Abstract

Background:

Chronic amphetamine treatment decreases cocaine consumption in preclinical and human laboratory studies and in clinical trials. Lisdexamfetamine is an amphetamine prodrug in which L-lysine is conjugated to the terminal nitrogen of d-amphetamine. Prodrugs may be advantageous relative to their active metabolites due to slower onsets and longer durations of action; however, lisdexamfetamine treatment’s efficacy in decreasing cocaine consumption is unknown.

Methods:

This study compared lisdexamfetamine and d-amphetamine effects in rhesus monkeys using two behavioral procedures: (1) a cocaine discrimination procedure (training dose = 0.32mg/kg cocaine, i.m.); and (2) a cocaine-versus-food choice self-administration procedure.

Results:

In the cocaine-discrimination procedure, lisdexamfetamine (0.32–3.2mg/kg, i.m.) substituted for cocaine with lower potency, slower onset, and longer duration of action than d-amphetamine (0.032–0.32mg/kg, i.m.). Consistent with the function of lisdexamfetamine as an inactive prodrug for amphetamine, the time course of lisdexamfetamine effects was related to d-amphetamine plasma levels by a counter-clockwise hysteresis loop. In the choice procedure, cocaine (0–0.1mg/kg/injection, i.v.) and food (1g banana-flavored pellets) were concurrently available, and cocaine maintained a dose-dependent increase in cocaine choice under baseline conditions. Treatment for 7 consecutive days with lisdexamfetamine (0.32–3.2mg/kg/day, i.m.) or d-amphetamine (0.032–0.1mg/kg/h, i.v.) produced similar dose-dependent rightward shifts in cocaine dose-effect curves and decreases in preference for 0.032mg/kg/injection cocaine.

Conclusions:

Lisdexamfetamine has a slower onset and longer duration of action than amphetamine but retains amphetamine’s efficacy to reduce the choice of cocaine in rhesus monkeys. These results support further consideration of lisdexamfetamine as an agonist-based medication candidate for cocaine addiction.

Keywords: addiction, cocaine, choice, lisdexamfetamine, rhesus monkey, Lisdexamfetamine effects in rhesus monkeys

Introduction

Cocaine addiction represents a significant and global public health problem for which no Food and Drug Administration–approved pharmacotherapy exists (Pomara et al., 2012). Agonist-based pharmacotherapies are medications that share pharmacodynamic mechanisms of action with the target drug of abuse. This medication approach has shown success in the treatment of opioid addiction (Dole et al., 1966; Kreek et al., 2002; Bell, 2014), and potentially for cocaine addiction (for review, see Grabowski et al., 2004b; Herin et al., 2010; Stoops and Rush, 2013; Negus and Henningfield, 2014). For example, over a decade of preclinical (Negus, 2003; Czoty et al., 2011; Banks et al., 2013b; Thomsen et al., 2013) and human laboratory research (Greenwald et al., 2010; Rush et al., 2010), double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trials (Grabowski et al., 2001; Grabowski et al., 2004a; Mariani et al., 2012) have demonstrated amphetamine treatment’s efficacy to decrease cocaine-maintained behaviors across a broad range of experimental conditions and species. However, broad clinical use and deployment of amphetamine-based pharmacotherapies for cocaine addiction remains hindered by concerns of undesirable effects that include high abuse liability.

In the development of an agonist-based pharmacotherapy for cocaine addiction, there are at least three desirable attributes the compound should possess (Grabowski et al., 2004b; Rothman et al., 2005). First, the compound should have a slow onset of drug effects to reduce the abuse liability of the compound (Balster and Schuster, 1973; Schindler et al., 2009). Second, the compound should also have a prolonged duration of action to limit treatment frequency, stabilize treatment plasma levels, and promote patient compliance associated with medication administration (Kreek et al., 2002). Finally, the compound should have demonstrated therapeutic efficacy for decreasing cocaine-maintained behaviors across a range of experimental and clinical endpoints (Grabowski et al., 2004b; Negus and Henningfield, 2014).

Prodrug formulations of amphetamine may represent a viable approach to achieve these desirable attributes (Huttunen et al., 2011). Lisdexamfetamine (Vyvanse) is a Food and Drug Administration–approved medication for the treatment of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, and a prodrug that requires enzymatic hydrolysis by red blood cells for conversion to the active metabolite d-amphetamine and the amino acid L-lysine (Pennick, 2010). Human laboratory studies found that orally administered lisdexamfetamine produced a slower onset of peak subjective effects (3–4h) compared to d-amphetamine (1.5h; Jasinski and Krishnan, 2009a, 2009b). Consistent with these human results, preclinical studies have also demonstrated that lisdexamfetamine has both a slower onset and a prolonged duration of action of neurochemical and behavioral effects compared to d-amphetamine (Rowley et al., 2012). However, whether lisdexamfetamine treatment might produce an amphetamine-like decrease in cocaine-maintained behaviors remains to be empirically determined.

The aims of the present study were: (1) to characterize the potency and time course of lisdexamfetamine’s cocaine-like behavioral effects in rhesus monkeys using a two-key food-reinforced cocaine discrimination procedure; and (2) to determine lisdexamfetamine treatment efficacy to decrease cocaine self-administration in a nonhuman primate model of cocaine addiction that utilizes a concurrent schedule of cocaine and food pellet availability. Drug addiction has been operationally defined as a choice disorder in which behavior is maladaptively allocated toward the procurement and use of drugs and away from behaviors maintained by alternative non-drug reinforcers (Heyman, 2009; Banks and Negus, 2012; Ahmed et al., 2013). A significant goal of treating cocaine addiction is not only to decrease cocaine-maintained behaviors, but also to increase behaviors maintained by alternative, non-drug reinforcers (Volkow et al., 2004; Vocci, 2007; Banks and Negus, 2012). The use of preclinical choice procedures may facilitate the translation of results to human laboratory studies that also rely almost exclusively on choice procedures (Comer et al., 2008; Haney and Spealman, 2008). We hypothesized that lisdexamfetamine administration would produce a slower onset and longer duration of cocaine-like discriminative stimulus effects than d-amphetamine. Furthermore, we hypothesized that 7 days of lisdexamfetamine treatment would produce an amphetamine-like decrease in cocaine choice.

