Abstract

Objective

Total pregnancy weight gain has been associated with infant birthweight; however, most prior studies lacked repeat ultrasound measurements. Understanding of the longitudinal changes in maternal weight gain and intrauterine changes in fetal anthropometrics is limited.

Study design

Prospective data from 1314 Scandinavian singleton pregnancies at high-risk for delivering small-for-gestational-age (SGA) were analyzed. Women had ≥1 (median 12) antenatal weight measurements. Ultrasounds were targeted at17, 25, 33, and 37 weeks of gestation. Analyses involved a multi-step process. First, trajectories were estimated across gestation for maternal weight gain and fetal biometrics [abdominal circumference (AC, mm), biparietal diameter (BPD, mm), femur length (FL, mm), and estimated fetal weight (EFW, grams)] using linear mixed models. Second, the association between maternal weight changes (per 5kg) and corresponding fetal growth from 0–17, 17–28, and 28–37 weeks was estimated for each fetal parameter adjusting for prepregnancy body mass index, height, parity, chronic diseases, age, smoking, fetal sex, and weight gain up to the respective period as applicable. Third, the probability of fetal SGA, EFW <10th percentile, at the 3rd ultrasound was estimated across the spectrum of maternal weight gain rate by SGA status at the 2nd ultrasound.

Results

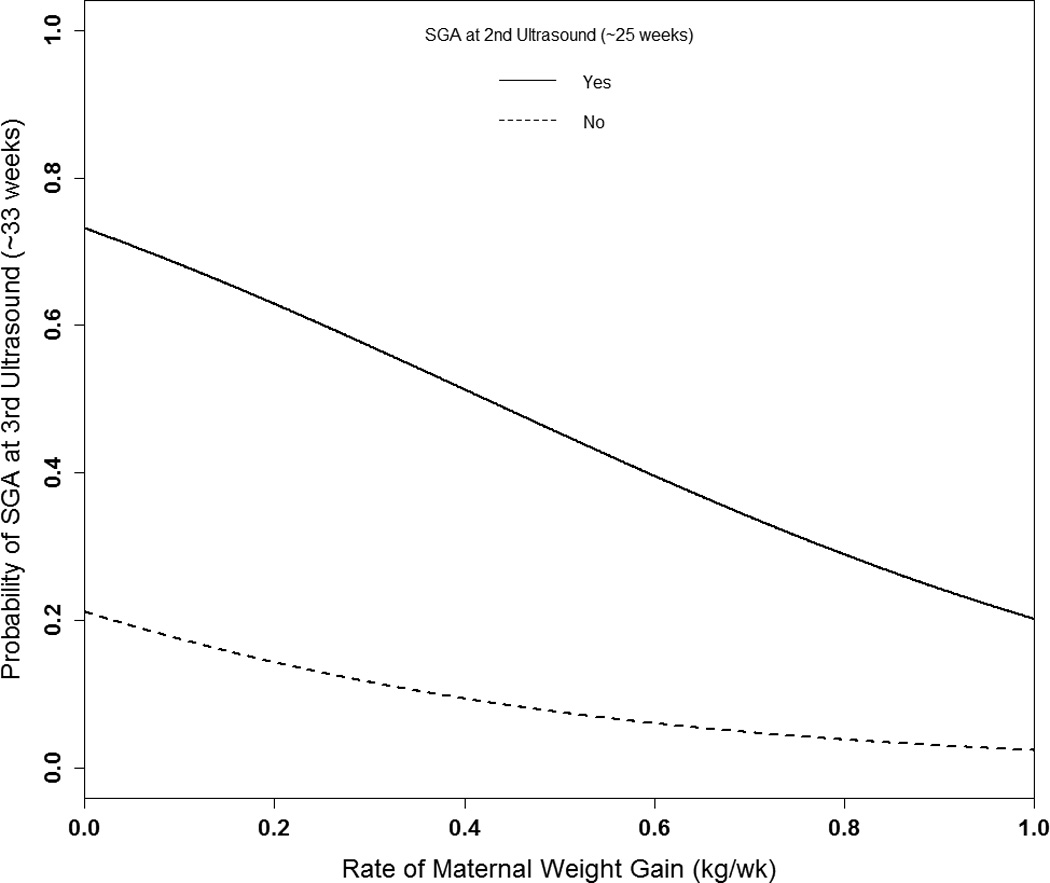

From 0–17 weeks, changes in maternal weight were most strongly associated with changes in BPD [β=0.51 per 5kg (95%CI 0.26, 0.76)] and FL [β=0.46 per 5kg (95%CI 0.26, 0.65)]. From 17–28 weeks, AC [β=2.92 per 5kg (95%CI 1.62, 4.22)] and EFW [β=58.7 per 5kg (95%CI 29.5, 88.0)] were more strongly associated with changes in maternal weight. Increased maternal weight gain was significantly associated with a reduced probability of intrauterine SGA; for a normal weight woman with SGA at the 2nd ultrasound, the probability of fetal SGA with a weight gain rate of 0.29kg/w (10th percentile) was 59%, compared to 38% with a rate of 0.67kg/w (90th percentile).

Conclusion

Among women at high-risk for SGA, maternal weight gain was associated with fetal growth throughout pregnancy, but had a differential relationship with specific biometrics across gestation. For women with fetal SGA identified mid-pregnancy, increased antenatal weight gain was associated with a decreased probability of fetal SGA approximately 7 weeks later.

