Abstract

Rats learn to self-administer intravenous heroin; well-trained animals lever-press at a slow and regular pace over a wide range of intravenous doses. The pauses between successive earned infusions are proportional to the dose of the previous injection and are thought to reflect periods of drug satiety. Rats will also self-administer opiates by microinjection directly into sites in the posterior regions of the ventral tegmentum. To determine if the pauses between self-administered intravenous injections are due to opiate actions in posterior ventral tegmentum, we delivered supplemental morphine directly into this region during intravenous self-administration sessions in well-trained rats. Reverse dialysis of morphine into the posterior ventral tegmentum increased the intervals between earned injections. The inter-response intervals were greatest for infusion into the most posterior ventral tegmental sites, sites in a region variously known as the tail of the ventral tegmental area or as the rostromedial tegmental nucleus. These sites at which morphine prolongs inter-response intervals, correspond to the sites at which opiates have been found most effective in reinforcing instrumental behavior.

Keywords: anterior VTA, cocaine, drug reinforcement, microdialysis, drug satiety

1. Introduction

The reinforcing effects of opiates are thought to rely primarily on their ability to activate opioid receptors in the ventral tegmentum. Rats quickly learn to self-administer morphine (Bozarth & Wise, 1981a; Welzl et al., 1989; Devine & Wise, 1994) and mu (Devine & Wise, 1994; Zangen, Ikemoto, Zadina, & Wise, 2002) and delta (Devine & Wise, 1994) opioids into the ventral tegmental area (VTA), and into a region just caudal to it identified by some as the “tail” of the VTA (tVTA:(Perrotti et al., 2005) and by others as the rostromedial tegmental nucleus (RMTg:(Jhou, Fields, Baxter, Saper, & Holland, 2009). Rats learn to self-administer intravenous heroin (di-acetyl morphine) which is metabolized to morphine as it crosses the blood-brain barrier. Morphine then acts, presumably in this region to inhibit GABAergic neurons that normally hold VTA dopamine neurons under inhibitory control (Jhou et al., 2009; Johnson & North, 1992; Margolis, Hjelmstad, Fujita, & Fields, 2014). Heroin is thought to be more addictive than its metabolite morphine because it crosses the blood-brain barrier more readily than morphine (Oldendorf, Hyman, Braun, & Oldendorf, 1972); when heroin is injected, however, it is the metabolite, morphine, that binds to opioid receptors, disinhibits the dopamine system, and activates the reward system (Bozarth & Wise, 1981a; Phillips & LePiane, 1980).

Rats self-administer heroin and psychomotor stimulants intravenously, and this behavior is characterized (over the working range of doses per injection) by regular inter-response intervals that reflect the time to metabolize what has already been taken (Dougherty & Pickens, 1974; Gerber & Wise, 1989; Yokel & Pickens, 1974). The spacing of the injections appears to reflect periods of drug satiety (Wise, 1987). In the present study we sought to determine if the periods of apparent satiety could be increased by infusions of morphine directly into sites where the drug is thought to have its primary rewarding effects. Thus we assessed the temporal pattern of responding for intravenous heroin in well-trained rats following reverse dialysis of morphine or artificial cerebrospinal fluid (aCSF) into a range of ventral tegmental sites.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals and Surgery

Thirteen male Long-Evans rats (Charles River, Raleigh, NC) weighing 275-325 grams at the time of surgery were used. Each rat was individually housed under a reverse light-dark cycle (12/12, lights off at 8 am) with free access to food and water. All experiments were performed in accordance with the guidelines outlined in the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of the NIDA Intramural Research Program. Each rat was anesthetized first with a combination of ketamine and xylazine (57 mg/kg and 9 mg/kg i.p., respectively). Anesthesia was then maintained during the surgery with isoflurane (2-3% in 1 L/min oxygen). An intravenous microrenathane catheter (Braintree Scientific; Braintree, MA) was first inserted into the right external jugular vein. Catheter tubing was attached to a cannula adaptor fixed to the rat’s skull. Catheters were flushed daily with heparin (10 USP/ml in sterile saline), containing gentamicin (0.08 mg/ml).

Each rat was also implanted, during the same surgery, with bilateral guide cannulae (CMA-11) for microdialysis. To avoid puncture of the midsagittal sinus, guide cannulae were angled at 12° the midline. Guide cannulae were aimed at each of three levels of the ventral tegmentum: anterior VTA (AP −5.0, ML ± 2.4, DV −8.0), the posterior VTA (AP −6.00, ML ± 2.1, DV −7.6) or the tVTA/RMTg (AP −6.8, ML ±2.3, DV - 7.4; Paxinos & Watson 2007).

