Abstract

Background

Suicide is one of the leading causes of death in postpartum women. Identifying modifiable factors related to suicide risk in mothers after delivery is a public health priority. Our study aim was to examine associations between suicidal ideation (SI) and plausible risk factors (experience of abuse in childhood or as an adult, sleep disturbance, and anxiety symptoms) in depressed postpartum women.

Methods

This secondary analysis included 628 depressed mothers at 4–6 weeks postpartum. Diagnosis was confirmed with the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV. We examined SI from responses to the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale-EPDS item 10; depression levels on the Structured Interview Guide for the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale, Atypical Depression Symptoms (SIGH-ADS); plus sleep disturbance and anxiety levels with subscales from the EPDS and SIGH-ADS items on sleep and anxiety symptoms..

Results

Of the depressed mothers, 496 (79%) ‘never’ had thoughts of self-harm; 98 (15.6%) ‘hardly ever’; and 34 (5.4%) ‘sometimes’ or ‘quite often’. Logistic regression models indicated that having frequent thoughts of self-harm was related to childhood physical abuse (odds ratio-OR=1.68, 95% CI=1.00, 2.81); in mothers without childhood physical abuse, having frequent self-harm thoughts was related to sleep disturbance (OR=1.15, 95%CI=1.02, 1.29) and anxiety symptoms (OR=1.11, 95%CI=1.01, 1.23).

Discussion

Because women with postpartum depression can present with frequent thoughts of self-harm and a high level of clinical complexity, conducting a detailed safety assessment, that includes evaluation of childhood abuse history and current symptoms of sleep disturbance and anxiety, is a key component in the management of depressed mothers.

Keywords: suicidal ideation, postpartum depression, childhood abuse, sleep disturbance, anxiety

Introduction

Suicide is one of the leading causes of death in postpartum women (Oates, 2003). Recent findings suggest that suicide is the seventh leading cause of maternal death within 6 months of delivery (1.27 per 100,000 maternal deaths) (Lewis et al., 2011). Major depression, bipolar disorders, alcohol and substance use disorders, schizophrenia, and anxiety disorders contribute to the increased risk for suicide and suicidal behaviors (Hawton & van Heeringen, 2009) (Oquendo et al., 1997) (Rihmer et al., 1995) (Fawcett et al., 1990) (Cornelius et al., 1995) (Nepon et al., 2010) (Busch et al., 2003; Sareen et al., 2005). In the postpartum period, women with a psychiatric disorder, substance use disorder or both disorders were at significantly increased risk for suicide attempts by 27, 6 and 11-fold, respectively (Comtois et al., 2008). Of mothers who died from suicide in the first 6 months after childbirth, the primary diagnoses were severe depression in 21%, substance use disorders in 31% and psychosis in 38% (Lewis et al., 2011).

The inadequate assessment of risk or illness severity (Lewis et al., 2011) plus low rates of seeking mental health treatment (15% of postpartum women with major mood disorders)(Vesga-López et al., 2008) likely compound the risk for suicide in postpartum women (Fawcett et al., 1990; Oquendo et al., 1997). Beyond risk to mothers themselves, maternal suicidality can undermine mother-infant interactions. Mothers with suicidal symptoms display reduced responsiveness and sensitivity to infant cues; their infants have less positive affect and reduced engagement with their mothers (Paris et al., 2009).

In addition to psychiatric disorders, other risk factors for suicide or suicidal ideation (SI) in adults include a history of self-harm or suicide attempts (Cavanagh et al., 2003) (Hawton & van Heeringen, 2009), suicidal thoughts (Coryell & Young, 2005) (Fawcett et al., 1990), a family history of suicide (Brent et al., 1988) (Hawton & van Heeringen, 2009) (Oquendo et al, 1997)(Roy, 1983) and increased levels of hopelessness (Fawcett et al., 1990) (Beck et al., 1985). Experiences of childhood physical abuse, sexual abuse and neglect are significantly associated with suicide attempts and thoughts of suicide in the general community (Fuller-Thomson et al., 2012) (McCauley et al., 1997) (Dube et al., 2001) (Joiner et al., 2007) (Enns et al., 2006) and in patients with major depressive disorders (Brown et al., 1999) (Brodsky et al., 2001) (McHolm et al., 2003) (Oquendo et al., 2005) (Widom et al., 2007). Among severely depressed patients proximal risk factors for suicide and suicidal behaviors include acute intoxication (Oquendo et al., 1997), sleep disturbance (insomnia or nightmares) (Bernert et al., 2005) (Fawcett et al., 1990) and heightened symptoms of anxiety or agitation (Busch et al., 2003) (Fawcett et al., 1990).

The reduction of suicide risk in mothers with major mood disorders is a public health priority. After delivery, women with postpartum major depression, puerperal psychosis and recurrent episodes of Bipolar Disorder (BD), often had thoughts of self-harm or SI (Wisner et al., 2013) (Howard et al., 2011) (Sit et al., 2006) (Pope et al., 2013). Findings from a postpartum depression screening program of 10,000 women, indicated postpartum women who screened positive for depression had high rates of self-harm ideation (19.3%) and frequent thoughts of self-harm (3.2%)(Wisner et al., 2013). Depression screening of 4,000+ postpartum women in the community also suggested 4% had frequent thoughts of self-harm sometimes” or “quite often” (Howard et al., 2011).

To understand the risk of suicide or thoughts of self-harm in postpartum women, we can begin by exploring the known risk factors for suicide or SI in adults with and without major mood disorders. Given the compelling findings from our group (Wisner et al., 2013) and others (Howard et al., 2011; Paris et al., 2009; Pope et al., 2013), we conducted secondary analyses to determine whether the known risk factors for suicidal symptoms in adults with and without mood disorders also applied to women after childbirth. Our study aim was to examine associations between SI and plausible risk factors (trauma history i.e. the experience of abuse in childhood or as an adult, sleep disturbance, and anxiety symptoms) in depressed postpartum women. The hypothesis was the experience of childhood abuse, current sleep disturbance, and increased levels of maternal anxiety would be associated with increased thoughts of self-harm in depressed postpartum women at 4–6 weeks after childbirth.

Methods

In the earlier report, we described in detail the design and methodology of the original postpartum depression (PPD) screening study approved by the University of Pittsburgh Institutional Review Board (Wisner et al., 2013). Postpartum women were enrolled in a depression screening program based at a major obstetrical hospital (Wisner et al., 2013). On the maternity ward, nurses or social workers approached women who delivered a live infant, provided information about PPD, and offered depression screens by telephone at 4–6 weeks postpartum. Potential participants who were 18 years or older signed a waiver to give permission for the phone screen. Exclusion criteria included non-English speaking, less than 18 years old, unable to provide consent or no phone availability.

To screen for PPD, we used the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) (Cox et al., 1987). The EPDS is a brief 10-item screening measure and is the most commonly used PPD screening tool world-wide (Gibson et al., 2009). Other appealing aspects of the EPDS included the uncomplicated scoring system by simple addition, proven patient acceptability in different socioeconomic and ethnic groups (Gibson et al., 2009), and evidence of psychometric validity (Hanusa et al., 2008). Postpartum women with a depression-positive phone screen (EPDS≥10)(Cox et al., 1987) were offered an in-home evaluation to confirm the psychiatric diagnosis. At the home visit, Master’s level clinicians completed the diagnostic evaluation; the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID)(First et al., 1996) was used to confirm the primary and secondary psychiatric diagnoses (Table 1). Clinicians recorded the demographic and clinical data which included age, race, education, marital status, parity, chronic medical conditions and the time of depression onset (Table 2 and Table 3). Woman who declined the in-home evaluation were offered an assessment for PPD by telephone with the SCID criteria for MDD only.

Table 1.

Primary and secondary diagnoses for 628 randomized women.

| Primary diagnosis | N (%) | Secondary diagnosis | N (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Depressive disorders | 568 (90.4) | Primary diagnosis: Depressive disorders | 568 (90.4) |

| Major depression | 516 (90.8) | Anxiety disorders | 311 (54.7) |

| Recurrent | 373 (72.3) | Generalized anxiety disorder | 177 (56.9) |

| Single | 143 (27.7) | Posttraumatic stress disorder | 31 (10.0) |

| Depressive disorder NOS | 37 (6.5) | Panic disorder without agoraphobia | 19 (6.1) |

| Adjustment disorder with | 11 (1.9) | Panic disorder with agoraphobia | 16 (5.1) |

| depressed mood | |||

| Mood disorder NOS | 2 (0.4) | Anxiety disorder NOS | 14 (4.5) |

| Dysthymic disorder | 2 (0.4) | Social phobia | 10 (3.2) |

| Specific phobia | 9 (2.9) | ||

| Anxiety disorder | 6 (1.9) | ||

| Agoraphobia without history of panic disorder |

2 (0.6) | ||

| Depressive disorders | 26 (4.6) | ||

| Dysthymic disorder | 25 (96.2) | ||

| Major depressive disorder, recurrent | 1 (3.8) | ||

| Substance use disorders | 9 (1.6) | ||

| Alcohol abuse | 3 (33.3) | ||

| Opioid dependence | 2 (22.2) | ||

| Cannabis abuse | 1 (11.1) | ||

| Cocaine dependence | 1 (11.1) | ||

| Polysubstance dependence | 1 (11.1) | ||

| Unknown | 1 (11.1) | ||

| Other disorders | 8 (1.4) | ||

| Bulimia nervosa | 4 (50.0) | ||

| Eating disorder NOS | 2 (25.0) | ||

| Anorexia nervosa | 1 (12.5) | ||

| Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity disorder | 1 (12.5) | ||

