Abstract

Liver X receptors (LXRs) are determinants of hepatic stellate cell (HSC) activation and liver fibrosis. Freshly isolated HSCs from Lxrαβ−/− mice have increased lipid droplet (LD) size but the functional consequences of this are unknown. Our aim was to determine whether LXRs link cholesterol to retinoid storage in HSCs and how this impacts activation. Primary HSCs from Lxrαβ−/− and wild-type (WT) mice were profiled by gene array during in vitro activation. Lipid content was quantified by HPLC and mass spectroscopy. Primary HSCs were treated with nuclear receptor ligands, transfected with siRNA and plasmid constructs, and analyzed by immunocytochemistry. Lxrαβ−/− HSCs have increased cholesterol and retinyl esters (CEs & REs). The retinoid increase drives intrinsic retinoic acid receptor (RAR) signaling and activation occurs more rapidly in Lxrαβ−/− HSCs. We identify Rab18 as a novel retinoic acid responsive, lipid droplet associated protein that helps mediate stellate cell activation. Rab18 mRNA, protein, and membrane insertion increase during activation. Both Rab18 GTPase activity and isoprenylation are required for stellate cell lipid droplet loss and induction of activation markers. These phenomena are accelerated in the Lxrαβ−/− HSCs, where there is greater retinoic acid flux. Conversely, Rab18 knockdown retards lipid droplet loss in culture and blocks activation, just like the functional mutants. Rab18 is also induced with acute liver injury in vivo.

Conclusion

Retinoid and cholesterol metabolism are linked in stellate cells by the LD associated protein, Rab18. Retinoid overload helps explain the pro-fibrotic phenotype of Lxrαβ−/− mice and we establish a pivotal role for Rab18 GTPase activity and membrane insertion in wild-type stellate cell activation. Interference with Rab18 may have significant therapeutic benefit in ameliorating liver fibrosis.

Keywords: Liver fibrosis, Retinoic acid receptor, retinyl esters, cholesterol metabolism, stellate cell activation

INTRODUCTION

Liver fibrosis is a wound healing response characterized by deposition of fibrillar collagen and remodeling of extracellular matrix within the liver parenchyma by hepatic stellate cells (HSCs) (1, 2). In their ‘quiescent’ state, HSCs store the vast majority of the body’s retinoid (vitamin A) content in lipid droplets as REs (2, 3). During liver injury, HSCs ‘activate’ and up-regulate fibrotic, inflammatory, and proliferative pathways. HSC activation can be modeled in vitro by purifying cells and culturing them on plastic (2, 4). A phenotypic hallmark of HSC activation is the loss of retinoid containing LDs, but the function of retinoids in quiescent HSCs remains unknown (2, 3). It is also unclear whether retinoid loss is necessary for HSC activation. Deficiency in retinol esterification does not alter susceptibility to liver fibrosis (5), but retinoid overload leads to hepatic fibrosis and cirrhosis (6, 7).

We previously demonstrated an important role for ligand-activated LXRs in the biology of HSCs (8). LXRs govern whole body cholesterol homeostasis (9), and primary Lxrαβ−/− HSCs are pro-fibrotic and pro-inflammatory, with large LDs suggesting increased neutral lipid storage. We hypothesized the increased LD size might be from increased cellular cholesterol and find that Lxrαβ−/− HSCs have increased CE, but a surprisingly larger increase in RE, the storage form of vitamin A. This extra retinoid is metabolically important as RAR signaling is increased in Lxrαβ−/− HSCs. These cells lose their LDs more rapidly during in vitro activation and achieve the activated phenotype more quickly than WT cells. We identify the LD associated protein, Rab18, a small GTPase, as a key retinoid responsive mediator of this process. Rab18 is required for HSC activation, as knockdown of the protein, loss of its GTPase activity, or inhibition of its ability to insert into membranes blocks stellate cell activation. Conversely, increased expression in wild-type HSCs of either native Rab18 or Rab18 with a constitutively active GTPase accelerates activation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mouse models and primary stellate cell isolation

Six to seven month old male Lxrαβ−/− and WT mice on a pure C57/Bl6 background were used. Lxrαβ−/− mice were generated and characterized as previously described (8). Animals were housed on a 12 hour dark/light cycle with ad lib access to standard chow (LabDiet, PicoLab Rodent Diet 20) and water. Primary HSC isolation was carried out as previously detailed (8). Animal experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Research Advisory Committee of UCLA.

Microarray Analysis

Primary stellate cells isolated from WT and Lxrαβ−/− mice (n=12 mice per genotype) were cultured for 1, 2, 3, or 5 days on plastic. RNA from pooled samples was hybridized to Mouse Genome 430 2.0 Arrays (Affymetrix). See Supplementary Materials for details on the analysis.

Lipid Analysis and Mass Spectroscopy

Details of metabolite quantification can be found in the Supporting Materials and Methods. Cellular retinoids and sterols were measured as previously described with minor modifications (10, 11).

Real-Time Quantitative PCR

RNA was extracted using RNeasy (Qiagen) and reverse transcribed using iScript (Biorad). SYBR green master mix (Roche) was used to amplify targets on a Roche LightCycler. qRT-PCR results are determined by the ΔΔCt method and normalized to 36b4 gene expression. Primer sequences available upon request.

Statistics

All data are shown as mean ± SEM. Differences between two groups were compared with a 2-tailed unpaired t test. Differences between multiple groups were compared by 1-way ANOVA with post-hoc Tukey tests (GraphPad 4.0a). *, P < .05; **, P < .01; ***, P < .001; NS, P > .05. Comparator groups are indicated on each Figure.

Additional Methods

Please refer to the Supplementary Materials.

