Abstract

Introduction and hypothesis

There has been increasing media attention regarding transvaginal mesh (TVM). We hypothesized that new urogynecology patients have limited knowledge and negative opinions of TVM.

Methods

An anonymous survey was distributed to all new patients presenting to the Mt Auburn Hospital urogynecology practice from 1 November 2012 to 31 January 2013. A total of 146 patients completed the questionnaire. The survey was designed to elicit information on participants’ knowledge and opinions about TVM and knowledge about recent FDA safety communications. All statistical tests were two-sided, and P values <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Analyses were restricted to the 77 women who had either heard of TVM or were unsure if they had heard of TVM. A minority (32.5 %) of these women correctly defined TVM, and 33.8 % had a negative impression of TVM. Respondents obtained their information on TVM from the media (48.1 %), the Internet (24.7 %), family or friends (22.1 %), and health care providers (18.2 %). The majority (71.4 %) agreed that they needed more information about TVM before making any decisions about using it to treat their condition. Nearly one quarter of respondents (23.4 %) agreed that they would not want their doctor to use TVM on them for any reason. When asked about recent FDA communications, 27.3 % of patients correctly responded that the FDA had released a safety communication regarding TVM.

Conclusions

The majority of participants had limited knowledge of TVM; however, only a minority had negative opinions. Given our findings, it is important that providers spend more time during the consent process explaining TVM and its risks and benefits as a treatment option.

Keywords: Pelvic organ prolapse, Transvaginal mesh

Introduction

Pelvic organ prolapse is among the most common gynecological conditions experienced by women. Approximately 40 % of women develop some form of pelvic organ prolapse during the course of their lifetime, and it is estimated that 11–19 % of all women will undergo a surgical procedure for the treatment of pelvic organ prolapse [1–3].

Surgeons often elect to use synthetic, non-absorbable materials to augment, or reinforce, a prolapse repair. A recent study found that about 23.8 % of women over the age of 18 who underwent pelvic organ prolapse repair had a mesh-augmented repair [4]. While the literature on the use of transvaginal mesh is limited, several prospective studies have demonstrated that synthetic, non-absorbable material decreases the incidence of prolapse recurrence in the anterior compartment compared with native tissue repairs [5–7].

Although transvaginal mesh (TVM) has been associated with low rates of prolapse recurrence in comparison with some native tissue procedures, several complications are associated with TVM, including mesh exposure, de novo dyspareunia, and higher rates of reoperation compared with native tissue repair [8, 9]. In 2008, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) released a public health notification, which cited over 1,000 manufacturers’ reports of complications [10]. This notification was followed by a safety update in 2011 to inform health care providers and patients that serious complications following surgical repair of pelvic organ prolapse with TVM are not rare. The FDA also reported that it is not clear whether or not pelvic organ prolapse repair with TVM is more effective than non-mesh repairs. This update was based on an additional 2,874 reports of complications associated with surgical mesh devices used to repair pelvic organ prolapse and stress urinary incontinence received by the FDA from 2008 to 2010, and on their review of the literature [11].

Since the release of the FDA safety communications, there has been an increase in litigation over TVM complications. The negative press and advertisements from legal agencies has likely affected patient perceptions regarding synthetic mesh. Given the recent deluge of media attention, a discussion of mesh has become a more prominent part of the informed consent process between physicians and patients seeking treatment for pelvic organ prolapse.

While some surgeons have stopped using TVM in their practices, others recognize that mesh can still be a highly effective method of treating pelvic organ prolapse in appropriately selected patients. Thus, it is important to understand patients’ knowledge of and feelings about TVM in the wake of the FDA safety reports and negative media attention. We undertook this study in order to develop a preliminary understanding of attitudes toward and sources of information about TVM among new urogynecology patients presenting to our practice.

Materials and methods

We conducted a cross-sectional pilot-study at the Mount Auburn Hospital Urogynecology clinic, utilizing a sample of convenience. Given our patient volume, it was determined that a 3-month period would be long enough to see a representative sample of our patient population; thus, data were collected from 1 November 2012 to 31 January 2013. New patients over the age of 18, presenting with one or more complaints consistent with a pelvic floor disorder, and able to speak and read English, were eligible for participation in this study. The Mount Auburn Hospital institutional review board approved the study prior to its initiation.

