Abstract

Background

Evidence from animal and cell line experimental studies support a beneficial role for vitamin D in prostate cancer (PCa). While the results from human studies have been mainly null for overall PCa risk, there may be a benefit for survival. We assessed the associations of circulating 25-hydroxyvitamin D [25(OH)D] and common variation in key vitamin D-related genes with fatal PCa.

Methods

In a large cohort consortium, we identified 518 fatal cases and 2986 controls with 25(OH)D data. Genotyping information for 91 single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in 7 vitamin D-related genes (VDR, GC, CYP27A1, CYP27B1, CYP24A1, CYP2R1, RXRA) was available for 496 fatal cases and 3577 controls. We used unconditional logistic regression to calculate odd ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) for the associations of 25(OH)D and SNPs with fatal PCa. We also tested for 25(OH)D-SNP interactions among 264 fatal cases and 1169 controls.

Results

We observed no statistically significant relationship between 25(OH)D and fatal PCa [OR(95% CI)extreme quartiles=0.86(0.65-1.14); p-trend=0.22] or the main effects of the SNPs and fatal PCa. There was suggestive evidence that associations of several SNPs (including 5 related to circulating 25(OH)D) with fatal PCa were modified by 25(OH)D. Individually these associations would not remain significant after considering multiple testing; however the p-value for the set-based test for CYP2R1 was 0.002.

Conclusions

In our study, we did not observe statistically significant associations for either 25(OH)D or vitamin D-related SNPs with fatal PCa. Effect modification of 25(OH)D associations by biologically plausible genetic variation may deserve further exploration.

Keywords: circulating 25-hydroxyvitamin D, vitamin D genes, fatal prostate cancer, single nucleotide polymorphisms, gene-environment interaction

Introduction

In addition to its role in bone health, vitamin D regulates expression of 3-5% of genes, many of which are related to cancer1. Evidence from animal and cell line experimental studies supports a beneficial role for vitamin D in the prevention and treatment of prostate cancer (Pca)2,3, but results from human epidemiologic studies are conflicting. Epidemiologic studies focusing on circulating 25(OH)D have not supported a protective association for higher 25(OH)D with overall PCa risk4-8. More recently, there has been growing interest in whether vitamin D may specifically influence cancer survival and prognosis9. This is particularly relevant for PCa because indolent and fatal disease may be etiologically different10. However, only a few studies have investigated the relationship between circulating 25(OH)D and PCa specific mortality; some found a protective association6,11,12, while others have not7,13.

At the same time, an increasing number of studies have explored whether common genetic variants among genes that play a role in vitamin D metabolism and signaling are associated with PCa risk. Most studies have focused on five specific SNPs in the vitamin D receptor gene (VDR), with inconsistent results14. More comprehensive studies assessing common variation across the VDR and several other vitamin D pathway genes and PCa risk have yielded few additional findings15-18. Furthermore, only two studies have assessed the relationship of common variation in these vitamin D pathway genes with the endpoint of fatal PCa; while both studies found suggestive associations, their results were not consistent6,19. A yet unexplored area is whether associations between vitamin D related SNPs and fatal PCa may be modified by circulating levels of 25(OH)D. Identification of such interactions would lend mechanistic and causal support for an association of vitamin D with PCa.

Recently, the Health Professionals Follow-up Study (HPFS) reported that higher pre-diagnostic 25(OH)D levels were associated with a 57% statistically significant reduction in the risk of fatal PCa (highest vs. lowest quartile)6. Using a pathway-based approach, the HPFS also reported that common variation in seven vitamin D-related genes (CYP27A1, CYP2R1, CYP27B1, GC, CYP24A1, RXRA, and VDR) was related to fatal PCa, in particular for VDR andCYP27A16. The genes were chosen because of laboratory evidence that they are directly involved in vitamin D metabolism and signaling.

The objectives of the current study were to follow-up on the findings from the HPFS within a large consortium of prospective cohort studies. Specifically, we 1) assessed whether men with low circulating 25(OH)D are at an increased risk of fatal PCa and 2) investigated the association of common variation in vitamin D-pathway genes with fatal PCa. Furthermore, we also explored gene-environment interactions between circulating 25(OH)D, vitamin D pathway SNPs, and fatal PCa.

Material and Methods

Study population

The Breast and PCa Cohort Consortium (BPC3) is a collaboration of well-established prospective cohort studies investigating genetic risk factors for breast and PCa and has been described in detail previously20. Studies that participated in this analysis included, the Alpha-Tocopherol, Beta-Carotene Cancer Prevention (ATBC) Study7, the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition Cohort (EPIC)5, the Health Professionals Follow-up Study (HPFS)6, the Physicians’ Health Study (PHS)21, and the Prostate, Lung, Colorectal, and Ovarian (PLCO) Cancer Screening Trial15. The respective local Institutional Review Boards approved each study. Each cohort provided a nested series of PCa cases and controls; within each cohort controls without a previous diagnosis of prostate cancer were matched to cases on factors such as age and ethnicity depending on the cohort20. In addition, covariate information including, body mass index (BMI, kg/m2), history of diabetes (yes/no), smoking status (never, current, former), and age at blood draw and diagnosis were available. We restricted the current study to men who self-reported as being of European descent.

