Abstract

Synaptotagmin 1 (Syt1) is a synaptic vesicle protein that serves as a calcium sensor of neuronal secretion. It is established that calcium binding to Syt1 triggers vesicle fusion and release of neuronal transmitters, however, the dynamics of this process is not fully understood. To investigate how Ca2+ binding affects Syt1 conformational dynamics, we performed prolonged molecular dynamics (MD) simulations of Ca2+-unbound and Ca2+-bound forms of Syt1. MD simulations were performed at a microsecond scale and combined with Monte Carlo sampling. We found that in the absence of Ca2+ Syt1 structure in the solution is represented by an ensemble of conformational states with tightly coupled domains. To investigate the effect of Ca2+ binding, we used two different strategies to generate a molecular model of a Ca2+-bound form of Syt1. First, we employed subsequent replacements of monovalent cations transiently captured within Syt1 Ca2+-binding pockets by Ca2+ ions. Second, we performed MD simulations of Syt1 at elevated Ca2+ levels. All the simulations produced Syt1 structures bound to four Ca2+ ions, two ions chelated at the binding pocket of each domain. MD simulations of the Ca2+-bound form of Syt1 revealed that Syt1 conformational flexibility drastically increased upon Ca2+ binding. In the presence of Ca2+, the separation between domains increased, and interdomain rotations became more frequent. These findings suggest that Ca2+ binding to Syt1 may induce major changes in the Syt1 conformational state, which in turn may initiate the fusion process.

Introduction

Synaptic vesicle fusion is triggered by inflow of Ca2+ ions into nerve terminals. Synaptotagmin 1 (Syt1) serves as a calcium sensor that triggers rapid synchronous transmitter release in response to an action potential (1–5). Synaptic vesicles undergo a number of preparatory steps for exocytosis, including docking to the plasma membrane mediated by the specialized protein complex termed SNARE (reviewed in (6,7)). Syt1 is thought to interact with the SNARE complex, penetrate into the membrane bilayer, and trigger pore opening (reviewed in (8)). In addition, Syt1 has been implicated in bridging neuronal and vesicle membrane bilayers before the SNARE assembly ((9–11), but see (12)). Although Syt1 structure, dynamics, and Ca2+-binding properties have been extensively studied, it is not yet fully understood how specifically Syt1 triggers fusion.

Syt1 comprises two Ca2+-binding domains, C2A and C2B, which are attached to the synaptic vesicle by a transmembrane helix (13). Each domain has two loops forming a Ca2+-binding pocket where Ca2+ ions are chelated by several aspartic acids (14,15). Ca2+ binding to the C2B domain is critical for synchronous transmitter release (16–18), whereas Ca2+ binding to the C2A domain may play a regulatory role in the coordination of synchronous and asynchronous release components (19–21).

Although it is clear that Syt1 physiological function critically depends on Ca2+ binding and the configuration of C2 domains, these aspects are not yet fully understood. Thus, it was shown that the isolated C2A domain binds three Ca2+ ions (14), whereas the isolated C2B domain binds two Ca2+ ions (15). However, a titration calorimetry study (22) suggested that the C2AB fragment of Syt1 has only four Ca2+-binding sites. Furthermore, a crystallography study of the C2AB fragment of Syt1 (23) revealed a perpendicular orientation and tight coupling of C2 domains where Ca2+-binding loops of C2A domain interacted with C2B domain. The latter findings suggest a possibility that Ca2+ binding can cooperate between C2 domains and that Ca2+-binding properties of isolated domains may not fully account for the kinetics and stoichiometry of Ca2+ binding of Syt1 in vivo.

It is still a matter of debate whether Syt1 function depends on the cooperation of C2 domains and whether the domains are coupled. The crystallography study (23) showed that C2 domains are tightly packaged and interact, however, optical studies suggest that in the solution Syt1 exists as an ensemble of conformers (24) and that C2 domains may be flexibly linked and may not interact (25,26). On the other hand, functional studies showed that C2A domain influences the membrane penetration of C2B domain (27,28) and that mutating the linker connecting C2 domains markedly affects the Syt1 function (29). Thus, a synergistic action of C2 domains is likely (30).

Rapid synchronous exocytosis occurs at a submillisecond scale, with a delay between Ca2+ entry and the onset of postsynaptic response being on the order of 150–200 μs (31,32), and a major part of this time is probably occupied by the fusion pore dilation and the diffusion of the transmitter across the synaptic cleft (33). Thus, it is likely that the protein fusion machinery acts at a scale of several microseconds or possibly tens of microseconds. Although an experimental detection of protein conformational transitions at a microsecond timescale may not be currently feasible, computational methods, such as molecular dynamics (MD), could provide valuable insights. In this study, we performed the first, to our knowledge, all-atom MD simulations of the Syt1 C2AB fragment at a microsecond timescale with the goal to investigate the ensemble of its conformational states in the presence and in the absence of Ca2+.

Materials and Methods

Monte Carlo minimization

The Monte-Carlo minimization (MCM) approach (34) with the ZMM/MVM software package (http://www.zmmsoft.com, (35)) was employed for the initial optimization of Syt1 structure and for the generation of additional conformational states. Unless stated otherwise, MCM computations were performed in the space of all the torsion and bond angles of a molecule without restrains. Distance-dependent electrostatic potential was used to implicitly simulate water environment.

System setup

2R83 structure (23) was used for an initial approximation of Syt1 conformation. This structure was initially optimized employing MCM. The optimized structure was placed in a water box (100 × 100 × 100 A) constructed using Visual Molecular Dynamics Software (VMD, Theoretical and Computational Biophysics Group, NIH Center for Macromolecular Modeling and Bioinformatics, at the Beckman Institute, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, IL). Potassium and chloride ions were added to neutralize the system and to yield 150 mM concentration of KCl.

A Syt1 conformation with a stretched linker was obtained by applying harmonic distance constraints and performing MCM optimization with ZMM software. The constraints were applied to the residues R199 of the C2A domain and D392 of the C2B domain. All the internal variables of the Syt1 molecule, including bond lengths, bond angles, and torsion angles were kept rigid, with the exception of the backbone torsion angles of the linker residues 266–273. This approach allowed us to derive the Syt1 conformation where domain structure remained identical to that obtained by crystallography but C2 domains were separated and did not interact.

An additional set of conformations with modified domain arrangement was obtained by Monte Carlo (MC) sampling of all the linker backbone torsions (residues 266–273). The structures with overlapping atoms were rejected, and the remaining structures were optimized by MCM. All the obtained structures were placed in water boxes with ions added, as described previously.

MD

MD production runs were performed at Anton supercomputer (36) with Desmond software through the MMBioS (University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA; National Center for Multiscale Modeling of Biological Systems; Pittsburg Supercomputing Center, Pittsburgh, PA; and D. E. Shaw Research Institute, New York, NY). The initial equilibration (100–200 ns) was performed employing NAMD scalable molecular dynamics (37) (Theoretical and Computational Biophysics Group, NIH Center for Macromolecular Modeling and Bioinformatics, at the Beckman Institute, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign) at XSEDE (Extreme Science and Engineering Discovery Environment) Stampede cluster (TACC). Both NAMD and Desmond simulations were performed employing CHARMM22 force field (38) with periodic boundary conditions and Ewald electrostatics in isothermal-isobaric ensemble at 300 K with a time step of 2 fs.

Analysis and visualization

The trajectory analysis was performed employing VMD and Vega ZZ (Drug Design Laboratory, University of Milan, Milan, Italy) software; PyMOL software was used for visualization, molecular graphics, and illustrations. Quantitative analysis was performed using MATLAB (The MathWorks, Natick, MA). In production runs, the time-step between trajectory points was 240 ps.

Syt1 conformations were classified by interdomain rotation torsion and bending plain angles (Fig. 1 A). The torsion angle was defined by Cα atoms of the residues G305-E350-N154-M173. The value of 0° or 360° for the interdomain rotation torsion corresponds to Ca2+-binding pockets (residues G305 and M173) facing the same surface, whereas the angle of 180° corresponded to Ca2+-binding pockets facing opposing surfaces. The bending angle was defined by Cα atoms of the residues M173-L273-G305. This corresponded to the plain angle connecting Ca2+-binding pockets (M173 and G305) with the linker (L273).

