Summary:

Fournier’s gangrene is a rapidly progressing necrotizing fasciitis, involving perineal, perianal, or genital regions, and it constitutes a true surgical emergency. Surgical excision of all necrotic tissue is required, and multiple debridements may be necessary to remove all nonviable tissue. After surgical intervention for debridement, reconstruction may be necessary. We present our experience in the treatment of tissue loss after Fournier’s gangrene of genital and perianal regions with the use of biological mesh (derma porcine mesh) in association with vacuum-assisted closure therapy.

Fournier’s gangrene (FG) is a rapidly progressing necrotizing fasciitis, involving perineal, perianal, or genital regions, with a potentially high mortality rate ranging from 15% to 50%.1–5 FG often results in tissue loss. After surgical intervention for debridement, reconstruction may be necessary.6–10 We describe our experience in reconstructive surgery for FG.

CASE REPORT

A 64-year-old male patient was admitted to the emergency department because of a 2-week history of high fever (body temperature, 39.5°C), perirectal pain, purulent drainage, and a clinical picture of bacterial sepsis and severe shock. He had undergone elastic ligature of hemorrhoidal nodules 20 days before. In his acute clinical status, we found perineal necrosis with exposition of rectum and scrotum necrosis with bilateral exposition of testicles. The inguinal region of the patient presented erythema and crepitations. His laboratory blood values showed signs of systemic inflammatory response syndrome. The patient was febrile.

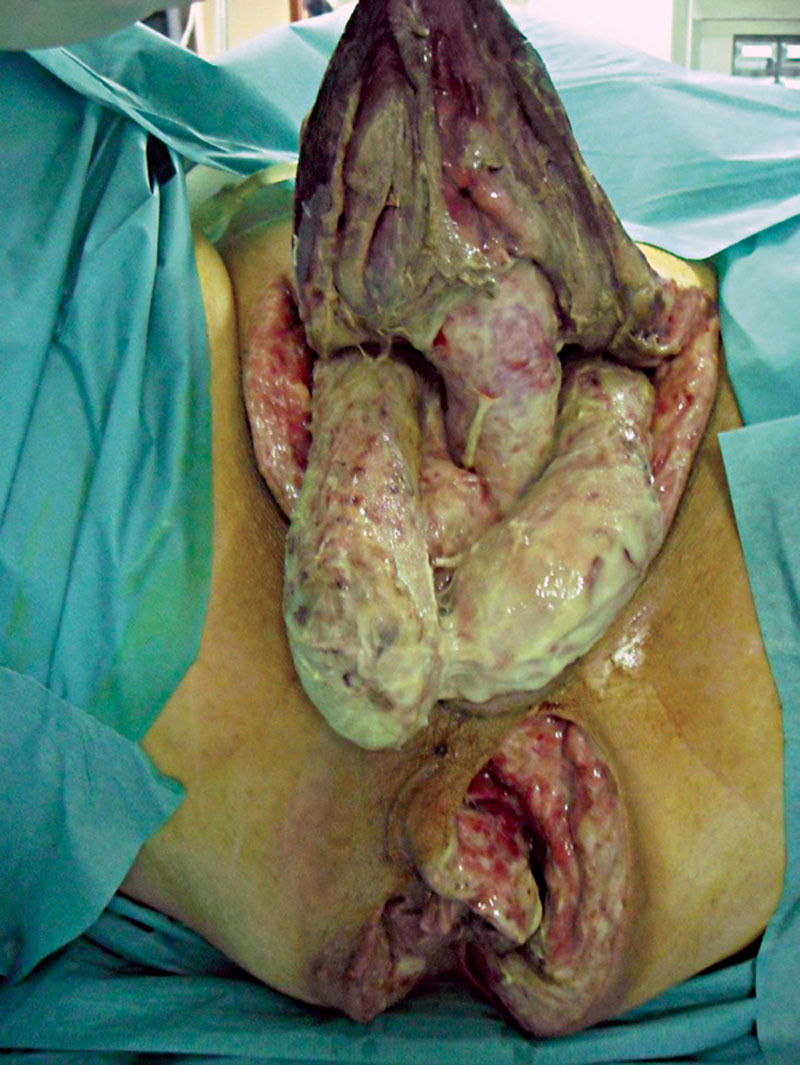

We started treatment with aggressive fluid resuscitation and correction of hemodynamic parameters while adding an empirical combination of antibiotics. Owing to the persistently poor health condition of the patient, he was moved to emergency surgery room. Upon examination (Fig. 1), it was found that the scrotum was swollen, empyematous, and hyperemic with necrotic areas and was crackling at palpation. The rectal stump was exposed. The penile rod was edematous, and the scrotum was totally necrosed.

Fig. 1.

Local status before debridement—exposition of the scrotum and testis.

We performed a large incision of the scrotum and didymus denudation. Second, we performed debridement and necrosectomy of the perianal region and also accurate washing of the region with physiological solution and povidone-iodine solution. Finally, after hemostasis revision, we bungholed the region with 8 gauzes. The day after, general condition of the patient improved.

We used foam for advanced dressing on testicles; another type of foam was applied on the anal site; polyurethane foam was applied on perianal wounds. The wounds were carefully monitored in the days following surgery (6 revisions of wounds), and dressing was done once daily. Adjuvant vacuum therapy was applied in the following days.

