Abstract

Background

Salvage surgical resection for non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) patients initially treated with definitive chemotherapy and radiation can be performed safely, but the long-term benefits are not well characterized.

Methods

Perioperative complications and long-term survival of all patients with NSCLC who received curative-intent definitive radiation with or without chemotherapy followed by lobectomy from 1995-2012 were evaluated.

Results

During the study period, 31 patients met inclusion criteria. Clinical stage distribution was: stage I (n=2,6%); stage II (n=5,16%); stage IIIA (n=15,48%);stage IIIB (n=5,16%); stage IV (n=3,10%); and unknown (n=1,3%). The reasons surgery was initially not considered were: patients deemed medically inoperable (5 [16%]); extent of disease considered unresectable (21 [68%]); small cell lung cancer misdiagnosis (1 [3%]); and unknown (4 [13%]). Definitive therapy was radiation alone (n=2, 6%), concurrent chemoradiation (n=28, 90%), and sequential chemoradiotherapy (n=1, 3%). The median radiation dose was 60 Gy. Patients were subsequently referred for resection because of obvious local relapse, medical tolerance of surgery or post-therapy imaging suggested residual disease.Median time from radiation to lobectomy was 17.7 weeks.There were no perioperative deaths, and morbidity occurred in 15 (48%) patients. None of 3 patients with residual pathologic nodal disease survived longer than 37 months, but the 5-year survival of pN0 patients was 36%. Patients who underwent lobectomy for obvious relapse (n=3) also did poorly with median overall survival of 9 months.

Conclusion

Lobectomy after definitive radiation therapy can be done safely and is associated with reasonable long-term survival, particularly when patients do not have residual nodal disease.

Keywords: “Lung cancer surgery”, “radiation therapy”

Introduction

Definitive radiation is indicated for patients with inoperable non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC)[1], but approximately 30% of patients with locally-advanced NSCLC experience local-regional recurrence after curative-intent chemotherapy and radiation [2]. Salvage primary tumor resection is sometimes considered for isolated local failures after definitive chemoradiation [3, 4], but is generally considered technically more difficult with potentially higher morbidity than when resection is performed after planned induction therapy. This increased complexity of salvage surgical resection is felt to result from both higher radiation doses as well as typically longer periods between radiation and surgery. Salvage lung resection is often not considered until more than 12 weeks after radiation [3], while surgery is usually performed 3 to 8 weeks after planned induction radiation [3, 5]. This increased time typically leads to operating in a field of radiation fibrosis with obliterated planes and tissue hypovascularity that makes dissection more difficult and also may impair wound healing [3].

Several studies have shown that lung resections can be safely performed after high-dose radiation therapy [3, 6-14]. However, these studies have generally been small and not considered salvage resections, and the potential long-term survival benefits of surgical resection in this situation have not been well-characterized. This study was undertaken to examine long-term outcomes of lobectomy for NSCLC after definitive radiation therapy and provide quantitative data regarding the benefits of surgery that can assist surgeons in the treatment decision process when they are evaluating patients in this clinical scenario.

Material and Methods

After obtaining Institutional Review Board approval with waiver of individual patient consent, a retrospective analysis of all NSCLC patients who received curative-intent definitive radiation with or without chemotherapy followed by lobectomy at Duke University Medical Center between January, 1995 and November, 2012 was performed. Administration of definitive chemoradiation versus definitive radiation alone was determined by the therapy protocols and physician preference and administered at several institutions, therefore not standardized. Patient inclusion criteria were: 1) biopsy-proven NSCLC prior to any therapy; 2) prior curative intent radiation with or without chemotherapy; 3) no a priori plan for eventual surgery; and 4) subsequent salvage lobectomy. A thoracic surgeon, medical oncologist, and radiation oncologist evaluated each patient prior to salvage surgery. Lung cancers were staged according to the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) 7th Edition of Lung Cancer Staging guidelines; patients treated at the time of earlier staging systems were recoded according to 7th edition definitions [15].