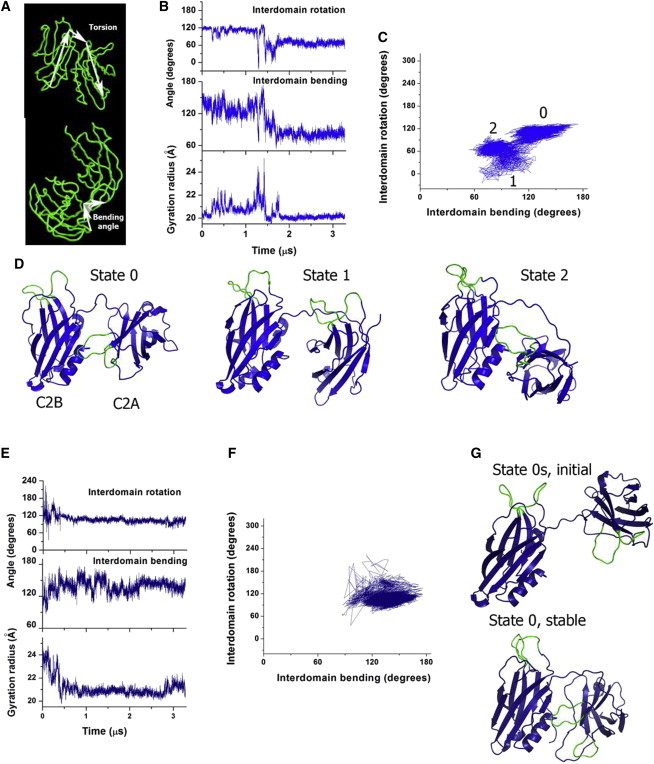

Figure 1.

Syt1 conformational state obtained by crystallography is relatively stable in a water/ion environment, however interdomain rearrangements can occur at a microsecond scale. (A) Interdomain rotation torsion (top) and bending plain (bottom) angles defining configuration of C2 domains. (B) MD trajectory started from the conformation obtained by crystallography. (C) The same trajectory presented in the space defined by bending and rotation. The initial state 0, a transitional state 1, and a final stable state 2 are labeled. (D) Structures corresponding to the states 0, 1, 2 are shown. Ca2+-binding loops are colored green. All the structures are shown with a similar orientation of the C2B domain. (E) MD trajectory started from the stretched state 0s. (F) The same trajectory presented in the space of bending and rotation. (G) The initial state 0s and the final stable state with tightly coupled domains (bottom, state 0). To see this figure in color, go online.

Conformational energy was computed as a sum of the energy of the protein and the energy of nonbonded interactions of the protein with water molecules and ions.

To describe the domain separation, we used the value of the gyration radius, defined as the root mean-square distance of all the backbone atoms from their center of mass. Interdomain van der Waals energy was used as an additional measure of domain separation and coupling, and it was computed between the residues 140–265 (C2A domain) and the residues 273–418 (C2B domain).

Results

In the absence of Ca2+, Syt1 exists as an ensemble of conformations with tightly interacting domains

First, we investigated the stability of Syt1 structure obtained by crystallography (23). We performed a prolonged (3.3 μs) MD simulation of the Syt1 molecule in a water/ion environment starting from the optimized 2R83 x-ray structure (trajectory R0, Table 1). To analyze interdomain configuration along the trajectory, we calculated the torsion angle corresponding to interdomain rotation, the plane angle corresponding to relative bending of the domains against the middle of the linker (Fig. 1 A), and the gyration radius, reflecting the separation of the domains.

Table 1.

Summary of MD simulations

| MD Trajectory | Simulation Time (μs) | Initial State | Final State | Figure |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ca2+unbound Syt1 | ||||

| R0 | 3.3 | optimized x-ray, State 0 | CS4 | 1B–D |

| R0s | 3.3 | stretched x-ray, state 0s | CS1 | 1E–G |

| R1 | 3.3 | MC, state 1 | CS2 | 2B |

| R2 | 3.3 | MC, state 2 | CS1 | 2B |

| R3 | 3.3 | MC, state 3 | CS3 | 2B |

| Ca2+-bound Syt1 | ||||

| R4Ca | 5.5 | state 0 bound to 4 Ca2+ | 4, 5, S7 | |

| RHCa1 | 3.3 | state 0 at elevated Ca2+ | S5, A–C | |

| RHCa2 | 3.3 | state 1 at elevated Ca2+ | S5, D–F | |

| R5Ca | 0.25 | state 0 bound to 5 Ca2+ | S6 | |

We found that Syt1 interdomain configuration remained stable for ∼1.1 μs (Fig. 1, B–D, state 0), although minor fluctuations of the interdomain torsion and bending angles, as well as of the gyration radius were observed within this period. Subsequently, a conformational transition occurred (Fig. 1, B–D, state 1), the domains separated (note a transient increase in the gyration radius around 1.2 μs, Fig. 1 B), and the structure transitioned into a different state (Fig. 1, B–D, state 2). State 2 had tightly interacting domains (Fig. 1 C) and C2A domain was rotated against C2B domain by ∼60°. This conformation remained stable for the remaining 1.5 μs of the simulation, without significant fluctuations in either gyration radius or interdomain torsion and bending angles (Fig. 1 B, the interval between 1.8 and 3.3 μs).

This result suggests that Syt1 conformation obtained by crystallography is relatively stable in the solution, but at a microsecond timescale C2 domains can undergo rearrangements. To further test this idea and to ensure that the structure is not trapped in a local energy minimum, we performed MD simulations of Syt1 starting from a conformation with a stretched linker (run R0s, Table 1, Fig. 1, E–G). After an initial period of instability (∼0.5 μs, Fig. 1 E), where considerable interdomain rotation and bending was observed, the domains came close together (note a decrease in the gyration radius, Fig. 1 E), and the structure stabilized (Fig. 1 G, bottom, final stable state). No major interdomain rotation or bending occurred within this run, with the exception of relatively brief and transient change in the bending and rotation angles within the initial 0.5 μs of the trajectory (Fig. 1 E). This result provides further evidence that the conformation with tightly interacting and perpendicularly oriented domains (state 0, Fig. 1, D and G) is fairly stable in the solution. However, the conformational transition observed during the first run (Fig. 1, B–D), suggests that Syt1 may adopt different conformations in a physiological environment, and that an ensemble of Syt1 conformational states may coexist in the solution.