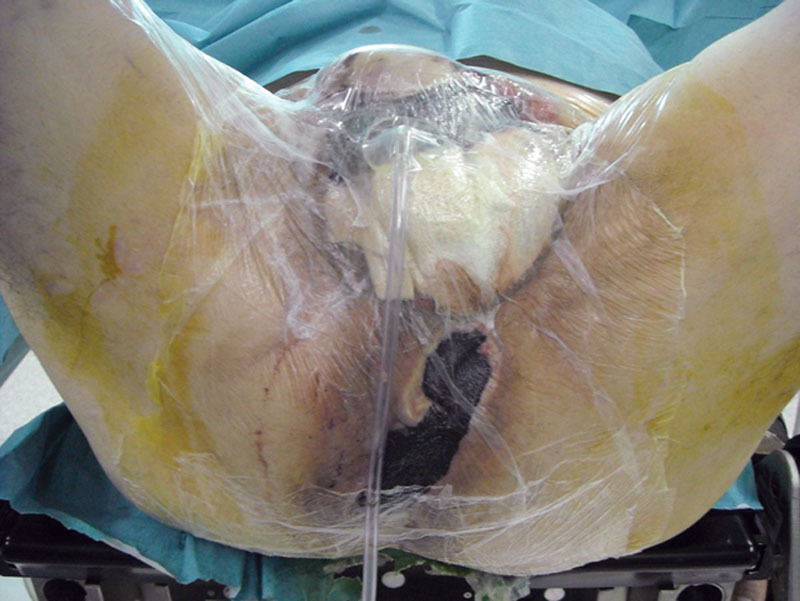

Patient was discharged 42 days after first intervention. Outcomes of the intervention were important: loss of penile and scrotal tissue and bilateral exposure of testicles (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Local status after debridement.

The plastic surgeon presented a possibility of reconstruction of the scrotum with rotation flaps and skin graft. However, the patient refused to undergo reconstruction because of the necessity of many significant interventions. Hence, we proposed a treatment with biological prosthesis. The patient accepted, and we obtained informed consent from him.

One month later, we performed reconstruction of the lost tissue by use of derma porcine prosthesis. After local anesthesia, we prepared residual edges and we debrided adherences. We applied derma porcine mesh to cover the testicles and the penis, and we performed sutures with Vicryl 3/0 (Johnson & Johnson International European Logistics Centre, Diegem, Belgium). We covered biological mesh with patient’s dermis withdrawn by dermatome. On uncovered areas, we applied little patches of foam and vacuum therapy. The penis was reconstructed with circular edges of the biological mesh. We applied vacuum therapy on the biological mesh and on wound defects (Fig. 3). One month later, the patient was healed. Two months later, we performed ultrasound echography of “neoscrotum” that demonstrated whole and healed tissue. We observed no complications at 4-month follow-up.

Fig. 3.

Application of biological prosthesis and vacuum therapy.

Actually, clinical condition of the patient is good, and we did not observe any complications caused by this intervention (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Final result.

Footnotes

Disclosure: The authors have no financial interest to declare in relation to the content of this article. The Article Processing Charge was paid for by the Department of Surgery, University of L’Aquila, L’Aquila, Italy.

REFERENCES

- 1.Levenson RB, Singh AK, Novelline RA. Fournier gangrene: role of imaging. Radiographics. 2008;28:519–528. doi: 10.1148/rg.282075048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thomsen TW, Legome E. Fournier gangrene. Available at: http://www.emedicine.com/emerg/topic929.htm. Accessed April 20, 2006.

- 3.Yalamarthi S, Dayal S. Fournier’s gangrene. Available at: http://www.edu.rcsed.as.uk/lectures/lt33.htm. Accessed April 20, 2006.

- 4.Grayson DE, Abbott RM, Levy AD, et al. Emphysematous infections of the abdomen and pelvis: a pictorial review. Radiographics. 2002;22:543–561. doi: 10.1148/radiographics.22.3.g02ma06543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yanar H, Taviloglu K, Ertekin C, et al. Fournier’s gangrene: risk factors and strategies for management. World J Surg. 2006;30:1750–1754. doi: 10.1007/s00268-005-0777-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Roje Z, Roje Z, Eterović D, et al. Influence of adjuvant hyperbaric oxygen therapy on short-term complications during surgical reconstruction of upper and lower extremity war injuries: retrospective cohort study. Croat Med J. 2008;49:224–232. doi: 10.3325/cmj.2008.2.224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mortensen CR. Hyperbaric oxygen therapy. Curr Anest & Crit Care. 2008;19:333–337. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Champion S. A case of Fournier’s gangrene. Urol Nurs. 2007;27:296–299. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Roje Z, Roje Z, Matić D, et al. Necrotizing fasciitis: literature review of contemporary strategies for diagnosing and management with three case reports: torso, abdominal wall, upper and lower limbs. World J Emerg Surg. 2011;6:46. doi: 10.1186/1749-7922-6-46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brandt MM, Corpron CA, Wahl WL. Necrotizing soft tissue infections: a surgical disease. Am Surg. 2000;66:967–970. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]