Baseline variables collected included demographics, comorbidities, tobacco use, pulmonary function, histology, pre-treatment clinical stage, and radiation and chemotherapy regimens. The use of both non-invasive (PET and CT) and invasive (cervical mediastinoscopy or endobronchial ultrasound) staging studies prior to both initial therapy and ultimate resection was also examined. Mediastinal lymph node dissection at the time of resection was routinely performed as previously described [16]. Perioperative variables collected included pathologic stage and operative and post-operative course, including details on chest tube duration, length of hospitalization, and complications. Outcome variables collected were overall and recurrence-free survival.

Overall survival and recurrence-free survival analyses were performed according to the Kaplan-Meier method and included all deaths from any cause in the follow-up period, with patients still alive censored at the last available follow-up. Overall survival was calculated from the time of lobectomy to death from any cause with patients censored at the time of last follow-up at Duke University Medical Center. Recurrence-free survival was calculated from the time of lobectomy to recurrence seen on imaging or death again with patients censored at the time of last follow-up. A multivariable Cox proportional hazard model for survival that included age, gender, pre-treatment clinical stage and residual disease as covariates was also fitted.

Patients were also grouped by primary indication for salvage lung resection in a similar fashion as previously described [3]: 1) Obvious local relapse—patients with PET scans after definitive radiation that initially showed no FDG uptake but subsequently demonstrated increased FDG uptake at the site of primary tumor diagnosed as relapse, with biopsy done in most patients. 2) Medical tolerance of surgery—patients previously deemed inoperable due to insufficient respiratory reserve or general frailty who were considered appropriate surgical candidates after re-evaluation with another provider or after having underwent sufficient rehabilitation and improvement. 3) Radiologic imaging that suggested residual disease—patients with either CT imaging suggesting residual disease or PET demonstrating hypermetabolic abnormality within the primary tumor or locoregional lymph nodes. In this scenario, surgeons often accepted the CT or FDG-PET results as a surrogate of risk for residual disease without preoperative tissue confirmation due to the known poor sensitivity and negative-predictive value of percutaneous biopsy specimens after definitive chemoradiation [3]. Survival of subgroups was compared using the log-rank test. All statistical analyses were performed using Stata Statistical Software: Release 12.0, StataCorp LP, College Station, TX.

Results

Pre-Resection Evaluation and Management

During the study period, 31 patients met inclusion criteria (Table 1). The median age at the time of surgery was 58 years (range, 40-78 years), and 13 (42%) of the patients were female. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) was the most common comorbidity and 23% of patients had previously had thoracic surgery. Clinical staging data prior to any treatment is also detailed in Table 1. All patients underwent a baseline CT of the chest and [18F] fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (FDG-PET) scan and full pulmonary function tests as part of their initial staging evaluation. Seventeen (55%) patients underwent CT and/or magnetic resonance image (MRI) of the brain. Only ten (32%) patients underwent invasive mediastinal staging prior to receiving definitive radiation. Seven of 15 patients who were clinically staged as having N2 disease had pathologic confirmation prior to starting treatment. No patients underwent resection for staging purposes.

Table 1.

Patient Characteristics and pre-resection treatment and staging characteristics

| Characteristics | No. of Patients | % All Patients |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Male | 18 | 58 |

| Female | 13 | 42 |

| Median age (range, years) | 58 | (40-78) |

| Ethnicity | ||

| White | 31 | 100 |

| FEV1 (%) (mean, SD) | 69 | 13 |

| DLCO (%) (mean, SD) | 70 | 20 |

| History of smoking | 29 | 94 |

| Median pack years, (range, years) | 40 | (0-105) |

| Cerebrovascular Disease | 0 | 0 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 2 | 6 |

