Abstract

Although most paediatric hair loss presenting to clinicians is due to alopecia areata, unusual patterns should prompt a careful history.

Keywords: trichotillomania, trichotemnomania, alopecia areata

A 12-year-old boy presented with a three-year history of bilateral loss of eyelashes from upper and lower eyelids without associated pruritus or scale. Symptoms included soreness of the eyes associated with external foreign bodies, such as dust. There were no reports of increased fall of hair and no history of hair loss at other sites, including the scalp. He had no personal or family history of atopy or autoimmune diseases. Prior to the onset of symptoms, the patient was witnessed to cut his eyelashes with the use of small nail clippers; however, following this event the eyelashes did not re-grow.

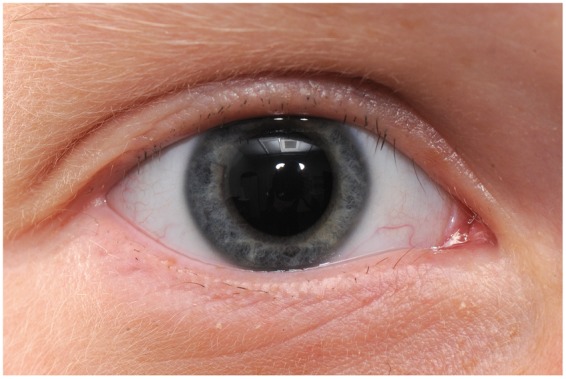

On examination, the patient had multiple broken hairs along the upper and lower eyelid margins (Figure 1). No exclamation marks and no corkscrew or comma-shaped hairs were seen on magnification. The scalp hair appeared intact with normal hair shaft morphology. The skin appeared normal over the eyelids and at all other sites. He had Fitzpatrick type II skin and hair and skin pigmentations were preserved.

Figure 1.

Multiple broken hairs along the upper and lower eyelid margins.

Trichotemnomania is a distinct obsessive-compulsive habit of cutting or shaving the hair,1 whereas Trichotillomania (TTM) is the compulsion to remove one’s own hair by pulling and is conventionally observed as bizarre and irregularly shaped patches of non-scarring alopecia with short, broken hairs on the scalp. In adults, an increased emotional feeling of tension before the hair is pulled and a sense of relief once the hair is removed is documented.2 In younger children, TTM seems to more often represent a habit or manifestation of mild frustrations or anxiety, akin to thumb-sucking or nail-biting, that often settles, whereas in teenagers and adults it may represent a more significant underlying psychological disorder. Paediatric TTM is estimated to have a point prevalence of approximately 0.5% and a lifetime prevalence of 0.6%–3.4% in adults, most of whom began pulling as children.3 Childhood TTM is slightly more common in boys, but women outnumber men by up to 7:1 in the adult form.2

It has been reported that children with TTM pull their hair from the scalp, eyebrows, eyelashes, pubic regions, perianal, nasal, ear and abdominal sites. Hair pulling tends to be biased toward the side of a patient’s handedness and simultaneous TTM of eyelash and eyebrow is especially common among prepubertal children.4

The differential diagnosis includes alopecia areata (AA) but the presence of structurally normal, short, firmly anchored, broken hairs and lack of tapered dystrophic exclamation-mark hairs typical of AA usually permit the distinction to be made. Dermoscopy may also be helpful in distinguishing TTM from AA and from tinea infections, although this technique is more technically challenging when examining a young child. Black dots represent broken hairs within follicular ostia but these may also be seen in AA. The absence of exclamation mark hairs and the presence of coiled hairs, representing broken hairs that curl back in telogen or catagen, are more suggestive of TTM.2

TTM can lead to medical complications such as skin irritation or infections on the affected sites and is associated with developmental co-morbidities. Empirical evidence suggests that about 70% of children with TTM may also meet diagnostic criteria for other psychiatric diagnoses.5 Generalised anxiety, social phobia, obsessive-compulsive disorder, attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder and oppositional defiant disorder were among the most common diagnoses.6

Habit reversal techniques, behaviour modification strategies, selective serotonin re-uptake inhibitors, tricyclic antidepressants, neuroleptics, monoamine oxidase inhibitors, mood stabilisers, anxiolytics and opiate antagonists have been used with some success in adults. Van Amerigen et al.7 found olanzapine to be superior to placebo for the treatment of TTM measured using the Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive scale. The treatment and follow-up period were short (12 weeks) but results suggested that TTM may lie on the obsessive-compulsive spectrum of disorders, characterised by compulsive urges and ritualised behaviours.

