Abstract

Prior research has shown insight deficits in schizophrenia to be associated with specific neuroimaging changes (primarily structural) especially in the prefrontal sub-regions. However, little is known about the functional correlates of impaired insight. Seventeen patients with schizophrenia (mean age 40.0±10.3; M/F= 14/3) underwent fMRI on a Philips 3.0 T Achieva system while performing on a self-awareness task containing self- vs. other-directed sentence stimuli. SPM5 was used to process the imaging data. Preprocessing consisted of realignment, coregistration, and normalization, and smoothing. A regression analysis was used to examine the relationship between brain activation in response to self-directed versus other-directed sentence stimuli and average scores on behavioral measures of awareness of symptoms and attribution of symptoms to the illness from Scale to Assess Unawareness of Mental Disorders. Family Wise Error correction was employed in the fMRI analysis. Average scores on awareness of symptoms (1 = aware; 5 = unaware) were associated with activation of multiple brain regions, including prefrontal, parietal and limbic areas as well as basal ganglia. However, average scores on correct attribution of symptoms (1 = attribute; 5 = misattribute) were associated with relatively more localized activation of prefrontal cortex and basal ganglia. These findings suggest that unawareness and misattribution of symptoms may have different neurobiological basis in schizophrenia. While symptom unawareness may be a function of a more complex brain network, symptom misattribution may be mediated by specific brain regions.

Keywords: neurobiology, insight, deficits, schizophrenia, fMRI

1. Introduction

Impaired insight into illness is one of the most frequently observed phenomena in schizophrenia (Sartorius et al. 1972), which has been associated with multiple clinical outcome measures such as treatment nonadherence (David et al., 1992; McEvoy et al., 1989; Perkins, 2002), poor psychosocial functioning (Amador et al., 1994; Dickerson et al., 1997), premorbid functional impairment (Debowska et al., 1998), poor prognosis (Rosen and Garety, 2005; Schwartz et al., 1997), involuntary hospitalizations (Kelly et al., 2004), and higher utilization of emergency services (Haro et al., 2001). However, despite its clinical significance, little is known about the neurobiological correlates of insight deficits in schizophrenia. Nevertheless, findings from neurocognitive and imaging studies (primarily structural) suggest involvement of midline and lateral cortical structures in mediation of insight deficits in schizophrenia (Antonius et al. 2011, Berge et al. 2011, Buchy et al. 2011, Buchy et al. 2012, Cooke et al. 2008; Flashman et al. 2001; Morgan et al. 2010, Shad et al. 2004, Shad et al. 2006; Shad et al. 2012b).

These studies have shown grey matter reductions in prefrontal and temporal cortices (Berge et al. 2011; Cooke et al. 2008) and precuneus and parietal cortex (Cooke et al. 2008) in patients with insight deficits. In addition, Buchy et al. (2011) observed cortical thinning in the middle, inferior and medial frontal gyri, temporal gyri and precuneus in patients with insight deficits during first episode psychosis. The same group reported cortical thickness in the orbitofrontal cortex (OFC) and thinness in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) in association with misattribution of symptoms (Buchy et al. 2012). It is interesting that Shad and Colleagues (2006) also reported larger OFC and smaller DLPFC volumes in association with misattribution of symptoms in patients with first-episode schizophrenia. In an earlier study, Flashman et al. (2001) found a differential structural relationship with the two insight dimensions; unawareness of symptoms was associated with smaller middle frontal gyrus and symptom misattribution with smaller superior frontal gyrus. In addition, deficit in relabeling symptoms (i.e., misattribution of symptoms) has been correlated with reduced grey matter in posterior cingulate and precuneus in patients during early psychosis (Morgan et al. 2010). Symptom unawareness and misattribution have also been correlated differentially with white matter deficits (Antonius et al. 2012).

With regards to functional imaging, most fMRI studies in schizophrenia have investigated the functional correlates of self-awareness without a separate assessment of insight. The findings from these studies have been inconsistent (Bedford et al. 2012; Murphy et al. 2010, Pauly et al. 2014, Raij et al., 2012), which is not unexpected as each of these studies has employed a different methodology in addition to having differences in study sample, especially in age and duration of psychosis. However, some studies yielded more consistent results (reviewed in details by Shad et al. 2012b) to propose a model of anterior-to-posterior shift in activation of CMS in response to self- versus other-referential stimuli in patients with schizophrenia.

Results from some fMRI studies that have correlated insight behavior with brain activation in response to self-referential activity have, at least partially supported the anterior-to-posterior shift model of CMS activation. For example, Liemberg et al. (2012) showed lower functional connectivity of the ACC within the anterior CMS component and precuneus within the posterior CMS component in patients with poor insight compared to those with good insight using Independent Component Analysis. Another fMRI study using resting state functional connectivity reported impaired insight to be associated with increased connectivity in posterior cingulate cortex with the angular gyrus and in medial prefrontal cortex with insula (Gerretsen et al. 2014). Although Lee et al. (2006) did not aim to study the relationship between insight and self-awareness, they did report a significant relationship between activation of anterior cingulate cortex (one of anterior CMS significantly associated with self-referential activity) and improvement in insight into illness. However, some studies did not report differential activation of anterior and posterior CMS activation in association with insight deficits (Bedford et al. 2012, Raij et al. 2012, van der Meer et al. 2013), which could be explained on the basis of differences in methodology and study sample. For example, the most significant group differences from Bedford et al. (2012) study were based on a contrast between combined self- and other referential and control (letter stimuli) as opposed to most significant findings from our published study were based on a contrast between self- versus other-referential stimuli (Shad et al. 2012a; see online supplement for results).