| Renal insufficiency | 0 | 0 |

| Hypertension | 5 | 16 |

| CHF | 0 | 0 |

| CAD | 2 | 6 |

| COPD | 11 | 35 |

| PVD | 0 | 0 |

| Prior thoracic surgery | 7 | 23 |

| Other comorbidities | 5 | 16 |

| History of cancer | 5 | 16 |

| Pre-treatment Clinical Stage | ||

| IA | 1 | 3 |

| IB | 1 | 3 |

| IIA | 0 | 0 |

| IIB | 5 | 16 |

| IIIA | 15 | 48 |

| IIIB | 5 | 16 |

| IV | 3 | 10 |

| Unknown | 1 | 3 |

| Dose of Radiation | ||

| 40-49 | 2 | 6 |

| 50-59.3 | 1 | 3 |

| 59.4-64 | 16 | 52 |

| 65-70 | 9 | 29 |

| >70 | 2 | 6 |

| Unknown | 1 | 3 |

In 26 out of 31 patients, the initial staging and decisions for definitive radiation treatment were made at an outside institution and the patients were subsequently referred to a tertiary care center to consider salvage lung resection after completing definitive radiation therapy. A surgeon participated in 11 of 31 (35%) initial staging and treatment evaluations. All surgeons who performed the reevaluation after definitive radiation performed the operation. Reasons definitive radiation were pursued instead of surgery are detailed in Table 2. Of the five patients deemed medically inoperable, this decision was made without a formal evaluation by a surgeon in 4 patients.

Table 2.

Reasons for Definitive Radiation

| Rationale | N | Percent |

|---|---|---|

| Medically Inoperable | 5 | 16.1 |

| Inoperable due to extent of disease | ||

| Stage IIB, T3N0 (non-pancoast) | 3 | 9.7 |

| Pancoast tumor | 3 | 9.7 |

| Stage IIIA-N2 (single station) | 5 | 16.1 |

| Stage IIIB | 6 | 19.4 |

| Stage IV disease | 4 | 12.9 |

| Misdiagnosed with small cell | 1 | 3.2 |

| Deemed inoperable for unknown reasons | 4 | 12.9 |

All 31 patients received definitive curative-intent radiation, with a median dose to the primary tumor of 60 Gy, and 27 (87%) of patients received a dose greater than 59.3 Gy (Table 1). Twenty-nine (94%) patients received platinum-based chemotherapy concurrently with radiation therapy and 2 patients received definitive radiation treatment alone.

After definitive chemoradiation, radiologic imaging suggested all patients had disease without metastases or with previous metastases resected. The specific rationale for surgery is detailed in Table 3. For the 3 patients with obvious local relapse, the time between definitive radiation and surgery was 240, 300 and 700 days. These patients had no FDG uptake upon PET imaging performed after definitive radiation therapy but were found to have FDG uptake at the site of the primary mass in subsequent follow-up and were felt to have relapse.

Table 3.

Reasons for Surgery

| Rationale | N | Percent |

|---|---|---|

| Relapse seen by CT | 3 | 10 |

| Improved medical condition, residual disease by FDG-PET | 5 | 16 |

| Residual disease as suggested by radiologic imaging | 23 | 74 |

The decision for surgery was routinely discussed in a multidisciplinary setting with thoracic surgery and medical and radiation oncologists. Twenty-three (74%) patients underwent invasive mediastinal staging as part of the surgical re-evaluation after receiving definitive radiation but prior to lobectomy.

Salvage Lobectomy

Median time from radiation to lobectomy was 17.7 weeks (range, 7.6 to 111.4 weeks). Thirty patients underwent lobectomies and 1 patient underwent bilobectomy. Six patients underwent a VATS approach with no conversions and 25 patients underwent an open approach. Five patients required chest wall resection with reconstruction and 1 patient required pulmonary arterioplasty and venoplasty. Mediastinoscopy was performed at the same operation along with lobectomy in 15 patients. Mediastinal lymph node dissection was routinely performed, though in 9 patients (29%) at least one nodal station was noted to have minimal nodal tissue present, likely secondary to fibrosis from the radiation. Eleven of 31 lung resections were paired with a vascularized flap procedure to bolster the bronchial stump, including 3 serratus and 8 intercostal muscle flaps.

Perioperative outcomes are detailed in Table 5. Perioperative complications were observed in 15 of 31 (48%) patients; there were no perioperative deaths. Major complications occurred in 5 (16%) of patients, and are described below: 1) One patient underwent a right upper lobectomy that required primary repair of the pulmonary artery and vein after the stapler did not fire during specimen removal. This patient developed atrial fibrillation on post-op day 4 which was managed with diltiazem and discharged on post-operative day 6 without any further complications. 2) One patient underwent left lower lobectomy whose immediate postoperative course was unremarkable. However, on post-operative day 3, the patient was found to have a hemothorax which required thoracotomy and evacuation of a hematoma. No active bleeding was noted upon removal of hematoma and patient had no further complications. 3) Three patients developed pneumonia that was treated with antibiotics.

