Abstract

Background

Socioeconomic transition is changing urban and rural communities in Sub-Saharan Africa. This study assessed stroke risk factors and associated characteristics in urban and rural Uganda.

Methods

We surveyed 5420 urban and rural participants and assessed stroke risk factor prevalence and socio-behavioural characteristics associated with risk factors.

Results

Rural participants were older with higher proportions of men and fewer poor compared to urban areas. Most prevalent modifiable stroke risk factors in all areas were hypertension (27.1% rural and 22.4% urban, P=0.004), overweight and obesity (22.0% rural and 42% urban P<0.0001), and elevated waist hip ratio (25.8% rural and 24.1% urban P=0.045). Diabetes, smoking, physical inactivity, harmful alcohol consumption were found in ≤5%. Age, family history of hypertension, and waist hip ratio were associated with hypertension in all while BMI, HIV were associated with hypertension only in urban dwellers. Sex and family history of hypertension were associated with BMI in all, while age and socio-economic status, diabetes were associated with BMI in urban dwellers only.

Conclusions

Stroke risk factors of diabetes, smoking, inactivity and harmful alcohol consumption are rare in Uganda. Rural dwellers tend to be older with hypertension and elevated waist hip ratio. Unlike high-income countries, higher socioeconomic status is associated with overweight and obesity.

Keywords: Risk factors, Rural, Urban, Stroke, Uganda

Introduction

Stroke is a leading cause of preventable death and disability in adults in many developing nations [1–7]. In Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) stroke occurs at much earlier ages resulting in a greater number of years of potential life lost [1, 2, 6, 7]. In developing countries, including Uganda, rapid western cultural adaptation like sedentary lifestyle, consumption of tobacco and alcohol, high fat/cholesterol diet as well as demographic transition are markedly increasing the burden of non-communicable diseases such as stroke [6, 8]. Deaths from non-communicable diseases are projected to increase by 17% over the next 10 years unless urgent action is taken [9].

Risk factors for stroke include hypertension, smoking, abdominal obesity, overweight and obesity, harmful alcohol consumption, physical inactivity, type 2 diabetes mellitus and hyperlipidemia [8, 10]. A large multicentre (INTERSTROKE) case control study showed that ten factors account for 90% of stroke risk and half of these are modifiable (hypertension, smoking, waist to hip ratio, diet, physical inactivity) [10]. Stroke risk factors once rare in traditional African societies are rapidly becoming a major public health problem [11, 12]. In some SSA countries major stroke risk factors have increased to epidemic proportions [13–15]. In Uganda, isolated studies reported that stroke risk factors are highly prevalent [16–24]. For example, hypertension occurs in 30.5% of adults in rural Western Uganda [21].

The high burden of stroke requires effective strategies for prevention, especially in resource limited settings [1, 25, 26] where there is large migration from rural to urban areas. However, effective stroke prevention needs to be informed by strategies targeting those at high risk for stroke [1, 27]. Characterization of most prevalent risk factors are often lacking in developing countries in Africa [1, 27].

This study assessed prevalence of stroke risk factors and the associated socio-behavioural and demographic characteristics between rural and urban populations in the most populous district in Uganda. Findings are expected to inform policy planning and may be generalizable to other SSA countries.

Methods

Study area and setting

Cross-sectional surveys were conducted between August 2012 and August 2013 in rural Busukuma sub-county and urban Nansana sub-county, Wakiso district, Uganda. Wakiso district population was estimated to be 1,310,100 in 2010 [28], making it the second most populous district in the country. Wakiso district surrounds the capital city Kampala, and is unique in that it has areas with markedly different levels of socio-economic development, ranging from peri-urban neighbourhoods (bordering the city and therefore undergoing rapid urbanisation) to typically rural areas. Most of the people understand or speak Luganda, a local Bantu dialect of the Baganda, the indigenous tribe of the region whose main occupation is subsistence farming. The district has seven health sub districts each with a level IV health centre. Multi-stage sampling was used to select the sub-counties of Wakiso district for survey implementation. First, the sub-counties were stratified into rural and urban and then one sub-county was chosen from each stratum by simple random sampling.

Enumeration and mapping

All households and other key features in the selected study areas were mapped and enumerated to generate a sampling frame for the survey. A household was defined as any single permanent or semi-permanent dwelling structure acting as the primary residence for a person or group of people. Household locations were mapped using hand-held global positioning system (GPS) receivers and readings were taken from the door of the household, if possible, or from a point that was most representative of the household.

Recruitment and enrolment

Prior to the survey day, mobilization teams that consisted of village health team members (VHT) visited the study villages in order to raise awareness of the study. The mobilization of study villages focused on engaging with participants at both a community and individual level, with the aim of achieving and maintaining high levels of participation. This process involved meeting local leaders with letters detailing the purpose and duration for the study.

Households were selected using a list randomly generated from the household enumeration database. Households were included if: 1) they had an adult aged 18 years or older, and 2) the selected adult was willing to provide written informed consent. Households were excluded if: 1) no adult resident was at home on more than 3 visits, or if the household was vacant.

In each household one adult (18 years or older) was selected to participate in the survey. Selected adults were briefed about the study in the appropriate language and asked to attend a centrally placed research clinic the following day.

Ethical approval

The survey protocol was approved by the Makerere University School of Medicine Research and Ethics Committee and The Uganda National Council of Science and Technology. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Study procedures

A modified expanded questionnaire based on the World Health Organisation (WHO) STEPs questionnaire [29] was administered. Information including demographic data, family history of hypertension and diabetes mellitus, and past and present medical history of stroke risk factors was collected. A physical examination including measurements of height, weight, waist circumference, hip circumference and blood pressure was conducted. Venous blood samples were collected to test for fasting lipid profiles, fasting blood sugar, rapid plasma reagin and HIV test.

