Abstract

Background

The majority of individuals with schizophrenia and other psychotic illnesses have had suicidal ideation at some point during the illness. However, little is known about the variation in level and intensity of suicidal ideation and symptoms in the attenuated stage of psychotic illness. Our aims were to assess prevalence of suicidal ideation in this at risk group, and to examine the severity and intensity of suicidal ideation, and their relation to symptoms.

Methods

Suicidal ideation was assessed in 42 clinical high-risk participants using the Columbia Suicide Severity Rating Scale (C-SSRS). We hypothesized prevalence rates would be similar to what was found in previous studies, and individuals with suicidal ideation would have higher positive and negative symptoms, with poorer functioning. We assessed levels of severity and intensity of suicidal ideation related to these symptoms, and examined how depressive symptoms affected these relationships.

Results

Nearly half (42.9%) of participants reported having current suicidal ideation. We found no relationship to positive symptoms. However, severity and intensity of suicidal ideation was found to be related to negative symptoms and level of functioning. When controlling for depressive symptoms during exploratory analysis, this relationship still emerged.

Conclusions

This study adds to the literature demonstrating the complex nature of suicidal ideation in psychotic illness. The C-SSRS has shown to be helpful in determining relationships between severity and intensity in suicidal ideation in relation to specific symptoms in a research setting.

Keywords: suicidal ideation, schizophrenia, clinical high risk, psychosis, functioning

1. Introduction

The majority of individuals with schizophrenia (40–79%) have had suicidal ideation (SI) at least some time during their course of illness (Fenton et al., 1997; Skodlar et al., 2008), a finding which holds across gender and ethnicity (Harkavy-Friedman et al., 1999). Identified correlates of SI in this population have included mood variability, negative symptoms, and depressive symptoms (Fialko et. al., 2006; Hocaoglu and Babuc, 2009; Jovanovic et al., 2013; Kontaxakis et al., 2004; Palmier-Claus et al., 2013), as well as positive symptoms (Taylor et al., 2010). We have previously examined the prevalence of SI in young people at clinical high-risk for psychosis (CHR), finding that 55% reported having suicidal thoughts (DeVylder et al., 2012), a prevalence replicated in other cohorts (Hutton et al., 2011). Given this prevalence in CHR, it is important to examine how symptoms may affect SI in the attenuated stage of psychotic illness.

A retrospective study of SI during the prodromal phase among individuals with schizophrenia by Andriopoulos and colleagues (2011) found that individuals with SI had greater total negative and positive symptoms than did individuals without SI (Andriopoulos et al., 2011). In addition, they reported that depressive mood and marked impairment in role functioning were independent predictors of SI. Of note, the retrospective design of this study may influence inaccurate reporting or recall bias. A recent meta-analysis by Taylor and colleagues (2014) described additional associations of SI with symptoms and functioning, such as obsessive-compulsive symptoms, poorer role and social functioning, and health. Additionally, Preti et al. (2009) found that as symptoms severity decreased in CHR groups, suicidality also decreased.

In an effort to better understand SI in CHR subjects, we used the Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale (C-SSRS, Posner et al., 2011), which specifically probes parasuicidal ideation (wish to be dead, without intent or plan), the nature (intent and plan), and intensity (frequency, duration, controllability, potential deterrents, reasons) of suicidal ideation, as well as the nature of any suicide attempts (and if interrupted, aborted, or preparatory). Our aim was to better characterize SI in CHR patients, and evaluate its association with symptoms and functioning. The C-SSRS is ideally suited to this type of investigation given that it assesses SI over a spectrum, rather than as a dichotomous measure.

We hypothesized that prevalence rates of SI in a CHR adolescent cohort would be similar to those reported in the literatures on schizophrenia (Fenton et al., 1997; Skodlar et al., 2008) and attenuated psychosis CHR cohorts (including a sample from the same cohort as the current study; DeVylder et al., 2012; Hutton et al., 2011). We compared symptoms between groups of individuals who had SI within the past six months and those who did not, predicting that individuals with recent SI would have higher total positive and negative symptoms, as previously reported (Andriopoulos et al., 2011). Also based upon Andriopoulos and colleagues’ findings, we further hypothesized that those individuals with recent SI would have poorer functioning, particularly role deficits. We then examined the levels of severity and the intensity of SI as measured by the C-SSRS in relation to the previously mentioned positive symptoms, negative symptoms and functioning in this CHR group.

