Abstract

Formaldehyde (FA) is a human carcinogen with numerous sources of environmental and occupational exposures. This reactive aldehyde is also produced endogenously during metabolism of drugs and other processes. DNA-protein crosslinks (DPC) are considered to be the main genotoxic lesions for FA. Accumulating evidence suggests that DPC repair in high eukaryotes involves proteolysis of crosslinked proteins. Here, we examined a role of the main cellular proteolytic machinery proteasomes in toxic responses of human lung cells to low FA doses. We found that transient inhibition of proteasome activity increased cytotoxicity and diminished clonogenic viability of FA-treated cells. Proteasome inactivation exacerbated suppressive effects of FA on DNA replication and increased the levels of the genotoxic stress marker γ-H2AX in normal human cells. A transient loss of proteasome activity in FA-exposed cells also caused delayed perturbations of cell cycle, which included G2 arrest and a depletion of S-phase populations at FA doses that had no effects in control cells. Proteasome activity diminished p53-Ser15 phosphorylation but was important for FA-induced CHK1 phosphorylation, which is a biochemical marker of DPC proteolysis in replicating cells. Unlike FA, proteasome inhibition had no effect on cell survival and CHK1 phosphorylation by the non-DPC replication stressor hydroxyurea. Overall, we obtained evidence for the importance of proteasomes in protection of human cells against biologically relevant doses of FA. Biochemically, our findings indicate the involvement of proteasomes in proteolytic repair of DPC, which removes replication blockage by these highly bulky lesions.

Keywords: formaldehyde, DNA-protein crosslink, DNA repair, replication, cell cycle

Introduction

Formaldehyde (FA) is a widely used industrial chemical and a ubiquitous atmospheric pollutant. Combustion processes are usually the largest sources of ambient FA but offgassing of plastics, paints and other synthetic materials also generates significant amounts of this toxicant. FA is produced in human body endogenously either as a product of normal metabolism or demethylation of S- or N-methylated xenobiotics in the liver (IARC, 2006; NTP, 2010). A genetically dangerous site of endogenous FA formation is the release of this reactive chemical in the vicinity of DNA during a continuously occurring oxidative demethylation of histones (Walport et al., 2012). Normal plasma levels of FA in humans are in the range of 30–100 μM (IARC, 2006; NTP, 2010). FA was first classified as a human carcinogen based on the increased risks for nasopharyngeal cancers in occupationally exposed populations (IARC, 2006). Recent epidemiological studies have also found a statistically significant association between occupational inhalation exposures to FA and risks of leukemia (Hauptmann et al., 2009; Schwilk et al., 2010). Unlike nasal cancers, the biological plausibility of leukemia causation is controversial, as there was no detectable FA-DNA adducts in the bone marrow of animals exposed to FA via inhalation (Lu et al., 2010).

FA readily reacts with DNA bases producing N-hydroxymethyl adducts with dA and dG, however, these small modifications are hydrolytically unstable (IARC, 2006). The most abundant DNA lesions formed by FA in cells are DNA-protein crosslinks (DPC), which have a much greater chemical stability than small DNA adducts (Quievryn and Zhitkovich, 2000). The dose-dependence of DPC formation and nasal cancers in FA-exposed animals showed a close correlation, leading to the use of DPC in modeling of cancer risks associated with human exposures (Subramaniam et al., 2008). Although it is frequently assumed that DPC are major contributors to FA toxicity, their role in specific toxic responses has not yet been assessed experimentally. The importance of specific lesions for agents producing multiple DNA damage forms can be most directly evaluated through the manipulations of repair processes. In this approach, an increase in toxic responses to the chemical in cells with a lesion-specific repair defect provides evidence for the biological significance of the particular DNA modification.

Characterization of repair mechanisms for DPC has been slower than that for other DNA lesions despite that DPC are formed by common cancer drugs (Loeber et al., 2009; Santi et al., 1984; Taioli et al., 1996) and several human carcinogens (Costa et al., 1997; Macfie et al., 2010; Voitkun and Zhitkovich, 1999). Suppression of DPC removal in FA-treated cells by inhibition of proteasome activity and a normal kinetics of DPC losses in nucleotide excision repair (NER)-deficient human lines has led to a model of DPC repair through the initial proteolysis of crosslinked protein (Quievryn and Zhitkovich, 2000). Cellular repair of DPC formed by chromium(VI) was also sensitive to proteasome inhibition and independent of NER (Zecevic et al., 2010). DPC were also found to be resistant to excision by mammalian NER in vitro (Nakano et al., 2009; Reardon and Sancar, 2006). A very recent study with DPC-containing substrates incubated with Xenopus egg extracts clearly demonstrated a replication-dependent mechanism of DPC repair via ubiquitin-dependent proteolysis (Duxin et al., 2014). These findings are consistent with the virtual absence of active repair of FA-induced DPC in nondividing peripheral blood human lymphocytes (Quievryn and Zhitkovich, 2000). Thus, inhibition of DPC proteolysis in replicating cells can help assess a toxicological importance of these lesions.

In this work, we examined replication recovery, cell cycle changes, genotoxic signaling and survival of human cells treated with low-dose FA under the conditions of proteasome inhibition with the goal of assessing contributions of DPC to specific toxic effects and determining the importance of proteasomes in protection against FA injury.

Materials and Methods

Chemicals

MG132 and bortezomib were obtained from SelleckChem and MG115 was from Santa Cruz. A stock solution of formaldehyde (F8775) and all buffers and salts were from Sigma.

Cells and treatments

Cells were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection. H460 and A549 human lung epithelial cells were cultured under 95% air/5% CO2 humidified atmosphere in 10% serum-supplemented media (RPMI-1640 for H460 and F-12K for A549). IMR90 human normal lung fibroblasts were propagated in DMEM medium containing 10% serum. Primary human fibroblasts were grown in 5% O2 and 5% CO2. Cells were treated with FA in complete growth media for 3 hr.