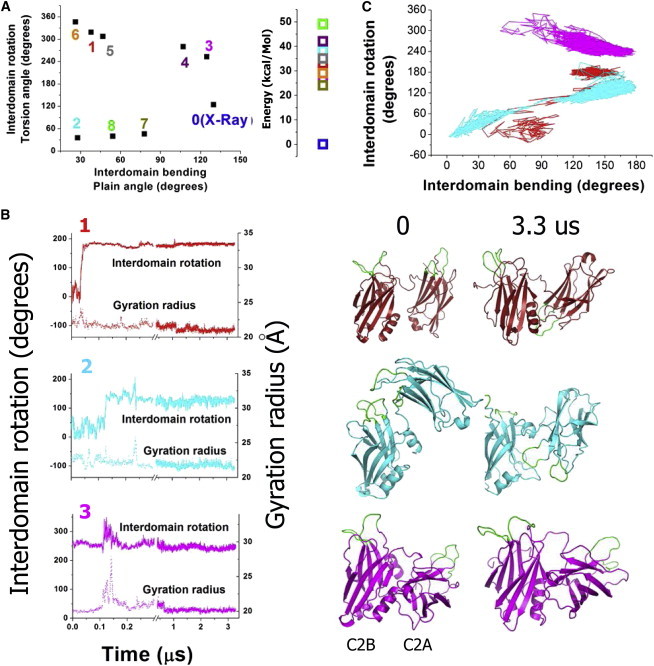

To test this possibility, we generated a new, to our knowledge, set of Syt1 conformations employing MC sampling of the linker backbone torsions. States 0 and 0s were used to generate this new, to our knowledge. set of Syt initial states. For each of the states 0 and 0s, backbone torsion angles of the linker (residues 266–273) were sampled randomly to generate 100 different Syt1 topologies, and thus, a total of 200 Syt1 topologies were generated. Subsequently, conformations with overlapping atoms were rejected. This procedure produced 16 different Syt1 conformations (Fig. S1 in the Supporting Material), which were used as initial states for MCM optimization. After the optimization, nine conformations (Fig. S2; Fig. 2 A) fell within a relatively low energy range (50 kcal/mol, Fig. 2 A), although others had significantly higher energies (over 100 kcal/mol). The optimized low energy states had tightly interacting C2 domains (Fig. S2), with only one exception (state 7, Fig. S2). Three of these conformations (1–3, Fig. S2) were used as initial states for subsequent MD runs (Fig. 2 B; Table 1, trajectories R1–R3). These states were chosen with the goal to broadly sample the permissive conformational space (Fig. 2 A) of Syt1.

Figure 2.

Conformational analysis of Ca2+-unbound form of Syt1 (A) Conformational states of Syt1 obtained by MC sampling, including their topologies (left) and energies (right). Energies are plotted in relation to the state obtained by crystallography (state 0, E = 0 kcal/mol). (B) MD trajectories started from MC states 1, 2, 3 (colors of the trajectories match initial states shown in A). Initial and final conformations are shown on the right (0 and 3.3 μs). (C) The same trajectories as in (B) presented in the conformational space defined by interdomain rotation and bending. To see this figure in color, go online.

The states 1 and 2 underwent major conformational transitions in the beginning of MD trajectories R1 and R2, respectively (within the initial 0.3 μs of the simulation, see Fig. 3 C, red and cyan; note an increase in the gyration radius and a change in the interdomain torsion angle, indicating a separation between the domains and their rotation). In the state 3 (see Fig. 3 C, magenta), the separation between the domains in the beginning of the trajectory R3 occurred as well (note a transient increase in the gyration radius and fluctuations in the torsion angle between 0.1 and 0.2 μs), however, the domains did not rotate, the gyration radius decreased, and the conformation stabilized. The three runs R1–R3 (Table 1) are summarized in Fig. 3 D, showing major conformational transitions during the runs R1 and R2 (red and cyan).

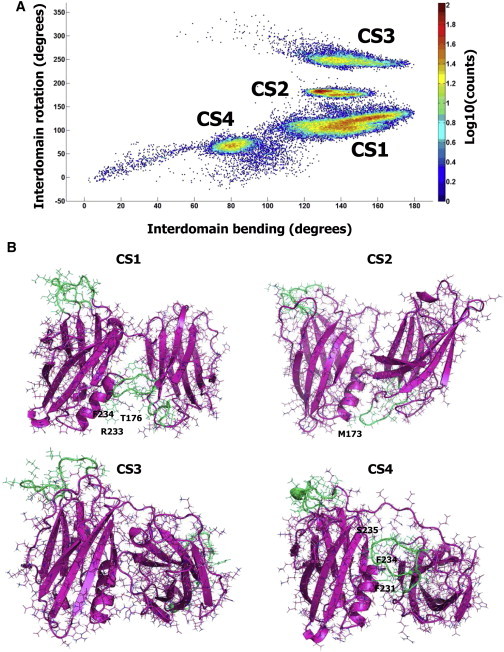

Figure 3.

Highly populated conformational states of Ca2+-unbound form of Syt1. (A) All the MD trajectories pooled together and plotted in the space of interdomain bending and rotation reveal four highly populated conformational states, CS1–CS4. Each point on the graph represents the number of observations color coded according to the logarithmic scale shown on the scale bar at all the trajectories pooled together. (B) States C1–C4 are shown with similar orientations of C2B domains. The residues of C2A Ca2+-binding loops interacting with C2B domain are labeled. To see this figure in color, go online.

Thus, we performed a total of 16.5 μs MD simulations starting from five different initial states (Figs. 1 and 2; Table 1). This allowed us to map the population density (Fig. 3 A) and to determine the ensemble of highly populated states (Fig. 3 B) of Syt1. All these conformational states (CS1–CS4, Fig. 3 B) had tightly coupled domains, and interdomain interactions in the states CS1, CS2, and CS4 were stabilized by contacts between Ca2+-binding loops of the C2A domain and C2B domain.

According to its C2 domain configuration, the conformation observed by crystallography belongs to the CS1 cluster. However, significant fluctuations in the bending angle and interdomain torsion were observed within this state (Fig. S3 A; also note the broad area occupied by the state CS1 in Fig. 3 A), and several CS1 substates could be distinguished (Fig. S3 B). In all the substates, interdomain interactions occurred between the C2A residues R233-F234 and either β8 (I401-T406, Fig. S2 B.1) or α2 (G384-A395, Fig. S3 B.2) of the C2B domain. Furthermore, partial melting of the C2B α2 helix was observed along the trajectory, and the melted part formed tight links with the residue F234 (Fig. S3 B.3). In several points of the trajectory, the partially unstructured α2 helix came into contact with both Ca2+-binding loops of the C2A domain (Fig. S3 B.4). In addition, all the C1 substates were stabilized by an interaction of the polylysine motif K189–K192 of C2A domain and the poly-E motif E410–E412 of C2B domain (Fig. S3, B–E).

Highly populated states CS2, CS3, and CS4 (Fig. 3, A and B), corresponded to the final states of the trajectories presented in Figs. 1 B and 2 B (runs R1, R3, and R0, respectively, Table 1). In the states CS2 and CS4, interdomain interactions were stabilized by the contacts between Ca2+-binding loops of C2A domain and α2 helix of C2B domain, similar to the state CS1. In contrast, the state CS3 was roughly symmetrical to the state CS1, with C2A Ca2+-binding loops being separated from the C2B domain (Fig. 3 B, C3). Notably, neither of the trajectories that started from unstable conformations (Figs. 1, E–G, and 2 B, runs 1–2) converged into state CS3. In contrast, all such trajectories converged into states CS1 or CS2, characterized by coupling of C2A Ca2+-binding loops with the C2B domain. Thus, it is possible that the state CS3 represents a local energy minimum where the structure is trapped.

To address the question of energy difference between the states and to explore the energy barriers, we computed the average energies within each cluster, as well the energy profile along the trajectory R0 (Table 1), which produced a conformational transition between the states CS1 and CS4 (Fig. S4). The energy was computed as the energy of a protein plus the energy of nonbonded protein/water and protein/ions interactions. Interestingly, we found that the conformational transition between the states CS1 and CS4 was not associated with any significant energy barrier (Fig. S4 A). The state CS1 had the lowest energy (Fig. S4 B), as could be expected based on its high occupancy, however the differences between the energies of the four states were within the fluctuations along trajectories (Fig. S4, A and B).

Notably, the four clusters describing the states CS1–CS4 (Fig. 3) are not entirely separated but show overlap. The clusters CS1, CS2, and CS4 overlap significantly (note multiple points between the clusters, Fig. 3 A), whereas cluster CS3 is somewhat isolated. However, intermediate trajectory points can be found even between the clusters CS3 and CS2 (Fig. 3 A, note blue dots between these two areas). Furthermore, the trajectories of all the MD runs taken together (Fig. 3 A, blue dots) cover the entire sterically permissive space of Syt1 configurations with tightly packed domains. This space represents a triangular pattern, where the highest values of the bending angle are only permissive at the values of the interdomain torsion angle being close to 180°, whereas lower bending angles are permissive at the values of the interdomain torsion angle approaching either 0° or 360°. In other words, the bending angle must increase when C2A and C2B Ca2+-binding pockets face the opposite sides, and the bending angle must decrease when Ca2+-binding pockets face the same surface. Notably, MC sampling produced a similar triangular pattern for the low energy state (Fig. 2 A). This restriction on the conformational space is imposed by tight interactions between domains.

