shaded arrow). The magnitude of ka(T) was calculated using the parameters given in Fig. 1A. The magnitude of ks(T) was calculated using the parameters given in Fig. 1, C and D, for M9CG and M9CG + 1 mM glycine. To see this figure in color, go online.

At the temperature Tf where k(Tf) = 0, the response of the bacteria switches from being heat-seeking for T < Tf to being cold-seeking for T > Tf. As a result, the bacteria will accumulate at Tf. Setting the left-hand side of Eq. 5 to zero and solving for na/ns reveals that the ratio of the receptors, rather than their absolute number, determines the favored temperature. That is, for each ratio na/ns, there is a value of Tf, which satisfies

In addition, the maximum strength of Tsr attraction, (ns/N)kh,s, can be altered by changing the relative abundance of Tsr receptors or by changing kh through the addition of Tsr-binding ligands, which increases the methylation state of Tsr receptors causing more receptors to be inactive. On the other hand, in medium the maximum strength of Tar repulsion, (na/N)kh,a, can be altered only by changing the relative abundance of Tar receptors.

To test these predictions, we measured the distribution of wt E. coli bacteria with different relative levels of Tar and Tsr in a temperature gradient (Fig. 4 A). Different average ratios were obtained by allowing the bacteria to grow to different densities in batch mode (Fig. 2 C). Note that the effect of cell density on the cell motility, which has been characterized previously (20), does not play a role in determining the favored temperature because the dependence of both ks and ka on the motility characteristics is the same and the favored temperature is determined by their ratio:

However, making a link between the ratio Tar/Tsr and the favored temperature of the bacteria is confounded by the wide variability in the expression of Tar, Tsr, and Tar/Tsr across the population, revealed by single-cell measurements described in Materials and Methods (Fig. 4 B).

Figure 4.

The shift of bacterial favored temperature with increasing ratio Tar/Tsr. (A) The three accumulation profiles shown in Fig. 2, A and B, are plotted as a function of temperature and normalized between 0 at the background and 1 at the peak (dashed lines). (B) Increasing OD corresponds to increasing the ratio Tar/Tsr. The most abundant ratio is indicated (dashed lines). The Tar/Tsr distributions correspond to wt bacteria grown to the following ODs: 0.05 (light-shaded circles), 0.30 (medium-shaded squares), and 0.51 (solid triangles). (Solid lines) Drawn to guide the eye. To see this figure in color, go online.

To circumvent this problem, we used the measured distribution of Tar/Tsr to correlate the peak of the bacterial cell density-profile in the temperature gradient to the most abundant ratio Tar/Tsr. This correlation is more accurate if made between the statistical modes of Tar/Tsr distribution and the cell density-profile rather than the population average, which in this case depends also on the temperature profile as well as the bacterial density-profile.

We find that in a nutrient-rich environment, the accumulation temperature of the bacteria as a function of Tar/Tsr tested over several experiments falls onto a single curve that is well described by the theoretical calculation presented above (Fig. 5 A). Our theoretical calculation describes as well the effect of glycine on the favored temperature. As explained above (see Fig. 3), adding glycine to the medium reduces kh,s and Ts and changes the point at which |naka(T)| = |nsks(T, [L])|, as depicted in the inset of Fig. 5 A.

Figure 5.