Measurements

Questions on physical activity were derived from the STEPS tool, which adapts them from the WHO Global Physical Activity Questionnaire (GPAQ) [30]. The questions sought information on the participants’ undertaking of vigorous-intensity activities (e.g. digging, lifting heavy loads, construction work, etc.) and moderate –intensity activities (e.g. brisk walking, carrying light loads, riding a bicycle, recreational activities like physical exercises and walking during leisure, etc.). Time spent on these activities in a typical week was recorded. Participants were classified into those that met the WHO minimum recommendations for physical activity (at least 75 minutes of vigorous –intensity, or at least 150 minutes of moderate-intensity activities per week).

Alcohol use was assessed with questions on frequency, type of alcohol and quantity consumed. Participants classified as engaging in harmful alcohol consumption were men who had 5 or more or women who had 4 or more drinks on any day in a week in the one month preceding the survey [31, 32]. Study participants were requested beforehand to refrain from smoking and drinking alcohol or caffeinated beverages at least half an hour before the examination. Blood pressure was measured with an Omron automated sphygmomanometer model HEM 907 whose accuracy has been validated [33]. The participant was asked to sit on a chair and rest quietly for 15 minutes with his/her legs uncrossed. The left arm was then placed on a table with the palm facing upward and the ante-cubital fossa at the level of the lower sternum. Two arm cuffs that fitted arm circumferences 9–13 inches and 13–17 inches were used in the process. Three BP measurements were taken at least 5 minutes apart. The average of the last two readings was considered as the final BP reading. A participant was classified as being hypertensive if their average systolic BP was 140mmHg or higher, or if their diastolic BP was 90mmHg or higher, or if they were on antihypertensive treatment [34].

Data management and statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were carried out using Stata version 12.0 software (STATA Corporation, College Station, TX). The outcomes of interest were; hypertension defined as a systolic blood pressure >140 mmHg and/or a diastolic blood pressure of >90 mmHg or treatment with antihypertensive medication. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated as weight in kilograms divided by the square of height in meters. A participant was classified as overweight if the BMI was 25Kgm−2 or greater and obese if their BMI was 30Kgm−2 or greater [35]. Waist-hip ratio was abnormal if >0.90 for males and >0.85 for females [35].

The prevalence of known risk factors for stroke was summarized as percentages with ninety five percent binomial confidence intervals (CI). Univariable associations between hypertension and elevated BMI and their potential risk factors were assessed using logistic regression and all variables demonstrating an association at a 20% significance level were included into multivariable logistic regression models. Logical model building using both forward and backward elimination was used to generate minimum adequate models using a 5% significance level. Socioeconomic status and BMI were retained as fixed terms in the model assessing for factors associated with hypertension regardless of statistical significance because of their known association to hypertension. For the same reason, physical inactivity was retained as a fixed term in the model assessing for factors associated with overweight/obesity.

Results

Characteristics of the participants

Five thousand four hundred and eighty one participants were approached to participate. Sixty participants had missing BP, anthropometric and laboratory measurements and were excluded. Mean age of rural participants was higher than urban participants, at 40.1 (16.3) years and 32.7 (12.4) years respectively. There was a statistically significant difference in the distribution of sex, socioeconomic status, family history of hypertension, and family history of diabetes between the rural and urban settings (P<0.001). Table 1 summarizes participant characteristics.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the participants

| Variable | Urban n (%) |

Rural n (%) |

P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age group (Years) (n, %) | |||

| Teenager <20 | 224 (5.8) | 41 (2.9) | |

| Young adult (20–39) | 2,767 (71.1) | 766 (53.9) | |

| Middle aged adult (40–59) | 725 (18.6) | 402 (28.3) | <0.001 |

| Elderly/Aged (60–80) | 178 (4.6) | 211 (14.9) | |

| Mean (SD) age (years) | 32.7(12.4) | 40.1 (16.3) | |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 1,072 (27.5) | 555 (39.1) | <0.001 |

