Abstract

Sphingosine-1-phosphate receptors (S1PRs) are important regulators of vascular permeability, inflammation, angiogenesis and vascular maturation. Identifying a specific S1PR PET radioligand is imperative, but it is hindered by the complexity and variability of current for binding affinity measurement procedures. Herein, we report a streamlined protocol for radiosynthesis of [32P]S1P with good radiochemical yield (36 – 50%) and high radiochemical purity (>99%). We also report a reproducible procedure for determining the binding affinity for compounds targeting S1PRs in vitro.

Keywords: Competitive Binding Assay, Phosphorus-32, Radioligand, Sphingosine 1-Phosphate, Sphingosine 1-Phosphate Receptors, Sphingosine Kinase 1

1. Introduction

Sphingosine 1-Phosphate (S1P) is a potent bioactive lipid that regulates diverse physiological and immunological processes. Most of its best characterized actions are mediated through a family of five G-protein coupled receptors (S1PR1-5) (Rosen et al., 2014). Since the development and approval of FTY720 (Gilenya®, Fingolimod) for oral treatment of relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis (MS), the S1PRs have attracted a great deal of interest (Urbano et al., 2013) Diversity in the expression pattern and the function of S1PRs has been observed in the central nervous system (CNS). S1PR1, S1PR2 and S1PR3 are widely expressed in neurons and glia (no S1PR2 expression in astrocytes and oligodendrocytes), whereas expression of S1PR5 is highly restricted to oligodendrocytes (Soliven et al., 2011). S1PR1 and S1PR3 expression on reactive astrocytes significantly increased in both active and chronic inactive MS lesions (Van Doorn et al., 2010). Consistently, the functional antagonism for S1PRs is partly attributed to the direct neuroprotective effect of FTY720 (O'Sullivan and Dev, 2013).

The S1P/S1PRs pathway also plays an important role in both normal and pathological conditions outside the CNS system. S1PR1 and S1PR3 modulate angiogenesis by enhancing platelets, endothelial cell and vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation and migration, whereas S1PR2 receptors block the cell migration in the cardiovascular system (Swan et al., 2010). FTY720 and other S1PR1/S1PR3 antagonists showed potential atheroprotective effects in animal models of atherosclerosis and neointimal hyperplasia (Keul et al., 2007; Shimizu et al., 2012). Moreover, S1PRs expression levels are associated with tumor growth, cancer staging, as well as patient survival (Kunkel et al., 2013; Yoshida et al., 2010).

Considering the importance of S1PRs in MS and other diseases, development of positron emission tomography (PET) radiotracers targeting specific S1P receptors would provide unique tools to detect the in vivo level of the corresponding receptor, and to monitor the physiopathological progression of these diseases (Inglese and Petracca, 2013; Kiferle et al., 2011; Kipp and Amor, 2012; Miller et al., 2012). Until recently, there have been two radioligands developed that focus on the S1P receptors: BZM055 (Briard et al., 2011), an analogue of FTY-720 that contains an 123I on the aromatic core; and a recently published fluorinated analogue of W146 (Prasad et al., 2014; Sanna et al., 2006). However, the lower brain penetrating capability of [123I]BZM055 and the fast metabolism and defluorination in vivo of [18F]W146 limited their clinical utility.

