Abstract

Hyperoxia contributes to the development of bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD) in premature infants. Activation of the aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR) protects adult and newborn mice against hyperoxic lung injury by mediating increases in the expression of phase I (cytochrome P450 (CYP) 1A) and phase II (NADP(H) quinone oxidoreductase (NQO1)) antioxidant enzymes (AOE). AhR positively regulates the expression of RelB, a component of the nuclear factor-kappaB (NF-κB) protein that contributes to anti-inflammatory processes in adult animals. Whether AhR regulates the expression of AOE and RelB, and protects fetal primary human lung cells against hyperoxic injury is unknown. Therefore, we tested the hypothesis that AhR-deficient fetal human pulmonary microvascular endothelial cells (HPMEC) will have decreased RelB activation and AOE, which will in turn predispose them to increased oxidative stress, inflammation, and cell death compared to AhR-sufficient HPMEC upon exposure to hyperoxia. AhR-deficient HPMEC showed increased hyperoxia-induced reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation, cleavage of poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP), and cell death compared to AhR-sufficient HPMEC. Additionally, AhR-deficient cell culture supernatants displayed increased macrophage inflammatory protein 1α and 1β, indicating a heightened inflammatory state. Interestingly, loss of AhR was associated with a significantly attenuated CYP1A1, NQO1, superoxide dismutase 1(SOD1), and nuclear RelB protein expression. These findings support the hypothesis that decreased RelB activation and AOE in AhR-deficient cells is associated with increased hyperoxic injury compared to AhR-sufficient cells.

Keywords: Aryl hydrocarbon Receptor, Fetal Human Pulmonary Microvascular Endothelial Cells, Hyperoxic Injury, Oxidant Stress, Antioxidant enzymes, RelB

Introduction

Supplemental oxygen is commonly administered as an important and life-saving measure in patients with impaired lung function. Although delivery of enriched oxygen relieves the immediate life-threatening consequences transiently, it may also exacerbate lung injury (Thiel et al., 2005). Excessive oxygen exposure and lung-stretching lead to increased reactive oxygen species (ROS) production and expression of proinflammatory cytokines (Jobe et al., 2008). ROS react with nearby molecules (e.g., protein, lipids, DNA, and RNA) and modify their structure and function (Bhandari et al., 2006), resulting in both acute and chronic pulmonary toxicities. The antioxidant defense system develops late in gestation, making preterm neonates highly susceptible to oxidative stress (Vina et al., 1995; Asikainen and White, 2005). Bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD) remains the most prevalent, and one of the most serious long-term sequelae of preterm birth, affecting approximately 14,000 preterm infants born each year in United States (Fanaroff et al., 2007; Van Marter, 2009). Evidence implicates hyperoxia induced generation of ROS and lung inflammation as major contributors in the development of BPD and its sequelae (Saugstad, 2003). Infants with BPD are more likely to have long-term pulmonary problems, increased re-hospitalizations during the first year of life, and delayed neurodevelopment (Short et al., 2003; Fanaroff et al., 2007). Hence, there is an urgent need for improved therapies to prevent BPD.

The aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR) is a member of basic - helix – loop – helix / PER – ARNT – SIM family of transcriptional regulators (Burbach et al., 1992; Sogawa and Fujii-Kuriyama, 1997; Beischlag et al., 2008). In humans, the AhR is highly expressed in the lungs, thymus, kidney and liver (Tirona and Kim, 2005). The AhR is predominantly cytosolic, localized in a core complex comprising two molecules of 90-kDa heat shock protein and a single molecule of the co-chaperone hepatitis X-associated protein-2 (Denis et al., 1988; Carver and Bradfield, 1997). AhR activation results in a conformational change of the cytosolic AhR complex that exposes a nuclear localization sequence(s), resulting in translocation of this complex into the nucleus (Hord and Perdew, 1994; Pollenz et al., 1994). In the nucleus, AhR dissociates from the core complex, dimerizes with the AhR nuclear translocator, and initiates transcription of many phase I and phase II antioxidant enzymes (AOE) such as cytochrome P450 (CYP) 1A1, glutathione S-transferase- (GST-α), and NAD(P)H quinone reductase-1 (NQO1), by its interaction with the xenobiotic responsive elements present in the promoter region of these genes (Fujisawa-Sehara et al., 1987; Rushmore et al., 1990; Favreau and Pickett, 1991; Emi et al., 1996).

We reported that AhR-deficient adult mice are more susceptible to hyperoxic lung injury that is associated with a lack of expression of pulmonary and hepatic CYP1A subfamily of enzymes (Couroucli et al., 2002; Jiang et al., 2004). Recently, we also observed that newborn AhR dysfunctional (AhRd) mice have a similar susceptibility to hyperoxic lung injury that is associated with decreases in the expression of phase I (CYP 1A) and phase II (NQO1 and microsomal glutathione S-transferase 1) AOE (Shivanna et al., 2013). Additionally, other investigators have found that AhR-deficient mice have an increased inflammatory response in their lungs on exposure to cigarette smoke or bacterial endotoxin (Thatcher et al., 2007; Baglole et al., 2008; de Souza et al., 2014), suggesting that AhR activation mediates processes suppressing lung inflammation. Evidence indicates that AhR exerts its anti-inflammatory effects in part by positively regulating the expression of nuclear RelB (Thatcher et al., 2007; Baglole et al., 2008; Vogel et al., 2013; de Souza et al., 2014). RelB, a member of alternative nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (NF-κB) pathway signaling proteins, is known to inhibit inflammatory processes by modulating the expression of various chemokines and cytokines (Weih et al., 1995; Xia et al., 1997; Yoza et al., 2006; Martucci et al., 2007; Spinelli et al., 2014).

The observations in animals do not indicate cell specific effects nor do they indicate whether RelB modulates hyperoxic lung injury. Thus, the goals of this study were to investigate the effects of AhR signaling on hyperoxia-induced oxidative stress, inflammatory gene expressions, cell death, and expressions of antioxidant enzymes and RelB in fetal human lung cells in vitro. Specifically, we chose the fetal human pulmonary microvascular endothelial cells (HPMEC) for our experiments because they are susceptible to hyperoxic injury and they express AhR (Zhang and Walker, 2007). In addition, Wright et al. (Wright et al., 2010) have demonstrated the feasibility of using HPMEC to examine mechanism(s) of hyperoxic injury in cells derived from human neonatal lungs. Using these cells, we tested the hypothesis that AhR-deficient HPMEC will have decreased RelB activation and AOE, which will in turn predispose them to increased oxidative stress, inflammation, and cell death compared to AhR-sufficient HPMEC upon exposure to hyperoxia.

Materials and Methods

Cell culture

HPMEC, the primary microvascular endothelial cells derived from the lungs of human fetus were obtained from ScienCell research laboratories (San Diego, CA; 3000). HPMEC were grown in 95% air and 5% CO2 at 37ºC in specific endothelial cell medium according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

Small interfering RNA (siRNA) transfections

HPMEC were seeded in fibronectin-coated 60 mm, 6-well, or 96-well plates at 60-70% confluence 24 h before transfection. Transfections were then performed with either 50 nM control siRNA (Dharmacon, Lafayette, CO; d-001810) or 50 nM AhR specific siRNA (Dharmacon, Lafayette, CO; L-004990) using LipofectamineRNAiMAX (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY; 13778030). Twenty four hours after transfections, the cells were exposed to air or hyperoxia for up to 48 h. siRNA mediated knockdown of AhR was validated by determining the expression of AhR mRNA and protein by real time RT PCR analysis and western blotting, respectively. Additionally, cells were harvested and analyzed for viability, proliferation, apoptosis and necrosis, ROS generation, inflammatory gene expressions, and AhR and NFkB activation.

Exposure of cells to hyperoxia

Hyperoxia experiments were conducted in a plexiglass, sealed chamber into which a mixture of 95% O2 and 5% CO2 was circulated continuously as reported (Shivanna et al., 2011a).

Determination of Functional Activation of AhR

It is widely established that functional activation of AhR results in its translocation into the nucleus, which results in transcriptional activation of phase I and phase II detoxification enzymes such as CYP1A1 and NQO1. Therefore, we determined the functional activation of AhR by analyzing the expression of nuclear AhR apoprotein, and CYP1A1 and NQO1 mRNA and apoprotein levels.