Methods

Subjects

Studies were conducted in nine adult male rhesus monkeys (Macaca mulatta). Four monkeys were used in the cocaine discrimination procedure and associated pharmacokinetic studies, and these monkeys had a history of primarily monoaminergic compound exposure (Banks et al., 2013c, 2014; Banks, 2014). Each of the other five monkeys had a surgically implanted double-lumen venous catheter (STI Components) and prior cocaine self-administration histories during monoaminergic compound exposure (Banks et al., 2011, 2013b, 2013d, 2014). Monkeys could earn 1g of banana-flavored pellets (Grain-based Precision Primate Pellets; Test Diets) during daily experimental sessions. In addition, monkeys received daily food rations (Lab Diet High Protein Monkey Biscuits; PMI Feeds), and the biscuit ration size was individually determined for each monkey to maintain a healthy body weight. Biscuit rations were delivered in the afternoons after behavioral sessions to minimize the effects of biscuit availability and consumption on food-maintained operant responding. Animals also received fresh fruit 3 or 4 afternoons per week. Water was continuously available in each monkey’s home chamber, which also served as the experimental chamber. A 12h light/dark cycle was in effect (lights on from 0600 to 1800h). Environmental enrichment, consisting of foraging boards, novel treats, and movies, was also provided after behavioral sessions. Facilities were licensed by the United States Department of Agriculture and accredited by the Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care. The Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee approved all experimental protocols.

Apparatus

As described previously (Banks et al., 2011, 2013a, 2013b), each home cage was equipped with a customized operant response panel, which had two response keys that could be transilluminated by red or green stimulus lights, and a pellet dispenser (Med Associates, ENV-203–1 000) that delivered food pellets to a receptacle below the operant panel. In addition, the externalized section of the intravenous catheter for drug self-administration monkeys was routed through a jacket and tether system connected to a fluid swivel (Lomir Biomedical) on the cage roof and then to two safety syringe pumps (Med Associates, PHM-108) located above the cage, one for each lumen of the double-lumen catheter. One self-administration pump was used to deliver contingent cocaine injections through one lumen of the double-lumen catheter. The second pump was used to deliver non-contingent saline or d-amphetamine (0.032–0.1mg/kg/h) infusions through the second lumen and was programmed to deliver 0.1mL injections every 20min from 1200h each day until 1100h the next morning. Catheter patency was periodically evaluated with intravenous ketamine (3mg/kg) administration, and the catheter was considered patent if i.v. ketamine administration produced a loss of muscle tone within 10 s.

Cocaine Discrimination Procedure

Monkeys were trained to discriminate 0.32mg/kg cocaine intramuscularly from saline in a two-key food-reinforced discrimination procedure (Banks et al., 2013c, 2014). Briefly, training sessions were conducted 5 days/week during daily behavioral sessions composed of multiple components. Each component consisted of a 5min response period, during which the right and left response keys were transilluminated red and green, respectively. Monkeys could earn up to 10 pellets by responding under a fixed-ratio (FR) 30 schedule of food presentation. Training components were presented at 2h intervals and usually either saline or 0.32mg/kg cocaine was administered i.m. 15min prior to the start of each component. On some occasions, the saline injection was omitted, and monkeys received no injection before the start of the component. After saline injection or no injection, only responding on the red key produced food, whereas after cocaine injection, only responding on the green key produced food; responding on the inappropriate key reset the response requirement on the correct key. The criteria for accurate discrimination were ≥85% injection-appropriate responding before delivery of the first reinforcer, ≥90% injection-appropriate responding for the entire response component, and response rates ≥0.1 responses per s (sufficient to earn at least one pellet) for all components during 7 of 8 consecutive training sessions.

Time course test sessions were identical to training sessions except: (1) completing the response requirement on either key produced food; and (2) 5min response components began 10, 30, 56, 100, 180, 300, and 560min after drug administration to assess the time course of drug effects. Lisdexamfetamine (0.32–3.2mg/kg, i.m.) and d-amphetamine (0.032–0.32mg/kg, i.m.) were tested up to doses that produced full substitution for the cocaine training dose. Test sessions were conducted at 24h, 48h, and 72h after 3.2mg/kg lisdexamfetamine administration because of the prolonged duration of effects. Test sessions were usually conducted on Tuesdays and Fridays, and training sessions were conducted on other weekdays. Test sessions were conducted only if performance during the previous two training sessions met the criteria for accurate discrimination described above. Drug doses were counterbalanced between monkeys. Effects of each lisdexamfetamine dose were determined twice, whereas effects of d-amphetamine doses were determined once.

Data Analysis

For the cocaine discrimination procedure, the primary dependent measures were: (1) percent cocaine-appropriate responding (%CAR; defined as [number of responses on the cocaine-associated key divided by the total number of responses on both the cocaine- and saline-associated keys]*100); and (2) response rates during each component. These dependent measures were then plotted as a function of time after lisdexamfetamine, d-amphetamine, or saline administration. The %CAR and response rates were analyzed using two-way repeated-measures analyses of variance with lisdexamfetamine or d-amphetamine dose and time as the main fixed effects (Prism 6.0f for Mac, GraphPad). A significant interaction was followed by the post hoc Dunnet’s test for comparison to vehicle (saline) conditions within a given time point.

Plasma Lisdexamfetamine and Amphetamine Analysis

Blood samples (1–2 mLs) were collected in Vacutainer tubes containing 3.0mg of sodium fluoride and 6.0mg sodium ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid before;10, 30, 56, 100, 180, and 300min after; and 24, 48, and 72h after 3.2mg/kg (i.m.) lisdexamfetamine administration in the four discrimination monkeys. Samples were immediately centrifuged at 1 000g for 10min. The plasma supernatant was transferred into a labeled storage tube and frozen at -80°C until analyzed. The identification and quantification of lisdexamfetamine and d-amphetamine were accomplished using a 3 200 Q trap with a turbo V source for Turbolon Spray (Applied Biosystems) run in multiple reaction monitoring mode and attached to a Shimadzu SCL high-performance liquid chromatography system controlled by Analyst 1.4.2 software. Additional methodological details are provided in the Supplementary Materials.

Data Analysis

A hysteresis graph was generated by plotting %CAR as a function of plasma d-amphetamine level (ng/mL) at all time points after 3.2mg/kg lisdexamfetamine administration. For comparison, a similar graph was generated from previously published data relating %CAR to plasma phenmetrazine levels after administration of 3.2mg/kg phendimetrazine, which is a prodrug for phenmetrazine (Banks et al., 2013c). Hysteresis loops were statistically analyzed by estimating the maximum difference between %CAR as levels decreased to their maximum value, compared to when levels increased to their maximum value (see Rowley et al., 2012). Separate quadratic equations were fit to the increasing and decreasing portions of the concentration-effect curves to derive an estimated maximum difference score (Δy). For increasing drug concentrations, a quadratic equation (y = ax2 + bx + c) was fit to the data of each monkey, and for decreasing drug concentrations, a separate quadratic equation (y = dx2 + ex + f) was fit: in both equations, a–f are coefficients and x is drug concentration. The concentration level at which the maximum difference between %CAR and drug concentration would be predicted to occur is x = (e-b)/(2*(a-d)). If the concentration level at which the difference score is predicted to be maximal was not in the obtained range of concentrations, the predicted maximum difference was set to 0. Otherwise, the maximum difference score was calculated from the best-fitting quadratic parameters as Δy = f-c + (a-d)x2. The estimated maximum difference scores for d-amphetamine and phenmetrazine were each analyzed by Wilcoxon Signed Rank Tests to determine whether the scores were significantly different from 0. The criterion for significance was set a priori at the 95% level of confidence (p < 0.05). Quadratic parameters were estimated for individual monkeys using the Solver optimization tool in Microsoft Excel for Mac 2011, and inferential statistics were conducted using JMP Pro 10 for Mac (SAS Institute).

