Abstract

Background

Global association and experimental studies suggest that alcohol use may increase sexual behavior that poses risk for exposure to sexually-transmitted infections (STI) among heterosexual men and women. However, results from longitudinal and daily recall studies exploring the co-occurrence of alcohol use with various sexual risk outcomes in more naturalistic contexts have been mixed, and the bulk of this research has focused on college students.

Methods

The current study enrolled heavy-drinking emergency department (ED) patients and used a cross-sectional, 30-day Timeline Followback (TLFB) method to examine the daily co-occurrence between alcohol use and three sexual behavior outcomes: Any sex, unprotected intercourse (UI), and UI with casual partners (vs. protected intercourse [PI] with casual partners, or UI/PI with steady partners).

Results

Results indicated that increasing levels of alcohol use on a given day increased the odds of engaging in any sexual activity and that heavy drinking (but not very heavy drinking) on a given day was associated with an increased odds of engaging in UI with either steady or casual partners. However, day-level alcohol use was not associated with an increased odds of UI with casual partners.

Conclusions

These findings suggest that alcohol may play an important role in increasing risk for HIV/STIs among heterosexuals, and support the continued need to target heavy drinking in sex risk reduction interventions. However, our results also suggest that alcohol may not universally result in unprotected sex with casual partners, a behavior posing perhaps the highest risk for HIV/STI transmission.

Keywords: Alcohol, heavy drinking, sex risk, unprotected sex

1. Introduction

Unsafe sex (i.e., unprotected sex that could lead to sexually transmitted infections [STI] and/or unintended pregnancies) is a significant cause of disease and disability (Glasier et al., 2006). Indeed, 6.2% of all disability-adjusted life years is attributable to unprotected sexual behavior in the United States (Ebrahim et al., 2005), and the annual direct medical costs associated with STIs topped $15.6 billion dollars in 2008 (Owusu-Edusei Jr et al., 2013). The resurgence of previously well-controlled STIs (e.g., syphilis; Mattei et al., 2012) and growing treatment resistance (CDC, 2013) suggest that STI-related burden may grow substantially in the near future, highlighting the importance of research into factors contributing to unsafe sex.

Alcohol use has been implicated as a key factor in the spread of STIs (Cook and Clark, 2005; Schneider et al., 2012), due in part to findings from cross-sectional (Grossman and Markowitz, 2005; Sen, 2002) and experimental findings (Rehm et al., 2012) supporting a relationship between alcohol use and unsafe sex. However, design limitations of these studies prevent conclusive inferences about the alcohol-unsafe sex link. Cross-sectional studies focusing on overall involvement in alcohol use and sexual risk (e.g., “over the past 6 months”) cannot establish the temporal proximity of the two behaviors. Moreover, experimental studies examine unprotected sex intentions using hypothetical scenarios. While there is evidence that intentions to use condoms are a robust predictor of condom use (Albarracin et al., 2001; Reinecke et al., 1996), important differences may exist between intentions rated in laboratory settings and real world behavior.

Situational association studies address these limitations by exploring whether alcohol use co-occurs with unsafe sex on the same occasion in naturalistic contexts. Early meta-analyses of event-level studies found that alcohol appeared to be unrelated to increased unsafe sex (Leigh, 2002; Weinhardt and Carey, 2000), but most of these studies explored their co-occurrence on just a few occasions (e.g., first sex, last sex). Studies utilizing more intensive assessments (e.g., cross-sectional daily recall or longitudinal designs) have the potential to explore whether alcohol and unsafe sex co-occur across many days, drinking occasions, and sex events over a given time period. Several such studies have been conducted since the aforementioned meta-analyses were published, and suggest that alcohol use consistently increases the likelihood of sex, but that the use of protection may depend on partner factors. For example, one daily diary study (Kiene et al., 2009) and two studies using situation and day-level recall assessments (Brown and Vanable, 2007; LaBrie et al., 2005) showed that drinking increased the odds of unprotected sex specifically with casual partners. However, at least one daily recall study found the opposite. Heavy drinking was associated with unprotected sex only with steady partners, and this relationship was significant only among women (Scott-Sheldon et al., 2010b). Moreover, one daily diary study found that alcohol use was not associated with condom use (Morrison et al., 2003). As such, while situational association studies are critical to understanding whether alcohol use increases unsafe sex in the real world, findings from these studies have been mixed. The vast majority of these studies have also focused on adolescents and college students. Although this may be warranted because of elevated STI risk among young adults (CDC, 2012), few studies have explored the alcohol-unsafe sex link in a broader range of adults or among those who drink heavily. Hence, findings from past studies on this link may be difficult to generalize beyond college students and young adults.

This study addresses this gap in the literature by examining the day-level co-occurrence between alcohol use level and sexual behavior in a sample of heavy-drinking emergency department patients who have engaged in some sexual risk behavior in the past 3 months (i.e., unprotected sex with a casual partner or unprotected sex with a steady partner who’s fidelity is questioned or known). We used a cross-sectional daily assessment method (Timeline Followback [TLFB]) to explore the association between alcohol use level and three key sex outcomes on a given day: The occurrence of (1) any sex, (2) unprotected intercourse (UI) with either steady or casual partners (vs. protected intercourse [PI]), and (3) UI with a casual partner (vs. “safer” forms of sex, such as PI with casual partners and/or UI/PI with a steady partner). These three variables allowed us to examine the association of alcohol use with engaging in any sex at all versus sex that is associated with increasing levels of risk. Given our study inclusion criteria, UI with any type of partner conveys some risk. However, because this outcome includes UI with steady partners, the risk for STI transmission may be lower for this outcome, since it may be more likely to involve risk reduction efforts other than condom use (e.g., sexual exclusivity, discussion of sexual history and STI status, use of alternative methods of contraception). UI with casual partners (vs. PI with a casual partner or PI/UI with a steady partner), however, likely conveys the highest risk of the three. Based on past findings (e.g., Brown and Vanable, 2007; Kiene et al., 2009; LaBrie et al., 2005; Morrison et al., 2003), we hypothesized that higher levels of alcohol use, specifically use indicative of intoxication (i.e., consuming 5–11, or 12+ drinks on a given day for men, or 4–9, or 10+ drinks for women) would be uniquely associated with an increased odds of engaging in UI with casual partners versus engaging in “safer” forms of sex.