Outcome Ascertainment

Men with incident PCa were identified through population-based cancer registries or self-report confirmed by medical records, including pathology reports. Data on disease stage and grade at the time of diagnosis were noted, when available. The primary outcome was fatal PCa risk. Cases were followed for overall mortality and PCa specific mortality using a combination of death certificates, medical record review, and population registries.

25(OH)D Assessment

Pre-diagnostic circulating 25(OH)D levels were assayed separately in each study and were available for 518 fatal PCa cases and 2986 controls. Details of 25(OH)D assessment, including type of assay and quality control measures, specific to each cohort has been previously published5-7,15,21 (See also Supplementary Table 1). Some studies conducted multiple batches of assays at differing time points (e.g. HPFS selected case and controls in four separate batches and each batch was assayed at a different time point: blood draw to January 1996, February 1996 to January 1998, February 1998 to January 2000, and February 2000 to January 2004). To account for study, season of blood draw, and laboratory variation due to multiple batches of assays conducted at differing time points within a study, we created study-, season- and batch- quartile and median cut points based on levels in the control subjects. Seasons were defined as summer (June to August)/autumn (September to November) and spring (March to May)/winter (December to February). We did not analyze absolute cut points of 25(OH)D because of substantial variation among the different assays.

Genotyping

A subset of the BPC3 cases with aggressive PCa, defined as Gleason 8-10 or stage C/D, and controls were included in a Genome Wide Association Study (GWAS) to identify novel risk variants for aggressive PCa20. Genotyping was performed for the majority of the subjects using the Illumina Human 610-Quad array, but some subjects from the PLCO were genotyped on other Illumina arrays (i.e. HumanHap 317K+240K or 550K). Quality control measures have been ssdescribed in detail elsewhere20. In brief, samples were excluded if genotyping call rate was <95%, or autosomal heterozygosity was <0.25 or >0.35. Additional common variants and missing values were imputed using MACH and the Phase II CEU HapMap data22. We were able to extract genotypes or a proxy (R2>=0.8) for 88 of the 95 SNPs included in the original study. Four of the SNPs were unavailable including the VDR SNPs rs2228570 (Fok1), rs11168275, rs11574032, and RXRA SNP rs34312136 and three were partially tagged (0.6<R2<0.8), rs10875693 (VDR), rs7853934, rs41400444 (RXRA). Of the men with GWAS data there were 264 fatal PCa cases and 1169 controls who also had overlapping information on circulating 25(OH)D.

Statistical Methods

All statistical tests were two-sided and were conducted using SAS v9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) and R (http://www.r-project.org/) statistical packages. We used logistic regression to calculate the odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) for the associations of circulating 25(OH)D and vitamin D pathway-SNPS with risk of incident fatal PCa compared to controls. The primary models used data pooled across all 5 cohorts and were adjusted for age at diagnosis (cases) or selection (controls) and cohort.

For 25(OH)D, we also created models adjusting for year of blood draw, time from blood draw to diagnosis, BMI (kg/m2), diabetes history (y/n), and smoking (never, current, former). The lowest quartile of 25(OH)D was used as the reference category and tests for trend used an ordinal variable (values of 1-4) corresponding to the quartile in which the individual's circulating 25(OH)D fell. We conducted a sensitivity analysis excluding men who were diagnosed with PCa within 2 years after blood draw. For the SNP analyses, we used an allele-dosage model. Finally, we conducted exploratory analyses to test for SNP-25(OH)D interactions in relation to fatal PCa risk among the subset of men with both circulating 25(OH)D and genetic data. We performed stratified analysis for the association of the SNPs with fatal PCa in those men with high vs. low 25(OH)D (dichotomized at the median). We tested for multiplicative interaction by adding a cross-product term to the model (SNP*25(OH)D) and assessed significance with the Wald test. To improve power of the statistical test for interaction, we used a continuous measure of 25(OH)D that was standardized for season, cohort and batch using the method described by Rosner et al.23. Briefly, in this method, beta coefficients from a linear regression model of 25(OH)D with batch, season and cohort indicators were averaged; for each specific cohort-season-batch combination, the difference between the corresponding beta coefficient from the model and the average coefficient was subtracted from the unadjusted 25(OH)D value to create a continuous measurement that was standardized to the average cohort-season-batch.