Keywords: Fetal growth, Growth restriction, Small-for-gestational-age, Weight gain

INTRODUCTION

Gestational weight gain represents the accumulation of maternal, fetal, and placental tissue throughout pregnancy and maternal fluid expansion. The Institute of Medicine (IOM) provides weight gain recommendations with the intention of optimizing maternal and neonatal outcomes.[1] Birthweight, was a primary outcome studied when defining the recommendations, as it is predictive of neonatal and long-term morbidities.[1] Gaining less or greater than recommended increases the risk for neonatal small-for-gestational-age (SGA) or large-for-gestational-age (LGA) birthweight, respectively.[2]There may be advantages of using intrauterine fetal growth instead of birthweight. Assessing the relationship between maternal weight gain and fetal biometrics, may aid in better understanding the mechanism by which maternal weight impacts growth and in identifying timeframes for interventions. Also, most prior research related to fetal growth was limited to total weight gain,[3] which limits detection of critical periods where maternal weight may be more or less important for fetal growth, [4–6] and has methodological limitations.[7] Previous longitudinal gestational weight gain and intrauterine fetal growth studies have been limited by small sample sizes,[8, 9] did not examine the changing dynamics between weight gain and fetal growth across gestation,[9] or only examined longitudinal linear growth.7

Our objective was to characterize the association between maternal weight gain and fetal growth across gestation in a prospective cohort study with longitudinal measures of antenatal weight gain and fetal growth including femur length (FL), abdominal circumference (AC), biparietal diameter (BPD) and estimated fetal weight (EFW). We also assess the importance of maternal weight change for fetal SGA after detection mid-gestation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The NICHD Study of Successive Small-for-Gestational-Age Births was a prospective cohort study conducted in Norway and Sweden (1986–1988).[10] Eligible women were parity 1 or 2, Caucasian, spoke a Scandinavian language, had a singleton gestation, and were <20 weeks of gestation by enrollment (n=5722). The original cohort design included two groups of women. First, a 10% random sample of women were enrolled to be representative of the underlying source population (n=561). Second, women who were identified as having an elevated risk for delivering an SGA neonate based on the following were enrolled: prior low birthweight infant (n=462; 33.4%) or perinatal death (n=85; 6.1%), smoking at conception (n=955; 69.0%), chronic renal disease or hypertension (n=39; 2.8%), and/or a prepregnancy weight <50 kg (n=306; 22.1%) (n=1384). By design of the original protocol, the remaining non-high-risk women were not enrolled in the study. All participants provided signed informed consent and institutional review board approval was obtained.

We limited the current analysis to high-risk women with data on, height, ≥1 antenatal weight measurement, ≥1 fetal ultrasound, and relevant covariates, describe below (n=1314). The women in the final sample were more likely (69.5%) to be primiparous than excluded women (55.9%) (P=0.01). No other meaningful or significant differences were observed in prepregnancy weight, height, age, smoking, chronic diseases, fetal sex or gestational age at delivery between the final and excluded sample (n=70; 5.0%) (data not shown).

Antenatal visits were targeted at 17 (95% ±2), 25 (95% ±1), 33 (95% ±1), and 37 (95% ±1) weeks. Gestational age was calculated based on last menstrual period (LMP) and confirmed ±14 days by second trimester ultrasound. The ultrasound estimate was used if discrepant with LMP or LMP was missing (n=260; 18.8%).[10] At enrollment, women reported smoking at conception, chronic diseases including renal disease, chronic hypertension, heart disease or diabetes, and their prepregnancy weight and height. Parity was defined as the number of previous births ≥20 weeks. Women were instructed to bring their personal health record to each study visit. This record contained women’s weight recorded at each prenatal visit by her regular health care provider and at hospital admission for delivery. Study midwives extracted the weight and date of each measurement (median 11, max 21).

The fetal ultrasound measures obtained at each study visit included BPD (mm), middle abdominal diameter (mm), and FL (mm). The AC (mm) was calculated as 3.1416*(middle abdominal diameter). The Hadlock formula was used to calculate EFW (g).[11] Intrauterine SGA was defined as EFW<10th percentile of the random 10% of the study sample (n=561) to be representative of the source population. Fetal sex was reported from the newborn’s medical exam.

Longitudinal associations between maternal weight gain and fetal growth (AC, BPD, FL, and EFW) were analyzed using a multi-stage approach. First, individual trajectories across gestation of weight gain and fetal growth were estimated using linear mixed models.[12] This approach allowed for the estimation of overall trajectories and individual’s trajectories. Second, we used individual’s trajectories to calculate each individual’s weight and fetal growth at 17, 28 and 37 weeks, this accounted for the different number of weight measurements and the variation in study visit days between women.

Prepregnancy weight was obtained by extrapolation from the maternal weight linear mixed model in order to correct for potential errors in self-reported weight and account for missing values (n=6). Prepregnancy body mass index (BMI, kg/m2) was calculated and categorized: underweight (BMI<18.5), normal weight (18.5–24.9), overweight (25.0–29.9), or obese (≥30.0).[13] Due to the limited number of obese women (n=32), overweight and obese were combined.

