Abstract

Objectives

To compare complication and continuation rates of the levonorgestrel intrauterine system (LNG-IUS) with the subdermal etonogestrel (ENG) implant across the US among women 15 – 44 years of age.

Study Design

A retrospective study of health insurance claims records from 2007–2011 identified a cohort of women who had LNG-IUS (n=79,920) or ENG implants (n=7,374) inserted and had insurance coverage for 12 months post-insertion. Claims for complications were examined 12 months after insertion, or until removal of either device within each of three age groups.

Results

After its introduction in 2007, the frequency of ENG implants increased each year and almost 1/3 of all insertions were in teenagers. However, among women ≤ 24 years old who had delivered an infant in the prior 8 weeks, a LNG-IUS was more likely to be inserted than an ENG implant (P < .05). The most frequent complications with both methods were related to abnormal menstruation, which was more likely to occur among ENG implant users. Overall, 83–88% of the entire sample used their chosen method for at least 12 months. The odds of continuation were similar for both methods among teenagers, but ENG implants were more likely to be removed prematurely among women 20 – 24 years old (OR 1.21, 95% CI: 1.06–1.39) and 25 – 44 years old (OR 1.49, 95% CI: 1.35–1.64).

Conclusions

Both of these long-acting contraceptive methods are well tolerated among women of all ages, and demonstrate high continuation rates.

Keywords: etonogestrel implant, intrauterine device, levonorgestrel intrauterine systems, long-acting reversible contraception

Background

During 2008, more than 50% of all pregnancies in the US were unplanned.1 This high rate of unintended pregnancies could be significantly reduced through increased use of highly effective long-acting reversible contraception (LARC), such as subdermal etonogestrel (ENG) implants and intrauterine devices (IUDs). The ENG implant has a failure rate approaching 0% while the levonorgestrel intrauterine system (LNG-IUS) has a low failure rate of 0.2% over the course of one year.2,3 In spite of its demonstrated high efficacy, relatively few women in the US are prescribed LARC each year.4 Although increasing in recent years, only 5% of sexually active adolescent and young women reported using IUDs between 2002 and 2010.4 In 2009, less than 1% of US women using contraceptives reported using ENG implants, although this may be due to the limited time they had been available.5 As a result of LARC’s meager use, most women of reproductive age who desire contraception are still prescribed less effective methods.

One reason for the low rate of LARC utilization may be concerns that it has side effects or increases the risk of pelvic inflammatory disease (PID). For example, ENG users often experience irregular or frequent bleeding.6 Moreover, concerns about future fertility appear to be the reason that providers infrequently recommend IUDs,7 even though the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists states that IUDs are safe to use in teens and nulliparous women. As a result of these concerns, more than half of US health practitioners provide IUDs rarely or never to nulliparous women or teenagers.4,8 Two recent studies partially addressed these concerns by demonstrating that PID, uterine perforation, and ectopic pregnancies occur infrequently (<1%) during the first year of use among women using modern IUDs.9,10 These studies did not, however, directly compare side effects of the ENG implant with LNG-IUS using age-stratified analyses.11 As one Cochrane review pointed out, these types of comparisons are important to help providers counsel their patients on the best type of LARC for them.2

Finally, it is important to understand how long women continue to use different LARC methods. Prior studies have shown that LARC is used significantly longer than oral contraceptive pills, patches, rings, or barrier methods, and satisfaction with LNG-IUS and the ENG implant is high.12,13 However, these research studies were conducted in populations that may differ from the general population. Further, these studies did not directly compare continuation rates between different LARC methods within different age groups, but instead assessed continuation of each method separately. The objective of this study was to compare two different methods of LARC (LNG-IUS vs. ENG implant) by examining 1) relative use trends over time, 2) complication rates, and 3) continuation rates among teenagers 14–19 years of age versus women 20 – 24 years and 25 – 44 years of age.

Methods

This retrospective cohort study used 2007–2011 health insurance claims from Clinformatics™ DataMart, a product of OptumInsight Life Sciences, Inc. (Eden Prairie, MN). The dataset contains information on more than 45 million individuals, of which approximately 80% purchase their health insurance through their employer. The dataset has been de-identified and does not contain any information on socioeconomic status or race/ethnicity. In general, this dataset is roughly representative of the US working population, with some overrepresentation in the South. Data reflect only health claims that have been paid by the insurance company, based on submissions from doctors across the US. This study was exempted from full review by the University of Texas Medical Branch Institutional Review Board.