Comparison between theoretical predictions and experiments. (A) The peak of wt bacteria with different ratios of Tar/Tsr follows the curve predicted by the balance between the response of the two receptors in M9CG, i.e., where na/ns= |ks(T, [L])/ka(T)|. The error in the ratio corresponds to the error in OD determined from the spectrophotometer to be ±0.05. As shown in Fig. 2C, the ratio increases sharply around OD = 0.6, resulting in the large error in the determination of the ratio in these populations. The error in temperature corresponds to the width of the peak in the gradient. (Inset) Theoretical curve for M9CG (solid line), M9CG + 1.4 mM glycine (dashed medium shaded line), and, M9CG + 4 mM glycine (dotted light shaded line). The points correspond to the accumulation of bacteria (OD = 0.1) in M9CG (solid circle), M9CG + 1.4 mM glycine (medium shaded circle), and M9CG + 4 mM glycine (light shaded circle). (B) The distribution of wt bacteria in the gradient can be described by placing distinct populations within the gradient based on the Tar/Tsr of that subpopulation and allowing those bacteria to diffuse around that temperature. Comparison between data and theory (solid lines) are shown for bacteria populations in Figs. 2 and 4 for ODs: 0.08 (light shaded circles), 0.43 (medium shaded squares), and 0.55 (solid triangles). The data are scaled between 0 and 1 to show the shift in the peak (light and medium shading) and the escape response (solid). Error bars represent SD of the binned data. To see this figure in color, go online.

Variability in the ratio Tar/Tsr and the population distribution in a temperature gradient

The shift in favored temperature due to changes in Tar/Tsr implies that cells expressing different relative levels of Tar and Tsr will favor different locations in the same gradient. Thus, when a population of bacteria is subjected to a temperature gradient, its density-profile along the gradient should in fact reflect the distribution of the expression ratio Tar/Tsr. To test this hypothesis, we used the distribution of Tar/Tsr measured earlier. This distribution was binned according to Tar/Tsr and each bin was assigned a favored temperature with steps of 1°C according to the graph in Fig. 5 A (see the Supporting Material for details). The location of each temperature (and thus the bacterial subpopulation that favors that temperature) was calculated from the temperature profile. Each subpopulation, however, was allowed to diffuse around their favored temperature producing a local Gaussian distribution about that location. The width of each Gaussian, σ, was assigned the value 2Dt, as is the case for diffusion in one dimension, with D = v2τ and t = τ, where v is the bacterial swimming speed and τ is the persistence time of the bacteria. Both v and τ have been measured in a previous work (21) and were found to be temperature-dependent (Fig. S6). The final density-profile of the bacterial population in the temperature gradient was then calculated by summing all the Gaussian distributions. These calculations for three different populations, with distinct Tar/Tsr distributions, are presented in Fig. 5 B together with the measured bacterial profile for populations with similar Tar/Tsr distributions. Our calculations exhibit substantial agreement with the measurements, providing further verification of our model.

Discussion

In this study, we provide a quantitative description of the correlation between the ratio of the sensing receptors Tar/Tsr and the bacterial favored temperature in a nutrient-rich environment. By measuring the response to temperature of bacteria lacking one of these two receptors, we measure the response function of the other receptor to temperature. Our results show that in a nutrient-rich environment, the response function of Tsr is positive (reduces the switching events frequency of the flagellar motor in response to increase in the temperature, i.e., it is heat-seeking) until ∼30°C, after which it decays to zero (no change in the flagellar motor switching frequency in response to temperature changes) over a range of ∼2°C. The response function of Tar is similar to that of Tsr; however, it starts as negative in the low temperature regime (reduces the frequency of switching events of the flagellar motor in response to decreases in the temperature, i.e., it is cold-seeking), and decays to zero for temperatures higher than ∼37°C, presumably due to the effect of high temperature on the physiological state of the bacterial cell as a whole. Based on these measurements, we estimate the relative strength of each receptor species to temperature changes, which we find to be fivefold greater for Tsr than it is for Tar in the active regime (|kh,s/kh,a| = |0.56/−0.11| = 5.1). We also propose a model that links Tar/Tsr to the favored temperature of wt bacteria with both receptor species.

Our model predicts that the favored temperature for each bacterium is the temperature where the response of the bacterium switches from being Tsr-controlled to being Tar-controlled. These results are confirmed by our experimental measurements of the favored temperature for several bacterial populations with different average Tar/Tsr. Our model also describes well the steady-state density-profile of a wt bacterial population in a temperature gradient. This is achieved by dividing the bacterial population into subgroups according to their Tar/Tsr and allowing each subgroup to diffuse around its favored temperature. The diffusion range, however, is also temperature-dependent due to the effect of temperature on the swimming speed and persistence time.

