Abstract

Heparan and chondroitin/dermatan sulfated proteoglycans have a wide range of roles in cellular and tissue homeostasis including growth factor function, morphogen gradient formation, and co-receptor activity. Proteoglycan assembly initiates with a xylose monosaccharide covalently attached by either xylosyltransferase I or II. Three individuals from two families were found that exhibited similar phenotypes. The index case subjects were two brothers, individuals 1 and 2, who presented with osteoporosis, cataracts, sensorineural hearing loss, and mild learning defects. Whole exome sequence analyses showed that both individuals had a homozygous c.692dup mutation (GenBank: NM_022167.3) in the xylosyltransferase II locus (XYLT2) (MIM: 608125), causing reduced XYLT2 mRNA and low circulating xylosyltransferase (XylT) activity. In an unrelated boy (individual 3) from the second family, we noted low serum XylT activity. Sanger sequencing of XYLT2 in this individual revealed a c.520del mutation in exon 2 that resulted in a frameshift and premature stop codon (p.Ala174Profs∗35). Fibroblasts from individuals 1 and 2 showed a range of defects including reduced XylT activity, GAG incorporation of 35SO4, and heparan sulfate proteoglycan assembly. These studies demonstrate that human XylT2 deficiency results in vertebral compression fractures, sensorineural hearing loss, eye defects, and heart defects, a phenotype that is similar to the autosomal-recessive disorder spondylo-ocular syndrome of unknown cause. This phenotype is different from what has been reported in individuals with other linker enzyme deficiencies. These studies illustrate that the cells of the lens, retina, heart muscle, inner ear, and bone are dependent on XylT2 for proteoglycan assembly in humans.

Main Text

Proteoglycans (PGs) are a class of surface-associated and extracellular matrix proteins that play a key role in many tissues.1–3 They are intimately involved in cellular homeostasis, impacting many fundamental biological processes including growth factor function, morphogen gradient formation, and co-receptor activity. The various PGs, except hyaluronic acid and keratan sulfate, share a common structure, consisting of a core protein on which glycosaminoglycan (GAG) disaccharide side chains are assembled. Two main groups of sulfated PGs, distinguished based on differences in GAG disaccharides, are heparan sulfate proteoglycan (HSPG) and chondroitin sulfate/dermatan proteoglycan (CS/DSPG).1

HSPGs and CS/DSPGs are very heterogeneous in regards to the types and number of GAG chains and the core protein modified; however, they share a common linker tetrasaccharide chain on which the GAG side chains are assembled on the core proteins. The first of these linker sugar residues is xylose, which is attached to a designated serine residue of the core protein by xylosyltransferases (XylTs). Two enzymes with XylT activity have been identified in humans, XYLT1 (MIM: 608124) and XYLT24 (MIM: 608125), and XylT activity is required for HSPG and CS/DSPG assembly.5 Three additional sugar residues of the linker region are then added as galactose-galactose-glucuronic acid. Defects at each step of these sugar additions causes various autosomal-recessive disorders (MIM: 604327, 606374),6,7 illustrating the importance of PG in tissue homeostasis.

XYLT1 and XYLT2 are very similar in function and are co-expressed in many tissues, but some temporal, spatial, and tissue-specific differences in expression exist5,8 and at the cellular level one or the other can be exclusively expressed.9,10 Predictably, reduced activity could differentially affect some tissues or developmental periods respective to the isoform affected. For example, in animal models and humans, impaired XYLT1 function is associated with cartilage abnormalities due to defects in endochondral ossification and growth.7,8,11 These observations suggest that XYLT1 is critically important for growth cartilage and that its deficiency is not compensated for by XYLT2 in this tissue.

The genetic syndromes characterized by osteoporosis, eye involvement with or without hearing impairment, and intellectual disability include osteoporosis pseudoglioma (OPPG [MIM: 259770]) syndrome and spondylo-ocular syndrome (SOS [MIM: 605822]). The majority of individuals with OPPG have mutations in low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 5 (MIM: 603506). The first report of SOS described five affected members of a consanguineous family who had retinal detachment, cataract, facial dysmorphism, generalized osteoporosis, immobile spine, and platyspondyly.12 Only one other family with SOS has been reported.13 The causative mutation for SOS is unknown.

This report describes three individuals from two unrelated families with a SOS-like phenotype including bone fragility, hearing impairment, heart septal defects, and learning difficulties. Whole exome sequencing and Sanger sequence analyses revealed that all individuals possess homozygous frameshift mutations in XYLT2 that resulted in premature termination of transcription. Each of the mutated XYLT2 loci results in decreased circulating XylT activity and fibroblasts from the individuals demonstrate reduced HS and CS assembly in PGs. These findings illustrate the unique role of XylT2-dependent PGs to tissue homeostasis. All affected family members or their legal guardians provided written informed consent and all studies were approved by the Sydney Children’s Hospital Network Ethics Committee or Institutional Review Board of McGill University.