We implemented set-based tests across the entire pathway of 7 genes and at the individual gene level for the association with fatal PCa and for SNP-25(OH)D interactions. Set-based test may have enhanced power due to aggregating multiple signals within a set, leveraging the correlation between SNPs, and reducing the multiple testing burden. The mathematical details of the logistic regression kernel machine models and gene-environment set-based association test (GESAT) is described elsewhere24-27. In brief, the kernel machine model treats each of the included SNPs as a random effect; desired covariates (e.g. age and study) are entered as fixed effects. The joint effect of the entire SNP-set is considered and the degrees of freedom are calculated with respect to the correlation between the SNPs in the set, improving the power of the hypothesis test. The null hypothesis that the variance of the SNP random effects is zero (i.e. that the SNPs individually or jointly are not associated with disease) can be tested using a score test. Similarly, the GESAT27 considers the coefficients of the gene-environment interaction terms as random effects and develops a variance component score test within the induced generalized linear mixed model framework.

We report nominal p-values, but we also calculated the effective number of independent tests for the individual SNP associations28. After accounting for linkage disequilibrium, the 91 SNPs corresponded to 77 independent tests; therefore a p-value significance threshold of 0.0006 controls the experiment-wide type I error rate at the 0.05 level.

Results

Supplementary Tables 2a-c describe characteristics of the fatal PCa cases and controls for those with a) circulating 25(OH)D b) genotype data, and c) both circulating 25(OH)D and GWAS information. Those participating in the GWAS were more heavily weighted to higher stage and grade due to the selection criteria described above.

25(OH)D and fatal PCa

Among the men with pre-diagnostic circulating 25(OH)D, 518 died from PCa over a median follow-up time of 8.1 years after diagnosis. The median levels of 25(OH)D in the first and fourth quartile respectively were 14.4 ng/mL (35.9 nmol/L) and 33.0 ng/mL (82.4 nmol/L). Table 1 shows the ORs and 95% CI's by quartiles of circulating 25(OH)D for risk of fatal PCa, adjusted for age at blood draw, time from blood draw to diagnosis and cohort, BMI. There was no significant association of 25(OH)D and risk of fatal PCa across the five cohorts combined (OR: 0.86; 95% CI: 0.65-1.14 (highest vs. lowest quartile); p-trend=0.22). Three of the five cohorts showed an inverse trend, but only one (HPFS) was statistically significant (Supplementary Table 3). When we excluded HPFS, the pooled results remained non-significant (ORhighest vs. lowest quartile: 0.96; 95% CI: 0.70, 1.31; p-trend=0.73) (data not shown). There was no evidence for heterogeneity between studies when we looked at the estimates for the highest vs. lowest quartiles using the Cochran's Q test. Additional adjustment for diabetes status and smoking did not change the results.

Table 1.

Odds ratios and confidence intervals for quartiles of circulating 25(OH)D* and fatal prostate cancer pooled across 5 cohorts

| Quartile of 25(OH)D | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| q1 | q2 | q3 | q4 | p-trend | |

| Median 25(OH)D level (ng/mL)# | 14.4 | 20.1 | 24.8 | 33.0 | |

| cases/controls | 141/740 | 131/751 | 120/757 | 126/738 | |

| OR (95% CI)^ | 1.00 (ref) | 0.87(0.66-1.15) | 0.79(0.60-1.05) | 0.86(0.65-1.14) | 0.22 |

| Results excluding cases diagnosed within two years of blood draw | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quartile of 25(OH)D | |||||

| q1 | q2 | q3 | q4 | p-trend | |

| cases/controls | 113/740 | 112/751 | 103/757 | 110/738 | |

| OR (95% CI)^ | 1.00 (ref) | 0.92(0.68-1.23) | 0.85(0.63-1.16) | 0.94(0.69-1.27) | 0.59 |

25(OH)D quartiles are batch, season (summer/fall vs winter/spring) and cohort specific

among controls the median value of 25(OH)D in nmol/L for ql to q4 respectively: 35.9, 50.2, 61.9, 82.4

Adjusted for age at blood draw, time from blood draw to diagnosis and cohort, BMI

Vitamin D pathway common genetic variation and fatal PCa

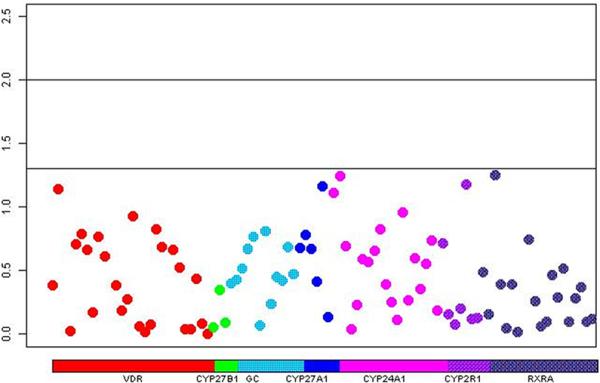

Among the men with available genotype information, 496 died of PCa. Figure 1 shows the p-value for the per-allele associations of each SNP and fatal PCa and Supplementary Table 4 provides the OR and 95% CI for each SNP. None of the SNPs were significantly associated with fatal PCa and the global p-value across the pathway from the kernel machine test was not significant (p=0.44).

Figure 1.