| Female | 2,822 (72.5) | 865 (60.9) | |

| Social economic status | |||

| Poorest | 1,262 (32.4) | 110 (7.7) | |

| Poor | 1,088 (27.9) | 197 (13.9) | |

| Less poor | 672 (17.3) | 693 (48.8) | <0.001 |

| Least poor | 872 (22.4) | 420 (29.6) | |

| Family history of hypertension (n, %) | |||

| No | 2,746 (70.7) | 1,110 (78.4) | <0.001 |

| Yes | 1,136(29.3) | 306 (21.6) | |

| Family history of diabetes | |||

| No | 3,461 (89.1) | 1,324 (93.5) | <0.001 |

| Yes | 422 (10.9) | 92 (6.5) | |

Prevalence of modifiable risk factors for stroke

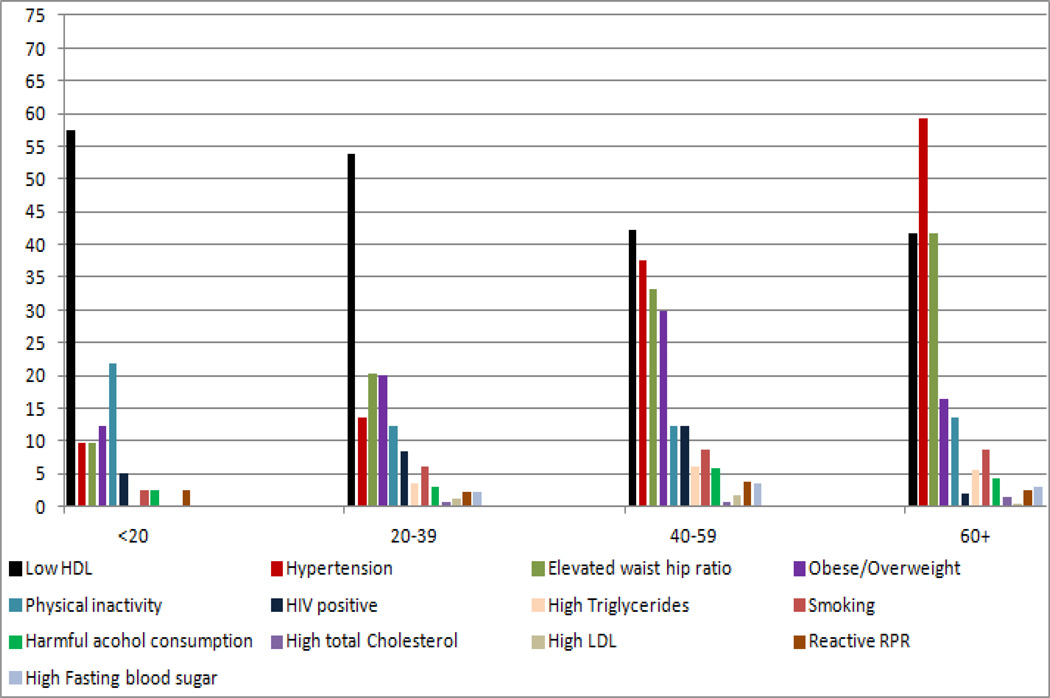

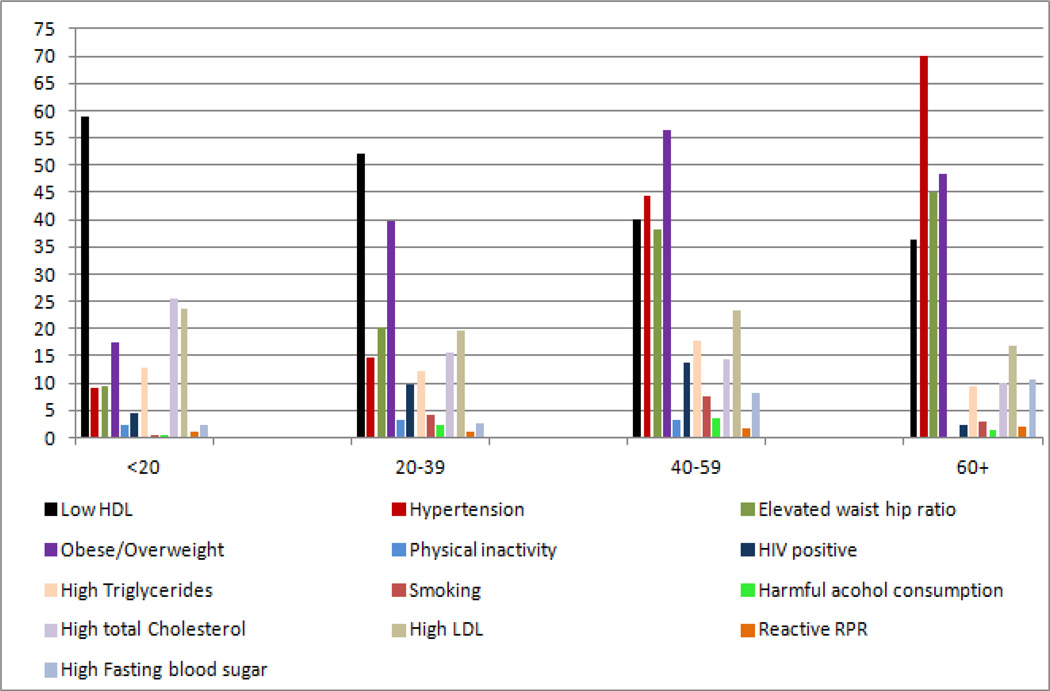

The most prevalent risk factors for stroke were hypertension (27.1% rural and 22.4% urban, P=0.004), overweight and obesity (22% rural and 42% urban, P<0.0001), and elevated waist to hip ratio (26.8% rural and 24.1% urban, P=0.045). Stroke risk factors of diabetes, smoking, physical inactivity and harmful alcohol consumption were found in < 5% in all populations. Stratifying by age, the highest prevalence of hypertension was among participants 60 years and older (59% in rural and 70% in urban). Similarly, the highest prevalence of elevated waist hip ratio was among participants 60 years and older (42% in rural and 45% in urban). Overweight/obesity was highest in participants aged 40–59 years (30% in rural and 56% in urban). Nearly half of all participants had low HDL cholesterol. High LDL cholesterol was highest (24%) among urban participants age < 20 years and highest (2%) among rural participants age 20–39 years. In contrast, physical inactivity was highest (22%) among urban participants age <20 years and highest (4%) among rural participants age 40–59 years. Figure 1 and Figure 2 summarize the prevalence of the modifiable stroke risk factors in rural and urban participants by age group.

Figure 1.

Prevalence of modifiable risk factors for stroke by age group in the rural setting.

HDL High density lipoprotein, LDL Low density lipoprotein, RPR Rapid plasma reagin

Figure 2.

Prevalence of modifiable risk factors for stroke by age group in the urban setting.

HDL high density lipoprotein, LDL low density lipoprotein, RPR rapid plasma reagin

Factors associated with being hypertensive

At multivariable logistic regression, non-modifiable factors associated with hypertension among rural and urban participants were being age 40–59 years (OR 3.74, 95% CI 1.3–10.9 and OR 6.06, 95% CI 3.6–10.2), respectively) and 60 years or older (OR 9.88, 95% CI 3.3–29.3 and OR 17.26, 95% CI 9.5–31.5), respectively) as well as family history of hypertension (OR 1.63, 95% CI 1.2–2.2 and OR 1.21, 95% CI 1.01–1.5), respectively).

Modifiable factors associated with hypertension among rural and urban residents were elevated waist hip ratio (OR 1.51, 95% CI 1.1–2.0 and OR 1.42, 95% CI 1.2–1.7), respectively), diabetes (OR 2.66, 95% CI 1.3–5.3 and OR 1.82, 95% CI 1.3–2.6), respectively). Harmful alcohol consumption (OR 1.77, 95% CI 1.1–2.9) and overweight and obesity (OR 1.53, 95% CI 1.3–1.8) were also associated with hypertension among the urban participants. Urban participants with HIV were less likely to be hypertensive (OR 0.40, 95% CI 0.3–0.6). Table 2 shows sociobehavioural and demographic characteristics associated with being hypertensive.

Table 2.