Interestingly, the states with Ca2+-binding loops facing the same surface (interdomain torsion close to 0° or 360°) proved to be unstable. Such states served as starting points for two trajectories (runs R1 and R1, Table 1; Fig. 2 B) and were occasionally observed along all the other trajectories presented in Figs. 1 and 2. However, all such states converged into conformations CS1–CS4. Furthermore, the states with separated domains proved to be unstable as well (note only brief and transient jumps in the values of the gyration radius in Figs. 1 and 2). Instead, all the highly populated states had tightly interacting domains (Fig. 3 B).

Thus, prolonged MD simulations combined with MC sampling demonstrated that in the absence of Ca2+, Syt1 exists as an ensemble of conformational states with tightly coupled domains, and these states are stable at a microsecond scale. These conformations are largely stabilized by the interactions between C2A Ca2+-binding loops and C2B domain, and in particular its α2 helix. The most populated state (CS1) possesses some conformational flexibility and allows minor rearrangements within and between domains, thus comprising an ensemble of substates. One of these substates corresponds to the conformation obtained by crystallography (23).

Ca2+ binding destabilizes the interaction between the C2A and C2B domains and facilitates conformational transitions

Because Ca2+-binding loops of C2A domain play a prominent role in interdomain interactions, one could expect that Ca2+ binding may affect Syt1 conformational dynamics. To test whether this is the case, we performed MD simulations of Syt1 in a Ca2+-bound form.

First, we created a model of C2AB Syt1 in a Ca2+-bound form. To do this, we performed sequential substitutions of K+ ions that were present inside Ca2+-binding pockets of Syt1 by Ca2+. Initially, we examined the motions of K+ ions along MD trajectories of Syt1 in a Ca2+-unbound form and found that K+ ions were frequently moving in and out of both Ca2+-binding pockets and occasionally remained inside the pockets for nanoseconds. Two K+ ions were occasionally present at the same time inside one of the pockets; however, we never detected more than two K+ simultaneously present inside either of the pockets.

Next, we selected a trajectory point with two K+ ions located inside the C2B Ca2+-binding pocket and replaced these two K+ ions by Ca2+ (the number of K+ and Cl− in the cell was modified to keep the system electrically neutral). MD simulations (100 ns) of this new, to our knowledge, system were then performed and at the next step a trajectory point was selected with two K+ ions trapped inside the C2A Ca2+-binding pocket. These two ions were in turn replaced by Ca2+. The obtained structure was stripped of water molecules and K+ ions, optimized by MCM, and placed in a water box with K+ and Cl− added to keep the system electrically neutral and yield 150 mM KCl. The system was equilibrated for 200 ns, and a 5.3 μs production run was performed.

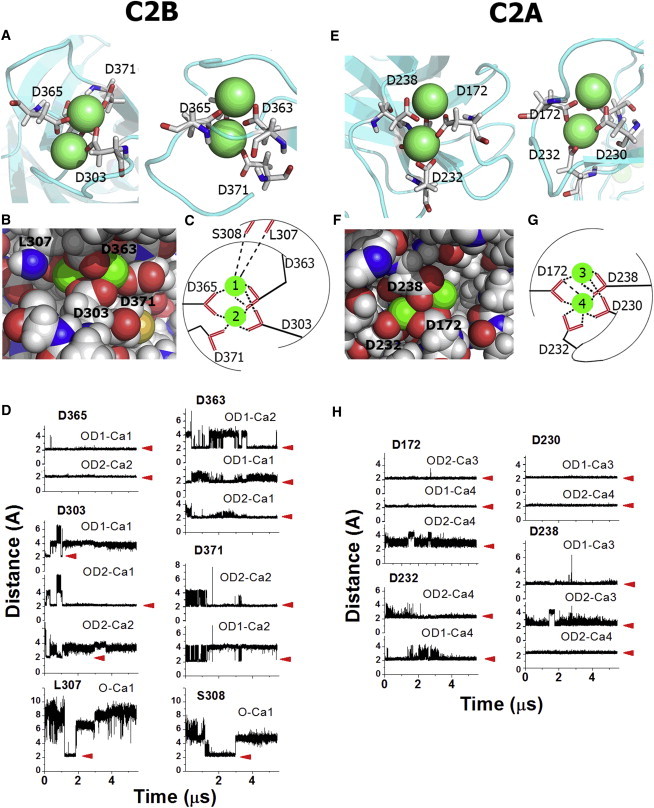

We found that the positions of Ca2+ ions within the pockets remained stable during the entire simulation (Fig. 4). Two Ca2+ ions within the C2B pocket formed coordination bonds with aspartates D363, D365, D371, and D303 (Fig. 4, A–D). The residue D365 formed two stable bonds with two Ca2+ ions, whereas each of the other aspartates formed one stable coordination bond, with additional one or two transient bonds at stretches of the trajectory (Fig. 4 D). Two additional residues, L307 and S308, formed transient bonds via their backbone carbonyl oxygens with one of the Ca2+ ions (Fig. 4, B–D). The observed coordination is very similar to that reported for the isolated C2B domain (4) with one exception: the residue D309, which participated in Ca2+ binding of the isolated C2B domain did not come into contact with either of the Ca2+ ions at either point of the trajectory in this model.

Figure 4.

The model of Ca2+-bound form of Syt1. (A) Two views (from opposite sides) of the C2B Ca2+-binding pocket. Residues forming coordination bonds are labeled. (B) Space filled model of Ca2+ ions chelated at the C2B Ca2+-binding pocket. (C) Schematic representation of Ca2+ coordination bonds at C2B domain. (D) Coordination bonds at C2B domain along the trajectory. The distances between Ca2+ ions and oxygen atoms are plotted, red arrows mark formed coordination bonds. (E–H) Ca2+ binding at the C2A domain (similar to A–D for C2B domain) is shown. To see this figure in color, go online.

Two Ca2+ ions within the C2A binding pocket formed coordination bonds with aspartates D230, D232, D238, and D172 (Fig. 4, E–H), with each of the residues D172 and D238 forming three fairly stable bonds, whereas D232 and D230 formed two bonds each (Fig. 4, G and H). At stretches of the trajectory, remaining Ca2+ coordination bonds were occupied by water molecules (removed from Fig. 4 for clarity). Ca2+ ions were chelated tightly within the pocket, so that it did not appear feasible to fit an extra ion (Fig. 4 F). Although Ca2+-binding stoichiometry differed from that reported for the isolated C2A domain (14), the same aspartates (D172, D230, D232, D238) participated in chelating Ca2+. The only exception was the residue D178, which did not participate in Ca2+ binding in our system.

Thus, our simulations suggest that C2AB Syt1 chelates four Ca2+ ions, two at each of the Ca2+-binding pockets. This result agrees with the titration calorimentry study for C2AB Syt1 (22) and with Ca2+-binding stoichiometry obtained for the isolated C2B domain (15), but it does not reproduce Ca2+ stoichiometry for the isolated C2A domain (14). To test whether our results could be influenced by the strategy we used to obtain the Ca2+-bound Syt1 form, we tried a different modeling approach.

