Abstract

Diet-induced obesity can increase the risk for developing age-related neurodegenerative diseases including Parkinson’s disease (PD). Increasing evidence suggests that mitochondrial and proteasomal mechanisms are involved in both insulin resistance and PD. The goal of this study was to determine whether diet intervention could influence mitochondrial or proteasomal protein expression and vulnerability to 6-Hydroxydopamine (6-OHDA)-induced nigrostriatal dopamine (DA) depletion in rats’ nigrostriatal system. After a 3 month high-fat diet regimen, we switched one group of rats to a low-fat diet for 3 months (HF-LF group), while the other half continued with the high-fat diet (HF group). A chow group was included as a control. Three weeks after unilateral 6-OHDA lesions, HF rats had higher fasting insulin levels and higher Homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance (HOMA-IR), indicating insulin resistance. HOMA-IR was significantly lower in HF-LF rats than HF rats, indicating that insulin resistance was reversed by switching to a low-fat diet. Compared to the Chow group, the HF group exhibited significantly greater DA depletion in the substantia nigra but not in the striatum. DA depletion did not differ between the HF-LF and HF group. Proteins related to mitochondrial function (such as AMPK, PGC-1α), and to proteasomal function (such as TCF11/Nrf1) were influenced by diet intervention, or by 6-OHDA lesion. Our findings suggest that switching to a low-fat diet reverses the effects of a high-fat diet on systemic insulin resistance, and mitochondrial and proteasomal function in the striatum. Conversely, they suggest that the effects of the high-fat diet on nigrostriatal vulnerability to 6-OHDA-induced DA depletion persist.

Keywords: OBESITY, DOPAMINE, 6-HYDROXYDOPAMINE

1. Introduction

Numerous studies indicate links between obesity, type 2 diabetes, and age-related neurodegenerative diseases such as Parkinson’s disease (PD) (Hu et al., 2007, Aviles-Olmos et al., 2013). Recent studies from our lab and others demonstrate that a high-fat diet increases dopamine (DA) depletion in the 6-hydroxydopamine (6-OHDA) rat and in the MPTP mouse models of PD (Choi et al., 2005, Morris et al., 2010). These effects resemble the effect of aging of the nigrostriatal pathway, which is the leading contributor to PD. They also suggest that switching to a low-fat diet should decrease neuronal vulnerability. Despite this prediction, little is known about the long-term effects of diet-induced obesity on neuronal vulnerability to PD. Recent findings indicate that a high-fat diet can produce permanent effects on the brain (Thaler et al., 2012, Naef et al., 2013). It is possible that the effects of a high-fat diet on nigrostriatal vulnerability persist even after a switch to a healthier, low-fat diet. The answer to this question is important because it has implications for interventions to prevent Parkinsonism in this population.

Converging evidence suggests that mitochondrial mechanisms are involved in both insulin resistance and neurodegeneration (Aviles-Olmos et al., 2013). Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ coactivator 1α (PGC-1α), an important regulator of enzymes related to mitochondrial respiration, is associated with type 2 diabetes (Bhat et al., 2007), and has been implicated as playing a critical role in the pathogenesis of PD (Aviles-Olmos et al., 2013). Conversely, abrogation of the ubiquitin-proteasome system is also considered to play a role in the progression of both diseases (Santiago and Potashkin, 2013). It is likely that disruption of multiple pathways puts type 2 diabetic patients at higher risk of PD.

The purpose of this study was to test whether switching to a low-fat diet could reduce the 6-OHDA-induced nigrostriatal DA depletion in rats fed a high-fat diet for 3 months. In addition, we wanted to measure proteins related to mitochondrial (such as AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK), PGC-1α) and proteasomal (such as Transcription factor 11/Nuclear factor E2-related factor 1(TCF11/Nrf1)) function in striatal tissue in order to determine the extent to which these pathways are affected by diet intervention.