Factors associated with hypertension

| Variable | n/N | Rural AOR 95% CI |

P value | n/N | Urban AOR 95% CI |

P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age in years | ||||||

| <20 | 4/41 | 1 | 20/220 | 1 | ||

| 20–39 | 104/756 | 1.19 (0.4–3.4) | 0.746 | 396/2691 | 1.56 (0.9–2.6) | 0.084 |

| 40–59 | 147/392 | 3.74 (1.3–10.9) | 0.015 | 314/711 | 6.06 (4.1–10.9) | <0.001 |

| 60+ | 124/209 | 11.38 (3.3–29.3) | <0.001 | 121/173 | 17.26 (9.5–31.5) | <0.001 |

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 129/547 | 240/1036 | ||||

| Female | 250/851 | 611/2759 | ||||

| Social economic status | ||||||

| Poorest | 15/110 | 1 | 206/1237 | 1 | ||

| Poor | 26/195 | 0.72 (0.4–3.5) | 0.379 | 187/1061 | 1.01 (0.8–1.3) | 0.932 |

| Less poor | 196/681 | 1.17 (0.6–2.2) | 0.614 | 173/654 | 1.12 (0.9–1.5) | 0.393 |

| Least poor | 142/412 | 1.63 (0.9–3.0) | 0.126 | 285/843 | 1.22 (0.9–1.6) | 0.110 |

| Family history hypertension | ||||||

| No | 272/1,091 | 1 | 534/2683 | 1 | ||

| Yes | 107/303 | 1.63 (1.2–2.2) | 0.002 | 315/1102 | 1.21 (1.01–1.5) | 0.043 |

| Family history diabetes | ||||||

| No | 348/1,303 | 744/3375 | ||||

| Yes | 31/91 | 106/411 | ||||

| Current smoking | ||||||

| No | 350/1296 | 808/3622 | ||||

| Yes | 29/100 | 42/169 | ||||

| Harmful alcohol consumption | ||||||

| No | 361/1,340 | 821/3699 | 1 | |||

| Yes | 18/56 | 28/91 | 1.77 (1.1–2.9) | 0.029 | ||

| BMI | ||||||

| <25 | 272/1,090 | 1 | 374/2197 | 1 | ||

| >=25 | 107/308 | 1.33 (0.9–1.8) | 0.073 | 475/1591 | 1.53 (1.3–1.8) | <0.001 |

| Waist Hip Ratio | ||||||

| Normal | 231/1023 | 1 | 540/2879 | 1 | ||

| Elevated | 148/375 | 1.51 (1.1–2.0) | 0.005 | 311/915 | 1.42 (1.2–1.7) | 0.001 |

| Physical inactivity | ||||||

| No | 334/1217 | 1 | 826/3673 | 1 | ||

| Yes | 45/177 | 0.89 (0.6–1.3) | 0.579 | 23/110 | 1.07 (0.6–1.8) | 0.806 |

| Diabetes | ||||||

| No | 356/1354 | 1 | 770/3621 | 1 | ||

| Yes | 23/44 | 2.66 (1.3–5.3) | 0.005 | 81/173 | 1.82 (1.3–2.6) | 0.001 |

| HIV positive | ||||||

| No | 340/1231 | 773/3270 | 1 | |||

| Yes | 26/114 | 43/352 | 0.40 (0.3–0.6) | <0.001 | ||

| LDL cholesterol | ||||||

| Normal | 359/1330 | 645/2881 | ||||

| High | 7/15 | 168/739 | ||||

Age confounds social economic status in both rural and urban settings

Factors associated with overweight and obesity

At multivariable logistic regression, non-modifiable socio-demographic and behavioural characteristics associated with overweight and obesity among rural and urban participants was being female (OR 3.68, 95% CI 2.6–5.1 and OR 4.16, 95% CI 3.5–4.9), respectively). Increasing age (OR 5.87, 95% CI 3.9–8.9) and family history of diabetes (OR 1.38, 95% CI 1.1–1.8) were also independently associated with overweight and obesity in the urban setting.

As noted in Table 3, modifiable factors associated with overweight and obesity present only among urban dwellers included higher socio-economic status (OR 1.79, 95% CI 1.5–2.2), diabetes (OR 1.4, 95% CI 1.02–2.0) and high LDL cholesterol (OR 1.34, 95% CI 1.1–1.6).

Table 3.

Factors associated with overweight and obesity

| Variable | n/N | Rural AOR 95% CI |

P value | n/N | Urban AOR 95% CI |

P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age in years | ||||||

| <20 | 5/41 | 1 | 38/220 | 1 | ||

| 20–39 | 152/756 | 1.49 (0.6–3.9) | 0.429 | 1068/2685 | 3.46 (2.3–5.1) | <0.001 |

| 40–59 | 117/392 | 2.22 (0.8–6.0) | 0.117 | 402/711 | 5.87 (3.9–8.9) | <0.001 |

| 60+ | 34/209 | 0.99 (0.3–2.8) | 0.982 | 83/172 | 3.66 (2.2–6.1) | <0.001 |

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 51/547 | 1 | 206/1033 | 1 | ||

| Female | 257/851 | 3.68 (2.6–5.1) | <0.001 | 1385/2755 | 4.16 (3.5–4.9) | <0.001 |

| Social economic status | ||||||

| Poorest | 15/110 | 1 | 445/1234 | 1 | ||

| Poor | 33/195 | 1.21 (0.6–2.4) | 0.586 | 391/1058 | 1.12 (0.9–1.3) | 0.240 |

| Less poor | 164/681 | 1.57 (0.8–2.9) | 0.152 | 304/653 | 1.47 (1.2–1.8) | <0.001 |

| Least poor | 96/412 | 1.48 (0.8–2.8) | 0.228 | 451/843 | 1.79 (1.5–2.2) | <0.001 |