After they were placed in an examination room, all eligible patients were approached by a medical assistant and given a written explanation of the study. After reading the document, patients were asked if they would be willing to participate in the study, and verbal consent was obtained by the medical assistant. No data were collected on patients who declined to participate in the study.

After verbal consent was obtained, participants were given a questionnaire to complete anonymously, before being seen by the provider. The questionnaire had been pilot-tested with residents, fellows, attendings, and nursing staff for readability. This questionnaire included basic demographic information, as well as questions regarding the reason for the visit, sexual activity, and surgical history of prolapse or incontinence procedures. Participants who had a history of surgical repair for prolapse or incontinence were asked if their repair used mesh and if so, whether they had experienced any problems with the mesh. In order to capture the knowledge and attitudes held by our patients about TVM, participants were asked about the definition of TVM, the source of their information, and their opinion on TVM. Participants were also questioned about their knowledge of the recent FDA safety communication. Finally, patients were asked about their daily television and Internet usage, in order to assess their exposure to news and advertisements from legal groups. Opinion questions were asked on either a 10-point scale, with 0 being an extremely negative impression, less than 5 a negative impression, 5 a neutral impression, greater than 5 a positive impression, and 10 an extremely positive impression, or a Likert scale with five values ranging from “Disagree” to “Agree” (Appendix).

Categorical data were compared using a Chi-squared or Fisher’s exact test; ordinal and continuous data were compared using the Wilcoxon rank sum test. Data are presented as median (interquartile range) or proportions. The Spearman correlation coefficient was used to assess the relationship between impressions of TVM and the number of hours spent on the Internet or watching TV each day. Given the objective of our study, all analyses beyond demographics and history of prolapse repair were restricted to the 77 participants who had either heard of TVM or were unsure of whether they had heard of TVM. All analyses were performed using SAS 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA). All tests were two-sided, and P values<0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

A total of 146 patients completed questionnaires. Sixty-five women (44.5 %) had heard of TVM, and an additional 12 (8.2 %) were unsure. The median age of respondents was 51.0 years (38.5–65.5). The most common reasons for presentation at the clinic were urinary leakage (41.0 %), followed by bulge symptoms (30.8 %). and thirdly pain (26.0 %). A significantly higher percentage of patients presenting for bulge symptoms had heard of transvaginal mesh than those who were presenting for other reasons (P=0.0002). Patients presenting for pain were not more likely to report “yes” to having heard of transvaginal mesh than those presenting for other reasons (P=1.0). Twenty-three patients (15.8 %) reported having undergone previous prolapse repair surgery and 11 (47.8 %) of those reported repair with TVM. Participants who had previously received mesh as a treatment for pelvic organ prolapse were more likely to have heard of TVM or to be unsure of whether they had heard of TVM (P<0.01) than those who had not received previous treatment with mesh for pelvic organ prolapse. There was no significant difference between participants who had or were unsure if they had heard of TVM, and those who had not heard of TVM in terms of race (P=0.07) or educational status (P=0.7; Table 1).

Table 1.

Participant characteristics

| Characteristic | Had heard of mesh or unsure if heard of transvaginal mesh (N=77) |

Had not heard of transvaginal mesh (N=62) |

P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years, median (interquartile range) | 55.5 (43.5–64.0005) | 40.0 (31.0–64.0) | 0.005 |

| Race/ethnicity. n (%) | 0.063 | ||

| Caucasian | 68 (89.3) | 52 (83.9) | |

| African–American | 2 (2.6) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Hispanic | 5 (6.5) | 2 (3.2) | |

| Asian | 0 (0.0) | 4 (6.5) | |

| Other | 2 (2.6) | 4 (6.5) | |

| Education. n (%) | 0.78 | ||

| Elementary school or less | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.6) | |