Cocaine Versus Food Choice Procedure

Daily experimental sessions were conducted from 0900 to 1100h in each monkey’s home chamber as described previously (Banks et al., 2011, 2013b, 2014). The terminal choice schedule consisted of five 20min components separated by 5min inter-component intervals during which responding had no scheduled consequences. During each component, the left, food-associated key was transilluminated red, and completion of the FR requirement (FR100) resulted in food pellet delivery. In addition, the right, cocaine-associated key was transilluminated green, and completion of the FR requirement (FR10) resulted in delivery of the i.v. unit cocaine dose available during that component. The unit cocaine doses available during each of the five successive components were 0, 0.0032, 0.01, 0.032, and 0.1mg/kg/injection, respectively. Stimulus lights on the cocaine-associated key flashed on and off in 3 s cycles, and longer flashes were associated with higher cocaine doses. Ratio requirement completion initiated a 3 s timeout, during which all stimulus lights were turned off, and responding had no scheduled consequences. Choice behavior was considered to be stable when at least 80% cocaine versus food choice varied by ≤0.5 log units for 3 consecutive days at the lowest unit cocaine dose.

Once cocaine versus food choice was stable, test periods were conducted to determine lisdexamfetamine or d-amphetamine (positive control) treatment effects on cocaine versus food choice. For lisdexamfetamine studies, a lisdexamfetamine dose (0.32–3.2mg/kg) or saline was administered i.m. between 0755 and 0805h before the start of the 0900h behavioral choice session for 7 consecutive days. For d-amphetamine studies, d-amphetamine (0.032–0.1mg/kg/h) instead of saline was administered i.v. for 7 consecutive days via the treatment pump, and a 7-day period of saline infusion was used as the control. At the conclusion of each 7-day treatment period, treatments were terminated for at least 4 days and until cocaine versus food choice had returned to pretest levels. Saline, lisdexamfetamine, and d-amphetamine doses were counterbalanced across subjects. Although four monkeys completed the 7-day 1.0mg/kg/day lisdexamfetamine treatment condition, only three monkeys completed the saline, 0.32, and 3.2mg/kg/day lisdexamfetamine treatment. One monkey died during the study due to health complications unrelated to experimental manipulations. Three of the four monkeys tested with lisdexamfetamine were also tested with d-amphetamine, and in these monkeys, d-amphetamine was tested approximately 1 year before lisdexamfetamine. For the fourth monkey tested with d-amphetamine, all veins suitable for catheterization were exhausted before lisdexamfetamine treatments could be initiated.

Data Analysis

For cocaine versus food choice sessions, the primary dependent measure for each component was percent cocaine choice, defined as (number of ratio requirement choices completed on the cocaine-associated key/total number of ratio requirement choices completed on both the cocaine- and food-associated keys)*100. Mean data from the last 3 days of each 7-day lisdexamfetamine, d-amphetamine, or saline treatment were averaged for each individual monkey and then averaged across monkeys to yield group mean data. Percent cocaine choice was then plotted as a function of the unit cocaine dose and analyzed using a mixed-model analysis (JMP Pro 11, SAS), with lisdexamfetamine or d-amphetamine dose and unit cocaine dose as the fixed main effects and subject as the random effect. A post hoc Dunnett’s test was performed to compare lisdexamfetamine or d-amphetamine effects to saline treatment effects within a unit cocaine dose. Additional dependent measures collected during each behavioral session included the numbers of food and cocaine choices per component and the numbers of food, cocaine, and total choices across all components, and these data were analyzed using one- or two-way repeated-measures analyses of variance and a Dunnett’s post hoc test as appropriate. The criterion for significance was set a priori at the 95% confidence level (p < 0.05).

Drugs

The National Institute on Drug Abuse Drug Supply Program provided (−)-Cocaine HCl.. The d-amphetamine hemisulfate was purchased from Sigma Aldrich. Bruce Blough (RTI) synthesized lisdexamfetamine mesylate. Cocaine, d-amphetamine, and lisdexamfetamine were dissolved in sterile water, and all solutions were passed through a 0.22 micron Millipore sterile filter before use. Drug doses were calculated and expressed using the salt forms listed above.

Results

Time Course of Lisdexamfetamine and d-Amphetamine Discriminative Stimulus Effects

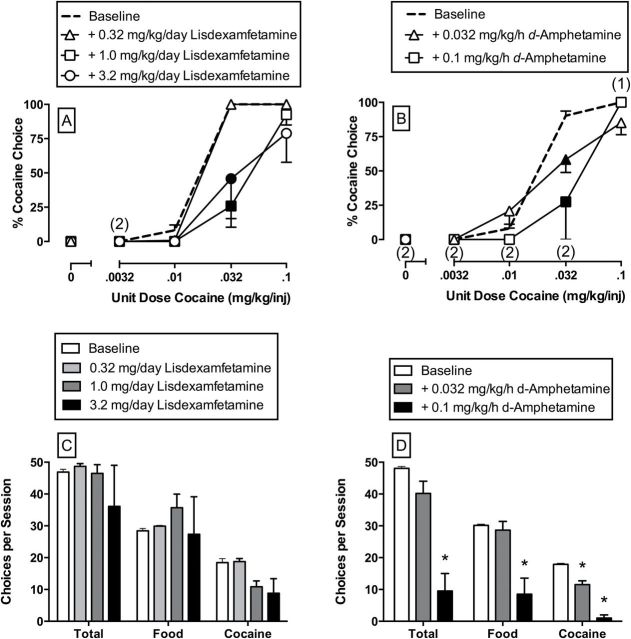

On cocaine and saline training days preceding test days, mean ± standard error of the mean percentages of injection-appropriate response were 100±0 and 99.8±0.2%, and rates of response were 2.6±0.3 and 2.5±0.3, respectively. Figure 1 shows the potency and timecourse of lisdexamfetamine (1A) and d-amphetamine (1B) to produce cocaine-like discriminative stimulus effects. Supplementary Figure 1 shows a potency comparison between lisdexamfetamine and d-amphetamine to produce full cocaine-like effects. Lisdexamfetamine produced a significant dose-dependent (F3,9 = 24.9, p = 0.0001) and time-dependent (F6,18 = 18.1, p < 0.0001) increase in cocaine-appropriate responses (interaction: F18,54 = 1.8, p = 0.0545). Doses of 1.0 and 3.2mg/kg lisdexamfetamine produced significant cocaine-appropriate responses from 56–300min and 10min to 48h, respectively. d-Amphetamine also produced a significant dose-dependent (F3,9 = 39.2, p < 0.0001) and time-dependent (F6,18 = 6.25, p = 0.0011) increase in cocaine-appropriate responses (interaction: F18,54 = 4.2, p < 0.0001). Doses of 0.1 and 0.32mg/kg d-amphetamine produced significant cocaine-appropriate responses from 10–180 and 10–300min, respectively.