Given that negative symptoms commonly overlap with depressive symptoms, and that poor functioning can be related to depression, our aim is to distinguish whether or not the relationship found between SI and negative symptoms and functioning is due to depression levels in these CHR participants. We also sought to descriptively present the spectrum of SI in the CHR period using the C-SSRS which, rather than measuring SI as a dichotomous index, provides a more finely grained picture of the spectrum of SI. Finally, exploratory analyses were performed to determine whether SI is present in CHR individuals outside the context of depression.

2. Methods

2.1 Participants

A cohort of 42 help-seeking individuals at CHR for psychosis was ascertained using the Structured Interview for Prodromal Syndromes (SIPS, Miller et al., 2003). Participants were recruited to the Center of Prevention and Evaluation (COPE) from the New York City metropolitan area using the Internet (i.e., Craigslist), fliers, and letters/presentations to academic counseling centers and clinicians. Most CHR individuals were ascertained through referrals from schools and clinicians. Participants in this sample were collected from July 2012 through November 2013, and met with a clinical psychologist (GB) for an evaluation of high risk status. CHR participants were enrolled on the basis of meeting criteria for at least one of the following psychosis risk syndromes, as defined by the SIPS: 1) Attenuated Positive Symptom (APS) Psychosis-Risk Syndrome; 2) Genetic Risk and Deterioration (GRD) Psychosis-Risk Syndrome; and/or 3) Brief Intermittent Psychotic Symptom (BIPS) Psychosis-Risk Syndrome (Miller et al., 2003). Exclusion criteria included attenuated positive symptoms occurring solely in the context of substance use or better accounted for by a non-psychotic condition, a history of threshold psychosis, IQ < 70, medical or neurological disorders, and a serious risk of harm to self or others. Longitudinal assessment of transition to psychosis was reassessed every 3 months using the SIPS/SOPS, with a target length of follow-up of 2.5 years. Of note, healthy controls were excluded from this study if they were to report any instance of SI, so that no control group for the present study was possible.

The sample was assessed at baseline for demographics, symptomology, and social and role functioning, in addition to the suicide assessment. SI was also measured at follow-up appointments. Individuals who endorsed significant risk for suicide during the interview were evaluated and given clinical treatment.

2.2 Symptoms and Functioning

The SIPS (Miller et al., 2003) assesses “prodromal” symptoms in four categories: positive, negative, disorganized, and general symptoms. Each item is scored on a range of 0–6, with a score on positive symptoms of 3–5 occurring at an average frequency of at least once per week over one month considered “prodromal”. Positive symptoms include: unusual thought content, suspiciousness, grandiosity, perceptual disturbances, and disorganized communication. The negative symptoms include: social anhedonia, avolition, decreased expression of emotion, decreased experience of emotions and self, lack of ideational richness, and occupational decline. We focused on the total positive and total negative symptoms from this assessment. Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF) scores were also assessed using this instrument.

The Global Functioning Scale: Role (GFS: Role; Niendam et al., 2006) assesses age-appropriate performance at school, home or work. A score is given by assessing the demands of the role one is in and the level of support the individual receives. The Global Functioning Scale: Social (GFS: Social; Auther et al., 2006) assesses peer relationships based on age-appropriate social contacts inside and outside the family, romantic relationships, as well as the level of conflict the individual may or may not experience in these relationships. These scores are based on a 1–10 scale, similar to the traditional GAF scale, with 10 being highly functioning in one’s role, and 1 being low/no functioning.

For our exploratory analyses, we examined depressive symptoms using the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI; Beck et al., 1961), which was collected at the same time as the C-SSRS. The BDI is a 21-item self-report tool that measures the severity of depression. Each response is assigned a value of 0 to 3, with higher numbers indicating greater severity of the depressive symptom.

2.3 Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale (C-SSRS)