| Family history of hypertension | ||||||

| No | 217/1091 | 1 | 1031/2680 | 1 | ||

| Yes | 90/303 | 1.49 (1.1–2.0) | 0.010 | 556/1098 | 1.25 (1.1–1.5) | 0.007 |

| Family history of diabetes | ||||||

| No | 281/1303 | 1369/3365 | 1 | |||

| Yes | 26/91 | 222/410 | 1.38 (1.1–1.8) | 0.007 | ||

| Current smoking | ||||||

| No | 300/1296 | 1 | 1541/3615 | |||

| Yes | 7/100 | 0.46 (0.7–1.6) | 0.062 | 48/169 | ||

| Harmful alcohol consumption | ||||||

| No | 302/1340 | 1559/3692 | ||||

| Yes | 5/56 | 31/91 | ||||

| Physical inactivity | ||||||

| No | 269/1217 | 1 | 1550/3666 | 1 | ||

| Yes | 38/177 | 1.04 (0.7–1.6) | 0.839 | 35/110 | 0.71 (0.4–1.1) | 0.141 |

| Diabetes | ||||||

| No | 291/1354 | 1 | 1488/3614 | 1 | ||

| Yes | 17/44 | 1.88 (0.9–3.6) | 0.062 | 102/173 | 1.4 (1.02–2.0) | 0.039 |

| HIV positive | ||||||

| No | 271/1231 | 1379/3264 | ||||

| Yes | 27/114 | 141/352 | ||||

| LDL cholesterol | ||||||

| Normal | 359/1330 | 645/2881 | 1 | |||

| High | 7/15 | 168/739 | 1.34 (1.1–1.6) | 0.001 | ||

Discussion

In agreement with previous studies [10, 16, 22, 27, 36–40], hypertension, overweight and obesity, and elevated waist hip ratio were the most prevalent modifiable stroke risk factors in rural and urban Ugandans. Risk factors such as smoking, diabetes, physical inactivity and harmful alcohol intake, reported to be highly prevalent in other studies [10, 22] were rare.

In our sample, rural dwellers were older and had a higher proportion of the least poor, more men, more hypertension and more abdominal obesity compared to urban dwellers. Physical inactivity was more common in rural dwellers. It is possible that jobs and greater female economic opportunity attracts younger people and women to urban centers, leaving rural settings with higher concentrations of older people and men. Higher rates of hypertension and abdominal obesity in rural dwellers could reflect resident age and lack of access to information about healthy behaviors and stroke risk. Physically demanding employments such as forest and plantation/garden labour, and small-plot farming that requires traveling long distances to deliver produce or buy merchandise are very scarce today and may contribute to physical inactivity among rural residents.

Despite urban participants engaging in significantly more physical activity compared to the rural participants, there were higher rates of overweight and obesity as well as hyperlipidemia compared to rural participants. Among the 42% overweight and obese urban participants, 31.9% were aged 18 to 30 years. This is much higher than 14.6% reported in a study done in central Uganda 10 years ago [17] and suggests an increasing burden of overweight and obesity in urban communities. This supports the view that Uganda will have increasing burden of stroke as Western cultural adaptation and economic development among the urban population takes its toll [13]. In contrast to high-income countries where low socioeconomic status is associated with obesity [41], studies in Africa have demonstrated a strong positive relationship between obesity and high socioeconomic status [15, 42].

In this study the prevalence of low HDL cholesterol decreased with increasing age (40 years and older) which is unexpected given that there is an increase in prevalence of low HDL cholesterol with increasing age that is well documented from multiple studies [43, 44]. In addition to increasing age, the high prevalence of overweight/obesity, and hypertension in this group of participants should have favored an increase in prevalence of low HDL cholesterol with increasing age as reported from multiple studies [43, 44] but this was not the case. There are several genetic and environmental factors that influence HDL cholesterol [44]. For example, HIV decreases the levels of HDL cholesterol [45], physical conditioning has been shown to increase the levels of HDL cholesterol. Women have higher HDL concentration than men. Estrogen increases HDL cholesterol and protein and may in part account for the higher HDL in women [46]. Regarding genetics, age is an important modifier of phenotypes with resultant HDL cholesterol levels greater than in the younger counter parts [47]. While other investigators have identified various explanations that might explain demographic and clinical characteristics correlated with HDL, in our study the reason for the association is not clear. Additional studies conducted in Uganda and other sub-Saharan African settings are needed to see if this finding is replicated.

Non-modifiable factors associated with hypertension in our overall sample included older age and family history of hypertension. This is in agreement with previous studies [10, 38, 48, 49]. Also in agreement with other studies, modifiable factors associated with hypertension in our sample were overweight/obesity, elevated waist hip ratio, diabetes and harmful alcohol consumption [16, 27, 39, 40, 49]. Rural hypertension prevalence was higher than in urban settings despite rural participants being less overweight. Identification of both non-modifiable and modifiable factors associated with hypertension has important implications for targeted screening.

Interestingly, urban HIV positive participants were less likely to be hypertensive. Studies on blood pressure in HIV patients show conflicting results regarding the prevalence of hypertension [50–52]. Most health centres in urban Uganda provide comprehensive HIV/AIDs care [53]. It is possible that interventions emphasized in HIV care may offer protection against hypertension. In addition, HIV and HIV treatment may cause weight loss, thus reducing risk for hypertension.

Non-modifiable factors associated with being overweight and obese included age, sex, family history of hypertension and family history of diabetes in agreement with other studies. [16, 21, 54]. Similar findings were demonstrated in Uganda, Kenya and Morocco [16, 55, 56]. Sex as a factor associated with overweight and obesity is consistent with findings from other SSA settings [27, 39, 55, 57]. In contrast to our findings, estimates for most higher-income countries show that obesity is higher in men [58].

Modifiable factors associated with overweight and obesity which were seen only in the urban population included higher social economic status, diabetes and high LDL cholesterol. The increased likelihood of being overweight with urban upward social mobility might be ascribed to increased access to energy-dense foods and less strenuous jobs resulting into many people having a positive energy balance [9, 55]. In the early phases of nutritional transition, obesity is more frequent in wealthier individuals [39, 54, 55].