Figure 1.

Potency and time course of the discriminative stimulus effects of lisdexamfetamine (0.32–3.2mg/kg, i.m.) and d-amphetamine (0.032–0.32mg/kg, i.m.) in male rhesus monkeys (n = 4) trained to discriminate cocaine (0.32mg/kg, i.m.) versus saline. Abscissae: time in min or h after injection. Top ordinates: percent cocaine-appropriate responses. Bottom ordinates: rates of response in responses per second. Symbols above “S” and “C” represent the group averages for all saline- and cocaine-training sessions preceding test sessions, respectively. Filled symbols indicate statistical significance compared to saline at a given time point (p < 0.05).

Figure 1 shows corresponding rates of operant responding as a function of time after lisdexamfetamine (1C) and d-amphetamine (1D) administration. Lisdexamfetamine (1.0mg/kg) significantly increased rates of operant responses 56, 100, and 300min post-administration compared to saline (interaction: F18,54 = 2.6, p = 0.0032). In contrast, there were no significant effects of d-amphetamine on rates of operant responding.

Plasma Lisdexamfetamine and d-Amphetamine Levels After Lisdexamfetamine administration

Supplementary Table 1 shows mean plasma lisdexamfetamine and d-amphetamine levels as a function of time after 3.2mg/kg i.m. lisdexamfetamine administration. Lisdexamfetamine was detectable in three out of four monkeys, and levels peaked at 10min in two monkeys and at 30min in the third monkey. There was no detectable lisdexamfetamine in the plasma 24h post-administration in any monkey. In contrast, d-amphetamine levels were detectable in all four monkeys, and d-amphetamine levels peaked at 30min in three monkeys and 56min in the fourth monkey. There was no detectable d-amphetamine in the plasma of any monkey 72h after lisdexamfetamine administration.

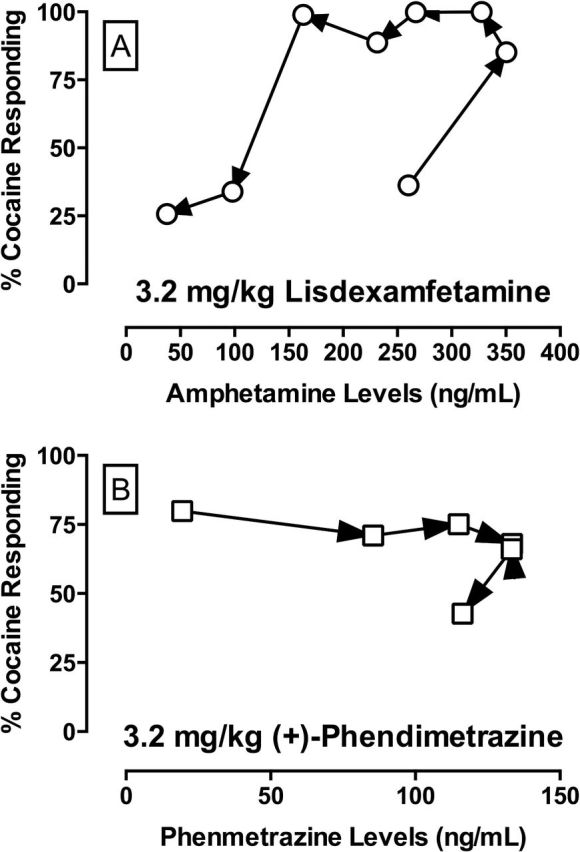

Figure 2A shows the counter-clockwise hysteresis loop of cocaine-like discriminative stimulus effects after 3.2mg/kg lisdexamfetamine administration as a function of plasma d-amphetamine levels (Δy = 72.2±18.7; W = 10, p < 0.001). For comparison, we also generated a hysteresis loop (Figure 2B) for phendimetrazine, a phenmetrazine prodrug, from previously published data (Banks et al., 2013c). In contrast to the results with lisdexamfetamine, cocaine-appropriate responses and plasma phenmetrazine levels displayed a clockwise rotation (Δy = -14.8±14.5; W = -4, p < 0.001).

Figure 2.

(A) Hysteresis plot of cocaine-appropriate responding in the discrimination procedure as a function of plasma d-amphetamine levels after 3.2mg/kg lisdexamfetamine administration. (B) For comparison, we also show a hysteresis plot of cocaine-appropriate responding and plasma (+)-phenmetrazine levels after 3.2mg/kg (+)-phendimetrazine administration from previously published results (Banks et al., 2013c).

Lisdexamfetamine and d-Amphetamine Treatment Effects on Cocaine Versus Food Choice