2. Materials and Methods

This study used baseline data from 371 patients seeking medical treatment in the ED who enrolled in a randomized trial of a brief, combined intervention for alcohol and sex risk. This broader study explored whether a brief, motivational interviewing intervention could reduce heavy drinking and sexual risk behavior compared with brief advice. Inclusion criteria were: (1) Scores > 8 for men and > 6 for women on the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT; Babor et al., 2001) or ≥ 1 episode of binge drinking (5+ drinks for males; 4+ for females) in the past 3 months; and (2) reporting unprotected sex or using alcohol/drugs prior to or during sex during the past 3 months with either a casual partner or a steady partner where infidelity was questioned or known. Patients in a mutually monogamous relationship for > 6 months were excluded.

Nine percent of participants reported being bisexual (87.9% women, 12.1% men), 1.6% were gay, 1.6% were lesbian, and 1.1% reported being “not sure” about their sexual orientation. Since factors affecting sexual decision-making among these participants are likely unique (Beyrer et al., 2012; Earl and Albarracín, 2007), we chose to exclude them from the present analyses. Excluding these participants, one transgender participant, and one HIV+ participant resulted in a final sample of 322.

All procedures were approved by university and hospital Institutional Review Boards. Project staff worked on-site in the EDs to identify eligible patients and explain the study. Screening took place with the permission of medical staff and in-between medical care. A mini mental status exam and breathalyzer reading were administered to ensure patients were able to provide informed consent (i.e., the patient was oriented, able to concentrate, and able to understand and remember the requirements of the study).

After informed consent, participants completed most measures using a laptop computer. TLFB measures were collected in interview format to ensure accuracy. Completion of all study measures took 45–60 minutes.

2.1. Measures

2.1.1. Screening measures

Heavy/problematic alcohol use was assessed using the AUDIT, a 10-item questionnaire (Babor et al., 2001). Scores ≥ 8 for males (Conigrave et al., 1995), and ≥ 6 for females (Reinert & Allen, 2002) were used as inclusion criteria. Sexual risk inclusion criteria were assessed using items on HIV/STI risk from past research (Kalichman et al., 1998; Millstein and Moscicki, 1995), including total number of sex partners, frequency of unprotected sex (vaginal or anal), and frequency of alcohol/drug consumption before or during sex in the past 3 months. Demographic characteristics were collected via online questionnaire.

2.2.2. Study measures

Daily alcohol use, drug use, and sexual behaviors were assessed using Timeline Followback (TLFB; Carey et al., 2001; Sobell et al., 1980). Participants reported the number of standard drinks (12 oz. beer, 5 oz. wine, 1.5 oz. of liquor) consumed, and whether marijuana or “other” drugs were used, for each day of the 30 days prior to baseline. Recall accuracy was enhanced by using a calendar and identifying “important dates” for each participant. The TLFB has demonstrated excellent reliability and validity when assessing alcohol and drug use (Fals-Stewart et al., 2000; Sobell and Sobell, 1980; Sobell et al., 1979; Sobell and Sobell, 1979).

The TLFB also assessed sexual behavior on each day, collecting information about partner type (regular vs. casual) and gender, specific sexual activities performed (vaginal, insertive or receptive anal sex), whether sex took place under the influence of alcohol only, drugs only, or both, and whether a condom was used. TLFBs for sexual behavior have been shown to be reliable and valid (Carey et al., 2001; Napper et al., 2010; Weinhardt et al., 1998; Wray et al., in press). Participants were also asked to indicate whether each sex act occurred with a “regular” partner or “casual” partner. “Regular” partners were defined as someone with whom they were in a “romantic, committed relationship with for at least the past 3 months,” and all other partners were coded as “casual.” Participants could specify having multiple partners on a given day, and binary indicators were coded for each type of sexual behavior (e.g., unprotected vaginal/anal sex with a casual partner) on a given day.

2.2. Analysis Plan

We examined daily associations between static and time-varying variables and the occurrence of three types of sexual behaviors: (1) Any vaginal or anal intercourse (insertive or receptive) vs. no sex, (2) unprotected vaginal or anal intercourse (UI) vs. PI (regardless of partner type), and (3) UI with a casual partner vs. PI with a casual partner or UI/PI with a steady partner. Since this final outcome was only relevant for those reporting sex with a casual partner, we restricted this model to these individuals. A four-level, time-varying term was generated to examine the linear effects of alcohol use on a given day and was adjusted for gender. For men: (0) 0 drinks, (1) 1–4 drinks, (2) 5–11 drinks, and (3) 12+ drinks. For women: (0) 0 drinks, (1) 1–3 drinks, (2) 4–9 drinks, and (3) 10+ drinks. These reference groups were chosen to align with NIAAA’s definitions of “heavy drinking” (5+ for men, 4+ for women), as these levels pose higher risks for alcohol-related problems (NIAAA, 2005). The heaviest drinking category (12+ for men, 10+ for women) was chosen given evidence that, for men who drink heavily on average (i.e., 5–12 drinks), 12+ drinks on a given day confers additional risk for alcohol-related problems beyond drinking at “binge” (5+ drinks) levels (Greenfield et al., 2014). The value of the very heavy drinking category for women (10+) was derived by extending gender differences in lower drinking categories (4+/5+) to the highest category. We also tested potential quadratic associations between alcohol use on a given day and sex outcomes. Both linear and quadratic alcohol use terms were centered prior to analysis. If the alcohol use term was significant, we ran separate models to test pairwise odds ratios for each drinking category compared to no drinking.

