Abstract

The last two decades of neurosurgery have seen flourishing use of the endonasal approach for the treatment of skull base tumors. Safe and effective resections of neoplasms requiring intracranial arterial dissection have been performed using this technique. Recently, there have been a growing number of case reports describing the use of the endonasal approach to surgically clip cerebral aneurysms. We review the use of these approaches in intracranial aneurysm clipping and analyze its advantages, limitations, and consider future directions. Three major electronic databases were queried using relevant search terms. Pertinent case studies of unruptured and ruptured aneurysms were considered. Data from included studies were analyzed. 8 case studies describing 9 aneurysms (4 ruptured and 5 unruptured) treated by the endonasal approach met inclusion criteria. All studies note the ability to gain proximal and distal control and successful aneurysm obliteration was obtained for 8 of 9 aneurysms. 1 intraoperative rupture occurred and was controlled, and delayed complications of cerebrospinal fluid leak, vasospasm, and hydrocephalus occurred in 1, 1, and 2 patients, respectively. Described limitations of this technique include aneurysm orientation and location, the need for lower profile technology, and challenges with handling intraoperative rupture. The endonasal approach for clipping of intracranial aneurysms can be an effective approach in only very select cases as demonstrated clinically and through cadaveric exploration. Further investigation with lower profile clip technology and additional studies need to be performed. Options of alternative therapy, limitations of this approach, and team experience must first be considered.

Keywords: endoscopic, endonasal, cerebral aneurysm, clipping

Introduction

The field of endonasal surgery has been revolutionized in the past two decades through advances in endoscopic and microscopic optics, neuroimaging, neuronavigation, and surgical instrumentation. Endonasal approaches (EA) provide a direct corridor to intracranial and extracranial anterior cranial base pathology facilitating removal of tumors and repair of cranial base defects with minimal morbidity[1]. At times, they can be expanded to reach for pathology extending to the adjacent middle and posterior cranial fossa[2]. Furthermore, successful intracranial arterial dissection and neurovascular manipulation has been performed for complex tumor resection through this approach.

This growing success and the continuous evolution of aneurysm treatment has prompted some neurosurgeons to utilize the EA to surgically clip intracranial saccular aneurysms. This is an exciting, novel, and provocative advancement in the field of cerebrovascular and skull base neurosurgery. Increasing numbers of case reports and cadaveric studies have recently been published. The purpose of this manuscript is to critically assess the existing literature on endonasal techniques utilized to clip intracranial aneurysms and analyze the described advantages and limitations of this novel approach. This will help identify when the EA can complement or possibly supplant existing cranial and endovascular techniques for the treatment of intracranial aneurysms.

Methods

We conducted a systematic review of the literature pertaining to endonasal clipping of intracranial aneurysms. Three independent reviewers (D.M.H., A.S., and A.V.G.) performed detailed electronic searches of major electronic databases including MEDLINE (PubMed and Ovid), Cochrane Library, and Google scholar for studies published between January 1970 and December 2014 written on this topic without language restriction. Searched keywords and MeSH terms were: “endoscopic”, “microscopic”, “endoscopic-assisted”, “endonasal”, “sublabial”, “transnasal”, and “intracranial aneurysm”. Relevant case studies of unruptured and ruptured aneurysms were considered, including those performed in conjunction with craniotomy, through sublabial exposure, and on occluded aneurysms. References of these studies, all “related articles,” and all “cited by” articles were manually screened to include any additional applicable studies. Data from included studies were summarized qualitatively, addressing patient demographics, aneurysm size, morphology, location, and orientation, visualization tool, ability to gain vascular control, clip construct, postoperative course, complications, and long-term follow-up.

Results

Eight case studies describing nine aneurysms (four ruptured and five unruptured) treated by an EA met inclusion criteria (Tables 1-3). Four studies describe a purely endoscopic endonasal approach (EEA) for aneurysm clipping, two studies report an endoscopic or endoscopic-assisted sublabial EA, one study describes an EEA for aneurysmorrhaphy, and one study notes an EEA following craniotomy in the same operative setting. Anterior and posterior circulation aneurysms were treated, and titanium aneurysm clips were used in treating eight of nine aneurysms. One aneurysm was treated using a low-profile Weck clip (Weck Closure Systems, Research Triangle Park, NC) because of difficulty with dural closure from the higher profile hub of a titanium aneurysm clip[3]. All studies note the ability to gain proximal and distal control and successful aneurysm obliteration was obtained in eight of nine aneurysms. Postoperative angiography on a patient with a ruptured basilar trunk aneurysm that underwent an EA for clipping revealed continued dilation in the region of the aneurysm and the patient underwent endovascular stent placement with subsequent reduction in size of her aneurysm on delayed 3-month angiography[3]. A postoperative CT angiogram on another patient revealed partial filling of a basilar aneurysm and AVM vessel and underwent repeat EEA the next day with complete obliteration of the aneurysm and AVM[4]. One intraoperative rupture occurred and was controlled without any complications[5]. Delayed complications of CSF leak, vasospasm, and hydrocephalus each occurred in one, one, and two patients, respectively, all of whom had posterior circulation aneurysms[3, 6]. CSF rhinorrhea presented 15 days postoperatively in a patient with a ruptured vertebral-PICA aneurysm treated with the EA and was treated with repeat endonasal exploration and repair of necrotic nasoseptal flap; this patient ultimately developed hydrocephalus treated with ventriculoperitoneal shunting[6]. The patient with a ruptured basilar trunk aneurysm developed vasospasm treated with hypertensive therapy and hydrocephalus treated with lumboperitoneal shunting[3]. There were no reports of infection.