2. Results

2.1 Effects of feeding on body weight and glucose metabolism

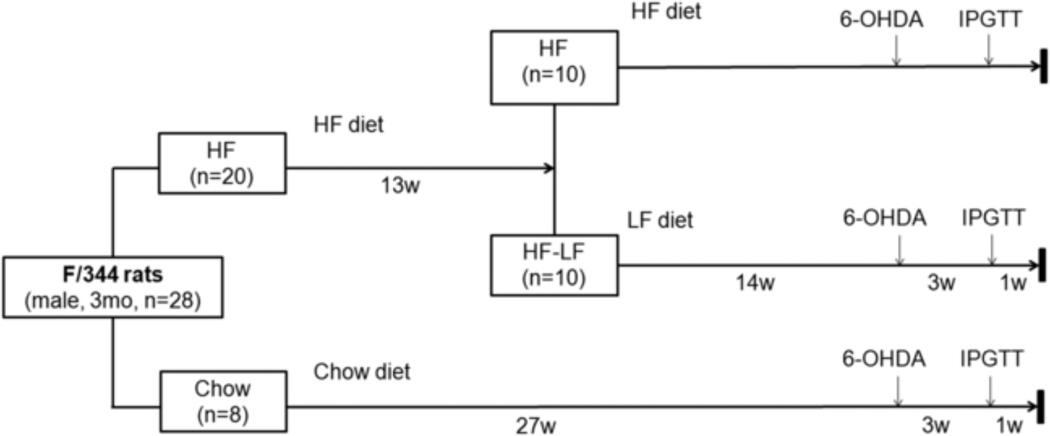

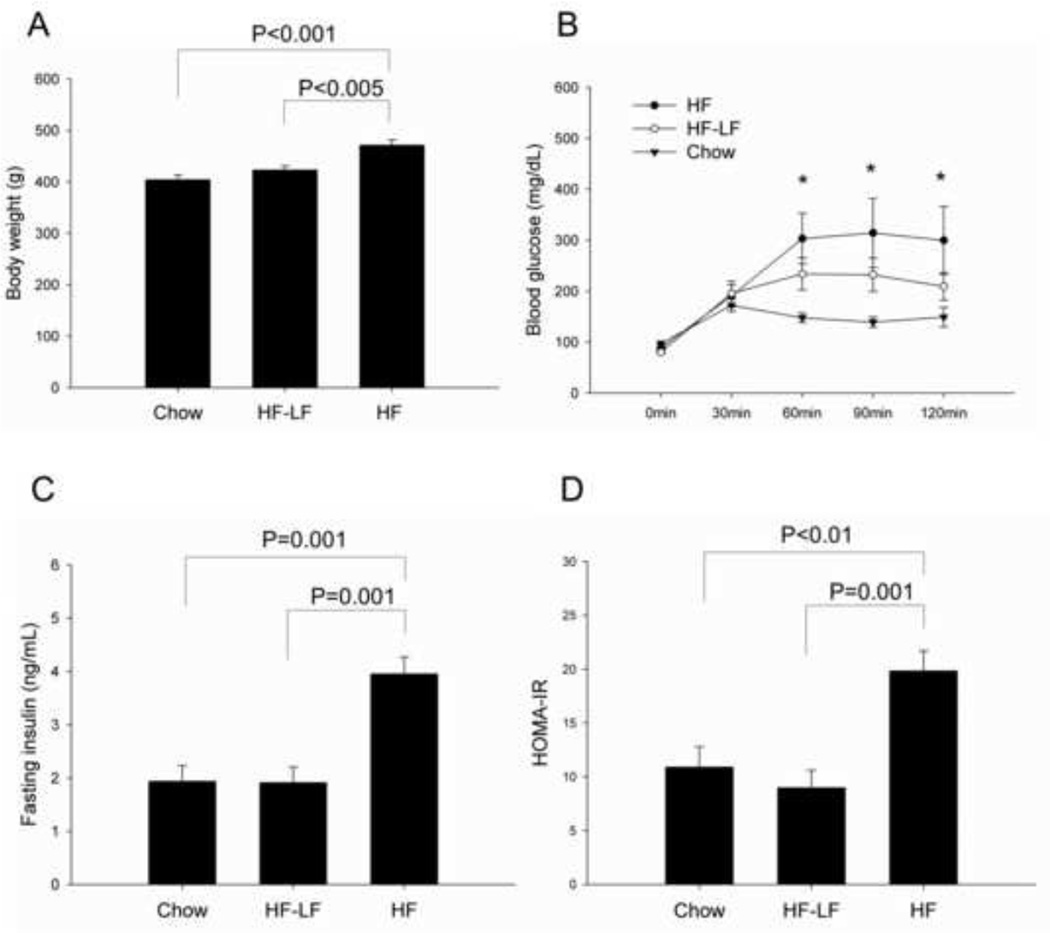

Three-month-old Fischer 344 rats were randomly divided into a high-fat (HF) group, a high-fat to low-fat (HF-LF) group, and a Chow group. Rats in the HF group (n=10) received a high fat diet comprised of 60% calories from fat. Rats in the HF-LF group (n=10) received high fat diet (60% calories from fat) for 13 weeks, and then were switched to a low-fat (10% calories from fat) chow. Rats in the Chow group (n=8) received standard chow (14% calories from fat) throughout the study. Four weeks before the end of the study, a unilateral 6-OHDA lesion was performed in the medial forebrain bundle of all animals (Fig 1). After 6 months’ feeding of high-fat diet, the HF group had significantly higher body weight than the Chow group (P< 0.001). Body weight gain in the HF-LF group slowed after switching to LF diet. After 3 months feeding on the LF diet, body weights for the HF-LF group were significant lower than the HF group (P < 0.005), and did not differ significantly from the Chow group (Fig 2A).

Fig 1.

Study design.

Fig 2.

Body weight and glucose metabolism. (A) HF group had significantly higher body weight than both Chow and HF-LF group by the end of study. (B) Intraperitoneal glucose tolerance test (IPGTT) was performed 1 week before tissue harvest. Blood glucose was measured in tail blood at 5 time points: 0, 30, 60, 90, and 120 min after glucose injection (injection at 0min). The HF group exhibited significantly higher glucose values than the Chow group at 60, 90, and 120 min. (C) The HF group had a significantly higher fasting plasma insulin and (D) higher HOMA-IR than Chow or HF-LF group. Values are expressed as mean ± S.E. for 6–8 rats per group. *P < 0.05 HF vs. Chow.

An intraperitoneal glucose tolerance test (IPGTT) was performed on all rats 1 week before tissue harvest. Comparison of glucose levels between HF and Chow group revealed a significant main effect of time (P< 0.001), and a significant interaction effect between group and time (P < 0.01). Glucose comparison between HF-LF and Chow groups also revealed a significant main effect of time (P< 0.001), and a significant interaction effect between group and time (P < 0.01) (Fig 2B). There were no significant differences in fasting glucose between the three groups, and they all had increased glucose levels in response to glucose bolus. However, the Chow group reached peak glucose values around 30min, while the HF group reached peak values around 60min, and had significantly higher glucose levels than the Chow group rats at subsequent time points. The HF-LF group had lower glucose levels than HF group, but was still higher than Chow group during the period of 60–120min. Fasting plasma insulin in the HF group was significantly higher than the Chow (P= 0.001) or HF-LF groups (P=0.001) (Fig 2C). Similarly, Homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance (HOMA-IR) also showed significantly higher values in HF group than both the Chow group (P < 0.01) and the HF-LF group (P= 0.001) (Fig 2D). There were no differences between the three groups with regard to insulin levels after glucose injection, so data are not shown.

2.2 Rotation behavior

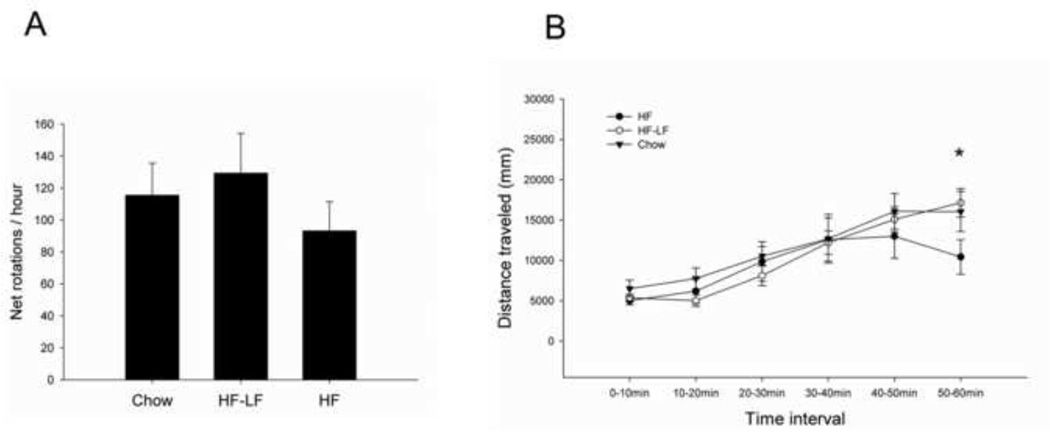

Rotational behavior evoked by amphetamine was assessed two weeks after the 6-OHDA lesion, and comparison between the three groups did not reveal significant differences in either net rotations (Fig 3A), or in total distance traveled during the 1 hour session. However, if we looked into the distance traveled within every 10 min time interval, the comparison between the three groups yielded a significant main effect for time (P< 0.001), and significant interaction effect of time and group (P < 0.05) (Fig 3B). The distance traveled by all three groups gradually increased with time, but slightly decreased in the HF group by the end of the session. Comparison between the three groups of distance traveled during 50–60min revealed a significant difference between the HF and HF-LF group (P < 0.05), and a trend for a difference between the HF and Chow group (P= 0.084).