This study was designed to examine the relationship between brain activation in response to self- versus other-referential stimuli from an fMRI paradigm for self-awareness (see figure 1 in the online supplement) and average scores on a behavioral measure of insight in schizophrenia (i.e., Scale to Assess Unawareness of Mental Disorder [SUMD; Amador et al. 1993]). We predicted that insight deficits will result in anterior-to-posterior shift activation profile in cortical midline structures similar to that observed during self-reflection in patients with schizophrenia in earlier studies (Bedford et al. 2012, Blackwood et al. 2004; Holt et al. 2011a; Raij et al. 2012, Shad et al. 2012a). Since insight is a multidimensional concept and each dimension may have a different neurobiological basis as supported by findings from structural MRI studies (Buchy et al. 2011, Buchy et al. 2012, Morgan et al. 2010, Shad et al. 2006), we also predicted that the core insight dimensions of symptom unawareness and misattribution will be associated with different neurobiological substrates.

Here we are presenting findings from a study in which brain activation in response to self- versus other-directed stimuli in a fMRI paradigm for self-awareness was correlated with average scores on behavioral insight measures of awareness and correct attribution of symptoms to the illness assessed with a comprehensive behavioral measure of insight, Scale to Assess Unawareness of Mental Disorder (SUMD; Amador et al. 1993) in patient volunteers with schizophrenia. The results in activation differences in response to self- vs. other referential stimuli between controls and patient volunteers have been published (Shad et al. 2012a) (see Online Supplement for details of results and methodology.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

The participants in this study included 15 healthy controls and 17 adult volunteers with DSM IV (American Psychiatric Association 1994) based diagnosis of schizophrenia. However, this paper is based on results from patients with schizophrenia. All patients with schizophrenia were right-handed and were being treated with antipsychotic medications. Table 1 shows chlorpromazine-equivalent doses of the antipsychotic medications used in the patient sample along with demographic details which include illness duration and severity, premorbid IQ and education.

Table 1.

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of the Study Subjects

| Age in years (SD) (range) | 40.0 ± 10.3 (22–57) |

| Gender (Males/Females) | 14/3 |

| Mean Education in Years | 13.2±1.9 (9–18) |

| aPremorbid Verbal IQ (range) | 98 ± 11.4 (79–118) |

| Awareness of Symptoms - average | 2.31±1.46 (1–5) |

| Attribution of Symptoms - average | 1.72±1.32 (1–5) |

| PANSS Total (range) | 64.76±14.67 (43–100) |

| PANSS Positive Subscale (range) | 17.1±4.6 (7–26) |

| PANSS Negative Subscale (range) | 15.0±3.7 (10–22) |

| PANSS General Psychopathology Subscale (range) | 32.7±8.0 (24–52) |

| Duration of Illness (years) | 17.88 ± 5.63 |

| Chlorpromazine Equivalent Dose | 346.3± 234.0 |

PANSS, Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale;

Measured with the Wechsler Test for Adult Reading (WTAR; Wechsler, 2001).

2.2. Screening

All volunteers participated in a clinical workup that included administration of the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID; First et al., 1996), completion of a medical history interview, a mental status examination and a physical examination. Subjects with a positive urine test for substance use were excluded from the study. Females currently breast feeding or with a positive urine test for pregnancy were not eligible.

2.3. Study Assessments

The premorbid IQ for schizophrenia volunteers were estimated using the Wechsler Test for Adult Reading (WTAR; Wechsler 2001) and psychopathology was assessed with Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS; Kay et al. 1987).

2.3.1. Insight Assessment

Insight function in patient volunteers was assessed with Scale to Assess Mental Disorder (SUMD; Amador et al. 1993). This scale is a widely used multidimensional instrument to assess insight. It is not hindered by many of the limitations inherent in similar tests (Schwartz, 1998). Primarily, SUMD is a research tool used to evaluate a volunteer's degree of self-awareness related to aspects of their mental disorder. The SUMD demonstrates good construct validity (Markova and Berrios, 1995), inter-rater reliability, and test-retest reliability (Amador and Strauss 1993). The SUMD addresses several dimensions of insight including awareness of having a mental illness, awareness of the need for treatment, awareness of the social consequences of illness, awareness of symptoms and correct attribution of symptoms to the illness. However, for this study we used average scores on awareness of symptoms and correct attribution of symptoms to the illness. These insight dimensions have been used by other studies in the past (Flashman et al. 2001; Buchy et al. 2012; Shad et al. 2006; Shad et al. 2012a) as these insight dimensions provide patients’ awareness into the core psychopathology of the illness and probably an estimate of a higher level of insight function than awareness of illness. The average scores are derived from total score on symptom items (observed in patient volunteers at the time of assessment) divided by number of active symptoms.

Only those symptom items are assessed for attribution of symptoms which the patient volunteers are at least partially aware of (i.e., a score of at least 3 on awareness of symptom items from SUMD). All patients in this study were found to have positive symptoms of schizophrenia, predominantly hallucinations and delusions. However, only three out of 17 patients had negative symptoms. After a structured interview each item is clinician-rated according to a 6-point scale (0=symptom/mental disorder not present, 1=fully aware of symptom/mental disorder, 3=somewhat aware of symptom/mental disorder, 5=unaware of symptom/mental disorder).

2.3.2. Self-Awareness (SA) Task

The details of the SA task are available elsewhere (Shad et al. 2012a). Briefly, this fMRI task was designed to distinguish between one’s own self-evaluation and inferences of self-reference based on the utterances of others (Flavell, 1967). The task was comprised of two cue-question epochs, “Are they talking about you?” (during a self-referential cue epoch [SR]) or “Are they talking about someone else?” (during an other-referential cue epoch [OR]). Each epoch was comprised of blocks of four types of visually presented sentence-stimuli as follows: 1) Self-directed sentence stimulus and 2) Other-directed sentence stimulus. Each study subject was instructed to respond by pressing the right button representing “yes” if he/she think that ‘they’ are talking about him/her or the left button representing ”no” if he/she thinks that ‘they’ are talking about someone else. The structure and examples of the sentence stimuli are described in Shad et al. 2012a. For further details, please refer to figure 1 in the online supplement.