RESULTS

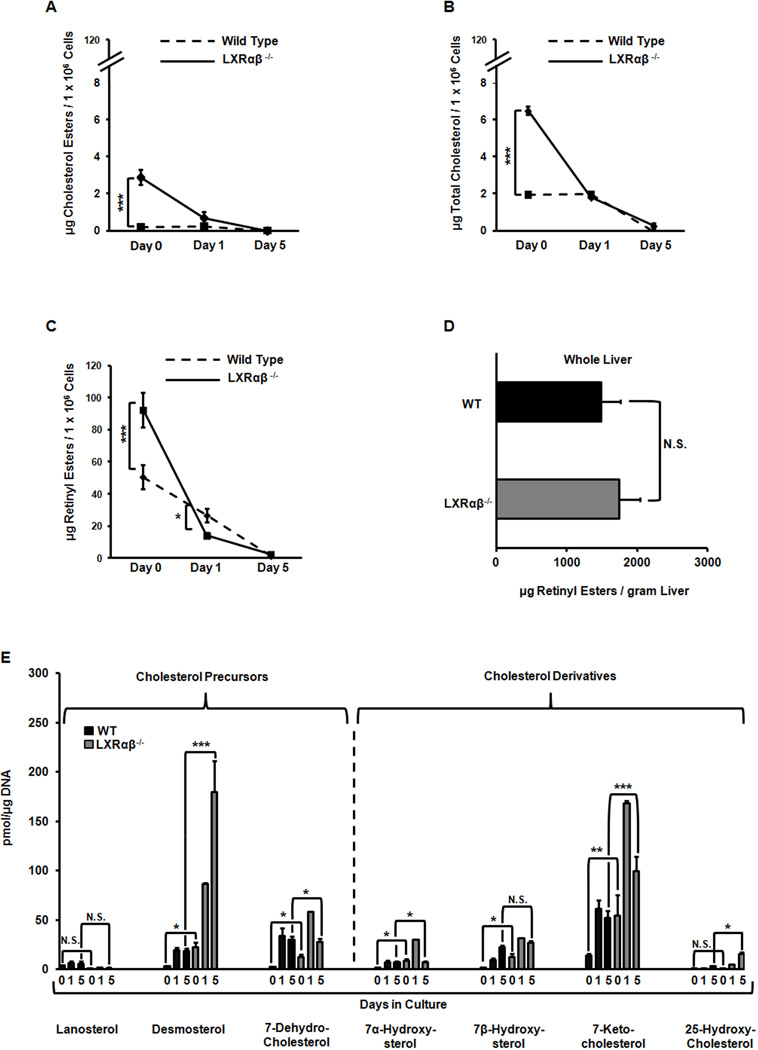

LXR null stellate cells have more intracellular cholesterol and retinoid storage

We used HPLC coupled with tandem mass spectroscopy (LC/MS) to quantify the lipid content of HSCs. Mice were fed a standard chow diet containing 15 IU/kg vitamin A. There were no differences in food consumption that could explain differences in hepatic retinoid storage (12). Freshly isolated Lxrαβ−/− HSCs have increased amounts of CE and cellular cholesterol (Fig. 1A–B). But the dominant lipid is retinyl ester (RE), in agreement with the literature (13), and these cells contain twice as much RE as WT cells (Fig. 1C). The rate of RE hydrolysis is also accelerated in Lxrαβ−/− HSCs, implying a marked difference in downstream retinoic acid signaling (Fig. 1C). Whole liver samples did not show a difference in RE content, suggesting RE distribution is preferentially increased in HSCs rather than hepatocytes (Fig. 1D). Cholesterol precursors and derivatives were significantly elevated in Lxrαβ−/− cells at isolation and during the course of activation (Fig. 1E). Taken together, these data indicate that Lxrαβ−/− HSCs store proportionately more retinyl esters than cholesterol esters and lose this retinoid more rapidly during activation.

Figure 1. LXR null hepatic stellate cells have increased retinyl ester stores and retinoic acid signaling.

Primary HSCs were isolated from WT and Lxrαβ−/− mice and cultured on plastic for 1–5 days. (A–C) Measurements of CEs, cellular cholesterol and REs; N=8–10 mice/genotype. (D) Measurements of REs from whole liver samples. N=5 mice/genotype. (E) LC/MS analysis of sterol species. N=8–10 mice/genotype. All data are mean ± SEM, analyzed on matched days by two-tailed t test (A–D) or 1-way ANOVA (E) with post-hoc tests: *, P < .05; **, P < .01; ***, P < .001; NS, P > .05.

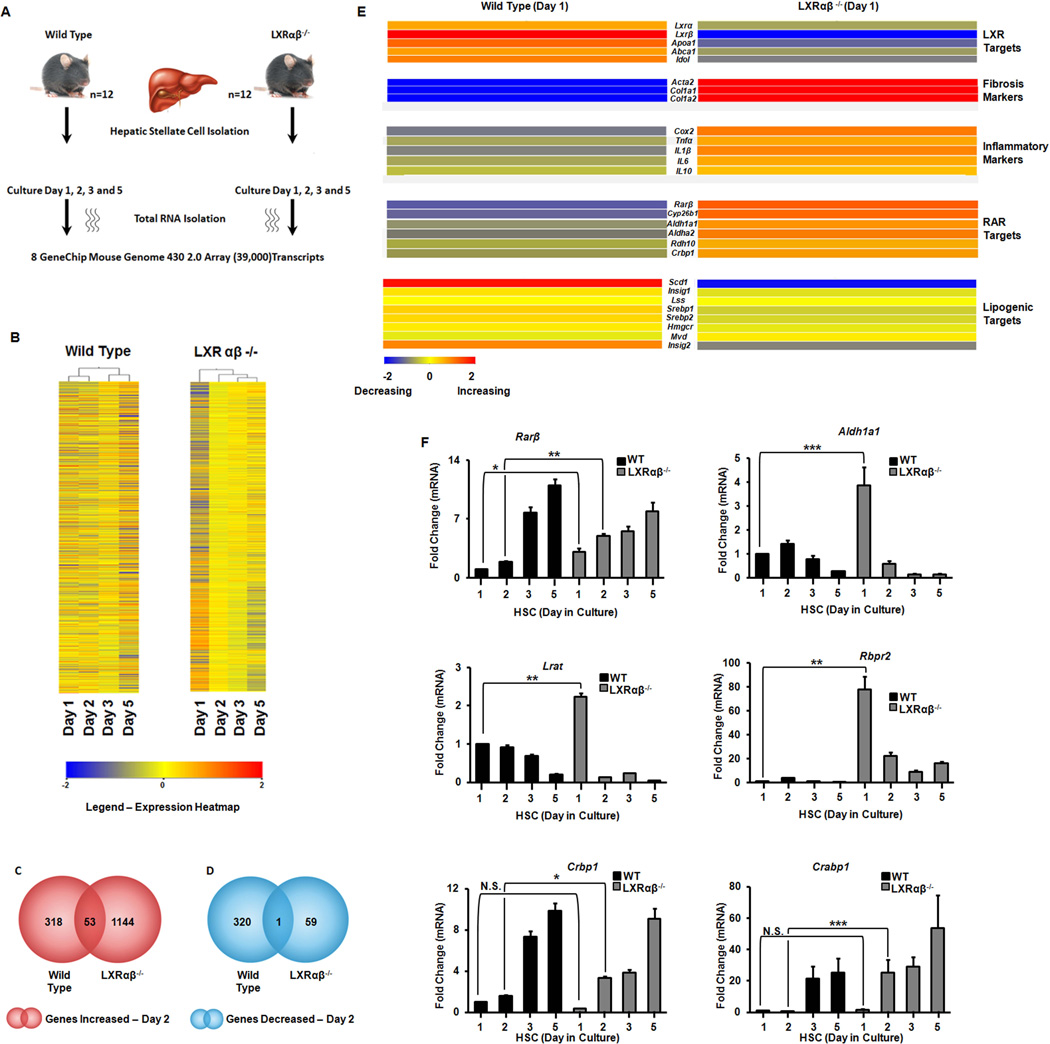

LXR null stellate cells have increased retinoic acid signaling

With an increased rate of retinyl ester hydrolysis we hypothesized that changes in gene expression drive the Lxrαβ−/− phenotype, which we analyzed with microarrays. Primary HSCs were purified and cultured on plastic (Fig. 2A). Hierarchical clustering shows remarkable differences in transcriptional profiles (Fig. 2B) with Lxrαβ−/− cells having more genes increasing in expression compared to the WT cells on day 2 (Fig. 2C–D). Intersectional analysis shows few common transcript changes in early activation but more targets in common when fully activated (Supp Fig. 1A). Gene ontologies (GOs) were clustered into functional subsets of biological functions and representative gene numbers (Supp Fig. 1B). Freshly isolated WT and Lxrαβ−/− HSCs do not differ in the basal expression of fibrotic (Acta2 or Col1a1) or RAR target genes (Supp Fig. 2A,B), thereby demonstrating that later differences in these programs (Figure 2E) are initiated as culture activation proceeds. Known LXR target genes were significantly decreased at baseline (e.g. lipogenic genes) and these cells express higher levels of inflammatory markers, as expected (Supp Fig. 2C,D) and previously published (8, 14).