Western Blot Assays

Whole-cell, nuclear and cytoplasmic protein extracts from the transfected cells exposed to air or hyperoxia were obtained by using nuclear extraction kit (Active Motif, Carlsbad, CA; 40010) according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Shivanna et al., 2011a). β-actin and lamin B were used as reference proteins for the cytoplasmic and nuclear fractions, respectively. The protein extracts were separated by 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes. The membranes were incubated overnight at 4°C with the following primary antibodies: anti-AhR antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnologies, Santa Cruz, CA; sc-5579, dilution 1:500), anti-CYP1A1 antibody (gift from P.E. Thomas, Rutgers University, Piscataway, NJ, dilution 1:500), anti-NQO1 antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnologies, Santa Cruz, CA; sc-16464, dilution 1:500), anti-β-actin antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnologies, Santa Cruz, CA; sc-47778, dilution 1:1000), anti-hemoxygenase-1 (HO-1) (Enzo Life Sciences, Farmingdale, NY; ADI-SPA-896F, dilution 1:500), anti-superoxide dismutase-1 (SOD-1) (Santa Cruz Biotechnologies, Santa Cruz, CA; sc-8637, dilution 1:500), anti-cleaved poly ADP ribose polymerase (Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA; 9541, dilution 1:1000), anti-RelB (Santa Cruz Biotechnologies, Santa Cruz, CA; sc-226, dilution 1:500), anti-p65 (Santa Cruz Biotechnologies, Santa Cruz, CA; sc-109, dilution 1:500), and anti-lamin B (Santa Cruz Biotechnologies, Santa Cruz, CA; sc-6216, dilution 1:500) antibodies. The primary antibodies were detected by incubation with the appropriate horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies. The immuno-reactive bands were detected by chemiluminescence methods and the band density was analyzed by Kodak 1D 3.6 imaging software (Eastman Kodak Company, Rochester, NY).

Real-time RT-PCR assays

Control or AhR siRNA transfected HPMEC were grown in 6 well plates and exposed to air or hyperoxia as described above. At 24 and 48 h of exposure, total RNA was isolated and reverse transcribed to cDNA as mentioned before (Shivanna et al., 2011a). Real-time quantitative RT-PCR analysis was performed with 7900HT Real-Time PCR System using iTaq Universal SYBR Green Supermix (Biorad, Hercules, CA; 1725121). The sequences of the primer pairs were hAhR: 5′- CACCGATGGGAAATGATACTATCC-3′ and 5′- GGTGACCTCCAGCAAATGAGTT -3′; hCYP1a1: 5'-TGGATGAGAACGCCAATGTC-3' and 5'-TGGGTTGACCCATAGCTTCT-3'; hNQO1: 5'-ACGCCC-GAATTCAAATCCT-3’ and 5'- CCTGCCTGGAAGTTTAGGTCAA-3'; hHO1: 5'-AGGCCAAGACTGCGTTCC-3’ and 5'- GCAGAATCTTGCACTTTGTTGCT-3’; hSOD1: 5'-TCAGGAGACCATTGCATCATT-3’ and 5'- CGC TTT CCT GTC TTT GTA CTT TCT TC-3’; hβ-actin: 5'- TGACGTGGACATCCGCAAAG-3' and 5'-CTGGAAGGTGGACAGCGAGG-3'. β-actin was used as the reference gene. The ΔΔCt method was used to calculate the fold change in mRNA expression: ΔCt = Ct (target gene) - Ct (reference gene), ΔΔCt = ΔCt (treatment) - ΔCt (control), fold change = 2(−ΔΔCt).

Cell Viability Assay

Cell viability was determined by a colorimetric assay based on the ability of viable cells to reduce the tetrazolium salt, MTT (3-(4, 5-dimethylthiazolyl-2)-2, 5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide), to formazan. HPMEC were seeded onto 96-well microplates, transfected with control or AhR siRNA, followed by exposure to air or hyperoxia for up to 48 h. The cell viability was then assessed by MTT reduction assays as outlined in the MTT Assay protocol (American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, VA).

Cell Proliferation Assay

Cell proliferation was determined based on the measurement of cellular DNA content via fluorescent dye binding using the CyQUANT NF cell proliferation assay kit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA; C35006) as per the manufacturer’s recommendations. HPMEC seeded onto 96- well microplates were grown to 60-70% confluence, before being transfected with 50 nM control or AhR siRNA. After 24 h of transfection, the cells were exposed to air or hyperoxia for up to 48 h. At the end of experiments, the medium was gently aspirated, and the cells were incubated for 30 minutes with 100 µl of 1X dye binding solution per well. Following the incubation, the fluorescence intensity of each sample was measured using Spectramax M3 fluorescence microplate reader with excitation at 485 nm and emission detection at 530 nm.

Apoptosis and Necrosis Assay

During apoptosis, phosphatidylserine (PS) translocates from the inner to external surface of the cell membrane. Annexin V, a phospholipid binding protein, can be used to identify this process since it has a high affinity for PS. Propidium iodide (PI) is a nucleic acid binding dye that is impermeant to live cells and apoptotic cells, but stains necrotic cells by binding tightly to the nucleic acids in the cell. Thus, apoptosis and necrosis were estimated by flow cytometry using FITC Annexin V/Dead cell apoptosis kit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA; V13242) as per the manufacturer’s protocol. Briefly, HPMEC grown in 6-well plates were transfected with 50 nM control or AhR siRNA, and exposed to air or hyperoxia for 48 h as described above. At the end of the experiments, the cells were washed with cold phosphate-buffered saline and resuspended in 1X annexin-binding buffer, before adding FITC annexin V and propidium iodide (PI) and incubating them at room temperature for 15 minutes. The cells were then mixed with additional 1X annexin-binding buffer, placed on ice, and immediately analyzed by flow cytometry on a FACS LSR II (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) with the associated software (Cell Quest).

Measurement of ROS generation

Intracellular levels of ROS were quantified by the ROS sensitive fluorophore 5-(and-6)- chloromethyl-2’, 7’-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate (CM-H2DCF-DA) according to the manufacturer’s recommendation (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA; C6827). Briefly, the transfected cells grown in 6-well plates were exposed to air or hyperoxia for 24 h, following which they were incubated with 5µM CM-H2DCF-DA and analyzed by flow cytometry on a FACS LSR II (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) with the associated software (Cell Quest).

Measurement of cytokine/chemokine production: Multiplex Luminex Assay

The cell culture supernatants transfected with control or AhR siRNA and exposed to air or hyperoxia for up to 48 h, were analyzed for cytokine/chemokine levels using Millipore Human Cytokine/Chemokine assay as per the manufacturer’s recommendations. The following cytokines/chemokines were analyzed: Epidermal growth factor (EGF), Interferon (IFN) α2, IFNγ, interleukin (IL)-10, IL-17A, IL-1RA, IL-1α, IL-1β, IL-2, IL-6, monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1), macrophage inflammatory protein (MIP)-1α, MIP-1β, tumor necrosis factor (TNF) α, and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF).

Analyses of data

The results were analyzed by GraphPad Prism 5 software. At least three separate experiments were performed for each measurement, and the data are expressed as means ± SEM. The effects of AhR gene expression, exposure, and their associated interactions for the outcome variables were assessed using ANOVA techniques. Multiple comparison testing by the posthoc Bonferroni test was performed if statistical significance of either variable or interaction was noted by ANOVA. A p value of <0.05 was considered significant.

Results

In this study, we investigated the role of AhR signaling in hyperoxic injury in the human fetal lung derived HPMEC.

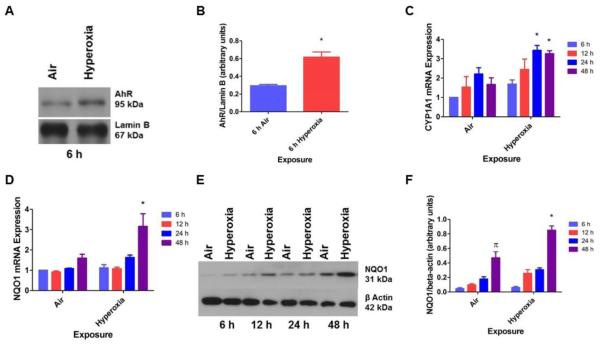

Hyperoxia increased functional activation of the AhR

To determine whether AhR plays a mechanistic role in hyperoxic injury in HPMEC, we initially performed studies to elucidate the effects of hyperoxia on AhR activation. It has been observed that activation of AhR results in its translocation from the cytoplasm to the nucleus and to transcriptionally activate the expression of phase I (CYP1A1) and II (NQO1) enzymes. So, we fractionated the cytoplasmic and nuclear proteins of the cell lysates and then analyzed the amounts of AhR in each fraction by western blotting. Hyperoxia increased nuclear localization of AhR protein in HPMEC (Figs. 1A and B). Additionally, real-time RT-PCR analysis of the RNA extracted from these cells showed that hyperoxia increased CYP1A1 (Fig. 1C) and NQO1 (Fig. 1D) mRNA and NQO1 (Figs. 1E and F) protein expression.