2.2. Drug.s

Ketamine, xylazine, and 3,6-diacetylmorphine hydrochloride (heroin), and morphine sulphate were obtained from the NIH. Heroin was dissolved in 0.9% sterile saline. Morphine sulphate was dissolved in artificial cerebrospinal fluid (aCSF).

2.3. Heroin intravenous self-administration

2.3.1. Apparatus

Operant conditioning chambers, measuring 25 × 27 × 30 cm were used. Each chamber was equipped with two response levers (one retractable lever and a stationary), a red house light, and a white cue light located above the retractable lever. Chambers were housed within sound-attenuating enclosures equipped with fans that provided both ventilation and a constant source of masking noise.

2.3.2. Drug self-administration procedure

Each rat was housed and trained in a dedicated operant chamber throughout the experiment with food and water available ad libitum. Daily 4-hour intravenous heroin self-administration training sessions began 7-10 days after i.v. catheter and guide cannulae implantation and lasted for 13-15 days. For each rat the head-mount catheter was connected to an infusion line attached to a liquid swivel that allowed for free movement of the rat within the operant chamber. The beginning of each daily training session was signaled by insertion of the retractable response lever into the operant chamber. For the first 7 training sessions each rat was allowed to self-administer intravenous heroin at 0.1 mg/kg/infusion under a fixed ratio 1 schedule of reinforcement with a 20-s time-out period accompanied by illumination of a white cue light located above the retractable lever. Lever presses during the time-out period were recorded but were not reinforced. Presses on the stationary lever were recorded but had no programmed consequence. At the end of the training session the retractable lever was withdrawn from the chamber and the house light was turned off. For training sessions 8-12 and for training sessions 13-15 each rat was allowed to self-administer 0.05 and 0.025 mg/kg/infusions, respectively.

2.4. Morphine reverse dialysis

Immediately following the last training session rats were lightly anesthetized with isoflurane and microdialysis probes with 1 mm active membrane (CMA 11) were bilaterally inserted into the respective brain sites. The probes were continuously perfused with artificial cerebrospinal fluid (aCSF: composition in mM: NaCl, 148; KCl, 2.7; CaCl2, 1.2; MgCl2, 0.8, pH 7.4) at a rate of 0.5μl/min overnight. The flow rate was increased to 2μl/min 1 hr prior to the beginning of the testing session on the next day. On each of the following two days, the rats were allowed to self-administer heroin (0.025 mg/kg/infusion) in 6-hr sessions. During the first 2 hrs of each session the rats received aCSF by reverse dialysis. During the next 4 hrs of each session, the rats either continued to receive aCSF or received 10 mM morphine by reverse dialysis; the opposite treatment was given on the second day with sequence counterbalanced across animals. Flow rate was decreased to 0.5μl/min between sessions and was restored to 2μl/min one hour prior to the second session. The 10 mM dose of morphine was chosen as we found little effect of a 1mM morphine dose on intravenous heroin self-administration in pilot studies.

2.5. Histology

Following completion of behavioral testing, each rat was deeply anesthetized with a mixture of pentobarbital (30 mg/kg, i.p.) and chloral hydrate (140 mg/kg, i.p.) and transcardially perfused with 0.1 M phosphate buffer (PB) followed by 4% (W/V) paraformaldehyde in 0.1 M PB, pH 7.3. The brains were removed and left in 4% paraformaldehyde for 2 hours at 4 °C and then transferred to an 18% sucrose solution in PB. Coronal sections (40 μm) were prepared for each rat and mounted on to gelatin-coated slides. Sections were stained with cresyl violet and microdialysis probe locations were examined using a light microscope.

2.6. Data Analysis

Intravenous heroin self-administration data were analyzed for the self-administration training period using repeated-measures Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) with the i.v. heroin DOSE (0.1, 0.05, 0.025 mg/kg/inf) as the only factor. Significant main effects were further analyzed using Fisher’s LSD post-hoc test. The relation between probe distance (mm caudal from bregma) and i.v. heroin intake for each time period following reverse dialysis of morphine was analyzed by ANOVA and by correlational analysis. In the ANOVA, intended stereotaxic PLACEMENT (aVTA, pVTA, RMTg) and TIME (the first two hour [0-120 min] baseline period, and the last three hour [180-360 min] period of stable responding) were included as between-subjects and within-subjects factors, respectively. The one-hour transition period (120-180 min) was not included in the analysis on the basis of our previous findings (Suto & Wise, 2011) that it takes a similar period for the effects on intravenous cocaine self-administration to stabilize when dopamine agonists are infused into nucleus accumbens by reverse dialysis.