Table 1.

Demographics/Aneurysm Characteristics

| Report | Patient Age/Sex | Aneurysm Location | Size (mm) | Ruptured (Y/N) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kassam 2006 | 51/F | R. VA | 11 | Unruptured |

| Kassam 2007 | 56/F | L. SHA | 5 | Unruptured |

| Kitano 2007 | 58/F | ACoA | “small” | Unruptured |

| Eloy 2008 | 28/F | BA trunk | 2.5 | HH3, FG3 |

| Germanwala 2011 | 42/F | R. Paraclinoidal ICA | 10 | HH2, FG1 |

| R. OA | 5 | |||

| Ensenat 2011 | 74/F | R. VA-PICA | 1.2 | HH3, FG2 |

| Froelich 2011 | 55/M | ACoA | 7 | Unruptured |

| Drazin 2012 | 59/F | R. BA- SCA | 4 | HH2 |

Table 3.

Reconstruction Technique and Complications

| Report | Reconstruction Technique | Lumbar Drain (Y/N) | Complications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kassam 2006 | Inlay and onlay avascular grafts | Y | Dislodged nasal packing requiring repair, Pneumonia and PE |

| Kassam 2007 | Inlay avascular and onlay vascularized grafts | N | Confusion, small callosal infarct likely due to perforator occlusion during ACoA clipping |

| Kitano 2007 | Inlay avascular graft, sutured avascular graft, extradural cement | N | None |

| Eloy 2008 | Sutured avascular graft, extradural fat/cartilage | Y | Vasospasm, Hydrocephalus requiring lumboperitoneal shunting |

| Germanwala 2011 | Inlay avascular and onlay vascularized grafts | Y | None |

| Ensenat2011 | Inlay and onlay avascular and onlay vascularized grafts | Y | CSF leak 2 weeks post-op, necrotic NSF, Hydrocephalus requiring ventriculoperitoneal shunting |

| Froelich 2011 | Inlay avascular and onlay vascularized grafts | Y | None |

| Drazin 2012 | Inlay and onlay avascular and onlay vascularized grafts | Y | Incomplete aneurysm occlusion and persistent AVM filling; Persistent epistaxis |

1. Early EA Aneurysm Clippings (2006-2008)

Kassam and colleagues pioneered the use of the EEA to successfully clip intracranial aneurysms[7, 8]. In 2006, they described a 51-year-old woman with an unruptured 11-mm vertebral artery (VA) aneurysm who initially presented with severe headaches, neck pain, hemisensory changes, left leg weakness, incoordination, and vertigo[7]. The initial treatment plan to treat the aneurysm was endovascular trapping with coils; however, mass effect from the successfully thrombosed aneurysm remained, leaving the patient with persistent long-tract deficits. At this juncture the authors elected to use the EEA for aneurysmorrhaphy due to several factors including: aneurysm location, avoidance of symptom progression, the fact the aneurysm was secured from endovascular therapy, and the extensive experience the surgical team had using this particular approach. The surgery was successful without any intraoperative complications via a transclival approach combined with removal of the medial occipital condyle and medial C1 superior articular facet. On postoperative day 1, the patient dislodged and deflated the balloon used for skull base reconstruction. This compromised the repair, and the patient was returned to the operating room for graft reconstruction to help prevent the risk of CSF leak or infection. At 6 weeks post-operatively, the patient showed improvement of preoperative deficits arising from the mass effect caused by the thrombosed aneurysm. The same group published a case report one year later of successfully clipping an unsecured, unruptured 5-mm left superior hypophyseal artery (SHA) aneurysm through the EEA in a 56-year-old patient that was discovered incidentally[8]. This patient also had an unruptured anterior communicating artery (ACoA) aneurysm for which she first underwent a craniotomy without dural opening in the same operative setting. The EEA was favored for the SHA aneurysm because of its orientation and the risk of optic apparatus injury with traditional craniotomy approaches. The EEA was utilized for clipping of the SHA aneurysm followed by transcranial ACoA aneurysm clipping. An EEA approach for the ACoA aneurysm was not performed because of unfavorable anatomical location that would require excessive optic nerve manipulation. The CT scan post-operatively confirmed clip placement and a small callosal infarct attributed to perforator injury during clipping of the ACoA aneurysm.