A study by Grant et al., demonstrated statistically significant reduction in TTM symptoms in adults treated with the glutamate modulator N-acetylcysteine for 12 weeks compared to placebo as measured using the Massachusetts General Hospital Hair Pulling Scale. Although it was ineffective in 44% of treated patients, the study supports the hypothesis that pharmacologic manipulation of the glutamate system (in the nucleus accumbens) may target core symptoms of compulsive behaviors.8

Topical Latanoprost prolongs the anagen portion of the hair cycle; however, this treatment is not licensed for use in children and adverse effects include permanent heterochromia.9 Systemic exposure to Latanoprost acid was observed more frequently in younger children than in adolescents and adults, attributed to lower body weight and smaller blood volume,10 making this treatment unsuitable in children. It is also unlikely that increasing hair growth rate would be of clinical benefit in this case without managing the underlying problem.

TTM can be debilitating and the treatment of patients with this condition can be challenging. The use of behavioural therapy, sometimes in combination with psychotropic drugs, can be useful.4

This case was considered to be due to continued trauma by the patient either by trimming or plucking of the eyelash hairs. Cognitive behavioural therapy and acceptance and commitment therapy, given by the paediatric psychotherapy team were of little benefit and this difficult problem persists.

Declarations

Competing interests

None declared

Funding

None declared

Guarantor

NJL

Ethical approval

Written informed consent for publication was obtained from the patient’s mother.

Contributorship

NJL is responsible for the care of the patient. NJL and AEM conceived the idea for the case report and RVV wrote and revised the paper. All authors approved the final version.

Acknowledgements

None

Provenance

Not commissioned; peer-reviewed by Cristina Rodriguez

References

- 1.Happle R. Trichotemnomania: obsessive-compulsive habit of cutting or shaving hair. J Am Acad Dermatol 2005; 52:1: 157–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Messenger AG. Trichotillomania. In: Burns T, Breathnach S, Cox N, Griffiths C. (eds). Rook’s textbook of dermatology, West Sussex: Wiley-Blackwell, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bruce TO, Barwick LW, Wright HH. Diagnosis and management of trichotillomania in children and adolescents. Pediatr Drugs 2005; 7: 365–376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yong-Kwang T, Levy ML, Metry DW. Trichotillomania in childhood: case series and review. Pediatrics 2004; 113: 494–498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reeve EA, Bernstein GA, Christenson GA. Clinical characteristics and psychiatric comorbidity in children with trichotillomania. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1992; 31: 132–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Flessner CA. Cognitive behavior therapy for childhood repetitive behaviour disorders: tic disorders and Trichotillomania. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am 2011; 20: 319–328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Van Amerigen M, Mancini C, Patterson B, Bennett M, Oakman J. A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of olanzapine in the treatment of trichotillomania. J Clin Psychiatry 2010; 71: 1336–1343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grant J, Odlaug B, Kim SW. N-Acetylcysteine, a Glutamate Modulator, in the treatment of trichotillomania, a double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2009; 66: 756–763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stjernschantz JW, Albert DM, Dan-Ning H, et al. Mechanism and clinical significance of prostaglandin-induced iris pigmentation. Surv Ophthalmol 2002; 47: 162–175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Raber S, Courtney R, Tomoko MC, et al. Latanoprost systemic exposure in pediatric and adult patients with glaucoma: a phase 1, open-label study. Ophthalmology 2011; 118: 2022–2027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]