Given that TLFB data produces cross-sectional, time-series data, we used generalized estimating equations (GEEs) in Stata 13 (Stata Corp., 2013) to account for correlations between reports within subjects (Zeger and Liang, 1986; Zeger et al., 1988). Given the binary nature of all outcomes, binomial distributions with logit link functions were specified. We used a “build up” strategy for including static and time-varying variables in a final model. Past studies have shown that age (e.g., Brown and Vanable, 2007) and gender (e.g., Scott-Sheldon et al., 2010a) are important covariates, so these were added in initial models testing person-level, static covariates. Additional covariates reflecting the average number of drinks per drinking day and the percentage of drug use days across the 30-day TLFB were also added to distinguish between the effects of overall alcohol and drug use involvement and drinking/drug use on a specific day on outcomes. To statistically control for potential differences across participants who engaged in sex only with steady partners and those who had casual partners during the recall period, a binary indicator representing “steady partners only” was also included. In the second model, time-varying linear and quadratic terms for alcohol use on a given day were tested. Finally, we entered time-varying terms for marijuana and other drug use on a given day to explore whether alcohol terms remained significant above-and-beyond drug use.

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics

See Table 1 for demographics. Although the demographic characteristics of ED patients meeting criteria for “hazardous drinking” varies considerably across studies, fewer participants in our sample were married (likely due to our sexual risk eligibility criterion) but were otherwise similar to past studies conducted in EDs (e.g., Cherpitel, 1995; Neumann et al., 2004). TLFB data were entirely complete, with 0% of days missing. Thus, participants provided 9,660 person-days of data across the 30-day recall period. Sex occurred on a total of 2,982 days (30.9% of days), and participants reported a mean of 9.3 (SD = 8.6) sex days in this window. Of these sex events, 81.6% (2,434) were unprotected. Fifty-six percent of participants reported having sex with only steady partners, and 33.8% reported sex with only casual partners. Among those participants reporting any sex with casual partners in the 30 days, 61.0% (741) of days involved sex with a casual partner. Of all sex days, 96.0% involved vaginal intercourse only, and 3.5% involved vaginal and anal intercourse.

TABLE 1.

Demographic and descriptive characteristics of the analyzed sample (N = 321)

| Characteristics | Mean (SD) or N (%) |

|---|---|

| Age (Range: 18 – 60, M ± SD) | 29.6 (9.5) |

| Gender | |

| Female | 162 (50.3) |

| Male | 160 (49.7) |

| Race | |

| White | 257 (80.1) |

| Black or African American | 43 (13.4) |

| American Indian/Alaska Native | 16 (5.0) |

| Asian | 1 (0.3) |

| Pacific Islander | 1 (0.3) |

| Ethnicity (Hispanic or Latino) | 43 (13.4) |

| Marital Status | |

| Single/Never married | 182 (56.7) |

| In a committed relationship | 61 (19.0) |

| Divorced | 22 (6.9) |

| In a domestic partnership | 19 (5.9) |

| Separated | 17 (5.3) |

| Married | 12 (3.7) |

| Widowed | 6 (1.9) |

| Other | 2 (0.6) |

| Education | |

| Grade school | 4 (1.3) |

| Some high school | 52 (16.2) |

| High school diploma/GED | 121 (37.7) |

| Some college education | 81 (25.2) |

| Technical or business school | 10 (3.1) |

| Two-year college | 21 (6.5) |

| Four-year college | 29 (9.0) |

| Master’s degree | 3 (0.9) |

| Employment status | |

| Unemployed | 127 (39.6) |

| Part-time | 70 (21.8) |

| Full-time | 99 (30.8) |

| Full-time student | 11 (3.4) |

| Part-time student | 8 (2.5) |

| Home maker | 5 (1.6) |

| Retired | 1 (0.3) |

| Income | |

| $0 – $29,999 | 205 (64.3) |

| $30,000 – $59,999 | 77 (24.1) |

| $60,000 – $89,000 | 28 (8.8) |

| $90,000+ | 9 (2.8) |

| % AUDIT Score ≥ 8 | 177 (55.14) |

| Total # of drinking days | 177 (55.14) |

| % Marijuana users | 9.7 (12.7) |

| Average # of marijuana use days | 50 (15.6) |

| % Drug users | 1.1 (4.3) |

| Average # of drug use days |

Participants reported drinking on 2,830 (29.3%) of the days assessed. Participants drank an average of 8.7 (SD = 7.1) out of 30 days (29.1% of days), with a mean of 7.4 (SD = 6.4) drinks per drinking day. They reported an average of 5.8 (SD = 7.1) heavy drinking days. Forty-nine percent of participants reported very heavy drinking on at least one day (for men, 12+ drinks; for women, 10+ drinks), and among these very heavy drinkers, an average of 2.2 (SD = 5.1) such days were reported. Forty-two percent of days on which sexual intercourse occurred were days on which drinking also occurred, 42.3% of days on which UI occurred were drinking days, and 52.2% of days on which UI with a casual partner occurred were drinking days.

3.2. Daily Models of Sexual Behavior

Table 2 shows descriptive statistics and pairwise correlations among person-level variables. Although unprotected sex is subsumed under the “any vaginal or anal sex” variable, the latter reflects a broader number of events. While these variables are expectedly correlated, at least 14% of the variance is independent of the other.