To further explore the mechanism of Ca2+ binding to Syt1, we performed MD simulations of Syt1 at elevated Ca2+ levels. To do this, we took the CS1 state of Ca2+-unbound Syt1 (Fig. 3) in a water/KCl environment and replaced KCl by CaCl2, while keeping the system electrically neutral. This manipulation yielded ∼100 mM Ca2+. Even though such Ca2+ levels exceed the physiological concentration by orders of magnitude, our goal was to push the limits and to test whether three Ca2+ ions could enter the C2A-binding pocket at artificially elevated Ca2+ levels. We performed 3.4 μs MD simulation for this system, and found that only two Ca2+ ions were present inside each of the Ca2+-binding pockets in the end of the trajectory. Within the initial 50 ns of the simulation, two Ca2+ ions entered the C2B-binding pocket and one Ca2+ ion entered the C2A-binding pocket, whereas the fourth Ca2+ ion entered the C2A-binding pocket after an additional 200 ns of the simulation. Subsequent 3.2 μs of MD simulations did not alter Ca2+ stoichiometry of Syt1. All four Ca2+ ions remained inside the binding pockets until the end of the trajectory and formed coordination bonds with residues D303, D309, D363, D365, and D371 of the C2B domain and residues D178, D230, D232, and D238 of the C2A domain (Fig. S3, A–C). The coordination bonds formed by Ca2+ ions were similar to those obtained during the previous run (Fig. 4), with three following exceptions. First, residue D309 of C2B domain formed a transient coordination bond with one of the Ca2+ ions during the latter MD run (Fig. S5 B). Second, residue D178 of C2A domain formed a coordination bond (Fig. S5 C). Finally, residue D172 did not interact with any of the four chelated Ca2+ ions during the latter run (Fig. S3 C).

We next questioned whether Ca2+ binding may depend on the Syt1 conformational state. For example, if C2 domains are separated, Ca2+ binding could more closely reproduce the properties of isolated domains. To test this possibility, we performed MD simulations at elevated Ca2+ levels, repeating the procedure described previously but using a different Syt1 conformation as a starting point. We selected a transient Syt1 state (run R1 shown in Fig. 2 B at 200 ns) where C2A Ca2+-binding loops did not interact with the C2B domain (Fig. S5 D). We performed 3.3 μs of MD simulations for this system, and as previously, only four Ca2+ ions were chelated within Syt1 binding pockets, two ions at each domain (Fig. S5, D–F). Residues D363, D365, D371, D303, and D309 chelated two Ca2+ inside the C2B pocket and residues D172, D178, D230, and D238 chelated two Ca2+ ions inside the C2A pocket.

Finally, we attempted to manually insert the third Ca2+ ion into the C2A Ca2+-binding pocket (Fig. S6). First, we examined the distance between C2A Ca2+-binding loops along the R4Ca trajectory (Fig. S6 A, left) and found that the loops open up at several trajectory points, thus enabling the insertion of the third Ca2+ ion. We selected the trajectory point with a C2A binding pocket being open (Fig. S6 A, arrow) and inserted the third Ca2+ ion (Fig. S6 B). The system was neutralized, and a water/ion environment was reequilibrated. Subsequent 250 ns simulation (Table 1, run R5Ca) demonstrated that chelation of three ions within the C2A domain involves the residue that does not belong to C2A Ca2+-binding loops (Fig. S6 C), namely glutamate E140. Such stoichiometry of Ca2+ chelation is likely to represent a simulation artifact, because E140 is the N-terminus residue of the C2A-C2B fragment. In full length Syt1, glutamate E140 belongs to the linker between the Syt1 transmembrane domain and the C2A domain. In the vesicle attached full length Syt1 in vivo this linker is unlikely to provide sufficient flexibility for E140 interaction with the C2A Ca2+-binding pocket. Furthermore, there is no evidence in the literature that the residue E140 participates in Ca2+ chelation. Thus, these simulations indicate that it is unlikely that three Ca2+ ions become chelated within the C2A Ca2+-binding pocket in full-length Syt1 in vivo.

Thus, several MD runs performed at different conditions (Table 1, Ca2+-bound Syt1) suggest that Syt1 robustly binds four Ca2+ ions, two at each domain. In agreement with earlier studies (14,15), these simulations show that Ca2+ ions are chelated by aspartates D303, D309, D363, D365, and D371 of C2B domain and aspartates D172, D178, D230, D232, and d238 of C2B domain. Interestingly, these simulations also indicate that these residues may have different weights in Ca2+ coordination. Thus, loop 2 (residues 363–371) of the C2B domain robustly interacted with both Ca2+ ions, and aspartates D363, D365, and D371 formed stable coordination bonds. Loop 1 of the C2B domain (residues 303–309) appeared more flexible, and stable bonds were formed by D303, although the bonds formed by D309 were transient and were not detected in every run. Two Ca2+ ions chelated within the C2A-binding pocket formed stable coordination bonds with residues D230 and D238 of loop 2. In contrast, D232 and both aspartates of loop 1, D172 and D178, formed more transient bonds, and thus, may have a supportive role in Ca2+ binding.

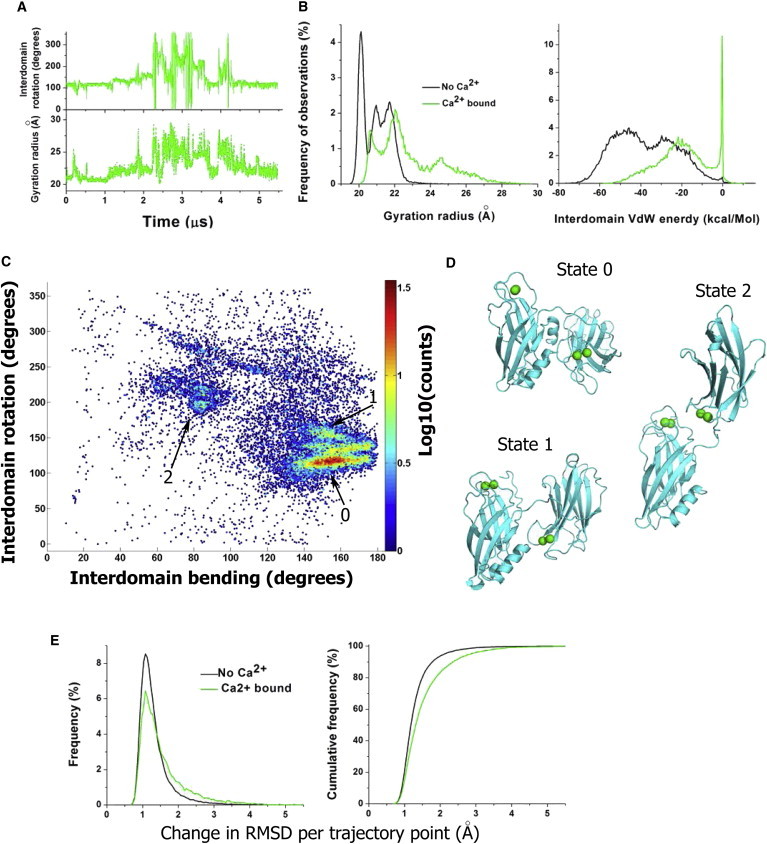

We next investigated how Ca2+ binding affects Syt1 conformational dynamics. To do this, we analyzed the trajectory of Ca2+-bound Syt1 form (R4Ca, Table 1; Fig. 4), including interdomain rotations, gyration radius, and van der Waals energy of interactions between C2 domains. The trajectories obtained at high Ca2+ levels (R1HCa and R2HCa, Table 1; Fig. S5) were not included in the analysis, because we reasoned that artificially elevated Ca2+ may affect domain coupling. The analysis of 5.3 μs MD trajectory of the Ca2+-bound form of Syt1 revealed numerous separations and rotations of C2 domains (Fig. 5 A). The domains separated after ∼1 μs of the simulation, and subsequently multiple conformational transitions occurred (Fig. 5 A; Fig. S7). The coupling between domains was not as tight as in the Ca2+-unbound state of Syt1, as illustrated by the comparison of the gyration radius and van der Waals energy of interdomain interactions of Ca2+-bound and Ca2+-unbound Syt1 forms (Fig. 5 B).

Figure 5.