2.4. MRI scans

Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) data were acquired on a Philips 3.0 T Achieva system with a 32 channel receive head coil (Philips Medical Systems, Best, Netherlands). The raw fMRI data acquired from each subject were converted to ANALYZE image format using SPM conversion software (http://sourceforge.net/projects/r2agui/files/r2agui/). 3D-SPGR (resolution=1 mm × 1 mm × 1 mm) and Fluid Attenuation Inversion Recovery (FLAIR) scans were also acquired for each subject. The fMRI pulse sequence used in this study was a gradient echo EPI that is sensitive to the BOLD effect (Ogawa et al. 1990). Images were acquired in the transverse plane using a single shot sequence with SENSE factor = 2.0, with a repetition time = 2000 ms, echo time = 25 ms, flip angle = 80°, number of axial slices = 43, field of view = 220 mm × 220 mm, in-plane resolution = 3.00 mm × 3.00 mm, slice thickness = 3.5 mm without gap, 200 repetitions following six dummy scans, matrix = 64 mm × 64 mm, run duration = 6 min 53 s. The start of each behavioral protocol was automatically triggered by the MRI scanner to coincide with the RF pulse at the start of the first acquired image. Each subject underwent 5 runs, each separated by 1–2 minutes of rest that includes a re-reading of the scripted instructions.

2.5. fMRI processing

Processing of the fMRI data was conducted using Statistical Parametric Mapping (SPM5) software from the Wellcome Department of Cognitive Neurology, London, UK, implemented in the Matlab programming environment (Mathworks Inc. Sherborn MA, USA). Preprocessing included standard SPM5 realignment, coregistration, and normalization, and smoothing. Each fMRI series was realigned to correct head motion, and the five runs were realigned to each other. Any series demonstrating head motion greater than 2.0 mm translation or 2.0° rotation were eliminated from analysis. After coregistering the 3D-SPGR to the fMRI images, the 3D-SPGR was transformed to the coordinates of the Montreal Neurological Institute (MNI) standard space (Collins et al., 1995; Mazziotta et al., 2001) using the automated SPM5 normalization procedure. After normalization, the voxel size of the fMRI images was set to 2 mm isotropic. These images were then spatially smoothed with a Gaussian filter of 8 mm isotropic full width and at half maximum.

A General Linear Model approach was used to specify the design matrix (Friston et al. 1995). High-pass filtering (SPM5 default cut-off of 128 seconds) removed low frequency noise caused by scanner drift. Contrast images of the parameter estimates of interest were computed for each subject during first level of SPM analysis. Then the contrast image for each subject was input into a second level Random Effects comparison. Statistical significance was corrected for multiple comparisons across the voxels within the brain by using the SPM5 Family-Wise Error (FWE)-corrected two-tailed cluster probability value less than 0.05 (Friston et al. 1996). The cluster-defining threshold voxel t was 2.4. Because of two way group comparisons for each cued epoch, the two-tailed probability (P) values were obtained by multiplying by two the corrected one-tailed corrected cluster P-values.

2.6. fMRI statistical analysis

The statistical analysis conducted to examine the relationship between self- vs. other-referential activation and insight measures was based on one of the three separate analyses that were conducted between self-referential (SR) and other referential (OR) cue epoch with self-directed (Self-dir) and other-directed (Other-dir) sentence-stimuli (Shad et al. 2012a; for further details please see the online supplement). The contrast selected to examine correlation between insight measures and self-awareness task induced activations represented the most clear distinction between and SR and OR stimuli (i.e., SRSelf-dir vs. OROther-dir). More specifically, an SPM5 regression analysis was conducted to examine the relationship between activation in response to this contrast and average scores on awareness and misattribution of symptoms. A regression model was also used to control for age, gender, premorbid IQ and illness severity (using total PANSS score). In addition, chlorpromazine-equivalent antipsychotic-dosages were also used as a covariate.

Approximate anatomical labels for regions of activation were determined using Anatomical Automatic Labeling (Tzourio-Mazoyer et al., 2002). The Talairach Daemon (Lancaster et al., 2000) was also used for anatomical labeling of peak coordinates using the Yale Nonlinear MNI to Talairach Conversion Algorithm (Lacadie et al. 2008). For further details please refer to the online supplement.

3. Results

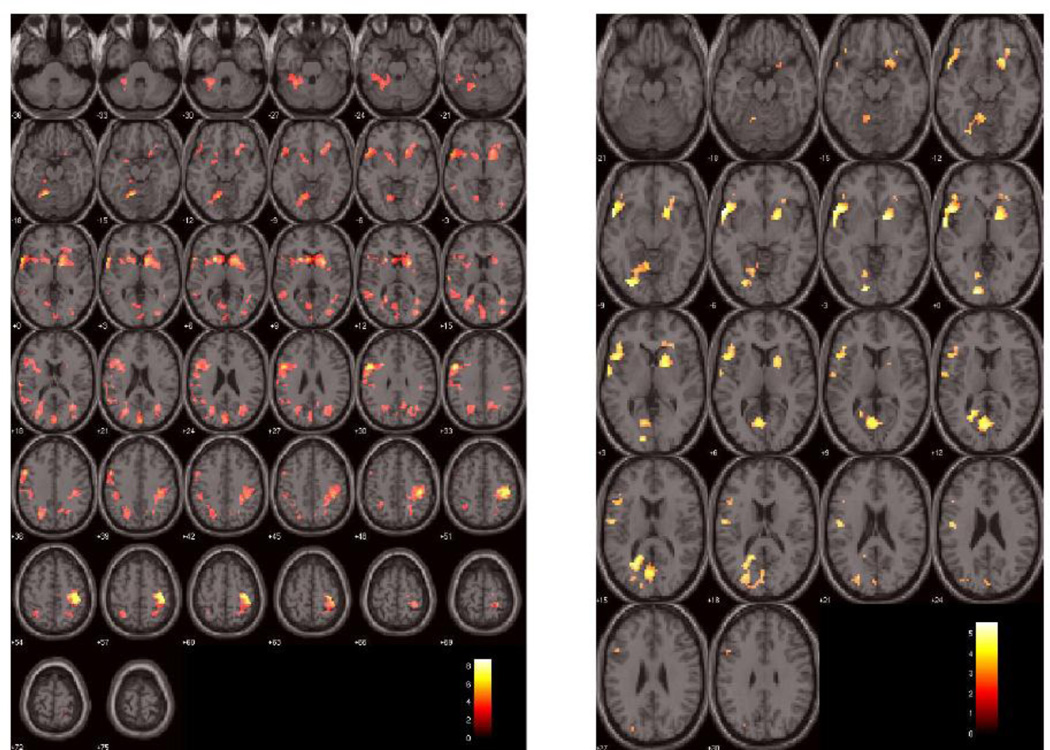

3.1. Behavioral Results

The average score on awareness of symptoms was 2.31±1.46 and attribution of symptoms was 1.72±1.32 (Table 1). The higher score reflect poorer insight. For behavioral responses to the fMRI self-awareness task please refer to table 2 and for imaging results please refer to the result section and figure 2 and table 3 of the online supplement.