Manhattan plot showing p-values for the association of each individual vitamin D SNP and fatal prostate cancer risk. Each SNP is color coded by gene and represented by a circle on the plot.

SNP-25(OH)D interactions and fatal PCa

In the subset of men who had both circulating 25(OH)D and genotype data, there were 264 PCa deaths. Table 2 details the SNPs that were either nominally significant in strata of high vitamin D (n=6) or low vitamin D (n=11) or had a p-interaction<0.05 (n=9); none of the SNPs remained statistically significant after considering multiple testing so these associations may be due to chance. However, the results of the GESAT test across the entire pathway was p=0.06 and at the gene-level CYP2R1 was statistically significant (p=0.002). Supplementary Table 5 includes the results for all of the SNPs and the GESAT tests. We also assessed whether the vitamin D pathway SNPs were associated with circulating 25(OH)D levels. Our results replicated SNPs in the genes GC and CYP2R1 known to be related to circulating 25(OH)D from previous GWAS15 (Supplementary Table 6). Five of these SNPs (GC: rs1155563 and CYP2R1: rs2060793, rs12794714, rs1562902, and rs11023374) were among the SNPs whose association with fatal PCa differed by circulating 25(OH)D level (Table 2).

Table 2.

Associations of nominally significant vitamin D pathway SNPS and lethal prostate cancer stratified by high vs. low 25(OH)D

| Gene: SNP (Major/Minor allele) | OR* and 95% CI for low 25(OH)D strata | p-value | OR* and 95% CI for high 25(OH)D strata | p-value | p-interaction# |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VDR:rs2239186(A,G) | 1.26(0.88-1.78) | 0.20 | 1.44(1.01-2.05) | 0.04 | 0.44 |

| VDR:rs2189480(G,T) | 1.44(1.05-1.97) | 0.02 | 1.12(0.83-1.50) | 0.47 | 0.60 |

| VDR:rs2283342(A,G) | 1.07(0.72-1.57) | 0.75 | 1.59(1.09-2.32) | 0.02 | 0.15 |

| VDR:rs12721364(G,A) | 1.34(0.89-2.02) | 0.16 | 0.67(0.44-1.02) | 0.06 | 0.05 |

| VDR:rs10875693(T,A) | 0.66(0.46-0.96) | 0.03 | 1.16(0.82-1.64) | 0.42 | 0.23 |

| VDR:rs4760648(C,T) | 0.85(0.63-1.14) | 0.27 | 1.23(0.90-1.69) | 0.19 | 0.03 |

| GC:rs1155563(T,C) | 0.96(0.69-1.33) | 0.81 | 1.54(1.10-2.14) | 0.01 | 0.12 |

| GC:rs1491716(G,A) | 0.50(0.25-0.98) | 0.04 | 1.25(0.68-2.30) | 0.48 | 0.70 |

| GC:rs6817912(C,T) | 1.93(1.00-3.70) | 0.05 | 0.93(0.48-1.81) | 0.83 | 0.72 |

| GC:rs12640179(C,G) | 1.81(0.99-3.31) | 0.05 | 0.72(0.36-1.48) | 0.37 | 0.03 |

| CYP27A1:rs647952(A,G) | 0.20(0.05-0.74) | 0.02 | 1.28(0.48-3.41) | 0.63 | 0.51 |

| CYP2R1:rs2060793(G,A) | 1.34(1.00-1.79) | 0.05 | 1.13(0.84-1.52) | 0.42 | 0.03 |

| CYP2R1:rs12794714(G,A) | 0.69(0.51-0.93) | 0.01 | 0.86(0.63-1.16) | 0.32 | 0.04 |

| CYP2R1:rs1562902(T,C) | 1.41(1.04-1.90) | 0.03 | 1.05(0.79-1.42) | 0.72 | 0.004 |

| CYP2R1:rs10832312(T,C) | 1.65(1.02-2.65) | 0.04 | 0.88(0.52-1.49) | 0.64 | 0.04 |

| CYP2R1:rs11023374(T,C) | 0.75(0.53-1.07) | 0.11 | 0.97(0.68-1.38) | 0.85 | 0.01 |

| CYP24A1:rs2585413(G,A) | 0.93(0.67-1.29) | 0.67 | 0.71(0.51-0.98) | 0.04 | 0.48 |

| CYP24A1:rs2585415(G,A) | 0.99(0.72-1.35) | 0.93 | 0.70(0.51-0.96) | 0.03 | 0.21 |

| CYP24A1:rs927650(C,T) | 0.99(0.73-1.33) | 0.94 | 1.50(1.11-2.04) | 0.009 | 0.19 |

| CYP24A1:rs3787555(C,A) | 1.40(1.00-1.96) | 0.05 | 0.81(0.57-1.16) | 0.25 | 0.78 |

| RXRA:rs1536475(G,A) | 1.09(0.73-1.61) | 0.69 | 0.79(0.51-1.20) | 0.27 | 0.03 |

Per-minor allele odds ratio for fatal prostate cancer, adjusted for age at diagnosis

Wald p-value for SNP coded (0,1,2)*25(OH)D (continuous); 25(OH)D was standardized by cohort, season, and laboratory assay batch.