For our study, we included only the LNG-IUS and the ENG implant LARC devices in order to directly compare these methods. We did not include the copper IUD because it is used rarely among teenagers, and the continuation and side effects of this method have already been compared to the LNG-IUS in different age groups.9 We identified 131,634 women between 15–44 years of age that had a claim for the insertion of a LNG-IUS and 12,381 for an ENG implant between 2007 and 2011, with one year of follow-up. Including follow-up time, our results extended into 2012. Subjects were chosen if they had a Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System (HCPCS) code (J7302, S4989, S4981) combined with either a Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) code (58300) or International Classification of Diseases, 9th edition (ICD-9) code (69.7, V25.1, V25.42) that indicated insertion of the LNG-IUS. Insertion of the ENG implant device was determined by a HCPCS code (J7307).

Of all women who had a LNG-IUS inserted during 2007 – 2011, a total of 79,920 were included in the study after excluding those who were immunocompromised (042, 043, 044, 279.0, 279.1, 279.2, 279.3, 795.71, V08), autistic or mentally impaired (299, 299.0, 299.00, 299.01, 317, 318), and not enrolled for 12 continuous months from the date of LARC insertion (Supplementary Figure 1). After applying the same criteria, 7,374 women who had the ENG implant device inserted were included in the study. Mean age of included LNG-IUS users was 31.6±6.3 years compared to 32.1±8.3 years among the excluded. Mean age of ENG implant users was 24.1±6.9 years compared to 24.6±7.4 years among the excluded.

Other data included in this study were year of birth, year of device insertion, type of provider, removal, and whether it was inserted within 8 weeks of childbirth. To determine age at insertion, birth year was subtracted from year of LARC insertion. Provider specialties were categorized and included: obstetricians/ gynecologists (OB/GYNs), pediatricians, family practitioner/ internal medicine/ general practitioners, clinics, non-physician providers, and specialists. The specialist category includes physicians with specialties that do not fit the other categories. In the absence of a code, providers were categorized as “unknown” because it was not known if the provider was a physician or a non-physician provider.

Claims for LNG-IUS or ENG implant insertion within 8 weeks of delivery were examined by age group. Complication claims and removal of the device were examined across the 12 months following device insertion. Claims for complications were only examined until removal of either LARC method. Complications included: pain associated with female genital organs (dyspareunia, dysmenorrhea, or premenstrual tension), disorders of menstruation (excessive menstruation, dysfunctional or functional uterine hemorrhage, postcoital bleeding, endometrial hyperplasia, metrorrhagia, irregular menstrual cycles, absence of menstruation, scanty or infrequent menstruation, or), and inflammation/infection (pelvic inflammatory disease, including inflammatory diseases of the ovary, fallopian tube, pelvic cellular tissue, and peritoneum; and inflammatory disease of the uterus except cervix; cervicitis and endocervicitis; and cystitis). The frequency of normal intrauterine pregnancy and abnormal pregnancy (ectopic pregnancy and molar pregnancy/ abnormal products of conception/ missed or spontaneous abortion) that occurred between device insertion and removal were also examined (ICD-9 codes included in Table 3 footnotes.)

Table 3.

Complications, failure, and discontinuation: ENG implant vs LNG-IUS

| Outcomes | Age 15–19 years | Age 20–24 | Age 25–44 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (column %) | OR (95% CI)c | N (column %) | OR (95% CI)c | N (column %) | OR (95% CI)c | ||||

| ENG implant |

LNG-IUS | ENG implant |

LNG- IUS |

ENG implant |

LNG-IUS | ||||

| Total N | 2,388 | 2,204 | n/a | 2,014 | 8,988 | n/a | 2,972 | 68,728 | n/a |

| Outcomea | |||||||||

| Dysparuniab | 20 (0.8) | 36 (1.6) | 0.51 (0.29, 0.88) | 29 (1.4) | 180 (2.0) | 0.72 (0.48, 1.06) | 45 (1.5) | 821 (1.2) | 1.27 (0.94, 1.72) |

| Dysmenorrhea | 59 (2.5) | 62 (2.8) | 0.88 (0.61, 1.26) | 25 (1.2) | 191 (2.1) | 0.58 (0.38, 0.88) | 44 (1.5) | 1,008 (1.5) | 1.01 (0.75, 1.37) |

| Premenstrual tension | 3 (0.1) | 6 (0.3) | 0.46 (0.12, 1.85) | 5 (0.2) | 36 (0.4) | 0.62 (0.24, 1.58) | 10 (0.3) | 467 (0.7) | 0.49 (0.26, 0.92) |

| Excessive or frequent menstruation | 101 (4.2) | 74 (3.4) | 1.27 (0.94, 1.73) | 80 (4.0) | 233 (2.6) | 1.55 (1.20, 2.01) | 132 (4.4) | 2,561 (3.7) | 1.20 (1.00, 1.44) |