We computed Pearson correlations between changes in maternal weight and fetal size between early- (0–17 weeks), mid- (17–28 weeks), and late-pregnancy (28–37 weeks). We used linear regression to estimate the association between weight gain and fetal growth for each period adjusting for maternal age, prepregnancy BMI, height, parity, chronic diseases, smoking, and fetal sex. Mid- and late-pregnancy models were also adjusted for maternal weight gain up to the start of the respective period. We tested for multiplicative interactions between each of the covariates and maternal weight change.

We assessed the impact of maternal weight gain on fetal SGA, an important clinical endpoint. For this analysis, subjects had to have EFW estimated at both the 2nd and 3rd ultrasound (n=972). Logistic regression was used to estimate the probability of 3rd ultrasound fetal SGA across the spectrum of maternal weight gain rate between ultrasounds and tested for an interaction between 2nd ultrasound fetal SGA and maternal weight gain. Goodness of fit tests and spline analyses confirmed that the logistic regression model with a linear term for weight gain rate fit well.

SAS version 9.4 (Cary, NC, USA) and R version 3.0.2 (Vienna, Austria) were used and P-values <0.05 were considered significant.

RESULTS

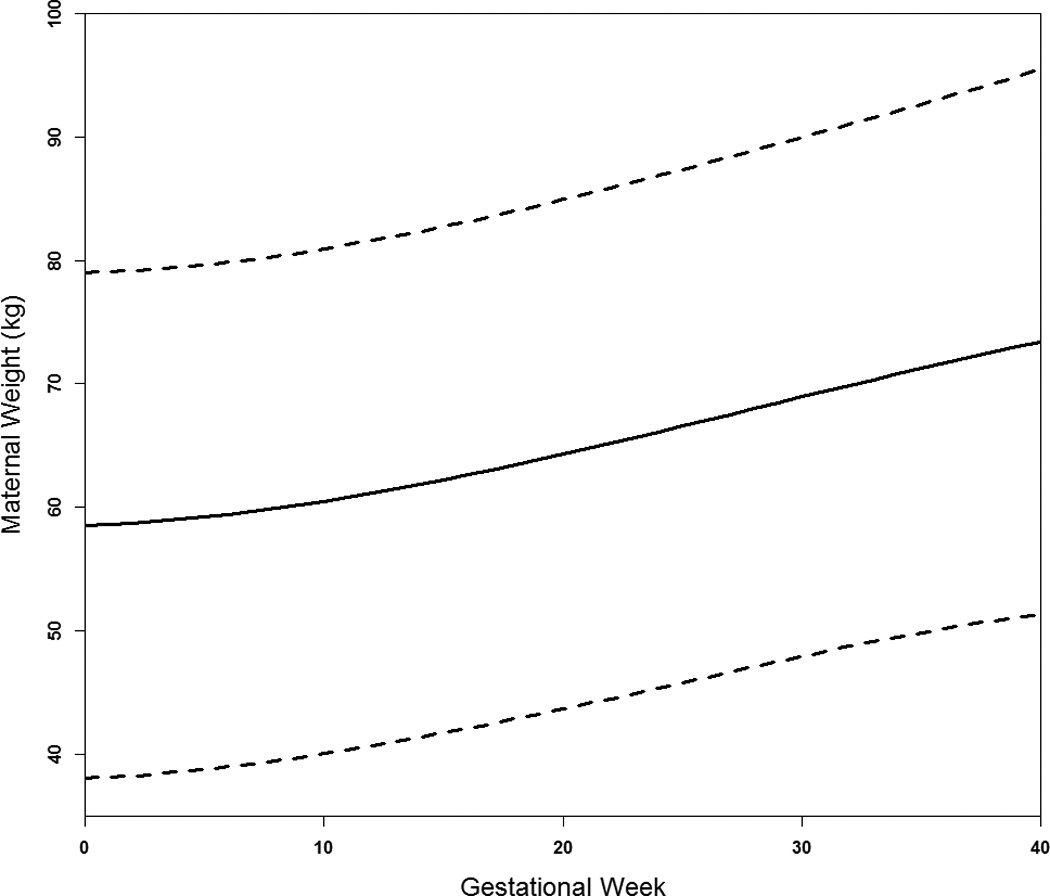

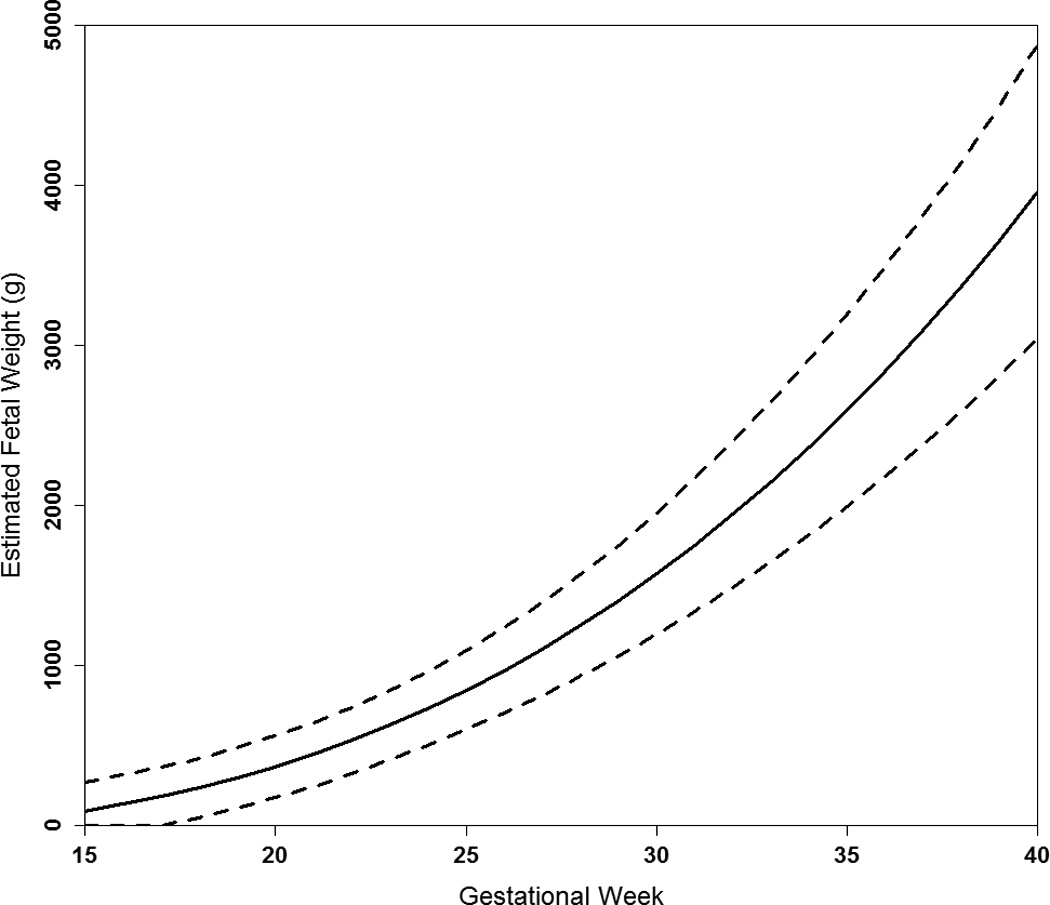

Women were on average 29 years of age and all were parous with 30.8% having had two prior births (Table 1). Many women smoked at conception (69%), of which 88% and 81% continued into the 2nd and 3rd trimesters, respectively. Maternal weight gain increased across gestation (Figure 1) for an average total gain of 15.0 kg (standard deviation [SD] 4.7). The large variations in percentiles reflect in part prepregnancy weight variation. Weight gain differed by prepregnancy BMI (P<0.001) with overweight/obese women