Figure 2. Gene array analysis of activating hepatic stellate cells.

Primary HSCs from WT and Lxrαβ−/− mice (N=12 mice/genotype) were cultured on plastic. (A) Schematic of the work-flow. (B) Hierarchical clustering analysis of array data. K-means analysis is shown. (C–D) Total transcripts increasing (red) or decreasing (blue) by >2× difference. (E) Heat map of LXR, RAR, fibrotic, and inflammatory genes in primary HSCs after one day of culture activation. (F) Validation of RAR responsive genes by qRT-PCR from the array. Data are normalized to 36b4 expression and day 1 WT. Fold changes are mean ± SEM and differences between multiple groups compared by 1-way ANOVA with post-hoc tests: *, P < .05; **, P < .01; ***, P < .001.

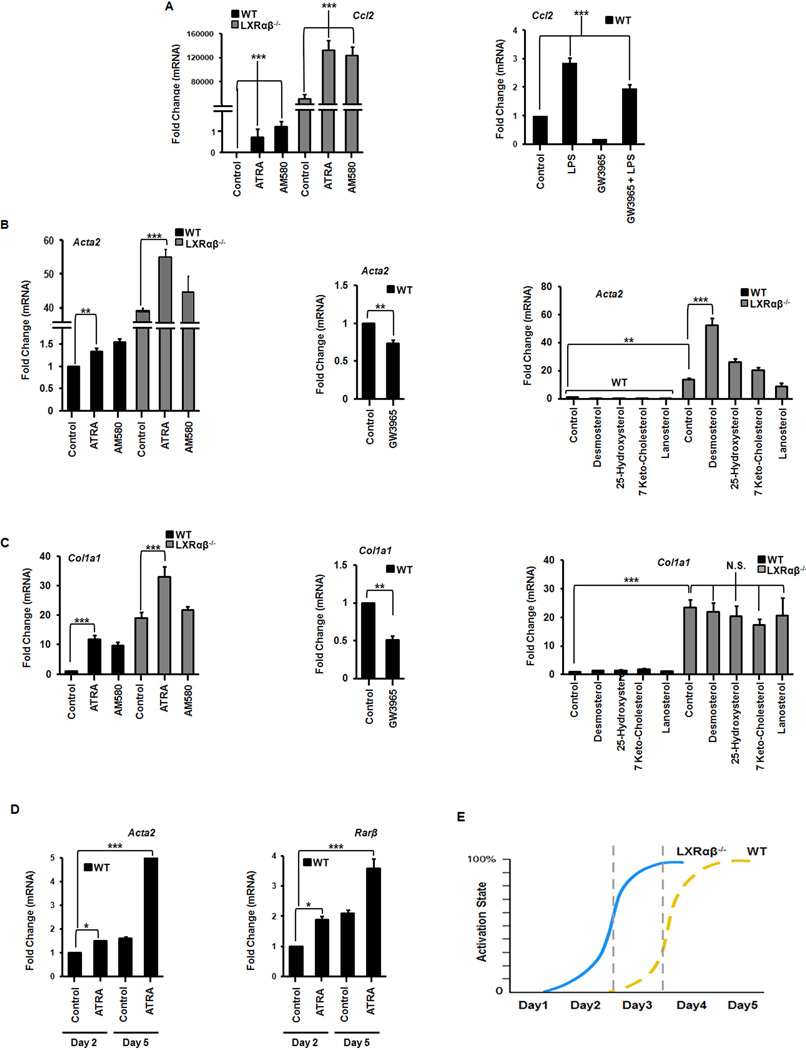

Microarray analysis and qRT-PCR confirm LXR signaling is abrogated in the knockout mouse and there are reciprocal early increases in fibrotic and inflammatory markers during culture activation (Fig. 2E, Supp Fig. 3). Interestingly, RAR target gene expression increases rapidly in Lxrαβ−/− HSCs (Fig. 2E,F) after retinyl esters stores diminish (Fig 1C). Genes responsible for retinoid storage are rapidly suppressed while those implicated in retinoid mobilization are increased (Fig. 2F). LXR signaling inhibits inflammatory gene expression (15), but whether RAR signaling can potentiate the fibrotic response of HSCs appears to be context dependent (6, 16, 17). RAR agonists (ATRA or AM580) induce inflammatory MCP-1 (Ccl2) while LXR agonists suppress it (Fig. 3A). RAR agonists also induce canonical fibrotic and RAR target genes in HSCs (Fig. 3B,C, Supp Fig. 4A–C). These genes are down regulated by the synthetic LXR agonist GW3965 but are mostly unresponsive to endogenous LXR ligands (Fig. 3B,C). At early points of culture activation WT HSCs are relatively refractory to retinoid stimulation compared to Lxrαβ−/− HSCs but gain responsiveness at later time points (Fig 3D). This supports a model whereby Lxrαβ−/− HSCs are temporally ‘frame shifted’ compared to WT HSCs (Fig 3E). ATRA induction of fibrotic and retinoic acid responsive genes are increased at later time points of activation in wild type cells (Fig. 3D). We also determined that Rarβ and Rarγ are the predominant RAR isotypes expressed in HSCs (Supp Fig. 4D), confirming findings from primary rat cells but in contrast to the reported observations in an immortalized stellate cell line (18, 19). Collectively, these data show that increased retinoid storage in Lxrαβ−/− HSCs leads to increased RAR signaling during activation.

Figure 3. Retinoic acid has a pro-inflammatory and pro-fibrotic effect on activating hepatic stellate cells.

Gene expression of inflammatory (A) and fibrotic (B–C) gene expression in HSCs on day 2 of culture activation exposed to LPS (1 ng/mL), ATRA (100 nM), AM580 (100 nM), GW3965 (1 µM), or indicated cholesterol intermediates (100 µg/mL). N=3–5 mice/genotype. (D) WT stellate cells become more responsive to ATRA, as measured by the expression of fibrotic and RAR target genes, as culture activation progresses (day 2 in culture versus day 5). (E) Lxrαβ−/− stellate cells are ‘frame shifted’ in regards to the timing of fibrotic gene expression. They do not express higher absolute levels of these genes, but reach maximal expression sooner than WT cells. All data are mean ± SEM, analyzed by 1-way ANOVA with post-hoc tests. *, P < .05; **, P < .01; ***, P < .001; NS, P > .05.