Fig 3.

Amphetamine-elicited rotational behavior. (A) Comparison between the three diet groups did not reveal significant differences in net rotations. (B) When the distance traveled was quantified across 10 min time bins during rotation sessions, a significant effect of time (P< 0.001), and a significant interaction between time and group (P < 0.05) were revealed. Values are expressed as mean ± S.E. for 6–8 rats per group. * P < 0.05 HF vs. HF-LF in distance traveled during 50–60min.

2.3 DA depletion and DA turnover

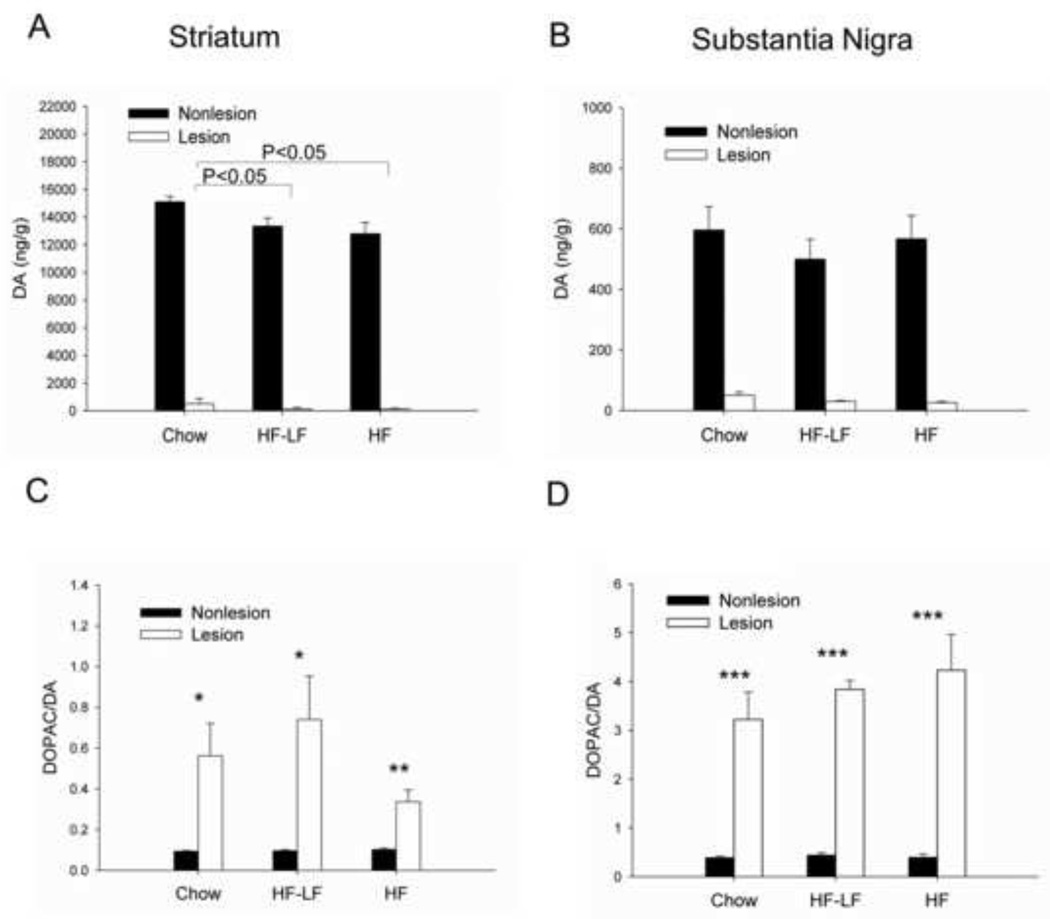

DA and 3,4-dihydroxyphenylacetic acid (DOPAC) levels in the striatum and SN were measured in all rats. Striatal DA depletion ranged from 17–99%. Striatal DA depletion did not differ between the Chow (96.8% ± 2.4%), HF-LF (98.9% ± 0.9%), and HF groups (99.0% ± 0.35%). However, striatal DA content in the Chow group was significantly greater than the HF group (P < 0.05) and HF-LF group (P < 0.05), which led to a significant group effect (P=0.037), but no significant interaction between group and hemisphere (Fig 4A). SN DA depletion in the HF group (95.0% ± 0.7%) was significantly greater than in the Chow group (91.9% ± 0.67%) (P < 0.05), but did not differ from HF-LF group (93.5% ± 1.0%) (Fig 4B).

Fig 4.

Dopamine (DA) content and DA turnover in striatum (A, C) and SN (B, D). Striatal DA content in the Chow group was significantly greater than the HF group and HF-LF group. DA depletion in SN of the HF group was significantly higher than the Chow group, but was similar to HF-LF group. For all three diet groups, DA turnover was significantly increased in the lesioned hemisphere compared with the non-lesioned hemisphere in both striatum and SN. Values are expressed as mean ± S.E. for 6–8 rats per group. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P ≤ 0.001 lesioned vs. non-lesioned hemisphere.

To determine whether diet intervention affected DA metabolism, the ratio of DOPAC to DA (a measure of DA turnover) was analyzed. In both striatum and SN, there was a significant effect for hemisphere (P<0.001), as DOPAC/DA was significantly increased in the lesioned hemisphere compared to the the non-lesioned hemisphere in all three groups. However, there was no significant effect for group, nor was there a significant interaction between group and hemisphere in either striatum or SN (Fig 4C, 4D).