| Dysfunctional or functional uterine hemorrhage | 122 (5.1) | 97 (4.4) | 1.17 (0.89, 1.54) | 92 (4.6) | 343 (3.8) | 1.21 (0.95, 1.53) | 132 (4.4) | 2,494 (3.6) | 1.24 (1.03, 1.48) |

| Postcoital bleeding | 6 (0.3) | 9 (0.4) | 0.61 (0.22, 1.73) | 13 (0.6) | 47 (0.5) | 1.24 (0.67, 2.29) | 8 (0.3) | 209 (0.3) | 0.89 (0.44, 1.80) |

| Endometrial hyperplasia | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.1) | n/a | 0 (0.0) | 5 (0.1) | n/a | 5 (0.2) | 65 (0.1) | 1.78 (0.72–4.42) |

| Metrorrhagia | 68 (2.8) | 36 (1.6) | 1.77 (1.17, 2.66) | 45 (2.2) | 136 (1.5) | 1.49 (1.06, 2.09) | 65 (2.2) | 1,156 (1.7) | 1.31 (1.02, 1.68) |

| Irregular menstrual cycle | 178 (7.5) | 124 (5.6) | 1.35 (1.07, 1.71) | 151 (7.5) | 445 (5.0) | 1.56 (1.29, 1.88) | 165 (5.6) | 3,012 (4.4) | 1.28 (1.09, 1.51) |

| Absence of menstruation | 81 (3.4) | 75 (3.4) | 1.00 (0.72, 1.37) | 58 (2.9) | 261 (2.9) | 0.99 (0.74, 1.32) | 61 (2.1) | 1,277 (1.9) | 1.11 (0.85, 1.44) |

| Scanty or infrequent menstruation | 2 (0.1) | 8 (0.4) | 0.23 (0.05, 1.09) | 7 (0.3) | 26 (0.3) | 1.20 (0.52, 2.77) | 3 (0.1) | 172 (0.3) | 0.40 (0.13, 1.26) |

| Pelvic inflammatory disease | 1 (0.0) | 4 (0.2) | 0.23 (0.03, 2.06) | 1 (0.0) | 14 (0.2) | 0.32 (0.04, 2.42) | 2 (0.1) | 41 (0.1) | 1.13 (0.27, 4.67) |

| Inflammatory disease of the uterus except cervix | 2 (0.1) | 10 (0.5) | 0.18 (0.04, 0.84) | 1 (0.0) | 45 (0.5) | 0.10 (0.01, 0.72) | 3 (0.1) | 188 (0.3) | 0.37 (0.12, 1.15) |

| Cervicitis and endocervicitisb | 30 (1.3) | 45 (2.0) | 0.61 (0.38, 0.97) | 53 (2.6) | 206 (2.3) | 1.15 (0.85, 1.56) | 64 (2.2) | 1,003 (1.5) | 1.49 (1.15, 1.92) |

| Ectopic Pregnancy | 1 (0.0) | 1 (0.0) | 0.92 (0.06, 14.8) | 1 (0.0) | 8 (0.1) | 0.56 (0.07, 4.46) | 0 (0.0) | 36 (0.1) | n/a |

| Abnormal pregnancy or spontaneous abortion | 7 (0.3) | 5 (0.2) | 1.29 (0.41, 4.08) | 10 (0.5) | 20 (0.2) | 2.24 (1.05, 4.79) | 8 (0.3) | 121 (0.2) | 1.53 (0.75, 3.13) |

| Normal pregnancyb | 14 (0.6) | 32 (1.5) | 0.40 (0.21, 0.75) | 18 (0.9) | 118 (1.3) | 0.68 (0.41, 1.12) | 28 (0.9) | 561 (0.8) | 1.16 (0.79, 1.69) |

| Hematoma of upper arm | 0 (0.0) | n/a | 0 (0.0) | n/a | 0 (0.0) | n/a | |||

| Removal within 1 yearb | 295 (12.4) | 257 (11.7) | 1.07 (0.89, 1.28) | 305 (15.1) | 1,152 (12.8) | 1.21 (1.06, 1.39) | 493 (16.6) | 8,102 (11.8) | 1.49 (1.35, 1.64) |