Conclusions

In this large general population sample in Uganda, hypertension, elevated waist hip ratio, overweight and obesity were the most prevalent stroke risk factors with significant differences in prevalence between rural and urban populations. Factors associated with the most prevalent risk factors differed between urban and rural populations. Stroke risk factors of diabetes, smoking, physical inactivity and harmful alcohol consumption were rare. Effective and pragmatic approaches in stroke prevention need to focus on those risk factors that are most relevant to a specific population. For rural residents in Central Uganda, approaches might preferentially target older individuals and men while emphasizing the “silent killer” aspect of hypertension as it relates to stroke. Among more affluent younger urban residents, dietary behavior and weight management may be particularly salient. Recognition of modifiable factors that can reduce rates of hypertension and obesity and implementation of strategies that lead to behavior change may eventually help stem the tide of increasing stroke burden in Uganda and in SSA more broadly.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all study participants in Nansana Town Council and Busukuma sub-county for their valuable time and information. The MEPI-CVD linked project coordinator Rhoda Namubiru, Mr. Joseph Sempa, the research team and research assistants are also duly acknowledged for the support, technical input, providing the equipment and assistance with carrying out the interviews respectively.

Funding acknowledgement

Research reported in this publication was supported by the Fogarty International Center, the National Heart Lung and Blood Institute, and the Common Fund of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number 5R24 TW008861. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the supporting offices.

Footnotes

Where work conducted: Makerere University College of Health Sciences

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

All authors made substantial contribution to conception and designing of the study and development of the data collection tools and data analysis. JN participated in data collection. All authors participated in drafting or revising the article critically for important intellectual content and approval of the final version to be published.

Contributor Information

Jane Nakibuuka, Department of Medicine, School of Medicine, Makerere University College of Health Sciences, P.O. Box 7051, Kampala, Uganda, Tel: +256772618111, Fax: +256041532591, nakibuukajm@yahoo.com.

Martha Sajatovic, Neurological and Behavioral Outcomes Center, University Hospitals Case Medical Center, Case Western Reserve University, School of Medicine, 11100 Euclid Avenue, Cleveland Ohio 44106, USA, Martha.sajatovic@uhhospitals.org.

Joaniter Nankabirwa, Department of Medicine, School of Medicine, Makerere University College of Health Sciences, P.O. Box 7051, Kampala, Uganda, jnankabirwa@yahoo.co.uk.

Anthony J Furlan, University Hospitals Case Medical Center, Neurological Institute Case Western Reserve University, School of Medicine, 11100 Euclid Avenue, Cleveland Ohio 44106, USA, Anthony.furlan@uhhospitals.org.

James Kayima, Department of Medicine, School of Medicine, Makerere University College of Health Sciences, P.O. Box 7051, Kampala, Uganda, jkkayima@gmail.com.

Edward Ddumba, Department of Medicine, St Raphael of St Francis Nsambya Hospital, Nkozi University, P.O. Box 7146, Kampala, Uganda, ddumbaentamuezala@gmail.com.

Elly Katabira, Department of Medicine, School of Medicine, Makerere University College of Health Sciences, P.O. Box 7051, Kampala, Uganda, Katabira@infocom.co.ug.

Jayne Byakika-Tusiime, Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, School of Public Health, Makerere University College of Health Sciences, P.O. Box 7072, Kampala, Uganda, tusjayne@hotmail.com.

References

- 1.Lemogoum D, Degaute JP, Bovet P. Stroke prevention, treatment, and rehabilitation in subsaharan Africa. Am J Prev Med. 2005;29:95–101. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2005.07.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Feigin VL, Forouzanfar MH, Krishnamurthi R, Mensah GA, Connor M, Bennett DA, Moran AE, Sacco RL, Anderson L, Truelsen T, O’Donnell M, Venketasubramanian N, Barker-Collo S, Lawes CM, Wang W, Shinohara Y, Witt E, Ezzati M, Naghavi M, Murray C. Global and regional burden of stroke during 1990–2010: findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. 2014;383:245–254. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(13)61953-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lozano R, Naghavi M, Foreman K, Lim S, Shibuya K, Aboyans V, Abraham J, Adair T, Aggarwal R, Ahn SY, Alvarado M, Anderson HR, Anderson LM, Andrews KG, Atkinson C, Baddour LM, Barker-Collo S, Bartels DH, Bell ML, Benjamin EJ, Bennett D, Bhalla K, Bikbov B, Bin Abdulhak A, Birbeck G, Blyth F, Bolliger I, Boufous S, Bucello C, Burch M, Burney P, Carapetis J, Chen H, Chou D, Chugh SS, Coffeng LE, Colan SD, Colquhoun S, Colson KE, Condon J, Connor MD, Cooper LT, Corriere M, Cortinovis M, de Vaccaro KC, Couser W, Cowie BC, et al. Global and regional mortality from 235 causes of death for 20 age groups in 1990 and 2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. 2012;380:2095–2128. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61728-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang H, Dwyer-Lindgren L, Lofgren KT, Rajaratnam JK, Marcus JR, Levin-Rector A, Levitz CE, Lopez AD, Murray CJ, et al. Age-specific and sex-specific mortality in 187 countries, 1970–2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. 2012;380:2071–2094. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61719-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Srindharan SE, Unnikrishnan JP, Sukumaran S, Sylaja PN, Nayak D, Sarma S, Radhakrishnan K. Incidence, types, risk factors and outcome of stroke in a developing country: the Trivadrum Stroke Registry. Stroke. 2007;40:1212–1218. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.531293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dalal PM, Bhattacharjee M. Stroke epidemic in India: hypertension-stroke control programme is urgently needed. J Assoc Physicians India. 2007;55:689–691. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Feigin VL, Lawes CM, Bennet DA, Anderson CS. Stroke epidemiology: a review of population-based studies of incidence, prevalence, and case-fatality in the late 20th century. Lancet Neurol. 2003;2:43–53. doi: 10.1016/s1474-4422(03)00266-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lim SS, Vos T, Flaxman AD, Danaei G, Shibuya K, Adair-Rohani H, Amann M, Anderson HR, Andrews KG, Aryee M, Atkinson C, Bacchus LJ, Bahalim AN, Balakrishnan K, Balmes J, Barker-Collo S, Baxter A, Bell ML, Blore JD, Blyth F, Bonner C, Borges G, Bourne R, Boussinesq M, Brauer M, Brooks P, Bruce NG, Brunekreef B, Bryan-Hancock C, Bucello C, Buchbinder R, Bull F, Burnett RT, Byers TE, Calabria B, Carapetis J, Carnahan E, et al. A comparative risk assessment of burden of disease and injury attributable to 67 risk factors and risk factor clusters in 21 regions, 1990–2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. 2012;380:2224–2260. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61766-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tunstall-Pedoe H Preventing Chronic Diseases. Vol. 35. Geneva: World Health Organization. International Journal of Epidemiology; 2006. A Vital Investment: WHO Global Report; pp. 1107–1107. [Google Scholar]