Kitano et al. reported a case in 2007 of a small ACoA aneurysm that was incidentally discovered and clipped during an endoscopic sublabial approach for a non-functioning macroadenoma in a 58 year-old woman[9]. The patient presented with a non-functioning pituitary adenoma that was initially resected transphenoidally using a sublabial approach. Due to persistent symptoms and residual growth on follow-up imaging, the authors elected to perform another surgery, and during the tumor resection via repeat sublabial approach, the aneurysm was incidentally discovered. The surgical corridor created initially during the tumor resection gave the authors access to successfully clip the aneurysm safely using the endoscope via a sublabial approach. Her postoperative course was uneventful and the patient was discharged without any neurological deficits

Eloy et al. reported a sublabial microscopic approach with endoscopic assistance in 2008 for a 2.5-mm ruptured mid-basilar trunk aneurysm[3]. Initial endovascular treatment was deemed suboptimal given the small size of the aneurysm and the possible need for antiplatelet therapy. The patient underwent a sublabial approach and exploration revealed a large thrombosed basilar artery aneurysm dome. The neck of the aneurysm was initially clipped with a standard curved aneurysm clip, but the profile was too large to allow for dural reconstruction. The clip was then replaced with a Weck clip. Postoperative angiography showed persistent fusiform dilatation “in the region of the aneurysm,” and the patient underwent basilar artery stent placement and antiplatelet therapy. The patient did develop vasospasm and hydrocephalus that was treated with a lumboperitoneal shunt. Delayed angiography revealed decrease in size of the fusiform basilar artery and the patient remained at her neurological baseline at 14-months post-procedure.

2. Later EEA Aneurysm Clippings (2011-2012)

Germanwala et al. described the clipping of multiple intracranial aneurysms using the EEA in 2011[5]. They reported a 42 year-old woman who initially presented with a subarachnoid hemorrhage. An arteriogram revealed a 10-mm right paraclinoidal (ruptured) aneurysm and a 5-mm right ophthalmic artery wide-necked (unruptured) aneurysm. The authors in this report demonstrated that this approach was feasible and effective for clipping both aneurysms and obtaining proximal and distal control. At one-year follow-up, the patient remained neurologically intact and imaging showed patency of the surrounding vasculature with no aneurysm recurrence. Aneurysm location plays a crucial role in determining whether this surgical approach may be feasible or favored over a traditional approach. In this particular case, the extensive anterior clinoid drilling and manipulation of the optic nerve that would have been required via a craniotomy, aneurysm morphology and orientation, age of the patient, and their experience influenced the authors’ use of the EEA.

In 2011, Ensenat et al. reported clipping a 1.2-mm ruptured right VA aneurysm in close proximity of the right posterior inferior cerebellar artery via the EEA in a 74-year-old patient who initially presented with a SAH[6]. The authors excluded the option of endovascular treatment of stent-assisted coiling due the high risk of posterior inferior cerebellar artery (PICA) occlusion due to the aneurysm location. Due to the location, orientation and size of this particular aneurysm, the endoscopic approach provided a direct surgical route to safely clip the aneurysm. The patient was neurologically intact after the operation, but suffered a CSF leak on postoperative day 15. An endonasal exploration at this time revealed necrosis of the vascularized flap pedicle used for skull base reconstruction; this was subsequently replaced with a new vascularized inferior turbinate flap. This patient went on to develop hydrocephalus that was ultimately treated with a ventriculoperitoneal shunt.

In 2011, Froelich et al. reported the successful endoscopic endonasal clipping of a 7-mm unruptured ACoA aneurysm in a 55 year-old male[10]. The patient initially presented with progressive decreased visual acuity on the right side and imaging revealed an orbital lesion in the medial aspect of orbital apex and optic canal. The ACoA aneurysm was incidentally discovered on imaging prior to the endoscopic biopsy for the orbital lesion. The authors elected to clip the aneurysm endoscopically in a separate procedure due to the favorable surgical corridor created during the endoscopic biopsy, orientation of the aneurysm, experience of the surgeons using the endoscopic endonasal approach, and absence of perforators on the back of the aneurysm neck. The post-operative course was uneventful and a 1-month follow-up angiogram revealed complete exclusion of the aneurysm.

Drazin et al. reported in 2012 the clipping of a 4-mm ruptured basilar trunk aneurysm and its associated AVM feeding vessel in the cerebellum of a 59 year-old woman who initially presented with a subarachnoid hemorrhage[4]. The authors decided to use the EEA in this particular case after multiple unsuccessful attempts to obliterate the aneurysm and its feeding vessel via endovascular and open craniotomy techniques. A postoperative angiogram revealed partial occlusion of the aneurysm and persistent filling of the AVM, and the patient was taken back to the operating room the next day where a second clip was placed at the dome of the aneurysm via a repeat EEA, resulting in immediate occlusion. The patient made a full neurological recovery.

Discussion

The treatment of cerebral aneurysms continues to evolve. Saccular aneurysms are treated with traditional cranial approaches for extra-luminal clipping that obliterates the aneurysm and reconstructs the vessel wall or by newer intraluminal techniques that obliterate the aneurysm by filling the sac or excluding it with flow-diverting stents. Each approach has distinct advantages and limitations.