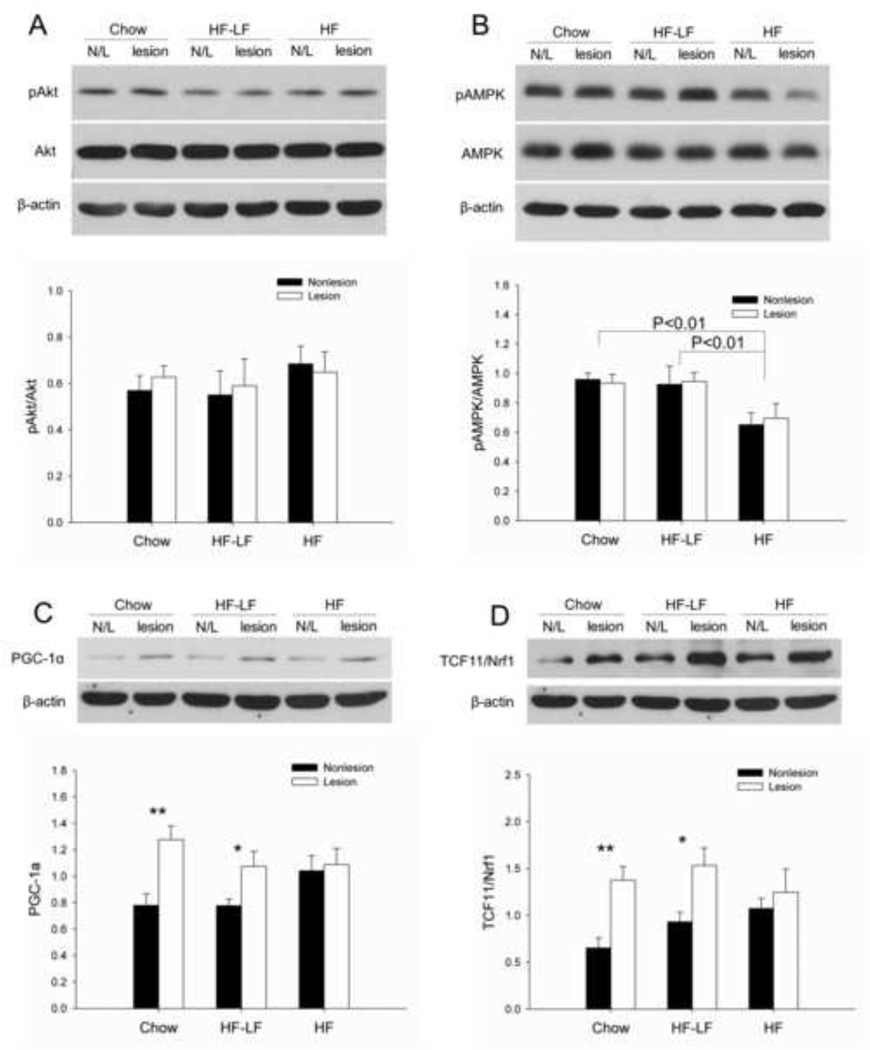

2.4 Protein effects in striatum

In order to explore the pathways involved in insulin resistance and 6-OHDA lesions, we measured the activation of Akt and AMPK, and protein levels of PGC-1α and TCF11/Nrf1 in striatum of both lesioned and non-lesioned hemispheres. Both Akt and AMPK are activated by phosphorylation, thus phospho-Akt (pAkt) and phospho-AMPK (pAMPK) were measured and normalized by total Akt or total AMPK. There were no significant effects for group or hemisphere with regard to pAkt/Akt (Fig 5A). Phosphorylation of AMPK was significantly lower in the HF group than both the Chow (P < 0.01) and HF-LF groups (P < 0.01), but was not influenced by hemisphere (Fig 5B). PGC-1α and TCF11/Nrf1 were both significantly increased in the lesioned hemisphere compared to the non-lesioned hemisphere in the Chow group and HF-LF group, but not in the HF group. This led to a significant main effect for hemisphere (P < 0.005), and a trend for an interaction between group and hemisphere (P=0.103), but no significant effect for group with regard to PGC-1α levels (Fig 5C). Similarly, for TCF11/Nrf1, there was a significant main effect for hemisphere (P<0.001), and a significant interaction between group and hemisphere (P < 0.05), but no significant effect for group (Fig 5D).

Fig 5.

Protein expression in rat striatum. (A) There were no between-groups or between-hemisphere differences in pAkt/Akt. (B) Activation of AMPK (shown as pAMPK/AMPK) was significantly lower in the HF group than both the Chow (P<0.01) and HF-LF group (P<0.01), but did not differ between hemispheres. (C) PGC-1α levels were significantly higher on the lesion side compared to the non-lesioned side in the Chow and HF-LF group, but were similar between the two hemispheres in HF group. (D) Similarly, TCF11/Nrf1 levels were significantly higher on the lesion side compared to the non-lesioned side in the Chow and HF-LF group, but not in HF group. There was a significant interaction between group and hemisphere (P < 0.05) for TCF11/Nrf1. Values are expressed as mean ± S.E. for 6 rats per group. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 lesioned vs. non-lesioned hemisphere.

3. Discussion

The major findings of the current study are that after switching to a low-fat diet, insulin sensitivity was significantly improved in high fat-fed rats, but not their neuronal vulnerability to 6-OHDA. We also found evidence that a high-fat diet influences mitochondrial- and proteasomal-related proteins in striatum, and that switching to a low-fat diet may increase protective mitochondrial and proteasomal pathways in response to 6-OHDA. However, this protection was not sufficient to abrogate the effects of 6-OHDA.

A positive relationship between the level of fat in the diet and body weight in rats has long been reported, and it has also been reported that a switch to low-fat diets can induce weight loss in rats with diet-induced obesity (Bartness et al., 1992, Hariri and Thibault, 2010). Our previous studies have used Fischer 344 rats fed a high-fat diet to model diet-induced obesity with insulin resistance (Morris et al., 2010), and reported that HF feeding can impair glucose tolerance (Gupte et al., 2009). In the current study, we found a reduction in body weight when adult male Fischer 344 rats fed a high-fat diet for 13 weeks were switched to low-fat diet. We also found that insulin sensitivity was normalized after a switch to a low-fat diet. Using HOMA-IR, we found that insulin sensitivity was greater in both the Chow and HF-LF groups than in the HF group. This indicates that while long term HF feeding can induce insulin resistance, switching back to LF diet can reverse this effect, restoring insulin sensitivity in HF fed rats to levels similar to control rats. However, fasting glucose levels were not different between the various diets. A possible explanation for this is that the HF fed rats were only at prediabetic stage by the end of the current study. This stage is characterized by insulin resistance and glucose intolerance, but not necessarily impaired fasting glucose. Meanwhile, although insulin sensitivity was restored in HF fed rats after switching to LF diet, we did not observe a significant improvement in glucose tolerance. This finding suggests that three months of HF feeding irreversibly impaired glucose tolerance. The IPGTTs were performed under anesthesia, and it is possible anesthesia influenced glucose metabolism to some degree. However, pentobarbital influences glucose metabolism less than most other anesthetics (Zuurbier et al., 2008). Furthermore, all rats received the same dose of pentobarbital based on their body weight, so the insulin and glucose measurements were made under the same conditions for the three diet groups.