One of the hindrances for the development of PET agents for imaging S1PRs was a lack of a readily available quantitative binding assay for determining the binding affinity for compounds toward the S1P receptors. The functional assay, based on the downstream signaling responses following the receptor activation, is most commonly used. In the functional assay, the half maximal effective concentration (EC50) represents the binding affinity of compounds, which actually reflects the ability to induce biological effects following the ligand-receptor binding and obviously only works for agonists (Gardner and Strange, 1998). In fact, the most efficient method of screening the binding affinity of novel compounds is with a competitive binding assay, using a ligand that is specific to the desired target protein(s); in this case radiolabeled S1P. While several fluorescently-labeled analogues of S1P have been prepared, none of these have been successfully applied to a binding assay targeting the S1P receptors (Ettmayer et al., 2004; Hakogi et al., 2003; Yamamoto et al., 2008). The radioactive competitive binding assay utilizing radiolabeled S1P provides a reliable measure of the binding affinity; and works equally well for agonists & antagonists (Gardner and Strange, 1998). Notably, a discontinuity between the more common functional assay results and the radioactive competitive binding assay results has been reported (Gardner and Strange, 1998; Hale et al., 2004). In order to carry out our ligand development project, we need to explore a binding assay method that could be performed in our laboratory routinely. We also needed to develop a detailed, reproducible procedure for the preparation of the required radioligand used in the binding assay. Herein, we report a simplified method to reliably produce 32P-radiolabeled S1P, as well as a straightforward method for the competition binding assay.

2. Materials and methods

All reactions were performed in low-retention centrifuge tubes. Unless otherwise stated, all reagents were used as received. [γ-32P]Adenosine triphosphate (ATP) (370 MBq/mL; specific activity = 222 TBq/mmol) was purchased from PerkinElmer (Boston, MA). Recombinant human sphingosine kinase 1 (rhSPHK1) was purchased from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN), upon receipt, it was aliquoted into ten parts diluted with buffer A (vida infra) to a final concentration of 1 μg / 10 μL. S1PR1 membranes that were prepared from Chinese hamster ovary (CHO)-K1 cells expressing recombinant human S1PR1 receptors and were used in the study were purchased from Chan Test Corp. (Cleveland, OH). S1PR2-3 membranes that were prepared from Chem-1, an adherent cell line expressing the promiscuous G-protein, Gα15, were purchased from Merck Millipore (Billerica, MA). All the membrane preparations are crude membrane preparations made from proprietary stable recombinant cell lines to ensure high-level of S1PR1-3 surface expression. The kinase aliquots and membranes were stored at −80 °C until use.

2.1 Establishment of the Calibration Curve

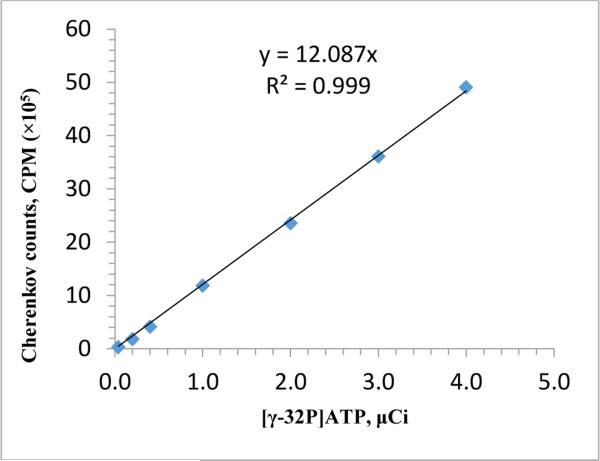

Known volumes (1.48 - 3.7 MBq) of commercially available [γ-32P]ATP were added to scintillation vials and the radioactivity (counts per minute, CPM) was measured by a Beckman LS 3801 scintillation counter using Cherenkov counting. The readout and the calculated radioactivity were plotted to establish the calibration curve (through the origin) and the equation.