Discussion

In our large cohort consortium we did not find evidence to support associations of circulating 25(OH)D or common variation in key vitamin D pathway genes with risk of fatal PCa. In our exploratory analysis for SNP-25(OH)D interactions, several nominally significant associations between vitamin D pathway SNPs and fatal PCa were observed in the stratified analysis at either high or low circulating 25(OH)D levels and a gene-level significant association was observed for CYP2R1.

The pooled association across all 5 cohorts between higher circulating 25(OH)D and risk of fatal PCa was in the protective direction, but was not statistically significant. Three of the five cohorts showed an inverse trend, but only HPFS (as published previously6) was statistically significant. Other studies have published findings on circulating 25(OH)D and fatal PCa7,12,13. The ATBC study (294 fatal PCa cases) did not find a statistically significant association between prospectively collected circulating 25(OH)D and fatal PCa7. Two studies assessed the association of progression to PCa specific mortality and 25(OH)D in post-diagnostic blood. A population-based study performed in 1476 men with PCa in the metropolitan Seattle-Puget Sound area found no significant association for progression to PCa specific mortality13, while a different study based in 160 Norwegian men observed a statistically significant 67% decreased risk of progression with medium to high 25(OH)D levels compared to low levels (<50nmol/L), especially in men receiving hormone therapy12. A study combining data from the HPFS and the PHS also found a protective association between pre-diagnostic circulating 25(OH)D and PCa mortality among cases, but the association mostly driven by the HPFS11. A few studies have generated concern that there may be an increased risk of aggressive PCa with higher circulating 25(OH)D15,29; our study does not support an increased risk of fatal PCa at higher circulating 25(OH)D.

Varying results by cohort could be due to differences in screening practices, severity of disease at diagnosis, prevalence of factors that could modify the association, or chance. PLCO and HPFS were both highly screened populations and showed the strongest protective associations for vitamin D with fatal PCa. It is difficult to explain this observation, but one potential hypothesis is that vitamin D maybe more effective in preventing progression in PSA screened populations where disease is treated early; cancers detected at a later point in the natural history of the disease could be more likely to be resistant to this vitamin D effect. There were no major differences in the range of vitamin D levels in each cohort; in particular the median levels in the first and fourth quartiles in the controls were comparable among the cohorts (Supplementary Table 3). Overall, the difference between the medians of the first and fourth quartiles of 25(OH)D in the controls was 18.6 ng/mL (46.5 nmol/L) with more than a quarter of the men classified as at risk for having inadequate vitamin D levels (<20ng/mL or <50 nmol/L) (Table 2). While a single measurement of circulating 25(OH)D has been shown to have reasonable validity over time30, multiple measurements would more accurately reflect long-term exposure. Additionally, the 25(OH)D assays differed across cohort and were not calibrated to a common assay nor standardized to an accepted gold standard, preventing the use of absolute cut points for comparisons.

We did not observe evidence for confounding by BMI, diabetes or smoking, but we did not have information on other potential confounders such as physical activity. For example, if higher levels of physical activity is associated with higher circulating 25(OH)D6 and lower risk for PCa mortality the observed results could be biased away from the null.

We did not observe any statistically significant main effects of common variation in key vitamin D pathway-related genes on risk fatal PCa. We did not replicate the findings in the prior HPFS study6 or the findings from a case-only study that assessed 48 tag-SNPs in VDR, CYP27B1, and CYP24A1 and progression to PCa mortality19.

To our knowledge this is the first study to assess interactions between a comprehensive set of SNPs in key genes related to vitamin D signaling and metabolism and levels of circulating 25(OH)D in relation to fatal PCa. The overall GESAT pathway p-value=0.06 and suggestive effect modification by circulating 25(OH)D on the association of a number of SNPs and fatal PCa was observed. Several of these SNPs were located in GC (the vitamin D binding protein) and CYP2R1 (a 25-hydroxylase)—genes which have been observed to influence circulating 25(OH)D levels31. The strongest evidence for effect modification was in the CYP2R1 gene; 5 SNPs had nominally significant p-interaction and the gene level GESAT was statistically significant (p-value=0.002). Interestingly, four of these five CYP2R1 SNPS were associated with levels of circulating 25(OH)D in our study. On average, men who carried an allele that was associated with higher circulating 25(OH)D in the general population, but who still had low circulating 25(OH)D levels were at higher risk for fatal PCa. The other SNPs were mainly located in CYP24A1, an enzyme critical for the catabolism of vitamin D, and VDR, the key nuclear receptor that mediates the genomic effects of vitamin D. Overexpression of CYP24A1 has been shown to correlate with worse outcomes in several solid tumors, including prostate32. Conversely, higher VDR expression has been associated with better PCa survival33. Given the strong biological plausibility that circulating 25(OH)D may affect the association of these SNPs with fatal PCa, future study is warranted.