Table 5.

Perioperative Outcomes

| Complication | No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Overall morbidity1 | 15 (48) |

| Postoperative bleeding requiring transfusion (%) | 3 (10) |

| Postoperative bleeding requiring reoperation (%) | 1 (3) |

| Pneumonia (%) | 4 (13) |

| Atrial fibrillation (%) | 4 (13) |

| Median chest tube duration (range, days) | 3 (1-49) |

| Prolonged air leak (%) | 3 (10) |

| Other complications (%) | 0 (0) |

| Median length of hospitalization (range, days) | 4 (2-18) |

| Mortality (%) | 0 (0) |

At least one complication occurred in 15 of 31 patients. More than one complication occurred in 2; thus, itemized morbid events add up to more than 45%.

Pathologic stage and tumor response to therapy are detailed in Table 4. Complete R0 resection was achieved in 30 patients (97%). A positive bronchial margin was identified in 1 patient (3%). Viable tumor cells confirming pathologic proof of residual or recurrent disease were identified in 19 specimens (61%). The proportion of patients in each group with viable tumor present in the resection specimen was as follows: patients with obvious relapse, 3 of 3; patients felt to be initially medically inoperable, 3 of 5; and patients with residual disease by radiographic imaging, 13 of 23. Of the 12 patients who did not have viable tumor on final pathology, 11 had a residual mass on CT or residual PET activity in the primary tumor location while 1 patient was in the initially medically inoperable group and did not undergo repeat imaging following definitive radiation.

Table 4.

Tumor Characteristics

| No. of Patients | % All Patients | |

|---|---|---|

| Pathologic Stage | ||

| CR (T0N0) | 12 | 39 |

| IA | 4 | 13 |

| IB | 4 | 13 |

| IIA | 1 | 3 |

| IIB | 5 | 16 |

| IIIA | 2 | 6 |

| IIIB | 0 | 0 |

| IV | 3 | 10 |

| Post Treatment Tumor Stage | ||

| T0 (CR) | 12 | 39 |

| T1a | 6 | 19 |

| T1b | 1 | 3 |

| T2a | 5 | 16 |

| T2b | 0 | 0 |

| T3 | 6 | 19 |

| T4 | 1 | 3 |

| Post Treatment Node Stage | ||

| N0 | 28 | 90 |

| N1 | 2 | 6 |

| N2 | 1 | 3 |

| Histology | ||

| Adenocarcinoma | 8 | 26 |

| Adenosquamous | 1 | 3 |

| Squamous | 8 | 26 |

| Large Cell | 1 | 3 |

| No Tumor | 6 | 19 |

| NSCLC NOS | 7 | 23 |

| Tumor size (post treatment) | ||

| 0 to 0.5 cm | 17 | 55 |

| 0.5 to 2.5 cm | 0 | 0 |

| 2.5 to 3.5 cm | 8 | 26 |

| > 3.5 cm | 6 | 19 |

| Downstaging | ||

| Overall Downstaged | 21 | 68 |

| Downstaged from N2/N3 (n=23) to N0/N1 | 17 | 74 |

Pathological nodal status for the 31 patients was N0 in 28 (90%), N1 in 2 (6%), and N2in 1 (3%).For the patient with residual N2 disease (level 5), a mediastinoscopy had been performed after definitive radiation but prior to lobectomy, which was negative for disease in stations 4R, 4L, and 7.

Oncologic Outcomes

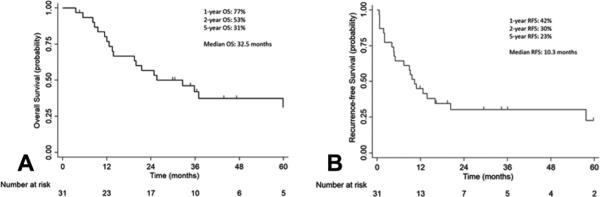

Figure 1 shows the overall and recurrence-free survival for the entire cohort after a median follow up of 26 months. Median overall survival for the entire cohort was 32.5 months, and the median follow-up for survivors was 40 months (range, 4 to 153 months). The 1-, 2- 3 and 5-year survival was 77%, 53%, 42% and 31%, respectively.