| No comorbidity | 214 (37.7) | ||

| Anxiety disorders | 39 (6.2) | Primary diagnosis: Anxiety disorders | 39 (6.2) |

| Generalized anxiety disorder | 22 (56.4) | Depressive disorders | 16 (41.0) |

| Anxiety disorder NOS | 7 (17.9) | Major depression | 13 (81.3) |

| Obsessive-compulsive disorder | 4 (10.3) | Recurrent | 12 (93.7) |

| Adjustment disorder with anxiety | 2 (5.1) | Single | 1 (6.3) |

| Panic disorder without agoraphobia | 1 (2.6) | Depressive disorder NOS | 2 (12.5) |

| Posttraumatic stress disorder | 1 (2.6) | Dysthymic disorder | 1 (6.3) |

| Social phobia | 1 (2.6) | Anxiety disorders | 5 (12.8) |

| Specific phobia | 1 (2.6) | Social phobia | 2 (40.0) |

| Generalized anxiety disorder | 1 (20.0) | ||

| Panic disorder without agoraphobia | 1 (20.0) | ||

| Posttraumatic stress disorder | 1 (20.0) | ||

| No comorbidity | 18 (46.2) | ||

| Substance use disorders | 3 (0.5) | ||

| Opioid dependence | 3 (100) | ||

| Other disorders | 5 (0.8) | ||

| No diagnosis | 13 (2.1) |

Please note, we constructed the report from data provided by patients with unipolar disorders only; we excluded patients with bipolar disorders and psychotic disorders. We confirmed the diagnoses from data recorded at the home visit SCID interview and careful re-review of the psychiatric evaluation forms during a 2012 data cleanup initiative.

TABLE 2.

Sociodemographic measures by EPDS item 10: “The thought of harming myself has occurred to me”a

| The thought of harming myself has occurred to meb | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Totalc | Never | Hardly Ever | Sometimes/ Often |

Test statistic |

p | Pair-wise comparison | |||

| Demographic Variable |

(N = 628) | (N = 496) | (N = 98) | (N = 34) | N v H | N v S | H v S | ||

| Age | 28.7 ± 6.00 | 28.9 ± 6.04 | 28.3 ± 5.99 | 26.2 ± 4.92 | X2 (6) = 5.71 | 0.0251 | 0.303 | 0.009* | 0.071 |

| Race | X2 (4) = 16.2 | 0.0027 | 0.187 | 0.002* | 0.010* | ||||

| White | 460 (73.2) | 373 (81.1) | 71 (15.4) | 16 (3.5) | |||||

| Black | 133 (21.2) | 100 (75.2) | 18 (13.5) | 15 (11.3) | |||||

| Other | 35 (5.6) | 23 (65.7) | 9 (25.7) | 3 (8.6) | |||||

| Education (level) | X2 (8) = 8.44 | 0.3919 | |||||||

| <High school | 41 (6.5) | 31 (75.6) | 6 (14.6) | 4 (9.8) | |||||

| High school | 129 (20.5) | 96 (74.4) | 22 (17.1) | 11 (8.5) | |||||

| Some college | 199 (31.7) | 157 (78.9) | 33 (16.6) | 9 (4.5) | |||||

| College | 154 (24.5) | 122 (79.2) | 26 (16.9) | 6 (3.9) | |||||

| Graduate School | 105 (16.7) | 90 (85.7) | 11 (10.5) | 4 (3.8) | |||||

| Medical insurance | P < 0.01 | 0.0223 | 0.117 | 0.034 | 0.053 | ||||

| Private | 353 (56.2) | 286 (81.0) | 55 (15.6) | 12 (3.4) | |||||

| Public | 269 (42.8) | 207 (77.0) | 40 (14.9) | 22 (8.2) | |||||

| None | 6 (1.0) | 3 (50.0) | 3 (50.0) | 0 (0.0) | |||||

| Marital status | P < 0.01 | 0.0686 | |||||||

| Single | 266 (42.4) | 199 (74.8) | 46 (17.3) | 21 (7.9) | |||||

| Married/cohabiting | 349 (55.6) | 287 (82.2) | 50 (14.3) | 12 (3.4) | |||||

| Divorced/separated | 13 (2.1) | 10 (76.9) 1.02 ± |

2 (15.4) | 1 (7.7) | |||||

| Parity (1 or >1) | 1.03 ± 1.11 | 1.08 | 1.04 ± 1.29 | 1.03 ± 0.94 | H(2) = 0.69 | 0.7094 | |||

| Parity | X2(6) = 5.71 | 0.4565 | |||||||

| 0 | 235 (37.4) | 182 (77.4) | 43 (18.3) | 10 (4.3) | |||||

| 1 | 238 (37.9) | 192 (80.7) | 30 (12.6) | 16 (6.7) | |||||

| 2 | 96 (15.3) | 77 (80.2) | 13 (13.5) | 6 (6.3) | |||||

| 3+ | 59 (9.4) | 45 (76.3) | 12 (20.3) | 2 (3.4) | |||||

Descriptive statistics presented as mean ± SD, n (%N).

Item 10 of the Edinburgh postnatal depression scale.

Total column n is the denominator for percentages in “Never”, “Hardly ever”, and “Sometimes”/”Quite often” columns.

Significant after Bonferroni correction.

Table 3.

Clinical measures by Response to EPDS Item 10

| The thought of harming myself has occurred to me | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Never | Hardly | Sometimes/ Often |

Test statistic | p | Pair-wise comparison | ||||

| Clinical Variable | (N = 628) | (N = 496) | (N = 98) | (N = 34) | N v H | N v S | H v S | |||

| Primary diagnosis | P < 0.01 | 0.9524 | ||||||||

| Depressive Disorders | 568 (90.4) | 446 (78.5) | 90 (15.8) | 32 (5.6) | ||||||

| Anxiety Disorders | 39 (6.2) | 32 (82.1) | 6 (15.4) | 1 (2.6) | ||||||

| Substance use | 3 (0.5) | 3 (100) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | ||||||

| Other | 5 (0.8) | 4 (80.0) | 1 (20.0) | 0 (0.0) | ||||||

| None | 13 (2.1) | 11 (84.6) | 1 (7.7) | 1 (7.7) | ||||||

| # comorbid psychiatric diagnoses | 1.01 ± 1.07 | 0.96 ± 1.04 | 1.32 ± 1.18 | 1.00 ± 1.02 | H(2) = 8.21 | 0.0165 | 0.004* | 0.722 | 0.199 | |

| Physically abused as a child | X2(2) = 5.99 | 0.0501 | ||||||||

| Yes | 102 (16.6) | 73 (71.6) | 19 (18.6) | 10 (9.8) | ||||||

| No | 514 (83.4) | 413 (80.4) | 78 (15.2) | 23 (4.5) | ||||||

| Sexually abused as a child | X2(2) = 0.49 | 0.7827 | ||||||||

| Yes | 129 (20.9) | 99 (76.7) | 22 (17.1) | 8 (6.2) | ||||||

| No | 487 (79.1) | 387 (79.5) | 75 (15.4) | 25 (5.1) | ||||||

| Physically abused as an adult | X2(2) = 0.16 | 0.9236 | ||||||||

| Yes | 186 (30.2) | 147 (79.0) | 30 (16.1) | 9 (4.8) | ||||||

| No | 430 (69.8) | 339 (78.8) | 67 (15.6) | 24 (5.6) | ||||||

| Sexually abused as an adult | X2(2) = 3.52 | 0.172 | ||||||||

| Yes | 68 (11.0) | 49 (72.1) | 16 (23.5) | 3 (4.4) | ||||||

| No | 548 (89.0) | 437 (79.7) | 81 (14.8) | 30 (5.5) | ||||||

| Onset of current episode | X2(4) = 11.8 | 0.019 | 0.814 | 0.003* | 0.016* | |||||

| Pre-pregnancy | 213 (33.9) | 162 (76.1) | 32 (15.0) | 19 (8.9) | ||||||

| Pregnancy | 280 (44.6) | 231 (82.5) | 43 (15.4) | 6 (2.1) | ||||||

| Post-partum | 135 (21.5) | 103 (76.3) | 23 (17.0) | 9 (6.7) | ||||||

| N chronic medical conditions | 3.19±2.13 | 3.13 ± 2.10 | 3.59 ± 2.31 | 2.89 ± 1.94 | H(2) = 2.88 | 0.2364 | ||||

| SIGH-ADS29 | 19.6±6.23 | 19.3 ± 6.10 | 20.5 ± 6.50 | 21.1 ± 6.97 | F(2,625) = 2.61 | 0.074 | ||||

| Sum of SIGH-ADS29 insomnia items1 | 2.39 ±1.38 | 2.39 ± 1.35 | 2.37 ± 1.47 | 2.50 ± 1.56 | H(2) = 0.17 | 0.9187 | ||||

| Disturbed sleep symptoms subscale2 | 4.67 ±1.93 | 4.57 ± 1.86 | 4.82 ± 2.02 | 5.65 ± 2.29 | F(2,625) =3.71 | 0.0050 | 0.247 | 0.001* | 0.048 | |

| Sum of SIGH-ADS29 anxiety items3 |

5.15 ±1.83 | 5.15 ± 1.82 | 5.18 ± 1.86 | 5.12 ± 1.92 | F(2,595) = 0.02 | 0.9790 | ||||

| Anxiety symptoms subscale4 | 7.45 ± 2.24 | 7.35 ± 2.23 | 7.78 ± 2.27 | 7.91 ± 2.23 | F(2,625) = 2.23 | 0.1087 | ||||

| GAF | 60.7±6.92 | 61.2 ± 6.92 | 58.8 ± 6.49 | 59.0 ± 7.09 | F(2,625) = 5.77 | 0.0033 | 0.002* | 0.088 | 0.836 | |

Abbreviations GAF Global assessment of Function; SIGH-ADS Structured interview guide for the Hamilton rating scale for depression with atypical depression supplement.