Western blotting

Attached and floating cells were collected and combined for the preparation of protein extracts. Soluble cellular proteins were obtained as described previously (Reynolds and Zhitkovich, 2007). For detection of histones, cellular proteins were solubilized by boiling cells for 10 min in a 2% SDS buffer (2% SDS, 50 mM Tris-HCl pH 6.8, 10% glycerol, 20 mM N-ethylmaleimide) supplemented with protease and phosphatase inhibitors (Thermo Scientific). Solutions were cooled to room temperature and centrifuged at 10000×g for 10 min to remove occasional debris. Proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE and electrotransferred to ImmunoBlot PVDF membranes. The following primary antibodies were used: anti-histone H3 phosphorylated at Ser10 (9701), anti-CHK1 phosphorylated at Ser317 (2344) and anti-p53 phosphorylated at Ser15 (9284) from Cell Signaling; anti-γ-tubulin (T6557) was from Sigma. Primary antibodies were typically used at 1:1000 dilutions except for anti-histone H3 antibodies that were diluted 1:5000. Secondary antibodies were horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG (12-349, Millipore; 1:5000 dilution) and goat anti-rabbit IgG (7074, Cell Signaling; 1:2000 dilution). Band intensities were quantified by ImageJ and normalized for loading.

Microscopy

Cells were seeded on human fibronectin-coated coverslips and allowed to attach overnight before treatments with 0–150 μM FA for 3 hr in the complete medium. S-phase cells were labeled by incubation with 10 μM 5-ethynyl-2′-deoxyuridine (EdU) for 1 hr prior to the addition of FA. After aspiration of media and a rinse with PBS, cells were fixed with ice-cold methanol for 10 min at 4 C. Next, cells were permeabilized with PBS-0.5% Triton X-100 for 15 min at room temperature. Coverslips were blocked with 2% fetal bovine serum for 1 hr followed by EdU staining using Click-iT EdU-Alexa Fluor 488 Imaging kit (Invitrogen). Mouse monoclonal anti-phospho-histone H2AX (05-636, Millipore) and used at 1:250 dilution. The secondary antibodies were from Life Technologies (A11029 Alexa Fluor 488 goat anti-mouse, 1:500 dilution). All dilutions of antibodies were made in a PBS solution containing 1% BSA and 0.5% Tween-20. Cells were incubated with primary antibodies for 2 hr at 37 C, washed three times with PBS and then incubated with secondary antibodies for 1 hr at room temperature. Coverslips were then mounted on glass slides using a fluorescence mounting media with DAPI (H-1200, Vectashield). Cells were viewed on the Nikon E-800 Eclipse fluorescent microscope.

Fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS)

In experiments analyzing DNA synthesis, IMR90 cells were treated with 0–100 μM FA for 2 hr with the addition of 10 μM EdU for the last hr. For the determination of the delayed cell cycle changes, IMR90 and H460 cells were treated with FA for 3 hr, incubated with 2 μM MG132 for 6 hr and taken for FACS analyses 18 hr later. Cells were collected by trypsinization and fixed overnight in 80% ethanol at 4°C. After washing with PBS, cells were permeabilized with 0.5% Triton X-100 in PBS for 30 min at room temperature and washed with PBS. Cell pellets were resuspended in a Click-iT reaction mixture (Click-iT EdU-Alexa Fluor 488 Flow Cytometry Assay kit from Invitrogen) and incubated for 30 min at room temperature in the dark. Cells were washed once with PBS, resuspended in 500 μl PBS containing 4 μg/ml propidium iodide, and incubated for 30 min at room temperature without light. Cells were washed once again with 2 ml PBS and resuspended in 0.5 ml PBS for flow cytometry (FACSCalibur, BD Biosciences). The CellQuest Pro software package was used for data analysis.

Cytotoxicity

Measurements of the total metabolic activity of cell populations using the CellTiter-Glo luminescent cell viability assay (Promega) were used for the assessment of cytotoxicity. Cells were seeded into 96-well optical cell culture plates (2000 cells/well), grown overnight and then treated with FA for 3 hr. Proteasome inhibitors were added for 6 hr after FA removal. The cytotoxicity assay was performed at 72 hr post-FA.

Clonogenic survival

H460 cells were seeded onto 60-mm dishes (400 cells/dish) and grown overnight. Next day, cells were treated with FA for 3 hr followed by the addition of proteasome inhibitors for 6 hr. Cells were fixed with methanol and Giemsa-stained after 7–8 days of growth. Groups with 30 or more cells were counted as colonies.

Statistics

Two-tailed, unpaired t-test was used for the evaluation of differences between the groups. The p-values for multiple testing were adjusted using the Bonferroni correction. Data in Figures are presented as means±SD. When not visible, error bars were smaller than symbols.

Results

Experimental models

FA is a common product of the combustion of organic matter, which results in the exposure of lung cells to relatively large doses of this carcinogen among tobacco smokers (Hecht, 2003). Therefore, we chose human lung cells as our biological models. A549 and H460 are human lung epithelial cell lines that we have previously examined for repair of FA-induced DPC and cytotoxic mechanisms (Quievryn and Zhitkovich, 2000; Wong et al., 2012). Both cell lines contain wild-type transcriptional factor p53, which plays a major role in DNA damage-induced cell fate decisions, including those triggered by FA (Wong et al., 2012). Since some regulatory networks are altered in all transformed cell lines, signaling responses to FA were investigated in IMR90 normal human lung fibroblasts. We focused our studies on low doses of FA, which ranged from those inducing no or minimal effects in exposed cells to doses producing not more than 50% decline in the colony-forming ability. In addition to their human relevance, low doses help minimize formation and confounding effects of secondary lesions that occur in cells treated with highly toxic concentrations of FA. For example, high FA doses have been found to suppress p53 activation, resulting in a bell-shaped dose response (Wong et al., 2012). The majority of our experiments were conducted with 50–150 μM FA, which covered the physiological range of 30–100 μM FA in human serum of unexposed individuals (IARC, 2006; NTP, 2010) and included a moderately higher dosage of FA occurring locally during inhalation exposures. To mimic in vivo conditions and avoid acute cell injury, our treatments with FA were done in the presence of serum. We primarily employed a widely used proteasome inhibitor MG132 to test a role of proteasomes in cellular responses to FA. Confirmatory experiments were performed with two more inhibitors, MG115 and and bortezomib (PS-341). MG132, MG115 and bortezomib are all reversible inhibitors, which affords a better control of the duration of their action and avoids prolonged inactivation of proteasomes and the resulting cytotoxicity.