2.2 Radiosynthesis of [32P]Sphingosine 1-Phosphate

[32P]S1P was prepared by addition of 12 μL 1 M MgCl2 and 65 μL 1 mM sphingosine in 5% Triton X-100 to a 2 mL low-retention centrifuge tube. 1.0 μg sphingosine kinase 1 in 10 μL Buffer A (100 mM 2-[4-(2-hydroxyethyl)piperazin-1-yl]ethanesulfonic acid (HEPES) [pH 7.5], 10 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetate (EDTA), 1 mM dithiothreitol, protease inhibitor cocktail) was then added to the reaction mixture. The volume was adjusted to 1 mL with sphingosine kinase buffer (20 mM tris(hydroxymethyl)aminomethane (Tris) [pH 7.4], 1 mM EDTA, 0.5 mM 4-deoxypyridoxine, 1 mM β-mercaptoethanol, 1 mM orthovanadate, 40 mM β-glycerophosphate, 10% glycerol, and protease inhibitor cocktail). 8.51 MBq [γ-32P]ATP was then added to the reaction vial, which was mixed by pipette. The reaction was then incubated in a 33-35 °C water bath for 2h, at which time the reaction mixture was divided into two 2 mL centrifuge tubes. To each of these tubes was added 0.5 mL CHCl3, 0.5 mL MeOH, and 50 μL 3 M NaOH(aq). The centrifuge tubes were then vortexed for ~30 seconds and centrifuged for 10 min @ 1500 g to separate the phases. The upper aqueous layer were transferred to 2 mL low-retention centrifuge tubes, 0.5 mL CHCl3 and 100 μL 12M HCl were added to each tube. The tubes were vortexed for ~30 seconds and then centrifuged for 10 min @ 1500 g to separate the phases. The upper aqueous layers were removed and discarded. The lower organic layers were combined and reduced under a stream of N2(g) to give the [32P]S1P. The [32P]S1P was then dissolved in 500 μL of dimethylsulfoxide and transferred to a low-retention centrifuge tube for storage. Aliquots of 1, 2, and 3 μL were removed and the radioactive yield was determined by Cerenkov counting (Beckman LS 3801 scintillation counter) to be 3.7 MBq using the calibration curve described above. The radioactive purity was determined by radio TLC eluting with a n-Butanol/Acetic Acid/Water (3/1/1, v/v/v) solvent system. The desired [32P]S1P has an Rf of 0.5, and the radio-purity was determined to be 95%. This Rf matches the known literature value for this solvent system (Maceyka et al., 2007), as well as the value for cold S1P (visualized by potassium permanganate staining).

2.3 Binding Assay

The binding affinity of S1P ligands was measured by [32P]S1P competitive ligand binding assay. The assay buffer consists of 50 mM HEPES-Na (pH 7.5), 5 mM MgCl2, and 1 mM CaCl2, 0.5% fatty acid-free bovine serum albumin (BSA). S1PR1-3 membranes were diluted in the assay buffer to yield 1-2 μg/well, a final concentration for 96-well plates, and kept on ice. Test compounds were dissolved in dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO) or methanol at a high concentration (1 - 10 mM). The solutions were then diluted in the assay buffer to yield various final concentrations (100 μM - 0.001 nM). [32P]S1P working solutions were diluted in the assay buffer to obtain a final concentration of 0.1 - 0.2 nM.

Test compounds in the assay buffer (50 μL) were pre-incubated with S1PR1-3 membranes (50 μL) for 30 minutes at room temperature. [32P]S1P working solutions were added to give a final volume of 150 μL, 0.1 - 0.2 nM [32P]S1P and 1-2 μg membrane protein per well. Binding was performed for 60 min at room temperature and terminated by collecting the membranes onto 96-well glass fiber (GF/B) filtration plates (Millipore, Billerica, MA), which had been presoaked with 100 μL assay buffer per well for 60 min. Each filter was washed using 200 μL of the assay buffer five times. The filter bound radioactivity was measured by a Beckman LS 3801 scintillation counter using Cherenkov counting. Specific binding was calculated by subtracting radioactivity that remained in the presence of 1000-fold excess of unlabeled S1P (1 μM).

3. Results and discussion

Radiolabeled [33P]S1P is commercially available, however its cost ($4365 / 3.7 MBq from PerkinElmer) makes it prohibitively expensive for screening potential ligands, especially across multiple receptors. Another disadvantage of [33P] is its low inherent energy emissions which decreases the signal to noise ratio, as well as the fact [33P] requires the more specialized beta-counter to determine radioactivity. Using [32P], we were able to take advantage of the higher energy beta emissions to utilize Cerenkov counting as well as the resulting higher signal to noise ratio.