gaining the lowest rate during the 2nd and 3rd trimester (0.40 kg/wk; SD 0.18); however, there was no difference between underweight (0.45 kg/wk; SD 0.14) and normal weight women (0.47 kg/wk; SD 0.14) (P=0.25). As expected, fetal growth rate increased with increasing gestation (Figure 2).

TABLE 1.

Sample characteristics.

| Mean n (%) |

(SD) or (n=1314) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Age, y | 28.6 | (4.6) |

| 17–24 | 250 | (19.0) |

| 25–29 | 554 | (42.2) |

| 30–34 | 351 | (26.7) |

| 35–41 | 159 | (12.1) |

| Height, cm | 165.3 | (5.9) |

| Prepregnancy weight, kg | 58.5 | (10.4) |

| Prepregnancy BMI, kg/m2 | 21.4 | (4.2) |

| <18.5 | 222 | (25.0) |

| 18.5–24.9 | 937 | (57.8) |

| 25.0–29.9 | 123 | (12.9) |

| ≥ 30.0 | 32 | (4.3) |

| Weight gain, kg | ||

| 0–17 wks | 4.5 | (2.1) |

| 0–28 wks | 9.5 | (3.3) |

| 0–37 wks | 13.6 | (4.3) |

| Totala | 14.6 | (4.8) |

| Weight gain adequacy, 2nd/3rd trimesterb | ||

| Inadequate | 323 | (24.6) |

| Adequate | 507 | (38.6) |

| Excessive | 484 | (36.8) |

| Parity | ||

| 1 | 913 | (69.5) |

| 2 | 401 | (30.5) |

| Prepregnancy smoking | 910 | (69.3) |

| Prepregnancy chronic diseasesc | 40 | (3.0) |

| Gestational age at delivery, wks | 39.5 | 2.3 |

| 20–<28 | 11 | (0.8) |

| 28–<34 | 18 | (1.4) |

| 34–<37 | 71 | (5.4) |

| ≥37 | 1214 | (92.4) |

| Male fetal sex | 668 | (50.8) |

| Biaparietal diameter, mm | ||

| 17 wks | 39.1 | (2.0) |

| 28 wks | 73.1 | (2.7) |

| 37 wks | 92.6 | (3.0) |

| Femur length, mm | ||

| 17 wks | 24.1 | (1.5) |

| 28 wks | 53.6 | (1.8) |

| 37 wks | 70.7 | (1.8) |

| Abdominal circumference, mm | ||

| 17 wks | 116.4 | (4.8) |

| 28 wks | 236.4 | (8.8) |

| 37 wks | 327.4 | (14.4) |

| Estimated fetal weight, g | ||

| 17 wks | 177.2 | (9.9) |

| 28 wks | 1247.0 | (118.7) |

| 37 wks | 3096.6 | (318.2) |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index.