A few studies have assessed circulating 25(OH)D-SNP interactions for overall PCa incidence. Most of these studies were small candidate gene studies that focused mainly on VDR polymorphisms including Bsm1 (rs1544410)15,34,35, Cdx2 (rs11568820)15,35, and Fok1 (rs2228570/rs10735810)15,21,35-37 and the results have been inconclusive. Our study was unable to assess Fok1 and we did not observe any gene-environment interactions with Cdx2 or Bsm1. Recently, a study of 1514 participants found that a variant in VDR (rs7968585) modified the association of 25(OH)D and a composite clinical outcome (incident hip fracture, myocardial infarction, cancer incidence, and total mortality). This finding was further replicated through a meta-analysis of 3 independent cohorts38. Although not statistically significant, our data were consistent with this finding. Rs7967152 (r2=0.87 with rs7968585) showed a stronger association with fatal PCa in men with low 25(OH)D: OR(95% CI)low 25(OH)D: 1.30 (0.97-1.74), p=0.08 compared to those with high 25(OH)D: OR(95% CI)high 25(OH)D: 0.89(0.66-1.20), p=0.46 (Supplementary Table 6).

The relationship between circulating 25(OH)D and the prostate environment is complex and could be mediated by expression of several vitamin-D related genes. It is possible that circulating levels of 25(OH)D do not adequately reflect the bioavailability in the prostate tissue as CYP27B1 is expressed in the prostate and can synthesize 1,25(OH)2D from 25(OH)D within the prostate. Nonetheless, a clinical trial of vitamin D supplementation indicated that levels of vitamin D metabolites (25(OH)D and 1,25(OH)2D) in prostate tissue correlated positively with serum circulating levels39. The influence of 25(OH)D in the prostate environment may be further mediated by expression of VDR or CYP24A1 in prostate tissue. Higher expression of VDR in prostate tumor tissue has been associated with a decreased risk of PCa progression33 and increased expression of CYP24A1 was observed to be associated with advanced stage PCa and resistance to vitamin D-based therapies32. Studies integrating circulating 25(OH)D with tumor molecular profiling could shed light on the inconsistent results to date.

A major strength of this study was the combination of several large cohort studies with prospective blood collection and relatively long-term and complete follow-up, allowing for the assessment of fatal PCa, an endpoint that has been traditionally difficult to study epidemiologically with substantial numbers of outcomes due to the long natural history of the disease. With a median follow-up of 8.1 years, we were able to capture 518 fatal prostate cancer cases. Even so, longer follow-up would allow for greater accrual of deaths further out in the natural history of the disease. Finally, after subsetting the men who had both levels of circulating 25(OH)D and genotyping data, our sample size was reduced, limiting our power to detect interactions.

Conclusions

We did not find strong evidence to support the hypothesis that circulating 25(OH)D or common variation in key vitamin D pathway genes is related to a decreased risk of fatal PCa. We observed suggestive modification of the association between some of the SNPs and fatal PCa by circulating 25(OH)D levels, especially in CYP2R1. These latter findings could be further assessed in other cohort studies or in clinical trials of vitamin D supplementation or vitamin D agonists.

Supplementary Material

Condensed Abstract: Given the high prevalence of prostate cancer (PCa) and the wide international variation in vitamin D status, identifying causal links between the two could have a large public health impact. Few studies have addressed risk of fatal PCa. In this study, we did not observe a convincing association of circulating 25(OH)D or SNPs in key vitamin D-related genes with fatal PCa. However, interactions between biologically relevant SNPs and circulating 25(OH)D with respect to fatal PCa may deserve further investigation.

Acknowledgments

The BPC3 was supported by the US NIH, NCI under cooperative agreements U01-CA98233, U01-CA98710, U01-CA98216, U01-CA98758, R01 CA63464, P01 CA33619, R37 CA54281 and UM1 CA164973 and Intramural Research Program of NIH/NCI. Additional funding as follows:

The Danish study: Diet, Cancer and Health: Danish Cancer Society.

The EPIC study of vitamin D and prostate cancer and the EPIC-UK cohorts: Cancer Research UK and Medical Research Council UK.

EPIC-Greece: Hellenic Health Foundation.

EPIC-Spain: Health Research Fund (FIS); Regional Governments of Andalucía, Asturias, Basque Country, Murcia and Navarra; and ISCIII RETIC (RD06/0020).

EPIC-Italy: Sicilian government, Aire-Onlus Ragusa.

MORGEN-EPIC: European Commission (DG-SANCO), International Agency for Research on Cancer, the Dutch Ministry of Public Health, Welfare and Sports (VWS), and Statistics Netherlands.

IMS and TG: NCI National Research Service Award (T32 CA09001).

IMS: U.S. Army Department of Defense Prostate Cancer Post-doctoral Fellowship.

LAM: Prostate Cancer Foundation.