Traditional open craniotomy approaches, often supplemented with removal of the zygoma and/or orbital bone, provide unrivaled exposure to the cerebral vasculature. The latitude afforded through this approach and the stereoscopic vantage given by the operating microscope allows proximal and distal vascular control, precise visualization of the aneurysm and neck from multiple angles, individualization of the clip construct, drainage of CSF cisterns for brain relaxation, and the ability to zoom-in on the aneurysm and its associated vessels, maximizing the safety and efficacy of the clipping procedure. The use of the endoscope as an adjunct to the microscope to clip intracranial aneurysms via craniotomy has been well described in the literature[11, 12]. Reported advantages include better visualization of cerebrovascular branch points[13].

However, comparative literature showing more favorable outcomes and lower periprocedural morbidity with endovascular embolization has led to a paradigm shift towards these minimally invasive endovascular options[14-16]. In fact, the majority of ruptured and unruptured aneurysms have now been treated endovascularly since 2008[17]. Advancements in neurovascular technology, the facility of the endovascular approach, the immediacy of assessing aneurysmal obliteration and surrounding vasculature preservation, and the ability to treat vasospasm, have led to the burgeoning of this subspecialty.

Nevertheless, recent long-term studies have shown lower rates of recurrence and retreatment with surgical clipping[18]. Furthermore, certain aneurysms are suboptimal for endovascular treatment because of small size, distal location, neck to dome ratio, and the treating physician's reluctance to start antiplatelet therapy in the setting of acute hemorrhage and stent placement[19]. Most centers, therefore, have multidisciplinary reviews to offer surgical and interventional opinions and treat patients on an individual basis.

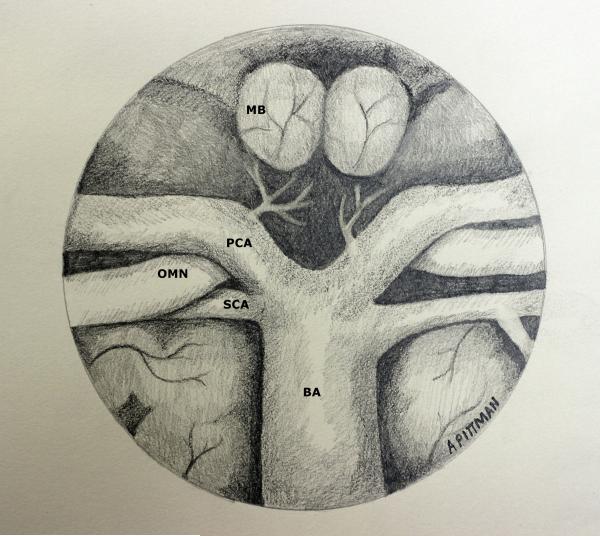

The EA for intracranial aneurysm treatment has described advantages that make it, at best, an option in limited cases by very experienced teams if surgical clipping is favored. The endonasal corridor may provide a more direct view of limited cerebral vasculature with less brain retraction compared to traditional craniotomy approaches in select cases. As demonstrated in the literature, multiple case reports have documented clipping of intracranial aneurysms in varied locations via the endonasal route without any retraction (Figure 1). Cadaveric studies on the EA reveal that it can provide access to the following limited cerebral vasculature.

Figure 1.

Illustration depicting the location, proportional size, and orientation of intracranial aneurysms treated with an endonasal approach (modified from Wikipedia).

Endonasally Approachable Intracranial Vasculature

a. Paraclinoid Internal Carotid Artery (Figure 2)

Figure 2.

Drawing demonstrating view of intracranial neurovascular structures following endonasal transsellar/transtubercular/transplanar approach with bilateral medial clinoidectomy from a 0° endoscope.

A single cadaveric study on seven specimens with bilateral dissection has demonstrated that the transsellar/transtubercular/transplanar endonasal approach to the paraclinoid region provides excellent visualization of the vasculature[20]. Two case reports describe successful clipping of three paraclinoid aneurysms via the EA without any complication[5, 8]. A temporary lateral pituitary transposition was performed in one such case[5]. Exposure of the cavernous-clinoidal segment of the internal carotid following medial clinoidectomy for proximal control, SHA, and OA was possible in all cadaveric specimens and case reports. Furthermore, the cavernous segment of the internal carotid artery may be accessible with a lateral transsellar approach. Although both case reports note the ability to obtain distal control, the angle that the supraclinoid internal carotid artery creates along the skull base must be carefully studied. The origin of the posterior communicating artery was unable to be visualized in the majority of the cadaveric specimens, likely due to its posterolateral location. As an anatomic reference point, Lai et al. found that vessels anterior to the pituitary stalk could be clipped in nearly all cases with statistical significance; however, only about 1/3 of vasculature posterior to the stalk were accessible. A pituitary transposition may improve the visualization of such vessels[21].

b. Anterior Communicating Artery Complex (Figure 3)

Figure 3.

