Abstract

Background

Urea cycle disorders are caused by dysfunction in any of the six enzymes and two transport proteins involved in urea biosynthesis. Our study focuses on Ornithine Transcarbamylase deficiency (OTCD), an X-linked disorder that results in a dysfunctional mitochondrial enzyme, which prevents the synthesis of citrulline from carbamoyl phosphate and ornithine. This enzyme deficiency can lead to hyperammonemic episodes and severe cerebral edema. The objective of this study was to use a cognitive battery to expose the cognitive deficits in asymptomatic carriers of OTCD.

Materials and Methods

In total, 81 participants were recruited as part of a larger urea cycle disorder imaging consortium study. There were 25 symptomatic participants (18 female, 7 male, 25.6 years ± 12.72 years), 20 asymptomatic participants (20 female, 0 male, 37.6 years ± 15.19 years), and 36 healthy control participants (21 female, 15 male, 29.8 years ± 13.39 years). All participants gave informed consent to participate and were then given neurocognitive batteries with standard scores and T scores recorded.

Results

When stratified by symptomatic participant, asymptomatic carrier, and control, the results showed significant differences in measures of executive function (e.g. CTMT and Stroop) and motor ability (Purdue Assembly) between all groups tested. Simple attention, academic measures, language and non-verbal motor abilities showed no significant differences between asymptomatic carriers and control participants, however, there were significant differences between symptomatic and control participant performance in these measures.

Conclusions

In our study, asymptomatic carriers of OTCD showed no significant differences in cognitive function compared to control participants until they were cognitively challenged with fine motor tasks, measures of executive function, and measures of cognitive flexibility. This suggests that cognitive dysfunction is best measurable in asymptomatic carriers after they are cognitively challenged.

Keywords: Urea Cycle Disorders, Cognitive function, Asymptomatic Carriers, Metabolic Disease, Ornithine Transcarbamylase Deficiency

1. Introduction

Urea cycle disorders (UCDs) result from deficiencies in any of six enzymes and two transport proteins involved in the urea cycle or synthesis of urea. Ornithine transcarbamylase deficiency (OTCD) results from a mutation in the ornithine transcarbamylase mitochondrial enzyme that normally catalyzes the synthesis of citrulline from carbamoyl phosphate and ornithine1. It is the only urea cycle disorder that is X-linked, and as a result, males and females are differentially affected2-5. The true incidence of this disorder is unknown, due to its rarity, however the estimated combined incidence for all UCDs ranges from 1 in 8,200 to 1 in 30,0001,6.

A deficiency of ornithine transcarbamylase leads to an excess of ammonia being generated by the urea cycle instead of urea1. Elevation of ammonia alters several amino acid pathways and neurotransmitter systems, interferes with cerebral energy metabolism, nitric oxide synthesis, oxidative stress and signal transduction pathways. The only route of ammonia disposal is via the glutamine synthesis pathway, generating an excess of glutamine in the brain, and astrocytes are the only cellular compartment in the brain capable of glutamine (gln) synthesis. These high levels of glutamine are believed to cause a shift in osmotic gradient within the brain, causing excessive fluid to cross the blood brain barrier, leading, often, to severe edema1. Although not universally accepted, gln is a prime suspect in the list of neurotoxins associated with the neurological aspects of OTCD. Vomiting, lethargy, and coma can characterize severe episodes of hyperammonemia; however, mild cases often go unrecognized and undetected. If uncontrolled or untreated this can lead to episodic encephalopathy and ultimately result in brain injury and death1,7.

Many have investigated the cognitive insults resulting from hyperammonemic encephalopathy in OTCD2-4. Our study examined the effects of OTCD on motor skills, simple and complex attention, executive function, verbal and nonverbal memory, and language skills in a cohort of children and adults with OTCD ascertained due to having an affected sibling, father, or other family member. Those who participated were enrolled in an NIH funded neuroimaging study as part of the Urea Cycle Rare Disorders Consortium. Our study offers a unique perspective on cognitive deficits in OTCD because there is a wide range of ages (7 – 60 yrs) and participant scores were stratified by asymptomatic carriers, symptomatic participants, and an age and gender-matched control population, which is often not possible due to the rarity of this disorder. The goal of this study was to elucidate potential cognitive tasks that were more sensitive to the cognitive deficits in carriers of OTCD.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1 Participants

Participants with OTCD, both symptomatic and asymptomatic carriers, were recruited through the Online Rare Diseases Clinical Research Network registry, the National Urea Cycle Disorders Foundation, the Society for Inherited Metabolic Disease, and colleagues of the principal investigator known to service OTCD patients in metabolic clinics across the country. Participants with OTCD had molecular confirmation if available or clinical phenotype with symptoms including protein intolerance, emesis, or unexplained encephalopathy or psychiatric disease with appropriate biochemical findings. Participants were stable at the time of the evaluation and had normal ammonia levels. Asymptomatic carriers were relatives of affected individuals recruited for this study. One-third reported dietary protein aversion.