SIGH-ADS Sleep symptoms = early, middle and late insomnia (items H6, H7 and H8, respectively), hypersomnia (item A6) and WASO>20 minutes.

Disturbed sleep 6-point composite subscale = five SIGH-ADS Sleep items plus EPDS item 7 “I’ve been so unhappy I’ve had difficulty sleeping”

SIGH-ADS Anxiety items = agitation, psychic anxiety, somatic symptoms, hypochondriasis and obsessive thoughts or compulsive behaviors (items H17, H12, H13, H14 and H21 respectively)

Anxiety 7-point composite subscale = SIGH-ADS Anxiety items plus EPDS items 4 and 5 for symptoms of “I’ve been anxious or worried for no good reason and “I’ve felt scared or panicky for no very good reason”, respectively.

Significant after Bonferroni correction.

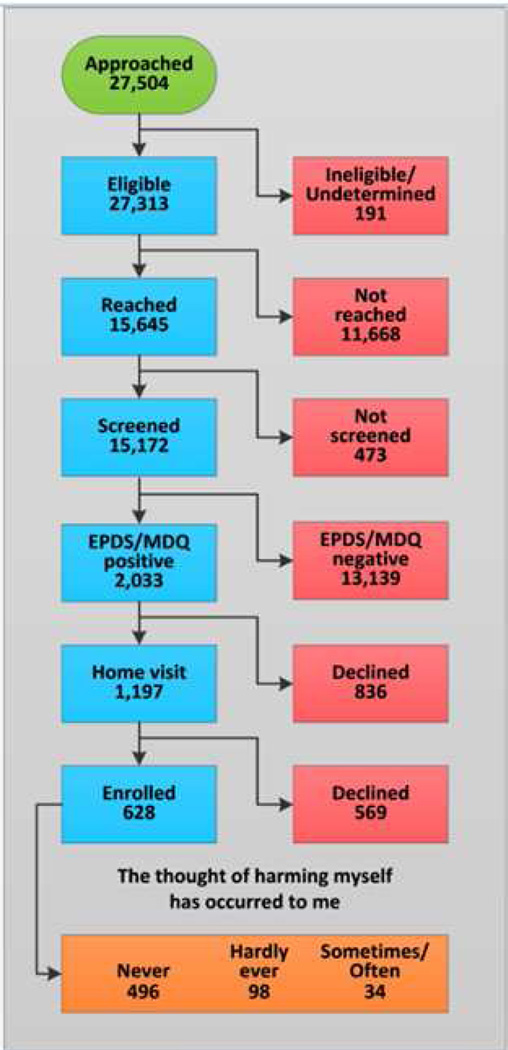

Study Participants (Figure 1)

Figure 1.

Consort Diagram: Study Flow.

For this secondary analysis, we included depressed postpartum women who were enrolled in the primary study (R01 MH 071825 for Identification and Therapy of Postpartum Depression; PI: Dr. Wisner). Study participants had a SCID-confirmed primary diagnosis of a current major depressive disorder (Hawton & van Heeringen, 2009) or anxiety disorder (Sareen et al., 2005). The primary study was designed to examine the outcomes of unipolar major depression in women during the first postpartum year. We completed the SCID interview to confirm diagnosis on all potential study patients and the clinical assessments of depression levels, anxiety symptoms and sleep disturbance only on the eligible patients with unipolar major postpartum depression. Patients with Bipolar Disorders and primary psychotic disorders were excluded because they were ineligible for the primary study and did not provide a complete set of clinical data for the required analyses.

Thoughts of Self-Harm

To evaluate self-harm ideation, we examined item 10 of the EPDS (presented as “The thought of harming myself has occurred to me”). Possible responses included ‘never’=0, ‘hardly ever’=1, ‘sometimes’=2, or ‘quite often’=3. Women who had high scores (EPDS≥20) or any thoughts of self-harm (EPDS item 10 ≥ 1) were interviewed immediately by the supervising clinician to assess for safety and to develop an emergency intervention.

Abuse History

To define exposures to childhood and adult physical and sexual abuse, we inquired with standardized questions from the Dissociative Disorders Interview Schedule (DDIS) (Ross et al., 1989) which included the following items: As an adult, have you ever been hit, slapped, kicked or otherwise physically hurt by someone? As an adult, have you ever been forced to have an unwanted sexual act? Were you physically abused as a child or adolescent? Were you sexually abused as a child or adolescent? The inquiry provided dichotomous (yes/no) responses that were used to quantify the frequencies of each of the abuse exposures. Clinicians specifically explored for abuse history as part of an evaluation of patient safety, the risk for interpersonal violence, and other risks for comorbid disorders related to depressive disorders including post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Abuse history was obtained by empathic inquiry into the patient’s experience of physical abuse or sexual abuse in childhood or adulthood. Patients who reported the experience of current or past abuse were offered referral to appropriate community programs.

Sleep disturbance and anxiety symptoms

In the evaluation of depression severity, clinicians rated the Structured Interview Guide for the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression, Atypical Depression Symptoms Version (SIGH-ADS)(Williams & Terman, 2003), a 29-item instrument that incorporates the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HRSD)(Hamilton, 1960) and a set of questions to explore neuro-vegetative symptoms. We examined overall functioning from clinical scores on the Global Assessment of Function (GAF). Because symptoms of disturbed sleep and anxiety can represent distinct subtypes of major depression (Moritz et al., 2004),(Fawcett et al., 1990) and substance use disorders (Clark et al., 2001), we examined sleep disturbance and maternal anxiety subscales (Moritz et al., 2004),(Fawcett et al., 1990) from the SIGH-ADS and EPDS measures. For sleep disturbance we examined the SIGH-ADS sleep items on early, middle and late insomnia (items H6, H7 and H8), hypersomnia (item A6) and wake time after sleep onset (WASO) more than 20 minutes. We constructed a categorical measure of insomnia (score of 2 on any of the 3 insomnia items), and a composite 6-point subscale for sleep (Clark et al., 2001; Fawcett et al., 1990) comprised of the SIGH-ADS sleep items plus EPDS item 7 “I’ve been so unhappy I’ve had difficulty sleeping”. We explored maternal anxiety symptoms (Wisner et al., 2013) with the SIGH-ADS items for anxiety: agitation, psychic anxiety, somatic symptoms, hypochondriasis and obsessive thoughts or compulsive behaviors (items H17, H12, H13, H14, and H21), and a composite 7-point anxiety subscale (Clark et al., 2001; Fawcett et al., 1990; Moritz et al., 2004) comprised of the SIGH-ADS anxiety items plus EPDS items 4 and 5, “I’ve been anxious or worried for no good reason and “I’ve felt scared or panicky for no very good reason”.

Outcome Measures and Statistical Analysis

We compared outcomes of three groups of patients based on their EPDS item 10 scores as follows: 0=‘never’, 1=‘hardly ever’ and 2 or 3=‘sometimes’ or ‘quite often’. To examine group differences on demographic characteristics, clinical history, depression severity, anxiety symptoms and sleep disturbance, we used analysis of variance (ANOVA) for normally-distributed data from the continuous measures and the non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis test, otherwise. For categorical measures, we used the Pearson’s chi-square test or Fisher’s Exact test depending on expected cell sizes. We investigated associations between thoughts of self-harm and history of abuse (physical or sexual abuse experience as a child or adult), sleep disturbance (in the past seven days), anxiety levels, and the interaction between abuse history and sleep disturbance or anxiety levels with cumulative logistic regression models. The cumulative logistic regression models comprised of bivariate models in which the outcome measures, frequency of thoughts of self-harm (never, rarely, sometimes/quite often), were stratified by the specified abuse measure, experience of past physical or sexual abuse as a child or adult, and regressed onto the measures of anxiety symptoms and sleep disturbance. To examine interaction effects between anxiety symptoms, sleep disturbance and experience of the specified abuse, we used multivariate models. With backward stepwise logistic regressions, we explored potential predictors for between group differences (including age, race, parity, insurance, marital status, education, number of psychiatric or chronic medical conditions, time of illness onset, depression severity, anxiety symptoms, sleep disturbance, abuse history, and global functioning), and appropriately eliminated variables which were not significant. We corrected for repeated testing with the Bonferroni method.