Classification of each complication was determined by the presence of an International Classification of Diseases, 9th revision (ICD-9) corresponding with each complication, including: dysparunia (625.0), dysmenorrhea (625.3), premenstrual tension syndrome (625.4), excessive or frequent menstruation-which also includes menorrhagia and menometrorrhagia (626.2), dysfunctional or functional uterine hemorrhage NOS (626.2), post coital bleeding (626.7), endometrial hyperplasia (621.3, 621.30–621.39), metrorrhagia (626.6), irregular menstrual cycle (626.4), absence of menstruation (626.0), scanty or infrequent menstruation, including oligomenorrhea (626.1), pelvic inflammatory disease (614.0–614.2),inflammatory disease of the uterus except cervix (615, 615.0, 615.1, 615.9), Cervicitis and endocervicitis (616.0), ectopic pregnancy (633.10, 633.11, 633.20, 633.21, 633.80, 633.81, 633.90, 633.91, 761.4), molar pregnancy, abnormal products of conception, missed abortion, spontaneous abortion (630–634, 634.0, 634.00–634.02, 634.1, 634.10–634.12, 634.2, 634.20–634.22, 634.3,634.30, 634.31, 634.4, 634.40–634.42, 634.5, 634.50–634.52, 634.6, 634.60–634.62, 634.7, 634.70–634.72, 634.8, 634.80–634.82, 634.9, 634.90–634.92), normal pregnancy (V22, V22.0, V22.1, V22.2), hematoma of upper arm (23930, 23931), or removal within 1 year (IUD: 97.71, V25.12, V25.13 + Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) code 58301 or 58562, ENG implant: CPT codes 11976, 11982).

Significant interaction of age and contraceptive method were found in Dysparunia, Cervititis/endocervicitis, Normal pregnancy and Removal within 1 year (P values were 0.005, 0.004, 0.01 and 0.002, respectively).

OR (95% CI): Odds ratio (95% confidence interval) of having the specified complication for women with ENG implant vs. those for women with LNG-IUS insertion.

Bolded values indicate significant results (p<0.05).

ENG implant=subdermal etonogestrel implant

LNG-IUS=levonorgestrel intrauterine system

Early discontinuation of LARC (within 12 months of insertion) was examined using ICD-9 or CPT codes for LNG-IUS removal (ICD-9 codes: 97.71, V25.12, V25.13; CPT codes: 58301, 58562) or for ENG implant removal (CPT codes: 11976, 11982). Associations between age, LARC method, and removal of LARC within 30 days of a code indicating abnormal bleeding were also investigated.

Statistical Analyses

Descriptive statistics included (1) the distributions of year of insertion, age, and provider specialty by LARC method and (2) the frequencies of complications, failure, and early discontinuation by age group and LARC method. The ratio of insertion of ENG implants compared to LNG-IUS across time was plotted by age group. Logistic regression models estimated the associations of the type of contraceptive inserted (ENG implant versus LNG-IUS) with age, year of insertion, and physician specialty. Multivariate logistic regression models directly compared outcomes for the ENG implant with LNG-IUS. Each outcome (complication, discontinuation) was coded using a binary response, with 1 indicating that the outcome occurred, and 0 indicating that the outcome was not present. Specifically, the models in this study evaluated the effects of (1) age on the type of contraceptive used within 8 weeks of a delivery, (2) age, type of contraceptive, and their interactive effect on the outcome variables, (3) age group, and (4) the association of abnormal bleeding with discontinuation. Multivariate logistic regression models controlled for age at insertion, contraceptive type, provider type, and year of contraceptive insertions. SAS statistical software version 9.3 (SAS® Institute, Cary, NC) was used to conduct all statistical analyses.

Results

The proportion of total ENG implants that were inserted each year increased greatly from 2007 to 2011 (Table 1). In contrast, the proportion of total LNG-IUSs inserted each year was relatively evenly distributed across each year of study, although the proportion inserted in 2007 was lower than the following years. LNG-IUSs were more frequently placed in women 25 – 44 years of age than women ≤ 24 years of age, while most ENG implants (60%) were placed in women ≤ 24 years of age. Among all provider types, OB/GYNs most frequently inserted either device. The majority of LNG-IUS and ENG implant users did not pay a copay for device insertion (98.2% and 98.7%, respectively.) For those with copays, the mean cost was $28.70 for LNG-IUS and $26.80 for ENG implants (results not shown).

Table 1.

Frequency of subjects in each contraceptive group by year, age, and provider type

| ENG Implant (N=7,374) |

LNG-IUS (N=79,920) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Column % | n | Column % | |