Figure 1. Hyperoxia functionally activates AhR in HPMEC.

HPMEC were exposed to air or hyperoxia for up to 48 h. The cell lysates were separated into cytoplasmic and nuclear fractions at the indicated time points, and western blotting was performed using anti-AhR, anti-NQO1, anti-β-actin, or anti-lamin B antibodies. (A) Representative western blot showing nuclear AhR apoprotein expression. (B) Densitometric analysis of the nuclear AhR apoprotein and lamin B. RNA, isolated at 6, 12, 24 and 48 h of exposure, was subjected to real-time RT-PCR analysis of CYP1A1 (C) and NQO1 (D) mRNA. (E) Representative western blot showing cytoplasmic NQO1 protein expression. (F) Densitometric analysis of the cytoplasmic NQO1 protein and β- actin. Data are representative of at least three independent experiments. Values are presented as means ± SEM (n=3). Two-way ANOVA showed an effect of hyperoxia and time of exposure and an interaction between them for NQO1 expression, and an effect of hyperoxia without any interaction for CYP1A1 mRNA expression in this figure. *, p < 0.05 vs. air exposed cells.

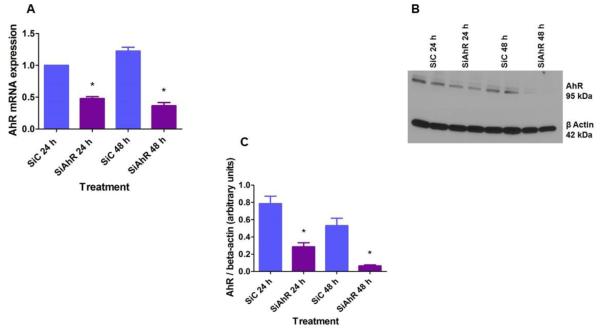

AhR siRNA efficiently silenced AhR mRNA and protein expression in HPMEC

To investigate whether the AhR regulates hyperoxic injury in fetal human lung cells in vitro, we initially performed AhR siRNA transfection experiments in HPMEC to knockdown AhR. As expected, AhR siRNA significantly decreased the expression of both AhR mRNA (Fig. 2A) and protein (Figs. 2B and C).

Figure 2. Validation of siRNA mediated knockdown of AhR in HPMEC.

HPMEC were transfected with either 50 nM control (SiC) or AhR (SiAhR) siRNA. Twenty-four hours after transfection, cells were exposed to air for up to 48 h. RNA was extracted at the indicated time points for real-time RT-PCR analyses of AhR mRNA (A) expression. The whole-cell protein extract was used for western blot analysis with the anti-AhR or anti-β-actin antibodies (B). AhR band intensities were quantified and normalized to β-actin (C). Data are representative of at least three independent experiments. Values are presented as means ± SEM (n=3). *, p < 0.05 vs. control siRNA.

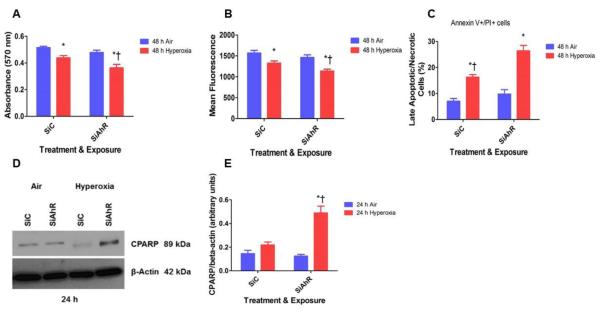

AhR deficiency increased hyperoxia-induced cytotoxicity in HPMEC:

The MTT activity reflects the mitochondrial activity of the cells, and thus the absorbance measured reflects the cell viability. Hyperoxia caused cytotoxicity, as reflected by a decrease in the cellular capacities to reduce MTT. However, AhR-deficient cells had significantly increased hyperoxia-induced cytotoxicity compared to AhR-sufficient cells (Fig. 3A).

Figure 3. AhR deficiency potentiates hyperoxia-induced cytotoxicity in HPMEC.

Control (SiC) or AhR (SiAhR) siRNA transfected HPMEC were exposed to air or hyperoxia for up to 48 h, following which: (A) cell viability was assessed by MTT (3-(4, 5-dimethylthiazolyl-2)-2, 5- diphenyltetrazolium bromide) reduction activities; (B) cell proliferation was determined based on the measurement of cellular DNA content via fluorescent dye binding using the CyQUANT NF cell proliferation assay; (C) cell necrosis and apoptosis was determined by annexin V and propidium iodide staining of the cells as measured by flow cytometry. Cell apoptosis was also determined by western blotting with anti-cleaved poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase (CPARP) and anti- β-actin antibodies (D), and normalizing CPARP to β-actin band intensities (E). Values are presented as means ± SEM (n=4). Data are representative of at least three independent experiments. Two-way ANOVA showed an effect of hyperoxia and AhR gene and an interaction between them for all the dependent variables, except for CPARP in this figure. Significant differences between air- and hyperoxia-exposed cells are indicated by *, p < 0.05. Significant differences between hyperoxia-exposed AhR-sufficient and –deficient cells are indicated by †, p < 0.05.

AhR deficiency augmented hyperoxia-mediated inhibition of HPMEC proliferation

Oxidant-stress such as hyperoxia is well known to inhibit cell proliferation in general. Accordingly, CyQUANT NF cell proliferation assay showed that hyperoxia inhibited proliferation of HPMEC by 15%. However, AhR knockdown increased this inhibitory effect, wherein hyperoxia decreased cell proliferation by 27% (Fig. 3B).

AhR-deficient cells had increased apoptosis

To determine the mechanisms of cytotoxicity in our in vitro model, we evaluated the severity of cellular apoptosis and necrosis. Hyperoxia increased late apoptosis and necrosis in HPMEC, and these effects were significantly exacerbated in AhR-deficient cells compared to AhR- sufficient cells (Fig. 3C). Furthermore, AhR-deficient cells exposed to hyperoxia had increased cleaved poly (ADP-ribose) (PARP) polymerase protein expression (Figs. 3D and E), which is a marker of underlying apoptosis (Oliver et al., 1998).

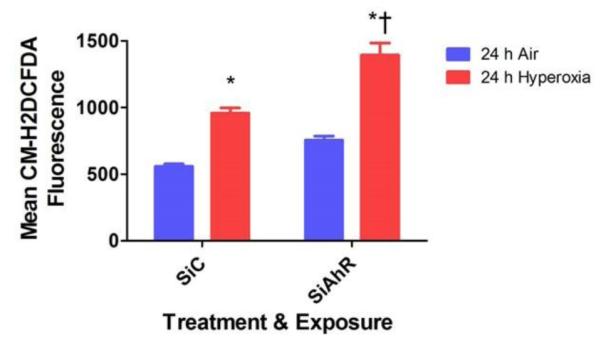

AhR deficiency increased hyperoxia-induced generation of ROS in HPMEC

Hyperoxia-induced generation of ROS has been widely implicated in the pathogenesis of hyperoxic lung injury. To determine whether AhR signaling regulates ROS production, intracellular ROS levels were measured by flow cytometry after the cells were stained with the redox-sensitive dye CM-H2DCF-DA. Not surprisingly, hyperoxia increased ROS generation. In AhR-deficient cells, hyperoxia augmented ROS levels compared to AhR-sufficient cells (Fig. 4).

Figure 4. AhR deficiency potentiates hyperoxia-induced ROS generation in HPMEC.

Control (SiC) or AhR (SiAhR) siRNA transfected HPMEC were exposed to air or hyperoxia for 24 h, following which the oxidation of the fluorescent dye, CM-H2DCF-DA, was measured by flow cytometry. The graph represents the mean CM-H2DCF fluorescence intensity for at least three independent experiments. Values are presented as means ± SEM (n=4). Two-way ANOVA showed an effect of hyperoxia and AhR gene and an interaction between them for the dependent variable in this figure. Significant differences between air- and hyperoxia-exposed cells are indicated by *, p < 0.05. Significant differences between hyperoxia-exposed AhR-sufficient and –deficient cells are indicated by †, p < 0.05.