The C-SSRS (Posner et al., 2011) has multiple versions, including a “Screener” version, a “Lifetime/Recent” version (typically measured at baseline assessment), and a “Since Last Visit” version (typically measured at follow-up assessments). The C-SSRS has four constructs relevant to recent SI: 1) severity (1=wish to be dead, 2=nonspecific active suicidal thoughts, 3=suicidal thoughts with methods, 4=suicidal intent, and 5=suicidal intent with plan); 2) intensity (sum across six items each rated 0 to 5: most severe ideation, frequency, duration, controllability, deterrents, and reason); 3) behavior; and 4) lethality. The sum score for intensity was used as the six items in this construct, which were independent and not correlated. No CHR participant endorsed current suicidal behavior or lethality, so as a result, analyses focused only on severity and intensity of SI. Both the C-SSRS “Lifetime/Recent” version and the “Since Last Visit” version were used with this sample. The “Lifetime/Recent” version was collected at baseline, and provides information on lifetime history of suicidality, as well as any recent suicidal ideation and/or behavior (e.g. within the past six months). The “Since Last Visit” version provides information on suicidal ideation occurring since the last visit (typically 3 months). Reports of recent SI using the “Lifetime/Recent” version were used for newer participants who had not yet completed a follow-up C-SSRS. Reports of recent SI determined by the “Since Last Visit” version were used for participants who had completed follow-up assessments. The use of both assessments was to ensure the most recent report of SI for each participant was being examined (within the past 3–6 months). Reports of lifetime SI were examined solely for descriptive analysis.

2.4 Data analysis

Descriptive statistics for participants with SI (CHR+SI) and without SI (CHR-SI) were run. Chi-square analyses were used to evaluate proportions across the participants with SI and those without in terms of gender and ethnicity; and t-tests were conducted for comparison of age. Descriptive statistics were also used to determine prevalence of lifetime SI and to describe the degree of current SI (as measured by severity and intensity) in the CHR+SI group. Between the two groups (CHR+SI; CHR-SI), t-tests were used to compare the positive symptoms, negative symptoms, and functioning as measured by the GAF and GFS role and social scales. Severity and intensity measures were compared with symptoms and functioning using Spearman correlations with the alpha level set at .05. Partial Spearman correlational analyses were run to measure the relationship between SI and symptoms and functioning while controlling for depressive symptoms.

3. Results

There were 42 CHR participants, who were primarily male (71%), ethnically diverse (45% Caucasian), and ranged in age from 13 to 27 (M = 20.3, SD = 3.8). Of these participants, 57% reported taking psychoactive medication (either antidepressants, antipsychotics, or both). There were no significant differences in age, gender, race, or medication between CHR+SI and CHR-SI groups (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographics and Clinical Characteristics

| Demographics | CHR + SI (n=18) | CHR − SI (n=24) |

|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD) | 20.4 (3.4) | 20.2 (4.1) |

| Gender (%male) | 61.1 | 79.2 |

| Race (%Caucasian) | 55.6 | 37.5 |

| Ethnicity (%Hispanic) | 29.4 (N=17) | 25.0 (N=20) |

| Medication (% prescribed) | 52.9 (N=17) | 35.0 (N=20) |

| Clinical Characteristics, mean (SD) | ||

| Total Positive Symptoms | 13.88 (4.01) | 13.27 (4.18) |

| Total Negative Symptoms* | 19.59 (6.16) | 14.55 (6.13) |

| GAF* | 43.82 (6.47) | 50.38 (7.62) |

| GFS: Role | 5.17 (2.07) | 6.10 (1.71) |

| GFS: Social | 5.28 (1.32) | 5.90 (1.33) |

| BDI** | 16.06 (9.64) | 5.25 (4.00) |

p<05

p<01

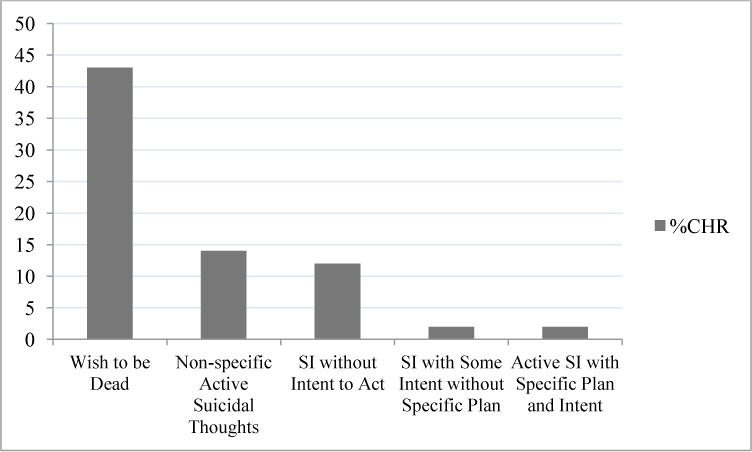

Of the individuals who were assessed for lifetime (n=30) SI, 23 CHR participants reported having SI at some point in their lives (76.7%). In the most recent assessment of SI (within the past 3–6 months), less than half (42.9%) reported having current SI. We present, in Figure 1, the differing severity levels of current SI (from least severe to most severe) in CHR as measured by the C-SSRS which shows that less severe, parasuicidal ideation is the most prevalent level of SI. SI intensity (which ranges from 0–30) was examined, and the highest level of ideation reported was 17 (M=11.11, SD=3.94). This falls relatively on the low end of the intensity scale, suggesting that the parasuicidal ideation in this CHR group is of relatively low intensity.