Control participants were matched to OTCD participants based on age and gender. Control participants were recruited via IRB-approved advertisements posted throughout the Georgetown University Hospital, medical school, and graduate school. All were consuming a normal diet. Individuals with a past medical history of epilepsy, stroke, cognitive dysfunction, liver disease, psychiatric illness, or who scored below 80 on the WASI were excluded from this study. Participants were at baseline health at the time of the study (i.e. not directly before or after a HA).

Participants with OTCD, who had molecular confirmation were subdivided into symptomatic or asymptomatic groups based on results of previous stable isotope studies, if available, or clinical phenotype with symptoms including protein intolerance, emesis, or unexplained encephalopathy or psychiatric disease with appropriate biochemical findings. Overall, there were 81 participants with an age range of 7-60 years (Table 1). There were 25 symptomatic participants (18 female, 7 male, 25.6 years ± 12.72 years), 20 asymptomatic participants (20 female, 0 male, 37.6 years ± 15.19 years), and 36 healthy control participants (21 female, 15 male, 29.8 years ± 13.39 years), who gave informed consent. The informed consent was approved by the Children's National Medical Center Biomedical Institutional Review Board and given to all participants prior to performing the experiment.

Table 1.

Age distribution of study participants, showing also percent of subjects of each age range.

| Age Range (yrs) | Percent of Population (%); N |

|---|---|

| 5-10 | 6; (5) |

| 11-19 | 15; (12) |

| 20-29 | 31; (25) |

| 30-39 | 19; (15) |

| 40-49 | 11; (9) |

| 50-59 | 17; (14) |

| 60+ | 1; (1) |

2.2 Cognitive Assessment

We investigated neurocognitive performance differences between OTCD participants (symptomatic participants and asymptomatic carriers) and control participants using the assessment battery detailed below. All scores were normalized to age allowing comparison across age groups. (Table 2)

Table 2.

Description of cognitive battery administered and the specific cognitive measures each task measures.

| Cognitive Assessment | Academic | Executive Function | Verbal Memory | Simple Attention | Non-Verbal Memory | Motor Dexterity | Language |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stroop | X | ||||||

| CTMT | X | ||||||

| Brief | X | ||||||

| Digit Span | X | X | |||||

| WASI | X | X | X | ||||

| VMI | X | ||||||

| PA | X | ||||||

| EVT | X | ||||||

| PPVT-III | X | ||||||

| WJ-III | X | X |

2.2.1 Assessment of Executive Function

The Stroop

The Stroop is used to assess executive function levels through measurements of processing speed, simple and complex reaction time, speed-accuracy trade off, and inhibition and selective attention. Participants are required to indicate the color of a word flashed on a screen. The words, “red,” “blue,” or “green,” are displayed in either the corresponding color (congruent trials, e.g. “red” is written in the color red) or a conflicting color (incongruent trials, e.g. “blue” is written in the color green) 8.

The Comprehensive Trail-Making Test (CTMT)

The CTMT is a measure of set-shifting, working memory, divided attention, and cognitive flexibility. Numbers are presented as Arabic numerals (e.g. 1, 8) or spelled out in English (e.g. three). CTMT trials 1–3 require only simple sequencing skills. Trails 4 and 5 (part B), in contrast, require a higher level of “set shifting” or cognitive flexibility analysis. Trail 4 introduces both numerical and lexical number stimuli as targets requiring the participant to locate targets regardless of appearance. CTMT Trail 5 requires the examinee to connect a series of numbers and letters in a specific sequence as quickly as possible without crossing lines9.

The Behavior Rating Inventory for Executive Functioning (BRIEF)

The BRIEF is a self-report measure that captures the individual's self-perceived executive function. Participants are required to complete a series of questions that assess the individual on eight clinical scales (Inhibit, Shift, Emotional Control, Initiate, Working Memory, Plan/Organize, Organization of Materials, and Monitor). Individuals are then scored on two indices: the Behavior Rating Index (BRI), which measures an individual's ability to control his or her behavior and emotional responses and the Metacognitive Index (MI), which measures an individual's ability to systematically solve problems through planning and organizing in a variety of contexts 10.