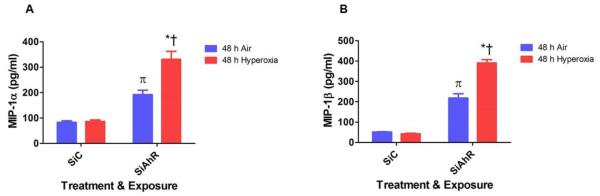

AhR deficiency increased inflammation in HPMEC

We determined the levels of EGF, IFN α2, IFNγ, IL-10, IL-17A, IL-1RA, IL-1α, IL-1β, IL-2, IL- 6, MCP-1, MIP-1α, MIP-1β, TNF α, and VEGF in the cell culture supernatants by multiplex luminex assay to evaluate the impact of AhR signaling on hyperoxia-induced inflammatory responses. Since the HPMEC culture medium had significantly elevated EGF and VEGF levels, these two cytokine/chemokines were not analyzed. Interestingly, in our in vitro model, hyperoxia-increased the levels of MIP-1α (Fig. 5A) and MIP-1β (Fig. 5B), and this phenomenon was further enhanced in AhR-deficient cells. Hyperoxia did not affect the expression of the other cytokines measured at the 48 h time point in our model (Table 1).

Figure 5. AhR deficiency potentiates hyperoxia-induced MIP-1α and MIP-1β concentrations in HPMEC.

Control (SiC) or AhR (SiAhR) siRNA transfected HPMEC were exposed to air or hyperoxia for 48 h, following which the cell free supernatants were analyzed for cytokines/chemokines by multiplex luminex assay. The graph represents the mean MIP-1α (A) and MIP-1β (B) concentrations for at least three independent experiments. Values are presented as means ± SEM (n=4). Two-way ANOVA showed an effect of hyperoxia and AhR gene and an interaction between them for all the dependent variables in this figure. Significant differences between air- and hyperoxia-exposed cells are indicated by *, p < 0.05. Significant differences between hyperoxia-exposed AhR-sufficient and –deficient cells are indicated by †, p < 0.05. Significant differences between air-exposed AhR-sufficient and –deficient cells are indicated by π, p < 0.05.

Table 1.

Quantitative effects of hyperoxia on cytokine/chemokine levels in HPMEC

| Cytokine/chemokine (pg/ml) |

SiC-Air | SiAhR-Air | SiC-Hyperoxia | SiAhR-Hyperoxia |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IFN-α2 | 73.0 ± 2.7 | 66.7 ± 3.2 | 68.2 ± 2.6 | 73.5 ± 3.3 |

| IFN-γ | 25.1 ± 1.7 | 23.8 ± 1.5 | 24.0 ± 1.5 | 24.3 ± 0.2 |

| IL-10 | 4.1 ± 0.4 | 4.8 ± 0.4 | 4.1 ± 0.5 | 4.5 ± 0.6 |

| IL-17A | 2.6 ± 0.3 | 2.6 ± 0.3 | 1.9 ± 0.1 | 2.5 ± 0.1 |

| IL-1RA | 50.6 ± 4.5 | 49.3 ± 4.5 | 40.2 ± 1.3 | 46.4 ± 5.9 |

| IL-1α | 157.2 ± 9.0 | 153.8 ± 5.0 | 135.8 ± 14.4 | 131.7 ± 20.9 |

| IL-1β | 4.5 ± 0.2 | 3.8 ± 0.2 | 4.9 ± 0.3 | 4.0 ± 0.2 |

| IL-2 | 3.3 ± 0.3 | 3.2 ± 0.4 | 2.7 ± 0.2 | 2.9 ± 0.3 |

| MCP-1 | 6188.0 ± 237.3 | 5859.0 ± 283.8 | 5427.0 ± 170.7 | 5330.0 ± 38.0 |

| TNF-α | 183.6 ± 28.6 | 174.2 ± 15.8 | 177.8 ± 9.0 | 167.8 ± 20.1 |

Control (SiC) or AhR (SiAhR) siRNA transfected HPMEC were exposed to air or hyperoxia for 48 h, following which the cell free supernatants were analyzed for the above cytokines/chemokines by multiplex luminex assay. Data are expressed as means ± SEM. There were no statistically significant differences in the expression of these cytokine/chemokines between air and hyperoxia groups at 48 h of exposure. IFN-interferon; MCP-monocyte chemoattractant protein; TNF-tumor necrosis factor.

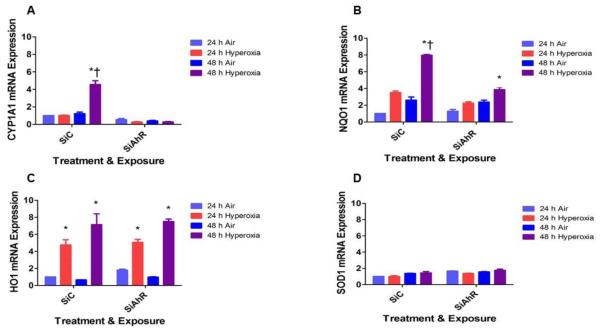

Hyperoxia-induced CYP1A1 and NQO1 mRNA expression is attenuated in AhR-deficient cells

AOE are known to attenuate hyperoxic injury by decreasing ROS levels. To determine whether the AOE play a role in the AhR-mediated effects on ROS generation, we analyzed the expression of CYP1A1, NQO1, HO1, and SOD1. Hyperoxia increased CYP1A1, NQO1, and HO1 mRNA expression compared to corresponding room air groups (Fig. 6). However, hyperoxia-induced CYP1A1 (Fig. 6A) and NQO1 (Fig. 6B) mRNA expression were significantly decreased in AhR- deficient cells compared to AhR-sufficient cells. There was no difference in hyperoxia-induced HO1 (Fig. 6C) mRNA expression between AhR-sufficient and –deficient cells. Hyperoxia failed to increase SOD1 (Fig. 6D) mRNA expression at the indicated time points in our in vitro model.

Figure 6. AhR deficiency decreases hyperoxia-induced CYP1A1 and NQO1 mRNA expression.

Control (SiC) or AhR (SiAhR) siRNA transfected HPMEC were exposed to air or hyperoxia for up to 48 h, following which RNA was extracted for real-time RT-PCR analyses of CYP1A1 (A), NQO1 (B), HO1 (C), and SOD1 (D) mRNA expression. Data are representative of at least three independent experiments. Values are presented as means ± SEM (n=3). Two-way ANOVA showed an effect of hyperoxia and AhR gene and an interaction between them for the dependent variables, CYP1A1 and NQO1, in this figure. Significant differences between air- and hyperoxia-exposed cells are indicated by *, p < 0.05. Significant differences between hyperoxia- exposed AhR-sufficient and –deficient cells are indicated by †, p < 0.05.

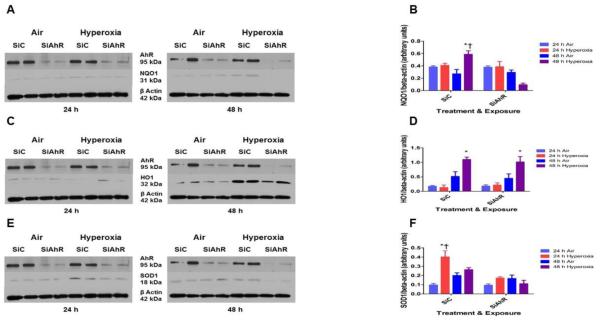

Hyperoxia-induced NQO1 and SOD1 protein expression is attenuated in AhR-deficient cells

Next, we determined whether hyperoxia and AhR regulates the expression of AOE at the protein level. Consistent with our real time RT-PCR analysis, hyperoxia increased NQO1 (Figs. 7A and B) and HO1 (Figs. 7C and D) protein expression. Furthermore, hyperoxia increased SOD1 (Figs. 7E and F) protein expression Interestingly, AhR-deficient cells had decreased SOD1 (Figs. 7E and F) and NQO1 (Figs. 7A and B) protein expression upon exposure to hyperoxia.

Figure 7. AhR deficiency decreases hyperoxia-induced NQO1 and SOD1 protein expression.

Control (SiC) or AhR (SiAhR) siRNA transfected HPMEC were exposed to air or hyperoxia for up to 48 h, following which cytoplasmic protein was extracted and western blotting was performed using anti-NQO1, HO1, SOD1, or β-actin antibodies. Representative western blots showing cytoplasmic NQO1 (A), HO1 (C), and SOD1 (E) protein expression. Densitometric analyses wherein NQO1 (B), HO1 (D), and SOD1 (F) band intensities were quantified and normalized to β-actin. Data are representative of at least three independent experiments. Values are presented as means ± SEM (n=3). Two-way ANOVA showed an effect of hyperoxia and AhR gene and an interaction between them for the dependent variables, NQO1 and SOD1, in this figure. Significant differences between air- and hyperoxia-exposed cells are indicated by *, p < 0.05. Significant differences between hyperoxia-exposed AhR-sufficient and –deficient cells are indicated by †, p < 0.05.