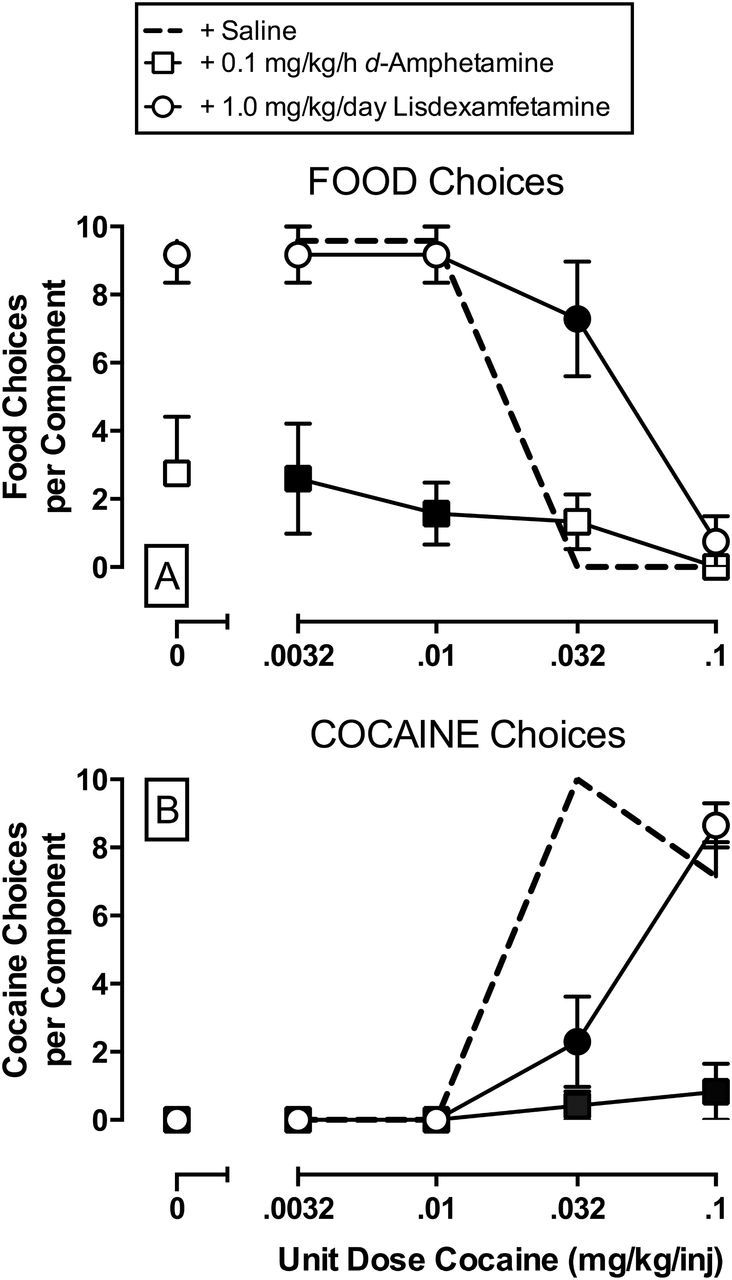

Under baseline control conditions when saline was infused through the treatment lumen of the double-lumen catheter, cocaine maintained a dose-dependent increase in preference over 1g food pellets in all monkeys (Figure 3A and B). When low (0.0032 and 0.01mg/kg/injection cocaine) unit cocaine doses were available as the alternative to food pellets, the monkeys responded almost exclusively on the food-associated key. As the unit cocaine dose increased, behavior was reallocated away from the food-associated key to an almost exclusive preference for 0.032 and 0.1mg/kg/injection unit cocaine doses. There was no statistically significant effect of i.m. saline injections on cocaine versus food choice. Thus, baseline (before i.m. injections of saline or lisdexamfetamine) and i.m. saline results were averaged, and these average data served as the statistical comparison to lisdexamfetamine treatment effects (Figure 3A).

Figure 3.

Effects of 7-day treatment with lisdexamfetamine (0.32–3.2mg/kg/day, i.m.; A and C) and d-amphetamine (0.032–0.1mg/kg/h, i.v.; B and D) on cocaine versus food choice in rhesus monkeys (n = 3–4). The top panels show lisdexamfetamine and d-amphetamine effects on cocaine choice dose-effect curves. Abscissae: unit dose cocaine in mg/kg/injection. Ordinates: % cocaine choice. The bottom panels are summary results for lisdexamfetamine and d-amphetamine effects on the number of total choices, food choices, and cocaine choices summed across all cocaine doses. All points and bars represent mean data ± standard error of the mean obtained during days 5–7 of each 7-day treatment period from three monkeys (0.32 and 3.2mg/kg/day lisdexamfetamine) or four monkeys (1.0mg/kg/day lisdexamfetamine; all d-amphetamine doses). Filled symbols in the top panels and asterisks in the bottom panels indicate statistical significance compared to baseline conditions (saline; p < 0.05). Numbers in parentheses indicate the number of subjects contributing to that data point if less than the total number of subjects tested and indicative of a time point where a monkey failed to complete at least one ratio requirement during the choice component.

Figure 3 shows lisdexamfetamine (3A) and d-amphetamine (3B) treatment effects on cocaine versus food choice. Both 1.0 and 3.2mg/kg/day lisdexamfetamine significantly decreased the preference of 0.032mg/kg/injection cocaine (interaction: F12,46.3 = 4.5, p < 0.0001). Similarly, both 0.032mg/kg/h and 0.1mg/kg/h d-amphetamine treatment significantly decreased preference of 0.032mg/kg/injection cocaine (interaction: F8,34 = 3.8, p = 0.0026). Figure 3 shows lisdexamfetamine (3C) and d-amphetamine (3D) treatment effects on total choices, food choices, and cocaine choices during the entire behavioral session. Mixed-model analyses demonstrated a significant main effect of the lisdexamfetamine dose on cocaine choices (F3,8 = 4.4, p = 0.0405); however, post hoc analyses using Dunnett’s test failed to detect any lisdexamfetamine dose that significantly decreased the number of cocaine choices earned relative to baseline. The 3.2mg/kg/day lisdexamfetamine treatment effects approached the alpha significance threshold (t-ratio: -2.81; p = 0.0566). In contrast, lisdexamfetamine had no significant effect on either total choices or food choices completed during the behavioral session. Continuous 0.1mg/kg/h d-amphetamine treatment significantly decreased both total choices (F2,6 = 25.0, p = 0.0012) and food choices (F2,6 = 11.6, p = 0.0087). In addition, both 0.032 and 0.1mg/kg/h d-amphetamine treatment significantly decreased cocaine choices (F2,6 = 100.1, p < 0.0001). In summary, 7-day treatments with either lisdexamfetamine or d-amphetamine significantly decreased cocaine versus food preference. However, in contrast to d-amphetamine, lisdexamfetamine did not decrease overall rates of response.

Figure 4 compares d-amphetamine (0.1mg/kg/h) and lisdexamfetamine (1.0mg/kg/day) effects on food (A) and cocaine (B) choices completed per component. The d-amphetamine treatment significantly decreased the number of food choices completed (interaction: F6,18 = 20.6, p < 0.0001) during concurrent availability of 0.0032 and 0.01mg/kg/injection cocaine and food pellets, and decreased the number of cocaine choices completed (interaction: F6,18 = 31.5, p < 0.0001) during concurrent availability of 0.032 and 0.1mg/kg/injection cocaine and food pellets. Lisdexamfetamine treatment significantly increased the number of food choices completed (interaction: F6,18 = 20.6, p < 0.0001) and significantly decreased the number of cocaine choices completed (interaction: F6,18 = 31.5, p < 0.0001) during concurrent availability of 0.032mg/kg/injection cocaine and food pellets.

Figure 4.

Effects of 7-day treatment with 0.1mg/kg/h d-amphetamine or 1.0mg/kg/day lisdexamfetamine treatment on the number of food (A) and cocaine (B) choices completed per choice session component in rhesus monkeys (n = 4). Abscissae: unit dose cocaine in mg/kg/injection that was available during each component of concurrent cocaine and food availability. Ordinates: choices completed per choice component. Filled symbols indicate statistical significant compared to baseline conditions (saline; p < 0.05).