Figure 1.

Severity of Suicidal Ideation (SI) in Clinical High Risk (CHR) Individuals

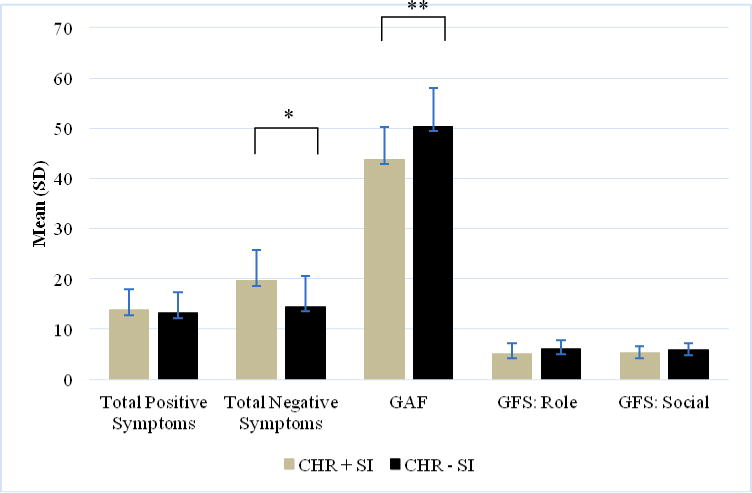

Symptoms and functioning assessment between the two groups (CHR+SI, CHR-SI; n=42) yielded significant differences in total negative symptoms (p=0.018), and GAF (p=0.008), but not in total positive symptoms, role or social functioning (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Symptoms and Functioning in Clinical High Risk (CHR) Individuals with and without Suicidal Ideation (SI)

*p<.05

**p<.01

Using the severity and intensity scales, we found no relationship to positive symptoms. There was, however, a strong relationship of the level of severity of SI to total negative symptoms (r= .49, p=0.002) and functioning (as measured by the GAF; r= −.48, p=0.002).). There was a trend-level relationship between severity of suicidal ideation and role functioning (r= −.31, p=0.06). We found similar results with the intensity scale; there was no relationship with positive symptoms, but there was a relationship with total negative symptoms (r= .50, p=0.002) and functioning (r= −.54, p<0.001). We found no relationship between intensity of ideation to role or social functioning. Of note, the relationship between GAF and C-SSRS scores is expected, given that the presence of suicidality is considered when scoring the GAF. In addition, these results survived correction for multiple comparisons.

To determine if the association between recent SI and negative symptom severity might be confounded or explained by the association of each with depressive symptoms, we conducted a partial correlation analysis that included recent SI, negative symptoms and depressive symptoms. Depressive symptoms were correlated with negative symptoms (p=0.01), functioning (p=0.006), severity of SI (p=0.004), and intensity of SI (p<0.001). When adjusting for depressive symptoms, negative symptoms remained significantly (albeit less) correlated with both severity (r=0.38, p=0.02) and intensity (r=0.34, p=0.04) of recent SI. A similar analysis for mGAF scores yielded a significant (albeit reduced) correlation of mGAF with severity (r= −0.34, p=0.04) and intensity (r= −0.38, p=0.03) of recent SI.