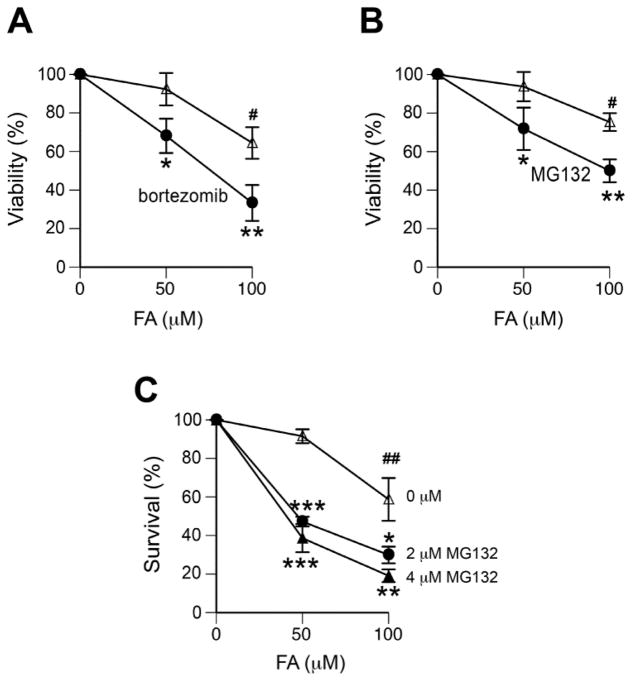

Enhancement of FA toxicity by proteasome inhibition

To assess a role of proteasomes in cytotoxicity of FA, we first measured the overall metabolic activity of cell populations. Cells were treated with FA for 3 hr, then incubated with proteasome inhibitors for 6 hr and allowed to recover for 3 days before viability measurements. We found that the addition of the proteasome inhibitor bortezomib significantly increased cytotoxicity of FA treatments in A549 cells (Fig. 1A), a cell line in which we have previously found a loss of DPC repair by proteasome inactivation (Quievryn and Zhitkovich, 2000). The assessment of MG132 impact on cytotoxicity and clonogenic viability of H460 cells detected strong protective effects of proteasome activity against FA toxicity (Fig. 1B,C). For 50 μM FA, which alone did not produce a significant decrease in the number of colonies, the addition of MG132 caused 50–60% loss in the clonogenic survival of cells.

Figure 1. Proteasome inhibitors enhance FA toxicity in human lung cells.

Cells were treated with FA for 3 hr and then incubated for 6 hr with or without proteasome inhibitors. Cell viability was measured at 72 hr post-FA exposure. Data are from 3–4 experiments. Statistical comparisons were made relative to the corresponding MG132-untreated groups (*-p<0.05, **- p<0.01, ***-p<0.001) and relative to the no-FA controls (#-p<0.05, ##- p<0.01). (A) Effect of 300 nM bortezomib on viability of A549 cells. (B) Effect of 2 μM MG132 on viability of H460 cells. (C) Clonogenic survival of H460 cells incubated with 0, 2 or 4 μM MG132.

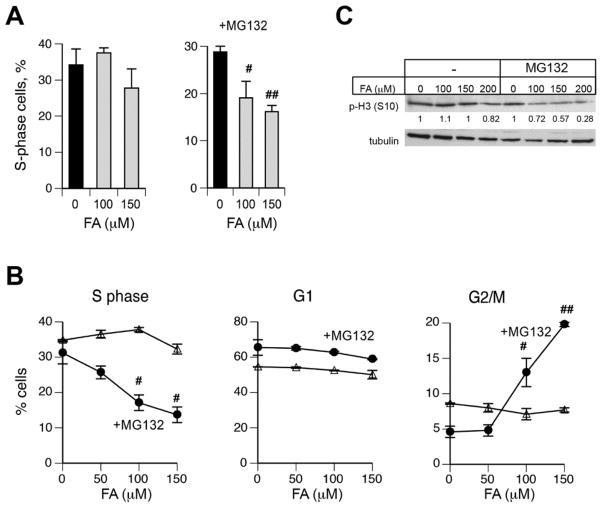

To further explore a role of proteasome activity in FA resistance, we examined cell cycle changes in IMR90 normal human lung fibroblasts. A microscopy-based scoring of EdU-incorporated nuclei revealed significant decreases in the number of replicating IMR90 cells that were treated with FA and MG132 but not with FA alone (Fig. 2A). Cell cycle analyses by FACS confirmed a depletion of IMR90 cells in S-phase by a combined FA+MG132 treatment, which was accompanied by a parallel increase in the frequency of G2/M cells (Fig. 2B). For 150 μM FA, proteasome inhibition caused approximately a 2-fold decrease in the number of S-phase cells and a 4-fold increase in G2/M cells whereas cells treated with FA alone did not show any significant changes. FACS analyses of EdU/DNA-stained cells are unable to differentiate between G2 and mitotic cells, which both have the 4n DNA content and are negative for EdU incorporation. To determine the phase in which IMR90 accumulate after FA+MG132 exposures, we measured the amounts of a mitotic marker, histone H3 phosphorylated at Ser10. Because of a weak attachment of mitotic cells to the dishes, we collected both attached and floating IMR90 cells for the analysis of phospho-histone H3 by western blotting. We found lower levels of this mitotic marker in FA+MG132 samples relative to FA-alone groups (Fig. 2C), indicating a diminished entry of G2 cells into mitosis. Based on these and FACS results, we concluded that proteasome inhibition in FA-treated normal human cells caused a delayed G2 phase arrest.