The authors thank:

Drs. Christine Berg and Philip Prorok, Division of Cancer Prevention, NCI, the screening center investigators and staff of the PLCO Cancer Screening Trial, Mr Thomas Riley and staff at Information Management Services, Inc., and Ms Barbara O'Brien and staff at Westat, Inc. for their contributions to the PLCO Cancer Screening Trial.

Hongyan Huang for assistance in preparing the data.

The participants and staff of the Health Professionals Follow-up Study for their valuable contributions as well as the following state cancer registries for their help: AL, AZ, AR, CA, CO, CT, DE, FL, GA, ID, IL, IN, IA, KY, LA, ME, MD, MA, MI, NE, NH, NJ, NY, NC, ND, OH, OK, OR, PA, RI, SC, TN, TX, VA, WA, WY. The authors assume full responsibility for analyses and interpretation of these data.

Footnotes

Authors from the Breast and Prostate Cancer Cohort Consortium Group:

Amanda Black, Christine D. Berg, H B(as) Bueno-de-Mesquita, Susan M Gapstur, Christopher Haiman, Brian Henderson, Robert Hoover, David J Hunter, Mattias Johansson, Timothy J Key, Kay-Tee Khaw, Loic Le Marchand, Jing Ma, Marjorie L. McCullough, Afshan Siddiq, Meir Stampfer, Daniel O Stram, Victoria L Stevens Dimitrios Trichopoulos, Rosario Tumino, Walter Willett, Regina G Ziegler, Tilman Kühn, Aurelio Barricarte, Anne Tjønneland