4. Discussion

Suicidal ideation among CHR youths has been reportedly as high as 58.8% at the time of assessment (Hutton et al., 2011), which is comparable to the 42.9% prevalence in the current study. Additionally, 76.7% of CHR individuals had SI at some point in their lifetime, similar to what was found in a recent meta-analysis of SI in CHR by Taylor and colleagues (2014). This is the first study to examine SI in a CHR cohort using the C-SSRS assessment. This study demonstrates that CHR patients with suicidality experience greater severity of total negative symptoms and worse functioning than those without suicidal behavior, and that controlling for depressive symptoms does not substantially diminish the relationship. This relationship is similar to a study examining the relationship between depressive and negative symptoms in the same CHR cohort (Corcoran et al., 2011), showing that both depressive symptoms and negative symptoms were related to social impairment, but when considered together, the negative symptoms drove the association. In addition, while the CHR+SI group had significantly higher negative symptoms than the CHR-SI group, the two groups were similar in regard to positive symptoms. Demjaha and colleagues (2012) found that negative symptoms were associated with subsequent transition to psychosis, consistent with a report that in in familial high risk individuals, a set of attenuated negative and disorganization symptoms, in combination with social deficits, preceded the onset of schizophrenia (Cornblatt, 2002). Together, these findings suggest the importance of differentiating between depressive symptoms and negative symptoms, particularly for determining risk of conversion to psychosis and in treatment planning. As SI is primarily manifest in our CHR cohort as a passive wish to be dead and this is related to negative symptoms, it may be important to include assessment of passive SI when determining level of negative symptoms in CHR and possible transition to psychosis.

Depressive mood is not uncommon in CHR patients, (Yung et al. 2004), making it important to consider when assessing suicidality. The BDI is often used to assess SI, but does not differentiate between intensity and severity as the C-SSRS does. Previous studies have criticized the BDI for having low predictive power, thereby bringing into question the lack of specificity this measure has in terms of predicting SI (Caldwell and Gottesman, 1990). In the current cohort, only 21.4% of group responded above 0 on the BDI suicide item (with scores >0=SI), whereas 42.9% reported SI on C-SSRS. This suggests the usefulness of the C-SSRS as both a research tool and a safety measure in research protocols.

The ability to determine varying levels of suicide severity and intensity using the C-SSRS, in concordance with additional symptoms, may assist clinicians in determining appropriate treatment planning for CHR individuals. The largely passive suicidal ideation we have described in CHR individuals, and its association with negative symptoms, has important ramifications for clinical assessment. A simple query as to whether CHR individuals have suicidal thoughts or not, as is done with the Beck Depression Inventory, may not capture their possible wish to be dead or their ideation without plan or intent, which nonetheless reflects current functional impairment. This may become more severe and dangerous later, as suicidal ideation at baseline has been shown to predict suicide attempt later in first-episode schizophrenia patients (Sanchez-Gistau et al., 2013; Bertelsen et al., 2007). The presence of negative symptoms in CHR individuals, and possibly in patients with schizophrenia as well (Hocaoglu and Babuc, 2009), should prompt questions as to less severe, more passive suicidal ideation. Likewise, a report of passive suicidal ideation, or expressed wish to be dead, in CHR individuals should lead to a careful assessment of negative symptoms and functional impairment. As suggested by Pompili (2010), it is important to consider the underlying pain of negative emotions that may drive suicidal ideation and behavior. Our study also adds to the extant literature that highlights negative symptoms as important features of clinical risk for psychosis (Demjaha et al., 2012) that account for functional impairment, even independent of depressive symptoms (Corcoran et al., 2011).

Comparing levels of suicidality among CHR individuals with those who have already developed a psychotic disorder, such as schizophrenia, may elucidate when and why these suicidal thoughts and/or behaviors manifest. In one study (Preti et al., 2009), individuals experiencing a first episode of psychosis (FEP) were compared with individuals meeting CHR criteria with regard to levels of SI and behavior, which yielded results implying that these two groups had equal levels of ideation and behavior. Longitudinal research is needed to more thoroughly investigate and better clarify the complex issue of suicide in the various stages of psychosis. In a review of suicide risk in FEP (Pompili et al., 2011), the authors concluded that one of the greatest challenges of properly carrying out this type of longitudinal research is the lack of comprehensive examinations of both risk factors and fatal, as well as non-fatal suicidal acts.

There are a number of limitations in this first detailed study of suicidal ideation in CHR individuals, including its small size, the lack of comparison subjects, and its cross-sectional nature. While the CSSR-S appears to have utility in a CHR cohort, this must be replicated in a second and larger sample. Also, although our prodromal research program has healthy comparison subjects, suicidal ideation is an exclusion criterion for these healthy controls, such that they could not be included in the current analyses of suicidal ideation. Related to this, the true prevalence of suicidal ideation in CHR individuals may be underestimated in the current study, as serious risk of harm to self is an exclusion criterion for patients in our CHR cohort. Future studies could include comparisons with community samples of adolescents and young adults, as well as “patient” controls who have non-psychotic illnesses such as depression or anxiety. Longitudinal studies of first episode psychosis cohorts (Sanchez-Gistau et al., 2013; Bertelsen et al., 2007) have been informative as to how suicidal ideation and behavior evolve over time, related to integrated treatment, and similar longitudinal studies should have utility in CHR cohorts, including its relationship to psychosis transition and eventual functional outcome.