Procedures for preparation of both [33P]S1P and [32P]S1P from radiolabeled γ-ATP have been published in the literature (Maceyka et al., 2007; Van Brooklyn and Spiegel, 2000), however these procedures require an extensive investment of time and resources to achieve reproducibility in preparation; therefore modifications were made to the standard preparation methods. It was reasoned that utilization of a purified recombinant kinase would allow for more reaction consistency as well as a more specific and tunable protocol. The commercially available recombinant human sphingosine kinase 1 (Kohama et al., 1998) has a reported specific activity of >200 pmol/min/μg, however we desired to optimize the amount of kinase required for the reaction. This would allow us to minimize the amount of kinase used, as well as observe the reaction kinetics. We tested three different amounts of kinase (0.01 μg, 0.10 μg, and 0.38 μg) on a 1.11 MBq scale. With 0.01 μg of the kinase only 16% conversion was observed at one hour, with 19% at two hours and 18% at 16 hours. The higher two amounts (0.10 μg and 0.38 μg) gave similar results with roughly 50% conversion at one hour, a slight increase to 54% at two hours, and no additional conversion at 16 hours. Based upon these results we decided to use 0.10 μg for the 1.11 MBq scale and 1.0 μg for the preparation scale (7.4 – 18.5 MBq).

Once the amount of rhSPHK1 was optimized, we were able to produce the desired [32P]S1P with a radiochemical purity of 94-99% and in radiochemical yields of 36-50%. The process from start to finish can be completed in as little as four hours, including the purification and purity measurement. To date, we have completed the procedure on scales of up to 18.5 MBq. By avoiding the cell lysate (the commonly used kinase source), we were able to develop a reliable, reproducible, and scalable method of preparation for [32P]S1P.

To measure the radioactivity of the product, we utilized Cerenkov counting. To establish a calibration curve, we placed known amounts of [γ-32P]ATP in the counter, and built up the curve displayed in Fig. 1, fitting the points with a linear fit that passes through the origin.

Figure 1.

Radioactivity Calibration Curve

While there have been many methods developed to assay potential S1P ligands, most do not directly measure receptor-compound binding. Since research has primarily been focused on therapeutic outcomes, the vast majority of compounds have been screened only for their EC50 (functional) values. For the development of a PET radiotracer, however, the critical property is binding affinity, usually in the form of an IC50 or Ki value (nM) (Eckelman et al., 2006). The most direct method of measuring the binding affinity is with a competition assay using a radiolabeled S1P. In fact, there has been a demonstrated discontinuity between the trends in the functional (EC50) and binding (IC50 value or Ki value) assays for S1P receptor ligands (Gardner and Strange, 1998; Hale et al., 2004) . A radiotracer can either be an agonist or an antagonist as long as it binds at low nM levels (or better) and has high specificity for the target.

In order to establish a competitive radioactivity protocol for assessing the binding affinity of compounds binding to S1P receptors in our laboratory, we elected to use commercially available cell membranes which overexpress the desired receptor. Although the non-specific binding is lower in the living cell binding assay (Van Brocklyn and Spiegel, 2000), the maintenance of the cell-lines with consistent expression levels of S1PRs may have some challenges, especially for labs that do not specialize in cell biology. On the other hand, commercially available cell membranes provide reliable resources of consistent protein concentrations of S1PRs for the binding assay, which will lead to a better reproducibility for screening compounds.