Rotation behavior evoked by amphetamine in rats with unilateral 6-OHDA lesions is believed to be related to the degree of dopamine receptor stimulation in the non-lesioned versus the lesioned hemisphere (Ungerstedt and Arbuthnott, 1970). In this study, rotational behavior was successfully evoked by amphetamine for all experimental rats, indicating unilateral nigrostriatal DA depletion. Similar to our previous studies (Morris et al., 2010), we did not measure significant differences in net rotations between HF and Chow rats. This result was may have been due a lack of diet effect on dopamine receptor stimulation, or that the HF feeding did not influence DA levels greatly enough to lead to behavioral differences. We did measure less activity in the HF group compared to the other two groups by the end of the rotation session, however. It is possible that the differences we observed in the non-lesioned hemispheres between the diet groups accounted for this effect. More sensitive behavioral tests that can measure unilateral motor function (Bethel-Brown et al., 2011) are necessary to test this hypothesis. Another possible explanation is that the insulin resistance in HF rats may have led to greater fatigue in this group after continuous activity. Clearly, further studies are needed to address this effect.

Increasing evidence links impaired glucose tolerance to PD (Hu et al., 2007, Aviles-Olmos et al., 2013). Between 50–80% of patients with PD have abnormal glucose tolerance (Aviles-Olmos et al., 2013). We reported in our previous study that impaired glucose tolerance following a HF diet in middle-aged rats results in significantly greater nigrostriatal DA depletion than chow-fed rats after 6-OHDA treatment (Morris et al., 2010). The fact that striatal DA depletion did not differ significantly between the diet groups may be due to the more severe depletions we achieved in this study. Although it seems counterintuitive, the younger and smaller rats we used in the current study may account for the more severe striatal DA depletions. Stereotaxic coordinates for both studies were based on an atlas that used young adult rats (Paxinos and Watson, 1998). Even minimal differences in animals’ sizes may have influenced targeting of the medial forebrain bundle. In contrast, we did find that in the SN, the rats in the HF group exhibited significantly greater DA depletion than Chow group rats. Switching to LF diet did not reverse this effect. In addition, we found lower DA content in striatum of HF and HF-LF rats compared to controls, which suggests that changes in DA content following a high fat diet may not be affected by diet management. Nevertheless, it is possible that the lack of diet effect on DA lesion severity may be due to the extent of the lesions, and that the diet manipulation may have had a protective effect following a less severe lesion.

The ratio of DOPAC to DA in tissue, believed to reflect DA turnover or metabolism, is responsive to changes in nigrostriatal DA content. It was reported that unilateral destruction of the nigrostriatal dopamine pathway can lead to significant increases in DA turnover in the lesioned compared to the non-lesioned hemisphere (Altar et al., 1987). In our previous study, we found that DA depletion only increased DA turnover in SN of HF group (Morris et al., 2010), with the measure not differing between groups or hemispheres in the striatum. In the current study, DA turnover was significantly elevated in both the SN and striatum of the lesioned hemisphere for all diet groups. Given depletion differences between our current and former studies, a severe DA depletion may be required to increase DA turnover in both SN and striatum.

Impaired brain insulin signaling has been considered as a potential mechanism by which type 2 diabetes increases the risk for neurodegenerative disease, such as Alzheimer’s disease (Yang et al., 2013). Akt plays an important role in insulin signaling, and is activated by dual phosphorylation on threonine 308 and serine 473 (Lawlor and Alessi, 2001). Insulin can activate the PI3K/Akt pathway, which triggers cellular glucose uptake in peripheral insulin-sensitive tissues and in some regions of the brain (Yamamoto et al., 2012). It was reported that levels of phosphorylated Akt were significantly lower in the hippocampus of rat and mouse models of type 2 diabetes (Yamamoto et al., 2012, Zhao et al., 2012, Yang et al., 2013). In contrast, there was a study reporting greater Akt phosphorylation in both cerebral cortex and hippocampus of db/db mice (a type 2 diabetes mouse model) (Clodfelder-Miller et al., 2005). In the current study, we found that the phosphorylated level of Akt in rat striatum was not significantly influenced by either long-term high-fat diet or by 6-OHDA, which suggests that insulin signaling mediated by Akt might not be a critical link between insulin resistance and Parkinson’s disease.

Increasing evidence suggests that mitochondrial mechanisms are involved in both insulin resistance and neurodegeneration (Aviles-Olmos et al., 2013). AMPK is a critical regulator of mitochondrial biogenesis in response to energy deprivation (Canto et al., 2009). A substantial body of literature indicates that AMPK is a neuroprotective factor (Salminen et al., 2011). It was reported that AMPK activation is increased in the substantia nigra of MPTP-intoxicated mice, and that AMPK activation may increase cell survival in PD (Choi et al., 2010). Another study reported that hippocampal levels of total and phosphorylated AMPK were reduced after high fat consumption (Wu et al., 2006). In our study, we found that a high-fat diet greatly reduced the activation of AMPK (shown as pAMPK/AMPK) in rat striatum, while switching to LF diet can restore AMPK activation. Considering that high fat-fed rats had lower DA levels than control rats, we speculate that high fat diet-induced deficiencies in AMPK activation exerted a detrimental effect on DA neuronal function. However, unlike the previous study in MPTP mice (Choi et al., 2010), we did not measure a significant influence of 6-OHDA lesion on AMPK activation, which suggests that AMPK and DA depletion may be unrelated.

PGC-1α is an important regulator of enzymes involved in both mitochondrial function and insulin resistance, and is potentially pivotal in the pathogenesis of PD (Aviles-Olmos et al., 2013). PGC-1α is expressed in the liver, muscle, and brain. Its expression is downregulated in skeletal muscles of insulin resistant and T2D subjects (Canto and Auwerx, 2009), but upregulated in liver tissue from diabetic mice (Puigserver et al., 2003, Koo et al., 2004). Increasing PGC-1α levels protects neural cells in culture from oxidative stress (St-Pierre et al., 2006), and over-expression of PGC-1α protects against DA cell loss induced by rotenone (Zheng et al., 2010). To our knowledge, there is no study detecting the expression of PGC-1α in striatum of insulin resistant rat model. In the current study, the high-fat diet significantly increased PGC-1α expression in non-lesioned striatal tissue, while switching to LF diet from high-fat diet reversed this effect. Meanwhile, striatal PGC-1α level was significantly higher in the 6-OHDA lesion side than in the non-lesioned side in the Chow and HF-LF group, but was similar between the two hemispheres in HF group. We speculate that long-term high-fat diet induces brain insulin resistance in rat, which inhibits AMPK activation in the nigrostriatal pathway, and induces DA dysfunction. In response to this detrimental effect of a high fat diet, PGC-1α expression is elevated to protect neurons. PGC-1α expression is also elevated in response to 6-OHDA lesion, but this effect is relatively insensitive in HF group rats, probably because PGC-1α levels are maximal.