Furthermore, we have tested the effect of attractants that interact with one of the receptors on the overall behavior of the bacteria. We find that in nutrient-rich environments, Tsr attractants such as glycine alter the favored temperature of the bacteria. Glycine increases the methylation level of Tsr and, therefore, changes its response function to temperature variations. Our results show that the effect of glycine appears in the response function of Tsr in two ways. The first is by reducing the number of active receptors and, therefore, the relative fraction of heat-seeking receptors in the bacteria. The second is by decreasing the range of temperature (Ts) over which the Tsr activity decays to zero around the critical temperature (T0). Both of these effects lead to a decrease in the favored temperature of bacteria, as predicted previously (15).

In summary, we have previously shown that the ratio of Tar/Tsr determines the direction of bacterial migration in a temperature gradient (10), and later theoretical works have described possible mechanisms of precision sensing of temperature as well as pH in bacteria (15,26,27). The results presented here stand in good agreement with, and extend, these studies. It is important to note, though, that while the shift in the pH preference has also been explained by changes in the ratio Tar/Tsr (12,26), the response of the bacteria to temperature is the opposite of that to pH. That is, as the ratio Tar/Tsr increases, bacteria move toward colder temperatures corresponding to regions of higher external pH (21), whereas Yang and Sourjik (12) found that increasing Tar/Tsr shifts the inversion point of the pH response to lower values. This is clear evidence that the temperature-sensing mechanism in these receptors is independent of pH sensing and possibly competes with pH sensing. Further investigation would be required to determine the coupling and competition mechanisms between the two.

Finally, the expression of the motility genes in bacteria is highly regulated to suit the environment (28). Upregulation of motility is a stress response under a wide range of conditions, including nutrient depletion in batch mode culture (29). The tar and tsr genes are part of the flagellar regulon (30), and their expression also changes in response to the environment. Interesting questions, however, remain concerning the mechanism of the differential regulation of the two receptors, which traditionally have been placed in the same class within the flagellar regulon. It is known that tar exists within the meche operon, which contains the che genes, while tsr exists at an independent locus, which may contribute to the differences in expression (28,30). Thus, changes in motility are also accompanied by changes in the signal detection properties of the bacteria, which affect the behavior of the bacteria in a temperature gradient. One of these effects, as we demonstrate in this work, is allowing the bacteria to shift their accumulation temperature gradually toward lower temperature. The exact mechanism and possible benefits of such change in the expression level of the different genes and the resulting behavior remain speculative. However, the wide variability we observe in the ratio Tar/Tsr might contribute to the bacterial fitness by allowing them to disperse in a temperature gradient in order to reduce competition for resources. In addition, the sensitivity of this variability to the environment suggests that attention should be paid to this important factor in future studies of bacterial sensing.

Acknowledgments

We thank Mahmut Demir for his help with the temperature gradient experiments and the BCECF calibration.