3. Results

3.1. Histology

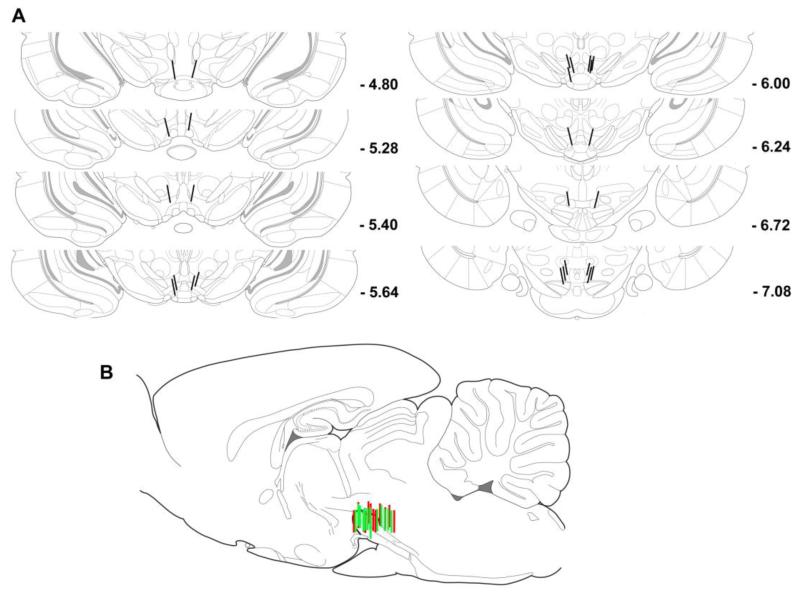

The dialysis probes were distributed throughout the rostro-caudal extent of the ventral tegmentum, ranging from AP −4.80 to AP −7.08 (Fig. 1 A). Placements are reconstructed in sagittal section in Fig. 1B.

Figure 1.

Probe placements in the ventral tegmentum. Lines indicate the locations of the active portion (1.0 mm) of dialysis probes. Drawings are adapted from Paxinos and Watson (2007). A. Probe placements shown on coronal sections. Numbers next to sections indicate the distance (mm) posterior to bregma. B. Probe placements from (A) are reconstructed on a single representative sagittal section (M-L 0.90) to illustrate the rostro-caudal extent of ventral tegmentum placements. Left hemisphere probes are shown in red and right hemisphere probes are shown in green.