Figure 2. Effect of proteasome inhibition on cell cycle changes by FA.

IMR90 cells were treated with FA for 3 hr, incubated for 6 hr with 0 or 2 μM MG132 and collected for cell cycle analyses at 18 hr post-MG132. Statistical comparisons relative to FA-untreated controls: #-p<0.05, ##- p<0.01. (A) Percentage of replicating IMR90 cells determined by a manual scoring of EdU-positive nuclei (n=3). (B) Cell cycle changes as determined by FACS (n=2). (C) Western blot for phospho(Ser10)-histone H3. Tubulin is used as a loading control. Numbers below p-H3 blot are normalized band intensities.

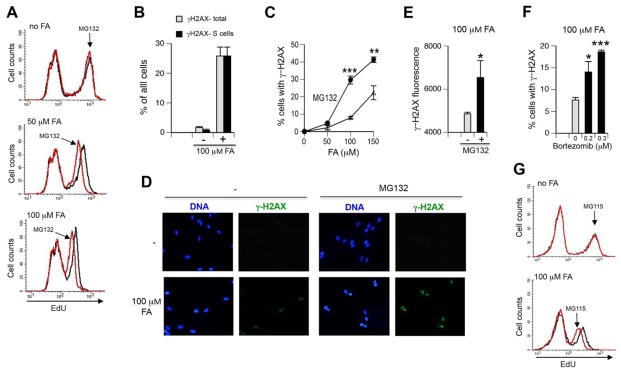

Proteasomes activity and replication stress by FA

G2 cell cycle arrest usually reflects the formation of genomic damage in the preceding S-phase, which activates checkpoint response upon the entry of cells into G2 phase. Therefore, we next investigated DNA synthesis by FACS measurements of incorporation of the base analogue EdU. Consistent with the strong replication-blocking properties of DPC (Duxin et al., 2014), we found that even a low dose of 50 μM FA significantly decreased DNA synthesis, which was further lowered by 100 μM FA (Fig. 3A). Replication inhibition by FA appears to be uniform throughout the S-phase, as evidenced by the lack of changes in the shape of distribution of cells with EdU incorporation (right peaks remaining symmetrical). The addition of MG132 further slowed the rate of DNA replication in FA-treated but not control cells, as evidenced by decreased EdU signals in S-phase populations. To explore how proteasome inhibition is causing inhibition of replication, we analyzed Ser139-phosphorylation of histone H2AX (known as γ-H2AX), which occurs in cells experiencing replication stress (Toledo et al., 2011). Because γ-H2AX is also produced at the sites of DNA breaks in cells outside of S-phase (Lukas et al., 2011), we first investigated the cell cycle distribution of γ-H2AX by costaining with the S-phase marker EdU. We found that all of γ-H2AX-positive IMR90 cells in FA/MG132-treated samples were in S-phase (Fig. 3B), demonstrating the suitability of γ-H2AX for detection of replication stress by FA. The addition of MG132 with FA strongly increased the number of cells with γ-H2AX in comparison to FA-alone samples (Fig. 3C). Furthemore, MG132-treated cells also had larger amounts of γ-H2AX, as evidenced by the increased staining in individual nuclei (Fig. 3D, E). Cotreatments with FA and two concentrations of another proteasome inhibitor bortezomib also significantly elevated the frequency of IMR90 cells with γ-H2AX (Fig. 3F). To further assess the importance of functional proteasomes for DNA replication in FA-treated cells, we examined the effects of a specific inhibitor of the chymotrypsin-like activity of proteasomes, MG115. Similarly to MG132, which inhibits both chymotrypsin-like and post-glutamyl peptide hydrolyse activities, a specific inactivation of the main proteasomal activity by MG115 also decreased the rate of DNA synthesis in FA-treated IMR90 cells (Fig. 3G). Overall, our results on the diminished DNA synthesis and the increased formation of γ-H2AX indicate that proteasome inhibition exacerbated replication stress by FA.

Figure 3. Replication stress in FA-treated IMR90 cells.

MG132 was used at 2 μM. Statistical comparisons were made to the corresponding FA doses without MG132 (*-p<0.05, **- p<0.01, ***-p<0.001). (A) FACS analysis of DNA synthesis in FA and FA+MG132-treated cells. After 1 hr incubation with FA, cells were labeled with 10 μM EdU for 1 hr without FA removal. Right peaks with high EdU incorporation correspond to S-phase cells. Representative profiles from one of two independent experiments are shown. (B) S-phase specificity of γ–H2AX formation in FA/MG132-cotreated cells. Cells were treated with 100 μM FA for 3 hr with EdU addition for the last hour. Data are from two experiments. (C) Frequency of γ–H2AX-containing cells after treatments with FA or FA+MG132 for 3 hr. Background-subtracted values from three experiments are shown. (D) Representative images for γ–H2AX-stained cells treated with 100 μM FA for 3 hr without or with MG132. (E) Quantitation of the intensity of nuclear γ–H2AX staining in 100 μM FA-treated cells. Fluorescence was measured in at least 50 nuclei in each of three experiments. (F) Percentage of γ–H2AX-containing cells after treatments with 100 μM FA alone or FA+bortezomib for 3 hr. Background-subtracted values are shown (n=3). (G) FACS analysis of DNA synthesis in FA and FA+MG115-treated cells. Cells were treated with FA for 1 hr followed by the addition of 10 μM EdU and additional 1 hr incubation without FA removal. Representative profiles from one of two independent experiments are shown.