The ubiquitin proteasome system (UPS) is a fundamental mechanism for degrading oxidant-damaged proteins, while proteasomal dysfunction is associated with a variety of human disorders, including diabetes and PD (Costes et al., 2011, Koch et al., 2011, Geisler et al., 2014). TCF11 (long isoform of Nrf1) is a key regulator for proteasome formation, and was recently discovered to transcriptionally control proteasomal degradation via an endoplasmic reticulum-associated protein degradation (ERAD)-dependent feedback loop (Steffen et al., 2010). TCF11 can induce the transcription of cytoprotective genes (Myhrstad et al., 2001, Biswas and Chan, 2010), and it was reported that TCF11/Nrf1 overexpression can increase intracellular glutathione, which plays an important protective role against free radical damage in the cell (Myhrstad et al., 2001). However, whether TCF11/Nrf1 plays a role in metabolic or neurodegenerative disease is still unknown. Interestingly, we found that both high-fat diet and 6-OHDA lesion strongly affected striatal TCF11/Nrf1 levels, suggesting that TCF11/Nrf1 may also function in a neuroprotective role similar to PGC-1α.

In summary, our findings show key differences between peripheral and central effects of a high fat diet, and suggest that the neuronal effects of a high-fat diet might persist after a switch to a low-fat diet. In addition, to our knowledge, we are the first to measure the levels of PGC-1α and TCF11/Nrf1 in striatum of a PD rat model combined with insulin resistance. Our results support that mitochondrial and proteasomal pathways may be involved in both insulin resistance and PD, and suggest that both PGC-1α and TCF11/Nrf1 are promising targets for reducing the risk of both diseases.

4. Experimental procedures

4.1 Animals and diet

Three-month-old Fischer 344 rats were obtained from National Institutes on Aging colonies (Harlan). Rats were individually housed on a 12:12 h light/dark cycle, and provided food and water ad libitum. Rats in the high-fat (HF) group (n=10) received a diet comprised of 60% calories from fat (D12492; Research Diets, New Brunswick, NJ). Rats in the high-fat to low-fat (HF-LF) group (n=10) received high-fat diet for 13 weeks, and then were switched to a low-fat chow (D12450J, 10% calories from fat, Research Diets) until the end of the study. Rats in the Chow group (n=8) received a standard chow diet (Harlan Teklad rodent diet 8604; 14% calories from fat) throughout the study. Protocols for animal use were approved by the University of Kansas Medical Center Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and adhered to the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (National Research Council, 1996).

4.2 Materials

Chemicals used in high pressure liquid chromatography (HPLC) and D-(+)-glucose were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St.Louis, MO). Rat insulin ELISA kits were purchased from Alpco Diagnostics (Salem, NH). Antibodies used include actin (Abcam, Cambridge, MA); phospho-Akt (S473), total Akt, phospho-AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) (T172), total AMPK, and Transcription factor 11/Nuclear factor E2-related factor 1 (TCF11/Nrf1) (Cell Signaling, Beverly, MA); peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ coactivator 1α (PGC-1α; Calbiochem, San Diego, CA).

4.3 6-OHDA infusion

Unilateral 6-OHDA lesion was performed in the medial forebrain bundle of all animals, based on our previously published study (Morris et al., 2008). Anesthesia was induced with 5% isoflurane, rats were placed in a stereotaxic frame, and anesthesia was maintained with 3% isoflurane during surgery. Rats were infused with 3 µg 6-OHDA (4 µl of 0.75 mg/ml 6-OHDA in 0.9% NaCl with 0.02% ascorbate) into the right medial forebrain bundle (stereotaxic coordinates with respect to bregma: M/L 1.3mm, A/P - 4.4mm, and D/V - 7.8mm). The infusion rate was 0.5 µl/min, and the cannula was withdrawn 5 min following infusion. Animals were allowed to recover for 2 week postsurgery. Two weeks after the surgery, animals were intraperitoneally injected with 0.25% amphetamine at the dose of 2.5mg/kg body wt, and immediately placed onto a force plate rotometer in a dark room for 1 hour so that rotation evoked by amphetamine could be measured.

4.4 Glucose tolerance analysis

Three weeks after the surgery, animals were administered an IPGTT, based on previous studies (Morris et al., 2010). Animals were fasted overnight (12 h), and then were anesthetized with sodium pentobarbital (50 mg/kg, i.p.). To begin the test, rats were injected with a 60% D-(+)-glucose (Sigma) solution at 2 g/kg body weight. After injection, blood glucose was measured using a glucometer at 0, 30, 60, 90, and 120 min, and 400 µl of tail blood was collected at each timepoint for measurement of serum insulin. Blood samples were placed on ice for 30 min and centrifuged for 1 h at 3,000 g, and serum was aliquoted and stored in −80°C, and was analyzed later for serum insulin using a rat insulin ELISA (Alpco). HOMA-IR was used in estimating rats’ insulin sensitivity, and it was calculated using this equation: HOMA-IR= Fasting Glucose (mg/dL) × Fasting Insulin (mIU/L)/405 (Matthews et al., 1985). Since international unit has not been established for rat, the insulin units were converted to the human type according to previous study (1 mg = 23.1 IU) (Takaya et al., 2014).

4.5 Tissue harvest

At 4 weeks post-lesion, animals were deeply anesthetized and decapitated for tissue harvest. Brains were then removed and immediately placed on an ice cold brain block. Samples of striatum and substantia nigra (SN) from each hemisphere were carefully dissected, weighed, and frozen on dry ice, and stored into −80°C for HPLC-EC and Western blotting analysis.

4.6 HPLC-Electrochemical detection (HPLC-EC)

HPLC-EC measurements were used to detect DA and 3,4-dihydroxyphenylacetic acid (DOPAC) levels in the striatum and SN. Each striatal sample was processed through sonication in 450 µl of burnt, filtered citrate acetate mobile phase with 50 µl 3,4-dihydroxybenzylamine (DHBA) (1e-6M), while each SN sample was processed in 450 µl of burnt mobile phase and 50 µl DHBA (1e-7M). Samples were prepared and analyzed by HPLC, as described previously (Morris et al., 2008). DA depletion values for each rat were calculated using the equation: percentage DA depletion = (1-DAlesioned/ DAnon-lesioned) × 100. Due to a somewhat bimodal distribution (i.e. 6 rats exhibited partial DA depletion between 17–70%, while 21 exhibited severe DA depletion 85–99%), the partially-depleted rats (plus an additional rat that died during the experiment) were excluded from all the analysis of this study.