In summary, this study adds to the growing literature demonstrating the complex nature of SI in a CHR group, although these findings may also translate to other clinical adolescent groups as well. With the use of the C-SSRS, more research can be directed towards carefully monitoring these levels of severity and intensity in SI, and facilitating the knowledge of their relationships to specific symptoms, which can help create safety plans for adolescents with SI.

Table 2.

Severity and Intensity of SI Correlated with Symptoms and Functioning

| Spearman ‘r’ Correlations | Total Positive Symptoms | Total Negative Symptoms | GAF | GFS: Role | GFS: Social |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Severity Scale | 0.06 | 0.49* | −0.48* | −0.31 | 0.20 |

| Intensity Scale | 0.03 | 0.50* | −0.54** | −0.26 | 0.16 |

p<0.01

p<0.001

Acknowledgments

None

Role of the Funding Source

The project described was supported by the National Institute of Health: 1) Center for Research Resources and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, UL1 TR000040 and 2KL2RR024157; R01 MH093398-01, 2) the Lieber Center for Schizophrenia Research and 3) New York State Office of Mental Hygiene.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributors

All authors contributed to the study design and/or writing the protocol. Author KEG managed the literature searches and analyses. Author CMC developed and initiated the study, collected data through the end of 2012, and worked closely with KEG in preparation of the manuscript, both in its initial preparation and then in editing successive draft. Authors KEG and RRG undertook the statistical analysis. All authors contributed to interpreting the analyses. Author KEG wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors contributed to and have approved the final manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