| High school | 9 (11.7) | 7 (11.3) | |

| Some college | 12 (15.6) | 7 (11.3) | |

| College | 26 (33.8) | 19 (30.7) | |

| Graduate school or more | 30 (39.0) | 28 (45.2) | |

| Previous surgical treatment for pelvic organ prolapse. n (%) | 0.002 | ||

| No | 56 (74.7) | 57 (95.0) | |

| Yes | 19 (25.3) | 3 (5.0) | |

| Hours of internet use. n (%) | 0.76 | ||

| 0 to <1 | 24 (31.2) | 17 (27.9) | |

| 1 to <2 | 20 26.0) | 16 (26.2) | |

| 2 to <3 | 16 (20.8) | 10 (16.4) | |

| 3 to <4 | 7 (9.1) | 5 (8.2) | |

| ≥4 | 10 (13.0) | 13 (21.3) | |

Participants who did not respond to the question were excluded from analyses

The following analyses are restricted to the 77 respondents who had heard of or were unsure if they had heard of TVM. When asked to define TVM, only a minority of participants (32.5 %) correctly defined it as mesh placed through an incision in the vagina for prolapse, while almost half of participants (44.9 %) were not sure how to define TVM. Approximately one third (33.8 %) of participants had a negative impression of TVM. Respondents had obtained their information on TVM from the media (48.1 %), the Internet (24.7 %), family or friends (22.1 %), and health care providers (18.2 %).

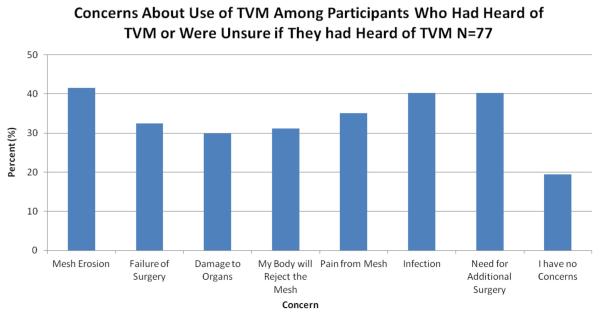

When asked if they would not want their doctor to use TVM as a treatment option, nearly one quarter of respondents (24.7 %) agreed that they would not want their doctor to use TVM for any reason. Participants were also asked if they felt that they needed more information about TVM before drawing a conclusion about its use as a treatment option, and the majority of participants (71.4 %) agreed that they needed more information about TVM before drawing any conclusions. Additionally, 44.2 % of participants felt that TVM might be appropriate in some situations for the treatment of prolapse. The most common concerns regarding TVM included mesh erosion (41.6 %), infection (40.3 %), and the need for additional surgery (40.3 %; Fig. 1). When asked about the recent FDA safety communications, 27.3 % of patients correctly responded that the FDA had released a safety communication regarding TVM and 62.3 % were unsure if they had heard about the safety communication. Most of the participants (74.0 %) were unsure about whether the FDA had recalled any TVM products.

Fig. 1.

Participant concerns about transvaginal mesh (TVM)

Caucasian women had a more favorable impression of mesh than non-Caucasian women (5.0 [3.0–5.0] vs 2.0 [0.0–5.0], P=0.03). There was no difference in impression among women who had completed at least a bachelor’s degree compared with those who had not (P=0.94) or among women who were >65 years of age compared with those who were ≤65 years of age (P=0.43). There was no difference in impression among patients who reported having undergone a previous procedure with TVM for prolapse compared with those without a history of such procedures (P=0.09). Similarly, hours of television and Internet use did not correlate with opinion regarding TVM (P=0.52 and P=0.39; Table 2).

Table 2.

Opinions of transvaginal mesh (TVM)

| Characteristic | Number of responses, n (%) |

Opinion of TVM, median (interquartile range)a |

P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Race | 0.03 | ||

| Caucasian | 62 (89.9) | 5.0 (3.0-5.0) | |

| Non-Caucasians | 7 (10.1) | 2.0 (0.0-5.0) | |

| Age | 0.43 | ||

| >65 | 14 (20.6) | 5.0 (2.0-5.0) | |

| ≤65 | 54 (79.4) | 5.0 (5.0-5.0) | |

| Education | 1.0 | ||

| Bachelor’s degree or higher | 50 (72.5) | 5.0 (2.0-5.0) | |

| Less than a Bachelor’s degree | 19 (27.5) | 5.0 (2.0-5.0) | |

| Previous surgical treatment for pelvic organ prolapse | 0.94 | ||

| Yes | 19 (28.4) | 5.0 (5.0-6.0) | |

| No | 48 (71.6) | 5.0 (1.0-5.0) | |

Participants rated their opinion of TVM on a scale from 0 to 10. Scores of 0–4 were negative impressions of TVM, 5 was a neutral impression of TVM, and 6–10 were positive impressions of TVM