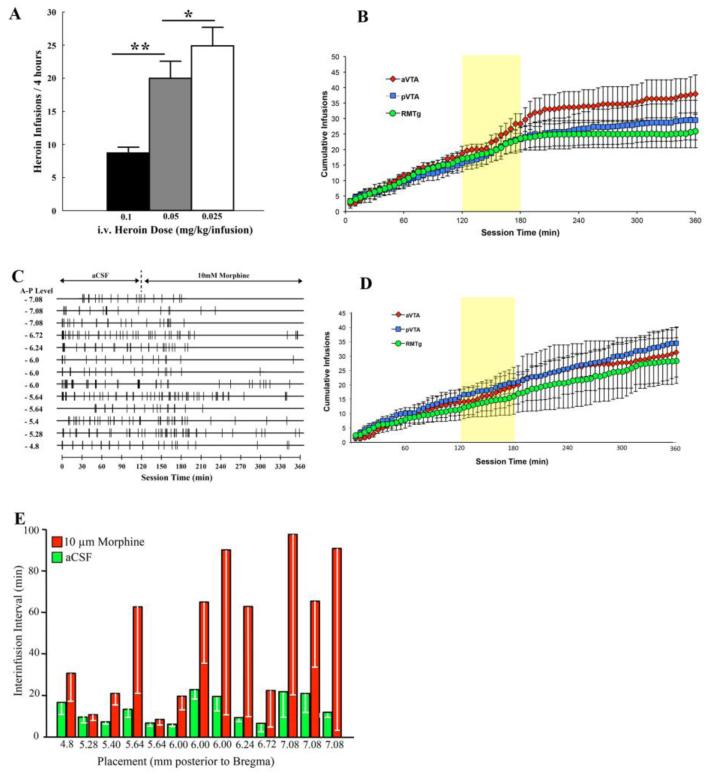

3.2. Heroin self-administration training

Rate of responding became reliable within a few days of training and was inversely related to dose per injection (Figure 2A; main effect of DOSE [F2, 24 = 35.57, p < 0.00001]; Fisher’s LSD post-hoc test showed greater numbers of infusions at the 0.05 mg/kg/inf dose relative to the 0.1 mg/kg/inf dose [p < 0.0001] and at the 0.025 mg/kg/inf dose relative to the 0.1 mg/kg/inf dose [p < 0.000001] and the 0.05 mg/kg/inf dose [p < 0.05]). All rats showed stable levels of heroin self-administration (< 10% variation in daily intake) by the end of the training period, making approximately 6 responses per hour for the dose of 0.025 mg/kg/injection.

Figure 2.

Effects of bilateral perfusion of morphine (10 mM) into the ventral tegmentum on intravenous heroin self-administration in well-trained rats. A. Self-administration training: During the training period rats adjusted the number of earned heroin infusions according to the available dose of i.v. heroin (* p < 0.05, ** p < 0.000001). B. Cumulative earned heroin infusions for rats with probe placements aimed at the anterior (aVTA), posterior (pVTA) or most posterior (RMTg) portions ventral tegmentum before (0-120 min) and after (120-360 min) reverse dialysis of 10 mM morphine during a 6-hr i.v. heroin self-administration session (0.025 mg/kg/inf). The shaded yellow area highlights the first hour (120-180min) of morphine reverse dialysis, a transition period during which response rates stabilized at new levels (not included for statistical analysis). C. Event records for individual rats (n = 13) before (0-120 min) and after (120-360 min) onset of reverse dialysis of 10 mM morphine during a 6-hr i.v. heroin self-administration session (0.025 mg/kg/inf). Numbers to left of individual event records indicate confirmed dialysis probe distance (in mm) posterior to bregma for individual rats. Vertical tick lines on individual event records indicate the times of earned heroin infusions. Intracranial reverse dialysis of morphine generally decreased the rate of i.v. heroin self-administration and this effect became evident beginning after approximately 1-hr of reverse dialysis of morphine. D. Cumulative earned heroin infusions for rats with probe placements aimed at the anterior (aVTA), posterior (pVTA) or most posterior (RMTg) portions ventral tegmentum during reverse dialysis of aCSF during a 6-hr i.v. heroin self-administration session (0.025 mg/kg/inf). The shaded yellow area is included to facilitate comparisons to response rates during the first hour of morphine reverse dialysis shown in (B). E. Mean inter-infusion intervals (−SEM) for individual rats during the last three hours of morphine infusion (red bars) or continuous aCSF (green bars) infusion. Because interinfusion intervals were very large for the morphine condition, error bars are shown only in downward deflection. The extreme variation between inter-response intervals are not unusual and reflect cumulative regulation of blood levels. When one interval is unusually long, the next interval will be unusually short in compensation. While the inter-response times can be irregular, the total hourly intake is remarkably constant.

3.3. Intracranial reverse dialysis of morphine

Response rates became unstable over the first hour of continuous morphine, but not aCSF, infusion (Figs 2B and 2D) and restabilized, again becoming linear and settling at mean rates of 2.5 or less in the last three hours of testing (Fig. 2B). This was reflected in a main effect of TIME (F59, 590 = 58.08, p < 0.000001) in an analysis of variance comparing mean intake of the three groups for the baseline period (first two hours) and the stable portion (last three hours) of the treatment period (Fig 2C). While the interaction between TIME and intended stereotaxic PLACEMENT did not reach statistical significance (F2, 20 = 0.74, p = 0.5), inter-response times during the last three hours were significantly correlated with actual anterior-posterior probe placement (r=0.61, P < 0.05, Fig. 2E). Mean inter-infusion intervals and actual anterior-posterior probe placement were not significantly correlated in the baseline period or the transition period. During continuous aCSF infusion response rates were stable throughout the testing session (Fig. 2D).