Results

Patient Characteristics

The study patients included 628 women with a positive depression screen (EPDS≥10) and a SCID-confirmed diagnosis of a primary depressive or anxiety disorder (Figure 1 – consort chart). The vast majority of patients had depressive disorders (568/628, 90.4%) of whom most had major depressive disorder (516/568, 90.4%), either recurrent (373/516, 72.3%) or single episodes (143/516, 27.7%); 39 had depressive or mood disorder NOS; and 13 had either an adjustment disorder with depressed mood or dysthymic disorder. Of the patients with primary depressive disorders, more than one-half had secondary anxiety disorders (311/568), which included generalized anxiety disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder, panic disorders, and social or specific phobias. Six percent (39/568) of the enrolled participants had a primary anxiety disorder, of whom more than one-half (22/39, 56.4%) had generalized anxiety disorder and the others had various DSM-IV anxiety disorders (Table 1).

Of the enrolled mothers, 496 (77%) reported they ‘never’ had thoughts of self-harm; 98 (15%) reported ‘hardly ever’; and 34 (5%), ‘sometimes’ or ‘quite often’. The racial distribution differed significantly across groups: 11.3% (15/133) of African American compared to 3.5% (16/460) of white mothers reported thoughts of self-harm ‘sometimes’ or ‘quite often’ (X2 (4) = 16.2; p=0.003) (Table 2). Having frequent self-harm thoughts ‘sometimes’ or ‘quite often’ was more common in mothers who received public (22/269, 8.2%) compared to private insurance (12/353, 3.4%, P<0.01; p=0.02). Differences in the access to insurance were non-significant after Bonferroni correction.

Compared to mothers who ‘never’ had thoughts of self-harm, mothers who ‘hardly ever’ had thoughts of self-harm had significantly more psychiatric comorbidities (including anxiety, substance use or eating disorders; H[2]=8.21; p<.02) and a significantly reduced level of functioning (F[2,625]=5.77; p<.01) (Table 3). Time of illness onset was significantly associated with frequent thoughts of self-harm (X2 (4) = 11.8; p=0.02). A higher percentage of mothers with the onset of depression before pregnancy (19/213, 8.9%) or after delivery (9/135, 6.7%) had self-harm thoughts ‘sometimes or ‘quite often’ compared to mothers with pregnancy-onset depression (6/280, 2.1%)(Table 3). Having thoughts of self-harm ‘sometimes’ or ‘quite often’ was reported significantly more frequently by patients who had increased sleep disturbance (F(2,625) =3.71; p=0.0050)(Table 3). On the other hand, mean levels of depression and anxiety symptoms (Table 3) did not differ across groups. In backward stepwise regressions the remaining predictor was global functioning.

The rates of childhood physical and sexual abuse were 16.6% (102/616) and 20.9% (129/616), respectively. As adults, 30.2% (186/616) of mothers suffered physical abuse and 11.0% (68/616), sexual abuse (Table 3). Although women who experienced childhood physical abuse were more than twice as likely to have thoughts of self-harm ‘sometimes’ or ‘quite often’ (10/102, 9.8%) compared to mothers who did not experience physical abuse as children (23/514, 4.5%), the difference was not significant in the between-group comparisons (Table 3). The frequency of self-harm thoughts did not differ among women with/without childhood sexual abuse, or physical or sexual abuse as adults.

Half of the patients reported no abuse history (Table 5). Many participants reported experiencing multiple forms of abuse (physical or sexual abuse as a child or adult); 20.5% (128/616) experienced two or more forms of abuse; 27.6% (170/616), one form of abuse; and 52% (318/616), had no lifetime abuse experience. In mothers who reported two (n=82) or three (n=33) forms of abuse, 22 and 24% had infrequent thoughts of self-harm and 6 and 12% had frequent self-harm thoughts. Of the patients who experienced physical abuse in childhood, 73% experienced abuse in one or more of the other abuse categories examined in the study; similarly almost 70% of patients with exposure to childhood sexual abuse also experienced abuse in another category (Table 5).

Table 5.

The Frequency and Cumulative Frequency of exposures to abuse as a child and adult.

| PhysAb* Child |

SexualAb* Child |

PhysAb Adult |

SexualAb Adult |

Frequency | Percent | Cumulative Frequency |

Cumulative Percent |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ms | ms | ms | ms | 12 | 1.91 | 12 | 1.91 |

| Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 13 | 2.07 | 25 | 3.98 |

| Yes | Yes | Yes | No | 17 | 2.71 | 42 | 6.69 |

| Yes | Yes | No | Yes | 3 | 0.48 | 45 | 7.17 |

| Yes | Yes | No | No | 19 | 3.03 | 64 | 10.19 |

| Yes | No | Yes | Yes | 5 | 0.80 | 69 | 10.99 |

| Yes | No | Yes | No | 15 | 2.39 | 84 | 13.38 |

| Yes | No | No | Yes | 1 | 0.16 | 85 | 13.54 |

| Yes | No | No | No | 29 | 4.62 | 114 | 18.15 |

| No | Yes | Yes | Yes | 8 | 1.27 | 122 | 19.43 |

| No | Yes | Yes | No | 23 | 3.66 | 145 | 23.09 |

| No | Yes | No | Yes | 3 | 0.48 | 148 | 23.57 |

| No | Yes | No | No | 43 | 6.85 | 191 | 30.41 |

| No | No | Yes | Yes | 21 | 3.34 | 212 | 33.76 |

| No | No | Yes | No | 84 | 13.38 | 296 | 47.13 |

| No | No | No | Yes | 14 | 2.23 | 310 | 49.36 |

| No | No | No | No | 318 | 50.64 | 628 | 100.00 |

Abbreviations. ms = missing; PhysAb = Physical Abuse; SexualAb = Sexual Abuse.

Cumulative logistic regression models indicated only a significant main effect of childhood physical abuse on risk for thoughts of self-harm (odds ratio-OR=1.677 95% confidence interval–CI =1.002, 2.809, Wald X2=3.87; p<0.05). The experience of more than one form of abuse was not associated with increased odds for having thoughts of self-harm. In mothers with no history of childhood physical abuse, an increased risk for self-harm thoughts associated with sleep disturbance (OR= 1.148, 95%CI=1.024, 1.286, p=0.0176) and maternal anxiety symptoms (OR=1.114, 95%CI= 1.009, 1.230, p=0.033) was observed in the bivariate models (Table 4). After stratifying for with or without the specified abuse history, the multivariate models which included sleep disturbance and anxiety symptoms indicated no significant interaction effects on thoughts of self-harm.

Table 4.

Odds ratios, 95% confidence intervals, and probability values from cumulative logistic models of EPDS item 10: “The thought of harming myself has occurred to me” regressed on anxiety/disturbed sleep symptoms stratified by abuse measure, and the interaction between anxiety/disturbed sleep symptoms and abuse measure.

| Main effect of symptoms (anxiety or disturbed sleep) when specified abuse is present |

Main effect of symptoms (anxiety or disturbed sleep) when specified abuse is absent |

Interaction between symptoms & abuse |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measure | N | OR | 95% CI | p | N | OR | 95% CI | p | N | p |

| Anxiety symptoms | ||||||||||

| Physical abuse as a child |

102 | 1.011 | (0.844, 1.211) |

0.9088 | 514 | 1.114 | (1.009, 1.230) |

0.0327 | 616 | 0.3565 |

| Sexual abuse as a child |

129 | 1.093 | (0.920, 1.298) |

0.3112 | 487 | 1.090 | (0.986, 1.205) |

0.0937 | 616 | 0.9767 |

| Physical abuse as an adult |

186 | 1.147 | (0.964, 1.365) |

0.1215 | 430 | 1.077 | (0.973, 1.191) |

0.1526 | 616 | 0.5423 |

| Sexual abuse as an adult |

68 | 0.980 | (0.768, 1.250) |

0.8723 | 548 | 1.106 | (1.007, 1.214) |

0.0348 | 616 | 0.3691 |

|

Symptoms of sleep disturbance |

||||||||||

| Physical abuse as a child |

102 | 1.041 | (0.844, 1.284) |

0.7080 | 511 | 1.148 | (1.024, 1.286) |

0.0176 | 613 | 0.4313 |

| Sexual abuse as a child |

129 | 1.043 | (0.858, 1.268) |

0.6734 | 484 | 1.161 | (1.033, 1.305) |

0.0122 | 613 | 0.3572 |

| Physical abuse as an adult |

184 | 1.101 | (0.933, 1.299) |

0.2552 | 429 | 1.154 | (1.018, 1.308) |

0.0255 | 613 | 0.6489 |

| Sexual abuse as an adult |

67 | 1.034 | (0.799, 1.340) |

0.7981 | 546 | 1.144 | (1.028, 1.274) |

0.0141 | 613 | 0.4699 |

How to read this table: thoughts of self-harm was regressed on each symptom measure (anxiety or disturbed sleep) as a bivariate model within each subsample of abuse (physical or sexual, as a child or adult) and then again as a multivariate model including the interaction between each symptom measure and abuse measure. For example, anxiety symptoms are positively associated with thoughts of self-harm among women who were physically abused as a child but the association is statistically non-significant (OR=1.011, p=0.9088). The same association is significant among women who were not physically abused as a child (OR=1.114, p=0.0327). However, in the full model the interaction between anxiety symptoms and physical abuse as a child did not reach statistical significance (p=0.3565).