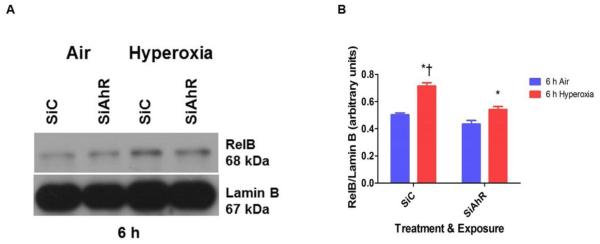

RelB activation is decreased in AhR-deficient HPMEC:

To ascertain whether the AhR interacts with NFκB to regulate hyperoxia-induced inflammation in our model, we analyzed nuclear p65 and RelB protein expression by western blotting. Interestingly, nuclear RelB (Figs. 8A and B) protein expression was significantly decreased in AhR-depleted cells upon exposure to hyperoxia. There was no difference in nuclear p65 protein expression between AhR-sufficient and –deficient cells upon exposure to hyperoxia (data not shown).

Figure 8. AhR deficiency decreases hyperoxia-induced nuclear RelB protein expression.

Control (SiC) or AhR (SiAhR) siRNA transfected HPMEC were exposed to air or hyperoxia for up to 6 h, following which nuclear protein was extracted and western blotting was performed using anti-AhR, RelB, or lamin B antibodies. (A) Representative western blot showing nuclear RelB protein expression. (B) Densitometric analyses wherein RelB band intensities were quantified and normalized to lamin B. Data are representative of at least three independent experiments. Values are presented as means ± SEM (n=3). Two-way ANOVA showed an effect of hyperoxia and AhR gene and an interaction between them for the dependent variable in this figure. Significant differences between air- and hyperoxia-exposed cells are indicated by *, p < 0.05. Significant differences between hyperoxia-exposed AhR-sufficient and –deficient cells are indicated by †, p < 0.05.

Discussion

The present study demonstrates that AhR deficiency increases the susceptibility of fetal HPMEC to hyperoxic injury via mechanism(s) entailing AOE and NF-κB signaling. In human fetal lung-derived HPMEC in vitro, deficient AhR-signaling mediated increase in hyperoxic injury correlated with decreased expression of AOE and decreased RelB activation.

To investigate the molecular mechanism(s) of hyperoxic lung injury, we used an in vitro model, wherein cell proliferation, viability, death, oxidative stress, and inflammation were determined in AhR-sufficient and –deficient HPMEC exposed to hyperoxia. The AhR is a versatile transcription factor that has important physiological functions in addition to its widely established role in the induction of a battery of genes involved in the metabolism of xenobiotics. Studies from our laboratory and others have reported that AhR may be a crucial regulator of oxidant stress and inflammation through the induction of several detoxifying enzymes or via “cross-talk” with other signal transduction pathways. In adult mice, we demonstrated that activation of AhR by omeprazole in adult mice (Shivanna et al., 2011b) and in the adult human lung-derived H441 cells (Shivanna et al., 2011a) attenuates hyperoxic injury. However, whether AhR regulates hyperoxic injury in primary human fetal lung cells has not been investigated. Therefore, we conducted experiments in human fetal lung derived HPMEC in vitro, both in the presence and absence of a functional AhR, to investigate whether AhR modulates hyperoxic injury.

Initially, we studied the interaction between hyperoxia and AhR. Functional activation of AhR results in its translocation into the nucleus, which causes transcriptional activation of the AhR gene battery that includes phase I and II detoxification enzymes such as CYP 1A1 and NQO1 (Fujisawa-Sehara et al., 1987; Rushmore et al., 1990; Favreau and Pickett, 1991; Whitlock, 1999). Therefore, we analyzed the expression of the nuclear AhR protein, and phase I and II enzymes to determine the functional activation of the AhR. Interestingly, we observed time- dependent increases in CYP1A1 and NQO1 expression in air-exposed cells (Figs. 1C-F). This could be due to the generation of endogenous AhR ligands in the cell culture media (Oberg et al., 2005). However, additional experiments are needed to support this idea. Our results suggest that hyperoxia in itself translocates the AhR into the nucleus (Figs. 1A and B) and transcriptionally activates the expression of CYP1A1 and NQO1. Although, hyperoxia increased CYP1A1 (Fig. 1C) and NQO1 (Fig. 1D) mRNA expression, and NQO1 (Figs. 1E and F) protein expression, it failed to upregulate CYP1A1 protein expression (data not shown). The discrepancies in our observations between CYP1A1 mRNA and protein expression suggest that hyperoxia regulates CYP1A1 via transcriptional rather than translational mechanisms in HPMEC, although the exact mechanisms are unknown at this time. Additionally, the molecular mechanisms by which hyperoxia activate pulmonary AhR also remain unknown at the present time.

Hyperoxia-induced expression of the phase I and II enzymes have been observed by several other investigators both in adult (Moorthy et al., 1997; Cho et al., 2002; Couroucli et al., 2002; Jiang et al., 2004) and newborn (McGrath-Morrow et al., 2009; Couroucli et al., 2011) rodents. This phenomenon might be a protective responsive to oxidative stress because of its striking resemblance to the effects of hyperoxia on the “classic” AOE such as superoxide dismutase, glutathione peroxidase, glutathione reductase, and catalase (Ho et al., 1996; Clerch, 2000). Furthermore, decreased expression of phase I and II enzymes in newborn AhRd mice compared to wild type mice was associated with increased hyperoxic lung injury in our previous study (Shivanna et al., 2013), which suggests that the effects of hyperoxia on these enzymes are a compensatory rather than a contributory response. In our study, there were no significant differences in expression of phase II enzymes between air-exposed AhR-sufficient and –deficient cells. These findings suggest that the constitutive expression of these enzymes might be equally regulated by other transcription factors such as Nrf2 in addition to the AhR. Additionally, this could be a cell specific effect since it is well known that the epithelial and endothelial cells respond differently to hyperoxia.

Next, we studied the effects of AhR on cytotoxicity, cell proliferation and death in HPMEC exposed to hyperoxia. Evidence suggests that exposure to hyperoxia results in increased generation of ROS (Budinger et al., 2002), and decreased cell proliferation (Ogunlesi et al., 2004; Yee et al., 2006) and viability (Bhakta et al., 2008). Although the mechanism(s) are unclear, increased ROS levels have been thought to contribute to acute and chronic lung disease in humans by inhibiting cell proliferation and increasing cell death by apoptosis or necrosis (Schoonen et al., 1990; De Paepe et al., 2005). Similarly, we observed increased ROS generation (Fig. 4), decreased cell viability (Fig. 3A) and proliferation (Fig. 3B), and increased late- apoptotic/necrotic cell death (Figs. 3C, D, and E) upon exposure to hyperoxia. However, these toxic effects of hyperoxia were significantly elevated in AhR-depleted cells, which supports the concept that AhR is a crucial regulator of oxidant-injury and that AhR mediates its effects in part by decreasing ROS generation. Importantly, studies have shown that in addition to ROS, inflammation plays a key role in the pathogenesis of hyperoxia-induced lung disorders such as BPD in preterm infants, and acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) in older children and adults (Barazzone and White, 2000; Saugstad, 2003; Davidson et al., 2013). Interestingly, in our model, AhR-deficiency was associated with a significant increase in MIP-1α (Fig. 5A) and MIP- 1β (Fig. 5B) levels both in air and hyperoxic conditions. MIP-1α and MIP-1β are chemokines that can activate granulocytes and initiate an inflammatory response. Several other investigators have suggested that MIP-1 chemokines may be an important mediator of hyperoxia-induced acute (Quintero et al., 2010) and chronic (Warner et al., 1998; Nold et al., 2013) lung injury in mice. Thus, our result in human cells signify the beneficial anti-inflammatory role of the AhR in hyperoxia-induced lung disorders in humans. Although, we did not notice significant differences in other cytokines and chemokines that are associated with BPD and ARDS, it is possible that we might have missed the time period wherein these cytokines and chemokines levels may have been elevated.