Discussion

The present study determined lisdexamfetamine effects in rhesus monkeys using two procedures: (1) a two-key food-reinforced cocaine discrimination procedure to assess the potency and time course of lisdexamfetamine’s cocaine-like discriminative stimulus effects; and (2) a cocaine versus food choice procedure to assess treatment efficacy in a preclinical model of cocaine addiction. There were two main findings. First, both lisdexamfetamine and d-amphetamine produced dose-dependent and complete substitution for the discriminative stimulus effects of cocaine; however, lisdexamfetamine had lower potency (Supplementary Figure 1), a slower onset, and a longer duration of action than d-amphetamine. These results support the characterization of lisdexamfetamine as an agonist medication potentially capable of producing cocaine-like behavioral effects, and suggest that lisdexamfetamine may also have lower abuse potential than d-amphetamine, despite the same classification as a Drug Enforcement Agency Schedule II controlled substance. Second, 7-day lisdexamfetamine (1 and 3.2mg/kg/day, i.m.) treatment significantly decreased 0.032mg/kg/injection cocaine preference. Moreover, lisdexamfetamine treatment efficacy was qualitatively similar to d-amphetamine treatment. Overall, these results support further consideration of lisdexamfetamine’s potential as an agonist pharmacotherapy for cocaine addiction.

Cocaine-Like Effects of Lisdexamfetamine

Agonist medications are defined in part by shared pharmacodynamic mechanisms with the target drug of abuse. Results of the present study support the characterization of lisdexamfetamine as a potential agonist medication for cocaine abuse, and further suggest that cocaine-like effects of lisdexamfetamine are mediated exclusively by its active metabolite d-amphetamine in rhesus monkeys. First, like d-amphetamine (Kleven et al., 1990; Banks et al., 2014), lisdexamfetamine produced full substitution for the discriminative stimulus effects of cocaine. These results confirm and extend previous studies determining the discriminative stimulus effects of lisdexamfetamine in rats trained to discriminate d-amphetamine (Heal et al., 2013). In that study, lisdexamfetamine produced full substitution for d-amphetamine, and as in the present study with cocaine-trained monkeys, lisdexamfetamine was 10-fold less potent than d-amphetamine. Secondly, lisdexamfetamine produced cocaine-like discriminative stimulus effects with a slower onset and longer duration of action compared to d-amphetamine. These results confirm and extend a previous study determining onset and duration of lisdexamfetamine behavioral effects in rats (Heal et al., 2013). Lastly, lisdexamfetamine was rapidly converted to d-amphetamine after intramuscular administration consistent with previous pharmacokinetic results reported after i.v. (Jasinski and Krishnan, 2009a) and oral (Jasinski and Krishnan, 2009b; Ermer et al., 2010) administration in humans and intraperitoneal administration in rats (Rowley et al., 2012). For example, lisdexamfetamine plasma levels peaked at 10min, and at a time when lisdexamfetamine only produced a 36% cocaine-appropriate response. In contrast, d-amphetamine levels peaked at 56min after lisdexamfetamine administration, and at a time when the cocaine-appropriate response was 100%. Moreover, plasma lisdexamfetamine levels were at least 9-fold lower than d-amphetamine levels at time points (100–300min) associated with full cocaine-like discriminative stimulus effects. Overall, these results suggest that behaviorally active lisdexamfetamine doses generated sufficiently high plasma d-amphetamine levels to support lisdexamfetamine’s cocaine-like discriminative stimulus effects.

Hysteresis loops have been utilized to understand pharmacodynamic-pharmacokinetic relationships by plotting the time lag of either increases or decreases in the magnitude of pharmacological effects (e.g. cocaine-appropriate responding) at a given plasma drug level (Louizos et al., 2014). For example, a clockwise hysteresis loop was reported for the relationship between plasma cocaine levels and cocaine-appropriate responses after cocaine administration in rhesus monkeys (Lamas et al., 1995) and for the relationship between plasma cocaine levels and cocaine-induced subjective effects in humans (Jenkins et al., 2002). A clockwise hysteresis loop indicates the pharmacological effect decreased as a function of time for a given drug level and may be indicative of acute tolerance (Louizos et al., 2014). Consistent with previous lisdexamfetamine studies in rodents (Rowley et al., 2012), a counter-clockwise hysteresis loop was observed in the present study for plasma amphetamine levels and cocaine-appropriate responses after lisdexamfetamine administration. A counter-clockwise hysteresis loop indicates the pharmacological effect increased as a function of time for a given drug level (Louizos et al., 2014) and, in the specific case of lisdexamfetamine, would be consistent with an inactive prodrug (lisdexamfetamine) metabolizing to an active metabolite (d-amphetamine). In contrast to lisdexamfetamine, the prodrug phendimetrazine displayed a clockwise hysteresis loop (data reanalyzed from Banks et al., 2013c), which suggests that phendimetrazine is an active parent drug for an active metabolite. Overall, these differential hysteresis effects between the prodrugs lisdexamfetamine and phendimetrazine are consistent with the differential onsets of cocaine-appropriate responses produced by these two compounds in the cocaine discrimination procedure. Said another way, the cocaine-like discriminative stimulus effects of lisdexamfetamine are mediated exclusively by the conversion of lisdexamfetamine to d-amphetamine; in contrast, both the parent drug phendimetrazine and the active metabolite phenmetrazine contribute to the cocaine-like effects of phendimetrazine.

Lisdexamfetamine Effects on Cocaine Choice

Consistent with previous studies from our nonhuman primate laboratory (Negus, 2003; Banks et al., 2013b) and other rodent (Kerstetter et al., 2012; Thomsen et al., 2013), nonhuman primate (Nader and Woolverton, 1991; Czoty and Nader, 2013), and human (Hart et al., 2000; Rush et al., 2010) laboratory studies, cocaine maintained a dose-dependent increase in preference over an alternative, non-drug reinforcer. Also consistent with previous studies in nonhuman primates (Negus, 2003; Banks et al., 2013b) and rats (Thomsen et al., 2013), chronic d-amphetamine treatment attenuated cocaine versus food choice. The present study extends these previous findings by showing that chronic 7-day treatment with lisdexamfetamine also produced a dose-dependent rightward shift in the cocaine choice dose-effect curve. Insofar as reductions in cocaine choice by chronic d-amphetamine treatment in monkeys are consistent with clinical effectiveness of amphetamine maintenance to reduce cocaine use (Grabowski et al., 2001; Mariani et al., 2012), these results suggest that lisdexamfetamine may also be clinically effective to reduce cocaine use. Moreover, the present results also provide evidence for effectiveness of lisdexamfetamine not only to reduce cocaine consumption, but also to promote reallocation of behavior away from cocaine choice and toward food choice. This was especially evident in the present study when monkeys were treated with 1.0mg/kg/day lisdexamfetamine and chose between 0.032mg/kg/injection cocaine and food. Under these conditions, lisdexamfetamine significantly reduced cocaine choice and increased food choice without altering the total number of reinforcers earned. These results provide particularly strong evidence that lisdexamfetamine treatment can reduce the relative reinforcing effects of cocaine versus food without producing potentially problematic non-specific effects on overall rates of operant responses.