Discussion

As hypothesized, depressed postpartum women who experienced childhood physical abuse were at significantly increased risk for frequent thoughts of self-harm. Other reports similarly indicated a 3 to 4-fold increased risk for SI (Brown et al., 1999; Enns et al., 2006; Fuller-Thomson et al., 2012; McCauley et al., 1997; McHolm et al., 2003) or suicide attempt (Brodsky et al., 2001; Dube et al., 2001; Joiner et al., 2007) in non-puerperal women with MDD and adverse childhood experiences (Brown et al., 1999; Dube et al., 2001; McCauley et al., 1997; Widom et al., 2007), (Teicher et al., 2006). Unexpectedly, childhood sexual abuse did not have a significant main effect on the frequency of thoughts of self-harm. The finding differed from a preponderance of published evidence which implicate the close ties between suicidality and childhood sexual abuse. For example, report from the Adverse Childhood Experience (ACE) study on more than 17,000 adults indicated significantly increased odds for attempted suicide (OR=2.9, 95% CI 2.9, 4.0) with the experience of childhood sexual abuse (Dube et al., 2001). Our findings may have under-estimated the exposure to childhood sexual abuse because some patients were less forth-coming about their experiences of sexual abuse; this is not uncommon with abuse history data obtained from retrospective reports (Widom & Morris, 1997). Also, we used very specific questions adapted from a larger interview schedule (DDIS) to investigate current and past abuse experiences. By not exploring for abuse history with validated tools such as the Childhood Experiences Questionnaire – Revised (Battle et al., 2004; Zanarini et al., 1989) or the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (Bernstein & Fink, 1998; Bernstein et al., 2003; Tyrka et al., 2009), we may have missed identifying past experiences of childhood sexual abuse. Relying on retrospective recall of past experiences may have limited the accuracy of the reports.

Not exploring for experiences of emotional abuse and other adverse childhood exposures was another limitation. We were constrained by differences in the scope of this investigation compared to the primary study. Because we needed to ensure we fully collected the study data and evaluated current patient safety risk at the study visits, in efforts to reduce patient burden we were unable to collect comprehensive data on other past abuse experiences including emotional abuse. Regardless, by not doing so, we may have missed characterizing other possible risk factors for developing thoughts of self-harm in women with postpartum depression.

Interestingly, the anxiety and sleep risk factors for women without the specified abuse histories did not seem to apply to women who had the specified abuse histories. To estimate risks for having self-harm thoughts associated with anxiety symptoms and sleep disturbance, we stratified the patients into groups with and without exposure to the specific abuse. By including sufficient numbers of patients in the sub-groups without the exposure to abuse (N’s were 429 to 546)(Table 4) we could detect the small but significant effect of increased anxiety symptoms or sleep disturbance on the risk for thoughts of self-harm. In contrast, we did not find an effect of anxiety or sleep symptoms on risk for self-harm thoughts in women with exposure to the specified abuse. Including very small numbers of patients in each sub-group (N’s were 67 to 186)(Table 4) may have contributed to the lack of statistical power and absence of a detectable effect in the women with the exposure to abuse. The lack of a detectable effect also might be from that early life history of abuse “overwhelms” any impact that might have been seen from having anxiety symptoms or problems with sleep disturbance. Nevertheless, the absence of interaction effects suggested that anxiety symptoms or sleep disturbance was not associated with a significant risk for thoughts of self-harm in both women with or without exposure to the specified abuse. To circumvent limitations from small sub-group samples, we would need to include additional patients within each subgroup to gain sufficient statistical power to confirm the negative finding in the women with exposure to abuse.

In the analyses, we discovered that compared to mothers without thoughts of self-harm, mothers who had infrequent thoughts of self-harm had significantly more comorbid disorders and reduced functioning. Consistent with findings from earlier studies, women with childhood adversities are susceptible to physical disease, mental disorders (Gilbert et al., 2009; Shonkoff et al., 2009) and pregnancy-related complications including the birth of newborns with low birth weight (Seng et al., 2011). The increased susceptibility to comorbid medical disorders and complications in pregnancy could signify the enduring effects of abuse on the stress response system (Anda et al., 2006; Hyman, 2009). Signs of excessive autonomic stress responses (Heim et al., 2000; Heim et al., 2008), hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis hyper-reactivity (Heim et al., 2001), reduced hippocampal glucocorticoid receptor expression (McGowan et al., 2009), and enhanced cellular immune responsivity (Altemus et al., 2003) provide ample evidence of the abnormal regulation of stress in women with trauma experiences (Anda et al., 2006). Exposure to maternal depression and stress dysregulation can imprint lasting effects on the offspring. Adverse offspring effects include altered development of the HPA axis and limbic systems (Kinsella & Monk, 2009), (Van den Bergh et al., 2005), changes in newborn glucocorticoid receptor activity (Oberlander et al., 2008), and increased stress cortisol levels at 3-months (Oberlander et al., 2008).

In women with PPD, abnormal reward processing may play an etiologic role in SI. New mothers with untreated depression reported reduced levels of gratification, reward and satisfaction in the maternal role (Logsdon et al., 2011). Using a monetary reward paradigm, investigators detected a normal peak in activation but rapid attenuation in the ventral striatum of untreated mothers with PPD versus euthymic controls (Moses-Kolko et al., 2011). Changes in ventral striatal activity and the brain responses to reward (Russo & Nestler, 2013) offer an explanation for the symptoms of anhedonia and reduced reward perception from having PPD (Moses-Kolko et al., 2011). Studies of depressed (non-puerperal) women with experiences of childhood abuse, similarly suggested the increased risk for suicide attempts (Brodsky et al., 2001; Oquendo et al., 2005) and completed suicide (Jokinen et al., 2010) may underscore added problems with aggression, impulsivity and hostility (Brodsky et al., 2001; Jokinen et al., 2010; Oquendo et al., 2005) which could arise from altered reward processing and difficulty in the anticipation of reward (Dillon et al., 2009). In depressed (albeit, older) adults, the positive association between impulsive suicide attempts and a preference for immediate rewards (Dombrovski et al., 2011) representing a ‘myopic view of the future’ (Bechara et al., 2000) again suggests an impairment in the decision-making process. Altogether, growing evidence suggests that during major depressive episodes, problems in making decisions could result in increased suicide risk in depression sub-groups including women with PPD.

New mothers are highly susceptible to sleep disturbance. In the study, the frequency of having thoughts of self-harm ‘sometimes’ or ‘quite often’ was significantly increased in postpartum depressed women with current sleep disturbance. Similarly, other findings suggested a 2-fold increased likelihood for SI or suicide attempt in adults with disturbed sleep (Pigeon et al., 2012). Sleep disturbances, including insomnia and sleep deprivation, can produce labile mood (Zohar et al., 2005) which may correspond with neural responses that suggest abnormal reward processing and autonomic hyperarousal (Franzen & Buysse, 2008), limbic over-activity (Gujar et al., 2011) and loss of medial prefrontal cortex connectivity (Yoo et al., 2007). Having sleep disturbance could worsen the altered reward processes (van der Helm & Walker, 2009) in mothers with depression and SI. Additional study is vital to uncover novel therapeutics to reduce postpartum suicide risk, sleep disturbance and other disabling symptoms of PPD.

Having increased symptoms of anxiety was associated with frequent self-harm thoughts in depressed mothers without specified abuse. Comorbid anxiety disorders are common in new mothers with PPD. As many as 66% of mothers with postpartum unipolar depressive disorders had concurrent anxiety disorders in the parent study (Wisner et al., 2013). Others reported that non-puerperal patients with anxiety disorders including panic disorder or PTSD had twice the risk for suicide attempt (Nepon et al., 2010). Furthermore, depressed patients with extreme anxiety or agitation were at significantly increased risk for suicide within one year (Busch et al., 2003; Fawcett et al., 1990). Given the evidence of a significant association between suicide risk and increased anxiety symptoms in women with PPD, concurrent or residual anxiety symptoms must be assessed and targeted for treatment. The resolution or improvement of depression is not sufficient for full response; treatment to remission of MDD is imperative to ensure that mothers return to full functioning and avoid relapse. Integrating treatments for residual postpartum symptoms of anxiety or disturbed sleep with treatments for PPD (Wisner et al., 2012) including serotonin reuptake inhibitors (Wisner et al., 2006), serotonin-noradrenergic reuptake inhibitors (Cohen et al., 2001), moderately dosed sleep agents (Yonkers et al., 2004), cognitive behavioral therapy (Appleby et al., 1997) or interpersonal therapy (O’Hara et al., 2000) can enhance the response and recovery from postpartum major depression.