Digit span backwards as part of the Wechsler Intelligence Scale (WIS)

The digit span backwards task measures a participant's working-memory capacity, attention, information manipulation abilities, and the ability to remember multiple pieces of information. For the digit span backwards, participants are presented orally with a series of digits (e.g., ‘1, 7, 9’) and must immediately repeat the series of digits in the reverse order. Those able to repeat the series back correctly are then given a longer series of numbers until they are unable to successfully complete the task11, 12.

2.2.2 Verbal Memory

The Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of intelligence (WASI) – Verbal Subtest

The WASI Verbal IQ (including the Vocabulary and Similarities tasks) is an assessment of verbal memory. The WASI Vocabulary task measures word knowledge, verbal concept formation, and fund of knowledge. The Vocabulary task consists of 38 items that the examiner states orally and presents visually; the examinee is required to define the word. The Similarities task measures verbal reasoning and concept formation. For this task, a pair of words is presented orally and the examinee must describe a shared trait between the two words (e.g., grape and strawberry are both fruits) 11.

2.2.3 Simple Attention

Digit span forward subtest of the Wechsler Intelligence Scale

Digit span forward is an assessment of an individual's simple attention. For the digit span forward, participants are presented orally with a series of digits (e.g., ‘1, 7, 9’) that the participant must immediately repeat in the same order. If able to repeat the series correctly, the participant is given a longer list of numbers until he/she is no longer able to successfully complete the task 12.

2.2.4 Non-verbal Memory

Beery-Buktenica Developmental Test of Visual-Motor Integration (VMI)

The VMI evaluates visual and motor integration, visual discrimination, fine motor skills, and visual perception. The examinee is required to reproduce 18 large geometric figures that are sequenced in order of increasing difficulty (e.g., from drawing lines, to closed figures [e.g., circles and squares], to embedded figures [e.g., 3 overlapping circles], to joined figures [e.g., a square touching a circle])13.

The Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence (WASI) – Performance Subtest

The WASI Performance IQ examines non-verbal memory (including the Matrix Reasoning and Block Design tasks). The WASI Matrix Reasoning evaluates visual information processing and abstract reasoning skills. This task consists of a series of 35 grid patterns, from which the examinee must select the image that is consistent with the pattern. The Block Design assesses the ability to analyze and synthesize abstract visual stimuli, nonverbal concept formation, visual perception and organization, simultaneous processing, visual-motor coordination, learning, and the ability to separate figure from background in visual stimuli. For this task, the participant is given a picture of a two-dimensional geometric pattern and is then asked to replicate it using nine two-color cubes in a given amount of time. The participant completes 13 patterns of increasing difficulty unless two successive failed attempts occur11.

2.2.5 Fine Motor Dexterity

Purdue Pegboard (PP)

The Purdue Pegboard test assesses motor functioning by requiring the participant to place pegs in two rows on a pegboard. Participants complete this task first with their left hand, then their right hand, and finally with both hands 14.

2.2.6 Language

Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test-Third Edition (PPVT-III)

The PPVT-III is a measure of receptive vocabulary skills for individuals between the ages of 2 and 90 years. Four pictures are displayed in a stimulus book and the participant is required to indicate which picture best matches the word spoken by the examiner15.

Expressive Vocabulary Test (EVT)

The EVT measures expressive vocabulary by asking the participant to name pictures displayed in a stimulus book. As the test advances to more difficult items, participants are asked to produce synonyms for words given in carrier phrases and represented in pictures16.

Woodcock Johnson III tests of achievement (WJ-III) – Oral Comprehension

WJ-III is a psychological and educational evaluation of individuals that is useful in identifying learning deficits. The Oral Comprehensive subtest of the WJ-III assesses listening ability and language comprehension. Individuals complete this task by providing the missing word for an orally delivered sentence. For example, “cars almost always have four _____.”17

2.2.7 Academic Performance

Woodcock Johnson III tests of achievement (WJ-III) – Passage Comprehension

The Passage Comprehension subtest of WJ-III evaluates language and reading comprehension. Participants read a passage on their own and then answer fill in the blanks based on the story they previously read. At the beginning of the test, there is a picture to help cue the individual, but as the difficulty increases, picture cues are taken away. For example, “there are many tall buildings in most _____.”The picture would show a city with large buildings (answer is cities or towns) 18.

Woodcock Johnson III tests of achievement (WJ-III) – Calculation

The Calculation subtest of WJ-III measures math achievement and quantitative reasoning. Participants perform mathematical calculations, such as 2 + 2 18.

The Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of intelligence (WASI)

The Full IQ of the WASI is a combination of both the Verbal and Performance IQ subtests described previously. The Full IQ of the WASI measures an individual's verbal, nonverbal, and general cognitive functioning11.

2.3 Statistical Analysis

Normality of each standardized score obtained on the neurocognitive battery was assessed for normality using the Shapiro-Wilk normality test. Participants were separated into the three groups: symptomatic participants, asymptomatic carriers, and control participants. The median of each standardized score for each cognitive assessment was obtained; all standardized scores were normalized to age of a participant based on general population studies and the standardized norm referenced scores available for each test. The median of the standardized scores for each group were then compared using analysis of variance (ANOVA) within each subject group for normalized data and Kruskal Wallis tests for non-normalized data. A significance threshold of P < 0.05 was used. To avoid false significance, the p values were adjusted for multiple comparisons. To account for any possible effects of age or sex, all values were co-varied with these phenotypes.

3. Results

Executive function was measured using the BRIEF (MI and BRI), CTMT (Trail 4, 5, and B) and the Digit Span backwards subtest of the WJ-III. The Digit Span backwards results showed no significant difference between any participant groups.

The symptomatic participants demonstrated several deficits in comparison with the control participants on the BRIEF, both the BRI and the MI. The median of standardized scores for the BRI of the symptomatic participants was 53 [(38-70); n=24], the median for asymptomatic participants was 52 [(35-72); n=16], and the median for control participants was 44 [(36-75); n=33]. The only significant difference observed was between the symptomatic participants’ scores and the control participants’ scores, p=0.001. (Table 3)

Table 3.

Significant results stratified by participant group and cognitive measure assessed.

| Function Tested | Control Participant | Asymptomatic Carrier | Symptomatic Patient | Significant Differences |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Executive Function | ||||

| Brief – BRI | 44 (36-75); 33 | 52 (35-72); 16 | 53 (38-70); 24 | C vs S P=0.001 |

| Brief – MI | 46 (39-68); 33 | 51 (38-73); 16 | 55 (39-83); 24 | C vs S p=0.04 |

| CTMT – Trail 4 | 52 (30-75); 27 | 48 (40-64); 13 | 42 (18-62); 18 | C vs S p=0.002 S vs A p=0.04 |

| CTMT – Trail 5 | 56 (38-79); 27 | 49 (29-59); 13 | 40 (18-59); 18 | C vs S p<0.0001 |

| CTMT – Trail B | 54 (36-75); 27 | 50 (36-61); 13 | 40 (18-61); 18 | C vs S p<0.0001 S vs A p=0.02 |

| Digit Span Backwards | 13 (7-19); 21 | 11 (8-16); 5 | 7 (5-18); 5 | NS |

| Stroop – Incongruent Stimulus (ms) | 878 (595-1492) | 980 (628-1749) | 1158 (556-1986) | C vs S p=0.001 |

| Stroop – Incongruent - Congruent | 193 (0-732) | 291 (96-1046) | 304 (−294 – 1204) | C vs S p=0.034 C vs A p=0.048 |

| Verbal Memory | ||||

| WASI – Verbal IQ | 120 (95-138); 33 | 113 (92-127); 17 | 101 (76-131); 22 | C vs S p<0.0001 |

| Simple Attention | ||||

| Digit Span Forwards | 13 (7-18); 21 | 11 (8-16); 5 | 11 (11-18); 5 | NS |

| Stroop – Congruent Stimulus (ms) | 637 (509-1230) | 644 (489-812) | 692 (536-1548) | NS |

| Non-Verbal Memory | ||||

| VMI- Motor | 95 (73-107); 21 | 86 (61-95); 4 | 70 (58-85); 4 | C vs S p=0.002 |

| WASI – Performance IQ | 120 (95-138); 21 | 113 (92-127); 16 | 101 (76-131); 21 | C vs S p<0.0001 |

| Motor | ||||

| Purdue Assembly | −0.31 (−1.92-1.48); 20 | −3.31 (−3.96- −0.56); 4 | −1.91 (−4.63- −0.22); 5 | C vs S p=0.04 C vs A p=0.01 |

| Language | ||||

| PPVT | 120 (88-136); 23 | 108 (93-122); 4 | 103 (92-114); 4 | NS |

| EVT | 119 (111-151); 23 | 112 (96-122); 4 | 94 (82-101); 4 | NS |

| WJ-III Oral Comprehension | 109 (96-121); 20 | 110 (98-132); 4 | 98 (88-109); 4 | NS |

| Academic | ||||

| WJ-III Calculation | 118 (80-144); 20 | 109 (93-144); 4 | 81 (112-75); 4 | C vs. S p=0.001 |

| WJ-III Passage Comprehension | 114 (96-133); 20 | 112 (98-120); 4 | 97 (92-100); 4 | C vs. S p=0.004 |

| WASI – Full IQ | 124 (92-140); 31 | 111 (100-125); 16 | 101 (78-134); 21 | C vs. S p < 0.0001 |