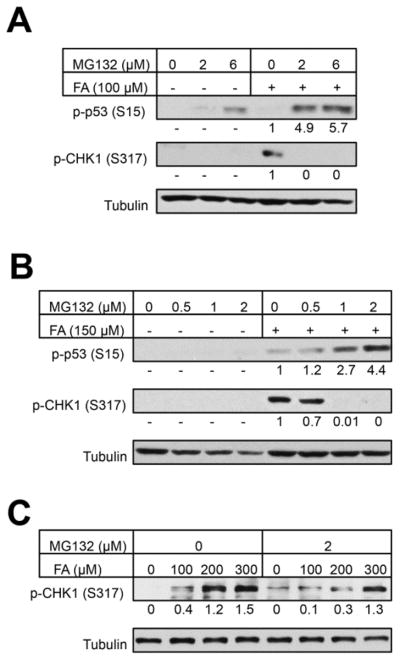

Effect of proteasome inhibition on CHK1 phosphorylation

To better understand how proteasome inhibition enhances replication stress by FA, we examined phosphorylation of checkpoint kinase CHK1. Phosphorylation of this kinase by ATR is strictly dependent on the formation of single-stranded (ss)-DNA regions (Zou and Elledge, 2003), which was confirmed in FA-treated cells (Wong et al., 2012). The appearance of ssDNA and CHK1 phosphorylation during replication of DPC-containing templates required proteolysis of crosslinked protein, which allowed resumption of DNA unwinding but resulted in stalling of DNA polymerase at the sites of residual DNA-peptide crosslinks. Ongoing duplex unwinding despite blocked DNA synthesis in the leading strand generated ssDNA, which triggered CHK1 phosphorylation (Duxin et al., 2014). Thus, CHK1 phosphorylation can serve as a biochemical marker of DPC proteolysis in replicating cells. Western blots of two independent sets of IMR90 lysates showed a complete suppression of CHK1 phosphorylation by FA in the presence of 1–6 μM MG132 (Fig. 4A, B). A clear inhibition of CHK1 phosphorylation by MG132 at low-moderate doses of FA was also observed in H460 cells (Fig. 4C). The suppressive effect of MG132 was lost for the toxic 300 μM FA, which may reflect the incompleteness of proteasome inhibition or a contribution of non-DPC lesions to ATR activation. FA has also been found to induce ATR-mediated phosphorylation of the transcriptional factor p53, which occurred in the ssDNA-independent manner (Wong et al., 2012). Consistent with the postulated helicase blockage-triggered mechanism of p53 activation (Wong et al., 2012), we found that proteasome inhibition produced a dose-dependent increase in p53 phosphorylation by FA (Fig. 4A, B).

Figure 4. CHK1 and p53 phosphorylation in FA-treated cells.

Cells were treated with FA for 3 hr and then incubated for 6 hr with the indicated concentrations of MG132. Tubulin was used as a loading control. Numbers below p-p53 and p-CHK1 blots are background-subtracted, normalized band signals. (A, B) Western blots for phospho-CHK1 and phospho-p53 in IMR90 cells. (C) CHK1 phosphorylation in H460 cells.

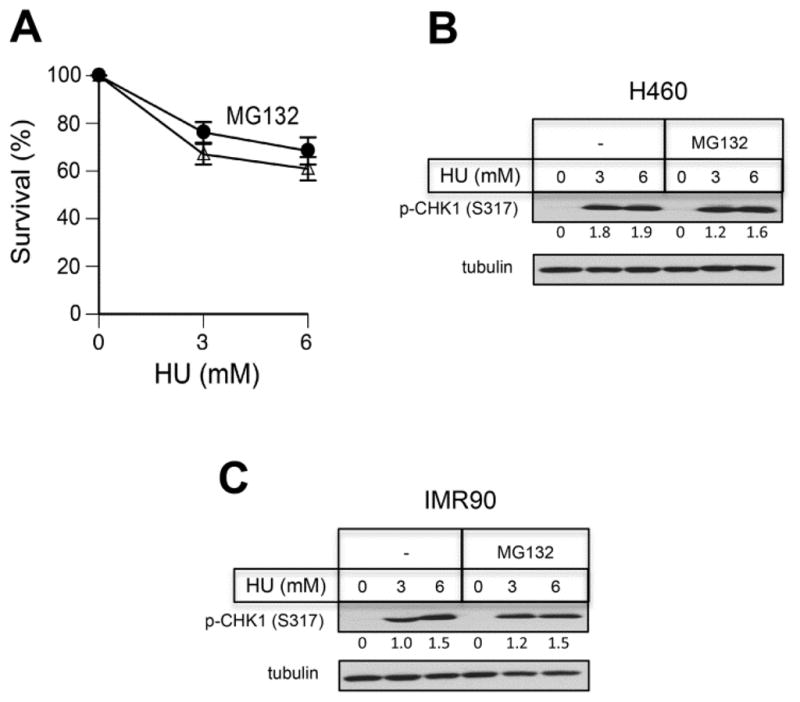

Proteasome activity and responses to hydroxyurea (HU)

Since proteasome inhibition exacerbated replication stress by FA, we wanted to test whether it would also occur for DPC-nonproducing replication stressors. HU is a classic replication stressor that causes inhibition of dNTP synthesis, which results in the stalling of DNA polymerases and accumulation of ssDNA due to ongoing replisome-associated helicase activity. Using the same treatment protocol and the range of toxicity as those for FA (Fig. 1C), we found that MG132 did not decrease survival of HU-treated H460 cells in clonogenic experiments (Fig. 5A). Proteasome inhibition had also no effect on CHK1 phosphorylation by HU in H460 and IMR90 cells (Fig. 5B, C), indicating a lack of MG132 interference with ATR activation by ssDNA that is produced independently of DPC proteolysis.

Figure 5. Proteasome inhibition and responses to hydroxyurea (HU).

(A) Clonogenic survival of H460 cells treated with HU for 3 hr and then incubated for 6 hr with 0 or 2 μM MG132. Data are from three independent experiments with four dishes per dose. (B, C) CHK1 phosphorylation in cells treated with HU in the absence or presence of 2 μM MG132. Tubulin was used as a loading control. Numbers below p-CHK1 blots are tubulin-normalized band intensities.