The molecular mechanism(s) by which the pulmonary AhR protects against hyperoxic lung injury remains poorly defined. Interestingly, we observed significant upregulation of pulmonary CYP1A1, NQO1, and SOD1 enzymes (Figs. 6 and 7) in AhR-sufficient compared to AhR- deficient cells upon exposure to hyperoxia. This suggests that AhR increases the expression of these enzymes under hyperoxic conditions. Although, we did not notice significant differences in SOD1 mRNA (Fig 6D) expression between air- and hyperoxia-exposed cells, it is possible that we might have missed an earlier time period wherein the mRNA levels may have been elevated. The protective effects of CYP1A enzymes against hyperoxic lung injury in rodents have been extensively documented, as evidenced by 1) attenuation of hyperoxic lung injury in rodents treated with CYP1A inducers, β-napthoflavone or 3-methylcholanthrene (Mansour et al., 1988; Sinha et al., 2005; Moorthy, 2008; Couroucli et al., 2011); 2) potentiation of hyperoxic injury in rats treated with CYP1A inhibitor, 1-aminobenzotriazole (Moorthy et al., 2000); 3) increased susceptibility of rodents deficient in genes for AhR (Couroucli et al., 2002; Jiang et al., 2004) to hyperoxic lung injury. In addition, the AOE such as NQO1 and SOD1 have been shown to protect cells and tissues against oxidant injury induced by various toxic chemicals (O'Brien, 1991) and oxygen (Cho et al., 2002; Das et al., 2006; McGrath-Morrow et al., 2009; Zhang et al., 2014). The protective mechanisms of these enzymes have been attributed to their ability to conjugate and scavenge the reactive electrophiles and lipid peroxidation products generated by an oxidant injury (Cho et al., 2002; Zhang et al., 2014). AhR-mediated protection against hyperoxia-induced toxicity may be attributed at least in part to these enzymes. It is important to note that AhR activation results in the induction of several detoxifying enzymes, which may be collectively more effective against an oxidant injury compared to the induction of a single enzyme.

NF-κB pathway is known to modulate hyperoxia-induced inflammation. NF-κB signaling is mediated via canonical and noncanonical (alternative) pathways, the former mainly comprising of RelA (p65) and p50 and the latter involving RelB and p52 (Bonizzi and Karin, 2004). Although, the canonical pathway is associated with an inflammatory state, the alternative or non- canonical pathway is shown to inhibit inflammation (Weih et al., 1995; Hayden and Ghosh, 2004). Deficiency of RelB, a key component of the alternative NF-κB pathway, is associated with increased inflammatory mediators that includes MIP-1α and MIP-1β upon exposure to various inflammatory stimuli (Weih et al., 1995; Xia et al., 1997; Martucci et al., 2007), and the converse is found to be true upon RelB overexpression (McMillan et al., 2011; McMillan et al., 2013; Spinelli et al., 2014; Zago et al., 2014), which suggests that RelB is an important negative regulator of inflammation. Interestingly, several recent studies (Thatcher et al., 2007; Baglole et al., 2008; de Souza et al., 2014) indicate that AhR decreases lung inflammation by modulating RelB expression. Although, the exact mechanism(s) by which RelB inhibits inflammation is unknown, studies indicate that RelB might negatively regulate the classical NF-κB (p65:p50) inflammatory pathway by a feedback control mechanism that involves its competition with p65 to sequester p50 in an inactive form (Xia et al., 1997; Marienfeld et al., 2003; Yoza et al., 2006; Thatcher et al., 2007). Even though the nuclear p65 expression did not differ between hyperoxia- exposed AhR-sufficient and –deficient cells in our study, it is plausible that decreased nuclear RelB expression in AhR-deficient cells leads to increased canonical p65:p50 dimer signaling due to lack of the negative feedback control as mentioned above. Thus, our finding of decreased nuclear RelB expression (Figs. 8A and B) in hyperoxia-exposed AhR-deficient cells indicates that the protective effects of the AhR might also be mediated in part by its interaction with NF- κB pathway to upregulate nuclear RelB expression under hyperoxic conditions.

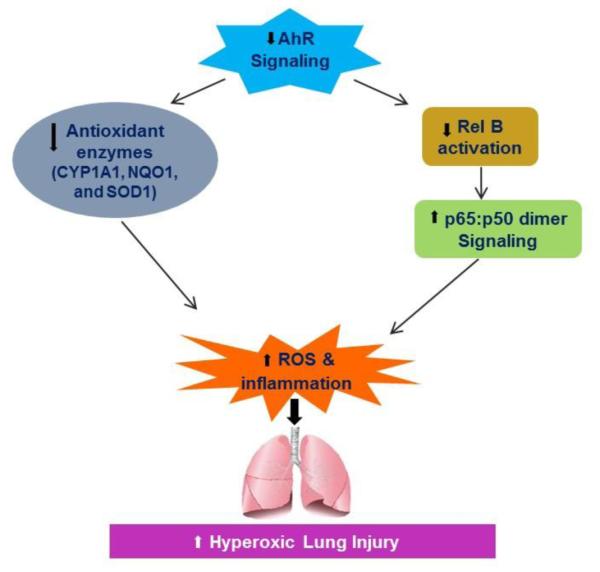

In summary, we demonstrate that deficient AhR signaling potentiates hyperoxia induced: (i) cytotoxicity (Fig. 3A); (ii) inhibition of cell proliferation (Fig. 3B); (iii) cell death (Figs. 3C, D, and E); (iv) ROS generation (Fig. 4); and (v) inflammation as indicated by MIP-1α (Fig. 5A) and MIP-1β (Fig. 5B) expression in HPMEC in vitro. Our data suggests that AhR signaling is required to decrease ROS generation and inflammation and protect fetal HPMEC against hyperoxic injury. We propose that the deficient AhR signaling increases hyperoxic injury via mechanisms entailing decreased AOE expression and decreased activation of the antiinflammatory NF-κB protein, RelB (Fig. 9). AhR can thus be a potential therapeutic target to improve current therapies of BPD in preterm infants and ARDS in older children and adults because activation of pulmonary AhR would target more than one pathway and mitigate both inflammation and oxidant stress, which are significant in the development of BPD and ARDS.

Figure 9. Proposed mechanism(s) by which AhR deficiency potentiates hyperoxic lung injury.

Deficient AhR signaling increases hyperoxia-induced ROS generation and inflammation, by decreasing the expression of antioxidant enzymes (AOE) and by modulating NF-κB activation via RelB. CYP1A1 - cytochrome P450 1A1; NQO1 – NADP(H) quinone oxidoreductase 1; SOD1 – superoxide dismutase 1.

Highlights.

AhR deficiency potentiates oxygen toxicity in human fetal lung cells.

Deficient AhR signaling increases hyperoxia-induced cell death.

AhR deficiency increases hyperoxia-induced ROS generation and inflammation.

Anti-oxidant enzyme levels are attenuated in AhR-deficient lung cells.

AhR-deficient lung cells have decreased Rel B activation.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grants from National Institutes of Health HD-073323 to B.S. and [ES-009132, HL-112516, HL-087174, and ES-019689] to B.M., American Heart Association BGIA20190008 to B.S., and by the Cytometry and Cell Sorting Core at Baylor College of Medicine with funding from the NIH (AI036211, CA125123, and RR024574) and the expert assistance of Joel M. Sederstrom. The study sponsors had no involvement in study design, data collection, analysis and interpretation, writing of the report or decision to submit the paper for publication.

Abbreviations

- AhR

aryl hydrocarbon receptor

- AOE

antioxidant enzymes

- ARDS

acute respiratory distress syndrome

- BPD

bronchopulmonary dysplasia

- CM-H2DCF-DA

5-(and-6)-chloromethyl-2’, 7’-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate

- CYP

cytochrome P450

- HO1

hemoxygenase 1

- HPMEC

human pulmonary microvascular endothelial cells

- MIP-1α

macrophage inflammatory protein-1 alpha

- MIP-1β

macrophage inflammatory protein-1 beta

- MTT

3-(4, 5-dimethylthiazolyl-2)-2, 5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide

- NF-κB

nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells

- NQO1

NADP(H) quinone oxidoreductase 1

- PARP

poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- SOD1

superoxide dismutase 1

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Bibliography

- Asikainen TM, White CW. Antioxidant defenses in the preterm lung: role for hypoxia-inducible factors in BPD? Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2005;203:177–188. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2004.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baglole CJ, Maggirwar SB, Gasiewicz TA, Thatcher TH, Phipps RP, Sime PJ. The aryl hydrocarbon receptor attenuates tobacco smoke-induced cyclooxygenase-2 and prostaglandin production in lung fibroblasts through regulation of the NF-kappaB family member RelB. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2008;283:28944–28957. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M800685200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barazzone C, White CW. Mechanisms of cell injury and death in hyperoxia: role of cytokines and Bcl-2 family proteins. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2000;22:517–519. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.22.5.f180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beischlag TV, Luis Morales J, Hollingshead BD, Perdew GH. The aryl hydrocarbon receptor complex and the control of gene expression. Crit Rev Eukaryot Gene Expr. 2008;18:207–250. doi: 10.1615/critreveukargeneexpr.v18.i3.20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhakta KY, Jiang W, Couroucli XI, Fazili IS, Muthiah K, Moorthy B. Regulation of cytochrome P4501A1 expression by hyperoxia in human lung cell lines: Implications for hyperoxic lung injury. Toxicology and applied pharmacology. 2008;233:169–178. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2008.08.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhandari V, Choo-Wing R, Lee CG, Zhu Z, Nedrelow JH, Chupp GL, Zhang X, Matthay MA, Ware LB, Homer RJ, Lee PJ, Geick A, de Fougerolles AR, Elias JA. Hyperoxia causes angiopoietin 2-mediated acute lung injury and necrotic cell death. Nat Med. 2006;12:1286–1293. doi: 10.1038/nm1494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonizzi G, Karin M. The two NF-kappaB activation pathways and their role in innate and adaptive immunity. Trends in immunology. 2004;25:280–288. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2004.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budinger GR, Tso M, McClintock DS, Dean DA, Sznajder JI, Chandel NS. Hyperoxia-induced apoptosis does not require mitochondrial reactive oxygen species and is regulated by Bcl-2 proteins. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:15654–15660. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109317200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burbach KM, Poland A, Bradfield CA. Cloning of the Ah-receptor cDNA reveals a distinctive ligand-activated transcription factor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992;89:8185–8189. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.17.8185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carver LA, Bradfield CA. Ligand-dependent interaction of the aryl hydrocarbon receptor with a novel immunophilin homolog in vivo. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:11452–11456. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.17.11452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho HY, Jedlicka AE, Reddy SP, Kensler TW, Yamamoto M, Zhang LY, Kleeberger SR. Role of NRF2 in protection against hyperoxic lung injury in mice. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2002;26:175–182. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.26.2.4501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clerch LB. Post-transcriptional regulation of lung antioxidant enzyme gene expression. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2000;899:103–111. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2000.tb06179.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Couroucli XI, Liang YH, Jiang W, Wang L, Barrios R, Yang P, Moorthy B. Prenatal administration of the cytochrome P4501A inducer, Beta-naphthoflavone (BNF), attenuates hyperoxic lung injury in newborn mice: implications for bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD) in premature infants. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2011;256:83–94. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2011.06.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Couroucli XI, Welty SE, Geske RS, Moorthy B. Regulation of pulmonary and hepatic cytochrome P4501A expression in the rat by hyperoxia: implications for hyperoxic lung injury. Mol Pharmacol. 2002;61:507–515. doi: 10.1124/mol.61.3.507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das A, Kole L, Wang L, Barrios R, Moorthy B, Jaiswal AK. BALT development and augmentation of hyperoxic lung injury in mice deficient in NQO1 and NQO2. Free Radic Biol Med. 2006;40:1843–1856. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2006.01.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson D, Zaytseva A, Miskolci V, Castro-Alcaraz S, Vancurova I, Patel H. Gene expression profile of endotoxin-stimulated leukocytes of the term new born: control of cytokine gene expression by interleukin-10. PloS one. 2013;8:e53641. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0053641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Paepe ME, Mao Q, Chao Y, Powell JL, Rubin LP, Sharma S. Hyperoxia-induced apoptosis and Fas/FasL expression in lung epithelial cells. American journal of physiology. Lung cellular and molecular physiology. 2005;289:L647–659. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00445.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Souza AR, Zago M, Eidelman DH, Hamid Q, Baglole CJ. Aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR) attenuation of subchronic cigarette smoke-induced pulmonary neutrophilia is associated with retention of nuclear RelB and suppression of intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1) Toxicological sciences : an official journal of the Society of Toxicology. 2014;140:204–223. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfu068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denis M, Cuthill S, Wikstrom AC, Poellinger L, Gustafsson JA. Association of the dioxin receptor with the Mr 90,000 heat shock protein: a structural kinship with the glucocorticoid receptor. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1988;155:801–807. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(88)80566-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emi Y, Ikushiro S, Iyanagi T. Xenobiotic responsive element-mediated transcriptional activation in the UDP-glucuronosyltransferase family 1 gene complex. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:3952–3958. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.7.3952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fanaroff AA, Stoll BJ, Wright LL, Carlo WA, Ehrenkranz RA, Stark AR, Bauer CR, Donovan EF, Korones SB, Laptook AR, Lemons JA, Oh W, Papile LA, Shankaran S, Stevenson DK, Tyson JE, Poole WK. Trends in neonatal morbidity and mortality for very low birthweight infants. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;196:147 e141–148. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2006.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Favreau LV, Pickett CB. Transcriptional regulation of the rat NAD(P)H:quinone reductase gene. Identification of regulatory elements controlling basal level expression and inducible expression by planar aromatic compounds and phenolic antioxidants. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:4556–4561. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujisawa-Sehara A, Sogawa K, Yamane M, Fujii-Kuriyama Y. Characterization of xenobiotic responsive elements upstream from the drug-metabolizing cytochrome P-450c gene: a similarity to glucocorticoid regulatory elements. Nucleic Acids Res. 1987;15:4179–4191. doi: 10.1093/nar/15.10.4179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayden MS, Ghosh S. Signaling to NF-kappaB. Genes & development. 2004;18:2195–2224. doi: 10.1101/gad.1228704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho YS, Dey MS, Crapo JD. Antioxidant enzyme expression in rat lungs during hyperoxia. Am J Physiol. 1996;270:L810–818. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1996.270.5.L810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hord NG, Perdew GH. Physicochemical and immunocytochemical analysis of the aryl hydrocarbon receptor nuclear translocator: characterization of two monoclonal antibodies to the aryl hydrocarbon receptor nuclear translocator. Molecular pharmacology. 1994;46:618–626. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang W, Welty SE, Couroucli XI, Barrios R, Kondraganti SR, Muthiah K, Yu L, Avery SE, Moorthy B. Disruption of the Ah receptor gene alters the susceptibility of mice to oxygen-mediated regulation of pulmonary and hepatic cytochromes P4501A expression and exacerbates hyperoxic lung injury. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2004;310:512–519. doi: 10.1124/jpet.103.059766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jobe AH, Hillman N, Polglase G, Kramer BW, Kallapur S, Pillow J. Injury and inflammation from resuscitation of the preterm infant. Neonatology. 2008;94:190–196. doi: 10.1159/000143721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mansour H, Levacher M, Azoulay-Dupuis E, Moreau J, Marquetty C, Gougerot-Pocidalo MA. Genetic differences in response to pulmonary cytochrome P-450 inducers and oxygen toxicity. J Appl Physiol. 1988;64:1376–1381. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1988.64.4.1376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marienfeld R, May MJ, Berberich I, Serfling E, Ghosh S, Neumann M. RelB forms transcriptionally inactive complexes with RelA/p65. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2003;278:19852–19860. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M301945200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martucci C, Franchi S, Lattuada D, Panerai AE, Sacerdote P. Differential involvement of RelB in morphine-induced modulation of chemotaxis, NO, and cytokine production in murine macrophages and lymphocytes. Journal of leukocyte biology. 2007;81:344–354. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0406237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGrath-Morrow S, Lauer T, Yee M, Neptune E, Podowski M, Thimmulappa RK, O'Reilly M, Biswal S. Nrf2 increases survival and attenuates alveolar growth inhibition in neonatal mice exposed to hyperoxia. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2009;296:L565–573. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.90487.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMillan DH, Baglole CJ, Thatcher TH, Maggirwar S, Sime PJ, Phipps RP. Lung-targeted overexpression of the NF-kappaB member RelB inhibits cigarette smoke-induced inflammation. The American journal of pathology. 2011;179:125–133. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2011.03.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMillan DH, Woeller CF, Thatcher TH, Spinelli SL, Maggirwar SB, Sime PJ, Phipps RP. Attenuation of inflammatory mediator production by the NF-kappaB member RelB is mediated by microRNA-146a in lung fibroblasts. American journal of physiology. Lung cellular and molecular physiology. 2013;304:L774–781. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00352.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moorthy B. Role in Drug Metabolism and Toxicity of Drugs and other Xenobiotics. RSC publishing; Cambridge: 2008. Cytochromes P450; pp. 97–135. C., I. [Google Scholar]