Conflicts of Interests: None

References

- 1.Deeb KK, Trump DL, Johnson CS. Vitamin D signalling pathways in cancer: potential for anticancer therapeutics. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2007;7(9):684–700. doi: 10.1038/nrc2196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Giovannucci E. The epidemiology of vitamin D and cancer incidence and mortality: a review (United States). Cancer Causes Control. 2005;16(2):83–95. doi: 10.1007/s10552-004-1661-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Feldman D, Krishnan AV, Swami S, Giovannucci E, Feldman BJ. The role of vitamin D in reducing cancer risk and progression. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2014;14(5):342–357. doi: 10.1038/nrc3691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ahn J, Peters U, Albanes D, et al. Serum vitamin D concentration and prostate cancer risk: a nested case-control study. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2008;100(11):796–804. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djn152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Travis RC, Crowe FL, Allen NE, et al. Serum vitamin D and risk of prostate cancer in a case-control analysis nested within the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC). Am. J. Epidemiol. 2009;169(10):1223–1232. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwp022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shui IM, Mucci LA, Kraft P, et al. Vitamin D-related genetic variation, plasma vitamin D, and risk of lethal prostate cancer: a prospective nested case-control study. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2012;104(9):690–699. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djs189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Albanes D, Mondul AM, Yu K, et al. Serum 25-hydroxy vitamin D and prostate cancer risk in a large nested case-control study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2011;20(9):1850–1860. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-11-0403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gilbert R, Martin RM, Beynon R, et al. Associations of circulating and dietary vitamin D with prostate cancer risk: a systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis. Cancer Causes Control. 2011;22(3):319–340. doi: 10.1007/s10552-010-9706-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Toriola AT, Nguyen N, Scheitler-Ring K, Colditz GA. Circulating 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels and prognosis among cancer patients: a systematic review. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2014;23(6):917–933. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-14-0053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Giovannucci E, Liu Y, Platz EA, Stampfer MJ, Willett WC. Risk factors for prostate cancer incidence and progression in the health professionals follow-up study. Int. J. Cancer. 2007;121(7):1571–1578. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fang F, Kasperzyk JL, Shui I, et al. Prediagnostic plasma vitamin D metabolites and mortality among patients with prostate cancer. PLoS ONE. 2011;6(4):e18625. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0018625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tretli S, Hernes E, Berg JP, Hestvik UE, Robsahm TE. Association between serum 25 (OH)D and death from prostate cancer. Br. J. Cancer. 2009;100(3):450–454. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Holt SK, Kolb S, Fu R, Horst R, Feng Z, Stanford JL. Circulating levels of 25-hydroxyvitamin D and prostate cancer prognosis. Cancer Epidemiol. 2013;37(5):666–670. doi: 10.1016/j.canep.2013.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yin M, Wei S, Wei Q. Vitamin D Receptor Genetic Polymorphisms and Prostate Cancer Risk: A Meta-analysis of 36 Published Studies. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Med. 2009;2(2):159–175. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ahn J, Albanes D, Berndt SI, et al. Vitamin D-related genes, serum vitamin D concentrations and prostate cancer risk. Carcinogenesis. 2009;30(5):769–776. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgp055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Holt SK, Kwon EM, Peters U, Ostrander EA, Stanford JL. Vitamin D pathway gene variants and prostate cancer risk. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2009;18(6):1929–1933. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-09-0113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Holick CN, Stanford JL, Kwon EM, Ostrander EA, Nejentsev S, Peters U. Comprehensive association analysis of the vitamin D pathway genes, VDR, CYP27B1, and CYP24A1, in prostate cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2007;16(10):1990–1999. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-0487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mondul AM, Shui IM, Yu K, et al. Genetic variation in the vitamin d pathway in relation to risk of prostate cancer--results from the breast and prostate cancer cohort consortium. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2013;22(4):688–696. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-13-0007-T. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Holt SK, Kwon EM, Koopmeiners JS, et al. Vitamin D pathway gene variants and prostate cancer prognosis. Prostate. 2010;70(13):1448–1460. doi: 10.1002/pros.21180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schumacher FR, Berndt SI, Siddiq A, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies new prostate cancer susceptibility loci. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2011;20(19):3867–3875. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddr295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li H, Stampfer MJ, Hollis JB, et al. A prospective study of plasma vitamin D metabolites, vitamin D receptor polymorphisms, and prostate cancer. PLoS Med. 2007;4(3):e103. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0040103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.International HapMap C. Frazer KA, Ballinger DG, et al. A second generation human haplotype map of over 3.1 million SNPs. Nature. 2007;449(7164):851–861. doi: 10.1038/nature06258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rosner B, Cook N, Portman R, Daniels S, Falkner B. Determination of blood pressure percentiles in normal-weight children: some methodological issues. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2008;167(6):653–666. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwm348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wu MC, Kraft P, Epstein MP, et al. Powerful SNP-set analysis for case-control genome-wide association studies. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2010;86(6):929–942. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2010.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu D, Ghosh D, Lin X. Estimation and testing for the effect of a genetic pathway on a disease outcome using logistic kernel machine regression via logistic mixed models. BMC Bioinformatics. 2008;9:292. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-9-292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lin X, Cai T, Wu MC, et al. Kernel machine SNP-set analysis for censored survival outcomes in genome-wide association studies. Genet. Epidemiol. 2011;35(7):620–631. doi: 10.1002/gepi.20610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lin X, Lee S, Christiani DC, Lin X. Test for interactions between a genetic marker set and environment in generalized linear models. Biostatistics. 2013;14(4):667–681. doi: 10.1093/biostatistics/kxt006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gao X. Multiple testing corrections for imputed SNPs. Genet. Epidemiol. 2011;35(3):154–158. doi: 10.1002/gepi.20563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kristal AR, Till C, Song X, et al. Plasma vitamin D and prostate cancer risk: results from the Selenium and Vitamin E Cancer Prevention Trial. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2014;23(8):1494–1504. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-14-0115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hofmann JN, Yu K, Horst RL, Hayes RB, Purdue MP. Long-term variation in serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D concentration among participants in the Prostate, Lung, Colorectal, and Ovarian Cancer Screening Trial. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 2010;19(4):927–931. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-09-1121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang TJ, Zhang F, Richards JB, et al. Common genetic determinants of vitamin D insufficiency: a genome-wide association study. Lancet. 2010;376(9736):180–188. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60588-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tannour-Louet M, Lewis SK, Louet JF, et al. Increased expression of CYP24A1 correlates with advanced stages of prostate cancer and can cause resistance to vitamin D3-based therapies. FASEB J. 2014;28(1):364–372. doi: 10.1096/fj.13-236109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hendrickson WK, Flavin R, Kasperzyk JL, et al. Vitamin D receptor protein expression in tumor tissue and prostate cancer progression. J. Clin. Oncol. 2011;29(17):2378–2385. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.30.9880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ma J, Stampfer MJ, Gann PH, et al. Vitamin D receptor polymorphisms, circulating vitamin D metabolites, and risk of prostate cancer in United States physicians. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 1998;7(5):385–390. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mikhak B, Hunter DJ, Spiegelman D, Platz EA, Hollis BW, Giovannucci E. Vitamin D receptor (VDR) gene polymorphisms and haplotypes, interactions with plasma 25-hydroxyvitamin D and 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D, and prostate cancer risk. The Prostate. 2007;67(9):911–923. doi: 10.1002/pros.20570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.John EM, Schwartz GG, Koo J, Van Den Berg D, Ingles SA. Sun exposure, vitamin D receptor gene polymorphisms, and risk of advanced prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 2005;65(12):5470–5479. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-3134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bodiwala D, Luscombe CJ, French ME, et al. Polymorphisms in the vitamin D receptor gene, ultraviolet radiation, and susceptibility to prostate cancer. Environ. Mol. Mutagen. 2004;43(2):121–127. doi: 10.1002/em.20000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Levin GP, Robinson-Cohen C, de Boer IH, et al. Genetic variants and associations of 25-hydroxyvitamin D concentrations with major clinical outcomes. JAMA. 2012;308(18):1898–1905. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.17304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wagner D, Trudel D, Van der Kwast T, et al. Randomized clinical trial of vitamin D3 doses on prostatic vitamin D metabolite levels and ki67 labeling in prostate cancer patients. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2013;98(4):1498–1507. doi: 10.1210/jc.2012-4019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.