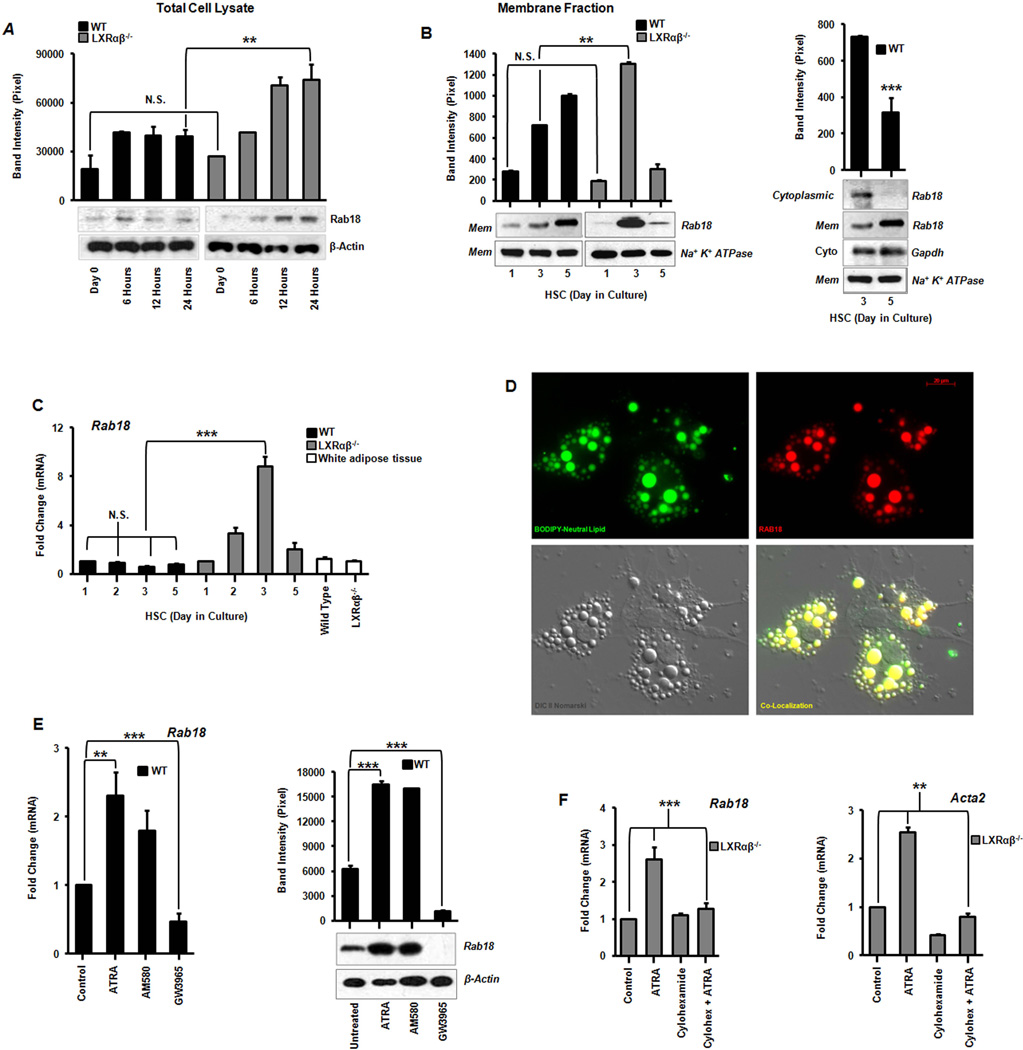

Rab18 is a retinoid responsive protein that inserts into lipid droplet membranes during stellate cell activation

To investigate how Lxrαβ−/− HSCs accommodate extra lipid, we examined genes thought to be involved in LD structure. Plin2 (Adrp) and Plin3 (Tip47) are well-expressed in stellate cells (Supp Fig. 5A). But only Plin3 shows marked transcriptional changes during stellate cell activation (Supp Fig. 5B). More Plin2 and Plin3 protein is found in Lxrαβ−/− membrane fractions in early activation (Supp Fig 5C), consistent with increased lipid storage in these cells. The dispersion of lipid droplets is reflected in the shift, especially of Plin3, to cytosolic fractions (Supp Fig. 5D).

Based on transcript and protein expression analyses, we identified one lipid droplet associated protein, Rab18, that increases during stellate cell activation. Rab18 is a small GTPase whose function in mammalian biology is still unclear (20). Western blotting of whole cell lysates shows an induction of Rab18 protein within the first 24 hours of primary stellate cell culture in both genotypes (Fig 4A). But membrane-bound levels (including those in LDs) rise sooner and to a greater total extent in Lxrαβ−/− HSCs compared to WT (Fig. 4B). In fact Rab18 protein shifts from the cytoplasmic to membrane fractions in WT cells without changes in mRNA (Fig 4B,C). This suggests that Rab18 is normally regulated by an LXR-dependent post-translational mechanism in WT cells. This layer of regulation is lost in Lxrαβ−/− HSCs where Rab18 is controlled directly by transcriptional mechanisms (Fig 4C). We found endogenous Rab18 protein co-localizes specifically with neutral lipid in stellate cells, such that virtually all of the membrane bound fraction of Rab18 is associated with lipid droplets (Fig. 4D & Supp Fig. 6).

Figure 4. Identification of Rab18, a retinoid responsive lipid droplet associated protein.

(A) Rab18 protein expression by immunoblotting from total cell lysates and corresponding band densitometry in the first 24 hours of primary stellate cell culture activation. (B) Immunoblot analysis of Rab18 in HSC membrane and cytosolic fractions showing a shift from cytoplasm to membrane inserted Rab18 as activation proceeds in wild type stellate cells. (C) Rab18 gene expression in culture activated primary HSCs and compared to white adipose tissue (N=12 mice/genotype). (D) Immunofluorescence microscopy demonstrates Rab18 localization to LD surfaces. BODIPY (green), Rab18 (red), Nomarski DIC imaging, and the merged image bottom right; magnification 63×. (E) Rab18 mRNA and protein expression in day 2 culture activated primary WT HSCs treated with ATRA (100 nM), AM580 (100 nM), or GW3965 (1 µM). (F) Cycloheximide (10 µM) abrogates ATRA-induced Rab18 expression. All data are mean ± SEM, analyzed by 1-way ANOVA with post-hoc tests: *, P < .05; **, P < .01; ***, P < .001; NS, P > .05.