TABLE 2.

Pairwise correlations for individual-level variables

| Variables | M | SD | Range | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Total # of any vaginal or anal sex | 9.32 | 8.63 | 0–30 | |||||||

| 2. Total # UI events | 7.56 | 8.49 | 0–30 | 0.86* | ||||||

| 3. Total # UI w/ casual partner | 2.30 | 5.58 | 0–30 | 0.38* | 0.45* | |||||

| 4. Gender | 162F/160M | 0.07 | 0.09 | 0.07* | ||||||

| 5. Age | 29.59 | 9.47 | 18–60 | 0.01 | 0.01 | −0.03* | −0.05 | |||

| 6. Average drinks/drinking day | 7.38 | 6.42 | 1–22 | 0.09 | 0.13* | 0.10 | 0.01 | −0.01 | ||

| 7. % of other drug use days | 3.64 | 14.14 | 0–100 | −0.03 | −0.02* | 0.05 | −0.04 | 0.08 | 0.06 | |

| 8. Steady partners only | 165Y/157N | 0.14* | 0.16* | −0.45* | −0.03 | 0.10 | −0.08 | −0.08 | ||

Note. p < .05. UI = unprotected intercourse. Sexual behavior variables reflect the total number of days reported involving each across the 30-day assessment period.

3.2.1. Any sexual intercourse

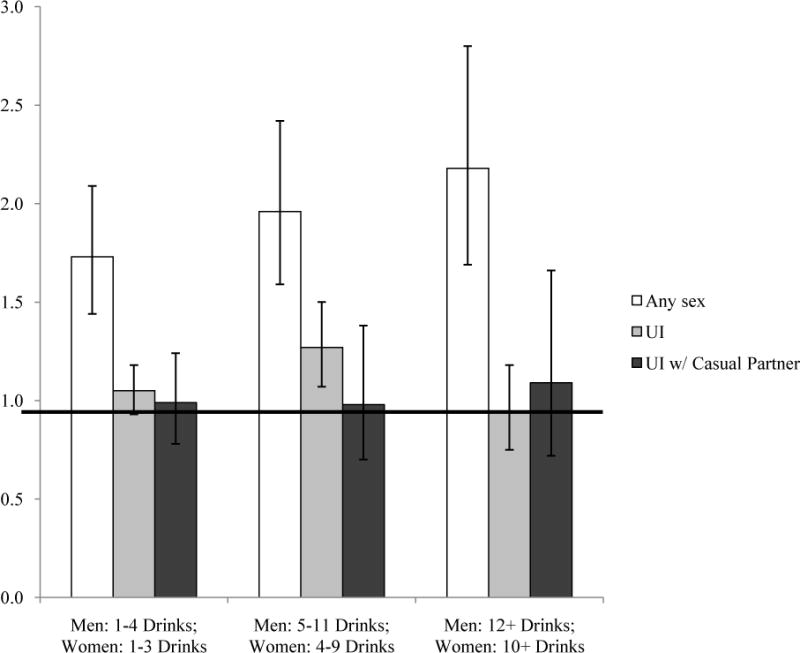

In Model 1 of time-invariant terms, reporting sex with only steady partners during the 30-day period was positively associated with the odds of having any intercourse on a given day, and this association remained significant in later models (Table 3, column 1). In Model 2, level of alcohol use on a given day was positively associated with the odds of engaging in any intercourse, and this relationship appeared to be quadratic. Comparing incrementally increasing alcohol use level categories against the reference group (no drinking) confirmed this effect (see Figure 1), suggesting that the relationship is slightly concave with the greatest increases occurring from no drinking to the lowest drinking category and leveling off as drinking increased. Compared to non-drinking days, the odds of engaging in any intercourse was 0.7 times higher when drinking was at the lowest category (men: 1–4 drinks, women: 1–3 drinks; p < .001), 0.9 times higher when above binge levels (men: 5–11, women: 4–9; p < .001), and 1.1 times higher at very high levels (men: 12+, women: 10+; p < .001). Entering time-varying drug use terms for marijuana and other drug use (Model 3) did not change the effects of alcohol, but day-level marijuana use was also positively associated with the odds of any sex.

TABLE 3.

Generalized Estimating Equations (GEE) for daily reports of engaging in any sexual intercourse (vaginal or anal), unprotected intercourse (UI), and UI with a casual partner

|

Any sexual intercourse (N = 322) |

UI1 (N = 322) |

UI with a casual partner2 (N = 144) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | OR | SE | p | OR | SE | p | OR | SE | p |

| Model 13 | |||||||||

| Gender | 1.21 | 0.18 | .159 | 1.61 | 0.43 | .077 | 1.84 | 0.55 | .042 |

| Age | 1.00 | 0.01 | .765 | 1.02 | 0.02 | .206 | 1.01 | 0.02 | .569 |

| Avg.drinks/drink day4 | 1.02 | 0.01 | .207 | 1.08 | 0.03 | .013 | 1.01 | 0.03 | .687 |

| % drug use days4 | 0.99 | 0.01 | .195 | 1.02 | 0.01 | .255 | 1.02 | 0.01 | .142 |

| Steady partners only | 1.57 | 0.23 | .002 | 2.08 | 0.54 | .005 | – | – | – |

| Model 2 | |||||||||

| Daily alcohol use6 | 1.41 | 0.06 | <.001 | 1.03 | 0.04 | .557 | 1.03 | 0.08 | .667 |

| Daily alc use (quad) | 0.85 | 0.04 | <.001 | 0.92 | 0.03 | .028 | 1.02 | 0.08 | .745 |

| Model 3 | |||||||||

| Daily alcohol use | 1.39 | 0.06 | <.001 | 1.03 | 0.04 | .557 | 1.03 | 0.08 | .697 |

| Daily alc use (quad) | 0.85 | 0.04 | <.001 | 0.92 | 0.03 | .028 | 1.02 | 0.08 | .767 |

| Daily marijuana use | 1.45 | 0.17 | .002 | 1.06 | 0.15 | .658 | 1.20 | 0.28 | .425 |

| Daily other drug use | 1.50 | 0.41 | .138 | 0.97 | 0.14 | .839 | 0.70 | 0.21 | .245 |

Note. OR = Odds ratio, SE = Standard error.