Ragy R. Girgis declares research support from Otsuka and Genentech. All other authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- Andriopoulos I, Ellul J, Skokou M, Beratis S. Suicidality in the “prodromal” phase of schizophrenia. Comp Psychiat. 2011;52(5):479–485. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2010.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auther A, Smith C, Cornblatt B. Global Functioning Scale: Social (GFS: Social) Zucker Hillside Hospital; Glen Oaks, NY: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Ward CH, Mendelson J, Mock J, Erbaugh J. An inventory for measuring depression. Arch Gen Psychiat. 1961;4:53–63. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1961.01710120031004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertelsen M, Jeppesen PIA, Petersen L, Thorup A, Øhlenschlaeger J, le Quach P, Christensen TØ, Krarup G, Jørgensen P, Nordentoft M. Suicidal behaviour and mortality in first-episode psychosis: the OPUS trial. Br J Psychiatry. 2007;191(51):s140–s146. doi: 10.1192/bjp.191.51.s140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caldwell CB, Gottesman I. Schizophrenics kill themselves too. Schizophrenia Bull. 1990;16:571–586. doi: 10.1093/schbul/16.4.571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corcoran CM, Kimhy D, Parrilla-Escobar MA, Cressman VL, Stanford AD, Thompson J, Malaspina D. The relationship of social function to depressive and negative symptoms in individuals at clinical high risk for psychosis. Psychol Med. 2011;41(02):251–261. doi: 10.1017/S0033291710000802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornblatt BA. The New York high risk project to the Hillside recognition and prevention (RAP) program. Am J Med Genet. 2002;114(8):956–966. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.10520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demjaha A, Valmaggia L, Stahl D, Byrne M, McGuire P. Disorganization/cognitive and negative symptom dimensions in the at-risk mental state predict subsequent transition to psychosis. Schizophr Bull. 2012;38(2):351–359. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbq088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeVylder JE, Oh A, Ben-David S, Azimov N, Harkavy-Friedman J, Corcoran CM. Obsessive compulsive symptoms in individuals at clinical risk for psychosis: association with depressive symptoms and suicidal ideation. Schizophr Res. 2012;140(1–3):110–113. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2012.07.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fenton WS, McGlashan TH, Victor BJ, Blyler CR. Symptoms, subtype, and suicidality in patients with schizophrenia spectrum disorders. Am J Psychiat. 1997;154(2):199–204. doi: 10.1176/ajp.154.2.199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fialko L, Freeman D, Bebbington PE, Kuipers E, Garety PA, Dunn G, Fowler D. Understanding suicidal ideation in psychosis: findings from the Psychological Prevention of Relapse in Psychosis (PRP) trial. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2006;114(3):177–186. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2006.00849.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harkavy-Friedman JM, Restifo K, Malaspina D, Kaufmann CA, Amador XF, Yale SA, Gorman JM. Suicidal behavior in schizophrenia: characteristics of individuals who had and had not committed suicide. Am J Psychiat. 1999;156:1276–1278. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.8.1276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hocaoglu C, Babuc ZT. Suicidal ideation in patients with schizophrenia. Isr J Psychiatry Relat Sci V. 2009;46(3):195–203. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutton P, Bowe S, Parker S, Ford S. Prevalence of suicide risk factors in people at ultra-high risk of developing psychosis: a service audit. Early Interv Psychiatry. 2011;5:375–380. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7893.2011.00302.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jovanovic N, Podlesek A, Medved V, Grubisin J, Mihaljevic-Peles A, Goran T, Lovretic V. Association between psychopathology and suicidal behavior in schizophrenia: A cross-sectional study of 509 participants. Crisis. 2013;34(6):374–381. doi: 10.1027/0227-5910/a000211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kontaxakis V, Hayaki-Kontaxaki B, Margariti M, Stamouli S, Kollias C, Christodoulou G. Suicidal ideation in inpatients with acute schizophrenia. Can J Psychiat. 2004;49(7):476–479. doi: 10.1177/070674370404900709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller TJ, McGlashan TH, Rosen JL, Cadenhead K, Ventura J, McFarlane W, Perkins DO, Pearlson GD, Woods SW. Prodromal Assessment with the Structured Interview for Prodromal Syndromes and the Scale of Prodromal Symptoms: Predictive Validity, Interrater Reliability, and Training to Reliability. Schizophrenia Bull. 2003;4(29):703–715. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a007040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niendam TA, Bearden CE, Johnson JK, Cannon TD. Global Functioning Scale: Role (GFS: Role) Los Angeles: University of California; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Palmier-Claus J, Shryane N, Taylor P, Lewis S, Drake R. Mood variability predicts the course of suicidal ideation in individuals with first and second episode psychosis. Psychiat Res. 2013;206(2):240–245. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2012.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pompili M. Exploring the phenomenology of suicide. Suicide Life-Threat Behav. 2010;40(3):234–244. doi: 10.1521/suli.2010.40.3.234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pompili M, Serafini G, Innamorati M, Lester D, Shrivastava A, Girardi P, Nordentoft M. Suicide risk in first episode psychosis: A selective review of the current literature. Schizophr Res. 2011;129:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2011.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Posner K, Brown GK, Stanley B, Brent DA, Yershova KV, Oquendo MA, Currier GW, Melvin GA, Greenhill L, Shen S, Mann JJ. The Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale: initial validity and internal consistency findings from three multisite studies with adolescents and adults. Am J Psychiat. 2011;168(12):1266–1277. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2011.10111704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preti A, Meneghelli A, Pisano A, Cocchi A, The Programma 2000 Team Risk of suicide and suicidal ideation in psychosis: Results from an Italian multi-modal pilot program on early intervention in psychosis. Schizophr Res. 2009;113:145–150. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2009.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez-Gistau V, Baeza I, Arango C, Gonzalez-Pinto A, de la Serna E, Parellada M, Graell M, Paya B, Llorente C, Castro-Fornieles J. Predictors of suicide attempt in early-onset, first-episode psychoses: a longitudinal 24-month follow-up study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2013;74(1):59–66. doi: 10.4088/JCP.12m07632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skodlar B, Tomori M, Parnas J. Subjective experience and suicidal ideation in schizophrenia. Compr Psychiat. 2008;4:482–488. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2008.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor PJ, Gooding PA, Wood AM, Johnson J, Pratt D, Tarrier N. Defeat and entrapment in schizophrenia: The relationship with suicidal ideation and positive psychotic symptoms. Psychiat Res. 2010;178:244–248. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2009.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor PJ, Hutton P, Wood L. Are people at risk of psychosis also at risk of suicide and self-harm? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychol Med. 2015;45(5):911–926. doi: 10.1017/S0033291714002074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yung AR, Phillips LJ, Yuen HP, McGorry PD. Risk factors for psychosis in an ultra high-risk group: psychopathology and clinical features. Schizophr Res. 2004;67:131–142. doi: 10.1016/S0920-9964(03)00192-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]