Table 2.

Correlation between insight deficits (i.e., unawareness and misattribution of symptoms) and activation in response to self-directed sentence stimuli with the self-referential (SR) metacue (i.e., "are they talking about you?") and other-directed sentence stimuli with the other-referential (OR) metacue (i.e., "are they talking about someone else?"). Within each significant cluster, the relative maximal voxel t value and its approximate anatomical location within 3 mm is listed; [x, y, z] = Montreal Neurological Institute (MNI) standard space coordinates (mm); negative x = left hemisphere. L = left; R = right; g = gyrus; BOLD = blood oxygen level dependent effect; WB = whole brain. Smoothness of residual field (Full Width at Half Maximum “FWHM”) = [11.8 11.9 12.2] mm. Voxel size = [3.0 3.0 3.0] mm. Search volume = 37,404 voxels = 517.9 resolution elements (resels). df = degrees of freedom. g = gyrus; lob = lobules; ant = anterior; post = posterior; inf = inferior; sup = superior; Italics = other brain regions within the cluster

| Correlation | Cluster Label |

Two- tailed FEW- corrected cluster p |

Number of voxels in cluster |

Maximal voxel t value in cluster [15 df] |

MNI coordinates of maximal voxel in cluster (mm) [x, y, z] |

Location of maximal voxel in cluster |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SRSelf-dir vs. OROther-dir and unawareness of symptoms | A | < 0.001 | 1217 | 8.79 | −51, 9, 30 | L frontal inferior operculum Included parts of inf. & middle frontal g, insula, temporal pole, sup temporal g, pallidum, caudate and putamen. |

| B | <0.001 | 881 | 7.35 | 45, −30, 54 | R Precuneus Included parts of middle anterior cingulate g, precuneus, post cingulate, inf & sup parietal lob, supramarginal sulcus, middle temporal g and fusiform g. | |

| C | <0.001 | 491 | 5.93 | −18, −60, −18 | L lingual g Included parts of cerebellum, lingual g, fusiform g, inf temporal and parahippocampal g | |

| D | <0.01 | 251 | 5.48 | −63, −21, 18 | L inferior parietal lobule Included parts of inf. & sup. parietal lob, angular g, sup temporal g. | |

| E | <0.01 | 298 | 4.65 | −24, −60, 15 | Inferior parietal lobule Included parts of inf. & sup. parietal lob and precuneus | |

| SRSelf-dir vs. OROther-dir and misattribution of symptoms | A | <0.01 | 315 | 5.54 | −48, 15, −3 | L frontal inferior triangle Included parts of inf frontal g, sup temporal g and insula |

| B | <0.05 | 206 | 5.19 | 15, 3, −3 | R putamen Included parts of pallidum and caudate | |

| C | <.01 | 406 | 5.14 | −15, −190, 0 | L lingual g Included parts of lingual g, fusiform g, precuenus and cerebellum |

3.2. Correlation between whole-brain BOLD-activation patterns and insight deficits (unawareness and misattribution of symptoms)

3.2A. Correlation between unawareness of symptoms and SRSelf-dir vs. OROther-dir contrast

Five clusters were significant (FWE corrected) for this contrast. Cluster A included portions of frontal lobe (inferior frontal gyrus, middle frontal gyrus, insula), temporal lobe (temporal pole, superior temporal gyrus) and basal ganglia (pallidum, caudate and putamen). Cluster B included portions of frontal lobe (middle anterior cingulate), parietal lobe (precuneus, posterior cingulate, inferior and superior parietal lobules, supramarginal sulcus) and temporal lobe (middle temporal gyrus, fusiform). Cluster C was comprised of the parts of cerebellum and lingual, fusiform, inferior temporal and parahippocampal gyri. Cluster D included parts of inferior parietal lobule, angular gyrus, superior temporal and inferior parietal lobule. Cluster E included portions of inferior and superior parietal lobules and precuneus (Table 2).

3.2B. Correlation between misattribution of symptoms and SRSelf-dir vs. SROther-dir contrast

This contrast produced three significant clusters. Cluster A included inferior frontal and superior temporal gyri and insula. Cluster B included parts of basal ganglia (putamen, pallidum, caudate), orbitofrontal gyrus and insula. Cluster C was formed by the portions of lingual gyrus, cerebellum, fusiform gyrus, occipital cortex and precuenus (Table 2).

3.3. Correlation between whole-brain BOLD-activation patterns and insight deficits (unawareness and misattribution of symptoms) after controlling for age, gender, premorbid IQ, antipsychotic medications and illness severity

Multiple regression for age, gender, IQ, illness severity and chlorpromazine-equivalent doses of antipsychotic medications resulted in activations of similar brain regions as those associated with unawareness of symptoms (during fMRI self-awareness task) except precuneus and superior parietal lobule in clusters B and C after the simple regression. Likewise, misattribution of symptoms was associated with activation of similar brain regions with the exception of basal ganglia during fMRI self-awareness task after simple regression.