Versus any protected intercourse (vaginal or anal), regardless of partner type.

Versus protected intercourse (vaginal or anal) with a casual partner or unprotected intercourse with a regular partner. Restricted to only participants reporting any casual sex during the 30-day period (N = 157).

Values are final model values.

Averaged over the full 30-day recall period.

Center for Epidemiologic Studies – Depression Scale

Coded each day as 0 = no drinking, 1 = 1–4 drinks for men/1–3 drinks for women, 2 = 5–11 drinks for men/4–9 drinks for women, and 3 = 12+ drinks for men, 10+ drinks for women.

Figure 1.

Odds ratios estimated from GEE models for engaging in any sexual intercourse and unprotected intercourse (UI) with any partner type on a given day by daily alcohol use category (with no alcohol use as the reference category)

3.2.2. Unprotected vaginal or anal intercourse (UI)

In Model 1, both the average number of drinks per drinking day and having only steady partners were positively associated with the odds of having UI regardless of partner type, and these relationships remained after accounting for day-level variables in Models 2 and 3 (Table 3, column 2). In Model 2, the quadratic term for alcohol use level on a given day was positively associated with UI. Plotting the odds ratios of each drinking category against no drinking suggested that this relationship appeared to be an inverted “U,” with odds of engaging in UI increasing in the heavy drinking category (men: 5–11 drinks, women: 4–9 drinks, p = .014), but the odds in the lighter and very heavy drinking categories not differing from no drinking (see Figure 1). This relationship did not change after entering terms for marijuana and other drug use in Model 3 and neither of these terms were significant.

3.2.3. UI with a casual partner

In Model 1, only female gender was positively associated with the odds of having UI with a casual partner among those reporting sex with casual partners (Table 3, column 3). This relationship remained in the final model. Neither linear nor quadratic terms for alcohol use level were significant in Model 2. In addition, none of the day-level drug use variables entered in Model 3 were significant. As such, in the full model, only female gender was significantly related to increases in the odds of UI with a casual partner.

4. Discussion

This study is among the first to examine day-level relationships between alcohol use and sexual risk behaviors among heavy drinking, heterosexual emergency department patients. It is unique in its exploration of these associations in a more diverse sample with heavier drinking patterns than past studies. Using TLFB data, we examined whether alcohol use level on a given day was associated with engagement in sex, the use of protection during sex, and the type of partner (“casual” vs. “steady”) involved in UI. Results partially supported our hypotheses. Alcohol use level appeared to increase the odds of engaging in any vaginal or anal sex on a given day, and drinking heavily, but not very heavily, was associated with an increased odds of engaging in UI with any partner type. However, contrary to expectations, alcohol use on a given day was not associated with an increased odds of engaging in UI specifically with casual partners among those reporting casual sex.

Overall, these results are consistent with past experimental studies suggesting that moderate doses of alcohol (BAC≈0.08) are generally associated with increased desire to have sex (George et al., 2009) and intentions to have unprotected sex (Rehm et al., 2012). However, our findings add nuance to these results, showing that (1) increases in UI when drinking heavily may be driven by less condom use with steady partners, and (2) increased odds of UI may be increased uniquely at heavy, but not moderate or very heavy drinking levels.

The finding that alcohol use level on a given day is associated with increases in UI specifically with steady partners is consistent with one prior daily recall study (Scott-Sheldon, Carey, & Carey, 2010a), but inconsistent with many others showing that alcohol use was associated with increased unprotected sex specifically with casual partners (Brown and Vanable, 2007; Kiene et al., 2009; LaBrie et al., 2005). All of these studies focused on college students, however, so these inconsistent results could suggest important differences across samples. For example, college students may be exposed to different social norms around alcohol use and “hooking up” than older adults (Garcia et al., 2012), leading to more frequent casual sex when drinking.

Although unprotected sex with casual partners may perhaps pose the highest risk for HIV/STI transmission, our finding that drinking heavily could increase odds for UI primarily with steady partners is nevertheless important, and may still be an important risk pathway. In this study, reporting sex with a “steady” partner did not necessarily guarantee that sex occurred exclusively with that partner or that efforts to reduce risk had been employed (e.g., communicating about HIV/STI status, having sex concurrently with other partners) . As such, in this study, any UI may represent an important outcome that conveys risk, despite its occurring with a steady partner.

The finding that the increased risk for UI is specific to heavy levels of drinking on a given day, but not very heavy levels (12+ drinks for men, 10+ drinks for women), is surprising. One possible interpretation is that alcohol’s effects on protective decision-making are unique at this level (5–11 drinks for men, 4–9 for women) compared with lower and higher levels of drinking. That is, while alcohol may universally produce higher intentions for engaging in any sexual activity (Rehm et al., 2012), drinking amounts consistent with the lowest drinking category on a given day may not affect judgment and decision-making enough to impact condom use decisions (e.g., Norris et al., 2009). In contrast, drinking very heavily could produce increasingly sedating effects that lead to comparatively conservative decision-making (Wray et al., June, 2013). However, in our study, both drinking and sexual activity were assessed at the day level, so the specific blood alcohol levels and alcohol effects at the time of sex cannot be determined and these interpretations are speculative. Future research using more refined assessment techniques is needed to evaluate this hypothesis. Nevertheless, our results demonstrate that heavy levels of alcohol use on a given day could increase the odds of UI, highlighting the utility of interventions addressing heavy drinking for reducing high-risk sex.