Discussion

Findings from this study show that despite recent negative attention from the media, a significant portion of participants had never heard of TVM. The majority of participants incorrectly defined TVM, and stated that they needed more information before forming any opinions regarding its use in their treatment. Additionally, the majority of participants were unsure of the FDA’s position regarding TVM. Among women who had heard of TVM or were unsure if they had heard of TVM, the majority had obtained their information from the media and the Internet. Despite the fact that participants learned about TVM from these sources, use of television or Internet did not correlate with patients’ opinions about TVM.

Research has shown that the FDA safety communication has had an impact on providers’ usage of TVM [12, 13]. A survey of 507 members of the American Urogynecology Society conducted by Clemons et al. found that TVM use had decreased by 40 % among providers since the 2011 FDA safety update [14]. Providers, however, have not stopped treating pelvic organ prolapse with TVM. Although the American Congress of Obstetrics and Gynecology currently recommends that the use of TVM repairs be restricted to high-risk individuals in whom the benefit of decreased recurrence in the anterior compartment outweighs the potentially increased risks, it has not recommended that providers stop using TVM altogether [12, 15]. Our study shows that patients will be willing to consider TVM for the treatment of their condition if their provider feels that TVM is appropriate. These findings indicate that providers may not need to alter their practices based on perceived patient attitudes.

Our study also draws further attention to the fact that better communication around TVM is needed between providers and patients. Following the 2008 FDA notification, Mucowski et al. published a commentary on the current medical–legal controversies and the importance of informed consent when using TVM [12]. The authors discussed how physicians can best protect themselves from litigation by choosing appropriate patients for the use of TVM for pelvic organ prolapse repair and conducting a thorough consenting process. Similar to other literature in this area, the authors focused on the impact of the FDA notifications on providers rather than on patients [12, 13]. Our study extends this body of research by showing that better communication is also necessary to help patients understand what TVM is and why it may be the appropriate treatment option for their condition.

This pilot study has several strengths, including the anonymous survey responses. Patients were also asked to complete the questionnaire before being seen by a provider to limit any influence by surgeons’ preference. There are, however, several limitations. Our study population was predominantly older, educated, and Caucasian; therefore, the generalizability of our findings may be limited to similar patient populations. Although we only included patients who presented with a pelvic floor disorder, we sought to obtain a global view of patients’ attitudes toward TVM; thus, we did not restrict inclusion to a specific pelvic floor disorder or age range. Additionally, although we tested our questionnaire for reliability, we used a nonvalidated questionnaire, given that no validated questionnaires on this topic exist to our knowledge.

Although it is unclear if the recent decrease in TVM use for pelvic organ prolapse is patient or provider driven, patients’ knowledge, or lack of knowledge, about this method of treatment is important for providers to understand when counseling patients regarding their surgical options. As the number of patients undergoing surgical correction for prolapse—both with and without synthetic mesh—is increasing, and repair with TVM can be highly effective in preventing recurring prolapse, TVM will likely continue to be a treatment option for pelvic organ prolapse [16]. Our study demonstrates that a significant portion of our patient population has misconceptions about TVM, and about the FDA communications regarding TVM. For this reason, it may be beneficial for providers to proactively provide information on TVM to patients who are presenting to urogynecology offices with pelvic floor problems.

Acknowledgments

Sources of financial support Harvard Catalyst, the Harvard Clinical and Translational Science Center (NIH Award #UL1 RR 025758 and financial contributions from Harvard University and its affiliated academic health care centers).

Appendix

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest Dr. Rosenblatt is a consult for American Medical Systems, Bard, Boston Scientific, Coloplast and Ethicon. He receives research funding from Boston Scientific and Coloplast and has a licensing agreement with for American Medical Systems.