The two index cases for this study are brothers from non-consanguineous healthy parents of European Australian descent (Figure 1A, II-1 and II-2) evaluated at the Children’s Hospital at Westmead in Westmead, Australia. Although non-consanguineous, there is a high likelihood of endogamy because of the geographical isolation of the parents’ region of origin. Individual 1 (II-1 in Figure 1) was born at 39 weeks gestation by spontaneous vaginal delivery. Birth weight was 3,990 g (>90th centile), length 52 cm (90th centile), and occipito-frontal circumference 33.5 cm (10th centile). Examination at birth noted webbed neck and lymphedema of lower extremities. Investigations showed normal results for karyotype, comparative genomic hybridization micro-array, urine metabolic screen, TORCH screen, and brain MRI.

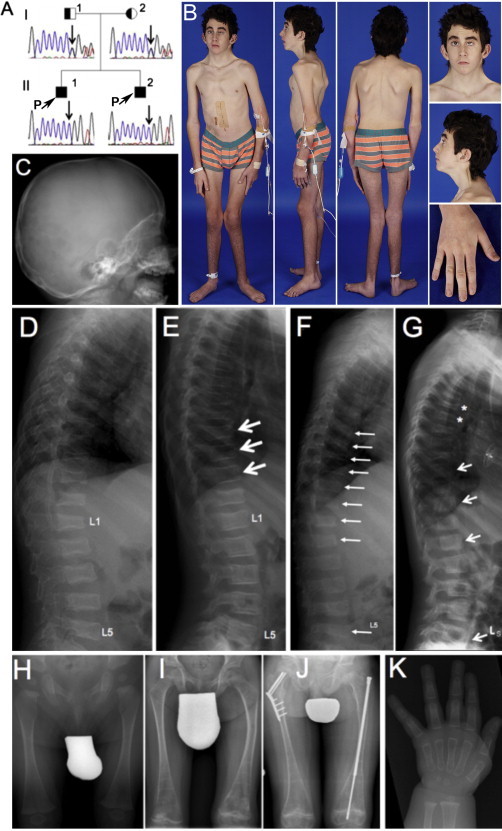

Figure 1.

Clinical and Radiological Findings in Individuals 1 and 2

(A) Pedigree and results of Sanger sequencing in individual 1 (II-1) and individual 2 (II-2).

(B) Clinical aspect of individual 1 at 14 years of age.

(C) Calvarial bone is thin (18 months). The dens axis appears normal.

(D) Lateral spine radiograph of individual 1 at the age of 18 months. All thoracic and lumbar vertebrae are deformed or fractured.

(E) At 7 years of age (after 3 years of pamidronate treatment), some vertebral bodies have undergone marked reshaping, indicated by arrows.

(F) Lateral spine radiograph of individual 2 at the age of 12 months. Several vertebrae are deformed or fractured, indicated by arrows.

(G) After 6 years of pamidronate treatment (age 7 years), some vertebral bodies have reshaped (arrows), but new compression fractures have developed in other vertebra (asterisks).

(H–J) Femur radiographs of individual 2 at 6 months (H), 8 years (I), and 11 years (J) of age. Despite pamidronate treatment, femoral deformities and at least three fractures developed, necessitating hardware insertion.

(K) Hand radiograph in individual 2 at 6 months of age, showing thin cortices.

At 18 months of age, individual 1 suffered a right femoral fracture and was found to have multiple vertebral compression fractures and generalized vertebral flattening (Figure 1D). Physical examination revealed a low posterior hairline, short webbed neck, posteriorly rotated and low-set ears, shield chest, undescended left testis (requiring orchidopexy), long fingers and toes, and overriding second and third toes. Sclerae and teeth were normal. Dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry showed a low total body areal bone mineral density (BMD) Z score of −1.8 and a low lumbar spine areal BMD, Z score of −2.5. Treatment with intravenous pamidronate infusions was started at 20 months and resulted in reshaping of several vertebrae (Figure 1E). However, new vertebral compression fractures occurred despite therapy. At 14 years of age, he was fully ambulant but had an unsteady gait due to muscle weakness and poor vision (see below), and he had sustained five additional long-bone fractures.

In addition to musculoskeletal defects, this individual showed defects in cardiovascular and urinary systems. Echocardiography had detected an atrial septal defect that was surgically corrected at 8 years. It also revealed a mitral valve prolapse and dysplastic aortic valve. At 14 years of age, growth continued on the 25th–50th centile for height and 20th–50th for weight. He had a noticeable pectus carinatum with inferior depression and persistence of disproportionately long and slender fingers and toes, a low posterior hairline, short webbed neck, and posteriorly rotated and low-set ears (Figure 1B). Ultrasound showed mild to moderately dilated bilateral distal ureters of uncertain etiology but a normal appearance of kidneys, liver, and biliary systems. However, he developed a perforated duodenal ulcer, which required surgical intervention.