| Year | ||||

| 2007 | 504 | 6.8 | 12,559 | 15.7 |

| 2008 | 1,150 | 15.6 | 18,140 | 22.7 |

| 2009 | 1,330 | 18.0 | 18,007 | 22.5 |

| 2010 | 1,847 | 25.0 | 15,245 | 19.1 |

| 2011 | 2,543 | 34.5 | 15,969 | 20.0 |

| Age (years) | ||||

| 15–19 | 2,388 | 32.4 | 2,204 | 2.8 |

| 20–24 | 2,014 | 27.3 | 8,988 | 11.2 |

| 25–44 | 2,972 | 40.3 | 68,728 | 86.0 |

| Provider Type | ||||

| OB/GYN | 6,386 | 86.6 | 67,502 | 84.5 |

| FP/GP/IM/Pediatrics | 459 | 6.3 | 3,853 | 4.8 |

| Clinics | 55 | 0.7 | 6,083 | 7.6 |

| Non-physician provider | 366 | 5.0 | 1,893 | 2.4 |

| Specialists | 64 | 0.9 | 406 | 0.5 |

| Unknown | 44 | 0.6 | 183 | 0.2 |

ENG implant=subdermal etonogestrel implant

LNG-IUS=levonorgestrel intrauterine system

Among women who had either LARC method inserted within 8 weeks of delivery, 15 – 19 year olds and 20 – 24 year olds were less likely to have an ENG implant inserted than the LNG-IUS (Table 2). The interaction term between age and type of device confirmed that the IUD was preferred by younger women within 8 weeks of delivery while preference for ENG implant contraception within 8 weeks of delivery increased with age.

Table 2.

Frequency and odds of insertion within 8 weeks after delivery in each contraceptive group by age group

| Age in years | ENG implant n (%) |

LNG-IUS n (%) |

OR (95% CI) of ENG implant vs. LNG-IUS |

|---|---|---|---|

| 15–19 | 153 (6.4) | 438 (19.8) | 0.28 (0.23, 0.34) |

| 20–24 | 240 (11.9) | 1803 (20.0) | 0.54 (0.47, 0.62) |

| 25–44 | 415 (13.9) | 9809 (14.3) | 0.98 (0.88, 1.08) |

OR=odds ratio, determined using logistic regression.

95% CI= 95% confidence interval

There is a significant interaction between age and contraceptive insertion (ENG implant vs. LNG-IUS) within 8 weeks after delivery (P<0.001). Younger age is associated with a smaller likelihood of having ENG implant vs. having LNG-IUS inserted within 8 weeks after delivery.

Bolded values indicate significant results (p<0.05).

ENG implant=subdermal etonogestrel implant

LNG-IUS=levonorgestrel intrauterine system

Serious complications among women using either the LNG-IUS or ENG implant were rare, with less than 1% of the women in this study having experienced PID (Table 3). Ectopic pregnancy and molar pregnancy were also rare. ENG implant users from all age groups were more likely to experience metrorrhagia or irregular menstrual cycles within one year of insertion compared to LNG-IUS users. Women who were 20 – 24 years old and 25 – 44 years old were more likely to discontinue the ENG implant within one year of insertion, while there were no significant differences in the likelihood of discontinuing either LARC method in the first year among 15 – 19-year-old women. Overall, normal pregnancies were rare during use of either device. Normal pregnancy occurred in 0.9% of women using LNG-IUS, and 0.8% using ENG implants. The odds for normal pregnancy were lower for 15 – 19-year-old ENG implant users compared to those using the LNG-IUS. The odds of pregnancy were similar for both devices among 20 – 24- and 25 – 44 year-old women. Young ENG implant users (15 – 19 years old) were less likely to experience dysparunia, inflammatory disease of the uterus, or cervicitis compared to those using LNG-IUS. ENG implant users 20 – 24 years of age were less likely to experience dysmenorrhea or inflammatory disease of the uterus compared to those with LNG-IUS. An abnormal pregnancy, although extremely rare for both methods, was twice as likely among ENG implant users as LNG-IUS users only in the 20 – 24 year age group. ENG implant users 25 – 44 years old were more likely to experience excessive menstruation, uterine hemorrhage, cervicitis, or to have the device removed within 1 year. Among LNG-IUS users, early removal more frequently occurred among those that had insertions in clinics (18.7%) and by specialists (16.3%) followed by OB/GYNs (11.3%), general practitioners (11.2%), and non-physician providers (10.7%). Early discontinuation of ENG implants occurred more frequently among those that had their device inserted in a clinic (16.4%) or by OB/GYNs (15.2%) followed by non-physician providers (12.6%), general practitioners (12.6%), and specialists (12.5%).