4.7 Western immunoblotting

Frozen striatal samples were briefly sonicated in 15× volume of cell extraction buffer (Invitrogen) with protease inhibitor cocktail (500 µl, Invitrogen), sodium fluoride (200 mM), sodium orthovanadate (200 mM), and phenylmethanesulfonylfluoride (200 mM) added. Protein extraction was allowed to occur on ice for 1 hour with intermittent vortexing. Tubes were centrifuged at 3,000 g at 4°C for 20 min, and supernatants were collected into fresh tubes. A Bradford assay was performed to determine protein concentration of supernatants. Samples of the same concentration were generated by diluting them with HES buffer (20 mM HEPES, 1 mM EDTA, 250 M sucrose, pH 7.4), and reducing sample buffer (0.3 M Tris-HCL, 5% SDS, 50% glycerol, 100 mM dithiothreitol, Thermo Scientific) based on protein concentration.

Samples were run on 10% SDS-PAGE gels and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes at 200 mA for 90 min. Nonspecific binding sites on the membranes were blocked in 5% milk for 1 h. The membranes were then incubated overnight with primary antibody at 4°C. After washing with TBST, the membranes were incubated with horseradish peroxide-conjugated secondary antibody for 1 h at room temperature. Films were scanned at high resolution, and densitometry measurements were analyzed using Image J software. Protein content was normalized to the loading control β-actin.

4.8 Statistical analyses

Data for IPGTT measurements and distance traveled within each time interval were analyzed using two-way ANOVA with diet as the grouping variable and time as the repeated measure. DA levels, DA turnover, and western blots results were analyzed using two-way ANOVA with hemisphere as a within-subjects variable and diet groups as a between-subjects variable followed by LSD tests. Then within diet groups, differences between hemispheres were further calculated by one-way ANOVA. All the other data was analyzed using one-way ANOVA followed by LSD test. Data were considered statistically significant at P ≤ 0.05.

Highlights.

After switching to a low-fat diet, insulin sensitivity and glucose intolerance were improved in high-fat fed rats.

Switching to a low-fat diet did not ameliorate the neural vulnerability to 6-OHDA in high-fat fed rats

High-fat diet influences mitochondrial- and proteasomal-related proteins in rats’ striatum.

Switching to a low-fat diet may increase protective mitochondrial and proteasomal pathways in response to 6-OHDA

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by The Lied Foundation and The Kansas Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities Research Center (HD02528).