We hypothesized that Rab18 could be influenced by increased cholesterol, retinoid, or inflammatory signaling in HSCs. We treated primary HSCs with sterols, LXR or RAR agonists, or an inflammatory stimulus (LPS). Rab18 levels are typically higher in Lxrαβ−/− HSCs, but largely unaffected by LPS or endogenous sterols (Supp Fig. 7A,B). But through specific RAR signaling, ATRA and Am580 induce Rab18 at both the mRNA and protein levels in WT cells while LXR agonist GW3965 suppresses it (Fig. 4E and Supp Fig. 7A). Cycloheximide blocks ATRA induction of Rab18 and the intermediate filament Acta2, suggesting that these genes are indirect RAR targets (Fig. 4F). Collectively, the data show Rab18 is a retinoid responsive protein that increases in lipid droplet membranes during stellate cell activation.

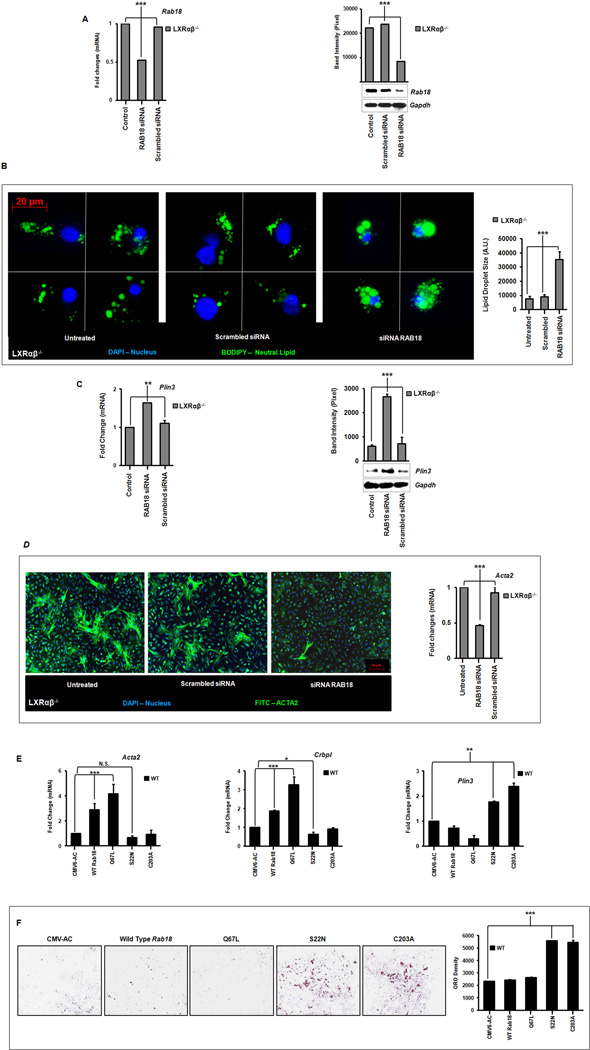

Rab18 knockdown, deletion of its GTPase activity, or prevention of its membrane insertion all inhibit stellate cell activation

We hypothesized that Rab18 insertion into membranes would have functional consequences for lipid droplet loss in stellate cells and that Rab18 knockdown would inhibit HSC activation in culture. We therefore transfected Lxrαβ−/− HSCs in early activation with a Rab18 siRNA and achieved a 50% knockdown of the mRNA and protein levels (Fig. 5A). These cells retain LDs for more than 72 hours in culture (Fig. 5B). The retained LDs contain large amounts of neutral lipid (Fig. 5B) and maintained a strong autofluorescent signal (data not shown), suggesting retention of REs. LD retention also correlated with higher levels of Plin3 expression which would be required for maintaining lipid droplet structure (Fig. 5C). Surprisingly, Rab18 knockdown also decreased actin protein and mRNA levels (Fig. 5D). These data show for the first time that LD loss during HSC activation is directly tied to the expression of α-smooth muscle actin. Rab18 interference specifically retards other activation markers such as Desmin ,Timp1, Timp2, Pdgfr and Mmp2, but does not directly affect inflammatory genes (Supp Fig. 8).

Figure 5. Rab18 knockdown retards lipid droplet loss and induction of α-smooth muscle actin.

Primary HSCs were transfected on day 2 of culture activation with a Rab18 siRNA or scrambled control. (A) Gene and protein expression from whole cell lysates following 24 hours of Rab18 knockdown. (B) Immunofluorescence microscopy shows retention of neutral LDs (BODIPY, green). Nuclei are blue (DAPI), magnification 63×. Quantitation of lipid droplet surface area using densitometry (36 cells represented) is shown at right. (C) Plin3 gene and protein expression after Rab18 knockdown. (D) Immunofluorescence microscopy of α-smooth muscle actin (anti-actin, green; nuclei, blue (DAPI); magnification 10×) and gene expression following Rab18 knockdown. (E) Gene expression of Acta2, Crbp1 and Plin3 following overexpression of native Rab18, GTPase (S22N – “off”; C67L – “on”), or isoprenylation (C203A) mutants. (F) Lipid retention in wild type stellate cells on day 5 of primary cell culture by Oil red O staining occurs when either Rab18 GTPase activity is quenched (S22N) or Rab 18 membrane insertion is abrogated (C203A). Quantification by total pixel counts is shown at right. N=3–5 mice/genotype. All data are mean ± SEM, analyzed by 1-way ANOVA with post-hoc tests: *, P < .05; **, P < .01; ***, P < .001; NS, P > .05.

To investigate whether Rab18 plays an important role in the activation of WT stellate cells we made plasmids expressing native Rab18 or mutations with a dominantly inactive ‘off’ GTPase (S22N), constitutively active ‘on’ GTPase (Q67L), or isoprenylation deficiency such that Rab18 cannot be inserted into lipid membranes (C203A). In primary WT stellate cells, overexpressing Rab18 S22N or Rab18 C203A suppressed activation markers (Acta2, Col1a1) and the intracellular retinol trafficking protein Crbp1 to below basal levels (Fig 5E). These mutants also increased levels of Plin3 (Fig 5E). Overexpressing native Rab18 has the opposite effect, and importantly, the Rab18 Q67L mutant shows further gain-of-function over native Rab18 (Fig 5E). These mutants also demonstrate marked phenotypic effects as the Rab18 S22N and Rab18 C203A mutants lead to marked retention of neutral lipid up to five days in primary culture (Fig 5F), a time point when WT cells have normally lost all their lipid content. In these experiments, equivalent levels of transfected constructs were achieved (Supp Fig 7C). These data collectively demonstrate that Rab18, with its GTPase and capacity for isoprenylation is a critical mediator of lipid droplet loss in stellate cells and acquisition of the fibroblastic phenotype.