It is important to note that, in general, these results diverge from research conducted with men who have sex with men (MSM), which shows strong support for alcohol’s role in increasing HIV/STI transmission (Sander et al., 2013; Vosburgh et al., 2012). Specifically, studies suggest that very high levels of alcohol use on a given day are associated with increases in unprotected anal intercourse with serodiscordant partners (Kahler et al., 2014; Vosburgh et al., 2012), supporting the need to explore new ways of addressing heavy drinking among MSM to reduce risk for HIV/STIs.

Unsurprisingly, our findings suggest that reporting sex with only steady partners was positively associated with the odds of both having sex and having unprotected sex on a given day, likely reflecting more frequent sex with steady partners and potential reliance on methods of contraception other than condoms. However, several other findings were surprising. First, marijuana use was associated with higher odds of any sex on that day, but neither the day-level or overall use of other drugs (cocaine, heroin, methamphetamine, etc.) were associated with risk outcomes. These results are inconsistent with some global studies suggesting that the use of particular illicit drugs is associated with increased sexual risk (Bogart et al., 2005; Zule et al., 2007). However, the TLFB used in this study did not differentiate between the different types of other drugs used, and it is likely that specific types of drugs, like cocaine and methamphetamine, are associated with risk, given their potential to increase sexual arousal and stamina (Zule et al., 2007), whereas others (e.g., heroin) impede sexual activity (Ross and Williams, 2001; Semaan et al., 2007). Our results may also be due to the relatively low levels of drug use in this sample (only 3.6% of all days were other drug use days).

Among those who had sex with casual partners, female gender was associated with a 1.84 times higher odds of engaging in UI with a casual partner. Indeed, 60% of all unprotected sex events with casual partners occurred among women. Although high rates of lifetime casual sexual partnerships among heterosexual men has produced the assumption that men are at increased risk for HIV/STI acquisition (and subsequent transmission to female partners; see Higgins et al., 2010; Vitellone, 2000), our results suggest that female heavy drinkers who have casual partners could be important targets for intervention. This finding is important because of the higher biological vulnerability to STI and HIV transmission through heterosexual contact among women (Bolan et al., 1999; Cohen, 1998; Moench et al., 2001; Wasserheit, 1992). It should be noted that these results are not explained by higher levels of transactional sex; several participants (5.4%) reported having 15 or more unprotected sex events with casual partners over the 30 days, and of these, 67% (N = 12) were women, but only 17% of these (N = 2) reported engaging in transactional sex in their lifetimes. As such, our results support the continued need to target women in sex risk reduction interventions.

Several limitations should be noted. First, alcohol use level was assessed across the entire day, so the temporal sequence of drinking and sex cannot be definitively established, nor can participants’ intoxication level at the time sex occurred, limiting causal inferences based on these data. Our assessment also focused on the 30 days prior to a hospital visit, so it provided a limited window into patients’ broader behavioral patterns. Finally, as our sample was comprised of heavy drinking adults who reported at least some sexual risk in the past 3 months and volunteered to participate in a behavioral intervention study, this sample may differ in important ways from other samples of ED patients, limiting generalizability.

In summary, this study explored the daily co-occurrence of alcohol use and sexual risk behavior among heavy drinking emergency department patients using TLFB. Alcohol use on a given day was associated with an increased odds of engaging in any sexual intercourse, and these odds incrementally increased with higher levels of drinking. However, only heavy drinking (but not very heavy drinking) was associated with an increased odds of engaging in UI with either steady or casual partners. Alcohol use on a given day was not associated with having UI with a casual partner, suggesting that the increase in UI observed on heavy drinking days is specific to steady partners. These findings suggest that alcohol may play an important role in increasing risk for HIV/STIs, but that it may not universally result in unprotected sex with casual partners, a behavior posing perhaps the highest risk for HIV/STI transmission.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants R01AA009892, T32AA007459, and L30 AA023336.

References

- Albarracin D, Johnson BT, Fishbein M, Muellerleile PA. Theories of reasoned action and planned behavior as models of condom use: a meta-analysis. Psychol Bull. 2001;127:142. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.127.1.142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babor TF, Higgins-Biddle JC, Saunders JB, Monteiro MG. The alcohol use disorders identification test. Guidelines for use in primary care. 2001;2 [Google Scholar]

- Beyrer C, Baral SD, van Griensven F, Goodreau SM, Chariyalertsak S, Wirtz AL, Brookmeyer R. Global epidemiology of HIV infection in men who have sex with men. The Lancet. 2012;380:367–377. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60821-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogart LM, Kral AH, Scott A, Anderson R, Flynn N, Gilbert ML, Bluthenthal RN. Sexual risk among injection drug users recruited from syringe exchange programs in California. Sex Transm Dis. 2005;32:27–34. doi: 10.1097/01.olq.0000148294.83012.d0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolan G, Ehrhardt AA, Wasserheit JN. Gender perspectives and STDs. In: Holmes K, Sparling P, Stamm W, Piot P, Wasserheit JN, Corey L, Cohen M, editors. Sex Transm Dis. McGraw-Hill; New York: 1999. pp. 117–127. [Google Scholar]