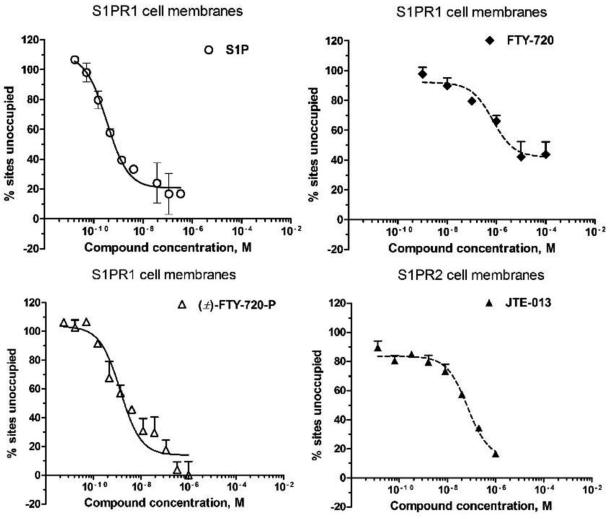

To validate our screening protocol, several known compounds such as S1P, FTY720, (±)-FTY720-P, and JTE-013 were tested. The IC50 values measured by our protocol are shown in Table 1. The binding affinity for these tested compounds are comparable with previous reports (Kiuchi et al., 2005; Mandala et al., 2002; Osada et al., 2002; Satsu et al., 2013). Figure 2 shows representative fitting curves of the competitive binding assay.

Table 1.

IC50 Values of Known Compounds

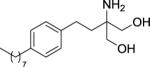

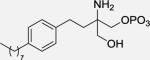

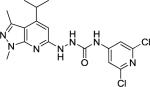

| Compound | Structure | S1PR1 IC50 (nM)a | S1PR2 IC50 (nM)a | S1PR3 IC50 (nM) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SIP |

|

1.00 ± 0.58 (0.47 ± 0.34) | 3.62 ± 0.54 (0.31 ± 0.02) | 0.35 ± 0.16 (0.17 ± 0.05) |

| FTY-720 |

|

603.75 ± 132.02 (300 ± 51) | > 1000 (> 10000) | > 1000 (> 10000) |

| (±) FTY-720-P |

|

2.59 ± 1.74 (4.1 ± 0.63, Ki) | >1000 (> 1000, Ki) | 39.89 ± 18.41 (13 ± 1.6, Ki) |

| JTE-013 |

|

> 1000 (> 10000) | 56.60 ± 16.79 (17 ± 6) | > 1000 (> 10000) |

Each value is an average of two or more runs (means ± standard deviation).

Experimental values in bold, literature values displayed in parentheses

Figure 2.

Representative fitting curve of the competitive binding assay.’ % sites unoccupied’ indicated the percentage of the binding sites which binds with the radioligand, but not the test compound.

4. Conclusion

In summary, we report an easily achievable protocol for the preparation of [32P]S1P that relies upon commercially available recombinant kinase to catalyze ligand phosphorylation. We also report a simple competitive binding assay for screening potential ligands of the S1P receptors, which reduces the time required and has very good reproducibility. These improvements help to streamline the preparation and assay of compounds by increasing screening consistency in addition to simplifying PET ligand development so any laboratory can implement this facile procedure.

Highlights.