4. Discussion

This study revealed association between insight deficits (assessed with SUMD; Amador et al. 1993) and activation of multiple brain regions including cortical midline structures (CMS) such as precuneus and posterior cingulate cortex in response to self- versus other-referential stimuli. In addition, compared to symptom misattribution, symptom unawareness was associated with more robust activations in multiple brain regions including precuneus & posterior cingulate (Table 2). Even the brain regions that shared activations across the two insight dimensions (e.g., inferior frontal gyrus and basal ganglia) revealed differences in magnitude and localization of activations (Table 2). However, several brain regions, such as middle parts of anterior cingulate, posterior cingulate cortex and inferior and superior parietal lobules, were only associated with unawareness and not misattribution of symptoms. This finding is consistent with abnormal activation of superior and middle frontal gyri in association with symptom unawareness in another fMRI study (Bedford et al. 2012). Involvement of inferior frontal region within the DLPFC with both insight dimensions suggests an important role for this specific brain region in processing insight function, especially misattribution of symptoms as it was correlated with both inferior and middle frontal regions of DLPFC. This observation is consistent with the central role of DLPFC in mediating higher-order cognitive function of self-monitoring, which is an integral part of self-referential processing (Hare et al. 2009).

As predicted, unawareness of symptoms was associated with activation of two important posterior CMS; precuneus and posterior cingulate cortex, similar to activation observed in response to self-referential stimuli in patients with schizophrenia (Shad et al. 2012a). However, precuneus activation extended into the middle parts of anterior cingulate cortex in association with symptom unawareness. In contrast, misattribution of symptoms was associated with less robust activation of precuneus as an extension of a large activation blob in lingual cortex. These findings are consistent with relationship between hyperactivation of precuneus and poor insight (Bedford et al. 2012). However, one fMRI study reported activation of both posterior and anterior CMS in response to self-evaluative stimuli. Although this study reported a strong relationship between insight scores and behavioral responses on the fMRI task for self-evaluation, a direct correlation between the two may have been different and more informative (Raij et al. 2012). Further support for involvement of posterior CMS (i.e., precuneus) in self-referential processing comes from altered cerebral blood flow in precuneus (as part of superior parietal lobule) during self- and other-related activity as compared to a control condition (Craik et al. 1999).

Not all studies, however, have reported activation of posterior CMS in association with selfreferential activity and/or poor insight. For example, Faget-Agius et al (2012) reported greater perfusion of precuneus with preserved insight in schizophrenia. However, this study only assessed one dimension of insight from SUMD (i.e., awareness of mental disorder; Amador et al. 1993). In addition, van der Meer (2013) did not find any difference in activation of posterior CMS in response to self-referential stimuli in patients versus controls even using a Region of Interest (ROI)-based analysis. Instead this study reported a correlation between scores on self-reflectiveness item from Beck’s Cognitive Insight Scale (Beck et al. 2004) and activation of ventromedial PFC (an anterior CMS) (van der Meer et al. 2013). Similarly Pauly et al. (2014) did not find any involvement of posterior CMS during self-referential activity, but they did report decreased activation in patients in the anterior medial prefrontal cortex (an anterior CMS) during other- but not self-referential activity.

Activation of a non-CMS structure; inferior parietal lobule (IPL) in association with unawareness of symptoms in this study is not a surprise finding as IPL constitutes a network of specialized neurons known as ‘mirror neurons’ which mediate capacity to interpret the actions and gestures of others (Rizzolatti et al. 2004). Thus along with other parietal regions, IPL may also play a significant role in awareness of symptoms. Prior research has also reported parietal region to be associated with body image and concept of self (Torrey, 2007) and a link has been frequently found between neurological lesions in this brain region and deficits of self-awareness commonly referred to as ‘anosognosia’ (Rosen, 2011). This involvement of IPL is consistent with findings from an earlier study that reported relationship between poor insight and activation of IPL in response to self-evaluative stimuli (van der Meer et al. 2013).

Involvement of posterior CMS as well as parietal cortical regions with symptom unawareness may suggest specific deficits in self-awareness responsible for failure to recognize other’s perspective in order to acknowledge having an illness or its symptoms. Interestingly, Frith 1992 suggested that psychotic symptoms may be an inability to distinguish between external events and perceptual changes caused by patient’s own actions. The basis of this failure could be a functional disconnection between frontal brain areas concerned with action and posterior areas concerned with perception. It is interesting to note that several years later Frith’s hypothesis has been supported by the findings from this study showing an anterior-to-posterior shift in CMS activation in response to self-referential stimuli in association with insight into one’s own symptoms. Furthermore, posterior CMS constitute key regions in the interlinked network of the “default mode” brain areas, which is similar to the neural substrates of the resting conscious state, suggesting that self-monitoring is a core function in resting consciousness (Buckner et al. 2008; Raichle et al. 2007).

The involvement of basal ganglia with symptom unawareness and misattribution is also not unexpected since an increasing number of neuroimaging studies have shown that the basal ganglia are also involved in more integrative and cognitive processes influencing not only the sensory-motor control, but also several different types of cognitive and limbic affective functions (Middleton and Strick, 2000), which underlie complex and integrative processes such as self-awareness, introspective perspective of one’s own self and consciousness (Kircher and Leube, 2003).

Another non-CMS structure associated with symptom unawareness is cerebellum, which has been associated with emotional unawareness (i.e., alexithymia) (Moriguchi et al. 2007) and perception of one’s own actions as opposed to actions of others (Grezes et al. 2004). Berge et al. (2012) found a significant correlation between insight deficits and grey matter reduction in cerebellum. Last but not the least, temporal cortex also revealed the most widespread clusters activation associated with symptom unawareness. This is an interesting finding as parts of this brain region mediates psychotic symptoms, especially auditory hallucinations and may reflect sensory overload resulting in attribution of abnormal salience to sensory stimuli.