Drawing demonstrating closer view of intracranial neurovascular structures following endonasal transplanar approach from a 30° angled endoscope.

Although multiple cadaveric and virtual reality studies have demonstrated limitations in visualization of ACoA complex from the EA, two case reports demonstrate that this corridor can be successful and safe [9, 10, 22-24]. The transtuberculum-transplanum approach allows for an upward trajectory to access the lamina terminalis cistern inferiorly[10, 22]. If an EA is to be considered, anterosuperiorly pointing ACoA aneurysms that are directed orthogonal to the EA plane may be more favorable as the neck of the aneurysm will be accessible prior to exposure of the dome. Endoscopic endonasal cadaveric studies have noted that visualization of the anterior communicating artery complex was possible, including the immediate pre-communicating and post-communicating segments of the anterior cerebral arteries (A1 and A2), the anterior communicating artery (ACoA), the proximal recurrent artery of Huebner, and the proximal frontopolar artery[22, 23]. However, further studies have noted that the A2 segment of the anterior cerebral artery was accessible in only 40% of specimens, adding significant concern to the ability to obtain distal control from this corridor. The anterior, superior and inferior aspects of the ACoA are visible, but the posterior aspect can be difficult to fully appreciate[24]. Perforating vessels off the posterior aspect of the ACoA complex must be fully appreciated and avoided during clipping; poor visualization of this area may preclude safe clipping from this route. Furthermore, in the setting of a prefixed chiasm and temporary clip placement, there will be less space for neurovascular dissection and exploration in an already confined exposure. The considerable variability of the complex and optic apparatus, the varied and often hidden portions of the pre-communicating segments, poor visualization of the posterior perforators, and cadaveric studies demonstrating limited A2 exposure for potential distal control add significant limitations to this approach.

c. Midline Posterior Circulation (Figures 4 and 5)

Figure 4.

Drawing demonstrating view of intracranial neurovascular structures following endonasal transsellar and upper transclival approach with posterior clinoidectomy and pituitary transposition from a 0° endoscope.

Figure 5.

Drawing demonstrating view of intracranial neurovascular structures following endonasal mid- and lower transclival approaches from a 0° endoscope. A microdissector is used to show the posterolateral position of the proximal PICA.

A cadaveric study on endoscopic endonasal transclival approaches on 11 specimens has shown, with limitation, the ability to expose the upper midline posterior circulation, extending from the anterior inferior cerebellar artery (AICA) takeoff, observed in 100% of specimens, to the basilar bifurcation, accessed in 64% of specimens[25]. The vertebral artery and vertebrobasilar (VBJ) junction could be exposed in less than half of the specimens through this approach. Removal of the medial occipital condyle and C1 medial superior articular facet may provide additional inferior visualization and has been reported[7]. Aggressive bony removal in this location will be tempered by destabilizing the occipital-cervical junction. Reports have shown the ability to clip a proximal right superior cerebellar artery aneurysm, a left mid-basilar trunk aneurysm, a right vertebral artery/PICA aneurysm, and a thrombosed right vertebral artery aneurysm[3, 4, 6, 7]. The relationship of the posterior circulation to the clivus has considerable variation, and exposure of the entire basilar artery may not be possible. Meticulous review of preoperative imaging must be performed to determine if this approach will generate enough vascular exposure. Furthermore, the paraclival carotid arteries limit lateral exposure. Extensive hemorrhage from the venous basilar plexus can occur following bony removal, and significant attention must be given to obtaining hemostasis prior to opening the dura. Intraoperative Doppler ultrasound and imaging review may help identify the precise location of the underlying vasculature prior to opening the dura. Dural reconstruction of the posterior fossa must be performed meticulously to minimize the risk of postoperative CSF leak. A firm understanding of these limitations must be kept in mind; however, the ventral corridor does provide the advantage of visualization and minimal to no retraction, and, in the setting of poor endovascular options, a small, laterally projecting mid-trunk basilar artery aneurysm necessitating treatment may be the most favorable aneurysm for this approach in experienced hands.

Basic tenets of cerebrovascular neurosurgery, including the ability to have proximal and distal control and good visualization, have been noted within the discussed small number of case examples. Described advantages of the EA include illumination, panoramic view enhancing visualization, minimal to no brain retraction, and reduced tissue manipulation. The utility of neurophysiological monitoring and post-clipping intraoperative angiography have been described after traditional craniotomy for aneurysm clipping and can also be performed following this approach[26, 27]. Although indocyanine green fluorescence has been described during general endonasal endoscopy and its utility has been well described after transcranial aneurysm surgery, its intraoperative use after EA clipping has not been described and may be an alternative to angiography in this rare setting[28, 29]. Low rates of infection from the EA have been reported in general, likely due to the judicious use of antibiotics, significant irrigation during surgery, and good reconstruction[30].

Significant limitations are present through EAs that prevent this corridor approach from gaining broader treatment consideration except on very particular aneurysms. Commonly described limitations of this technique include aneurysm orientation and location, narrow exposure, requirement of lower profile aneurysm clips and appliers, and challenges with handling potential intraoperative rupture.