4. Discussion

The present results confirm that morphine actions at opiate receptors in the ventral tegmentum—a region where opiates have known rewarding actions—contribute significantly to the regular pauses between earned intravenous heroin injections. Reverse dialysis of morphine into this region increased post-reinforcement pauses, resulting in an overall reduction of heroin intake. With opiate drugs, as well as with stimulant drugs, the post-reinforcement pause is thought to reflect a period of drug satiety following receipt of the previous drug infusion (Gerber & Wise, 1989). Reverse dialysis of morphine into the ventral tegmentum appears to summate with earned intravenous heroin to extend the periods of satiety between responses.

Our data are consistent with the characterization of the interval between responses of well-trained animals in this model as a reflection of the duration of the rewarding effect of the previous injection (Dougherty & Pickens, 1974; Gerber & Wise, 1989; Wise, 1987; Yokel & Pickens, 1974). The rewarding effects of opiates are linked primarily to the ventral tegmentum; injections in this but not other regions potentiate, with short latency, the rewarding effects of lateral hypothalamic electrical stimulation (Broekkamp et al., 1976) and rats learn to work for morphine injections localized to this region (Bozarth & Wise, 1981b; Devine & Wise, 1994; Jhou, Xu, Lee, Gallen, & Ikemoto, 2012; Welzl, Kuhn, & Huston, 1989; Zangen et al., 2002). The sites where our injections most effectively prolonged inter-response times are the sited where mu opioids are most avidly self-administered (Jhou et al., 2012; Zangen et al., 2002).

The primary mechanism of opiate reward is thought to be the disinhibition of the ventral tegmental dopamine systems resulting from opioid inhibition of nearby GABAergic neurons that normally hold the dopaminergic cells under inhibitory control. Until recently, it was believed that GABAergic neurons involved in this control were interspersed with the dopamine neurons they inhibited (Johnson & North, 1992), in what is known as the ventral tegmental area (VTA), a region of the ventral tegmentum defined originally by nissl staining in the oppossum (Tsai, 1925) and more recently by fluorescence histochemistry (Dahlström & Fuxe, 1964) and tyrosine hydroxylase immunohistochemistry (Swanson, 1982). However, it has recently been suggested that the GABAergic neurons inhibited by opiates that most strongly control the dopamine system are neurons localized just caudal to the classic ventral tegmental area (Jhou et al., 2012); the GABAergic cells of this region are continuous with those of the traditional VTA, and they also project to (Jhou et al., 2009) and inhibit the DA neurons of the VTA (Lecca, Melis, Luchicchi, Muntoni, & Pistis, 2012; Matsui & Williams, 2011). Our data fit most readily with the assumption that GABAergic neurons of the VTA proper and GABAergic neurons just caudal to them each contribute to the rewarding effects of mu opioids. While we cannot rule out the possibility that our more rostral morphine infusions were effective because of diffusion to a more caudal site of action, it is generally assumed that microdialysis significantly affects chemical concentrations within a limited range—perhaps a radius of 250 μm—of the dialysis probe (Borland, Shi, Yang, & Michael, 2005). Moreover, morphine is estimated to diffuse at a rate of approximately 1mm/hr following 0.5 μl microinjections under hydraulic pressure (Broekkamp et al., 1976) and our anterior and posterior probes were over 2mm apart. It might be suggested that responding only settled into the linear final segment of the cumulative records after about 80 minutes of reverse dialysis, whereas linear responding resumed 20-30 minutes earlier for the pVTA and RMTg groups (Fig. 2B). This would not appear to give sufficient time for morphine to diffuse from our aVTA placements to our RMTg placements—2mm apart—as morphine is estimated to diffuse slowly at a rate of approximately 1mm/hr following 0.5 μl microinjections under hydraulic pressure (Broekkamp et al., 1976) and it takes about an hour for drugs infused by reverse dialysis to have significant local effects in this paradigm (Suto & Wise, 2011). When rats self-administering heroin are given supplemental drug in the form of a constant i.v. drip, they decrease their voluntary intake proportionately (Gerber & Wise,1989). In the case of the intracranial supplementary morphine used in the current studies, individual response records (Fig 2C) show near complete cessation of i.v. heroin self-administration in several cases. This is particularly evident for infusions into the most posterior ventral tegmentum placements. Direct comparisons between these studies are, however, complicated. In studies using supplementary i.v. heroin (Gerber & Wise, 1989) the doses chosen were based on the rats’ established self-administered i.v. heroin intake. In the present study the brain concentration of drug resulting from neither the earned i.v. injections or the supplemental reverse dialysis infusions is known. It is possible that ventral tegmentum morphine doses below 10 mM would reveal additive effects with self-administered i.v. heroin that are more similar to those observed with supplementary i.v. heroin. In any case, it is unlikely that the reduced responding caused by ventral tegmental morphine infusion in the present experiments was due to some kind of performance impairment. Broekkamp et al. (1976) have shown that morphine injections into the ventral tegmentum enhance response rates when rats are working for intracranial electrical stimulation rather than for intravenous heroin injections. Such injections also increase locomotor activity (Joyce & Iversen, 1979), presumably by disinhibiting the dopamine system (Holmes & Wise, 1985; Iwamoto & Way, 1977). The sedative effects of morphine are localized to a region in the central pons, 3-4 mm caudal to the most caudal probe placement in the present study (Broekkamp, LePichon, & Lloyd, 1984).