Discussion

Previous studies of cellular processes promoting recovery from FA-induced injury have been largely focused on canonical DNA repair and DNA damage tolerance mechanisms (de Graaf et al., 2009; Nakano et al., 2009; Ridpath et al., 2007). NER, which is the principal repair mechanism for large DNA adducts (Reardon and Sancar, 2005), did not have a detectable effect on the removal of FA-induced and other DPC in human cells (Quievryn and Zhitkovich, 2000; Zecevic et al., 2010) and it was unable to excise model DPC in vitro (Nakano et al., 2009; Reardon and Sancar, 2006). Mammalian NER in vitro was able to act on small DPC but lost its activity for crosslinks with protein size of approximately 8 kDa (Nakano et al., 2009), which is below molecular weight for histones that are the main crosslinking proteins by FA in cells (Solomon and Varshavsky, 1985). Based on the suppression of DPC removal from FA-treated human cells by inhibition of proteasome activity, it was proposed that DPC repair involves proteolysis of crosslinked proteins and not DNA excision (Quievryn and Zhitkovich, 2000). Cellular repair of other types of chemically induced DPC was also sensitive to inhibition of proteasomes (Baker et al., 2007; Zecevic et al., 2010). However, the proteolysis-based model of DPC repair has been rejected by other investigators who argued that mammalian cells are unable to remove DPC and only possess tolerance mechanisms for these lesions (Ide et al., 2011). A very recent study of DPC substrates in DNA repair- and replication-proficient Xenopus egg extracts provided a clear evidence for an ubiquitin-dependent proteolysis of crosslinked protein, which was required for the restoration of replication (Duxin et al., 2014). The activation of DPC repair was strictly dependent on replication and was triggered by stalling of replicative complexes. For DPC in the leading strand, digestion of crosslinked proteins to peptides allowed resumption of DNA unwinding and DNA synthesis in the lagging strand; however, DNA-peptide crosslinks blocked DNA polymerase in the leading strand. The formation of ssDNA in the leading strand, resulting from uncoupling of DNA unwinding and DNA synthesis, led to CHK1 phosphorylation by ATR (Duxin et al., 2014).

DPC are considered to be the main genotoxic lesions for FA and are used in human risk assessment modeling of FA exposures (Subramaniam et al., 2008). Thus, it is important to understand how human cells can cope with FA-induced DPC. In this work, we investigated the significance of proteasome activity in recovery of human cells from FA-induced injury. Considering a multitude of cellular functions that are controlled by proteasomes, their inhibition can directly or indirectly affect more than one DNA damage tolerance mechanism. We minimized general effects of proteasome inhibition by employing short-term treatments and low concentrations of reversible inhibitors. We found that proteasome activity played a protective role in survival, replication recovery and cell cycle restoration in human cells after low-dose FA treatments. These results are consistent with the involvement of proteasomes in removal of cellular DPC, which are potent replication-blocking lesions (Duxin et al., 2014). Proteasome inhibition in FA-treated cells resulted in delayed G2 arrest, which would be expected for cells exiting S-phase with checkpoint-activating unreplicated DNA regions. Despite the involvement of a different protease, a diminished proteolysis of DPC in yeast was also found to lead to G2 arrest (Stingele et al., 2014). CHK1 phosphorylation, which serves as a biochemical marker of crosslinked protein cleavage during replication of DPC-containing DNA (Duxin et al., 2014), was suppressed by proteasome inhibition in FA-treated cells. Inhibition of proteasome activity did not have any effect on CHK1 phosphorylation by hydroxyurea in our experiments and in other studies with different replication stressors (Sakasai and Tibbetts, 2008). Similarly, increased γ-H2AX formation in the presence of proteasome inhibitors was specific to FA-treated cells, as this marker of genotoxic stress was formed normally in response to non-DPC DNA damage (Murakawa et al., 2007).