The association of multiple cluster activations associated with symptom unawareness suggests that these insight deficits may be a reflection of changes in several neural circuits and underscores the highly complex nature of this phenomenon. For example, activation of each of brain region associated with symptom unawareness may represent a specific brain dysfunction or disconnect between these regions contributing towards the insight deficit. Thus, temporolimbic activation may suggest a sensory overload (Freedman et al. 1987) overwhelming the frontal brain regions and resulting in abnormal activation of several frontal regions thus compromising the ability to self-monitor (Hare et al. 2009) and attributing aberrant salience to the sensory stimuli (Kapur, 2003). In addition, widespread activations could be an effort to compensate for deficits in processing self-relevant information. Furthermore, multiple brain activations could be a reflection of neurological heterogeneity of psychotic symptoms (Arango et al. 2000).

In contrast to multiple activations (including activation of posterior cingulate and precuneus regions of posterior CMS) observed with symptom unawareness, fewer clusters of brain activations were associated with symptom misattribution (Table 2). These brain clusters were primarily limited to specific parts of frontal, temporal and striatal areas. Since correct attribution of symptoms to an illness requires some level of symptom awareness, it represents a higher level of insight function (i.e., intellectual insight) than required to recognize having an illness. The fewer and smaller clusters of brain activations associated with symptom misattribution may suggest a failure to recruit compensatory brain mechanisms. It is interesting that unawareness of symptoms was associated with more widespread deficits in white matter than misattribution of symptoms (Antonius et al. 2012). These white matter changes were reported in some of the same brain regions that were differentially associated with unawareness and misattribution of symptoms in this study. These results support the notion that symptom unawareness may be a function of a more complex brain network and symptom misattribution may be mediated by specific brain regions.

However, the results from this study are based on a small sample of patients with chronic schizophrenia using an fMRI task for self-awareness as a surrogate for insight function and thus should be interpreted with caution. In addition, despite observing no effects of illness duration and antipsychotic treatment on the study results, the influence of these confounders on brain changes cannot be completely ruled out. Bearing these limitations in mind, the present study provides initial support for interesting neurobiological similarities between self-referential processing and insight function along with differences in brain regions associated with unawareness and misattribution of symptoms in patients with schizophrenia. However, it is important to mention that despite these neurobiological similarities there were noticeable differences between neural substrates for self-awareness and those associated with insight deficits. A direct measure of insight under the scanner may be able to more clearly delineate specific differences in neurobiology of various insight deficits. Furthermore, all patients in this study had positive symptoms (i.e., primarily hallucinations and delusions) with only a few with negative symptoms, making it difficult to analyze differences in neurobiological underpinnings of insight into positive versus negative symptoms of schizophrenia.

Thus, future research in this highly complex area of brain function will require development of an fMRI task to directly assess insight function under the scanner in order to enhance our understanding of the neurobiology of insight in schizophrenia. In addition, it will be interesting to formally compare between the neurobiology of insight into positive and negative symptoms as they may have different neural substrates.

Supplementary Material

Figure 1.

Brain regions associated with behavioral measures of insight. Left figure shows brain regions associated with unawareness of symptoms and right figure shows brain regions associated with misattribution of symptoms in response to the self-directed stimuli in the self-referential condition vs. other-directed stimuli in the other-referential condition. The activations are overlayed in color on axial slices of the MNI single-subject template brain. The number below each slice indicates slice location (mm) of MNI z coordinate. Scale on color bar represents t values.

Acknowledgments

The author is thankful to Dr. Carol Tamminga, Dr. Joel Steinberg and Dr. Binu Thomas for their expertise in analyzing and/or interpreting fMRI data for this study.

Role of the funding resource:

This study was entirely funded through a K23-Mentored Research Grant (K23 MH 077924-05) and also provided 75% salary support to enable the research and training aspects associated with this study.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Author Disclosure

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Contributors:

Dr. Keshavan was initially my mentor and later became one of the main external consultants for this study. He provided his expertise in reviewing and analyzing the fMRI and insight data for this study. He also reviewed and edited the submitted manuscript.

References

Other studies have also identified anterior cingulate as one of the core prefrontal brain regions showing reduced activation in response to self-relevant activity in volunteers with denial of loss of motor function (i.e., anosognosia), traumatic brain injury and frontotemporal and Alzheimer’s dementia (Mendez & Shapira, 2005; Schmitz et al., 2006).

- Amador XF, Strauss DH. Poor insight in schizophrenia. Psychiatr Q. 1993;64:305–318. doi: 10.1007/BF01064924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amador XF, Flaum M, Andreasen NC, Strauss DH, Yale SA, Clark SC. Awareness of illness in schizophrenia, schizoaffective and mood disorders. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1994;51:826–836. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1994.03950100074007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. Fourth Edition. Washington D.C.: APA; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Antonius D, Prudent V, Rebani Y, D'Angelo D, Ardekani BA, Malaspina D, Hoptman MJ. White matter integrity and lack of insight in schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder. Schizophr Res. 2011;128(1–3):76–82. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2011.02.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arango C, Kirkpatrick B, Buchanan RW. Neurological Signs and the Heterogeneity of Schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157:560–565. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.4.560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Baruch E, Balter JM, Steer RA, Warman DM. A new instrument for measuring insight: the Beck Cognitive Insight Scale. Schizophr Res. 2004;68(2–3):319–329. doi: 10.1016/S0920-9964(03)00189-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergé D, Carmona S, Rovira M, Bulbena A, Salgado P, Vilarroya O. Gray matter volume deficits and correlation with insight and negative symptoms in first-psychotic-episode subjects. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2011;123(6):431–439. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2010.01635.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackwood NJ, Bentall MFMF, Ffytche MF, Simmons A, Murray RM, Howard RJ. Persecutory delusions and the determination of self-relevance: an fMRI investigation. Psychol Med. 2004;34(4):591–596. doi: 10.1017/S0033291703008997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckner RL, Andrews-Hanna JR, Schacter DL. The Brain's Default Network: Anatomy, Function, and Relevance to Disease. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2008;1124(1):1–38. doi: 10.1196/annals.1440.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchy L, Ad-Dab'bagh Y, Malla A, Lepage C, Bodnar M, Joober R, Sergerie K, Evans A, Lepage M. Cortical thickness is associated with poor insight in first-episode psychosis. J Psychiatr Res. 2011;45(6):781–787. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2010.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchy L, Ad-Dab'bagh Y, Lepage C, Malla A, Joober R, Evans A, Lepage M. Symptom attribution in first episode psychosis: a cortical thickness study. Psychiatry Res. 2012;203(1):6–13. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2011.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooke MA, Fannon D, Kuipers E, Peters E, Williams SC, Kumari V. Neurological basis of poor insight in psychosis: a voxel-based MRI study. Schizophr Res. 2001;103(1–3):40–51. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2008.04.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins L, Holmes C, Peters T, Evans A. Automatic 3-D model-based neuroanatomical segmentation. Hum Br Mapping. 1995;3:190–208. [Google Scholar]