Streamlined [32P]S1P production process with reproducible radiochemical yield

Simplified assay of binding affinity for S1P receptors using [32P]S1P

Reliable and repeatable IC50 values can be obtained by the reported method

Acknowledgement

The authors wish to thank Ms. Lynne Jones for her helpful discussions and review of this manuscript. This research was supported by the Department of Energy under grant number DESC0008432, the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS, No. R01NS075527), National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) of the National Institutes of Health (No. MH092797).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting galley proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Briard E, Orain D, Beerli C, Billich A, Streiff M, Bigaud M, Auberson YP. BZM055, an iodinated radiotracer candidate for PET and SPECT imaging of myelin and FTY720 brain distribution. ChemMedChem. 2011;6:667–677. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.201000477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eckelman WC, Kilbourn MR, Mathis CA. Discussion of targeting proteins in vivo: in vitro guidelines. Nucl Med Biol. 2006;33:449–451. doi: 10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2006.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ettmayer P, Billich A, Baumruker T, Mechtcheriakova D, Schmid H, Nussbaumer P. Fluorescence-labeled sphingosines as substrates of sphingosine kinases 1 and 2. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2004;14:1555–1558. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2003.12.099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner B, Strange PG. Agonist action at D2(long) dopamine receptors: ligand binding and functional assays. Br J Pharmacol. 1998;124:978–984. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0701926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hakogi T, Shigenari T, Katsumura S, Sano T, Kohno T, Igarashi Y. Synthesis of fluorescence-Labeled sphingosine and sphingosine 1-phosphate; effective tools for sphingosine and sphingosine 1-phosphate behavior. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2003;13:661–664. doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(02)00999-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hale JJ, Lynch CL, Neway W, Mills SG, Hajdu R, Keohane CA, Rosenbach MJ, Milligan JA, Shei G-J, Parent SA, Chrebet G, Bergstrom J, Card D, Ferrer M, Hodder P, Strulovici B, Rosen H, Mandala S. A rational utilization of high-throughput screening affords selective, orally bioavailable 1-benzyl-3-carboxyazetidine sphingosine-1-phosphate-1 receptor agonists. J Med Chem. 2004;47:6662–6665. doi: 10.1021/jm0492507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inglese M, Petracca M. Imaging multiple sclerosis and other neurodegenerative diseases. Prion. 2013;7:47–54. doi: 10.4161/pri.22650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keul P, Tolle M, Lucke S, von Wnuck Lipinski K, Heusch G, Schuchardt M, van der Giet M, Levkau B. The sphingosine-1-phosphate analogue FTY720 reduces atherosclerosis in apolipoprotein E-deficient mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2007;27:607–613. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000254679.42583.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiferle L, Politis M, Muraro PA, Piccini P. Positron emission tomography imaging in multiple sclerosis–current status and future applications. Eur. J. Neurology. 2011;18:226–231. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2010.03154.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kipp M, Amor S. FTY720 on the way from the base camp to the summit of the mountain: relevance for remyelination. Multiple Sclerosis Journal. 2012;18:258–263. doi: 10.1177/1352458512438723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiuchi M, Adachi K, Tomatsu A, Chino M, Takeda S, Tanaka Y, Maeda Y, Sato N, Mitsutomi N, Sugahara K, Chiba K. Asymmetric synthesis and biological evaluation of the enantiomeric isomers of the immunosuppressive FTY720-phosphate. Bioorg Med Chem. 2005;13:425–432. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2004.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohama T, Olivera A, Edsall L, Nagiec MM, Dickson R, Spiegel S. Molecular cloning and functional characterization of murine sphingosine kinase. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:23722–23728. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.37.23722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunkel GT, Maceyka M, Milstien S, Spiegel S. Targeting the sphingosine-1-phosphate axis in cancer, inflammation and beyond. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2013;12:688–702. doi: 10.1038/nrd4099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maceyka M, Milstien S, Spiegel S. Brown HA, editor. Measurement of Mammalian Sphingosine-1-Phosphate Phosphohydrolase Activity In Vitro and In Vivo. Methods Enzymol. Academic Press. 2007:243–256. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(07)34013-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandala S, Hajdu R, Bergstrom J, Quackenbush E, Xie J, Milligan J, Thornton R, Shei GJ, Card D, Keohane C, Rosenbach M, Hale J, Lynch CL, Rupprecht K, Parsons W, Rosen H. Alteration of lymphocyte trafficking by sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor agonists. Science. 2002;296:346–349. doi: 10.1126/science.1070238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller DH, Altmann DR, Chard DT. Advances in imaging to support the development of novel therapies for multiple sclerosis. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2012;91:621–634. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2011.349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Sullivan C, Dev KK. The structure and function of the S1P1 receptor. Trends in Pharmacological Sciences. 2013;34:401–412. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2013.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osada M, Yatomi Y, Ohmori T, Ikeda H, Ozaki Y. Enhancement of sphingosine 1-phosphate-induced migration of vascular endothelial cells and smooth muscle cells by an EDG-5 antagonist. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2002;299:483–487. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(02)02671-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prasad VP, Wagner S, Keul P, Hermann S, Levkau B, Schäfers M, Haufe G. Synthesis of fluorinated analogues of sphingosine-1-phosphate antagonists as potential radiotracers for molecular imaging using positron emission tomography. Bioorg Med Chem. 2014;22:5168–5181. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2014.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosen H, Germana Sanna M, Gonzalez-Cabrera PJ, Roberts E. The organization of the sphingosine 1-phosphate signaling system. In: Oldstone MBA, Rosen H, editors. Sphingosine-1-Phosphate Signaling in Immunology and Infectious Diseases. Springer International Publishing; 2014. pp. 1–21. 2014/04/15. [Google Scholar]