Total weight gain calculated as the weight at delivery minus prepregnancy weight.

Weight gain adequacy defined according to the 2009 Institute of Medicine Recommendations for 2nd and 3rd trimester rate of weight gain: underweight, 0.44–0.58 kg/wk; normal weight, 0.35–0.50 kg/wk; overweight, 0.23–0.33 kg/wk; obese, 0.17–0.27 kg/wk.

Prepregnancy chronic diseases includes renal disease, heart disease, type I diabetes, type II diabetes, and chronic hypertension.

Figure 1.

Average trajectory of maternal weight across gestation (50th percentile solid line) with the 10th and 90th percentiles (dashed lines).

Figure 2.

Average trajectory of average estimated fetal weight across gestation (50th percentile solid line) with the 10th and 90th percentiles (dashed lines).

Throughout pregnancy the unadjusted correlation between maternal weight gain and fetal growth tended to be weakest for FL and strongest for AC and EFW (Table 2). The strength of the association between maternal weight gain and BPD was fairly consistent across pregnancy with every 5 kg increase in weight gain associated with BPD increases of 0.5 mm (range 0.44 to 0.51).

TABLE 2.

Unadjusted and adjusted association between changes in maternal weight across pregnancy and fetal growth.

| Biparietal Diameter (mm) per 5 kg Maternal Weight |

Femur Length (mm) per 5 kg Maternal Weight |

Abdominal Circumference (mm) per 5 kg Maternal Weight |

Estimated Fetal Weight (g) per 5 kg Maternal Weight |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| r | β (95% CI) | r | β (95% CI) | r | β (95% CI) | r | β (95% CI) | |||||

| Early, 0 to 17 weeks, (n=1314)a | ||||||||||||

| Unadjusted | 0.13 | 0.59 | (0.34, 0.84) | 0.14 | 0.49 | (0.30, 0.68) | 0.16 | 1.75 | (1.16, 2.35) | 0.19 | 4.31 | (3.08, 5.53) |

| Adjustedb | 0.25 | 0.51 | (0.26, 0.76) | 0.19 | 0.46 | (0.26, 0.65) | 0.22 | 1.69 | (1.08, 2.29) | 0.26 | 4.21 | (2.98, 5.45) |

| Mid, 17 to 28 weeks, (n=1303) | ||||||||||||

| Unadjusted | 0.15 | 0.54 | (0.35, 0.73) | 0.12 | 0.23 | (0.13, 0.33) | 0.20 | 3.43 | (2.49, 4.36) | 0.20 | 79.6 | (58.7, 100.5) |

| Adjustedb,c | 0.32 | 0.43 | (0.17, 0.69) | 0.23 | 0.15 | (0.01, 0.29) | 0.31 | 2.92 | (1.62, 4.22) | 0.30 | 58.7 | (29.5, 88.0) |

| Late, 28 to 37 weeks, (n=1214) | ||||||||||||

| Unadjusted | 0.12 | 0.49 | (0.26, 0.72) | 0.07 | 0.17 | (0.04, 0.30) | 0.17 | 3.48 | (2.37, 4.58) | 0.16 | 95.3 | (62.9, 127.8) |

| Adjustedb,d | 0.24 | 0.46 | (0.20, 0.72) | 0.18 | 0.22 | (0.07, 0.37) | 0.32 | 2.86 | (1.63, 4.08) | 0.31 | 52.5 | (16.6, 88.4) |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; r, Pearson correlation coefficient

Changes in sample sizes reflect early deliveries.

Models adjusted for maternal age, prepregnancy body mass index, height, parity, smoking, chronic diseases (renal disease, heart disease, type I diabetes, type II diabetes, and chronic hypertension), and fetal sex.

Models adjusted for maternal weight gained from 0–17 weeks.

Models adjusted for maternal weight gained from 0–28 weeks.

Maternal weight gain was most strongly associated with FL early in pregnancy, with FL increasing by 0.46 mm [95% confidence interval (CI) 0.26, 0.65] for every 5 kg increase in maternal weight, but by only 0.22 mm (95% CI 0.07, 0.37) late in pregnancy (Table 2). There was a small, but significant association between maternal weight gain and fetal AC and EFW early in pregnancy; the association peaked mid-pregnancy, such that for every 5 kg increase in maternal weight, fetal AC increased by 2.92 mm (95% CI 1.62, 4.22) and EFW by 58.7 g (95% CI 29.5, 88.4); late pregnancy was not meaningfully or significantly different from mid-pregnancy.

A significant interaction was detected between maternal weight and prepregnancy BMI status for FL (P=0.03), AC (P=0.04, P=0.003) and EFW (P=0.03, P=0.008) early- and mid-pregnancy, respectively, indicating that the strength of the association differed according to prepregnancy weight status. No significant interaction was detected for BPD. Stratified results are presented in Table 3 for FL, AC and EFW. Early in pregnancy, the association between weight gain and FL, AC and EFW was attenuated with increasing BMI. The association between weight gain and AC was stronger among underweight than normal weight women with AC increasing by 3.00 mm (95% CI 1.23, 4.78) and 1.79 mm (95% CI 1.05, 2.52), respectively, per 5 kg increase in maternal weight. Mid-pregnancy there was no meaningful association among underweight or overweight mothers.