In the study, patients with bipolar disorders or psychotic disorders (who were ineligible from the main study) were excluded because they did not provide the full set of clinical measures data that were required for the analyses. There is sufficient evidence that bipolar and psychotic disorders have important biological differences from unipolar depression (de Almeida & Phillips, 2013). To investigate a less heterogeneous group of patients with postpartum disorders, we included only new mothers with unipolar major postpartum depression. However, given the study findings, complexity of postpartum disorders, and the high rates of comorbid anxiety disorders (Wisner et al., 2013) and problems with circadian disruption (Okun et al., 2011) in patients with perinatal mood disorders, future research on the impact of sleep disturbance and anxiety symptoms on suicidality in new mothers with bipolar disorders and psychotic disorders is strongly indicated.

The onset of depression before pregnancy or after delivery was associated significantly with having thoughts of self-harm. Large puerperal shifts in neurosteroid concentrations may have increased the vulnerability for postpartum-onset MDD in mothers with genetic risk(Bloch et al., 2000). However, a link between withdrawal of gonadal steroid hormones and risk for suicidal symptoms has not been elucidated. In contrast, women with pre-pregnancy-onset MDD likely had symptoms of chronic or long-term depression. With chronic depression, patients frequently reported increased hopelessness (Angst et al., 2009; Wiersma et al., 2011). High levels of hopelessness may confer an increased risk for suicide in severely depressed patients (Beck et al., 1985; Fawcett et al., 1990). This knowledge underscores the critical need for depression screening, suicide risk assessment (Joiner et al., 2007; Oquendo et al., 1997), and access to mental health treatment once women begin to receive obstetrical care. Mothers known to have MDD or puerperal recurrences must be flagged for clinical safety monitoring and preventive treatment at the time of delivery (before symptoms recur)(Sit et al., 2006; Wisner et al., 2004).

Because depressed mothers can present with frequent thoughts of self-harm and a high level of clinical complexity, conducting a detailed safety assessment that includes an evaluation of childhood abuse history, current symptoms of sleep disturbance and anxiety is a key component in the management of depressed mothers. Assessing safety should include exploration of suicidal or homicidal ideation or attempts, past or recent hospitalizations, recent medication changes, intolerable drug effects, alcohol and substance use, family history of suicide, and evaluation of protective factors (Mann, 2003). Enlisting supports to stay with the patient and remove access to lethal methods is essential (Mann, 2003). Although validated tools to assess suicidality (Scale for Suicidal Ideation (Beck et al., 1979) or the Columbia C-CASA (Posner et al., 2007) are available, their utility for perinatal women needs further evaluation. For treatment-resistant disorders, medication options which can reduce suicidal symptoms include lithium (Goodwin et al., 2003; Tondo et al., 2001), clozapine (Meltzer & Okayli, 1995; Potkin et al., 2003) and possibly, ketamine (DiazGranados et al., 2010). Evidence-based psychotherapies for suicidal behaviors include dialectical behavioral therapy (Linehan et al., 2006) and add-on family therapy(Miller et al., 2005). Additional investigations to examine the phenomenology and neural markers of reward processing in women with postpartum affective disorders (Jutkiewicz & Roques, 2012; Scott et al., 2008) may inform the development of novel drugs and psychotherapy tools to retrain reward responses, relieve suicidal symptoms and restore normal affective states in postpartum women.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Funding Support. This study was supported by grant R01 MH 071825 for Identification and Therapy of Postpartum Depression (Dr Wisner, principal investigator). Dr. Sit was supported by a K23 Career Development Award, grant K23 MH082114 on Light Therapy for Bipolar Disorder (PI: D. Sit; 2009–2014) and the 2013 NARSAD Young Investigator Grant on Neural and Visual Responses to Light in Bipolar Disorder: A Novel Putative Biomarker.

Disclosures. Dr. Sit received a donation of study light boxes from Uplift Technologies (2009) and compensation for providing consultation on Lauren Alloy’s R01 grant (2014). Dr Wisner participated in an advisory board for Eli Lilly Company and received donated estradiol and placebo transdermal patches from Novartis for a National Institute of Mental Health–funded randomized trial, activities that do not involve the work described in this article. Dr Wisniewski has received compensation for consultation to Bristol-Myers Squibb Company (2007–2008), Organon (2007), Case Western Reserve University (2007), Singapore Clinical Research Institute (2009), Dey Pharmaceuticals (2010), and Venebio (2010) and received payment for his board membership for Cyberonic, Inc (2005–2009).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

We presented our preliminary analyses at the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology 52nd Annual Meeting, Hollywood, FL, December 8–12, 2013; Hot Topics Oral Session on Sunday, December 08, 2013 - Presentation Title: Suicidal Ideation in Depressed New Mothers: Relationship with Childhood Trauma and Sleep Disturbance, and at the Society of Biological Psychiatry 69th Annual Scientific Convention, New York City, May 8–10, 2014; Poster Title: Past Childhood Trauma, Sleep Disturbance and Increased Anxiety Symptoms: Potential Risk factors for Suicidal Ideation in Depressed New Mothers.