- 10.O'Donnell MJ, Xavier D, Liu L, Zhang H, Lim Chin S, Rao-Melacini P, Rangarajan S, Islam S, Pais P, Mc Queen MJ, Mondo C, Damasceno A, Lopez-Jaramillo P, Hankey GJ, Dans AL, Yusoff K, Truelsen T, Diener HC, Sacco RL, Ryglewicz D, Czlonkowska A, Weimar C, Wang X, Yusuf S. Risk factors for ischaemic and intracerebral haemorrhagic stroke in 22 countries (the INTERSTROKE study): a case-control study. Lancet. 2010;376:112–123. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60834-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Agyemang C. Rural and urban differences in blood pressure and hypertension in Ghana, West Africa. Public health. 2006;120:525–533. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2006.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.WHO. WHO STEPwise approach to chronic disease risk factor surveillance: STEPs country reports-African region. Available from: www.who.int/chp/steps/reports/en/

- 13.Thorogood M, Connor M, Tollman S, Lewando Hundt G, Fowkes G, Marsh J. A cross-sectional study of vascular risk factors in a rural South African population: data from the Southern African Stroke Prevention Initiative (SASPI) BMC Public Health. 2007;7:326. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-7-326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bosu W. Epidemic of hypertension in Ghana: a systematic review. BMC Public Health. 2010;10:418. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-10-418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fezeu L, Minkoulou E, Balkau B, Kengne AP, Awah P, Unwin N, Alberti GK, Mbanya JC. Association between socioeconomic status and adiposity in urban Cameroon. International Journal of Epidemiology. 2006;35:105–111. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyi214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mayega RW, Makumbi F, Rutebemberwa E, Peterson S, Ostenson CG, Tomson G, Guwatudde D. Modifiable socio-behavioural factors associated with overweight and hypertension among persons aged 35 to 60 years in eastern Uganda. PLoS One. 2012;7:47632. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0047632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Baalwa J, Byarugaba B, Kabagambe K, Otim A. Prevalence of overweight and obesity in young adults in Uganda. Afr Health Sci. 2010;10:367–373. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bimenya GS, Okot JK, Nangosa H, Anguma SA, Byarugaba W. Plasma cholesterol and related lipid levels of seemingly healthy public service employees in Kampala, Uganda. Afr Health Sci. 2006;6:139–144. doi: 10.5555/afhs.2006.6.3.139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lasky D, Becerra E, Boto W, Otim M, Ntambi J. Obesity and gender differences in the risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus in Uganda. Nutrition. 2002;18:417–421. doi: 10.1016/s0899-9007(01)00726-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Maher D, Waswa L, Baisley K, Karabarinde A, Unwin N, Grosskurth H. Epidemiology of hypertension in low-income countries: a cross-sectional population-based survey in rural Uganda. J Hypertens. 2011;29:1061–1068. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e3283466e90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wamala JF, Karyabakabo Z, Ndungutse D, Guwatudde D. Prevalence factors associated with hypertension in Rukungiri district, Uganda-a community-based study. Afr Health Sci. 2009;9:153–160. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mondo C. The prevalence and distribution of non-communicable diseases and their risk factors in Kasese district, Uganda. Uganda Medical Journal. 2012;1:10–16. doi: 10.5830/CVJA-2012-081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mpabulungi L, Muula AS. Tobacco use among high shool students in Kampala, Uganda: questionnaire study. Croat Med J. 2004;45:80–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Muula AS, Mpabulungi L. Cigarette smoking prevalence among school-going adolescents in two African capital cities: Kampala Uganda and Lilongwe Malawi. Afr Health Sci. 2007;7:45–49. doi: 10.5555/afhs.2007.7.1.45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Feigin VL, Lawes CM, Bennett DA, Barker-Collo S, Suzanne L, Parag V. Worldwide stroke incidence and early case fatality reported in 56 population-based studies: a systematic review. Lancet Neurol. 2009;8:355–369. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(09)70025-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.O'Donnell M, Yusuf S. Tackling the global burden of stroke: the need for large-scale international studies. Lancet Neurol. 2009;8:306–307. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(09)70024-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Maher D, Waswa L, Baisley K, Karabarinde A, Unwin N. Distribution of hyperglycaemia and related cardiovascular disease risk factors in low-income countries: a cross-sectional population-based survey in rural Uganda. Int J Epidemiol. 2011;40:160–171. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyq156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Uganda Bureau of Statistics (UBOS) Projections of demographic trends in Uganda 1. [Accessed 20 Sept 2013];2011 Available : www.ugandaonline.net/uganda_bureau_of_statistics. [Google Scholar]

- 29.World Health Organization; 2005. WHO STEPS stroke manual: the WHO STEPwise approach to stroke surveillance/Noncommunicable Diseases and Mental Health. [Google Scholar]

- 30.WHO. Global recommendations on physical activity for health. 2010 [PubMed]

- 31.WHO. International guide for monitoring alcohol consumption and related harm. Department of mental health and substance dependence noncommunicable diseases and mental health cluster. 2000

- 32.WHO. WHO; 2011. WHO STEPS Manual, STEPS Instrument. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gurpreet K, Tee GH, Karuthan C. Evaluation of the accuracy of the Omron HEM-907 blood pressure device. Med J Malaysia. 2008;63:239–243. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.NICE. NICE clinical guideline 127 diagnosing hypertension. [Accessed 20 Sept 2011];2011 Available: www.nice.org.uk/guidance/CG127. [Google Scholar]