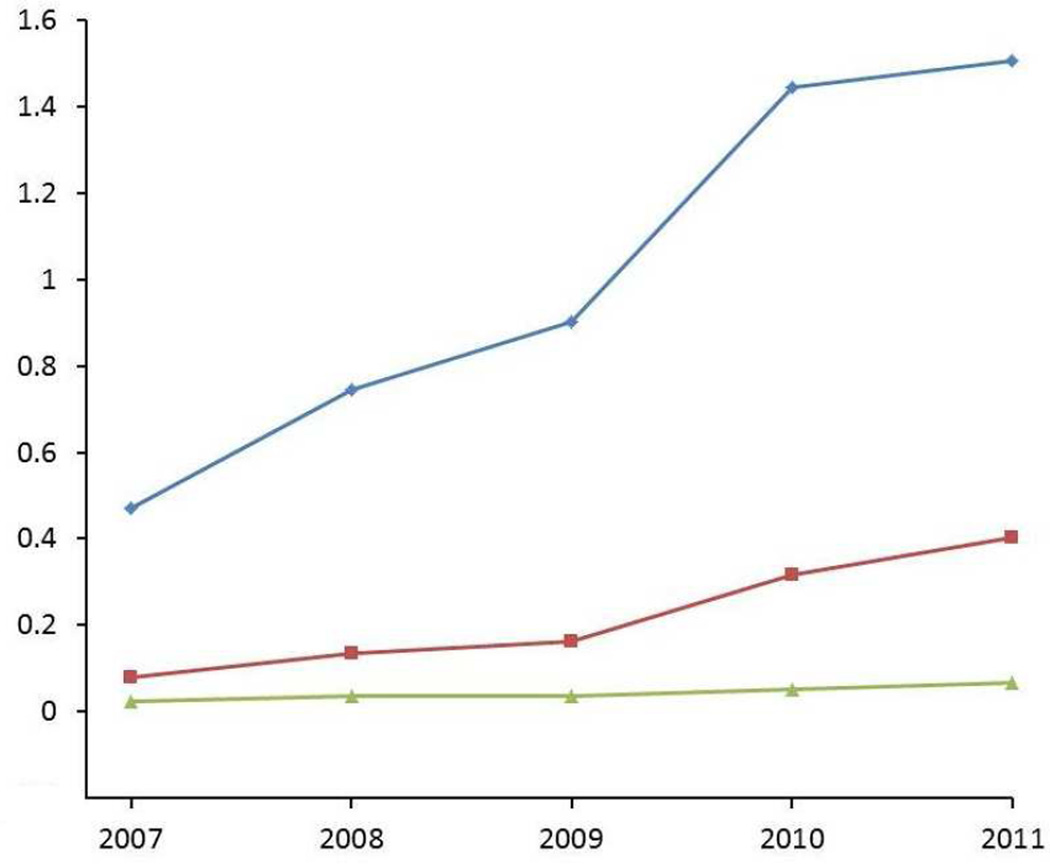

Women who used ENG implants were more likely to have the devices removed within 30 days of visiting their doctor after reporting abnormal bleeding (Table 4). Over time, the youngest age group had the highest increase in the ratio of ENG implant to LNG-IUS insertion (Figure 1). While this ratio grew in teenagers during each subsequent year of observation, women in the two older age groups chose the LNG-IUS over the ENG implant. This ratio remained steady across time among the 25 – 44-year-old women until 2009, when 20 – 24-year-old women began to choose ENG implants more frequently (although the ratio never approached 1). To determine whether preexisting menstrual problems may have been related to the observed differences in insertion rates, we examined the proportion of 25 – 44-year-old women that reported excessive/frequent menstruation, uterine hemorrhage, or metrorrhagia 30 days before insertion. We found that 3% of 25 – 44-year-old women who received the LNG-IUS reported excessive/frequent menstruation compared to 1.5% of ENG implant users (results not shown). The proportion of 25 – 44-year-old women with claims for other types of menstrual problems were similar between LNG-IUS and ENG implant users.

Table 4.

Removal within 30 days after abnormal bleeding, ENG implant compared to LNG-IUS

| Age (years) | ENG implant | LNG-IUS | OR (95% CI) of Removal with 30days, ENG implant vs. LNG-IUS |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n with abnormal bleeding |

% Removed within 30 days after abnormal bleeding |

n with abnormal bleeding |

% Removed within 30 days after abnormal bleeding |

||

| 15–19 | 406 | 27.6 | 295 | 19.7 | 1.56 (1.09, 2.23) |

| 20–24 | 324 | 28.7 | 1043 | 21.4 | 1.48 (1.12, 1.96) |

| 25–44 | 402 | 31.3 | 8012 | 21.9 | 1.63 (1.31, 2.02) |

There was no significant interaction between age and contraceptive method in removal within 30 days after abnormal bleeding (P=0.87).

Bolded values indicate significant results (p<0.05).

ENG implant=subdermal etonogestrel implant

LNG-IUS=levonorgestrel intrauterine system

Figure 1. Rate ratio of ENG implant insertion compared to LNG-IUS insertion in 2007–2011, by age group.

Figure 1 descriptive sentence: Trends in the insertion rates of the ENG implant compared to LNG-IUS across time for 15 – 19 year olds, 20–24 year olds, and 25–44 year olds.