- Brown JL, Vanable PA. Alcohol use, partner type, and risky sexual behavior among college students: Findings from an event-level study. Addict Behav. 2007;32:2940–2952. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carey MP, Carey K, Maisto S, Gordon C, Weinhardt L. Assessing sexual risk behaviour with the Timeline Followback (TLFB) approach: continued development and psychometric evaluation with psychiatric outpatients. International journal of STD & AIDS. 2001;12:365–375. doi: 10.1258/0956462011923309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually transmitted disease surveillance, 2011. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; Atlanta, GA: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Gonorrhea Treatment Guidelines: Revised guidelines to preserve last effective treatment option. National Center for HIV/AIDS, Viral Hepatitis, STD, and TB Prevention; Atlanta, GA: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Cherpitel CJ. Screening for alcohol problems in the emergency department. Ann Emerg Med. 1995;26:158–166. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(95)70146-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen MS. Sexually transmitted diseases enhance HIV transmission: no longer a hypothesis. The Lancet. 1998;351:S5–S7. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(98)90002-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook RL, Clark DB. Is there an association between alcohol consumption and sexually transmitted diseases? A systematic review. Sex Transm Dis. 2005;32:156–164. doi: 10.1097/01.olq.0000151418.03899.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Earl A, Albarracín D. Nature, decay, and spiraling of the effects of fear-inducing arguments and HIV counseling and testing: A meta-analysis of the short-and long-term outcomes of HIV-prevention interventions. Health Psychology. 2007;26:496. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.26.4.496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebrahim S, McKenna M, Marks J. Sexual behaviour: related adverse health burden in the United States. Sex Transm Infect. 2005;81:38–40. doi: 10.1136/sti.2003.008300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fals-Stewart W, O’Farrell TJ, Freitas TT, McFarlin SK, Rutigliano P. The timeline followback reports of psychoactive substance use by drug-abusing patients: Psychometric properties. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2000;68:134–144. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.68.1.134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia JR, Reiber C, Massey SG, Merriwether AM. Sexual hookup culture: A review. Rev Gen Psychol. 2012;16:161. doi: 10.1037/a0027911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George WH, Davis KC, Norris J, Heiman JR, Stoner SA, Schacht RL, Hendershot CS, Kajumulo KF. Indirect effects of acute alcohol intoxication on sexual risk-taking: The roles of subjective and physiological sexual arousal. Arch Sex Behav. 2009;38:498–513. doi: 10.1007/s10508-008-9346-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glasier A, Gülmezoglu AM, Schmid GP, Moreno CG, Van Look PF. Sexual and reproductive health: a matter of life and death. The Lancet. 2006;368:1595–1607. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69478-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenfield TK, Ye Y, Bond J, Kerr WC, Nayak MB, Kaskutas LA, Anton RF, Litten RZ, Kranzler HR. Risks of alcohol use disorders related to drinking patterns in the US general population. Journal of studies on alcohol and drugs. 2014;75:319–327. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2014.75.319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grossman M, Markowitz S. I did what last night?! Adolescent risky sexual behaviors and substance use. Eastern Economic Journal. 2005;31:383–405. [Google Scholar]

- Higgins JA, Hoffman S, Dworkin SL. Rethinking gender, heterosexual men, and women’s vulnerability to HIV/AIDS. Am J Public Health. 2010;100:435. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.159723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahler CW, Wray TB, Pantalone D, Kruis R, Mastroleo NR, Mayer K, Monti PM. Daily relationships between alcohol use and high-risk sexual behavior among HIV-infected men who have sex with men. AIDS Behav. 2014 doi: 10.1007/s10461-014-0896-7. Online first publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalichman SC, Williams EA, Cherry C, Belcher L, Nachimson D. Sexual coercion, domestic violence, and negotiating condom use among low-income African American women. Journal of Women’s Health. 1998;7:371–378. doi: 10.1089/jwh.1998.7.371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiene SM, Barta WD, Tennen H, Armeli S. Alcohol, helping young adults to have unprotected sex with casual partners: findings from a daily diary study of alcohol use and sexual behavior. J Adolesc Health. 2009;44:73–80. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2008.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaBrie J, Earleywine M, Schiffman J, Pedersen E, Marriot C. Effects of alcohol, expectancies, and partner type on condom use in college males: Event-level analyses. J Sex Res. 2005;42:259–266. doi: 10.1080/00224490509552280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leigh BC. Alcohol and condom use: a meta-analysis of event-level studies. Sexually transmitted diseases. 2002;29:476–482. doi: 10.1097/00007435-200208000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattei PL, Beachkofsky TM, Gilson RT, Wisco OJ. Syphilis: A reemerging infection. Am Fam Physician. 2012;86:433–440. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millstein SG, Moscicki AB. Sexually-transmitted disease in female adolescents: Effects of psychosocial factors and high risk behaviors. Journal of Adolescent Health. 1995;17:83–90. doi: 10.1016/1054-139X(95)00065-Z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moench TR, Chipato T, Padian NS. Preventing disease by protecting the cervix: the unexplored promise of internal vaginal barrier devices. AIDS. 2001;15:1595–1602. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200109070-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrison DM, Gillmore MR, Hoppe MJ, Gaylord J, Leigh BC, Rainey D. Adolescent drinking and sex: Findings from a daily diary study. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health. 2003;35:162–168. doi: 10.1363/psrh.35.162.03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Napper LE, Fisher DG, Reynolds GL, Johnson ME. HIV risk behavior self-report reliability at different recall periods. AIDS Behav. 2010;14:152–161. doi: 10.1007/s10461-009-9575-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Helping patients who drink too much: A clinician’s guide. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; Rockville, MD: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Neumann T, Neuner B, Gentilello LM, Weiss-Gerlach E, Mentz H, Rettig JS, Schröder T, Wauer H, Müller C, Schütz M. Gender differences in the performance of a computerized version of the alcohol use disorders identification test in subcritically injured patients who are admitted to the emergency department. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2004;28:1693–1701. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000145696.58084.08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norris J, Stoner SA, Hessler DM, Zawacki T, Davis KC, George WH, Morrison DM, Parkhill MR, Abdallah DA. Influences of sexual sensation seeking, alcohol consumption, and sexual arousal on women’s behavioral intentions related to having unprotected sex. Psychol Addict Behav. 2009;23:14. doi: 10.1037/a0013998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owusu-Edusei K, Jr, Chesson HW, Gift TL, Tao G, Mahajan R, Ocfemia MCB, Kent CK. The estimated direct medical cost of selected sexually transmitted infections in the United States, 2008. Sex Transm Dis. 2013;40:197–201. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e318285c6d2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rehm J, Shield KD, Joharchi N, Shuper PA. Alcohol consumption and the intention to engage in unprotected sex: Systematic review and meta-analysis of experimental studies. Addiction. 2012;107:51–59. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2011.03621.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinecke J, Schmidt P, Ajzen I. Application of the theory of planned behavior to adolescents’ condom use: A panel study1. J Appl Soc Psychol. 1996;26:749–772. [Google Scholar]