TABLE 3.

Adjusted association between changes in maternal weight across pregnancy and fetal growth stratified by prepregnancy body mass index status.

| Femur Length (mm) per 5 kg Maternal Weight |

Abdominal Circumference (mm) per 5 kg Maternal Weight |

Estimated Fetal Weight (g) per 5 kg Maternal Weight |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| r | β (95% CI) | r | β (95% CI) | r | β (95% CI) | ||||

| Early, 0 to 17 weeks, (n=1314)a,b | |||||||||

| BMI <18.5 (n=222) | 0.34 | 0.84 | (0.27, 1.41)* | 0.36 | 3.00 | (1.23, 4.78)* | 0.42 | 7.22 | (3.81, 10.63)* |

| BMI 18.5–24.9 (n=937) | 0.19 | 0.52 | (0.28, 0.74) | 0.23 | 1.79 | (1.05, 2.52) | 0.25 | 4.46 | (2.92, 5.99) |

| BMI ≥25.0 (n=155) | 0.28 | 0.13 | (−0.32, 0.58) | 0.26 | 0.97 | (−0.44, 2.37) | 0.29 | 2.16 | (−0.56, 4.88) |

| Mid, 17 to 28 weeks, (n=1303)a,b,c | |||||||||

| BMI <18.5 (n=219) | 0.35 | 0.07 | (−0.27, 0.42) | 0.46 | 0.99 | (−2.06, 4.03)* | 0.46 | 8.19 | (−60.9, 77.3)* |

| BMI 18.5–24.9 (n=929) | 0.24 | 0.24 | (0.06, 0.41) | 0.30 | 4.13 | (2.53, 5.74) | 0.30 | 85.3 | (49.1, 121.6) |

| BMI ≥25.0 (n=155) | 0.29 | −0.09 | (−0.44, 0.25) | 0.31 | −0.48 | (−3.60, 2.64) | 0.32 | −10.9 | (−79.0, 57.1) |

| Late, 28 to 37 weeks, (n=1214)a,b,d | |||||||||

| BMI <18.5 (n=201) | 0.30 | 0.43 | (0.00, 0.86) | 0.48 | 1.72 | (−1.23, 4.72) | 0.47 | −27.7 | (−120.6, 65.2) |

| BMI 18.5–24.9 (n=864) | 0.16 | 0.24 | (0.06, 0.42) | 0.30 | 3.44 | (1.94, 4.93) | 0.31 | 75.6 | (31.5, 119.7) |

| BMI ≥25.0 (n=149) | 0.34 | 0.07 | (−0.31, 0.46) | 0.32 | 1.93 | (−1.07, 4.94) | 0.31 | 8.69 | (−73.9, 91.3) |

Abbreviations: BMI, prepregnancy body mass index (kg/m2); CI, confidence interval; r, Pearson correlation coefficient

Changes in sample sizes reflect early deliveries.

Models adjusted for maternal age, prepregnancy body mass index, height, parity, smoking, chronic diseases (renal disease, heart disease, type I diabetes, type II diabetes, and chronic hypertension), and fetal sex.

Models adjusted for maternal weight gained from 0–17 weeks.

Models adjusted for maternal weight gained from 0–28 weeks.

Weight gain by prepregnancy BMI status interaction P<0.05.

Lastly, we assessed the importance of maternal weight change on the probability of persistent fetal SGA. At the 2nd ultrasound, approximately 25 weeks, 129 (13.3%) fetuses were SGA. At the 3rd ultrasound, approximately 33 weeks, 137 (14.1%) fetuses were SGA, of whom 63 (46.0%) were persistent cases and 74 (54.0%) were new cases, representing late-onset SGA. On average women gained 3.8 kg (SD 1.3) between ultrasounds, for a rate of 0.48 kg/w (SD 0.15). As weight gain increased, the probability of 3rd ultrasound SGA decreased (P=0.002) (Figure 3). There was no interaction between maternal weight gain and prepregnancy BMI (P=0.73) nor 2nd ultrasound SGA (P=0.33), but the baseline SGA risk differed by 2nd ultrasound status, as reflected in the large difference in probabilities between the two lines. For the average woman in the study, the probability of persistent SGA with a weight gain rate of 0.29 kg/w (10th percentile) was 58%, compared to 50% with a rate of 0.42 kg (the midpoint of the recommended 2nd/3rd trimester rate for normal weight women), but only 36% with a rate of 0.67 kg/w (90th percentile).The probability of late-onset SGA decreased from 12% to 5% from a rate weight gain from 0.29 to 0.67 kg/w.

Figure 3.

Probability of fetal SGA at the 3rd ultrasound (~33 weeks) according to maternal rate of weight gain by SGA status at 2nd ultrasound (~25 weeks).

Logit (Probability SGA3rd=1) = [−1.314 + −2.376*(weight gain rate) +2.316*(SGA2nd) + 0.296*(parity=1) + −0.016*(height from 165.5 cm) + −0.092*(prepregnancy BMI from 21.2 kg/m2) + −0.054*(age from 28.4 years) + −0.198*(smoked) + 1.263*(chronic diseases) + −0.130*(male fetal sex)].

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; SGA, small-for-gestational-age.