Age

15–19

15–19  20–24

20–24  25–40

25–40

Comment

For the 4-year interval following its introduction (2007–2011), the frequency of ENG implant insertions increased five-fold. Almost one-third of the implants were inserted in teens, illustrating good acceptance of this method among physicians for younger patients. In comparison, IUD use failed to increase over the observed period and was infrequently prescribed to women less than 20 years of age. Among women ≤ 24 years old who obtained one of these methods within 8 weeks of delivery, the LNG-IUS was more popular than ENG implants, suggesting that barriers to obtaining an IUD decrease for young women after childbirth. The stable rate of IUD insertion from 2007–2011 and its infrequent use in young women highlight the need to offer further education to both physicians and patients on the safety of prescribing modern IUDs to nulliparous women. Furthermore, providers should be informed that 88% of teenage LNG-IUS and ENG implant users in our sample continued to use their selected method for at least 12 months.

With regards to complications, 15–19-year-old women who used the ENG implant were less likely to experience dyspareunia, endometritis, cervicitis, and normal pregnancy compared to LNG-IUS users. Lower odds of experiencing cervicitis in this group could be due to selection biases, as many providers do not routinely recommend the LNG-IUS to women with a history of sexually transmitted infections.14 ENG implant users 20 – 24 years of age were less likely to experience inflammatory disease of the uterus and those >24 years of age were more likely to be diagnosed with cervicitis. Due to the nature of our study, we could not determine the exact cause of these complaints. In addition, some of the differences observed may be due to chance, since the frequency of these events is very rare. However, our data do show that the percentage of women in each age group diagnosed with one of these complications while using either LARC method is low.

Overall, women using either LARC method in our study experienced abnormal bleeding patterns, pain, and other complications at similar or lower rates than detected in clinical trials.15–18 In particular, the frequencies for absent or infrequent menstruation for both LARC methods were nearly 10-fold lower than previously reported frequencies.15,16 These lower complication rates in our study are probably due to use of claims data which includes only problems that are reported to and coded by a provider in contrast to clinical trial data which encompasses all complications.

ENG implant users in all 3 age groups had a higher risk of menstrual problems compared to IUD users and were more likely to discontinue their method prematurely after abnormal bleeding was reported. Prior studies also observed that abnormal menstrual bleeding is a common reason for early discontinuation of ENG implants.2,19 Abnormal menstrual bleeding may also have been the reason that ENG implant users over age 19 were more likely than IUD users to discontinue their method within 1 year. To avoid early discontinuation, it has been suggested that patients requesting contraceptive implants receive counseling regarding the likelihood of abnormal bleeding before the device is implanted,20 and offer treatment, such as tranexamic acid, mifepristone combined with an estrogen, and doxycycline, if abnormal bleeding does occur.21

This study had several limitations. First, we used administrative claims data which were intended for billing purposes and did not have access to certain information, such as gravidity, parity, and other factors that may have affected choice of contraception type. The use of claims data may have resulted in an underreporting of minor complications, which may not have been reported by the patient or coded by the healthcare provider. However, it is unlikely that underreporting occurred more often among patients using one of the two LARC methods evaluated (except perhaps for removal of the ENG implant, as that is more provider dependent), so our study still provides important comparative information about these two LARC methods. Using this national database allows information to be collected on a large sample of the general population. Nonetheless, these data were limited to women who had private insurance and thus may not be generalizable to women of low socioeconomic status. Additionally, it was not always possible to determine whether a pregnancy in the LNG-IUS group occurred as a result of spontaneous expulsion of the device. Miscoding or lack of coding for spontaneous expulsion may have also caused an underestimate of early discontinuation of LNG-IUS. Finally, reasons for early discontinuation could not be determined from the data available and study diagnoses could not be confirmed because charts were not available. This is particularly important when considering pregnancy as an outcome, as this condition could not be confirmed.

We found that both methods were well tolerated among women of all ages with few side effects and that continuation rates exceeded those observed with other contraceptive methods.12,22 Results from this direct comparison will help healthcare providers better counsel their patients about the benefits of both types of LARC as well as help patients choose which method best fulfills their needs.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Dr. Hirth is a Scholar supported by a research career development award (K12HD052023: Building Interdisciplinary Research Careers in Women’s Health Program –BIRCWH; Principal Investigator: Berenson) from the Office of Research on Women’s Health (ORWH), the Office of the Director (OD), the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) at the National Institutes of Health. This study was supported by the Institute for Translational Sciences at the University of Texas Medical Branch, which is partially funded by a Clinical and Translational Science Award (UL1TR000071). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

The authors report no conflict of interest.

These findings were presented at the 2014 North American Forum on Family Planning. This meeting was produced jointly by Planned Parenthood Federation of America and the Society of Family Planning in Miami, FL, on October 12th–13th, 2014.