Mild to moderate sensorineural hearing loss was diagnosed at 9 years of age and he was fitted with hearing aids. Ophthalmological examination showed amblyopia and nystagmus, and at 11 years of age he developed a spontaneous left retinal detachment that resulted in loss of vision in the affected eye. At 13 years, posterior sub-capsular cataracts were noted. Learning difficulties were confirmed at 6 years of age but were difficult to assess formally because of visual and hearing disabilities. Subsequent assessments confirmed that he was functioning in the mild learning difficulty group.

Individual 2 (II-2 in Figure 1) had a clinical course very similar to that of individual 1, his brother. He had generalized vertebral flattening, and compression fractures were detected at 3 and 12 months of age (Figure 1F). Thin cortices were discovered in metacarpal and phalanges and calvarial bones at 6 and 18 months of age (Figures 1C and 1K). Treatment with intravenous pamidronate was started at the age of 12 months. By 7 years of age, reshaping of some vertebral bodies was noted but new compression fractures were apparent (Figure 1G). Bilateral deformities (Figures 1H and 1I) and femoral fractures were apparent at the last follow up at 11 years of age (Figure 1J). At this age, he was ambulating independently. Growth continued along the 25th–50th centile for height and 25th–75th centile for weight. Cardiac findings, sensorineural hearing loss, and urinary tract findings were identical to that of his brother. He underwent cardiac surgery and was fitted with hearing aids. Mild learning difficulties were noted at 6 years of age.

The parents of individuals 1 and 2 were both clinically normal. Neither the father nor mother had any unexplained fractures or musculoskeletal abnormalities at 40 and 39 years of age, respectively. Clinical examination of both parents, including anthropometry, was normal. Bone mineral densitometry by dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry and peripheral quantitative computed tomography were normal for the mother and elevated for the father (total body areal BMD Z score 3.9).

To identify the gene variant and cause of this phenotype in this family, we performed whole exome sequencing on the genomic DNA of the affected individuals (see details in Supplemental Data). After removing common variants, 327 and 301 variants were identified in individuals 1 and 2, respectively. The analysis of sequencing data did not reveal any rare variants within the ten genes (PTPN11 [MIM: 176876], BRAF [MIM: 164757], HRAS [MIM: 190020], KRAS [MIM: 190070], MAPK1 [MIM: 176948], MAPK2, SHOC2 [MIM: 602775], RAF1 [MIM:164760], SOS1 [MIM: 182530], and RIT1 [MIM: 691591]) already associated with Noonan syndrome or the known osteogenesis imperfecta genes (CRTAP [MIM: 605497], LEPRE1 [MIM: 610915], PPIB [MIM: 123841], SERPINH1 [MIM: 600943], FKBP10 [MIM: 607063], SP7 [MIM: 606633], SERPINF1 [MIM: 172860], BMP1 [MIM: 112264], TMEM38B [MIM: 611236], IFITM5 [MIM: 614757], and WNT1 [MIM: 164820]). The presence of the disease in two brothers with apparently healthy parents suggested an autosomal-recessive or X-linked recessive inheritance. Therefore, we prioritized candidate gene variants with homozygous mutations shared by the two affected siblings, and this led to the identification of one frameshift duplication in XYLT2 and one missense variant in each of four different genes (FTSJ3, SLC38A10, CCDC57, and SH3KBP1 [MIM: 300374]) (Table S3).

Considering the function of these four latter variants, we concluded that they were unlikely to be responsible for the disease: the complete deletion of SH3KBP1 (encoding CIN85) has been previously reported in a male individual with autism who did not show any dysmorphic features.14 Furthermore, mice deficient of CIN85 expression were viable, fertile, and displayed no obvious structural abnormalities.15 The SLC38A10 variant (MAF: 0.001 in EVS) was not evolutionally conserved and predicted inconsequential to protein function by three different bioinformatics algorithms.16 A recent phenotypic screening of Ccdc57 knockout mice revealed two significant abnormalities (hydrocephaly and abnormal hypodermis fat layer), which were not observed in our individuals. Finally, FTSJ3 function is not fully characterized, but it might play a role in 18S rRNA synthesis17 and no disease-related allele and phenotype has been yet reported for this gene.