Prodrug Monoamine Releaser Compounds as Anti-Cocaine Addiction Medications

Monoamine releasers such as d-amphetamine, methamphetamine, and phenmetrazine have demonstrated efficacy to reduce cocaine-taking behaviors across a broad range of experimental endpoints in humans (Grabowski et al., 2001; Mooney et al., 2009; Greenwald et al., 2010; Rush et al., 2010), nonhuman primates (Negus, 2003; Czoty et al., 2011), and rodents (Chiodo et al., 2008; Thomsen et al., 2013). However, legitimate concerns regarding the abuse liability of these compounds hinder broad clinical deployment and regulatory agency support (for a circumspective on the potential problems and hurdles to deploy agonist-based medications for cocaine addiction, see Negus and Henningfield, 2014). Prodrugs represent one potential method for addressing abuse liability concerns because of the slower onset of effects and prolonged duration of action compared to the active metabolite. To date, two prodrugs have been examined as candidate pharmacotherapies in preclinical models of cocaine addiction: phendimetrazine (Banks et al., 2013b, 2013d) and lisdexamfetamine (present study). Both compounds decreased cocaine choice and produced a reciprocal increase in food choice, which is the desired pharmacotherapy profile of a medication being considered to treat drug addiction (Volkow et al., 2004; Vocci, 2007). Moreover, data discussed here suggest that lisdexamfetamine may be preferable to phendimetrazine because of its counter-clockwise hysteresis plot, suggestive of activity for only the metabolite and not the parent drug. Phendimetrazine is currently being evaluated in a human laboratory safety study as a potential pharmacotherapy for cocaine addiction (NCT02233647). Furthermore, a pilot study (NCT01490216) and a double-blind placebo-controlled clinical trial (NCT00958282) determining lisdexamfetamine treatment efficacy for cocaine addiction have been completed, and another pilot study (NCT01486810) is currently ongoing. These clinical studies will provide important new data to assess both: (A) the clinical utility of phendimetrazine and lisdexamfetamine as candidate pharmacotherapies; and (B) the predictive validity of preclinical drug versus food choice procedures as tools to study candidate pharmacotherapies.

Supplementary Material

For supplementary material accompanying this paper, visit http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S00000000000000.

Statement of Interest

Dr Banks’ research has been funded by the NIH. During the past 3 years, he has received compensation as a collaborator with the pharmaceutical companies Abbott and Purdue for projects related to opioid pharmacology and analgesic drug development. Dr Hutsell and Mr. Poklis declare no conflicts of interest. Dr Blough’s research has been funded by the NIH. Dr Negus’ research has been funded by the NIH, and during the past 3 years he has received compensation as a consultant for or collaborator with Abbott Pharmaceutical Company for projects related to analgesic drug development.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Research reported in this publication was supported by National Institutes of Heath (NIH) grants R01-DA026946, R01-DA012970, P30-DA033934, and T32-DA007027. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

We acknowledge the technical assistance of Jennifer Gough, Crystal Reyns, and Doug Smith. We also acknowledge Kevin Costa for writing the original version of the behavioral computer programs.