- Moorthy B, Nguyen UT, Gupta S, Stewart KD, Welty SE, Smith CV. Induction and decline of hepatic cytochromes P4501A1 and 1A2 in rats exposed to hyperoxia are not paralleled by changes in glutathione S-transferase-alpha. Toxicol Lett. 1997;90:67–75. doi: 10.1016/s0378-4274(96)03832-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moorthy B, Parker KM, Smith CV, Bend JR, Welty SE. Potentiation of oxygen-induced lung injury in rats by the mechanism-based cytochrome P-450 inhibitor, 1-aminobenzotriazole. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2000;292:553–560. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nold MF, Mangan NE, Rudloff I, Cho SX, Shariatian N, Samarasinghe TD, Skuza EM, Pedersen J, Veldman A, Berger PJ, Nold-Petry CA. Interleukin-1 receptor antagonist prevents murine bronchopulmonary dysplasia induced by perinatal inflammation and hyperoxia. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2013;110:14384–14389. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1306859110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Brien PJ. Molecular mechanisms of quinone cytotoxicity. Chem Biol Interact. 1991;80:1–41. doi: 10.1016/0009-2797(91)90029-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oberg M, Bergander L, Hakansson H, Rannug U, Rannug A. Identification of the tryptophan photoproduct 6-formylindolo[3,2-b]carbazole, in cell culture medium, as a factor that controls the background aryl hydrocarbon receptor activity. Toxicological sciences : an official journal of the Society of Toxicology. 2005;85:935–943. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfi154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogunlesi F, Cho C, McGrath-Morrow SA. The effect of glutamine on A549 cells exposed to moderate hyperoxia. Biochimica et biophysica acta. 2004;1688:112–120. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2003.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliver FJ, de la Rubia G, Rolli V, Ruiz-Ruiz MC, de Murcia G, Murcia JM. Importance of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase and its cleavage in apoptosis. Lesson from an uncleavable mutant. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1998;273:33533–33539. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.50.33533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollenz RS, Sattler CA, Poland A. The aryl hydrocarbon receptor and aryl hydrocarbon receptor nuclear translocator protein show distinct subcellular localizations in Hepa 1c1c7 cells by immunofluorescence microscopy. Molecular pharmacology. 1994;45:428–438. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quintero PA, Knolle MD, Cala LF, Zhuang Y, Owen CA. Matrix metalloproteinase-8 inactivates macrophage inflammatory protein-1 alpha to reduce acute lung inflammation and injury in mice. Journal of immunology. 2010;184:1575–1588. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0900290. (Baltimore, Md. : 1950) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rushmore TH, King RG, Paulson KE, Pickett CB. Regulation of glutathione S-transferase Ya subunit gene expression: identification of a unique xenobiotic-responsive element controlling inducible expression by planar aromatic compounds. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1990;87:3826–3830. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.10.3826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saugstad OD. Bronchopulmonary dysplasia-oxidative stress and antioxidants. Semin Neonatol. 2003;8:39–49. doi: 10.1016/s1084-2756(02)00194-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoonen WG, Wanamarta AH, van der Klei-van Moorsel JM, Jakobs C, Joenje H. Hyperoxia-induced clonogenic killing of HeLa cells associated with respiratory failure and selective inactivation of Krebs cycle enzymes. Mutation research. 1990;237:173–181. doi: 10.1016/0921-8734(90)90023-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shivanna B, Chu C, Welty SE, Jiang W, Wang L, Couroucli XI, Moorthy B. Omeprazole attenuates hyperoxic injury in H441 cells via the aryl hydrocarbon receptor. Free radical biology & medicine. 2011a;51:1910–1917. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2011.08.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shivanna B, Jiang W, Wang L, Couroucli X, Moorthy B. Omeprazole Attenuates Hyperoxic Lung Injury in Mice via Aryl hydrocarbon Receptor Activation, and is Associated with Increased Expression of Cytochrome P4501A Enzymes. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2011b doi: 10.1124/jpet.111.182980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shivanna B, Zhang W, Jiang W, Welty SE, Couroucli XI, Wang L, Moorthy B. Functional deficiency of aryl hydrocarbon receptor augments oxygen toxicity-induced alveolar simplification in newborn mice. Toxicology and applied pharmacology. 2013;267:209–217. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2013.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Short EJ, Klein NK, Lewis BA, Fulton S, Eisengart S, Kercsmar C, Baley J, Singer LT. Cognitive and academic consequences of bronchopulmonary dysplasia and very low birth weight: 8-year-old outcomes. Pediatrics. 2003;112:e359. doi: 10.1542/peds.112.5.e359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinha A, Muthiah K, Jiang W, Couroucli X, Barrios R, Moorthy B. Attenuation of hyperoxic lung injury by the CYP1A inducer beta-naphthoflavone. Toxicol Sci. 2005;87:204–212. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfi226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sogawa K, Fujii-Kuriyama Y. Ah receptor, a novel ligand-activated transcription factor. J Biochem. 1997;122:1075–1079. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a021864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spinelli SL, Xi X, McMillan DH, Woeller CF, Richardson ME, Cavet ME, Zhang JZ, Feldon SE, Phipps RP. Mapracorat, a selective glucocorticoid receptor agonist, upregulates RelB, an anti-inflammatory nuclear factor-kappaB protein, in human ocular cells. Experimental eye research. 2014;127:290–298. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2014.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thatcher TH, Maggirwar SB, Baglole CJ, Lakatos HF, Gasiewicz TA, Phipps RP, Sime PJ. Aryl hydrocarbon receptor-deficient mice develop heightened inflammatory responses to cigarette smoke and endotoxin associated with rapid loss of the nuclear factor-kappaB component RelB. The American journal of pathology. 2007;170:855–864. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2007.060391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thiel M, Chouker A, Ohta A, Jackson E, Caldwell C, Smith P, Lukashev D, Bittmann I, Sitkovsky MV. Oxygenation inhibits the physiological tissue-protecting mechanism and thereby exacerbates acute inflammatory lung injury. PLoS Biol. 2005;3:e174. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0030174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tirona RG, Kim RB. Nuclear receptors and drug disposition gene regulation. J Pharm Sci. 2005;94:1169–1186. doi: 10.1002/jps.20324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Marter LJ. Epidemiology of bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med. 2009;14:358–366. doi: 10.1016/j.siny.2009.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vina J, Vento M, Garcia-Sala F, Puertes IR, Gasco E, Sastre J, Asensi M, Pallardo FV. L-cysteine and glutathione metabolism are impaired in premature infants due to cystathionase deficiency. Am J Clin Nutr. 1995;61:1067–1069. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/61.4.1067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogel CF, Wu D, Goth SR, Baek J, Lollies A, Domhardt R, Grindel A, Pessah IN. Aryl hydrocarbon receptor signaling regulates NF-kappaB RelB activation during dendritic-cell differentiation. Immunology and cell biology. 2013;91:568–575. doi: 10.1038/icb.2013.43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warner BB, Stuart LA, Papes RA, Wispe JR. Functional and pathological effects of prolonged hyperoxia in neonatal mice. The American journal of physiology. 1998;275:L110–117. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1998.275.1.L110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weih F, Carrasco D, Durham SK, Barton DS, Rizzo CA, Ryseck RP, Lira SA, Bravo R. Multiorgan inflammation and hematopoietic abnormalities in mice with a targeted disruption of RelB, a member of the NF-kappa B/Rel family. Cell. 1995;80:331–340. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90416-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitlock JP., Jr. Induction of cytochrome P4501A1. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 1999;39:103–125. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.39.1.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright CJ, Agboke F, Chen F, La P, Yang G, Dennery PA. NO inhibits hyperoxia-induced NF-kappaB activation in neonatal pulmonary microvascular endothelial cells. Pediatric research. 2010;68:484–489. doi: 10.1203/PDR.0b013e3181f917b0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia Y, Pauza ME, Feng L, Lo D. RelB regulation of chemokine expression modulates local inflammation. The American journal of pathology. 1997;151:375–387. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yee M, Vitiello PF, Roper JM, Staversky RJ, Wright TW, McGrath-Morrow SA, Maniscalco WM, Finkelstein JN, O'Reilly MA. Type II epithelial cells are critical target for hyperoxia-mediated impairment of postnatal lung development. American journal of physiology. Lung cellular and molecular physiology. 2006;291:L1101–1111. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00126.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoza BK, Hu JY, Cousart SL, Forrest LM, McCall CE. Induction of RelB participates in endotoxin tolerance. Journal of immunology. 2006;177:4080–4085. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.6.4080. (Baltimore, Md. : 1950) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zago M, Rico de Souza A, Hecht E, Rousseau S, Hamid Q, Eidelman DH, Baglole CJ. The NF-kappaB family member RelB regulates microRNA miR-146a to suppress cigarette smoke-induced COX-2 protein expression in lung fibroblasts. Toxicology letters. 2014;226:107–116. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2014.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang B, Niu W, Xu D, Li Y, Liu M, Wang Y, Luo Y, Zhao P, Liu Y, Dong M, Sun R, Dong H, Li Z. Oxymatrine prevents hypoxia- and monocrotaline-induced pulmonary hypertension in rats. Free radical biology & medicine. 2014;69:198–207. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2014.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang N, Walker MK. Crosstalk between the aryl hydrocarbon receptor and hypoxia on the constitutive expression of cytochrome P4501A1 mRNA. Cardiovascular toxicology. 2007;7:282–290. doi: 10.1007/s12012-007-9007-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]