In contrast, several lines of evidence suggested that the XYLT2 variant was potentially responsible for the observed phenotypes. The homozygous frameshift duplication in XYLT2 is the most deleterious of the identified variants and most likely results in nonsense-mediated degradation of the mutant transcript and a consequent loss of XylT2. Notably, the closely related enzyme XYLT1 has previously been shown to be required for HSPG and CS/DSPG assembly, and a missense homozygous mutation in XYLT1 resulted in an autosomal-recessive short stature syndrome associated with intellectual disability.7

Both individuals 1 and 2 harbor a homozygous frameshift duplication of C in exon 3 of XYLT2 (GenBank: NM_022167.3; c.692dup) that results in the loss of the last 634 amino acids of XYLT2 and insertion of 53 novel amino acids (p.Val232Glyfs∗54) before a premature stop codon. The variant was located within about 23 Mb shared region of homozygosity (Figure S1) and was not seen in our exome database (∼1,000 individuals) or in the 1000 Genomes, dbSNP132, the EVS, or the ExAC (∼63,000 exomes of unrelated individuals) databases. The inserted sequence was confirmed by Sanger sequencing of genomic DNA from both boys (Figures 1A and S1). This mutation was further confirmed by sequence analyses of fibroblast XYLT2 mRNA (see below, Figure S2). Analyses showed that the parents were heterozygous for this mutation. All loci from the index individuals and parents were confirmed to be in XYLT2 by Sanger sequencing of XYLT2 exon 3.

Affected individual serum and plasma XylT activity levels were determined to investigate the biochemical impact of the XYLT2 mutation. Because platelets are a substantial source of XylT2 activity in serum, comparison of XylT activity in serum to plasma reflects an important cell-specific source of XylT2.18 As compared to adult control serum and plasma, individuals 1 and 2 had an approximately 75% and 57% drop in serum and plasma XylT activity, respectively (Figure 2A). Because age and pamidronate treatment can alter XylT levels, serum from age-matched pamidronate-treated individuals with osteogenesis imperfecta were used as controls (Figure 2B). These findings show that the study individuals have substantial reductions in circulating XylT activity.

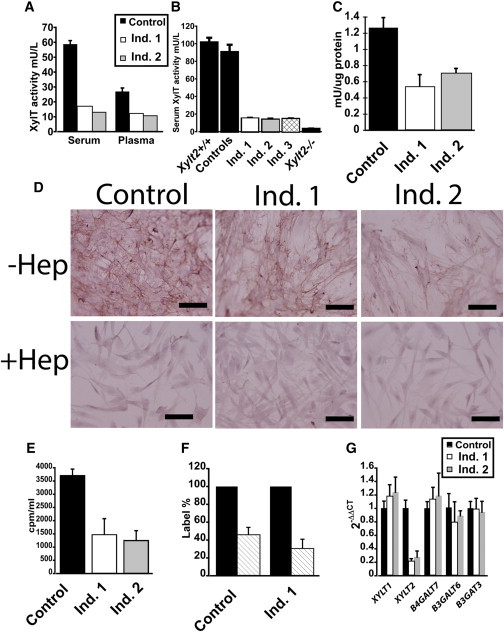

Figure 2.

Reduced XylT Activity in Affected Individuals

(A) Individual 1 (Ind. 1) and individual 2 (Ind. 2) serum and plasma XylT activity as compared to adult male control subjects (n = 4).

(B) Serum XylT activity in individuals 1, 2, and 3 as compared to age-matched control subjects (n = 4). XylT levels in wild-type (Xylt2+/+) and in our XylT2-deficient (Xylt2−/−) mice19 are also illustrated (n = 3 each) for comparison; error bars represent SD. Total XylT activity was assayed via published protocols18 and for the study individuals’ values, these represent the mean of triplicate measurements. For age- and sex-matched control subjects, these were individuals with osteogenesis imperfecta and being treated with pamidronate. Affected individuals and control plasma were isolated from potassium EDTA-treated blood. In brief, serum (10 μl) and cell lysates (50 μl) were incubated in a total reaction volume of 100 μl containing 25 mM 2-(4-morpholino)-ethane sulfonic acid (pH 6.5), 25 μl KCl, 5 mM of KF, MnCl2 and MgCl2 with 1.13 μm UDP-[14C]-D-Xylose 150–250 mCi/mol (Perkin Elmer), 7.46 μm UDP-D-Xylose (Carbosource, University of Georgia, Atlanta, GA), and 160 μm of bikunin acceptor peptide (Biosynthesis) for 1 hr at 37°C. The reaction was stopped by chilling samples on ice. Labeled peptide was precipitated with 1.5 mg of BSA carrier, 500 μl of 10% trichloroacetic acid, and 4% phosphotungstic acid. Pellets were collected by centrifugation, washed with 750 μl of 5% trichloroacetic acid, and dissolved in 400 μl of 1 N NaOH. Radioactivity in the resuspension was measured and one unit of enzyme activity represents incorporation of 1 μmol xylose/min into the acceptor peptide. For serum, the enzyme activity was calculated as mU/l and for cell lysates, the enzyme activity was calculated as mU/mg of protein in the lysate.