- 35.The European food information council. The basics: Obesity and overweight. [Accessed Sept 2011];2006 Available: http://www.eufic.org/article/en/expid/basics-obesity-overweight. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Musinguzi G, Nuwaha F. Prevalence, awareness and control of hypertension in Uganda. PloS one. 2013;8:62236. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0062236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pires JE, Sebastiano YV, Langa AJ. Hypertension in Northern Angola: prevalence, associated factors, awareness, treatment and control. BMC public health. 2013;13:90. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kayima J, Wanyenze RK, Katamba A, Leontsini E, Nuwaha F. Hypertension awareness, treatment and control in Africa: a systematic review. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2013;13:1–11. doi: 10.1186/1471-2261-13-54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sodjinou R, Agueh V, Fayomi B, Delisle H. Obesity and cardio-metabolic risk factors in urban adults of Benin: relationship with socio-economic status, urbanisation, and lifestyle patterns. BMC Public Health. 2008;8:84. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-8-84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kamadjeu RM, Edwards R, Atanga JS, Kiawi EC, Unwin N. Anthropometry measures and prevalence of obesity in the urban adult population of Cameroon: an update from the Cameroon Burden of Diabetes Baseline Survey. BMC public health. 2006;6:228. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-6-228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sundquist K, Malmström M, Johansson S. Neighbourhood deprivation and incidence of coronary heart disease: a multilevel study of 2.6 million women and men in Sweden. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. 2004;58:71–77. doi: 10.1136/jech.58.1.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Christensen DL, Eis J, Hansen AW, Larsson MW, Mwaniki DL, Kilonzo B, Tetens I, Boit MK, Kaduka L, Borch-Johnsen K. Obesity and regional fat distribution in Kenyan populations: impact of ethnicity and urbanization. Annals of human biology. 2008;35:232–249. doi: 10.1080/03014460801949870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Brown CD, Higgins M, Donato KA, Rohde FC, Garrison R, Obarzanek E, Ernst ND, Horan M. Body Mass Index and the Prevalence of Hypertension and Dyslipidemia. Obesity Research. 2000;8:605–619. doi: 10.1038/oby.2000.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Aguilar-Salinas CA, Olaiz G, Valles V, Torres JM, Pérez FJ, Rull JA, Rojas R, Franco A, Sepulveda J. High prevalence of low HDL cholesterol concentrations and mixed hyperlipidemia in a Mexican nationwide survey. Journal of lipid research. 2001;42:1298–1307. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mashinya F, Alberts M, Colebunders R, Van Geertruyden J. Lipoprotein and its subclasses in HIV-infected individuals: a review. African journal for physical Health Education, Recreation and Dance. 2014;20:886–913. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Albers J, Warnick GR, Chenng M. Quantitation of high density lipoproteins. Lipids. 1978;13:926–932. doi: 10.1007/BF02533852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Clee SM, Kastelein JJ, Van Dam M, Marcil M, Roomp K, Zwarts KY, Collins JA, Roelants R, Tamasawa N, Stulc T, Suda T, Ceska R, Boucher B, Rondeau C, DeSouich C, Brooks- Wilson A, Molhuizen HO, Frohlich J, Genest JJr, Hayden MR. Age and residual cholesterol efflux affect HDL cholesterol levels and coronary artery disease in ABCA1 heterozygotes. The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2000;106:1263–1270. doi: 10.1172/JCI10727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lewington S, Clarke R, Oizilbash N, Peto R, Collins R. Age-specific relevance of usual blood pressure to vascular mortality: a meta-analysis of individual data for one million adults in 61 prospective studies. Lancet. 2002;360:1903–1913. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(02)11911-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wamala J, Karyabakabo Z, Ndungutse D, Guwatudde D. Prevalence factors associated with Hypertension in Rukungiri District, Uganda - A Community-Based Study. Afr Health Sci. 2009;9:153–160. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Khalsa A, Karim R, Mack WJ, Minkoff H, Cohen M, Yuong M, Anastos K, Tien P, Seaberg E, Levine A. Correlates of prevalent hypertension in a large cohort of HIV-infected women: Women's Interagency HIV Study. AIDS. 2007;21:2539–2541. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3282f15f7b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Arruda J, Roque de Lacerda E, Moura HR, Albuquerque LCRVA, Maria de Fatima PMMF, Filho DdBD, Albuquerque GTN, Gonclaves de Amaral VM, Ximenes JCZ, Alecar de Arraes M, Soares V. Risk factors related to hypertension among patients in a cohort living with HIV/AIDS. Brazilian Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2010;14:281–287. doi: 10.1590/s1413-86702010000300014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bergersen BM, Sandvik L, Dunlop O, Birkeland K, Bruun JN. Prevalence of hypertension in HIV-positive patients on highly active retroviral therapy (HAART) compared with HAART-naive and HIV-negative controls: results from a Norwegian study of 721 patients. European Journal of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases. 2003;22:731–736. doi: 10.1007/s10096-003-1034-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Scholten F, Mugisha J, Seeley J, Kinyanda E, Nakubukwa S, Kowal P, Naidoo N, Boerma T, Chatterji S, Grosskurth H. Health and functional status among older people with HIV/AIDS in Uganda. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:886. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Unwin N, James P, McLarty D, Machaybia H, Nkulila P, Tamin B, Nguluma M, McNally R. Rural to urban migration and changes in cardiovascular risk factors in Tanzania: a prospective cohort study. BMC Public Health. 2010;10:272. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-10-272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ziraba AK, Fotso JC, Ochako R. Overweight and obesity in urban Africa: A problem of the rich or the poor? BMC Public Health. 2009;9:465. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-9-465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Najdi A, El Achhab Y, Nejjari C, Norat T, Zidouh A, El Rhazi K. Correlates of physical activity in Morocco. Preventive medicine. 2011;52:355–357. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2011.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Martorell R, Khan LK, Hughes ML, Grummer-Strawn, Laurence M. Obesity in women from developing countries. European journal of clinical nutrition. 2000;54:247–252. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1600931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kelly T, Yang W, Chen CS, Reynolds K, He J. Global burden of obesity in 2005 and projections to 2030. International journal of obesity. 2008;32:1431–1437. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2008.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]