- Ross MW, Williams ML. Sexual behavior and illicit drug use. Annu Rev Sex Res. 2001;12:290–310. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sander PM, Cole SR, Stall RD, Jacobson LP, Eron JJ, Napravnik S, Gaynes BN, Johnson-Hill LM, Bolan RK, Ostrow DG. Joint effects of alcohol consumption and high-risk sexual behavior on HIV seroconversion among men who have sex with men. AIDS. 2013;27:815–823. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32835cff4b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider M, Chersich M, Neuman M, Parry C. Alcohol consumption and HIV/AIDS: the neglected interface. Addiction. 2012;107:1369–1371. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2012.03824.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott-Sheldon LA, Carey MP, Carey KB. Alcohol and risky sexual behavior among heavy drinking college students. AIDS Behav. 2010a;14:845–853. doi: 10.1007/s10461-008-9426-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott-Sheldon LAJ, Carey MP, Carey KB. Alcohol and risky sexual behavior among heavy drinking college students. AIDS and Behavior. 2010b;14:845–853. doi: 10.1007/s10461-008-9426-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Semaan S, Don C, Des Jarlais PD, Malow RM. Behavioral interventions for prevention and control of sexually transmitted diseases. Springer; 2007. STDs among illicit drug users in the United States: The need for interventions; pp. 397–430. [Google Scholar]

- Sen B. Does alcohol-use increase the risk of sexual intercourse among young people? Evidence from the NLSY97. Journal of Health Economics. 2002;21:1085–1093. doi: 10.1016/s0167-6296(02)00079-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobell L, Sobell M. Evaluating alcohol and drug abuse treatment effectiveness: Recent advances. Pergamon Press; New York: 1980. Convergent validity: An approach to increasing confidence in treatment outcome conclusions with alcohol and drug abusers; pp. 177–183. [Google Scholar]

- Sobell LC, Maisto SA, Sobell MB, Cooper AM. Reliability of alcohol abusers’ self-reports of drinking behavior. Behav Res Ther. 1979;17:157–160. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(79)90025-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobell LC, Sobell MB. Validity of self-reports in three populations of alcoholics. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1979;46:901–907. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.46.5.901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobell MB, Maisto S, Sobell L, Cooper A, Cooper T, Sanders B. Evaluating alcohol and drug abuse treatment effectiveness: Recent advances. Pergamon Press; New York: 1980. Developing a prototype for evaluating alcohol treatment effectiveness; pp. 129–150. [Google Scholar]

- Vitellone N. Condoms and the Making of “Testosterone Man” A Cultural Analysis of the Male Sex Drive in AIDS Research on Safer Heterosex. Men and Masculinities. 2000;3:152–167. [Google Scholar]

- Vosburgh HW, Mansergh G, Sullivan PS, Purcell DW. A review of the literature on event-level substance use and sexual risk behavior among men who have sex with men. AIDS and Behavior. 2012;16:1394–1410. doi: 10.1007/s10461-011-0131-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wasserheit JN. Epidemiological synergy: interrelationships between human immunodeficiency virus infection and other sexually transmitted diseases. Sex Transm Dis. 1992;19:61–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinhardt LS, Carey MP. Does alcohol lead to sexual risk behavior? Findings from event-level research. Annual review of sex research. 2000;11:125–157. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinhardt LS, Carey MP, Maisto SA, Carey KB, Cohen MM, Wickramasinghe SM. Reliability of the timeline follow-back sexual behavior interview. Ann Behav Med. 1998;20:25–30. doi: 10.1007/BF02893805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wray TB, Braciszewski JM, Zywiak WH, Stout RL. Examining the reliability of alcohol/drug use and HIV-risk behaviors using Timeline Followback in a Pilot Sample. Journal of Substance Use. doi: 10.3109/14659891.2015.1018974. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wray TB, Simons JS, Maisto S. Effects of alcohol consumption on heart rate, subjective drug effects, and sexual behavior 2013 Jun; [Google Scholar]

- Zeger SL, Liang KY. Longitudinal data analysis for discrete and continuous outcomes. Biometrics. 1986:121–130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeger SL, Liang KY, Albert PS. Models for longitudinal data: a generalized estimating equation approach. Biometrics. 1988:1049–1060. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zule WA, Costenbader EC, Meyer WJ, Jr, Wechsberg WM. Methamphetamine use and risky sexual behaviors during heterosexual encounters. Sex Transm Dis. 2007;34:689–694. doi: 10.1097/01.olq.0000260949.35304.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]