(C) XylT activity in dermal fibroblast lysate. Dermal fibroblasts from the affected individuals and parents were grown in Fibroblast Growth Kit-Low Serum (ATCC-PCS-221-041) supplemented with 1% penicillin/streptomycin at 37°C and 5% CO2. Primary dermal adult fibroblasts (ATCC, PCS-201-012) were used as the control and grown in same culture conditions. Confluent cells were trypsinized and passaged 1:10. No cells were grown more than passage 10. Values are means of triplicate measurements and error bars are the SD.

(D) Immunohistochemistry for HS shows that affected individuals’ fibroblasts have reduced levels of HS illustrated by reduced red staining that is subsequently removed with heparitinase III digestion. Scale bars represent 100 μm. –Hep is undigested cells, +Hep is heparitinase III-digested cells.

(E) Sulfate incorporation assays by study individuals’ fibroblasts shows a reduction in 35S incorporation where individual 1 is 60% and individual 2 is 66% reduced as compared to control fibroblasts.

(F) Digestion of eluted 35S labeled GAGs from control fibroblasts of 54% and individual 1 of 67% with chondroitinase ABC and heparitinase III in hashed bars. Undigested labeled GAGs are set at 100% in black bars.

(G) Real-time quantitative reverse transcription PCR of fibroblast mRNA for proteoglycan linker enzymes done in triplicate. RNA was isolated from near to confluent cells from vented T75 flasks with TRIzol reagent (Cat # 15596-018, Life Technologies), treated with DNase I (Cat # M0303S, NEB), and then cleaned up with TRIzol reagent. 5 μg of RNA was used to generate cDNA with Superscript III cDNA synthesis kit (Cat #18080-051, Invitrogen) or MMLV reverse transcriptase via random hexamers primers. Quantitative real-time PCR was performed on cellular cDNA using gene-specific primers as listed in Table S2. GAPDH expression was used for normalization on each plate. Each sample was analyzed in triplicate and three independent experiments were conducted for each target and the mean and standard deviation were calculated by 2− ΔΔ Ct. Individual 1 fibroblasts had a 77% decrease and individual 2 fibroblasts had a 72% decrease in XYLT2 mRNA. Values are means of triplicate measurements, normalized to GAPDH, and error bars are the standard deviation. Control mRNA is from normal dermal fibroblasts (ATCC).

Dermal fibroblasts were isolated to further evaluate the genetic and resultant enzyme defect in individuals 1 and 2. Total XylT activity in cell lysates from these cultures cells showed the fibroblasts had an approximate 60% decrease for individual 1 and 45% decrease for individual 2 as compared to normal dermal fibroblasts (Figure 2C). Based on our previous findings that fibroblasts express both XYLT1 and XYLT2,9 we suspected that the residual XylT activity is due to XYLT1 expression. PG assembly was investigated by immunohistochemistry and 35SO4 incorporation assays. We examined HSPG assembly levels by using GAG-specific antibody 10E4 performed as previously described.19 These results showed a qualitative decrease in HS GAG staining in the affected individuals’ fibroblasts (Figure 2D). 35SO4 incorporation by affected individuals’ fibroblasts performed as described20 with 25 μCi/ml for 24 hr showed a quantitative decrease of 60%–65% in total 35SO4 incorporation by the cells (Figure 2E). Chondroitinase ABC and heparitinase III digestion of the labeled PGs from these cells shows that both HS and CS are affected by the loss of XylT2 (Figure 2F) where in individual 1 there is 67% in loss of 35SO4 with digestion. In all, these results confirm a significant defect in PG assembly due to the XYLT2 mutation.

We suspected that the low XYLT2 mRNA levels were due to premature translation termination leading to mRNA decay. To investigate, we cloned and sequenced XYLT2 cDNA in triplicate from individual 2’s fibroblasts. The sequence confirmed the cytosine duplication (c.692dup) in exon 3, the frame shift mutation, the addition of 53 non-conserved amino acids, and the fact that the premature termination would severely truncate and disrupt a highly conserved portion of the protein, resulting in a mature mutant protein lacking any of the predicted catalytic domain (see Figure S2). In support of premature termination and mRNA decay, expression analyses by quantitative real-time RT-PCR showed that the affected individuals had a 75% decrease in XYLT2 mRNA. Significantly, there was no change in any of the other proteoglycan linker enzyme mRNA levels (Figure 2G; see Table S2) including XYLT1, confirming our earlier suspicion that the affected individuals’ fibroblasts have residual XylT activity due to XYLT1. In all, these results demonstrate that the clinical observations in the affected individuals are due to a selective loss of XylT2 arising from a premature translational termination and likely mRNA decay.