(C= control participant, A= asymptomatic carrier, S = symptomatic patient)

Similarly, the MI revealed a significant difference between the standardized scores of the symptomatic participants, 55 [(39-83); n=24], and the standardized scores of the control participants, 46 [(39-68); n=50, p=0.04]; however, no significant difference between the asymptomatic carriers and the control participants or the symptomatic participants was found. (Table 3)

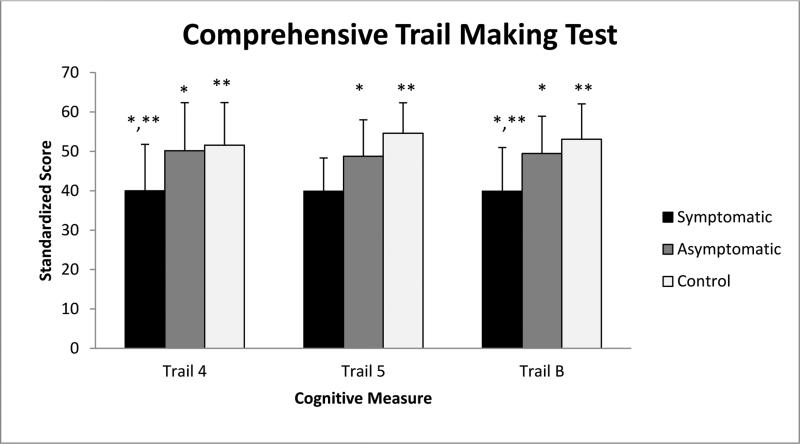

On the CTMT, the symptomatic participants scored significantly lower than both the asymptomatic carrier participants and the control participants. On Trail 4, the median standardized score of the symptomatic participants was 42 [(18-62); n=18], which is significantly different from the median of the asymptomatic participant scores, 48 [(40-64); n=13, p=0.04], and the median of the control participants’ scores, 52 [(30-75); n=27, p=0.002] (Figure 1). Similarly, on Trail B, the median symptomatic participants’ standardized score was 40 [(18-61); n=18] compared with the median asymptomatic carrier participants’ score of 50 [(36-61); n=13, p=0.02] and the median of the control participant score of 54 [(36-75); n=27, p<0.0001] (Figure 1). On Trail 5, the median of the symptomatic participants’ scores was 40 [(18-59); n=18], compared with the median of the asymptomatic carrier participant scores, 49 [(29-59); n=13] and the median of the control participants’ scores, which was 56 [(38-79); n=27] (Figure 1). The only significant difference observed was between symptomatic participants and the control participants, p<0.0001 (Table 3).

Figure 1.

Significant differences between participant groups performance on the CTMT, Trails 4, 5 and B

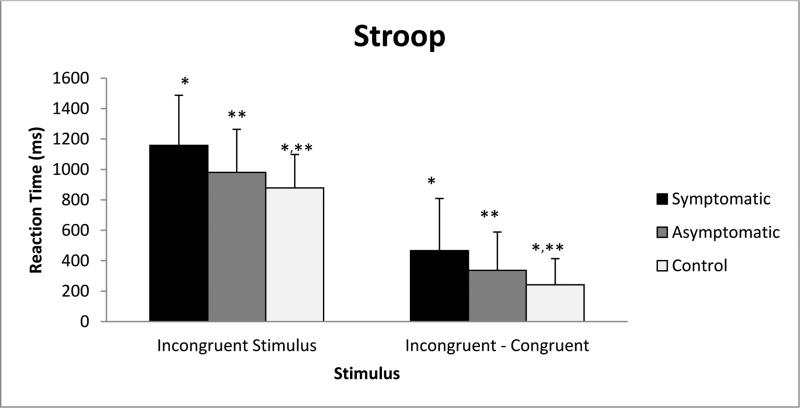

The Stroop incongruent stimuli task was analyzed using the median of the reaction time. There was a significant difference between symptomatic participants’ reaction times, 1158 ms [(556-1986); n=22], and control participants’ reaction times, 878 [(595-1492); n=33, p=0.001] for incongruent stimuli. The median of the reaction times for the congruent task was subtracted from the median of the reaction times for the incongruent task. The resulting number was used as a measure of cognitive flexibility and executive function8. The symptomatic participants showed a difference in reaction time of 304 ms [(−294 – 1204); n=22] between congruent and incongruent tasks, which was significantly different from the control participants’ difference in reaction time of 193 ms [(0-732); n=33, p=0.048]. The asymptomatic participants had a difference of 291ms [(96-1046); n=17] in performance between congruent and incongruent stimuli, which was significantly different from control participant performance (p=0.034). (Figure 2, Table 3)

Figure 2.