Figure 1.

Overall survival (OS) (A) and recurrence-free survival (RFS) (B) of patients undergoing lobectomy following definitive radiation.

The 1-, 2-, 3- and 5-year recurrence-free survival was 45%, 30%, 30%, 23% respectively. The first site of recurrence was locoregional recurrence only (n=4), distant recurrence only (n=7), and both local and distant recurrence (n=2). A Cox proportional hazards model evaluating age, gender, clinical stage and presence of residual disease showed that presence of residual disease was associated with worse survival (HR, 3.57; 95% CI: 1.02-12.5; p=0.047). Ten of 31 patients (32%) were still alive at last contact, and 9 of these patients were disease-free. Among these 10 survivors, 4 had viable tumor within the surgical specimen.

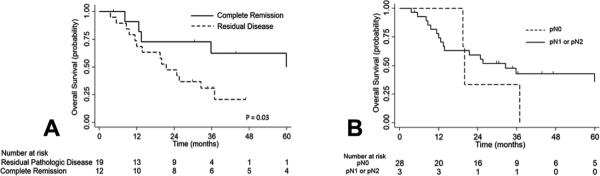

Figure 2 shows survival stratified by whether the patients had any residual disease (Fig. 2A), as well as by whether there was residual nodal disease (Fig. 2B). The 12 patients with complete pathologic response had improved median overall survival when compared to patients who still had residual pathologic disease (67% vs 31%, p=0.03) (Fig. 2A). The 5-year survival of the three patients with pathologic nodal disease was 0%, compared to 36% for patients with node negative disease after therapy (p=0.40) (Fig. 2B). Among the 12 patients with complete pathologic response, 5 patients eventually died after surgery: two patients died presumably of metastatic disease (adrenal and brain), two patients had locoregional recurrence and one had no recurrence, with exact cause of death unknown. Among the patients with residual disease, two patients with residual N1 disease survived for 16 months and 20 months, respectively. The one patient who had residual N2 disease had disease in level 5 with a left upper lobe tumor, and was found to have liver metastases two months after lobectomy that was treated with chemotherapy followed by a right hepatectomy with ultimate survival of 37 months.

Figure 2.

A) Overall survival of patients stratified by response to therapy (residual pathologic disease vs complete remission). B) Overall survival of patients with pN0 vs patients with pN1 or pN2 disease.

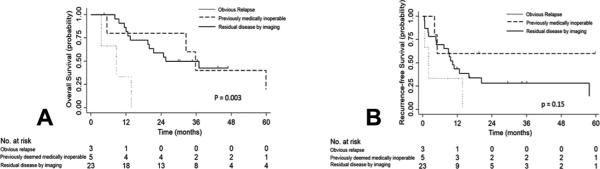

Figure 3 shows survival stratified by indication for surgery. Median overall survival was 9 months for patients with disease relapse (with none surviving for more than 14 months), 36 months for patients who were initially medically inoperable, and 26 months for patients with residual disease (Fig. 3A). Median recurrence-free survival was 10 months for the entire cohort, 2 months for patients with obvious relapse, had not been reached for patients who were initially medically inoperable, and was 10 months for patients with residual disease (Fig. 3B). Surgical indication was predictive of survival by log-rank comparison (p=0.003).

Figure 3.

Overall survival (A) and recurrence-free survival (B) by indication of surgery.

Comment

This study of 31 NSCLC patients demonstrates that lobectomy can be performed after curative-intent definitive radiation with acceptable operative mortality and morbidity (0% and 48%, respectively). Although 15 (48%) patients had perioperative complications, there were no postoperative bronchopleural fistulas and only 5 (16%) had major complications. Perioperative mortality was 0%. The five-year survival after lobectomy for this entire cohort was 31%. Patients who exhibited a complete pathologic response with no evidence of viable tumor at resection had improved overall survival. Patients with residual nodal disease did poorly, as none survived more than 37 months. Lastly, patients who underwent salvage lobectomy due to obvious relapse did particularly poorly, as none survived more than 14 months.