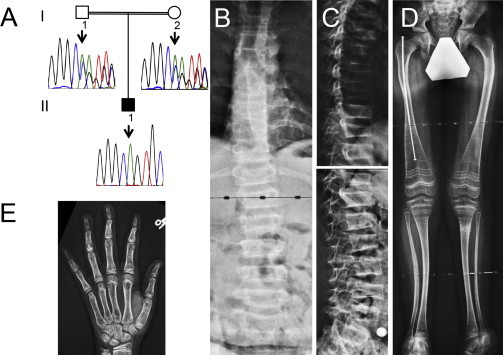

After a mutation of XYLT2 had been identified in individuals 1 and 2, an unrelated boy (individual 3, II-1 in Figure 3) undergoing treatment with pamidronate and with phenotypic similarities to individuals 1 and 2 came to our attention. Individual 3 was born prematurely after 35 weeks of pregnancy. The parents are first cousins. Both parents and the two older siblings are healthy. Individual 3 sustained his first fracture, affecting the right femur, at the age of 18 months, and two more right femur fractures in the subsequent 2 years. When first examined at our institution at 3.9 years of age, he was very short (90 cm, corresponding to 5 cm below the 5th percentile) and his weight was low (12.2 kg, corresponding to 1.5 kg below the 5th percentile). Limbs were straight with normal range of motion in the hip, but there was mild left hemiplegia with spasticity in the left lower extremity. Radiographs revealed multiple vertebral compression fractures (Figure 3). There was no dentinogenesis imperfecta and sclerae were white. Areal bone mineral density Z score at the lumbar spine was −5.8. Treatment with intravenous pamidronate was started, which was associated with an increase in lumbar spine areal bone mineral density Z score to −3.6 within 12 months. Bisphosphonate treatment was continued with varying protocols until 18 years of age, when lumbar spine areal bone mineral density Z score was −1.4. Despite this treatment, he sustained a total of ten lower extremity fractures and he was never able to walk independently. At the time of the last follow-up (at 19 years of age), he was using a wheelchair for all mobility; height was 145 cm and weight 48 kg.

Figure 3.

Clinical and Radiological Findings in Individual 3

(A) Results of Sanger sequencing. Individual 3 (II-1 in the pedigree) is homozygous for a c.520del mutation in XYLT2, and the parents are heterozygous for this deletion.

(B) Antero-posterior radiograph of the spine. Most vertebrae appear decreased in height.

(C) Lateral spine radiograph showing severe vertebral compression fractures.

(D) Mild deformities of the lower extremities. The right femur has been rodded after fracture. The metaphyseal lines that are prominent in distal femurs and proximal tibias are due to treatment with intravenous pamidronate infusions.

(E) Radiograph of the left hand and wrist, showing somewhat thin cortices.

Apart from musculoskeletal issues, a hearing deficit was noted at 10 years of age in individual 3 and hearing aids were fitted. Bilateral cataract was diagnosed at 12 years of age and treated with removal of the lenses. At 15 years of age, retinal detachment occurred in the right eye. No heart or lung abnormalities had been noted. He attended regular school, with normal academic performance.

Given the noted phenotypic similarities to individuals 1 and 2, we measured serum XylT activity in individual 3. XylT activity was similar to that of 1 and 2 (Figure 2B), so we performed Sanger sequencing of XYLT2 in individual 3. This revealed that individual 3 was homozygous for a c.520del mutation in exon 2 that resulted in a frameshift and premature stop codon p.Ala174Profs∗35 (Figure 3A).

The skeletal phenotype of these boys resembles those of a sibship described as SOS (Table S1).12 The only other recognized disorder to be associated with vertebral compression fractures and eye disease is osteoporosis-pseudoglioma syndrome (OPPG) (MIM: 259770) due to mutations in LRP5 (MIM: 603506). However, OPPG involves ocular defects due to hyperplasia of the vitreous, corneal opacity, secondary glaucoma,21 and growth plate abnormalities causing dwarfism in some individuals.22,23 Our subjects also showed variable stature, with the first two individuals having normal stature and the third showing significant short stature, suggesting variable impact on growth cartilage. However, the chest wall deformity seen in case subjects 1 and 2 might reflect dysplastic growth of costal cartilages. It should be noted that short bones are found in both zebrafish and mice harboring hypomorphic Xylt1 alleles,8,11 and in such mice, no Xylt2 expression was detected in articular cartilage tissue, suggesting that articular cartilage GAG assembly is highly XylT1 dependent. These findings suggest that XylT1 and XylT2 can impact cartilage but that the effect might be variable depending on the location of the cartilage and the type of cartilage. This indicates that we would not expect XylT2 deficiency to affect articular cartilage, but growth plate cartilage might require both XylT1 and XylT2 activity. Therefore, defects in XYLT1 or those in the remaining enzymatic steps of linker assembly would be expected to affect growth cartilage, and this is supported by observations made in individuals with hypomorphic mutations in XYLT1 and mutations in B4GALT7 (beta1,4-galacosyltransferase 7), B3GALT6 (beta1,3-galactosyltransferase 6) (MIM: 604327), and B3GAT3 (beta1,3-glucuronyltransferase 3) (glucuronyltransferase I) (MIM: 606374) who have significant short stature6,24,25 (MIM: 606374, 604327). Given the variable growth seen in our three subjects, further assessment of XYLT1 and XYLT2 expression in the growth plate is required.