Supporting Material

References

- 1.Bahat A., Eisenbach M. Sperm thermotaxis. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2006;252:115–119. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2006.03.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Poff K.L., Skokut M. Thermotaxis by pseudoplasmodia of Dictyostelium discoideum. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1977;74:2007–2010. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.5.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kessler J.O., Jarvik L.F., Matsuyama S.S. Thermotaxis, chemotaxis and age. Age (Omaha) 1979;2:5–11. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Maeda K., Imae Y., Oosawa F. Effect of temperature on motility and chemotaxis of Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 1976;127:1039–1046. doi: 10.1128/jb.127.3.1039-1046.1976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mizuno T., Imae Y. Conditional inversion of the thermoresponse in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 1984;159:360–367. doi: 10.1128/jb.159.1.360-367.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nishiyama S.I., Umemura T., Kawagishi I. Conversion of a bacterial warm sensor to a cold sensor by methylation of a single residue in the presence of an attractant. Mol. Microbiol. 1999;32:357–365. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01355.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Paster E., Ryu W.S. The thermal impulse response of Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:5373–5377. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0709903105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Berg H.C. Springer; New York: 2003. E. coli in Motion. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Imae Y. Molecular mechanism of thermosensing in bacteria. In: Eisenbach M., Balaban M., editors. Sensing and Response in Microorganisms. Elsevier Science; New York: 1985. pp. 73–81. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Salman H., Libchaber A. A concentration-dependent switch in the bacterial response to temperature. Nat. Cell Biol. 2007;9:1098–1100. doi: 10.1038/ncb1632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Krikos A., Conley M.P., Simon M.I. Chimeric chemosensory transducers of Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1985;82:1326–1330. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.5.1326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yang Y., Sourjik V. Opposite responses by different chemoreceptors set a tunable preference point in Escherichia coli pH taxis. Mol. Microbiol. 2012;86:1482–1489. doi: 10.1111/mmi.12070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Khan S., Spudich J.L., Trentham D.R. Chemotactic signal integration in bacteria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1995;92:9757–9761. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.21.9757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kalinin Y., Neumann S., Wu M. Responses of Escherichia coli bacteria to two opposing chemoattractant gradients depend on the chemoreceptor ratio. J. Bacteriol. 2010;192:1796–1800. doi: 10.1128/JB.01507-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jiang L., Ouyang Q., Tu Y. A mechanism for precision-sensing via a gradient-sensing pathway: a model of Escherichia coli thermotaxis. Biophys. J. 2009;97:74–82. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2009.04.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Datsenko K.A., Wanner B.L. One-step inactivation of chromosomal genes in Escherichia coli K-12 using PCR products. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2000;97:6640–6645. doi: 10.1073/pnas.120163297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stewart R.C., Dahlquist F.W. Molecular components of bacterial chemotaxis. Chem. Rev. 1987;87:997–1025. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Salman H., Zilman A., Libchaber A. Solitary modes of bacterial culture in a temperature gradient. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2006;97:118101. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.97.118101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Braun D., Libchaber A. Trapping of DNA by thermophoretic depletion and convection. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2002;89:188103. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.89.188103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Staropoli J.F., Alon U. Computerized analysis of chemotaxis at different stages of bacterial growth. EMBO J. 2000;78:513–519. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(00)76613-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Demir M., Salman H. Bacterial thermotaxis by speed modulation. Biophys. J. 2012;103:1683–1690. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2012.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Oleksiuk O., Jakovljevic V., Kollmann M. Thermal robustness of signaling in bacterial chemotaxis. Cell. 2012;145:312–321. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.03.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Demir M., Douarche C., Salman H. Effects of population density and chemical environment on the behavior of Escherichia coli in shallow temperature gradients. Phys. Biol. 2011;8:063001. doi: 10.1088/1478-3975/8/6/063001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sourjik V., Berg H.C. Functional interactions between receptors in bacterial chemotaxis. Nature. 2004;428:437–441. doi: 10.1038/nature02406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mello B.A., Tu Y. An allosteric model for heterogeneous receptor complexes: understanding bacterial chemotaxis responses to multiple stimuli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:17354–17359. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506961102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hu B., Tu Y. Precision sensing by two opposing gradient sensors: how does Escherichia coli find its preferred pH level? Biophys. J. 2013;105:276–285. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2013.04.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hu B., Tu Y. Behaviors and strategies of bacterial navigation in chemical and nonchemical gradients. PLOS Comput. Biol. 2014;10:e1003672. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1003672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chilcott G.S., Hughes K.T. Coupling of flagellar gene expression to flagellar assembly in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium and Escherichia coli. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2000;64:694–708. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.64.4.694-708.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Amsler C.D., Cho M., Matsumura P. Multiple factors underlying the maximum motility of Escherichia coli as cultures enter post-exponential growth. J. Bacteriol. 1993;175:6247–6255. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.19.6238-6244.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Macnab R.M. Genetics and biogenesis of bacterial flagella. Annu. Rev. Genet. 2003;26:131–158. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ge.26.120192.001023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.