Significant differences between participant groups performance on the Stroop, recorded as reaction time versus stimulus.

Verbal Memory was measured with the Verbal IQ subtest of the WASI. The median for symptomatic participants Verbal IQ was 101 [(76-131); n=22] though not considered cognitively impaired, the median of the asymptomatic carriers’ verbal IQ was 113 [(92-127); n=17], and the median of the control participants was the highest verbal IQ, 120, which was significantly different from symptomatic participants [(95-138); n=33, p<0.0001). (Table 3)

Simple Attention was assessed with the digit span forward subtest of the WJ-III and the congruent stimuli on the Stroop. There was no significant difference between any of the participant groups. (Table 3)

Non-verbal memory skills were determined with the VMI and the performance subtest of the WASI. There were only significant differences between the symptomatic participants and the control participants; the asymptomatic carriers had scores relatively close to those of the control participants. The median standardized scores of the VMI and the WASI Performance IQ for the symptomatic participants were 70 [(58-85); n=4) and 101 [(76-131); n=21], respectively, compared with the control participants, who had median scores of 95 [(73-107); n=21, p=0.002] and 120 [(95-138); n=21, p<0.0001], respectively. (Table 3)

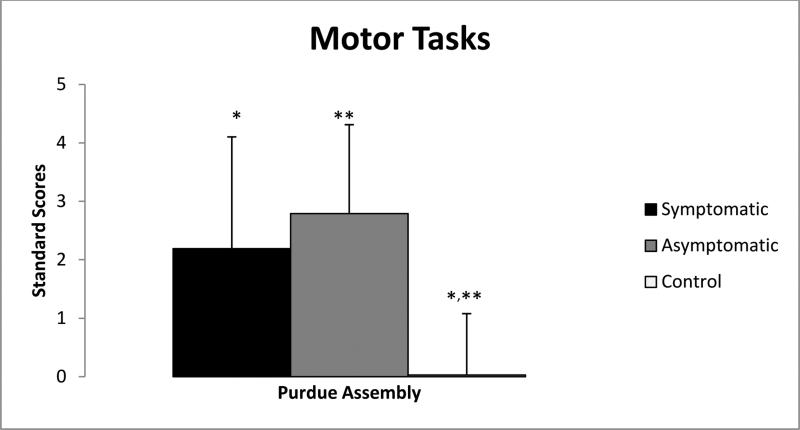

Motor ability was assessed with the Purdue Assembly task. The Purdue assembly showed significant differences among participant groups. The asymptomatic carrier participants [−3.31 (−3.96 - −0.56); n=5] performed very similarly to the symptomatic participants [−1.91(−4.63- −0.22); n= 4] with comparable median scores. However, the control participants’ median score was −0.31 [(−1.92 – 1.48); n=20], which was significantly different from asymptomatic carrier participants (p=0.04) and symptomatic participants (p=0.01) (Figure 3, Table 3).

Figure 3.

Significant differences between participant groups performance on the Purdue Pegboard, a test of fine motor ability.

Language ability was determined with the PPVT, EVT, and WJ-III oral comprehension subtest. There were no significant differences between groups. (Table 3)

Academic ability was evaluated using the calculation and passage comprehension subtests of the WJ-III and the Full IQ of the WASI. The Full IQ of the WASI demonstrated significant differences between the symptomatic participants’ performance and control participants’ performances. Asymptomatic carriers median full IQ score value was 111 [(100-125); n=16]. The median of the symptomatic participants’ scores was, 101 [(78-134); n=21, p=0.004), which was significantly different from the median of the control participants, 124 [(92-140); n=31, p=0.005). The Calculation subtest of the WJ-III exhibited a significant difference between the median of the symptomatic participants’ scores 81 [(112-75); n=4], and control participants’ scores, 118 [(80-144); n=20, p=0.001]. Passage Comprehension, similar to calculation, showed a significant difference between the symptomatic participants’ scores, 97 [(92-100); n=4], and the control participants’ scores, 114 [(96-133); n=20, p=0.004) (Table 3).