- Sanna MG, Wang S-K, Gonzalez-Cabrera PJ, Don A, Marsolais D, Matheu MP, Wei SH, Parker I, Jo E, Cheng W-C, Cahalan MD, Wong C-H, Rosen H. Enhancement of capillary leakage and restoration of lymphocyte egress by a chiral S1P1 antagonist in vivo. Nat Chem Biol. 2006;2:434–441. doi: 10.1038/nchembio804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satsu H, Schaeffer MT, Guerrero M, Saldana A, Eberhart C, Hodder P, Cayanan C, Schurer S, Bhhatarai B, Roberts E, Rosen H, Brown SJ. A sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor 2 selective allosteric agonist. Bioorg Med Chem. 2013;21:5373–5382. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2013.06.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimizu T, De Wispelaere A, Winkler M, D'Souza T, Caylor J, Chen L, Dastvan F, Deou J, Cho A, Larena-Avellaneda A, Reidy M, Daum G. Sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor 3 promotes neointimal hyperplasia in mouse iliac-femoral arteries. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2012;32:955–961. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.111.241034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soliven B, Miron V, Chun J. The neurobiology of sphingosine 1-phosphate signaling and sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor modulators. Neurology. 2011;76:S9–14. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31820d9507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swan DJ, Kirby JA, Ali S. Vascular biology: the role of sphingosine 1-phosphate in both the resting state and inflammation. J Cell Mol Med. 2010;14:2211–2222. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2010.01136.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urbano M, Guerrero M, Rosen H, Roberts E. Modulators of the Sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor 1. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2013;23:6377–6389. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2013.09.058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Brocklyn JR, Spiegel S. Binding of sphingosine 1-phosphate to cell surface receptors. Methods Enzymol. 2000;312:401–406. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(00)12925-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Brooklyn JR, Spiegel S. Alfred HM, Yusuf AH, editors. [32] - Binding of Sphingosine 1-Phosphate to Cell Surface Receptors. Methods Enzymol. Academic Press. 2000:401–406. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(00)12925-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Doorn R, Van Horssen J, Verzijl D, Witte M, Ronken E, Van Het Hof B, Lakeman K, Dijkstra CD, Van Der Valk P, Reijerkerk A, Alewijnse AE, Peters SL, De Vries HE. Sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor 1 and 3 are upregulated in multiple sclerosis lesions. Glia. 2010;58:1465–1476. doi: 10.1002/glia.21021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto T, Hasegawa H, Hakogi T, Katsumura S. Syntheses of Fluorescence-labeled Sphingosine 1-Phosphate Methylene and Sulfur Analogues as Possible Visible Ligands to the Receptor. Chem. Lett. 2008;37:188–189. [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida Y, Nakada M, Sugimoto N, Harada T, Hayashi Y, Kita D, Uchiyama N, Yachie A, Takuwa Y, Hamada J. Sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor type 1 regulates glioma cell proliferation and correlates with patient survival. Int J Cancer. 2010;126:2341–2352. doi: 10.1002/ijc.24933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]