The morphology and location of the aneurysm must be amenable to an approach with accessibility to only midline structures from an inferior trajectory. Small, midline aneurysms with necks that are orthogonal to the plane of approach, such as anterosuperiorly pointing ACoA aneurysms or laterally pointing mid-trunk basilar aneurysms may be the most favorable aneurysms within the limited EA corridor. Furthermore, proximal and distal control should always be obtained, and this requires exposure of parent vasculature that can have considerable variation and may not be possible from this approach. Placement of temporary clips may further reduce the working room in an already confined corridor and prevent good visualization of neurovascular structures. Lower profile technology with greater degrees of freedom, including clips and single-shaft applicators, may help address this limitation.

The ability to control aneurysmal rupture and/or arterial hemorrhage without vessel injury or sacrifice from the EA will likely be difficult to achieve. Internal carotid artery injury from a series of 2,015 endonasal skull base surgeries has been noted to occur more commonly on the left side and leads to high rates of vessel sacrifice[31]. Of the 9 aneurysms treated with the EA, 7 were right-sided aneurysms. Although intraoperative rupture was controlled without complication in one case, the necessity for emergent additional suction within a narrow field, the possibility of having to remove the endoscope for repetitive lens cleaning, and the need for emergent endovascular intervention should be considered. Furthermore, the current inability to have a vascular bypass as an option through the EA must be contemplated.

Robust dural reconstruction is paramount after the EA for aneurysm clipping. Pedicled vascularized nasoseptal flaps have dramatically lowered the CSF leak rate after endonasal surgery in general[32]. However, in the setting of subarachnoid hemorrhage and potential communicating hydrocephalus or elevated intracranial pressure, meticulous attention towards dural reconstruction is needed. Additionally, the higher profile of current aneurysm clips may prevent good reconstruction or lead to delayed flap ischemia, and clip size needs to be considered in advance of surgical clipping. While clip configuration in the setting of potential residual or recurrent aneurysm may preclude a repeat EA, long-term scarring between the clip hub and dural reconstruction may increase the complexity of delayed flap takedown.

Conclusion

The EA for surgically clipping intracranial aneurysms is provocative, and the discussed considerable limitations should temper unbridled enthusiasm with this approach. Furthermore, given the steep learning curve, limited experience, and low numbers of candidate aneurysms that are suboptimal for endovascular coiling or craniotomy yet amenable to the endonasal route, this approach should only be considered by very experienced teams in endoscopic skull base and cerebrovascular surgery. Additional cadaveric studies, careful review of preoperative imaging, and experience will more strongly define ideal aneurysms for the EA.

Table 2.

Aneurysm Clipping

| Report | Aneurysm Location | Approach | Module | Clip Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Early endoscopic aneurysm clippings | ||||

| Kassam 2006 | R. VA | Endoscopic (Aneurysmorrhaphy) | Transclival, medial occipital chondylectomy, medial C1 facetectomy | Curved microclip |

| Kassam 2007 | L. SHA | Endoscopic with simultaneous craniotomy for L. ACoA aneurysm | Transplanar–transsellar | Curved clip × 2 |

| Kitano 2007 | ACoA | Endoscopic - Sublabial | Extended transphenoidal | Sugita side-curved miniclip |

| Eloy 2008 | BA trunk | Endoscopic assisted - Sublabial | Transphenoidal-transclival | Low-profile Weck clip |

| Endoscopic endonasal aneurysm clippings | ||||

| Germanwala 2011 | R. ICA Paraclinoidal | Endoscopic | Transplanar-transsellar | 7-mm straight Yasargil clip |

| R. OA | Endoscopic | Transplanar-transsellar | 5-mm straight Yasargil clip | |

| Ensenat2011 | R. VA-PICA | Endoscopic | Transphenoidal-transclival | Curved Yasargil clip |

| Froelich 2011 | ACoA | Endoscopic | transplanum-transtuberculum | 7-mm straight Yasargil clip |

| Drazin 2012 | R. BA-SCA | Endoscopic | transsphenoidal/transclival-transsellar | Straight Yasargil miniclip ×2 |

Acknowledgements

This research was supported in part by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH/NINDS.

Abbreviations

- EA

Endonasal Approach

- EEA

Endoscopic Endonasal Approach

- SHA

Superior Hypophyseal Artery

- OA

Ophthalmic Artery

- ACoA

Anterior Communicating Artery

- PICA

Posterior Inferior Cerebellar Artery

- AVM

Arteriovenous Malformation

- AICA

Anterior Inferior Cerebellar Artery

- VBJ

Vertebrobasilar Junction

- ON

Optic Nerve

- OC

Optic Chiasm

- CA

Carotid Artery

- PG

Pituitary Gland

- PS

Pituitary Stalk

- LT

Lamina Terminalis

- OMN

Oculomotor Nerve

- PCA

Posterior Cerebral Artery

- MB

Mammillary Body

- ASA

Anterior Spinal Artery

- VA

Vertebral Artery

- BA

Basilar Artery

- A1

A1 segment of the Anterior Cerebral Artery

- A2

A2 segment of the Anterior Cerebral Artery

- Mm

Millimeters

- CSF

Cerebrospinal Fluid

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Financial disclosure/conflict of interest

The authors have no financial disclosure or conflict of interest pertaining to any of the drugs, materials, and/or devices discussed in this report.