Contributor Information

Abbey B. Berenson, Obstetrics and Gynecology, Director, Center for Interdisciplinary Research in Women’s Health, The University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston.

Alai Tan, Institute for Translational Sciences, The University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston.

Jacqueline M. Hirth, Obstetrics and Gynecology, The University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston.

References

- 1.Finer LB, Zolna MR. Shifts in intended and unintended pregnancies in the United States, 2001–2008. American Journal of Public Health. 2014;104(S1):S43–S48. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Power J, French R, Cowan F. Subdermal implantable contraceptives versus other forms of reversible contraceptives or other implants as effective methods for preventing pregnancy. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2008 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001326.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Trussell J. Contraceptive failure in the United States. Contraception. 2011;83:397–404. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2011.01.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Whitaker AK, Sisco KM, Tomlinson AN, Dude AM, Martins SL. Use of the intrauterine device among adolescent and young adult women in the United States from 2002 to 2010. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2013;53:401–406. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Finer LB, Jerman J, Kavanaugh ML. Changes in use of long-acting contraceptive methods in the United States, 2007–2009. Fertility and Sterility. 2012;98(4):893–897. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2012.06.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grunloh DS, Casner T, Secura GM, Peipert JF, Madden T. Characteristics associated with discontinuation of long-acting reversible contraception within the first 6 months of use. Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2013;122(6):1214–1221. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000435452.86108.59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Adolescents and long-acting reversible contraception: implants and intrauterine devices. Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2012;539:983–988. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3182723b7d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tyler CP, Whiteman MK, Zapata LB, Curtis KM, Hillis SD, Marchbanks PA. Health care provider attitudes and practices related to intrauterine devices for nulliparous women. Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2012;119(4):762–771. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31824aca39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Berenson AB, Tan A, Hirth JM, Wilkinson GS. Complications and continuation of intrauterine device use among commercially insured teenagers. Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2013;121:951–958. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31828b63a0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carr S, Espey E. Intrauterine devices and pelvic inflammatory disease among adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2013;52:S22–S28. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rosenstock JR, Peipert JF, Madden T, Zhao Q, Secura GM. Continuation of reversible contraception in teenagers and young women. Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2012;120(6):1298–1305. doi: 10.1097/aog.0b013e31827499bd. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.O'Neil-Callahan M, Peipert JF, Zhao Q, Madden T, Secura G. Twenty-four-month continuation of reversible contraception. Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2013;122(5):1083–1091. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3182a91f45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Peipert JF, Zhao Q, Allsworth JE, et al. Continuation and satisfaction of reversible contraception. Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2011;117(5):1105–1113. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31821188ad. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Callegari LS, Darney BG, Godfrey EM, et al. Evidence-based selection of candidates for the Levonorgestrel intrauterine device (IUD) Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine. 2014;27:26–33. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2014.01.130142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jensen JT, Nelson AL, Costales AC. Subject and clinician experience with the levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system. Contraception. 2008;77(1):22–29. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2007.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Darney P, Patel A, Rosen K, Shapiro LS, Kaunitz AM. Safety and efficacy of a single-rod etonogestrel implant (Implanon): results from 11 international clinical trials. Fertility and Steriity. 2009;91(5):1646–1653. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.02.140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nelson A, Apter D, Hauck B, Schmelter T, Rybowski S, Rosen K, Gemzell-Danielsson K. Two low-dose levonorgestrel intrauterine contraceptive systems: a randomized controlled trial. Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2013;122(6):1205–1213. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000000019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Funk S, Miller MM, Mishell DR, Jr, Archer DF, Poindexter A, Schmidt J, Zampaglione E Implanon US Study Group. Safety and efficacy of Implanon, a single-rod implantable contraceptive containing etonogestrel. Contraception. 2005;71(5):319–326. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2004.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wong RC, Bell RJ, Thunuguntla K, McNamee K, Bollenhoven B. Implanon users are less likely to be satisfied with their contraception after 6 months than IUD users. Contraception. 2009;80:452–456. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2009.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mansour D, Korver T, Marintcheva-Petrova M, Fraser IS. The effects of Implanon on menstrual bleeding patterns. The European Journal of Contraception and Reproductive Health Care. 2008;13(S1):13–28. doi: 10.1080/13625180801959931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Abdel-Aleem H, d’Arcangues C, Vogelsong KM, Gaffield ML, Gulmezoglu AM. Treatment of vaginal bleeding irregularities induced by progestin only contraceptives. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2013;10 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003449.pub5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nelson AL, Westhoff C, Schnare SM. Real-world patterns of prescription refills for branded hormonal contraceptives. Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2008;112(4):782–787. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181875ec5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.