Conformational states of Ca2+-bound form of Syt1. (A) MD trajectory showing multiple domain rotations (top) and domain separations (bottom, note fluctuations in the gyration radius). (B) The distributions of the gyration radius and van der Waals energy of interdomain interactions are shifted to the right for the Ca2+-bound form of Syt1 (green). (C) MD trajectory shown in the space of interdomain bending and rotation. Each point on the graph shows a color-coded number of observations (per logarithmic scale on the right). Three highly populated states (0–matching the initial states, 1 and 2) are marked. (D) Three highly populated states (0–2). (E) Conformational flexibility is increased in the Ca2+-bound form of Syt1. The graphs show frequency of observations (left) and cumulative frequency (right) for the change in RMSD per trajectory point (240 ps). RMSD was calculated for backbone atoms only. The change in RMSD per trajectory point is significantly higher for the Ca2+-bound form (p < 0.001 per K.S. test). To see this figure in color, go online

In the Ca2+-bound Syt1 form, the distribution of the gyration radius is shifted to the right (Fig. 5 B, green versus black). Notably, this distribution has the highest peak around 20.3 μm for the Ca2+-unbound Syt1 form (Fig. 5 B, black), and this peak is absent for the Ca2+-bound form (Fig. 5 B, green). This peak corresponds to Syt1 conformations with tightly coupled and perpendicularly oriented domains, such as in the states C1, C3, and C4 (Fig. 3). On the other hand, a peak at 24.5 A exists for the Ca2+-bound Syt1 form (Fig. 5 B, green), and this peak is absent for the Ca2+-unbound Syt1 form. This peak corresponds to Syt1 topologies with C2 domains being separated and not interacting (for example, Fig. S4, points at 2, 2.5, and 3.3 μs).

In line with these results, all the Ca2+ free forms of Syt1 have negative van der Waals energy computed for interactions between C2A and C2B domains. Because van der Waals attractive forces decay rapidly as the distance between atoms increases, the negative van der Waals energy indicates tight domain coupling. In contrast, a large population of conformations with separated C2 domains existed within Ca2+-bound forms of Syt1. This is evident from a large peak at the probability density function at zero energy (Fig. 5 B, right panel), which corresponds to an absence of van der Waals interactions between C2 domains.

Clearly, the preference for the stretched linker and separated domains should facilitate conformational transitions for the Ca2+-bound Syt1 form. Indeed, the trajectory of Ca2+-bound Syt1 was characterized by frequent conformational transitions (Fig. 5 A; Fig. S4). Furthermore, a structure with separated domains would not impose any restrictions on domain configuration. Indeed, Syt1 topologies along the trajectory covered the entire conformational space defined by interdomain bending and rotation (Fig. 5 C). However, even though permissive topologies of the Ca2+-bound form of Syt1 occupied the entire conformational space (Fig. 5 C, blue dots), several states had an increased population density (Fig. 5 C, spots colored from cyan to red; Fig. 5 D, states 0–2). The state with the highest population density (state 0, Fig. 5, C and D), had a perpendicular orientation of C2 domains and was similar to state C1 of Ca2+-unbound Syt1 (Fig. 3), although the domains were not as tightly coupled in the Ca2+-bound form. The second state (state 2, Fig. 5, C and D), had more parallel orientation of C2 domains and Ca2+-binding pockets facing opposite surfaces. Finally, in the state 3, Ca2+-binding loops of C2 domains interacted with each other. Interestingly, neither of the highly populated states had Ca2+-binding pockets facing the same surface.

Thus, Ca2+ binding significantly promotes conformational transitions of Syt1. This is illustrated in Fig. 5 E, showing the change in root mean-square deviation (RMSD) per trajectory point for the Ca2+-bound and Ca2+-unbound forms of Syt1. The distribution of the change in RMSD is shifted to the right for the Ca2+-bound form (Fig. 5 E), showing larger conformational transitions per trajectory point. Notably, the variability in RMSD in both Ca2+ free and Ca2+-bound Syt1 forms is largely produced by variations in C2 domain configuration, although only minor rearrangements were detected within C2 domains (Fig. S7). C2A domain did not undergo any significant changes within any of the trajectories, besides minor and transient variations in the arrangements of the loops. Somewhat larger variations within the C2B domain (Fig. S7, red) were produced by displacements of its C-terminus helix and did not involve any other conformational transitions within the domain.

In summary, our results show that Ca2+ binding drastically changes the ensemble of Syt1 conformational states. Ca2+-unbound form of Syt1 represents an ensemble of distinct states with tightly coupled domains and infrequent conformational transitions, occurring at a microsecond scale (Fig. 3). In contrast, Ca2+-bound form of Syt1 represents a dynamic ensemble of conformations with frequently separating and rotating C2 domains (Fig. 5).

Discussion

In this study, we performed the first, to our knowledge, all-atom MD simulations of C2AB Syt1 at a microsecond scale. We found that Ca2+ binding significantly enhances conformational flexibility of Syt1, promotes conformational states with separated domains, and accelerates conformational transitions, allowing C2 domains to rotate more freely. It is likely that such dramatic change in Syt1 conformational dynamics upon Ca2+ binding would affect Syt1 function in vivo.

Ca2+ binding to Syt1 is a major event in neuronal secretion, and thus structure and dynamics of Syt1 has been extensively studied. Spectroscopy studies suggested that the structure of isolated Syt1 domains does not change upon Ca2+ binding (39), although recent studies (40,41) challenged this conclusion. Considerable controversy exists on the issue of configuration of C2 domains, its dependence on Ca2+ binding, and its function in vivo. Thus, a crystallography study (23) revealed tightly interacting domains, whereas optical studies suggested that in the solution C2 domains do not interact and can rotate freely (26). Furthermore, electron paramagnetic resonance studies suggest that Syt1 remains structurally heterogeneous even upon binding to the SNARE complex (42), although fluorescence resonance energy transfer studies (24,43) argue that Syt1 adopts a fixed conformation upon binding to the SNARE complex, with the C2B domain of Syt1 playing a primary role in these interactions.

Our analysis revealed that in the solution Ca2+-unbound form of Syt1 exists as an ensemble of conformers with tightly coupled domains. Notably, even in a water/ion environment Syt1 structure had a preference for domain configuration observed by crystallography. Highly populated conformational states of Syt1 revealed by our analysis had either perpendicularly oriented domains or parallel domains with Ca2+-binding pockets facing opposite surfaces. Interestingly, the configuration with Ca2+-binding pockets facing the same surface proved to be unstable.

To understand how Ca2+ chelation would affect the ensemble of Syt1 conformers, we modeled Ca2+ binding to C2AB Syt1. Our MD simulations suggest that each Ca2+-binding pocket of C2AB Syt1 chelates two Ca2+ ions. In agreement with earlier studies (reviewed in (8)) our MD simulations demonstrated that Ca2+ ions are chelated by five highly conserved aspartic acids at each domain: D172, D178, D230, D232, and D238 at C2A and D303, D309, D363, D365, and D371 at C2B. Interestingly, our simulations also demonstrated that these residues are never simultaneously involved in coordination with Ca2+ ions. Instead, some of the aspartates formed several stable coordination bonds, whereas other aspartic acids formed transient bonds. For example, residues D230 and D238 of C2A domain formed stable coordination bonds, whereas other aspartates alternated in forming transient interactions. The latter finding can explain apparent controversies in structural studies, such as lack of involvement of D371 in Ca2+ chelation observed by crystallography (44). Furthermore, the flexibility in Ca2+ coordination could facilitate Syt1 interaction with lipids. A recent study (45) provides one such example, showing that residue D309 interacts both with Ca2+ and phophatidylserine.

Notably, our simulations closely reproduced stoichiometry of Ca2+ binding for the isolated C2B domain (14) but not for the isolated C2A domain (15), because only two Ca2+ ions were chelated at the C2A-binding pocket in our simulations. This result is in line with an earlier biochemical study (22), and it suggests that C2 domain interaction is likely to affect Syt1 Ca2+-binding properties.

Of importance, we found that the ensemble of Syt1 conformational states is significantly altered upon chelating Ca2+ ions. Our simulations demonstrated that in the Ca2+-bound form, C2 domains are not tightly coupled, and they separate frequently creating configurations with a stretched linker. Respectively, domains rotate more freely and conformational transitions occur more frequently for the Ca2+-bound form of Syt1.