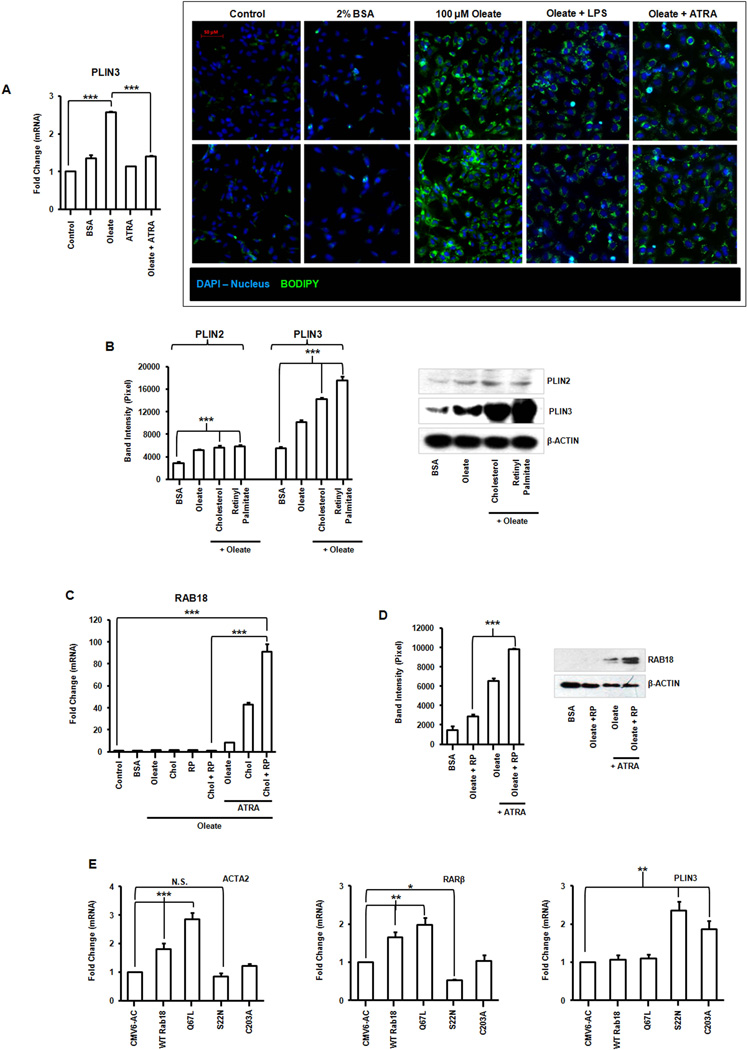

Regulation of RAB18 in immortalized human hepatic stellate cells

To determine whether RAB18 has a role in lipid droplet regulation in human HSCs, we lipid loaded LX-2 cells as previously described (21). These cells have an increase in the number of lipid droplets as shown by neutral lipid BODIPY staining and this lipid is lost by stimulation with ATRA or LPS (Fig. 6A). There is an increase in PLIN2 and PLIN3 as the LX-2 cells developed mature LDs (Fig. 6B), as expected (22). Perilipin expression also increases with the addition of larger amounts of lipid (Fig. 6B). We used the same ratio of REs to CEs found in primary murine stellate cells to co-load LX-2 cells (REs 50.6 µg/1×106 cells; CEs 0.2 µg /1×106 cells; Fig. 1A,C). In the presence of cholesterol and retinyl palmitate (RP) there is no increase in RAB18 unless the cells are also exposed to ATRA (Fig. 6C). Notably, loading with RP, and not oleate alone, robustly induces RAB18 protein (Fig. 6D). These data indicate that human HSCs, even activated ones, retain a memory of their LD storage phenotype and can distinguish between lipids (RE, CE, or oleate) when re-loaded. These data also show that RAB18 is ATRA-responsive in human cells. Overexpressing native human RAB18 or its GTPase and isoprenylation mutants in LX-2 cells has the same transcriptional effects on fibrotic markers, retinoid signaling, and lipid droplet structure that we saw in WT primary murine cells (Fig. 6E).

Figure 6. Regulation of RAB18 in an immortalized human stellate cell line.

(A) PLIN3 gene expression and fluorescence microscopy of neutral lipid storage (BODIPY, green) in LX-2 cells, oleate-loaded and treated with LPS (1 ng/mL) or ATRA (100 nM). Magnification 200×. (B) PLIN2 and PLIN3 protein expression in LX-2 cells reloaded with combinations of oleate (100 µM), cholesterol (0.2 µg) or retinyl palmitate (RP) (50.6 µg)). (C) Gene expression of RAB18 in lipid loaded LX-2s treated with ATRA (100 nM). (D) Protein expression of RAB18 in lipid loaded cells treated with or without ATRA. Changes quantified by densitometry. (E) Overexpression of RAB18 mutants (S22N, Q67L, C203A) in LX-2 cells coordinately alters expression of fibrotic (ACTA2), retinoid (RARβ) and lipid droplet (PLIN3) genes. All data are mean ± SEM, analyzed by 1-way ANOVA with post-hoc tests: *, P < .05; **, P < .01; ***, P < .001; NS, P > .05.

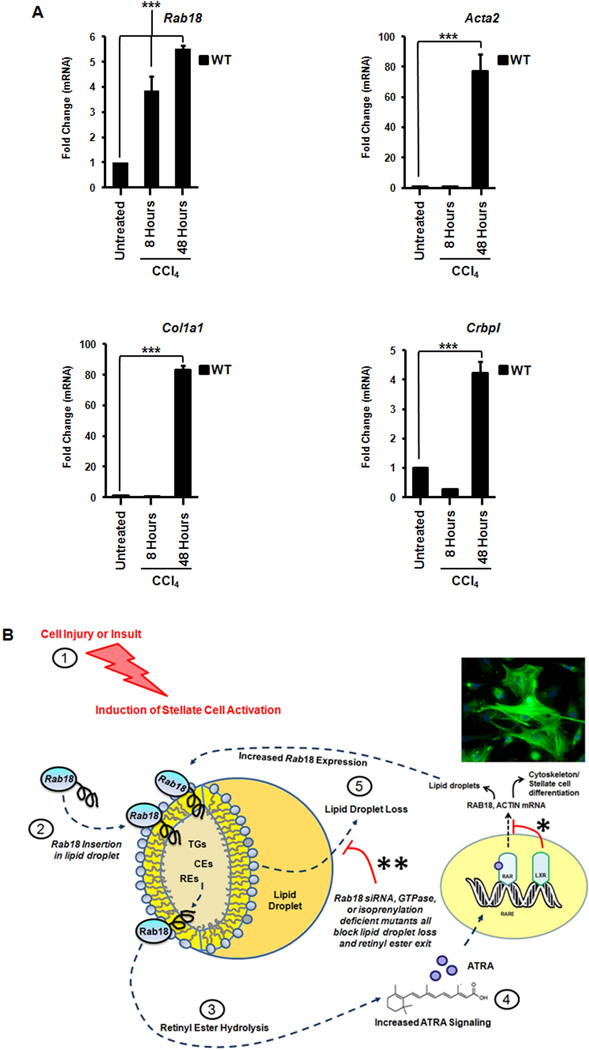

Rab18 is induced with acute liver injury

To determine whether Rab18 was specifically regulated in vivo, we employed an acute liver injury model. We injected wild-type mice (identical age and weight) with a single dose of carbon tetrachloride (Fig. 7A). Eight or forty-eight hours later the livers were harvested and Rab18 expression was measured. Rab18 was increased at eight hours post injection (Fig. 7A). Furthermore, at forty-eight hours, we demonstrate increases of α-smooth muscle actin (Acta2) and collagen (Col1a1) (Fig. 7A). The cellular retinol binding protein (Crbp1) is also increased (Fig. 7A), which is known to be important for intracellular trafficking of unesterified retinoid. Importantly, the induction of Rab18 precedes that of the fibrotic markers.