References

- 1.Pant H, Bhatki AM, Snyderman CH, Vescan AD, Carrau RL, Gardner P, et al. Quality of life following endonasal skull base surgery. Skull base : official journal of North American Skull Base Society [et al] 2010;20:35–40. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1242983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kassam AB, Prevedello DM, Carrau RL, Snyderman CH, Thomas A, Gardner P, et al. Endoscopic endonasal skull base surgery: analysis of complications in the authors' initial 800 patients. Journal of neurosurgery. 2011;114:1544–68. doi: 10.3171/2010.10.JNS09406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eloy JA, Carai A, Patel AB, Genden EM, Bederson JB. Combined endoscope-assisted transclival clipping and endovascular stenting of a basilar trunk aneurysm: case report. Neurosurgery. 2008;62:142–3. doi: 10.1227/01.neu.0000317385.91432.df. discussion 3-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Drazin D, Zhuang L, Schievink WI, Mamelak AN. Expanded endonasal approach for the clipping of a ruptured basilar aneurysm and feeding artery to a cerebellar arteriovenous malformation. Journal of clinical neuroscience : official journal of the Neurosurgical Society of Australasia. 2012;19:144–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2011.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Germanwala AV, Zanation AM. Endoscopic endonasal approach for clipping of ruptured and unruptured paraclinoid cerebral aneurysms: case report. Neurosurgery. 2011;68:234–9. doi: 10.1227/NEU.0b013e318207b684. discussion 40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ensenat J, Alobid I, de Notaris M, Sanchez M, Valero R, Prats-Galino A, et al. Endoscopic endonasal clipping of a ruptured vertebral-posterior inferior cerebellar artery aneurysm: technical case report. Neurosurgery. 2011:69. doi: 10.1227/NEU.0b013e318223b637. onsE121-7; discussion onsE7-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kassam AB, Mintz AH, Gardner PA, Horowitz MB, Carrau RL, Snyderman CH. The expanded endonasal approach for an endoscopic transnasal clipping and aneurysmorrhaphy of a large vertebral artery aneurysm: technical case report. Neurosurgery. 2006:59. doi: 10.1227/01.NEU.0000220047.25001.F8. ONSE162-5; discussion ONSE-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kassam AB, Gardner PA, Mintz A, Snyderman CH, Carrau RL, Horowitz M. Endoscopic endonasal clipping of an unsecured superior hypophyseal artery aneurysm. Technical note. Journal of neurosurgery. 2007;107:1047–52. doi: 10.3171/JNS-07/11/1047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kitano M, Taneda M. Extended transsphenoidal approach to anterior communicating artery aneurysm: aneurysm incidentally identified during macroadenoma resection: technical case report. Neurosurgery. 2007;61:E299–300. doi: 10.1227/01.neu.0000303984.26999.a9. discussion E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Froelich S, Cebula H, Debry C, Boyer P. Anterior communicating artery aneurysm clipped via an endoscopic endonasal approach: technical note. Neurosurgery. 2011;68:310–6. doi: 10.1227/NEU.0b013e3182117063. discussion 5-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kalavakonda C, Sekhar LN, Ramachandran P, Hechl P. Endoscope-assisted microsurgery for intracranial aneurysms. Neurosurgery. 2002;51:1119–26. doi: 10.1097/00006123-200211000-00004. discussion 26-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fischer G, Oertel J, Perneczky A. Endoscopy in aneurysm surgery. Neurosurgery. 2012;70:184–90. doi: 10.1227/NEU.0b013e3182376a36. discussion 90-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Peris-Celda M, Da Roz L, Monroy-Sosa A, Morishita T, Rhoton AL., Jr Surgical anatomy of endoscope-assisted approaches to common aneurysm sites. Neurosurgery. 2014;10(Suppl 1):121–44. doi: 10.1227/NEU.0000000000000205. discussion 44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Spetzler RF, McDougall CG, Albuquerque FC, Zabramski JM, Hills NK, Partovi S, et al. The Barrow Ruptured Aneurysm Trial: 3-year results. Journal of neurosurgery. 2013;119:146–57. doi: 10.3171/2013.3.JNS12683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McDonald JS, McDonald RJ, Fan J, Kallmes DF, Lanzino G, Cloft HJ. Comparative effectiveness of unruptured cerebral aneurysm therapies: propensity score analysis of clipping versus coiling. Stroke; a journal of cerebral circulation. 2013;44:988–94. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.111.000196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brinjikji W, Rabinstein AA, Lanzino G, Kallmes DF, Cloft HJ. Patient outcomes are better for unruptured cerebral aneurysms treated at centers that preferentially treat with endovascular coiling: a study of the national inpatient sample 2001-2007. AJNR American journal of neuroradiology. 2011;32:1065–70. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A2446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Smith GA, Dagostino P, Maltenfort MG, Dumont AS, Ratliff JK. Geographic variation and regional trends in adoption of endovascular techniques for cerebral aneurysms. Journal of neurosurgery. 