References

- Altemus M, Cloitre M, Dhabhar FS. Enhanced cellular immune response in women with PTSD related to childhood abuse. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2003;160:1705–1707. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.9.1705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anda RF, Felitti VJ, Bremner J, Walker JD, Whitfield C, Perry BD, Dube SR, Giles WH. The enduring effects of abuse and related adverse experiences in childhood: A convergence of evidence from neurobiology and epidemiology. European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience. 2006;256:174–186. doi: 10.1007/s00406-005-0624-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angst J, Gamma A, Rossler W, Ajdacic V, Klein DN. Long-term depression versus episodic major depression: Results from the prospective Zurich study of a community sample. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2009;115:112–121. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2008.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Appleby L, Warner R, Whitton A, Faragher B. A controlled study of fluoxetine and cognitive-behavioral counselling in the treatment of postnatal depression. BMJ. 1997;314:932–936. doi: 10.1136/bmj.314.7085.932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Battle CL, Shea MT, Johnson DM, Yen S, Zlotnick C, Zanarini MC, Sanislow CA, Skodol AE, Gunderson JG, Grilo CM, McGlashan TH, Morey LC. Childhood maltreatment associated with adult personality disorders: findings from the Collaborative Longitudinal Personality Disorders Study. Journal of Personality Disorders. 2004;18:193–211. doi: 10.1521/pedi.18.2.193.32777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bechara A, Tranel D, Damasio H. Characterization of the decision-making deficit of patients with ventromedial prefrontal cortex lesions. Brain. 2000;123:2189–2202. doi: 10.1093/brain/123.11.2189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Kovacs M, Weissman A. Assessment of suicidal intention: The Scale for Suicide Ideation. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1979;47:343–352. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.47.2.343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Steer RA, Kovacs M, Garrison B. Hopelessness and eventual suicide: a 10-year prospective study of patients hospitalized with suicidal ideation. American Journal of Psychi atry. 1985;142:559–563. doi: 10.1176/ajp.142.5.559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernert RA, Joiner TE, Jr, Cukrowicz KC, Schmidt NB, Krakow B. Suicidality and sleep disturbances. Sleep: Journal of Sleep and Sleep Disorders Research. 2005;28:1135–1141. doi: 10.1093/sleep/28.9.1135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein DP, Fink L. Childhood Trauma Questionnaire. A retrospective self-report. Manual. San Antonio: The Psychological Corporation, Harcourt Brace and Company. 1998 [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein DP, Stein JA, Newcomb MD, Walker E, Poggee D, Ahluvaliae T, Stokese J, Handelsman L, Medrano M, Desmond D, Zule W. Development and validation of a brief screening version of the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire. Child Abuse and Neglect. 2003;27:169–190. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(02)00541-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloch M, Schmidt PJ, Danaceau M, Murphy J, Nieman L, Rubinow DR. Effects of gonadal steroids in women with a history of postpartum depression. American Journal of Psychi atry. 2000;157:924–930. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.6.924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brent DA, Perper JA, Goldstein CE, Kolko DJ, Allan MJ, Allman CJ, Zelenak JP. Risk factors for adolescent suicide: A comparison of adolescent suicide victims with suicidal inpatients. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1988;45:581–588. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1988.01800300079011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brodsky BS, Oquendo MA, Ellis SP, Haas GL, Malone KM, Mann JJ. The relationship of childhood abuse to impulsivity and suicidal behavior in adults with major depression. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2001;158:1871–1877. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.11.1871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown J, Cohen P, Johnson JG, Smailes EM. Childhood abuse and neglect: specificity of effects on adolescent and young adult depression and suicidality. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 1999;38:1490–1496. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199912000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busch KA, Fawcett J, Jacobs DG. Clinical correlates of inpatient suicide. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2003;64:14–19. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v64n0105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavanagh J, Carson A, Sharpe M, Lawrie S. Psychological autopsy studies of suicide: A systematic review. Psychological Medicine. 2003;33:395–405. doi: 10.1017/s0033291702006943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark DB, Lynch KG, Donovan JE, Block GD. Health problems in adolescents with alcohol use disorders: self-report, liver injury, and physical examination findings and correlates. Alcoholism: Clinical & Experimental Research. 2001;25:1350–1359. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen LS, Viguera AC, Bouffard SM, Nonacs RM, Morabito C, Collins MH, Ablon JS. Venlafaxine in the treatment of postpartum depression. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2001;62:592–596. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v62n0803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comtois KA, Schiff MA, Grossman DC. Psychiatric risk factors associated with postpartum suicide attempt in Washington State, 1992–2001. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2008;199:120.e1–120.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2008.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornelius JR, Salloum IM, Mezzich J, Cornelius MD, Fabrega H, Ehler JG, Ulrich RF, Thase ME, Mann J. Disproportionate suicidality in patients with comorbid major depression and alcoholism. The American Journal of Psychiatry. 1995;152:358–364. doi: 10.1176/ajp.152.3.358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coryell W, Young EA. Clinical Predictors of Suicide in Primary Major Depressive Disorder. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2005;66:412–417. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v66n0401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox JL, Holden JM, Sagovsky R. Detection of postnatal depression. Development of the 10-item Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. British Journal of Psychiatry. 1987;150:782–6. doi: 10.1192/bjp.150.6.782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Almeida JRC, Phillips ML. Distinguishing between unipolar depression and bipolar depression: current and future clinical and neuroimaging perspectives. Biological Psychiatry. 2013;73:111–118. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2012.06.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiazGranados N, Ibrahim LA, Brutsche NE, Ameli R, Henter ID, Luckenbaugh DA, Machado-Vieira R, Zarate CA., Jr Rapid resolution of suicidal ideation after a single infusion of an N-methyl-D-aspartate antagonist in patients with treatment-resistant major depressive disorder. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2010;71:1605–1611. doi: 10.4088/JCP.09m05327blu. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dillon DG, Holmes AJ, Birk JL, Brooks N, Lyons-Ruth K, Pizzagalli DA. Childhood adversity is associated with left basal ganglia dysfunction during reward anticipation in adulthood. Biological Psychiatry. 2009;66:206–213. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.02.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dombrovski AY, Szanto K, Siegle GJ, Wallace ML, Forman SD, Sahakian B, Reynolds CF, III, Clark L. Lethal forethought: delayed reward discounting differentiates high- and low-lethality suicide attempts in old age. Biological Psychiatry. 2011;70:138–144. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.12.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dube SR, Anda RF, Felitti VJ, Chapman DP, Williamson DF, Giles WH. Childhood abuse, household dysfunction and the risk of attempted suicide throughout the life span. JAMA. 2001;286:3089–3096. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.24.3089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enns MW, Cox BJ, Afifi TO, De Graaf R, Ten Have M, Sareen J. Childhood adversities and risk for suicidal ideation and attempts: a longitudinal population-based study. Psychological Medicine. 2006;36:1769–1778. doi: 10.1017/S0033291706008646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fawcett J, Scheftner WA, Fogg L, Clark DC, Young MA, Hedeker D, Gibbons R. Time-related predictors of suicide in major affective disorder. American Journal of Psychi atry. 1990;147:1189–1194. doi: 10.1176/ajp.147.9.1189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW. In: Structured clinical interview for DSM-IV Axis I disorders - patient edition. Washington DC, editor. American Psychiatric Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Franzen PL, Buysse DJ. Sleep disturbances and depression: risk relationships for subsequent depression and therapeutic implications. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience. 2008;10:473–481. doi: 10.31887/DCNS.2008.10.4/plfranzen. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuller-Thomson E, Baker TM, Brennenstuhl S. Evidence supporting an independent association between childhood physical abuse and lifetime suicidal ideation. Suicide & Life-Threatening Behavior. 2012;42:279–291. doi: 10.1111/j.1943-278X.2012.00089.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson J, McKenzie-McHarg K, Shakespeare J, Price J, Gray R. A systematic review of studies validating the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale in antepartum and postpartum women. Acta psychiatrica Scandinavica. 2009;119:350–364. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2009.01363.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert R, Widom CS, Browne K, Fergusson D, Webb E, Janson S. Burden and consequences of child maltreatment in high-income countries. Lancet. 2009;373:68–81. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61706-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin FK, Fireman B, Simon GE, Hunkeler EM, Lee J, Revicki D. Suicide risk in bipolar disorder during treatment with lithium and divalproex. JAMA: Journal of the American Medical Association. 2003;290:1467–1473. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.11.1467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gujar N, Yoo S-S, Hu P, Walker MP. Sleep deprivation amplifies reactivity of brain reward networks, biasing the appraisal of positive emotional experiences. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2011;31:4466–4474. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3220-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton M. A rating scale for depression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1960;23:56–62. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.23.1.56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanusa BH, Scholle SH, Haskett RF, Spadaro K, Wisner KL. Screening for depression in the postpartum period: A comparison of three instruments. Journal of Women’s Health. 2008;17:585–596. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2006.0248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawton K, van Heeringen K. Suicide. The Lancet. 2009;373:1372–1381. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60372-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heim C, Newport D, Bonsall R, Miller AH, Nemeroff CB. Altered pituitary-adrenal axis responses to provocative challenge tests in adult survivors of childhood abuse. The American Journal of Psychiatry. 2001;158:575–581. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.4.575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heim C, Newport D, Heit S, Graham YP, Wilcox M, Bonsall R, Miller AH, Nemeroff CB. Pituitary-adrenal and autonomic responses to stress in women after sexual and physical abuse in childhood. JAMA: Journal of the American Medical Association. 2000;284:592–597. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.5.592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heim C, Newport D, Mletzko T, Miller AH, Nemeroff CB. The link between childhood trauma and depression: Insights from HPA axis studies in humans. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2008;33:693–710. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2008.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howard LM, Flach C, Mehay A, Sharp D, Tylee A. The prevalence of suicidal ideation identified by the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale in postpartum women in primary care: findings from the RESPOND trial. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth. 2011;11:1471–2393. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-11-57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyman SE. How adversity gets under the skin. Nature Neuroscience. 2009;12:241–243. doi: 10.1038/nn0309-241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joiner TE, Jr, Sachs-Ericsson NJ, Wingate LR, Brown JS, Anestis MD, Selby EA. Childhood physical and sexual abuse and lifetime number of suicide attempts: A persistent and theoretically important relationship. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2007;45:539–547. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2006.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jokinen J, Forslund K, Ahnemark E, Gustavsson J, Nordstrom P, Asberg M. Karolinska Interpersonal Violence Scale predicts suicide in suicide attempters. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2010;71:1025–1032. doi: 10.4088/JCP.09m05944blu. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jutkiewicz EM, Roques BP. Endogenous opioids as physiological antidepressants: Complementary role of delta receptors and dopamine. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2012;37:303–304. doi: 10.1038/npp.2011.244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinsella MT, Monk C. Impact of maternal stress, depression and anxiety on fetal neurobehavioral development. Clinical Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2009;52:425–440. doi: 10.1097/GRF.0b013e3181b52df1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis G, Cantwell R, Clutton-Brock T, Cooper G, Dawson A, Drife JD, Garrod D, Harper A, Hulbert D, Lucas S, McClure J, Millward-Sadler H, Neilson J, Nelson-Piercy C, Norman J, O’Herlihy C, Oates M, Shakespeare J, de Swiet M, Williamson C, Beale V, Knight M, Lennox C, Miller A, Parmar D, Rogers J, Springett A. Saving Mothers’ Lives: Reviewing maternal deaths to make motherhood safer: 2006–2008. BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology. 2011;118:1–203. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2010.02847.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linehan MM, Comtois KA, Murray AM, Brown MZ, Gallop RJ, Heard HL, Korslund KE, Tutek DA, Reynolds SK, Lindenboim N. Two-year randomized controlled trial and follow-up of dialectical behavior therapy vs therapy by experts for suicidal behaviors and borderline personality disorder.[Erratum appears in Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007 Dec;64(12):1401] Archives of General Psychiatry. 2006;63:757–766. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.7.757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Logsdon MC, Wisner K, Sit D, Luther JF, Wisniewski SR. Depression treatment and maternal functioning. Depression and Anxiety. 2011;28:1020–1026. doi: 10.1002/da.20892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mann JJ. Neurobiology of suicidal behaviour. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2003;4:819–828. doi: 10.1038/nrn1220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCauley J, Kern DE, Kolodner K, Dill L, Schroeder AF, DeChant HK, Ryden J, Derogatis LR, Bass EB. Clinical characteristics of women with a history of childhood abuse: unhealed wounds. Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA) 1997;277:1362–1368. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGowan PO, Sasaki A, D’Alessio AC, Dymov S, Labonte B, Szyf M, Turecki G, Meaney MJ. Epigenetic regulation of the glucocorticoid receptor in human brain associates with childhood abuse. Nat Neurosci. 2009;12:342–348. doi: 10.1038/nn.2270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McHolm AE, MacMillan HL, Jamieson E. “The relationship between childhood physical abuse and sucidality among depressed women: Results from a community sample”: Reply. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2003;161:763–764. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.5.933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meltzer HY, Okayli G. Reduction of suicidality during clozapine treatment of neuroleptic-resistant schizophrenia: Impact on risk-benefit assessment. The American Journal of Psychiatry. 1995;152:183–190. doi: 10.1176/ajp.152.2.183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller IW, Keitner GI, Ryan CE, Solomon DA, Cardemil EV, Beevers CG. Treatment Matching in the Posthospital Care of Depressed Patients. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2005;162:2131–2138. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.11.2131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moritz S, Meier B, Hand I, Schick M, Jahn H. Dimensional structure of the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale in patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder. Psychiatry Research. 2004;125:171–180. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2003.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moses-Kolko E, Fraser D, Wisner KL, James JA, Saul AT, Riez JA, Phillips ML. Rapid habituation of ventral striatal response to reward receipt in postpartum depression. Biological Psychiatry. 2011;70:395–399. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2011.02.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nepon J, Belik S-L, Bolton J, Sareen J. The relationship between anxiety disorders and suicide attempts: Findings from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Depression and Anxiety. 2010;27:791–798. doi: 10.1002/da.20674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Hara MW, Stuart S, Gorman LL, Wenzel A. Efficacy of interpersonal psychotherapy for postpartum depression. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2000;57:1039–1045. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.57.11.1039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oates M. Perinatal psychiatric disorders: a leading cause of maternal morbidity and mortality. British Medical Bulletin. 2003;67:219–29. doi: 10.1093/bmb/ldg011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oberlander TF, Weinberg J, Papsdorf M, Grunau R, Misri S, Devlin AM. Prenatal exposure to maternal depression, neonatal methylation of human glucocorticoid receptor gene (NR3C1) and infant cortisol stress responses. Epigenetics: Official Journal of the DNA Methylation Society. 2008;3:97–106. doi: 10.4161/epi.3.2.6034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okun ML, Luther J, Prather AA, Perel JM, Wisniewski S, Wisner KL. Changes in sleep quality, but not hormones predict time to postpartum depression recurrence. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2011;130:378–384. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2010.07.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oquendo M, Brent DA, Birmaher B, Greenhill L, Kolko D, Stanley B, Zelazny J, Burke AK, Firinciogullari S, Ellis SP, Mann J. Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Comorbid With Major Depression: Factors Mediating the Association With Suicidal Behavior. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2005;162:560–566. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.3.560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oquendo MA, Malone KM, Mann JJ. Suicide risk factors and prevention in refractory major depression. Depression and Anxiety. 1997;5:202–211. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paris R, Bolton RE, Weinberg MK. Postpartum depression, suicidality, and mother-infant interactions. Arch Womens Mental Health. 2009;12:309–321. doi: 10.1007/s00737-009-0105-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pigeon WR, Pinquart M, Conner K. Meta-analysis of sleep disturbance and suicidal thoughts and behaviors. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2012;73:e1160–e1167. doi: 10.4088/JCP.11r07586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pope CJ, Xie B, Sharma V, Campbell M. A prospective study of thoughts of self-harm and suicidal ideation during the postpartum period in women with mood disorders. Archives of Women’s Mental Health. 2013;16:483–488. doi: 10.1007/s00737-013-0370-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Posner K, Oquendo MA, Gould M, Stanley B, Davies M. Columbia Classification Algorithm of Suicide Assessment (C-CASA): Classification of suicidal events in the FDA’s pediatric suicidal risk analysis of antidepressants. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2007;164:1035–1043. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.164.7.1035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potkin SG, Alphs L, Hsu C, Krishnan K, Anand R, Young FK, Meltzer H, Green A. Predicting Suicidal Risk in Schizophrenic and Schizoaffective Patients in a Prospective Two-Year Trial. Biological Psychiatry. 2003;54:444–452. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(03)00178-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rihmer Z, Rutz W, Pihlgren H. Depression and suicide on Gotland an intensive study of all suicides before and after a depression-training programme for general practitioners. Journal of Affective Disorders. 1995;35:147–152. doi: 10.1016/0165-0327(95)00055-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross CA, Heber S, Norton GR, Anderson D, Anderson G, Barchet P. The Dissociative Disorders Interview Schedule: A Structured Interview. Dissociation. 1989;3:179–189. [Google Scholar]