Figure 7. Rab18 is specifically induced in vivo after acute liver injury in LXR null mice.

Wild-type mice were treated with a single dose of carbon tetrachloride: 5 microliters/gram of 10% CCl4 in sterile olive oil injected intraperitoneally, for 8–48 hours. (A) Rab18 mRNA is induced in WT livers eight hours after acute injury. Fibrotic (Acta2 and Col1a1) and retinoid trafficking genes (Crbp1)are also increased, but Rab18 induction precedes these genes. All data are mean ± SEM, analyzed by two-tailed t tests: *, P < .05; **, P < .01; ***, P < .001; NS, P > .05. (B) ATRA-dependent regulation of Rab18. Stellate cell activation begins in response to external cell injury/insult (1). This leads to pre-existing Rab18 insertion into lipid droplet membranes (2) with subsequent lipid hydrolysis (3). A positive feedback loop is established as progressive hydrolysis of retinyl esters produces more ATRA and ATRA signaling (4), thereby inducing more Rab18 and lipid droplet loss (5). In WT mice, LXRs dampen this ATRA-dependent Rab18 response (*). Higher basal levels of retinyl esters in Lxrαβ−/− HSCs amplify the Rab18 response throughout this cycle. Rab18 expression is attenuated when lipid droplets are fully lost, ending the cycle. Knockdown of Rab18 by siRNA or expression of Rab18 mutants causes retention of auto-fluorescent lipid droplets (** and Fig. 5B,F), indicating a block on retinoid loss from the droplet. This correlates with diminished expression of actin and other markers of stellate cell activation. Abbreviations: TG = triglycerides, CE = cholesterol esters, RE = retinyl esters.

DISCUSSION

LXRs integrate metabolic and inflammatory functions including cholesterol trafficking, lipogenesis, and suppression of inflammation (12, 14, 23, 24). We previously showed that LXRs have anti-inflammatory and anti-fibrotic effects in HSCs and Lxrαβ−/− mice were more susceptible to developing both acute and chronic liver injury (8). These effects were due to an intrinsic property of the stellate cells, which also had notably larger lipid droplets in LXR null animals. Here we show there is a disproportionate increase of retinoid relative to cholesterol specifically in Lxrαβ−/− HSCs (Fig. 1A–C), with no change in whole liver retinoid content (Fig. 1D). LXRs therefore regulate whole body retinoid storage selectively at the level of the HSC. Since dietary cholesterol and retinoids delivered to hepatocytes enter divergent trafficking and metabolic pathways, the regulation of retinoid storage by LXRs is an unexpected discovery.

Our data demonstrate that increased retinoid content in quiescent stellate cells potentiates them for more rapid activation because of the capacity to mobilize a larger flux of retinoic acid (ATRA). Retinoid-rich Lxrαβ−/− HSCs reach maximal myofibroblastic gene expression before WT cells (Supp Fig. 3), and are therefore ‘frame-shifted’ towards quicker activation (Fig. 3E). Increased RAR signaling drives this (Fig. 2E,F), and the increased HSC retinoid is pro-fibrotic, which has been observed in humans (7, 25) and correlates with increased fibrosis in Lxrαβ−/− animals (8).

We identify Rab18 as an important mediator of lipid droplet loss and acquisition of the fibroblastic phenotype in both WT and Lxrαβ−/− HSCs (Figs. 4–6). Whether Rab18 physically interacts with retinoids remains to be determined, but rare human mutations of RAB18 cause dysfunctional retinoid metabolism leading to progressive blindness (26, 27). Rab18 was recently shown to bind cholesterol in a proteomic screen for cholesterol interacting proteins (28). The interacting partners of Rab18 at the LD surface are unknown and how Rab18 promotes RE or CE hydrolysis remains to be determined.

Increases in membrane-inserted Rab18 precede lipid droplet loss and acquisition of the fibroblastic phenotype in both WT and Lxrαβ−/− HSCs (Figs. 4–5). But the timing of retinoid responsiveness of these cells is different (Fig. 3D, 4C), suggesting that LXRs normally dampen RAR signaling in stellate cells. A role for Rab18 in lipid droplet loss is shown by siRNA knockdown which causes retention of stellate cell lipid droplets and inhibits markers of activation (Fig. 5B & Supp Fig. 8). Furthermore, modulation of either the GTPase activity or insertion into droplet membranes inhibits the phenotypic progression of HSC activation (Fig. 5E,F). ATRA treatment induces Rab18, promoting LD loss and the activated, myofibroblastic state (Fig. 4, 6). We firmly establish an important role for the GTPase activity and cellular localization of Rab18 in WT cells (Figs. 5E,F; 6E). This is the first study demonstrating that blocking lipid droplet loss slows primary HSC activation in culture. Future studies will focus on Rab18 as the fulcrum between retinoid and cholesterol metabolism as modulation of Rab18 expression, its GTPase activity, and its intracellular localization could all impact fibrosis.

We propose an ATRA-based positive feedback model (Fig. 7B) where liver injury triggers insertion of Rab18 into stellate cell lipid droplet membranes. This scaffold at the droplet surface promotes hydrolysis and trafficking of lipid to endosomes or other compartments. As retinyl ester hydrolysis proceeds, more ATRA is formed, with increased RAR signaling in the nucleus. Since Lxrαβ−/− HSCs have increased starting retinoid content, they have higher basal levels of ATRA and downstream RAR signaling, and experience earlier induction of Rab18 to potentiate lipid droplet loss and more rapid acquisition of the activated phenotype. This is seen both in the culture activation model (Figure 4) and suggested by the induction of Rab18 before fibrotic markers in vivo (Figure 7A). The idea that Rab-GTPases mediate lipid interactions with endosomes has been suggested and demonstrated by other investigators (29). In this context, Rab18 is the relevant Rab-GTPase for stellate cells as it dynamically modulates both lipid droplet size and cellular activation. Interference with Rab18 may therefore have significant therapeutic benefit in ameliorating liver fibrosis.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

FINANCIAL SUPPORT: This work was supported by NIH grants K08-DK088998 (SWB) and R01-DK068437 (WSB), and a UCLA CURE Pilot and Feasibility Study Grant (FOM).