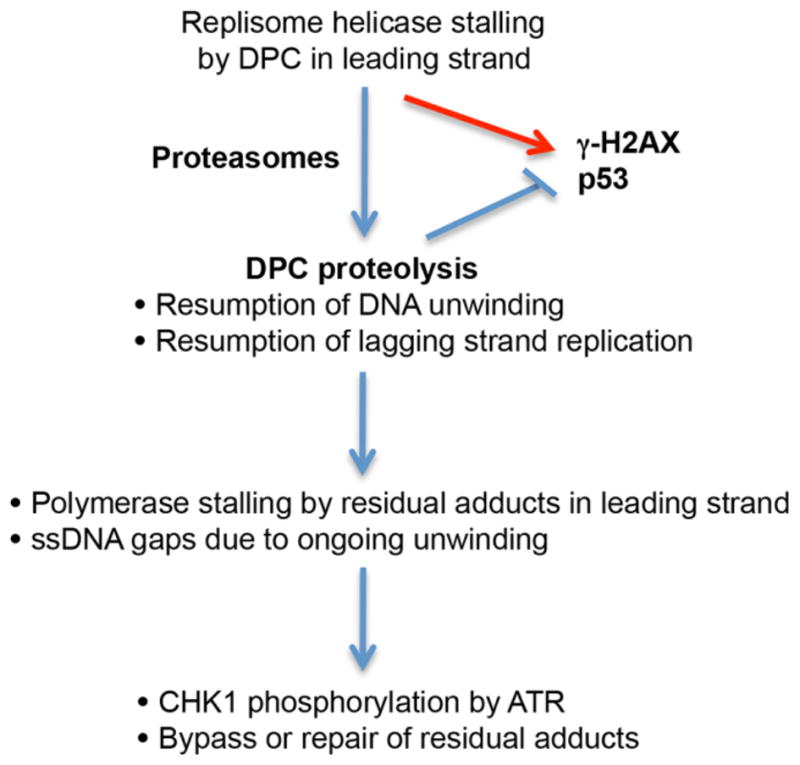

Our experimental findings provide a further support for the proteolysis-based DPC repair mechanism (Duxin et al., 2014; Quievryn and Zhitkovich, 2000; Wong et al., 2012, Zecevic et al., 2010) (Figure 6). In this model, a movement of replisome helicase along the leading strand is blocked by DPC causing replicative stress and phosphorylation of p53 and H2AX. The recruitment of 20S proteasome causes cleavage of crosslinked proteins, which allows a passage of helicase through the residual DNA-peptide crosslinks that then block a more tightly DNA-associated polymerase. Stalling of DNA polymerase under conditions of the ongoing DNA unwinding results in the production of ssDNA gaps in the leading strand, which induces activating phosphorylation of CHK1 by ATR (Duxin et al., 2014; Zou and Elledge, 2003). CHK1 activity plays a well-established pro-survival role in cells experiencing replication stress (Stracker et al., 2009). A lack of specific cellular readouts does not allow us to draw conclusions regarding the role of proteasomes in repair of DPC in the lagging DNA strand. Because the presence of a DPC in the lagging strand blocks DNA synthesis of a single Okazaki fragment (~150 nucleotides long), it has only a very minor effect on the overall replication in comparison to the complete stalling of the replication fork by a DPC in the leading strand (Duxin et al., 2014). Overall, our data demonstrate the importance of proteasome activity in recovery from the primary FA-induced injury, which is blocked DNA replication. Under normal conditions, a proliferative pool of cells in tissues in vivo is limited to stem cells and various progenitors, suggesting that these populations are likely to be particularly dependent on the efficient removal of replication-blocking DPC by proteasomes. It is possible that in addition to repair of DPC, proteasomes also eliminate other cellular proteins damaged by FA, which would be beneficial for both dividing and fully differentiating cells.

Figure 6. Model for the involvement of proteasomes in repair of FA-induced DPC.

The proposed model is based on recent findings by Duxin et al. (2014) and incorporates our current and previous results in FA-treated normal human cells (Wong et al., 2012). The main cause of replication blockage is DPCs in the leading strand, which stall replicative helicase and consequently, inhibit DNA synthesis in both leading and lagging strands. Proteasomes alleviate replication blockage through destruction of crosslinked proteins, which allows replicative helicase to continue duplex unwinding and restores DNA synthesis in the lagging strand. Residual DNA-peptide crosslinks stall DNA polymerase in the leading strand and continuing DNA unwinding generates ss-DNA gaps, triggering ATR-mediated CHK1 phosphorylation. Bypass of residual crosslinks by error-prone polymerases can produce mutations (Minko et al., 2008; Wickramaratne et al., 2015).

Highlights.

Proteasome inhibition enhances cytotoxicity of low-dose FA in human lung cells.

Active proteasomes diminish replication-inhibiting effects of FA.

Proteasome activity prevents delayed G2 arrest in FA-treated cells.

Proteasome inhibition exacerbates replication stress by FA in normal human cells.

Protective role of proteasomes is linked to repair of DNA-protein crosslinks.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grant ES020689 from the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences.