- Roy A. Family history of suicide. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1983;40:971–974. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1983.01790080053007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russo SJ, Nestler E. The brain reward circuitry in mood disorders. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2013;14:609–625. doi: 10.1038/nrn3381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sareen J, Cox BJ, Afifi TO, de Graaf R, Asmundson GJ, ten Have M, Stein MB. Anxiety Disorders and Risk for Suicidal Ideation and Suicide Attempts: A Population-Based Longitudinal Study of Adults. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2005;62:1249–1257. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.11.1249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott DJ, Stohler CS, Egnatu CM, Wang H, Koeppe RA, Zubieta J-K. Placebo and nocebo effects are defined by opposite opioid and dopaminergic responses. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2008;65:220–231. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2007.34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seng JS, Low LK, Sperlich M, Ronis DL, Liberzon I. Post-traumatic stress disorder, child abuse history, birthweight and gestational age: a prospective cohort study. BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology. 2011;118:1329–1339. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2011.03071.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shonkoff JP, Boyce W, McEwen BS. Neuroscience, molecular biology, and the childhood roots of health disparities building a new framework for health promotion and disease prevention. JAMA: Journal of the American Medical Association. 2009;301:2252–2259. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sit D, Rothschild AJ, Wisner KL. A Review of Postpartum Psychosis. Journal of Women’s Health. 2006;15:352–368. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2006.15.352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teicher MH, Samson JA, Polcari A, McGreenery CE. Sticks, Stones, and Hurtful Words: Relative Effects of Various Forms of Childhood Maltreatment. The American Journal of Psychiatry. 2006;163:993–1000. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2006.163.6.993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tondo L, Hennen J, Baldessarini R. Lower suicide risk with long-term lithium treatment in major affective illness: A meta-analysis. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 2001;104:163–172. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0447.2001.00464.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyrka AR, Price LH, Gelernter J, Schepker C, Anderson GM, Carpenter LL. Interaction of Childhood Maltreatment with the Corticotropin-Releasing Hormone Receptor Gene: Effects on HPA Axis Reactivity. Biological Psychiatry. 2009;66:681–685. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.05.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van den Bergh BR, Mulder EJ, Mennes M, Glover V. Antenatal maternal anxiety and stress and the neurobehavioural development of the fetus and child: Links and possible mechanisms. A review. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews. 2005;29:237–258. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2004.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Helm E, Walker MP. Overnight therapy? The role of sleep in emotional brain processing. Psychological Bulletin. 2009;135:731–748. doi: 10.1037/a0016570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vesga-López O, Blanco C, Keyes K, Olfson M, Grant BF, Hasin DS. Psychiatric disorders in pregnant and postpartum women in the united states. Archives of General Psychi atry. 2008;65:805–815. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.65.7.805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Widom CS, DuMont K, Czaja SJ. A prospective investigation of major depressive disorder and comorbidity in abused and neglected children grown up. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2007;64:49–56. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.1.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Widom CS, Morris S. Accuracy of adult recollections of childhood victimization, Part 2: Childhood sexual abuse. Psychological Assessment. 1997;9:34–46. [Google Scholar]

- Wiersma JE, van Oppen P, van Schaik DJ, van der Does A, Beekman AT, Penninx BW. Psychological characteristics of chronic depression: A longitudinal cohort study. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2011;72:288–294. doi: 10.4088/JCP.09m05735blu. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams JBW, Terman M. Structured Interview Guide for the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale with Atypical Depression Supplement (SIGH-ADS) New York: New York State Psychiatric Institute; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Wisner KL, Hanusa BH, Perel JM, Peindl KS, Piontek CM, Sit DK, Findling RL, Moses-Kolko EL. Postpartum Depression: A Randomized Trial of Sertraline Versus Nortriptyline. Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2006;26:353–360. doi: 10.1097/01.jcp.0000227706.56870.dd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wisner KL, Perel JM, Peindl KS, Hanusa BH, Piontek CM, Findling RL. Prevention of postpartum depression: A pilot randomized clinical trial. The American Journal of Psychiatry. 2004;161:1290–1292. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.7.1290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wisner KL, Sit D, McShea MC, et al. Onset timing, thoughts of self-harm, and diagnoses in postpartum women with screen-positive depression findings. JAMA Psychiatry. 2013;70:490–498. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wisner KL, Sit DK, Altemus M, Bogen DL, Famy CS, Pearlstein TB, Misra D, Reynolds SK, Perel JM. Mental Health and Behavioral Disorders in Pregnancy. In: Gabbe SG NJ, Simpson JL, editors. Obstetrics: Normal and problem pregnancies. Philadelphia: Elsevier Inc; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Yonkers K, Wisner K, Stowe Z, Leibenluft E, Cohen L, Miller L, R M, A V, T S, Altshuler L. Management of bipolar disorders during pregnancy and the postpartum period. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2004;161:608–20. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.4.608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoo S-S, Gujar N, Hu P, Jolesz FA, Walker MP. The human emotional brain without sleep--a prefrontal amygdala disconnect. Current Biology. 2007;17:R877–8. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2007.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zanarini MC, Gunderson JG, Marino MF, Schwartz EO, Frankenburg FR. Childhood experiences of borderline patients. Comprehensive Psychiatry. 1989;30:18–25. doi: 10.1016/0010-440x(89)90114-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zohar D, Tzischinsky O, Epstein R, Lavie P. The Effects of Sleep Loss on Medical Residents’ Emotional Reactions to Work Events: a Cognitive-Energy Model. Sleep: Journal of Sleep and Sleep Disorders Research. 2005;28:47–54. doi: 10.1093/sleep/28.1.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]