The predominant reason why patients were not initially offered surgery was because of apparent extent of residual disease based on preoperative evaluation (n=21). However, only 8 (38%) of these patients had invasive mediastinal staging prior to definitive radiation to confirm the presumed extent of disease. Furthermore, for our entire cohort, a surgeon participated in only 35% of staging and treatment evaluations. Given that these patients were ultimately deemed resectable, more in-depth pre-therapy evaluations may have changed the ultimate treatment regimen. Our data suggest that all patients with locally advanced NSCLC without obvious distant metastases should be very carefully evaluated in a multidisciplinary setting where medical oncology, radiation oncology and thoracic surgery discuss the plan for the patient together.

Surgical resection in the salvage setting is typically delayed beyond 2 months after high-dose curative-intent radiation treatment. In our experience the median time from the end of radiation to operation was 17.7 weeks, with resection occurring as late as 111 weeks. Because of the increased time interval between completion of radiation treatment and operation, the fibrotic response is theoretically more developed [3]. In practice, operating on fibrotic lung with brittle, devascularized tissue and obliterated planes can result in increased intraoperative risk to major vessels and further increase the risk of bronchopleural fistula due to impaired wound healing[3]. However, our experience supports reports from other institutions that have shown surgery can be safely performed in this situation. Our oncologic outcomes and complication rate of 48% are comparable to previous studies that have examined salvage resection [3, 4, 6]. Of note, in our series, only 1 patient required intra-operative major vessel repair due to stapler malfunction and there were no bronchopleural fistulas and no perioperative deaths.

The following measures are used at our institution to minimize perioperative complications. Avoidance of pneumonectomy, if possible, and particularly in patients with persistent N2 disease. Proximal pulmonary artery control is routinely obtained when hilar dissection is difficult. The bronchial stump is also routinely covered with intercostal or serratus muscle, and pleural tents and decortications are used to minimize postoperative space issues. Smoking cessation is mandated, appropriate nutrition is emphasized, and patients undergo formal or informal pulmonary rehabilitation if they have low activity levels. Because the left recurrent laryngeal nerve is frequently at risk for injury during dissection of post-radiation level 5 and 6 lymph nodes, left-sided resection patients are closely assessed before resuming oral intake, with a very low threshold to involve formal speech pathology evaluation and early vocal cord medialization when necessary.

It is notable that 12 patients in this cohort did not have pathologic disease after resection. Avoiding surgery in patients who truly do not have persistent or recurrent disease is ideal, but currently there is no definitive way to confirm pathologic complete response pre-resection. PET and CT have significant false-negative and false positives rates [17, 18]. Surgeons must use clinical judgment when biopsies do not confirm disease in the setting of suspicious radiology studies. At our institution, surgical resection is only pursued in this situation when the pattern of radiologic studies is felt to strongly suggest disease and lobectomy will clearly allow complete resection.

This study has several limitations. First, this is a retrospective single-institution series with a heterogeneous patient population who received their chemoradiation or radiation treatment at our institution or at an outside institution. Patients were referred to our institution at different time points after their initial treatment and underwent surgical salvage lobectomy in a non-standardized fashion. The study is subject to the common limitations related to its retrospective nature. Further, because of the small sample size in our study, the results should be interpreted with caution.

In conclusion, patients with advanced stage NSCLC should undergo thorough evaluation in a multidisciplinary team setting prior to undergoing definitive radiation. We have demonstrated that salvage lobectomy after curative-intent definitive radiation for NSCLC is technically feasible when indicated, with acceptable perioperative and long-term outcomes. Surgery for patients with persistent nodal disease after definitive radiation should be considered very carefully, as cure after resection may be unlikely.