It should be noted that Syt1 is attached to a synaptic vesicle via its transmembrane domain, and therefore configuration and dynamics of C2 domains may be influenced by their proximity to the vesicle membrane. Furthermore, once the vesicle is docked, Syt1 becomes positioned within a relatively narrow gap between the vesicle and the plasma membrane, and its domains may interact with both membranes. Our findings have important implications for understanding the dynamic of this process and for elucidating the mechanisms of synaptic vesicle fusion triggered by the inflow of calcium and its chelation by Syt1.

Indeed, numerous studies suggest that coordinated insertion of the tips of C2 domains into phospholipids mediate synaptic vesicle docking and fusion (reviewed in (8)). For example, a model was proposed (46) whereby the tips of C2 domains insert into the plasma membrane upon Ca2+ binding and thus create a membrane tension required to open the fusion pore (47). Such model implies that Ca2+-binding pockets of C2 domains would face the same surface. Our MD simulations suggest that such a conformational state would not be stable for the Ca2+-unbound form of Syt1; however, Ca2+ binding would promote domain rotations and thus increase the likelihood for the appropriate domain configuration to occur. These findings suggests that Ca2+ binding, besides neutralizing the negative charge of Ca2+-binding loops and enabling their insertion into lipids, also accelerates a transition into the conformational state with Ca2+-binding pockets facing the same surface. Such a scenario could explain the observation that the release process slows down upon neutralization of the aspartic acids chelating Ca2+ at C2A domain (20).

In addition to opening the fusion pore, Syt1 is thought to mediate synaptic vesicle docking (6,48–50), possibly through bridging two opposing membranes (9,22,45,51). The latter model implies that Syt1 adopts a conformation with Ca2+-binding pockets of C2 domains facing opposite surfaces (9,51). Our simulations demonstrated that one of the stable and highly populated Syt1 conformers (state C2, Fig. 3) satisfies this condition. When Syt1 adopts C2 conformation, the distance between its Ca2+-binding pockets equals ∼5 nm. Because electrostatic repulsion between bilayers becomes prominent at a distance of 2–3 nm (52), it is a plausible scenario that Syt1 adopts the state with opposing Ca2+-binding pockets, bridges the membranes, and brings bilayers at a distance where electrostatic repulsion becomes prominent (6). Initially, charged residues of Ca2+-binding loops may interact with lipids (53), and subsequently Ca2+ chelation would promote a further insertion of domain tips into lipids. Such bridging of bilayers could occur in cooperation with partial SNARE zippering (11,54,55).

Thus, the results of our simulations shed light on the overall dynamics of multifaceted Syt1 function in the release process. Syt1 is thought to act at multiple stages of Ca2+-dependent exocytosis (reviewed in (7,8)) including synaptic vesicles docking, possibly fusion clamping (56,57), and triggering fusion upon Ca2+ inflow. Our simulations, within the framework of earlier studies of Syt1 structure, dynamics, and function, suggest a plausible scenario for Syt1 multistep action in the fusion process. Syt1 may adopt a stable and highly populated state with Ca2+-binding pockets facing opposite surfaces and initiate bridging the synaptic membrane and the vesicle via the interactions of charged residues of Ca2+-binding loops with lipids. Next, Ca2+ elevation, such as residual Ca2+ or Ca2+ released from internal stores (reviewed in (58)) would promote Ca2+-bound Syt1 form and respectively induce deeper insertion of domain tips into lipid bilayers. This stage may be associated with an interaction between Syt1 and the SNARE complex, partial SNARE zippering, and a transition of Syt1 into a different conformational state. Subsequently, Ca2+ ions may dissociate from Syt1 thus causing a stabilization of the Syt1 conformational state, which may then contribute to a fusion clamp within the primed prefusion complex. Subsequently, Ca2+ influx triggered by an action potential would induce Ca2+ chelation by Syt1 followed by an enhanced conformational flexibility of Syt1, a conformational transition, and insertion of Ca2+-binding pockets into the plasma membrane, creating a membrane tension and triggering fusion.

Author Contributions

M.B. designed and performed research, analyzed data, and wrote the article.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. J. Troy Littleton and Anand Jagota for productive discussions. Simulations were performed at Anton supercomputer (D. E. Show Research and Pittsburg Supercomputer Center) and XSEDE resources (Stampede supercomputer at TACC).

This study was supported by grant R01 099557 from the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH).

Supporting Material

References

- 1.Brose N., Petrenko A.G., Jahn R. Synaptotagmin: a calcium sensor on the synaptic vesicle surface. Science. 1992;256:1021–1025. doi: 10.1126/science.1589771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Geppert M., Goda Y., Südhof T.C. Synaptotagmin I: a major Ca2+ sensor for transmitter release at a central synapse. Cell. 1994;79:717–727. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90556-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Littleton J.T., Stern M., Bellen H.J. Calcium dependence of neurotransmitter release and rate of spontaneous vesicle fusions are altered in Drosophila synaptotagmin mutants. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1994;91:10888–10892. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.23.10888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fernández-Chacón R., Königstorfer A., Südhof T.C. Synaptotagmin I functions as a calcium regulator of release probability. Nature. 2001;410:41–49. doi: 10.1038/35065004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yoshihara M., Littleton J.T. Synaptotagmin I functions as a calcium sensor to synchronize neurotransmitter release. Neuron. 2002;36:897–908. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)01065-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jahn R., Fasshauer D. Molecular machines governing exocytosis of synaptic vesicles. Nature. 2012;490:201–207. doi: 10.1038/nature11320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Südhof T.C. Neurotransmitter release: the last millisecond in the life of a synaptic vesicle. Neuron. 2013;80:675–690. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.10.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chapman E.R. How does synaptotagmin trigger neurotransmitter release? Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2008;77:615–641. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.77.062005.101135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Herrick D.Z., Kuo W., Cafiso D.S. Solution and membrane-bound conformations of the tandem C2A and C2B domains of synaptotagmin 1: evidence for bilayer bridging. J. Mol. Biol. 2009;390:913–923. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2009.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.de Wit H., Walter A.M., Verhage M. Synaptotagmin-1 docks secretory vesicles to syntaxin-1/SNAP-25 acceptor complexes. Cell. 2009;138:935–946. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.07.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Parisotto D., Malsam J., Söllner T.H. SNAREpin assembly by Munc18-1 requires previous vesicle docking by synaptotagmin 1. J. Biol. Chem. 2012;287:31041–31049. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.386805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Imig C., Min S.W., Cooper B.H. The morphological and molecular nature of synaptic vesicle priming at presynaptic active zones. Neuron. 2014;84:416–431. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2014.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Perin M.S., Brose N., Südhof T.C. Domain structure of synaptotagmin (p65) J. Biol. Chem. 1991;266:623–629. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ubach J., Zhang X., Rizo J. Ca2+ binding to synaptotagmin: how many Ca2+ ions bind to the tip of a C2-domain? EMBO J. 1998;17:3921–3930. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.14.3921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fernandez I., Araç D., Rizo J. Three-dimensional structure of the synaptotagmin 1 C2B-domain: synaptotagmin 1 as a phospholipid binding machine. Neuron. 2001;32:1057–1069. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00548-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Littleton J.T., Bai J., Chapman E.R. synaptotagmin mutants reveal essential functions for the C2B domain in Ca2+-triggered fusion and recycling of synaptic vesicles in vivo. J. Neurosci. 2001;21:1421–1433. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-05-01421.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mackler J.M., Drummond J.A., Reist N.E. The C(2)B Ca(2+)-binding motif of synaptotagmin is required for synaptic transmission in vivo. Nature. 2002;418:340–344. doi: 10.1038/nature00846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nishiki T., Augustine G.J. Dual roles of the C2B domain of synaptotagmin I in synchronizing Ca2+-dependent neurotransmitter release. J. Neurosci. 2004;24:8542–8550. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2545-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stevens C.F., Sullivan J.M. The synaptotagmin C2A domain is part of the calcium sensor controlling fast synaptic transmission. Neuron. 2003;39:299–308. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00432-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yoshihara M., Guan Z., Littleton J.T. Differential regulation of synchronous versus asynchronous neurotransmitter release by the C2 domains of synaptotagmin 1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2010;107:14869–14874. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1000606107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Striegel A.R., Biela L.M., Reist N.E. Calcium binding by synaptotagmin’s C2A domain is an essential element of the electrostatic switch that triggers synchronous synaptic transmission. J. Neurosci. 2012;32:1253–1260. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4652-11.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Radhakrishnan A., Stein A., Fasshauer D. The Ca2+ affinity of synaptotagmin 1 is markedly increased by a specific interaction of its C2B domain with phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate. J. Biol. Chem. 2009;284:25749–25760. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.042499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fuson K.L., Montes M., Sutton R.B. Structure of human synaptotagmin 1 C2AB in the absence of Ca2+ reveals a novel domain association. Biochemistry. 2007;46:13041–13048. doi: 10.1021/bi701651k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Choi U.B., Strop P., Weninger K.R. Single-molecule FRET-derived model of the synaptotagmin 1-SNARE fusion complex. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2010;17:318–324. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Araç D., Chen X., Rizo J. Close membrane-membrane proximity induced by Ca(2+)-dependent multivalent binding of synaptotagmin-1 to phospholipids. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2006;13:209–217. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Huang H., Cafiso D.S. Conformation and membrane position of the region linking the two C2 domains in synaptotagmin 1 by site-directed spin labeling. Biochemistry. 2008;47:12380–12388. doi: 10.1021/bi801470m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bai J., Wang P., Chapman E.R. C2A activates a cryptic Ca(2+)-triggered membrane penetration activity within the C2B domain of synaptotagmin I. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2002;99:1665–1670. doi: 10.1073/pnas.032541099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hui E., Bai J., Chapman E.R. Ca2+-triggered simultaneous membrane penetration of the tandem C2-domains of synaptotagmin I. Biophys. J. 2006;91:1767–1777. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.105.080325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liu H., Bai H., Chapman E.R. Linker mutations reveal the complexity of synaptotagmin 1 action during synaptic transmission. Nat. Neurosci. 2014;17:670–677. doi: 10.1038/nn.3681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fealey M.E., Gauer J.W., Hinderliter A. Negative coupling as a mechanism for signal propagation between C2 domains of synaptotagmin I. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e46748. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0046748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Augustine G.J., Charlton M.P., Smith S.J. Calcium entry and transmitter release at voltage-clamped nerve terminals of squid. J. Physiol. 1985;367:163–181. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1985.sp015819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sabatini B.L., Regehr W.G. Timing of neurotransmission at fast synapses in the mammalian brain. Nature. 1996;384:170–172. doi: 10.1038/384170a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lisman J.E., Raghavachari S., Tsien R.W. The sequence of events that underlie quantal transmission at central glutamatergic synapses. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2007;8:597–609. doi: 10.1038/nrn2191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li Z., Scheraga H.A. Monte Carlo-minimization approach to the multiple-minima problem in protein folding. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1987;84:6611–6615. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.19.6611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tikhonov D.B., Zhorov B.S. Architecture and pore block of eukaryotic voltage-gated sodium channels in view of NavAb bacterial sodium channel structure. Mol. Pharmacol. 2012;82:97–104. doi: 10.1124/mol.112.078212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shaw, D. E., R. O. Dror, …, B. Towles. 2009. Millisecond-scale molecular dynamics simulations on Anton. Proceedings of the Conference on High Performance Computing, Networking, Storage and Analysis SC09. New York, ACM. Ref Type: Generic.