Contributor Information

Sybil G. Dessie, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, MA, USA; Department of Obstetrics, Gynecology and Reproductive Biology, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, USA; Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Mount Auburn Hospital, Cambridge, MA, USA; Boston Urogynecology Associates, Mount Auburn Hospital, 725 Concord Avenue, Suite 1200, Cambridge, MA 02138, USA

Michele R. Hacker, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, MA, USA; Department of Obstetrics, Gynecology and Reproductive Biology, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, USA; Department of Epidemiology, Harvard School of Public Health, Boston, MA, USA

Miriam J. Haviland, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, MA, USA

Peter L. Rosenblatt, Department of Obstetrics, Gynecology and Reproductive Biology, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, USA; Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Mount Auburn Hospital, Cambridge, MA, USA

References

- 1.Olsen AL, Smith VJ, Bergstrom JO, et al. Epidemiology of surgically managed pelvic organ prolapse and urinary incontinence. Obstet Gynecol. 1997;89:501–506. doi: 10.1016/S0029-7844(97)00058-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Smith FJ, Holman CD, Moorin RE, et al. Lifetime risk of undergoing surgery for pelvic organ prolapse. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;116:1096–1100. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181f73729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hendrix SL, Clark A, Nygaard I, et al. Pelvic organ prolapse in the Women’s Health Initiative: gravity and gravidity. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;186:1160–1166. doi: 10.1067/mob.2002.123819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rogo-Gupta L, Rodriguez LV, Litwin MS, et al. Trends in surgical mesh use for pelvic organ prolapse from 2000 to 2010. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;120:1105–1115. doi: 10.1097/aog.0b013e31826ebcc2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hiltunen R, Nieminen K, Takala T, et al. Low-weight polypropylene mesh for anterior vaginal wall prolapse: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;110:455–462. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000261899.87638.0a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Julian TM, Grody T. The efficacy of Marlex mesh in the repair of severe, recurrent vaginal prolapse of the anterior midvaginal wall. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1996;175:1472–1475. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(96)70092-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bai SW, Jung HJ, Jeon MJ, et al. Surgical repair of anterior wall vaginal defects. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2007;98:147–150. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2007.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maher C, Feiner B, Baessler K, et al. Surgical management of pelvic organ prolapse in women (review) Cochrane Database Sys Rev. 2013;(3) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004014.pub5. CD004014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Iglesia CB. Synthetic vaginal mesh for pelvic organ prolapse. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2011;23:362–365. doi: 10.1097/GCO.0b013e32834a92ab. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. [Accessed 11 November 2014];FDA Public Health Notification: serious complications associated with transvaginal placement of surgical mesh in repair of pelvic organ prolapse and stress urinary incontinence. 2008 Oct 20; doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2009.01.055. Available at: http://www.fda.gov/MedicalDevices/Safety/AlertsandNotices/PublicHealthNotifications/ucm061976.htm. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11. [Accessed 11 November 2014];FDA Safety Communication: update on serious complications associated with transvaginal placement of surgical mesh for pelvic organ prolapse. 2011 Jul 13; doi: 10.1007/s00192-011-1581-2. Available at: http://www.fda.gov/MedicalDevices/Safety/AlertsandNotices/ucm262435.htm. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Mucowski SJ, Jurnalov C, Phelps JY, et al. Use of vaginal mesh in the face of recent FDA warnings and litigation. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;203:103e.1–103e.4. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2010.01.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gomelsky A, Dmochowski RR. Vaginal mesh update. Curr Opin Urol. 2012;22:271–275. doi: 10.1097/MOU.0b013e3283548051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Clemons JL, Weinstein M, Guess MK, et al. Impact of the 2011 FDA transvaginal mesh safety update on AUGS members’ use of synthetic mesh and biologic grafts in pelvic reconstructive surgery. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2013;194:191–196. doi: 10.1097/SPV.0b013e31829099c1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee opinion no. 513: vaginal placement of synthetic mesh for pelvic organ prolapse. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;118:1459–1464. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31823ed1d9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Reynolds WS, Gold KP, Ni S, et al. Immediate effects of the initial FDA notification on the use of surgical mesh for pelvic organ prolapse surgery in Medicare beneficiaries. Neurourol Urodyn. 2013;32:330–335. doi: 10.1002/nau.22318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]