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

- LXR

liver X receptor

- HSC

hepatic stellate cell

- LD

lipid droplet(s)

- CE

cholesterol ester(s)

- RE

retinyl ester(s)

- RAR

retinoic acid receptor

- ATRA

all-trans retinoic acid

- LPS

lipopolysaccharide

- RP

retinyl palmitate

REFERENCES

- 1.Mederacke I, Hsu CC, Troeger JS, Huebener P, Mu X, Dapito DH, Pradere JP, et al. Fate tracing reveals hepatic stellate cells as dominant contributors to liver fibrosis independent of its aetiology. Nat Commun. 2013;4:2823. doi: 10.1038/ncomms3823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Friedman SL. Hepatic stellate cells: protean, multifunctional, and enigmatic cells of the liver. Physiol Rev. 2008;88:125–172. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00013.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blaner WS, O'Byrne SM, Wongsiriroj N, Kluwe J, D'Ambrosio DM, Jiang H, Schwabe RF, et al. Hepatic stellate cell lipid droplets: A specialized lipid droplet for retinoid storage. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1791:467–473. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2008.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Friedman SL, Roll FJ, Boyles J, Bissell DM. Hepatic lipocytes: the principal collagen-producing cells of normal rat liver. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1985;82:8681–8685. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.24.8681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kluwe J, Wongsiriroj N, Troeger JS, Gwak GY, Dapito DH, Pradere JP, Jiang H, et al. Absence of hepatic stellate cell retinoid lipid droplets does not enhance hepatic fibrosis but decreases hepatic carcinogenesis. Gut. 2011;60:1260–1268. doi: 10.1136/gut.2010.209551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Okuno M, Moriwaki H, Imai S, Muto Y, Kawada N, Suzuki Y, Kojima S. Retinoids exacerbate rat liver fibrosis by inducing the activation of latent TGF-beta in liver stellate cells. Hepatology. 1997;26:913–921. doi: 10.1053/jhep.1997.v26.pm0009328313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Geubel AP, De Galocsy C, Alves N, Rahier J, Dive C. Liver damage caused by therapeutic vitamin A administration: estimate of dose-related toxicity in 41 cases. Gastroenterology. 1991;100:1701–1709. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(91)90672-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Beaven SW, Wroblewski K, Wang J, Hong C, Bensinger S, Tsukamoto H, Tontonoz P. Liver X receptor signaling is a determinant of stellate cell activation and susceptibility to fibrotic liver disease. Gastroenterology. 2011;140:1052–1062. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.11.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tontonoz P, Mangelsdorf DJ. Liver X receptor signaling pathways in cardiovascular disease. Mol Endocrinol. 2003;17:985–993. doi: 10.1210/me.2003-0061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.O'Byrne SM, Wongsiriroj N, Libien J, Vogel S, Goldberg IJ, Baehr W, Palczewski K, et al. Retinoid absorption and storage is impaired in mice lacking lecithin:retinol acyltransferase (LRAT) J Biol Chem. 2005;280:35647–35657. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M507924200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bielawski J, Pierce JS, Snider J, Rembiesa B, Szulc ZM, Bielawska A. Comprehensive quantitative analysis of bioactive sphingolipids by high-performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. Methods Mol Biol. 2009;579:443–467. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60761-322-0_22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Beaven SW, Matveyenko A, Wroblewski K, Chao L, Wilpitz D, Hsu TW, Lentz J, et al. Reciprocal regulation of hepatic and adipose lipogenesis by liver × receptors in obesity and insulin resistance. Cell Metab. 2013;18:106–117. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2013.04.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moriwaki H, Blaner WS, Piantedosi R, Goodman DS. Effects of dietary retinoid and triglyceride on the lipid composition of rat liver stellate cells and stellate cell lipid droplets. J Lipid Res. 1988;29:1523–1534. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Joseph SB, Castrillo A, Laffitte BA, Mangelsdorf DJ, Tontonoz P. Reciprocal regulation of inflammation and lipid metabolism by liver X receptors. Nat Med. 2003;9:213–219. doi: 10.1038/nm820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bensinger SJ, Tontonoz P. Integration of metabolism and inflammation by lipid-activated nuclear receptors. Nature. 2008;454:470–477. doi: 10.1038/nature07202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hellemans K, Verbuyst P, Quartier E, Schuit F, Rombouts K, Chandraratna RA, Schuppan D, et al. Differential modulation of rat hepatic stellate phenotype by natural and synthetic retinoids. Hepatology. 2004;39:97–108. doi: 10.1002/hep.20015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Senoo H, Wake K. Suppression of experimental hepatic fibrosis by administration of vitamin A. Lab Invest. 1985;52:182–194. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ulven SM, Natarajan V, Holven KB, Lovdal T, Berg T, Blomhoff R. Expression of retinoic acid receptor and retinoid X receptor subtypes in rat liver cells: implications for retinoid signalling in parenchymal, endothelial, Kupffer and stellate cells. Eur J Cell Biol. 1998;77:111–116. doi: 10.1016/S0171-9335(98)80078-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vogel S, Piantedosi R, Frank J, Lalazar A, Rockey DC, Friedman SL, Blaner WS. An immortalized rat liver stellate cell line (HSC-T6): a new cell model for the study of retinoid metabolism in vitro. J Lipid Res. 2000;41:882–893. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Martin S, Parton RG. Characterization of Rab18, a lipid droplet-associated small GTPase. Methods Enzymol. 2008;438:109–129. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(07)38008-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Xu L, Hui AY, Albanis E, Arthur MJ, O'Byrne SM, Blaner WS, Mukherjee P, et al. Human hepatic stellate cell lines, LX-1 and LX-2: new tools for analysis of hepatic fibrosis. Gut. 2005;54:142–151. doi: 10.1136/gut.2004.042127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee TF, Mak KM, Rackovsky O, Lin YL, Kwong AJ, Loke JC, Friedman SL. Downregulation of hepatic stellate cell activation by retinol and palmitate mediated by adipose differentiation-related protein (ADRP) J Cell Physiol. 2010;223:648–657. doi: 10.1002/jcp.22063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zelcer N, Hong C, Boyadjian R, Tontonoz P. LXR regulates cholesterol uptake through Idol-dependent ubiquitination of the LDL receptor. Science. 2009;325:100–104. doi: 10.1126/science.1168974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Beaven SW, Tontonoz P. Nuclear receptors in lipid metabolism: targeting the heart of dyslipidemia. Annu Rev Med. 2006;57:313–329. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.57.121304.131428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stimson WH. Vitamin A Intoxication in Adults. N Engl J Med. 1961;265:369–373. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Huang AS, Kim LA, Fawzi AA. Clinical characteristics of a large choroideremia pedigree carrying a novel CHM mutation. Arch Ophthalmol. 2012;130:1184–1189. doi: 10.1001/archophthalmol.2012.1117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bem D, Yoshimura S, Nunes-Bastos R, Bond FC, Kurian MA, Rahman F, Handley MT, et al. Loss-of-function mutations in RAB18 cause Warburg micro syndrome. Am J Hum Genet. 2011;88:499–507. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2011.03.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hulce JJ, Cognetta AB, Niphakis MJ, Tully SE, Cravatt BF. Proteome-wide mapping of cholesterol-interacting proteins in mammalian cells. Nat Methods. 2013;10:259–264. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Walther TC, Farese RV., Jr The life of lipid droplets. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1791:459–466. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2008.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.