COMMENT

Among women with an elevated SGA risk, maternal weight gain was strongly associated with intrauterine fetal growth throughout pregnancy, but had a differential relationship with specific fetal biometrics and varied by prepregnancy BMI. Early pregnancy maternal weight gain was most important for FL and BPD. By mid-pregnancy the association with FL was diminished and weight gain had the greatest impact on AC. The strength of the AC and EFW associations were unchanged from mid- to late-pregnancy and associations with BPD were consistent across pregnancy. Most importantly, the probability of intrauterine SGA at approximately 33 weeks of gestation was decreased with a higher rate of maternal weight gain.

Two prior studies assessed the relation between maternal weight gain and longitudinal fetal growth. One assessed only linear intrauterine growth and found that second to third trimester weight gain was associated with increased femur and tibia length.[8] We observed that FL was most impacted by maternal weight gain early in pregnancy. Another study found that overall maternal weight gain was associated with increases in AC and abdominal lean mass, but no other fetal biometrics such as FL or BPD.[9] That study is not directly comparable to ours as they did not examine the dynamics of the relationship across gestation;[9] for example, we observed a significant association with AC, but found that the association peaked mid-pregnancy. The AC, an indicator of visceral size, may be the most sensitive to changes in maternal nutritional status.[14, 15] Previous studies have also reported that second trimester weight gain is most associated with increased birthweight.[4–6, 16, 17] Therefore, this study highlights the importance of studying gestational weight gain longitudinally as the timing, not just the overall amount, is important for optimizing fetal growth.

We demonstrated the importance of maternal weight gain mid-gestation for a decreased probability of persistent and late-onset intrauterine SGA. This suggests that among high-risk women with early SGA identification, weight gain within and possibly above recommendations may be important for preventing some SGA subtypes. Notably, our conclusions pertain to SGA defined by EFW, but not necessarily intrauterine growth restriction, which is more likely to include etiologies of placental origin, and may not be as driven by maternal nutritional status.[18, 19]

Maternal weight gain was consistently associated with a BPD throughout pregnancy and did not vary by prepregnancy BMI. This might be an example of prioritization of brain growth and supports the need for more research on maternal weight gain and fetal neurodevelopment.[1, 20] Early and late maternal weight is associated with increased childhood cognitive scores among term deliveries.[21]

There was a significant interaction between prepregnancy BMI and maternal weight gain for FL, AC and EFW. There was suggestion the association with FL, AC and EFW was strongest early in pregnancy for underweight mothers, which is consistent with previous studies reporting the strongest association between first trimester weight gain and birthweight.[6, 16] Underweight women may have energy stores which may necessitate the need for greater weight gain early on. Currently, IOM recommendations early in pregnancy are not differentiated by prepregnancy BMI.[1] Although our sample of underweight women was small, if replicated in another prospective study, first trimester weight gain recommendations may also need to be specific to a woman’s prepregnancy weight.

A few limitations warrant discussion. Our findings may not be generalizable to non-high-risk or obese women. While, there may be other “high-risk” conditions not included in the original study protocol definition, these likely represent a small proportion of women. Also ultrasound quality has likely improved since this study period and that gestational age was confirmed with a 2nd trimester ultrasound, which has an error of ±7–10 days compared to 5–7 days with 1st trimester ultrasound.[22] Due to the small number of underweight and overweight women, the stratified results should be interpreted with caution. Also, prepregnancy weight was based on maternal report at enrollment. However, this reflects the clinical availability of this information and addressed potential errors in this data using each individual woman’s longitudinal trajectory of antenatal weights. This study was unique as repeated measures of antenatal weight gain were available and longitudinal ultrasounds were planned a priori allowing for fetal growth assessment across gestation among pregnancies impacted and not impacted by SGA. Our modeling strategy examined the association between longitudinal trajectories of weight gain and fetal growth using separate linear mixed models. Therefore, we could make inferences at important gestational times even though measurement weeks differed between individuals and processes. This approach accounted for measurement error in both processes and avoided attenuation that can occur when error is not considered.

In this study maternal weight gain early in pregnancy was most important for FL, while changes later in pregnancy were most associated with AC and EFW. BPD was consistently associated with weight gain throughout pregnancy. Furthermore, early weight gain was most important for EFW among underweight women, suggesting there may be a benefit of prepregnancy weight specific first trimester recommendations. Lastly, maternal weight gain mid-pregnancy decreased the probability of persistent fetal SGA, which may be beneficial among certain women with early SGA detection.

Acknowledgments

FINANCIAL SUPPORT: This research was supported by the intramural research program of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, National Institutes of Health.

ABBREVIATIONS

- AC

abdominal circumference

- BMI

body mass index

- BPD

biparietal diameter

- CI

confidence interval

- EFW

estimated fetal weight

- FL

femur length

- IOM

Institute of Medicine

- LMP

last menstrual period

- MAD

middle abdominal diameter

- SGA

small-for-gestational-age

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

LOCATION WHERE STUDY WAS CONDUCTED: Norway and Sweden.

DISCLOSURE: The authors report no conflict of interest.

PRESENTATION OF FINDINGS: Dr. Hinkle presented the findings at the annual meeting of the Society for Epidemiologic Research in Seattle, WA on June 26th, 2014. Dr. Grantz presented the findings at the 2nd International Conference on Fetal Growth in Oxford, UK on October 2, 2014.