In summary, we have discovered two frameshift mutations of XYLT2 that lead to truncation of XylT2 and elimination of the catalytic domain resulting in severe XylT deficiency as demonstrated in reduced serum and plasma XylT activity and giving rise to defects in musculoskeletal, myocardial, ocular, inner ear, and central nervous system tissues where XYLT1 expression fails to compensate. This indicates that XylT2 is critical for PG assembly in these tissues.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful for the involvement of the study individuals and their families. We acknowledge the contribution of the general pediatrician, Dr. David McDonald of Port Macquarie, NSW, who referred and coordinated the care of the extraskeletal features including their learning disabilities and hearing impairment and supervised their interval Pamidronate therapy. We are indebted to Patty Mason for technical assistance, to Mark Lepik for preparing the figures, and to Michaela Durigova for providing clinical information. The authors wish to acknowledge the McGill University and Génome Québec Innovation Centre, Montreal, Canada for performing the exome sequencing and Sanger sequencing analyses. We also thank Phillip A. Wood for critical reading of the manuscript. This work was supported by the Shriners of North America. F.R. received support from the Chercheur-Boursier Clinicien program of the Fonds de recherche du Québec - Santé. J.P.M. is supported by the NIH grants AI062629 and GM103648 and by the Merit Review Program of the Department of Veterans Affairs. M.E.H., N.P., and M.C.M. are supported by a Research Advisory Committee grant, Oklahoma State University College of Veterinary Medicine, and NIH DK087989. The findings herein are the views and conclusions of the authors and not the NIH.

Supplemental Data

Web Resources

The URLs for data presented herein are as follows:

1000 Genomes, http://browser.1000genomes.org

Database of Genomic Variants (DGV) Genomic Variants in Human Genome, http://dgvbeta.tcag.ca/gb2/gbrowse/dgv2_hg19/

ExAC Browser (accessed October 2014), http://exac.broadinstitute.org/

Human Gene Mutation Database, http://www.hgmd.org/

NHLBI Exome Sequencing Project (ESP) Exome Variant Server (June 20, 2012), http://evs.gs.washington.edu/EVS/