2011;114:1768–77. doi: 10.3171/2011.1.JNS101528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Raja PV, Huang J, Germanwala AV, Gailloud P, Murphy KP, Tamargo RJ. Microsurgical clipping and endovascular coiling of intracranial aneurysms: a critical review of the literature. Neurosurgery. 2008;62:1187–202. doi: 10.1227/01.neu.0000333291.67362.0b. discussion 202-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sluzewski M, Bosch JA, van Rooij WJ, Nijssen PC, Wijnalda D. Rupture of intracranial aneurysms during treatment with Guglielmi detachable coils: incidence, outcome, and risk factors. Journal of neurosurgery. 2001;94:238–40. doi: 10.3171/jns.2001.94.2.0238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lai LT, Morgan MK, Snidvongs K, Chin DC, Sacks R, Harvey RJ. Endoscopic endonasal transplanum approach to the paraclinoid internal carotid artery. Journal of neurological surgery Part B, Skull base. 2013;74:386–92. doi: 10.1055/s-0033-1347370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kassam AB, Prevedello DM, Thomas A, Gardner P, Mintz A, Snyderman C, et al. Endoscopic endonasal pituitary transposition for a transdorsum sellae approach to the interpeduncular cistern. Neurosurgery. 2008;62:57–72. doi: 10.1227/01.neu.0000317374.30443.23. discussion -4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cavallo LM, de Divitiis O, Aydin S, Messina A, Esposito F, Iaconetta G, et al. Extended endoscopic endonasal transsphenoidal approach to the suprasellar area: anatomic considerations-- part 1. Neurosurgery. 2007;61:24–33. doi: 10.1227/01.neu.0000289708.49684.47. discussion -4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Di Somma A, de Notaris M, Stagno V, Serra L, Ensenat J, Alobid I, et al. Extended endoscopic endonasal approaches for cerebral aneurysms: anatomical, virtual reality and morphometric study. BioMed research international. 2014;2014:703792. doi: 10.1155/2014/703792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lai LT, Morgan MK, Dalgorf D, Bokhari A, Sacks PL, Sacks R, et al. Cadaveric study of the endoscopic endonasal transtubercular approach to the anterior communicating artery complex. Journal of clinical neuroscience : official journal of the Neurosurgical Society of Australasia. 2014;21:827–32. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2013.07.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lai LT, Morgan MK, Chin DC, Snidvongs K, Huang JX, Malek J, et al. A cadaveric study of the endoscopic endonasal transclival approach to the basilar artery. Journal of clinical neuroscience : official journal of the Neurosurgical Society of Australasia. 2013;20:587–92. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2012.03.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bacigaluppi S, Fontanella M, Manninen P, Ducati A, Tredici G, Gentili F. Monitoring techniques for prevention of procedure-related ischemic damage in aneurysm surgery. World neurosurgery. 2012;78:276–88. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2011.11.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tang G, Cawley CM, Dion JE, Barrow DL. Intraoperative angiography during aneurysm surgery: a prospective evaluation of efficacy. Journal of neurosurgery. 2002;96:993–9. doi: 10.3171/jns.2002.96.6.0993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Roessler K, Krawagna M, Dorfler A, Buchfelder M, Ganslandt O. Essentials in intraoperative indocyanine green videoangiography assessment for intracranial aneurysm surgery: conclusions from 295 consecutively clipped aneurysms and review of the literature. Neurosurgical focus. 2014;36:E7. doi: 10.3171/2013.11.FOCUS13475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Litvack ZN, Zada G, Laws ER., Jr. Indocyanine green fluorescence endoscopy for visual differentiation of pituitary tumor from surrounding structures. Journal of neurosurgery. 2012;116:935–41. doi: 10.3171/2012.1.JNS11601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brown SM, Anand VK, Tabaee A, Schwartz TH. Role of perioperative antibiotics in endoscopic skull base surgery. The Laryngoscope. 2007;117:1528–32. doi: 10.1097/MLG.0b013e3180caa177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gardner PA, Tormenti MJ, Pant H, Fernandez-Miranda JC, Snyderman CH, Horowitz MB. Carotid artery injury during endoscopic endonasal skull base surgery: incidence and outcomes. Neurosurgery. 2013;73:261–9. doi: 10.1227/01.neu.0000430821.71267.f2. discussion 9-70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Patel MR, Stadler ME, Snyderman CH, Carrau RL, Kassam AB, Germanwala AV, et al. How to choose? Endoscopic skull base reconstructive options and limitations. Skull base : official journal of North American Skull Base Society [et al] 2010;20:397–404. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1253573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]