- 37.Phillips J.C., Braun R., Schulten K. Scalable molecular dynamics with NAMD. J. Comput. Chem. 2005;26:1781–1802. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mackerell A.D., Jr. Empirical force fields for biological macromolecules: overview and issues. J. Comput. Chem. 2004;25:1584–1604. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shao X., Fernandez I., Rizo J. Solution structures of the Ca2+-free and Ca2+-bound C2A domain of synaptotagmin I: does Ca2+ induce a conformational change? Biochemistry. 1998;37:16106–16115. doi: 10.1021/bi981789h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gauer J.W., Sisk R., Hinderliter A. Mechanism for calcium ion sensing by the C2A domain of synaptotagmin I. Biophys. J. 2012;103:238–246. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2012.05.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wu Z., Schulten K. Synaptotagmin’s role in neurotransmitter release likely involves Ca(2+)-induced conformational transition. Biophys. J. 2014;107:1156–1166. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2014.07.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lai A.L., Huang H., Cafiso D.S. Synaptotagmin 1 and SNAREs form a complex that is structurally heterogeneous. J. Mol. Biol. 2011;405:696–706. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2010.11.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Krishnakumar S.S., Kümmel D., Rothman J.E. Conformational dynamics of calcium-triggered activation of fusion by synaptotagmin. Biophys. J. 2013;105:2507–2516. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2013.10.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cheng Y., Sequeira S.M., Patel D.J. Crystallographic identification of Ca2+ and Sr2+ coordination sites in synaptotagmin I C2B domain. Protein Sci. 2004;13:2665–2672. doi: 10.1110/ps.04832604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Honigmann A., van den Bogaart G., Jahn R. Phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate clusters act as molecular beacons for vesicle recruitment. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2013;20:679–686. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Paddock B.E., Striegel A.R., Reist N.E. Ca2+-dependent, phospholipid-binding residues of synaptotagmin are critical for excitation-secretion coupling in vivo. J. Neurosci. 2008;28:7458–7466. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0197-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Martens S., Kozlov M.M., McMahon H.T. How synaptotagmin promotes membrane fusion. Science. 2007;316:1205–1208. doi: 10.1126/science.1142614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wang Z., Liu H., Chapman E.R. Reconstituted synaptotagmin I mediates vesicle docking, priming, and fusion. J. Cell Biol. 2011;195:1159–1170. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201104079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kim J.Y., Choi B.K., Lee N.K. Solution single-vesicle assay reveals PIP2-mediated sequential actions of synaptotagmin-1 on SNAREs. EMBO J. 2012;31:2144–2155. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2012.57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lai Y., Lou X., Shin Y.K. The synaptotagmin 1 linker may function as an electrostatic zipper that opens for docking but closes for fusion pore opening. Biochem. J. 2013;456:25–33. doi: 10.1042/BJ20130949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kuo W., Herrick D.Z., Cafiso D.S. Phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate alters synaptotagmin 1 membrane docking and drives opposing bilayers closer together. Biochemistry. 2011;50:2633–2641. doi: 10.1021/bi200049c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bykhovskaia M., Jagota A., Littleton J.T. Interaction of the complexin accessory helix with the C-terminus of the SNARE complex: molecular-dynamics model of the fusion clamp. Biophys. J. 2013;105:679–690. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2013.06.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wang P., Wang C.T., Chapman E.R. Mutations in the effector binding loops in the C2A and C2B domains of synaptotagmin I disrupt exocytosis in a nonadditive manner. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:47030–47037. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M306728200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Walter A.M., Wiederhold K., Sørensen J.B. Synaptobrevin N-terminally bound to syntaxin-SNAP-25 defines the primed vesicle state in regulated exocytosis. J. Cell Biol. 2010;188:401–413. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200907018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zorman S., Rebane A.A., Zhang Y. Common intermediates and kinetics, but different energetics, in the assembly of SNARE proteins. eLife. 2014;3:e03348. doi: 10.7554/eLife.03348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wang C.T., Lu J.C., Jackson M.B. Different domains of synaptotagmin control the choice between kiss-and-run and full fusion. Nature. 2003;424:943–947. doi: 10.1038/nature01857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Chicka M.C., Hui E., Chapman E.R. Synaptotagmin arrests the SNARE complex before triggering fast, efficient membrane fusion in response to Ca2+ Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2008;15:827–835. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kaeser P.S., Regehr W.G. Molecular mechanisms for synchronous, asynchronous, and spontaneous neurotransmitter release. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2014;76:333–363. doi: 10.1146/annurev-physiol-021113-170338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.