Abbreviations

- DPC

DNA-protein crosslinks

- EdU

5-ethynyl-2′-deoxyuridine

- FACS

fluorescence-activated cell sorting

- FA

formaldehyde

- HU

hydroxyurea

- NER

nucleotide excision repair

- ss

single-stranded

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Baker DJ, Wuenschell G, Xia L, Termini J, Bates SE, Riggs AD, O’Connor TR. Nucleotide excision repair eliminates unique DNA-protein cross-links from mammalian cells. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:22592–225604. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M702856200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa M, Zhitkovich A, Harris M, Paustenbach D, Gargas M. DNA-protein crosslinks produced by various chemicals in cultured human lymphoma cells. J Toxicol Environ Health. 1997;50:433–449. doi: 10.1080/00984109708984000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duxin JP, Dewar JM, Yardimci H, Walter JC. Repair of a DNA-protein crosslink by replication-coupled proteolysis. Cell. 2014;159:346–357. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.09.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Graaf B, Clore A, McCullough AK. Cellular pathways for DNA repair and damage tolerance of formaldehyde-induced DNA-protein crosslinks. DNA Repair (Amst) 2009;8:1207–1214. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2009.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hauptmann M, Stewart PA, Lubin JH, Beane Freeman LE, Hornung RW, Herrick RF, Hoover JF, Fraumeni, Aaron B, Richard BH. Mortality from lymphohematopoietic malignancies and brain cancer among embalmers exposed to formaldehyde. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2009;101:1696–1708. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djp416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hecht SS. Tobacco carcinogens, their biomarkers and tobacco-induced cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2003;3:733–744. doi: 10.1038/nrc1190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- International Agency for Research on Cancer IARC. Formaldehyde. IARC Monogr Eval Carcinog Risks Hum. 2006;88:39–325. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ide H, Shoulkamy MI, Nakano T, Miyamoto-Matsubara M, Salem AM. Repair and biochemical effects of DNA protein crosslinks. Mutat Res. 2011;711:113–122. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2010.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loeber RL, Michaelson-Richie ED, Codreanu SG, Liebler DC, Campbell CR, Tretyakova NY. Proteomic analysis of DNA-protein cross-linking by antitumor nitrogen mustards. Chem Res Toxicol. 2009;22:1151–1162. doi: 10.1021/tx900078y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu K, Collins LB, Ru H, Bermudez E, Swenberg JA. Distribution of DNA adducts caused by inhaled formaldehyde is consistent with induction of nasal carcinoma but not leukemia. Toxicol Sci. 2010;116:441–451. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfq061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lukas J, Lukas C, Bartek J. More than a focus: the chromatin response to DNA damage and its genome integrity maintenance. Nature Cell Biol. 2011;13:1161–1169. doi: 10.1038/ncb2344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macfie A, Hagan E, Zhitkovich A. Mechanism of DNA-protein cross-linking by chromium. Chem Res Toxicol. 2010;23:341–347. doi: 10.1021/tx9003402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minko IG, Kozekov ID, Kozekova A, Harris TM, Rizzo CJ, Lloyd RS. Mutagenic potential of DNA-peptide crosslinks mediated by acrolein-derived DNA adducts. Mutat Res. 2008;637:161–172. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2007.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murakawa Y, Sonoda E, Barber LJ, Zeng W, Yokomori K, Kimura H, Niimi A, Lehmann A, Zhao GY, Hochegger H, Boulton SJ, Takeda S. Inhibitors of the proteasome suppress homologous DNA recombination in mammalian cells. Cancer Res. 2007;67:8536–8543. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-1166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakano T, Katafuchi A, Matsubara M, Terato H, Tsuboi T, Masuda T, Tatsumoto T, Pack SP, Makino K, Croteau DL, Van Houten B, Iijima K, Tauchi H, Ide H. Homologous recombination but not nucleotide excision repair plays a pivotal role in tolerance of DNA-protein cross-links in mammalian cells. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:27065–27076. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.019174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NTP (National Toxicology Program) Final Report on Carcinogens Background Document for Formaldehyde. Rep Carcinog Backgr Doc. 2010 10-5981:i-512. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quievryn G, Zhitkovich A. Loss of DNA-protein crosslinks from formaldehyde-exposed cells occurs through spontaneous hydrolysis and an active repair process linked to proteosome function. Carcinogenesis. 2000;21:1573–1580. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reardon JT, Sancar A. Nucleotide excision repair. Prog Nucleic Acid Res Mol Biol. 2005;79:183–235. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6603(04)79004-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reardon JT, Sancar A. Repair of DNA-polypeptide crosslinks by human excision nuclease. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:4056–4061. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0600538103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds M, Zhitkovich A. Cellular vitamin C increases chromate toxicity via a death program requiring mismatch repair but not p53. Carcinogenesis. 2007;28:1613–1620. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgm031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ridpath JR, Nakamura A, Tano K, Luke AM, Sonoda E, Arakawa H, Buerstedde JM, Gillespie DA, Sale JE, Yamazoe M, Bishop DK, Takata M, Takeda S, Watanabe M, Swenberg JA, Nakamura J. Cells deficient in the FANC/BRCA pathway are hypersensitive to plasma levels of formaldehyde. Cancer Res. 2007;67:11117–11122. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-3028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakasai R, Tibbetts R. RNF8-dependent and RNF8-independent regulation of 53BP1 in response to DNA damage. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:13549–13555. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M710197200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santi DV, Norment A, Garrett CE. Covalent bond formation between a DNA-cytosine methyltransferase and DNA containing 5-azacytosine. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1984;81:6993–6997. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.22.6993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwilk E, Zhang L, Smith MT, Smith AH, Steinmaus C. Formaldehyde and leukemia: an updated meta-analysis and evaluation of bias. J Occup Environ Med. 2010;52:878–886. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0b013e3181ef7e31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solomon MJ, Varshavsky A. Formaldehyde-mediated DNA-protein crosslinking: a probe for in vivo chromatin structures. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1985;82:6470–6474. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.19.6470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stingele J, Schwarz MS, Bloemeke N, Wolf PG, Jentsch S. A DNA-dependent protease involved in DNA-protein crosslink repair. Cell. 2014;158:327–338. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.04.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stracker TH, Usui T, Petrini JHJ. Taking the time to make important decisions: the checkpoint effector kinases Chk1 and Chk2 and the DNA damage response. DNA Repair. 2009;8:1047–1054. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2009.04.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subramaniam RP, Chen C, Crump KS, Devoney D, Fox JF, Portier CJ, Schlosser PM, Thompson CM, White P. Uncertainties in biologically-based modeling of formaldehyde-induced respiratory cancer risk: identification of key issues. Risk Anal. 2008;28:907–923. doi: 10.1111/j.1539-6924.2008.01083.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taioli E, Zhitkovich A, Toniolo P, Bernstein J, Blum R, Costa M. DNA-protein crosslinks as a biomarker of cis-platinum activity in cancer patients. Oncol Rep. 1996;3:439–441. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toledo LI, Murga M, Zur R, Soria R, Rodriguez A, Martinez S, Oyarzabal J, Pastor J, Bischoff JR, Fernandez-Capetillo O. A cell-based screen identifies ATR inhibitors with synthetic lethal properties for cancer-associated mutations. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2011;18:721–727. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voitkun V, Zhitkovich A. Analysis of DNA-protein crosslinking activity of malondialdehyde in vitro. Mutat Res. 1999;424:97–106. doi: 10.1016/s0027-5107(99)00011-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walport LJ, Hopkinson RJ, Schofield CJ. Mechanisms of human histone and nucleic acid demethylases. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2012;16:525–534. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2012.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wickramaratne S, Boldry EJ, Buehler C, Wang YC, DiStefano MD, Tretyakova NY. Error-prone translesion synthesis past DNA-peptide crosslinks conjugated to the major groove of DNA via C5 of thymidine. J Biol Chem. 2015;290:775–787. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.613638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong VC, Cash HL, Morse JL, Lu S, Zhitkovich A. S-phase sensing of DNA-protein crosslinks triggers TopBP1-independent ATR activation and p53-mediated cell death by formaldehyde. Cell Cycle. 2012;11:2526–2537. doi: 10.4161/cc.20905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zecevic A, Hagan E, Reynolds M, Poage G, Johnston T, Zhitkovich A. XPA impacts formation but not proteasome-sensitive repair of DNA-protein cross-links induced by chromate. Mutagenesis. 2010;25:381–388. doi: 10.1093/mutage/geq017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zou L, Elledge SJ. Sensing DNA damage through ATRIP recognition of RPA-ssDNA complexes. Science. 2003;300:1542–1548. doi: 10.1126/science.1083430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]