4. Discussion

The discovery that “asymptomatic” female carriers of OTCD demonstrate cognitive deficits compared to the normative population helped to elucidate the many areas of the brain that are sensitive to HA, even in the absence of a clinically recognizable HA2. Batshaw 2 discovered that when compared with protein tolerant siblings, female carriers were lower in performance and full scale IQ to a significant degree. Gyato 3 also studied asymptomatic female carriers and found, similar to Batshaw2, that they struggled with motor dexterity and performance measures.

The goal of this study was to determine the sensitivity of a selective cognitive battery on identifying neurocognitive deficits in asymptomatic carriers of OTCD. The asymptomatic carriers performed similar to the age matched control group in many of the assessments, specifically in language, academic and simple attention. These data support the work of Gyato 3 and Batshaw 2 that asymptomatic carriers tend to perform as well as control participants in measures of simple attention and verbal skills.

In concordance with Gyato3, our study found that the fine motor task elicited significant differences between control participant performance and asymptomatic carriers and symptomatic participant performance. Interestingly, our study also highlighted cognitive deficits in the asymptomatic patients that may not have previously been recognized. The Stroop task demonstrated highly significant differences between control participant performance and asymptomatic carrier performance when incongruent reaction time was compared with congruent reaction time. We hypothesize that asymptomatic participants only demonstrate cognitive deficits in executive function and motor tasks when challenged. This has also been observed in fMRI studies evoking working memory task of increasing difficulty19.

Recently, more targeted studies have evaluated the extent of the neurological damage caused by hyperammonemic episodes and the regions of the brain that are most sensitive to these effects19. Our recent imaging study found that white matter in the frontal lobe is predominantly affected during hyperammonemic episodes in OTCD patients21, adding to our understanding of executive dysfunction in OTCD patients.

Despite OTCD being the most common of the urea cycle disorders, it is still relatively rare, limiting the sample size of the study. Many of the cognitive tasks showed trends with symptomatic patients attaining the lowest score, asymptomatic patients with the intermediate scores and the controls scoring the highest. Therefore, it may be that asymptomatic patients actually have slight cognitive deficits in many areas, but we only had the statistical power to detect the most severe. Furthermore, this was a cross-sectional study conducted over seven years therefore tasks were updated and changed, so not everyone performed the same cognitive battery. We recruited patients with IQ's ≥80 and at baseline health, thus selecting for higher functioning participants.

5. Conclusions

Asymptomatic carriers and symptomatic patients demonstrated no significant differences in measures of simple attention,language and verbal memory. However, when cognitively challenged with tasks measuring executive function, fine motor ability, cognitive flexibility and inhibition ability, they demonstrate deficits. This suggests that cognitive dysfunction is best measurable in asymptomatic carriers and symptomatic participants when cognitively challenged.

Research Highlights.

Children and Adult carriers of Ornithine Transcarbamylase Deficiency also show cognitive deficits compared to normal control participants when cognitively challenged

Furthermore, carriers struggled particularly with fine motor tasks and measure of executive function.

This data may lead to future research that will elucidate the specific brain regions affected by hyperammonemic episodes.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by 5U54HD061221. We also appreciate the support of the Intellectual and Development Disorders Research Center (IDDRC) grant: 5P30HD040677-13. Thank you to all participants for taking part in our study, to all referring doctors and the National Urea Cycle Disorder Foundation.