References

- Ahmed SH, Lenoir M, Guillem K. (2013) Neurobiology of addiction versus drug use driven by lack of choice. Curr Opin Neurobiol 23:581–587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balster RL, Schuster CR. (1973) Fixed-interval schedule of cocaine reinforcement: effect of dose and infusion duration. J Exp Anal Behav 20:119–129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banks ML. (2014) Effects of the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor antagonist mecamylamine on the discriminative stimulus effects of cocaine in male rhesus monkeys. Exp Clin Psychopharm 22:266–273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banks ML, Negus SS. (2012) Preclinical determinants of drug choice under concurrent schedules of drug self-administration. Adv Pharmacol Sci 2012:281768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banks ML, Blough BE, Negus SS. (2011) Effects of monoamine releasers with varying selectivity for releasing dopamine/norepinephrine versus serotonin on choice between cocaine and food in rhesus monkeys. Behav Pharmacol 22:824–836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banks ML, Blough BE, Stevens Negus S. (2013a) Interaction between behavioral and pharmacological treatment strategies to decrease cocaine choice in rhesus monkeys. Neuropsychopharmacology 38:395–404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banks ML, Blough BE, Negus SS. (2013b) Effects of 14-day treatment with the schedule III anorectic phendimetrazine on choice between cocaine and food in rhesus monkeys. Drug Alcohol Depend 131:204–213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banks ML, Blough BE, Fennell TR, Snyder RW, Negus SS. (2013c) Role of phenmetrazine as an active metabolite of phendimetrazine: Evidence from studies of drug discrimination and pharmacokinetics in rhesus monkeys. Drug Alcohol Depend 130:158–166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banks ML, Blough BE, Fennell TR, Snyder RW, Negus SS. (2013d) Effects of phendimetrazine treatment on cocaine vs food choice and extended-access cocaine consumption in rhesus monkeys. Neuropsychopharmacology 38:2698–2707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banks ML, Bauer CT, Blough BE, Rothman RB, Partilla JS, Baumann MH, Negus SS. (2014) Abuse-related effects of dual dopamine/serotonin releasers with varying potency to release norepinephrine in male rats and rhesus monkeys. Exp Clin Psychopharm 22:274–284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell J. (2014) Pharmacological maintenance treatments of opiate addiction. Br J Clin Pharmacol 77:253–263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiodo KA, Läck CM, Roberts DCS. (2008) Cocaine self-administration reinforced on a progressive ratio schedule decreases with continuous d-amphetamine treatment in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 200:465–473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comer SD, Ashworth JB, Foltin RW, Johanson CE, Zacny JP, Walsh SL. (2008) The role of human drug self-administration procedures in the development of medications. Drug Alcohol Depend 96:1–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czoty PW, Nader MA. (2013) Effects of dopamine D2/D3 receptor ligands on food-cocaine choice in socially housed male cynomolgus monkeys. J Pharm Exp Ther 344:329–338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czoty PW, Gould RW, Martelle JL, Nader MA. (2011) Prolonged attenuation of the reinforcing strength of cocaine by chronic d-amphetamine in rhesus monkeys. Neuropsychopharmacology 36:539–547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dole VP, Nyswander ME, Kreek MJ. (1966) Narcotic blockade. Arch Intern Med 118:304–309. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ermer J, Homolka R, Martin P, Buckwalter M, Purkayastha J, Roesch B. (2010) Lisdexamfetamine dimesylate: Linear dose-proportionality, low intersubject and intrasubject variability, and safety in an open-label single-dose pharmacokinetic study in healthy adult volunteers. J Clin Psychopharmacol 50:1001–1010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grabowski J, Rhoades H, Schmitz J, Stotts A, Daruzska LA, Creson D, Moeller FG. (2001) Dextroamphetamine for cocaine-dependence treatment: a double-blind randomized clinical trial. J Clin Psychopharmacol 21:522–526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grabowski J, Rhoades H, Stotts A, Cowan K, Kopecky C, Dougherty A, Moeller FG, Hassan S, Schmitz J. (2004a) Agonist-like or antagonist-like treatment for cocaine dependence with methadone for heroin dependence: Two double-blind randomized clinical trials. Neuropsychopharmacology 29:969–981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grabowski J, Shearer J, Merrill J, Negus SS. (2004b) Agonist-like, replacement pharmacotherapy for stimulant abuse and dependence. Addict Behav 29:1439–1464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenwald MK, Lundahl LH, Steinmiller CL. (2010) Sustained release d-amphetamine reduces cocaine but not “speedball”-seeking in buprenorphine-maintained volunteers: A test of dual-agonist pharmacotherapy for cocaine/heroin polydrug abusers. Neuropsychopharmacology 35:2624–2637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haney M, Spealman R. (2008) Controversies in translational research: drug self-administration. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 199:403–419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hart CL, Haney M, Foltin RW, Fischman MW. (2000) Alternative reinforcers differentially modify cocaine self-administration by humans. Behav Pharmacol 11:87–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heal DJ, Buckley NW, Gosden J, Slater N, France CP, Hackett D. (2013) A preclinical evaluation of the discriminative and reinforcing properties of lisdexamfetamine in comparison to d-amfetamine, methylphenidate and modafinil. Neuropharmacology 73:348–358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herin DV, Rush CR, Grabowski J. (2010) Agonist-like pharmacotherapy for stimulant dependence: preclinical, human laboratory, and clinical studies. Ann NY Acad Sci 1187:76–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heyman GH. (2009) Addiction: a disorder of choice. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Huttunen KM, Raunio H, Rautio J. (2011) Prodrugs—from Serendipity to Rational Design. Pharmacol Rev 63:750–771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jasinski D, Krishnan S. (2009a) Human pharmacology of intravenous lisdexamfetamine dimesylate: abuse liability in adult stimulant abusers. J Psychopharmacol 23:410–418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jasinski D, Krishnan S. (2009b) Abuse liability and safety of oral lisdexamfetamine dimesylate in individuals with a history of stimulant abuse. J Psychopharmacol 23:419–427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins AJ, Keenan RM, Henningfield JE, Cone EJ. (2002) Correlation between pharmacological effects and plasma cocaine concentrations after smoked administration. J Anal Toxicol 26:382–392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerstetter KA, Ballis MA, Duffin-Lutgen S, Carr AE, Behrens AM, Kippin TE. (2012) Sex differences in selecting between food and cocaine reinforcement are mediated by estrogen. Neuropsychopharmacology 37:2605–2614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleven MS, Anthony EW, Woolverton WL. (1990) Pharmacological characterization of the discriminative stimulus effects of cocaine in rhesus monkeys. J Pharm Exp Ther 254:312–317. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreek MJ, LaForge KS, Butelman E. (2002) Pharmacotherapy of addictions. Nat Rev Drug Discov 1:710–726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamas X, Negus SS, Hall E, Mello NK. (1995) Relationship between the discriminative stimulus effects and plasma concentrations of intramuscular cocaine in rhesus monkeys. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 121:331–338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Louizos C, Yanez JA, Forrest ML, Davies NM. (2014) Understanding the hysteresis loop conundrum in pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic relationships. J Pharm Pharm Sci 17:34–91. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mariani JJ, Pavlicova M, Bisaga A, Nunes EV, Brooks DJ, Levin FR. (2012) Extended-release mixed amphetamine salts and topiramate for cocaine dependence: a randomized controlled trial. Biol Psychiatry 72:950–956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mooney ME, Herin DV, Schmitz JM, Moukaddam N, Green CE, Grabowski J. (2009) Effects of oral methamphetamine on cocaine use: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Drug Alcohol Depend 101:34–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nader M, Woolverton W. (1991) Effects of increasing the magnitude of an alternative reinforcer on drug choice in a discrete-trials choice procedure. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 105:169–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Negus SS. (2003) Rapid assessment of choice between cocaine and food in rhesus monkeys: Effects of environmental manipulations and treatment with d-amphetamine and flupenthixol. Neuropsychopharmacology 28:919–931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Negus SS, Henningfield J. (2014) Agonist medications for the treatment of cocaine use disorder. Neuropsychopharmacology. Advance online publication. Retrieved 11 Dec 2014. doi: 10.1038/npp.2014.322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pennick M. (2010) Absorption of lisdexamfetamine dimesylate and its enzymatic conversion to d-amphetamine. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat 6:317–327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pomara C, Cassano T, D’Errico S, Bello S, Romano AD, Riezzo I, Serviddio G. (2012) Data available on the extent of cocaine use and dependence: biochemistry, pharmacologic effects and global burden of disease of cocaine abusers. Curr Med Chem 19:5647–5657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothman RB, Blough BE, Woolverton WL, Anderson KG, Negus SS, Mello NK, Roth BL, Baumann MH. (2005) Development of a rationally designed, low abuse potential, biogenic amine releaser that suppresses cocaine self-administration. J Pharm Exp Ther 313:1361–1369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowley HL, Kulkarni R, Gosden J, Brammer R, Hackett D, Heal DJ. (2012) Lisdexamfetamine and immediate release d-amfetamine – Differences in pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic relationships revealed by striatal microdialysis in freely-moving rats with simultaneous determination of plasma drug concentrations and locomotor activity. Neuropharmacology 63:1064–1074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rush CR, Stoops WW, Sevak RJ, Hays LR. (2010) Cocaine choice in humans during D-amphetamine maintenance. J Clin Psychopharmacol 30:152–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schindler CW, Panlilio LV, Thorndike EB. (2009) Effect of rate of delivery of intravenous cocaine on self-administration in rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 93:375–381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoops WW, Rush CR. (2013) Agonist replacement for stimulant dependence: a review of clinical research. Curr Pharm Des 19:7026–7035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomsen M, Barrett AC, Negus SS, Caine SB. (2013) Cocaine versus food choice procedure in rats: environmental manipulations and effects of amphetamine. J Exp Anal Behav 99: 211–233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vocci FJ. (2007) Can replacement therapy work in the treatment of cocaine dependence? And what are we replacing anyway? Addiction 102:1888–1889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volkow ND, Fowler JS, Wang G-J. (2004) The addicted human brain viewed in the light of imaging studies: brain circuits and treatment strategies. Neuropharmacology 47, Supplement 1:3–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.