In summary, the present results suggest that morphine satisfies the motivation to self-administer intravenous heroin by an action at the same ventral tegmental brain sites where the mu opioids serve to reinforce lever-pressing behavior (Bozarth & Wise, 1981a; Welzl et al., 1989; Zangen et al., 2002: Jhou et al, 2012); thus opiate receptor mechanisms of opiate reward and opiate satiety appear likely to be one and the same. While this might seem self-evident, the best central injection sites for cocaine reinforcement are not the best sites for prolonging cocaine satiety (Suto & Wise, 2011; Suto et al., 2009). Thus, these data suggest an important difference in the organization of brain mechanisms mediating dissociable reinforcement and satiety effects of opiates and of stimulants.

Highlights.

-

-

Ventral tegmental morphine increases the pauses between responses for i.v. heroin.

-

-

Posterior ventral tegmental infusions are most effective

-

-

Ventral tegmental morphine appears to prolong a post-injection heroin satiety state.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute on Drug Abuse, National Institutes of Health, Department of Health and Human Services.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

S Steidl, Intramural Research Program National Institute on Drug Abuse, NIH/DHHS, Baltimore, MD 21224, USA.

S Myal, Intramural Research Program National Institute on Drug Abuse, NIH/DHHS, Baltimore, MD 21224, USA.

RA Wise, Intramural Research Program National Institute on Drug Abuse, NIH/DHHS, Baltimore, MD 21224, USA.

References

- Borland LM, Shi G, Yang H, Michael AC. Voltammetric study of extracellular dopamine near microdialysis probes acutely implanted in the striatum of the anesthetized rat. J Neurosci Methods. 2005;146:149–58. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2005.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bozarth MA, Wise RA. Intracranial self-administration of morphine into the ventral tegmental area in rats. Life Sci. 1981a;28:551–55. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(81)90148-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bozarth MA, Wise RA. Heroin reward is dependent on a dopaminergic substrate. Life Sci. 1981b;29:1881–86. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(81)90519-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broekkamp CLE, LePichon M, Lloyd KG. Akinesia after locally applied morphine near the nucleus raphe pontis of the rat. Neurosci Lett. 1984;50:313–18. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(84)90505-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broekkamp CLE, Van den Bogaard JH, Heijnen HJ, Rops RH, Cools AR, Van Rossum JM. Separation of inhibiting and stimulating effects of morphine on self-stimulation behavior by intracerebral microinjections. Eur J Pharmacol. 1976;36:443–46. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(76)90099-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahlström A, Fuxe K. Evidence for the existence of monoamine-containing neurons in the cenral nervous system. I. Demonstration of monoamines in the cell bodies of brain stem neurons. Acta Physiologica Scandanavica. 1964;62:1–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devine DP, Wise RA. Self-administration of morphine, DAMGO, and DPDPE into the ventral tegmental area of rats. J Neurosci. 1994;14:1978–84. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-04-01978.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dougherty JD, Pickens R. Effects of phenobarbital and SKF 525A on cocaine self administration in rats. Drug Addiction. 1974;3:135–143. [Google Scholar]