- Craik FI, Moroz TM, Moscovitch M, Stuss DT, Winocur G, Tulving E, Kapur S. In Search of the Self: A Positron Emission Tomography Study. Psychological Science. 1999;10:26. [Google Scholar]

- David A, Buchanan A, Reed A, Almeida O. The assessment of insight in psychosis. British Journal of Psychiatry. 1992;161:599–602. doi: 10.1192/bjp.161.5.599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Debowska G, Grzywa A, Kucharska-Pietura K. Insight in paranoid schizophrenia—its relationship to psychopathology and premorbid adjustment. Comprehensive Psychiatry. 1998;39(5):255–260. doi: 10.1016/s0010-440x(98)90032-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickerson FB, Boronow JJ, Ringel N, Parente F. Lack of insight among outpatients with schizophrenia. Psychiatric Services. 1997;48:195–199. doi: 10.1176/ps.48.2.195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faget-Agius C, Boyer L, Padovani R, Richieri R, Mundler O, Lançon C, Guedj E. Schizophrenia with preserved insight is associated with increased perfusion of the precuneus. J Psychiatry Neurosci. 2012;37(5):297–304. doi: 10.1503/jpn.110125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JB. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders Patient Edition. New York: Biometrics Research Department, New York State Psychiatric Institute; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Flashman LA, McAllister TW, Johnson SC, Rick JH, Green RL, Saykin AJ. Specific frontal lobe subregions correlated with unawareness of illness in schizophrenia: a preliminary study. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2001;13(2):255–257. doi: 10.1176/jnp.13.2.255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flavell JH. Metacognitive aspects of problem solving. In: Resnick LB, editor. The nature of intelligence. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1976. pp. 231–236. [Google Scholar]

- Freedman R, Adler LE, Gerhardt GA, Waldo M, Baker N, Rose GM, Drebing C, Nagamoto H, Bickford-Wimer P, Franks R. Neurobiological Studies of Sensory Gating in Schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 1987;13(4):669–678. doi: 10.1093/schbul/13.4.669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friston KJ, Holmes A, Worsley KJ, Poline JP, Frith CD, Frackowiak RSJ. Statistical parametric maps in functional imaging: a general linear approach. Hum Br Mapping. 1995;2:189–210. [Google Scholar]