REFERNECES

- 1.Weight Gain During Pregnancy: Reexamining the Guidelines. Washington, DC: Institute of Medicine and National Research Council; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Johnson J, Clifton RG, Roberts JM, Myatt L, Hauth JC, Spong CY, et al. Pregnancy outcomes with weight gain above or below the 2009 Institute of Medicine guidelines. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;121:969–975. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31828aea03. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Siega-Riz AM, Viswanathan M, Moos MK, Deierlein A, Mumford S, Knaack J, et al. A systematic review of outcomes of maternal weight gain according to the Institute of Medicine recommendations: birthweight, fetal growth, and postpartum weight retention. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 2009;201:339.e1–339.e14. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2009.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Abrams B, Selvin S. Maternal weight gain pattern and birth weight. Obstet Gynecol. 1995;86:163–169. doi: 10.1016/0029-7844(95)00118-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Galjaard S, Pexsters A, Devlieger R, Guelinckx I, Abdallah Y, Lewis C, et al. The influence of weight gain patterns in pregnancy on fetal growth using cluster analysis in an obese and nonobese population. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2013;21:1416–1422. doi: 10.1002/oby.20348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brown JE, Murtaugh MA, Jacobs DR, Jr, Margellos HC. Variation in newborn size according to pregnancy weight change by trimester. The American journal of clinical nutrition. 2002;76:205–209. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/76.1.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hutcheon JA, Bodnar LM, Joseph KS, Abrams B, Simhan HN, Platt RW. The bias in current measures of gestational weight gain. Paediatric and perinatal epidemiology. 2012;26:109–116. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3016.2011.01254.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Neufeld LM, Haas JD, Grajeda R, Martorell R. Changes in maternal weight from the first to second trimester of pregnancy are associated with fetal growth and infant length at birth. The American journal of clinical nutrition. 2004;79:646–652. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/79.4.646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hure AJ, Collins CE, Giles WB, Paul JW, Smith R. Greater maternal weight gain during pregnancy predicts a large but lean fetal phenotype: a prospective cohort study. Matern Child Health J. 2012;16:1374–1384. doi: 10.1007/s10995-011-0904-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bakketeig LS, Jacobsen G, Hoffman HJ, Lindmark G, Bergsjø P, Molne K, et al. Pre-pregnancy risk factors of small-for-gestational age births among parous women in Scandinavia. Acta obstetricia et gynecologica Scandinavica. 1993;72:273–279. doi: 10.3109/00016349309068037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hadlock FP, Harrist RB, Martinez-Poyer J. In utero analysis of fetal growth: a sonographic weight standard. Radiology. 1991;181:129–133. doi: 10.1148/radiology.181.1.1887021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Macdonald-Wallis C, Lawlor DA, Palmer T, Tilling K. Multivariate multilevel spline models for parallel growth processes: application to weight and mean arterial pressure in pregnancy. Statistics in medicine. 2012;31:3147–3164. doi: 10.1002/sim.5385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Obesity: preventing and managing the global epidemic. Report of a WHO consultation. World Health Organ Tech Rep Ser. 2000;894:i–xii. 1–253. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vrachnis N, Botsis D, Iliodromiti Z. The fetus that is small for gestational age. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2006;1092:304–309. doi: 10.1196/annals.1365.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Blumfield ML, Hure AJ, MacDonald-Wicks LK, Smith R, Simpson SJ, Giles WB, et al. Dietary balance during pregnancy is associated with fetal adiposity and fat distribution. The American journal of clinical nutrition. 2012;96:1032–1041. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.111.033241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Margerison-Zilko CE, Shrimali BP, Eskenazi B, Lahiff M, Lindquist AR, Abrams BF. Trimester of maternal gestational weight gain and offspring body weight at birth and age five. Matern Child Health J. 2012;16:1215–1223. doi: 10.1007/s10995-011-0846-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hickey CA, Cliver SP, McNeal SF, Hoffman HJ, Goldenberg RL. Prenatal weight gain patterns and birth weight among nonobese black and white women. Obstet Gynecol. 1996;88:490–496. doi: 10.1016/0029-7844(96)00262-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hendrix N, Berghella V. Non-Placental Causes of Intrauterine Growth Restriction. Seminars in Perinatology. 2008;32:161–165. doi: 10.1053/j.semperi.2008.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bamberg C, Kalache KD. Prenatal diagnosis of fetal growth restriction. Seminars in fetal & neonatal medicine. 2004;9:387–394. doi: 10.1016/j.siny.2004.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Roza SJ, Steegers EAP, Verburg BO, Jaddoe VWV, Moll HA, Hofman A, et al. What Is Spared by Fetal Brain-Sparing? Fetal Circulatory Redistribution and Behavioral Problems in the General Population. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2008;168:1145–1152. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwn233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gage SH, Lawlor DA, Tilling K, Fraser A. Associations of maternal weight gain in pregnancy with offspring cognition in childhood and adolescence: findings from the avon longitudinal study of parents and children. Am J Epidemiol. 2013;177:402–410. doi: 10.1093/aje/kws239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Committee opinion no 611: method for estimating due date. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;124:863–866. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000454932.15177.be. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]