- Gerber GJ, Wise RA. Pharmacological regulation of intravenous cocaine and heroin self-administration in rats: a variable dose paradigm. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1989;32:527–31. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(89)90192-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes LJ, Wise RA. Contralateral circling induced by tegmental morphine: anatomical localization, pharmacological specificity, and phenomenology. Brain Res. 1985;326:19–26. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(85)91380-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwamoto ET, Way EL. Circling behavior and stereotypy induced by intranigral opiate microinjections. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1977;203:347–59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jhou TC, Fields HL, Baxter MG, Saper CB, Holland PC. The rostromedial tegmental nucleus (RMTg), a GABAergic afferent to midbrain dopamine neurons, encodes aversive stimuli and inhibits motor responses. Neuron. 2009;61:786–800. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jhou TC, Xu SP, Lee MR, Gallen CL, Ikemoto S. Mapping of reinforcing and analgesic effects of the mu opioid agonist endomorphin-1 in the ventral midbrain of the rat. Psychopharmacology. 2012;224:303–12. doi: 10.1007/s00213-012-2753-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson SW, North RA. Opioids excite dopamine neurons by hyperpolarization of local interneurons. J Neurosci. 1992;12:483–88. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.12-02-00483.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joyce EM, Iversen SD. The effect of morphine applied locally to mesencephalic dopamine cell bodies on spontaneous motor activity in the rat. Neuroscience Letters. 1979;14:207–12. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(79)96149-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lecca S, Melis M, Luchicchi A, Muntoni AL, Pistis M. Inhibitory inputs from rostromedial tegmental neurons regulate spontaneous activity of midbrain dopamine cells and their responses to drugs of abuse. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2012;37:1164–76. doi: 10.1038/npp.2011.302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margolis EB, Hjelmstad GO, Fujita W, Fields HL. Direct Bidirectional mu-Opioid Control of Midbrain Dopamine Neurons. J Neurosci. 2014;34:14707–16. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2144-14.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsui A, Williams JT. Opioid-sensitive GABA inputs from rostromedial tegmental nucleus synapse onto midbrain dopamine neurons. J Neurosci. 2011;31:17729–35. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4570-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oldendorf WH, Hyman S, Braun L, Oldendorf SZ. Blood-brain barrier: Penetration of morphine, codeine, heroin, and methadone after carotid injection. Science. 1972;178:984–86. doi: 10.1126/science.178.4064.984. 1972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perrotti LI, Bolanos CA, Choi KH, Russo SJ, Edwards S, Ulery PG, Wallace DL, Self DW, Nestler EJ, Barrot M. DeltaFosB accumulates in a GABAergic cell population in the posterior tail of the ventral tegmental area after psychostimulant treatment. Eur J Neurosci. 2005;21:2817–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2005.04110.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paxinos G, Watson C. The rat brain in stereotaxic coordinates. Academic Press; San Diego: 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips AG, LePiane FG. Reinforcing effects of morphine microinjection into the ventral tegmental area. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1980;12:965–68. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(80)90460-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swanson LW. The projections of the ventral tegmental area and adjacent regions: A combined fluorescent retrograde tracer and immunofluorescence study in the rat. Brain Res Bull. 1982;9:321–53. doi: 10.1016/0361-9230(82)90145-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai C. The optic tracts and centers of the opossum. Didelphis virginiana. Journal Comp Neurol. 1925;39:173–216. [Google Scholar]

- Suto N, Wise RA. Satiating effects of cocaine are controlled by dopamine actions in the nucleus accumbens core. J Neurosci. 2011;31:17917–22. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1903-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suto N, Ecke LE, Wise RA. Control of within-binge cocaine-seeking by dopamine and glutamate in the core of nucleus accumbens. Psychopharmacology. 2009;205:431–39. doi: 10.1007/s00213-009-1553-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welzl H, Kuhn G, Huston JP. Self-administration of small amounts of morphine through glass micropipettes into the ventral tegmental area of the rat. Neuropharmacology. 1989;28:1017–23. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(89)90112-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wise RA. Intravenous drug self-administration: A special case of positive reinforcement. In: Bozarth MA, editor. Methods of Assessing the Reinforcing Properties of Abused Drugs. Springer-Verlag; New York: 1987. pp. 117–141. [Google Scholar]

- Yokel RA, Pickens R. Drug level of d- and l-amphetamine during intravenous self-administration. Psychopharmacologia. 1974;34:255–64. doi: 10.1007/BF00421966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zangen A, Ikemoto S, Zadina JE, Wise R. Rewarding and psychomotor stimulant effects of endomorphin-1: anteroposterior differences within the ventral tegmental area and lack of effect in the nucleus accumbens. J Neurosci. 2002;22:7225–33. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-16-07225.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]