- Friston KJ, Holmes A, Poline JB, Price CJ, Frith CD. Detecting activations in PET and fMRI: levels of inference and power. Neuroimage. 1996;4:223–235. doi: 10.1006/nimg.1996.0074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frith CD. The Cognitive Neuropsychology of Schizophrenia. Hove: Lawrence Erlbaum; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Grèzes J, Frith CD, Passingham RE. Inferring false beliefs from the actions of oneself and others: an fMRI study. Neuroimage. 2004;21(2):744–750. doi: 10.1016/S1053-8119(03)00665-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerretsen P, Menon M, Mamo DC, Fervaha G, Remington G, Pollock BG, Graff-Guerrero A. Impaired insight into illness and cognitive insight in schizophrenia spectrum disorders: resting state functional connectivity. Schizophr Res. 2014;160(1–3):43–50. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2014.10.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hare TA, Camerer CF, Rangel A. Functional interactions between inferotemporal and prefrontal cortex in a cognitive task. Brain Research. 2009;330(2):299–307. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(85)90689-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haro MJ, Ochoa S, Cabrero L. Insight and use of health resources in patients with schizophrenia. Actas Españolas de Psiquiatría. 2001;29(2):103–108. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holt DJ, Cassidy BS, Andrews-Hanna JR, Lee SM, Coombs G, Goff DC, Gabrieli JD, Moran JM. An anterior-to-posterior shift in midline cortical activity in schizophrenia during self-reflection. Biol Psychiatry. 2011;69(5):415–423. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapur S. Psychosis as a State of Aberrant Salience: A Framework Linking Biology, Phenomenology, and Pharmacology in Schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160:13–23. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.1.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kay SR, Fishbein A, Opier LA. The Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) for schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 1987;13(2):261–276. doi: 10.1093/schbul/13.2.261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly BD, Clarke M, Browne S, McTigue O, Kamali M, Gervin M, Kinsella A, Lane A, Larkin C, O’Callaghan E. Clinical predictors of admission status in first episode schizophrenia. European Psychiatry. 2004;19(2):67–71. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2003.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kircher TTJ, Leube DT. Self-consciousness, self-agency, and schizophrenia. Consciousness and Cognition. 2003;12(4):656–669. doi: 10.1016/s1053-8100(03)00071-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacadie CM, Fulbright RK, Rajeevan N, Constable RTX, Papademetris X. More accurate Talairach coordinates for neuroimaging using non-linear registration. Neuroimage. 2008;42:717–725. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.04.240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lancaster JL, Woldorff MG, Parsons LM, Liotti M, Freitas CS, Rainey L, Kochunov PV, Nickerson D, Mikiten SA, Fox PT. Automated Talairach atlas labels for functional brain mapping. Hum Br Mapping. 2000;10:120–131. doi: 10.1002/1097-0193(200007)10:3<120::AID-HBM30>3.0.CO;2-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee KH, Brown WH, Egleston PN, Green RD, Farrow TF, Hunter MD, Parks RW, Wilkinson ID, Spence SA, Woodruff PW. A functional magnetic resonance imaging study of social cognition in schizophrenia during an acute episode and after recovery. Am. J. Psychiatry. 2006;163:1926–1933. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2006.163.11.1926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liemburg EJ, van der Meer L, Swart M, Curcic-Blake B, Bruggeman R, Knegtering H, Aleman A. Reduced connectivity in the self-processing network of schizophrenia patients with poor insight. PLoS One. 2012;7(8):e42707. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0042707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markova IS, Berrios GE. Insight in clinical psychiatry: A new model. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1995;183:743–751. doi: 10.1097/00005053-199512000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazziotta J, Toga A, Evans A, Fox P, Lancaster J, Zilles K, Woods R, Paus T, Simpson G, Pike B, Holmes C, Collins L, Thompson P, MacDonald D, Iacoboni M, Schormann T, Amunts K, Palomero-Gallagher N, Geyer S, Parsons L, Narr K, Kabani N, Le Goualher G, Boomsma D, Cannon T, Kawashima R, Mazoyer B. A probabilistic atlas and reference system for the human brain: International Consortium for Brain Mapping (ICBM) Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society London B: Biol Sci. 2001;356:1293–1322. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2001.0915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEvoy JP, Apperson J, Appelbaum PS, Ortilip P, Brecosky J, Hammill K, Geller JL, Roth L. Insight in schizophrenia: its relationship to acute psychopathology. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 1989;177:3–47. doi: 10.1097/00005053-198901000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Middleton FA, Strick PL. Basal ganglia and cerebellar loops: motor and cognitive circuits. Brain Research Reviews. 2000;31(2–3):236–250. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(99)00040-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan KD, Dazzan P, Morgan C, Lappin J, Hutchinson G, Suckling J, Fearon P, Jones PB, Leff J, Murray RM, David AS. Insight, grey matter and cognitive function in first-onset psychosis. Br J Psychiatry. 2010;197(2):141–148. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.109.070888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moriguchi Y, Ohnishi T, Mori T, Matsuda H, Komaki G. Changes of brain activity in the neural substrates for theory of mind during childhood and adolescence. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2007;61(4):355–363. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1819.2007.01687.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy ER, Brent BK, Benton M, Pruitt P, Diwadkar V, Rajarethinam RP, Keshavan MS. Differential processing of metacognitive evaluation and the neural circuitry of the self and others in schizophrenia: a pilot study. Schizophr Res. 2010;116(2–3):252–258. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2009.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogawa S, Lee TM, Kay AR, Tank DW. Brain magnetic resonance imaging with contrast dependent on blood oxygenation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1990;87:9868–9872. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.24.9868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pauly KD, Kircher TT, Schneider F, Habel U. Me, myself and I: temporal dysfunctions during self-evaluation in patients with schizophrenia. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci. 2014;9(11):1779–1788. doi: 10.1093/scan/nst174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perkins DO. Predictors of noncompliance in patients with schizophrenia. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2002;63(12):1121–1128. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v63n1206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raichle Marcus E, Snyder Abraham Z. A default mode of brain function: A brief history of an evolving idea. NeuroImage. 2007;37(4):1083–1090. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.02.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raij TT, Riekki TJ, Hari R. Association of poor insight in schizophrenia with structure and function of cortical midline structures and frontopolar cortex. Schizophr Res. 2012;139(1–3):27–32. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2012.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rizzolatti G, Craighero L. The mirror-neuron system. Annual Rev Neurosci. 2004;27:169–192. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.27.070203.144230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosen K, Garety P. Predicting recovery from schizophrenia: a retrospective comparison of characteristics at onset of people with single and multiple episodes. Schizophr Bull. 2005;31:735–750. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbi017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosen HJ. Anosognosia in neurodegenerative disease. Neurocase. 2011;17(3):231–241. doi: 10.1080/13554794.2010.522588. Review. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sartorius N, Shapiro R, Kimura M, Barrett K. WHO International Pilot Study of Schizophrenia. Psychological Medicine. 1972;2(4):422–425. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700045244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz RC. Insight and Illness in Chronic Schizophrenia. Comprehensive Psychiatry. 1998;39(5):249–254. doi: 10.1016/s0010-440x(98)90031-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz RC, Cohen BN, Grubaugh A. Does insight affect long-term impatient treatment outcome in chronic schizophrenia? Comprehensive Psychiatry. 1997;38(5):283–288. doi: 10.1016/s0010-440x(97)90061-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shad MU, Brent BK, Keshavan M. Neurobiology of Self-Awareness in Schizophrenia: A hypothetical Model. Asian J Psychiatry. 2012b;4(4):248–254. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2011.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shad MU, Keshavan M, Steinberg JL, Mihalakos P, Thomas B, Motes M, Soares JC, Tamminga CA. Neurobiology of Self-Awareness in Schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2012a;138:113–119. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2012.03.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shad MU, Mudassani S, Keshavan MS. Insight and prefrontal sub-regions in first-episode schizophrenia—a pilot study. Psychiatry Research. Neuroimaging. 2006;146:35–42. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2005.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shad MU, Muddasani S, Sahni SD, Keshavan MS. Insight and prefrontal cortex in firstepisode schizophrenia. NeuroImage. 2004;22(3):1315–1320. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torrey EF. Schizophrenia and the inferior parietal lobule. Schizophr Res. 2007;97(1–3):215–225. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2007.08.023. Review. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tzourio-Mazoyer N, Landeau B, Papathanassiou D, Crivello F, Etard O, Delcroix N, Mazoyer B, Joliot M. Automated anatomical labelling of activations in spm using a macroscopic anatomical parcellation of the MNI MRI single subject brain. Neuroimage. 2002;15:273–289. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2001.0978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Meer L, de Vos AE, Stiekema AP, Pijnenborg GH, van Tol MJ, Nolen WA, David AS, Aleman A. Insight in schizophrenia: involvement of self-reflection networks? Schizophr Bull. 2013;39(6):1288–1295. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbs122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler D. Wechsler test of adult reading. San Antonio, Texas: The Psychological Corporation; 2001. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.