Acknowledgments

Grant support included the NIH funded Cardiothoracic Surgery Trials Network, 5U01HL088953-05 (MFB), the American College of Surgeons Resident Research Scholarship (CJY), and a Medical Scientist Training Program NSRA T32GM007171 (RRM).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Ettinger DS, Akerley W, Borghaei H, et al. Non-small cell lung cancer. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2012;10:1236–1271. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2012.0130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Auperin A, Le Pechoux C, Rolland E, et al. Meta-analysis of concomitant versus sequential radiochemotherapy in locally advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:2181–2190. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.26.2543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bauman JE, Mulligan MS, Martins RG, et al. Salvage lung resection after definitive radiation (>59 Gy) for non-small cell lung cancer: surgical and oncologic outcomes. Ann Thorac Surg. 2008;86:1632–1638. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2008.07.042. discussion 1638-1639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kuzmik GA, Detterbeck FC, Decker RH, et al. Pulmonary resections following prior definitive chemoradiation therapy are associated with acceptable survival. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2013;44:e66–70. doi: 10.1093/ejcts/ezt184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Albain KS, Swann RS, Rusch VW, et al. Radiotherapy plus chemotherapy with or without surgical resection for stage III non-small-cell lung cancer: a phase III randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2009;374:379–386. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60737-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen F, Matsuo Y, Yoshizawa A, et al. Salvage lung resection for non-small cell lung cancer after stereotactic body radiotherapy in initially operable patients. J Thorac Oncol. 2010;5:1999–2002. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e3181f260f9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hishida T, Nagai K, Mitsudomi T, et al. Salvage surgery for advanced non-small cell lung cancer after response to gefitinib. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2010;140:e69–71. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2010.06.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Takamochi K, Suzuki K, Sugimura H, et al. Surgical resection after gefitinib treatment in patients with lung adenocarcinoma harboring epidermal growth factor receptor gene mutation. Lung Cancer. 2007;58:149–155. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2007.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mogi A, Kosaka T, Yamaki E, Kuwano H. Successful resection of stage IV non-small cell lung cancer with muscle metastasis as the initial manifestation: a case report. Ann Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2012;18:468–471. doi: 10.5761/atcs.cr.11.01798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fowler WC, Langer CJ, Curran WJ, Jr., Keller SM. Postoperative complications after combined neoadjuvant treatment of lung cancer. Ann Thorac Surg. 1993;55:986–989. doi: 10.1016/0003-4975(93)90131-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cerfolio RJ, Bryant AS, Jones VL, Cerfolio RM. Pulmonary resection after concurrent chemotherapy and high dose (60Gy) radiation for non-small cell lung cancer is safe and may provide increased survival. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2009;35:718–723. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2008.12.029. discussion 723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kwong KF, Edelman MJ, Suntharalingam M, et al. High-dose radiotherapy in trimodality treatment of Pancoast tumors results in high pathologic complete response rates and excellent long-term survival. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2005;129:1250–1257. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2004.12.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sonett JR, Suntharalingam M, Edelman MJ, et al. Pulmonary resection after curative intent radiotherapy (>59 Gy) and concurrent chemotherapy in non-small-cell lung cancer. Ann Thorac Surg. 2004;78:1200–1205. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2004.04.085. discussion 1206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Suntharalingam M, Paulus R, Edelman MJ, et al. Radiation therapy oncology group protocol 02-29: a phase II trial of neoadjuvant therapy with concurrent chemotherapy and full-dose radiation therapy followed by surgical resection and consolidative therapy for locally advanced non-small cell carcinoma of the lung. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2012;84:456–463. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2011.11.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Edge SB, American Joint Committee on Cancer., American Cancer Society . AJCC cancer staging handbook : from the AJCC cancer staging manual. Springer; New York: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang H, D'Amico TA. Efficacy of mediastinal lymph node dissection during thoracoscopic lobectomy. Ann Cardiothorac Surg. 2012;1:27–32. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2225-319X.2012.04.02. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bunyaviroch T, Coleman RE. PET evaluation of lung cancer. J Nucl Med. 2006;47:451–469. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee HY, Lee HJ, Kim YT, et al. Value of combined interpretation of computed tomography response and positron emission tomography response for prediction of prognosis after neoadjuvant chemotherapy in non-small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2010;5:497–503. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e3181d2efe7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]