Abbreviations

- PD

Parkinson’s disease

- DA

Dopamine

- 6-OHDA

6-Hydroxydopamine

- PGC-1α

Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ coactivator 1α

- AMPK

AMP-activated protein kinase

- pAMPK

phospho-AMP-activated protein kinase

- TCF11/Nrf1

Transcription factor 11/Nuclear factor E2-related factor 1

- HF

High-fat

- LF

Low-fat

- IPGTT

Intraperitoneal glucose tolerance test

- HOMA-IR

Homeostasis Model Assessment of Insulin Resistance

- HPLC-EC

High Pressure liquid chromatography-Electrochemical detection

- DOPAC

3,4-Dihydroxyphenylacetic acid

- DHBA

3,4-Dihydroxybenzylamine

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Altar CA, Marien MR, Marshall JF. Time course of adaptations in dopamine biosynthesis, metabolism, and release following nigrostriatal lesions: implications for behavioral recovery from brain injury. J Neurochem. 1987;48:390–399. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1987.tb04106.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aviles-Olmos I, Limousin P, Lees A, Foltynie T. Parkinson's disease, insulin resistance and novel agents of neuroprotection. Brain. 2013;136:374–384. doi: 10.1093/brain/aws009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartness TJ, Polk DR, McGriff WR, Youngstrom TG, DiGirolamo M. Reversal of high-fat diet-induced obesity in female rats. Am J Physiol. 1992;263:R790–R797. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1992.263.4.R790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bethel-Brown CS, Morris JK, Stanford JA. Young and middle-aged rats exhibit isometric forelimb force control deficits in a model of early-stage Parkinson's disease. Behav Brain Res. 2011;225:97–103. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2011.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhat A, Koul A, Rai E, Sharma S, Dhar MK, Bamezai RN. PGC-1alpha Thr394Thr and Gly482Ser variants are significantly associated with T2DM in two North Indian populations: a replicate case-control study. Hum Genet. 2007;121:609–614. doi: 10.1007/s00439-007-0352-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biswas M, Chan JY. Role of Nrf1 in antioxidant response element-mediated gene expression and beyond. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2010;244:16–20. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2009.07.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canto C, Auwerx J. PGC-1alpha, SIRT1 and AMPK, an energy sensing network that controls energy expenditure. Curr Opin Lipidol. 2009;20:98–105. doi: 10.1097/MOL.0b013e328328d0a4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canto C, Gerhart-Hines Z, Feige JN, Lagouge M, Noriega L, Milne JC, Elliott PJ, Puigserver P, Auwerx J. AMPK regulates energy expenditure b y modulating NAD+ metabolism and SIRT1 activity. Nature. 2009;458:1056–1060. doi: 10.1038/nature07813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi JS, Park C, Jeong JW. AMP-activated protein kinase is activated in Parkinson's disease models mediated b y 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2010;391:147–151. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.11.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi JY, Jang EH, Park CS, Kang JH. Enhanced susceptibility to 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine neurotoxicity in high-fat diet-induced obesity. Free Radic Biol Med. 2005;38:806–816. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2004.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clodfelder-Miller B, De Sarno P, Zmijewska AA, Song L, Jope RS. Physiological and pathological changes in glucose regulate brain Akt and glycogen synthase kinase-3. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:39723–39731. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M508824200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costes S, Huang CJ, Gurlo T, Daval M, Matveyenko AV, Rizza RA, Butler AE, Butler PC. beta-cell dysfunctional ERAD/ubiquitin/proteasome system in type 2 diabetes mediated by islet amyloid polypeptide-induced UCH-L1 deficiency. Diabetes. 2011;60:227–238. doi: 10.2337/db10-0522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geisler S, Vollmer S, Golombek S, Kahle PJ. The ubiquitin-conjugating enzymes UBE2N, UBE2L3 and UBE2D2/3 are essential for Parkin-dependent mitophagy. J Cell Sci. 2014;127:3280–3293. doi: 10.1242/jcs.146035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupte AA, Bomhoff GL, Morris JK, Gorres BK, Geiger PC. Lipoic acid increases heat shock protein expression and inhibits stress kinase activation to improve insulin signaling in skeletal muscle from high-fat-fed rats. Journal of applied physiology. 2009;106:1425–1434. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.91210.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hariri N, Thibault L. High-fat diet-induced obesity in animal models. Nutrition research reviews. 2010;23:270–299. doi: 10.1017/S0954422410000168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu G, Jousilahti P, Bidel S, Antikainen R, Tuomilehto J. Type 2 diabetes and the risk of Parkinson's disease. Diabetes Care. 2007;30:842–847. doi: 10.2337/dc06-2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koch A, Steffen J, Kruger E. TCF11 at the crossroads of oxidative stress and the ubiquitin proteasome system. Cell Cycle. 2011;10:1200–1207. doi: 10.4161/cc.10.8.15327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koo SH, Satoh H, Herzig S, Lee CH, Hedrick S, Kulkarni R, Evans RM, Olefsky J, Montminy M. PGC-1 promotes insulin resistance in liver through PPAR-alpha-dependent induction of TRB-3. Nat Med. 2004;10:530–534. doi: 10.1038/nm1044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawlor MA, Alessi DR. PKB/Akt: a key mediator of cell proliferation, survival and insulin responses? J Cell Sci. 2001;114:2903–2910. doi: 10.1242/jcs.114.16.2903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews DR, Hosker JP, Rudenski AS, Naylor BA, Treacher DF, Turner RC. Homeostasis model assessment: insulin resistance and beta-cell function from fasting plasma glucose and insulin concentrations in man. Diabetologia. 1985;28:412–419. doi: 10.1007/BF00280883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris JK, Bomhoff GL, Stanford JA, Geiger PC. Neurodegeneration in an animal model of Parkinson's disease is exacerbated b y a high-fat diet. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2010;299:R1082–R1090. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00449.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris JK, Zhang H, Gupte AA, Bomhoff GL, Stanford JA, Geiger PC. Measures of striatal insulin resistance in a 6-hydroxydopamine model of Parkinson's disease. Brain Res. 2008;1240:185–195. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2008.08.089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myhrstad MC, Husberg C, Murphy P, Nordstrom O, Blomhoff R, Moskaug JO, Kolsto AB. TCF11/Nrf1 overexpression increases the intracellular glutathione level and can transactivate the gamma-glutamylcysteine synthetase (GCS) heavy subunit promoter. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2001;1517:212–219. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4781(00)00276-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naef L, Gratton A, Walker CD. Exposure to high fat during early development impairs adaptations in dopamine and neuroendocrine responses to repeated stress. Stress. 2013;16:540–548. doi: 10.3109/10253890.2013.805321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paxinos G, Watson C. The Rat Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Puigserver P, Rhee J, Donovan J, Walkey CJ, Yoon JC, Oriente F, Kitamura Y, Altomonte J, Dong H, Accili D, Spiegelman BM. Insulin-regulated hepatic gluconeogenesis through FOXO1-PGC-1alpha interaction. Nature. 2003;423:550–555. doi: 10.1038/nature01667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salminen A, Kaarniranta K, Haapasalo A, Soininen H, Hiltunen M. AMP-activated protein kinase: a potential player in Alzheimer's disease. J Neurochem. 2011;118:460–474. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2011.07331.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santiago JA, Potashkin JA. Shared dysregulated pathways lead to Parkinson's disease and diabetes. Trends in molecular medicine. 2013;19:176–186. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2013.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- St-Pierre J, Drori S, Uldry M, Silvaggi JM, Rhee J, Jager S, Handschin C, Zheng K, Lin J, Yang W, Simon DK, Bachoo R, Spiegelman BM. Suppression of reactive oxygen species and neurodegeneration by the PGC-1 transcriptional coactivators. Cell. 2006;127:397–408. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.09.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steffen J, Seeger M, Koch A, Kruger E. Proteasomal degradation is transcriptionally controlled by TCF11 via an ERAD-dependent feedback loop. Molecular cell. 2010;40:147–158. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takaya J, Yamanouchi S, Kaneko K. A calcium-deficient diet in rat dams during gestation and nursing affects hepatic 11beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase-1 expression in the offspring. PLoS One. 2014;9:e84125. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0084125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thaler JP, Yi CX, Schur EA, Guyenet SJ, Hwang BH, Dietrich MO, Zhao X, Sarruf DA, Izgur V, Maravilla KR, Nguyen HT, Fischer JD, Matsen ME, Wisse BE, Morton GJ, Horvath TL, Baskin DG, Tschop MH, Schwartz MW. Obesity is associated with hypothalamic injury in rodents and humans. J Clin Invest. 2012;122:153–162. doi: 10.1172/JCI59660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ungerstedt U, Arbuthnott GW. Quantitative recording of rotational behavior in rats after 6-hydroxy-dopamine lesions of the nigrostriatal dopamine system. Brain Res. 1970;24:485–493. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(70)90187-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu A, Ying Z, Gomez-Pinilla F. Oxidative stress modulates Sir2alpha in rat hippocampus and cerebral cortex. Eur J Neurosci. 2006;23:2573–2580. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2006.04807.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto N, Matsubara T, Sobue K, Tanida M, Kasahara R, Naruse K, Taniura H, Sato T, Suzuki K. Brain insulin resistance accelerates Abeta fibrillogenesis by inducing GM1 ganglioside clustering in the presynaptic membranes. J Neurochem. 2012;121:619–628. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2012.07668.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y, Ma D, Wang Y, Jiang T, Hu S, Zhang M, Yu X, Gong CX. Intranasal insulin ameliorates tau hyperphosphorylation in a rat model of type 2 diabetes. J Alzheimers Dis. 2013;33:329–338. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2012-121294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Q, Niu Y, Matsumoto K, Tsuneyama K, Tanaka K, Miyata T, Yokozawa T. Chotosan ameliorates cognitive and emotional deficits in an animal model of type 2 diabetes: possible involvement of cholinergic and VEGF/PDGF mechanisms in the brain. BMC complementary and alternative medicine. 2012;12:188. doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-12-188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng B, Liao Z, Locascio JJ, Lesniak KA, Roderick SS, Watt ML, Eklund AC, Zhang-James Y, Kim PD, Hauser MA, Grunblatt E, Moran LB, Mandel SA, Riederer P, Miller RM, Federoff HJ, Wullner U, Papapetropoulos S, Youdim MB, Cantuti-Castelvetri I, Young AB, Vance JM, Davis RL, Hedreen JC, Adler CH, Beach TG, Graeber MB, Middleton FA, Rochet JC, Scherzer CR, Global PDGEC. PGC-1alpha, a potential therapeutic target for early intervention in Parkinson's disease. Science translational medicine. 2010;2:52ra73. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3001059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuurbier CJ, Keijzers PJ, Koeman A, Van Wezel HB, Hollmann MW. Anesthesia's effects on plasma glucose and insulin and cardiac hexokinase at similar hemodynamics and without major surgical stress in fed rats. Anesth Analg. 2008;106:135–142. doi: 10.1213/01.ane.0000297299.91527.74. table of contents. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]