Abbreviations

- UCD

Urea Cycle Disorder

- OTCD

Ornithine Transcarbamylase Deficiency

- CTMT

Comprehensive Trail Making Test

- WASI

Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence

- ANCOVA

Analysis of Covariance

- WIS

Wechsler Scale of Intelligence

- BRIEF

Behavior Rating Inventory for Executive Function

- WJ – III

Woodcock-Johnson Intelligence Scale

- VMI

Beery-Buktenica Developmental Test of Visual-Motor Integration

- PPVT-III

Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test – Third Edition

- EVT

Expressive Vocabulary Test

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Brusilow SW, Maestri NE. Urea cycle disorders: diagnosis, pathophysiology, and therapy. Adv Pediatr. 1996;43:127–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Batshaw ML, Roan Y, Jung AL, Rosenberg LA, Brusilow SW. Cerebral dysfunction in asymptomatic carriers of ornithine transcarbamylase deficiency. N Engl J Med. 1980;302:482–5. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198002283020902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gyato K, Wray J, Huang ZJ, Yudkoff M, Batshaw ML. Metabolic and neuropsychological phenotype in women heterozygous for ornithine transcarbamylase deficiency. Ann Neurol. 2004;55:80–6. doi: 10.1002/ana.10794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Maestri NE, Brusilow SW, Clissold DB, Bassett SS. Long-term treatment of girls with ornithine transcarbamylase deficiency. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:855–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199609193351204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nicolaides P, Liebsch D, Dale N, Leonard J, Surtees R. Neurological outcome of patients with ornithine carbamoyltransferase deficiency. Arch Dis Child. 2002;86:54–6. doi: 10.1136/adc.86.1.54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nagata N, Matsuda I, Matsuura T, Oyanagi K, Tada K, Narisawa K, Kitagawa T, Sakiyama T, Yamashita F, Yoshino M. Retrospective survey of urea cycle disorders: Part 2. Neurological outcome in forty-nine Japanese patients with urea cycle enzymopathies. Am J Med Genet. 1991;40:477–81. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320400421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kido J, Nakamura K, Mitsubuchi H, Ohura T, Takayanagi M, Matsuo M, Yoshino M, Shigematsu Y, Yorifuji T, Kasahara M, Horkawa R, Endo F. Long-term outcome and intervention of urea cycle disorders in Japan. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2012;35:777–85. doi: 10.1007/s10545-011-9427-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cohen JD, Dunbar K, McClelland JL. On the control of automatic processes: A parallel distributed processing account of the Stroop effect. Psychological Review. 1990;97:332–361. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.97.3.332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Smith SR, Seversca AM, Edwards JW, Rahban R, Barazani S, Nowinski LA, Little JA, Blazer AL, Green JG. Exploring the validity of the comprehensive trail making test. Clin Neuropsychol. 2008;22:507–18. doi: 10.1080/13854040701399269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Roth RM, Lance CE, Isquith PK, Fischer AS, Giancola PR. Confirmatory factor analysis of the behavior rating inventory of executive function-adult version in healthy adults and application to attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Arch Clin Neuropsychol. 2013;28:425–34. doi: 10.1093/arclin/act031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Whitmyre JW, Pishkin V. The abbreviated Wechsler adult intelligence scale in a psychiatric population. J Clin Psychol. 1958;14:189–91. doi: 10.1002/1097-4679(195804)14:2<189::aid-jclp2270140225>3.0.co;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wechsler D. Manual for the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale. Pearson; San Antonio, TX: 2008. p. 4. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Preda C. Test of visual-motor integration: construct validity in a comparison with the Beery-Buktenica Developmental Test of Visual-Motor Integration. Percept Mot Skills. 1997;84:1439–43. doi: 10.2466/pms.1997.84.3c.1439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tiffin J, Asher EJ. The Purdue pegboard; norms and studies of reliability and validity. J Appl Psychol. 1948;32:234–47. doi: 10.1037/h0061266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dunn LM, Hottel JV. Peabody picture vocabulary test performance of trainable mentally retarded children. Am J Ment Defic. 1961;65:448–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Smith A. Development and course of receptive and expressive vocabulary from infancy to old age: administrations of the Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test, Third Edition, and the Expressive Vocabulary Test to the same standardization population of 2725 subjects. Int J Neurosci. 1997;92:73–8. doi: 10.3109/00207459708986391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Benson N, Taub GE. Invariance of Woodcock-Johnson III scores for students with learning disorders and students without learning disorders. Sch Psychol Q. 2013;28:256–72. doi: 10.1037/spq0000028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brown MB, Giandenoto MJ, Bolen LM. Diagnosing written language disabilities using the Woodcock-Johnson Tests of Educational Achievement-Revised and the Wechsler Individual Achievement Test. Psychol Rep. 2000;87:197–204. doi: 10.2466/pr0.2000.87.1.197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gropman AL, Shattuck K, Prust MJ, Seltzer RR, Breeden AL, Hailu A, Rigas A, Hussain R, VanMeter J. Altered neural activation in ornithine transcarbamylase deficiency during executive cognition: an fMRI study. Hum Brain Mapp. 2013;34:753–61. doi: 10.1002/hbm.21470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Msall M, Monahan PS, Chapanis N, Batshaw ML. Cognitive development in children with inborn errors of urea synthesis. Acta Paediatr Jpn. 1988;30:435–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-200x.1988.tb02534.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gropman AL, Gertz B, Shattuck K, Kahn IL, Seltzer R, Krivitsky L, Van Meter J. Diffusion tensor imaging detects areas of abnormal white matter microstructure in patients with partial ornithine transcarbamylase deficiency. AJNR. 2010;31:1719–1723. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A2122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]