OMIM, http://www.omim.org/

UCSC Genome Browser, http://genome.ucsc.edu

References

- 1.Couchman J.R., Pataki C.A. An introduction to proteoglycans and their localization. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 2012;60:885–897. doi: 10.1369/0022155412464638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Esko J.D., Kimata K., Lindahl U. Proteoglycans and sulfated glycosaminoglycans. In: Varki J.D.E.A., Colley K.J., editors. Essentials of Glycobiology. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; Cold Spring Harbor: 2009. pp. 229–248. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sarrazin S., Lamanna W.C., Esko J.D. Heparan sulfate proteoglycans. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2011;3:3. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a004952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Götting C., Kuhn J., Zahn R., Brinkmann T., Kleesiek K. Molecular cloning and expression of human UDP-d-Xylose:proteoglycan core protein beta-d-xylosyltransferase and its first isoform XT-II. J. Mol. Biol. 2000;304:517–528. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.4261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hinsdale M.E. Xylosyltransferase I, II. In: Taniguchi N., Fukuda M., Narimatsu H., Yamaguchi Y., Angata T., editors. Handbook of Glycosyltransferases and Related Genes. Springer-Verlag; Berlin: 2014. pp. 873–883. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Malfait F., Kariminejad A., Van Damme T., Gauche C., Syx D., Merhi-Soussi F., Gulberti S., Symoens S., Vanhauwaert S., Willaert A. Defective initiation of glycosaminoglycan synthesis due to B3GALT6 mutations causes a pleiotropic Ehlers-Danlos-syndrome-like connective tissue disorder. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2013;92:935–945. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2013.04.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schreml J., Durmaz B., Cogulu O., Keupp K., Beleggia F., Pohl E., Milz E., Coker M., Ucar S.K., Nürnberg G. The missing “link”: an autosomal recessive short stature syndrome caused by a hypofunctional XYLT1 mutation. Hum. Genet. 2014;133:29–39. doi: 10.1007/s00439-013-1351-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eames B.F., Yan Y.L., Swartz M.E., Levic D.S., Knapik E.W., Postlethwait J.H., Kimmel C.B. Mutations in fam20b and xylt1 reveal that cartilage matrix controls timing of endochondral ossification by inhibiting chondrocyte maturation. PLoS Genet. 2011;7:e1002246. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cuellar K., Chuong H., Hubbell S.M., Hinsdale M.E. Biosynthesis of chondroitin and heparan sulfate in chinese hamster ovary cells depends on xylosyltransferase II. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:5195–5200. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M611048200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Roch C., Kuhn J., Kleesiek K., Götting C. Differences in gene expression of human xylosyltransferases and determination of acceptor specificities for various proteoglycans. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2010;391:685–691. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.11.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mis E.K., Liem K.F., Jr., Kong Y., Schwartz N.B., Domowicz M., Weatherbee S.D. Forward genetics defines Xylt1 as a key, conserved regulator of early chondrocyte maturation and skeletal length. Dev. Biol. 2014;385:67–82. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2013.10.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schmidt H., Rudolph G., Hergersberg M., Schneider K., Moradi S., Meitinger T. Retinal detachment and cataract, facial dysmorphism, generalized osteoporosis, immobile spine and platyspondyly in a consanguinous kindred—a possible new syndrome. Clin. Genet. 2001;59:99–105. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-0004.2001.590206.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Alanay Y., Superti-Furga A., Karel F., Tunçbilek E. Spondylo-ocular syndrome: a new entity involving the eye and spine. Am. J. Med. Genet. A. 2006;140:652–656. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.31119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pinto D., Delaby E., Merico D., Barbosa M., Merikangas A., Klei L., Thiruvahindrapuram B., Xu X., Ziman R., Wang Z. Convergence of genes and cellular pathways dysregulated in autism spectrum disorders. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2014;94:677–694. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2014.03.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shimokawa N., Haglund K., Hölter S.M., Grabbe C., Kirkin V., Koibuchi N., Schultz C., Rozman J., Hoeller D., Qiu C.H. CIN85 regulates dopamine receptor endocytosis and governs behaviour in mice. EMBO J. 2010;29:2421–2432. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2010.120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kumar P., Henikoff S., Ng P.C. Predicting the effects of coding non-synonymous variants on protein function using the SIFT algorithm. Nat. Protoc. 2009;4:1073–1081. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2009.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Morello L.G., Coltri P.P., Quaresma A.J., Simabuco F.M., Silva T.C., Singh G., Nickerson J.A., Oliveira C.C., Moore M.J., Zanchin N.I. The human nucleolar protein FTSJ3 associates with NIP7 and functions in pre-rRNA processing. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e29174. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0029174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Condac E., Dale G.L., Bender-Neal D., Ferencz B., Towner R., Hinsdale M.E. Xylosyltransferase II is a significant contributor of circulating xylosyltransferase levels and platelets constitute an important source of xylosyltransferase in serum. Glycobiology. 2009;19:829–833. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwp058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Condac E., Silasi-Mansat R., Kosanke S., Schoeb T., Towner R., Lupu F., Cummings R.D., Hinsdale M.E. Polycystic disease caused by deficiency in xylosyltransferase 2, an initiating enzyme of glycosaminoglycan biosynthesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:9416–9421. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0700908104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang L., David G., Esko J.D. Repetitive Ser-Gly sequences enhance heparan sulfate assembly in proteoglycans. J. Biol. Chem. 1995;270:27127–27135. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.45.27127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Teebi A.S., Al-Awadi S.A., Marafie M.J., Bushnaq R.A., Satyanath S. Osteoporosis-pseudoglioma syndrome with congenital heart disease: a new association. J. Med. Genet. 1988;25:32–36. doi: 10.1136/jmg.25.1.32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Somer H., Palotie A., Somer M., Hoikka V., Peltonen L. Osteoporosis-pseudoglioma syndrome: clinical, morphological, and biochemical studies. J. Med. Genet. 1988;25:543–549. doi: 10.1136/jmg.25.8.543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.De Paepe A., Leroy J.G., Nuytinck L., Meire F., Capoen J. Osteoporosis-pseudoglioma syndrome. Am. J. Med. Genet. 1993;45:30–37. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320450110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nakajima M., Mizumoto S., Miyake N., Kogawa R., Iida A., Ito H., Kitoh H., Hirayama A., Mitsubuchi H., Miyazaki O. Mutations in B3GALT6, which encodes a glycosaminoglycan linker region enzyme, cause a spectrum of skeletal and connective tissue disorders. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2013;92:927–934. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2013.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Baasanjav S., Al-Gazali L., Hashiguchi T., Mizumoto S., Fischer B., Horn D., Seelow D., Ali B.R., Aziz S.A., Langer R. Faulty initiation of proteoglycan synthesis causes cardiac and joint defects. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2011;89:15–27. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2011.05.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.