The attention recently paid to the story of Henrietta Lacks and her HeLa cell line following the publication of Rebecca Skloot’s highly acclaimed book, The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks, has highlighted the numerous scientific discoveries directly attributable to research utilizing this cell line.1 Shortly after its establishment, the limitless potential of the HeLa cell line became clearly apparent from its use in the propagation of the poliovirus. It was the need for massive amounts of HeLa cells for the evaluation of Dr. Jonas Salk’s polio vaccine that forever intertwined the history of Tuskegee University to the noteworthy history of the HeLa cell.

When the words research and Tuskegee University are mentioned in the same sentence, many individuals outside this University’s Lincoln Gates think of the important research conducted by Dr. George Washington Carver. And although Dr. Carver’s contributions are beyond reproach, when it comes to scientific research on Tuskegee’s campus, several of its lesser-known scientists have left their own indelible marks. Two such scientists, Drs. Russell W. Brown (Figure 1) and James H.M. Henderson (Figure 2) made their mark by leading a team of researchers and staff at Tuskegee University in the mass production of the infamous HeLa cells for use nationally in the development of the polio vaccine.

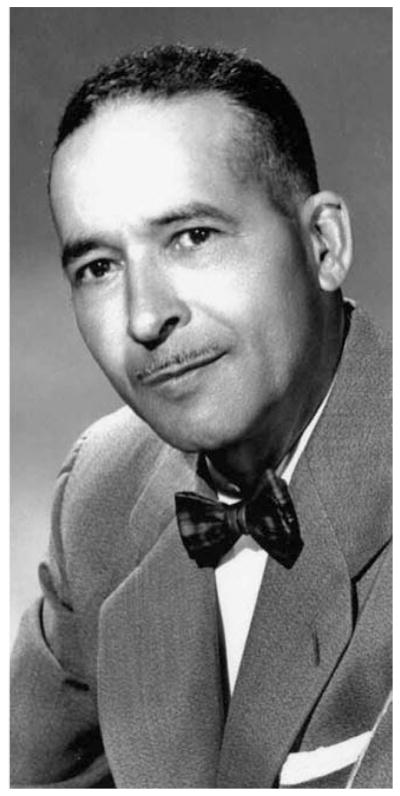

Figure 1.

Dr. Russell W. Brown, Principal Investigator of the Tuskegee University HeLa Cell Project.

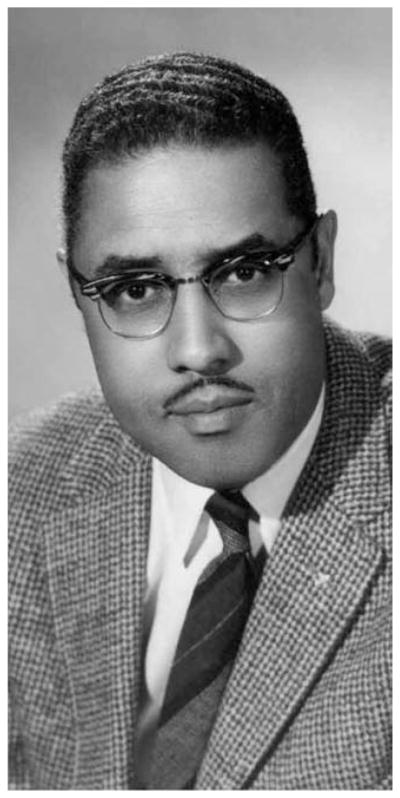

Figure 2.

Dr. H.M. Henderson, Co-Principal Investigator of the Tuskegee University HeLa Cell Project.

Historical perspective on polio among Blacks

Before going directly into the mass production of HeLa cells on Tuskegee’s campus, a brief historical perspective on the University’s prior involvement in polio treatment is warranted. Many factors and circumstances came into play to initiate Tuskegee’s involvement in the polio vaccine’s development. First and foremost, there was the prevalent racist climate found in this country. This attitude was expounded in the Southeast by Jim Crow discriminatory practices that belittled and held back Black people and made their lives more difficult. Compounding this was a ubiquitous belief in the orthopedic realm that Black polio victims were a rarity, with some people even believing that Blacks were immune to the disease. A combination of these factors led to a disregard for the suffering faced by Blacks infected with the polio virus.2

For over a decade, Black activists challenged such flawed thinking, and the idea that polio was a Whites-only disease.2 Dr. John Chenault, the head of Orthopedic Surgery at Tuskegee University’s John A. Andrew Memorial Hospital, and the eventual Director of the hospital’s Infantile Paralysis Unit was one such activist. Dr. Chenault conducted his own study in Alabama on the occurrence of polio in Blacks, and examined existing data on this subject from a Georgia Survey of Crippled Children. From his research, Dr. Chenault concluded that although the racial incidence of polio among Blacks was somewhat lower than among Whites, the fatalities observed were relatively higher. He found the disease (polio) caused approximately 20% of the crippling cases observed among Blacks. Dr. Chenault’s investigation led him to believe that the absence of quality treatment facilities for Blacks played a major role in the number cases witnessed.3,4

Establishment of the Tuskegee Infantile Paralysis Center

In 1936, a polio epidemic swept through the Southern region of the United States, severely crippling children, both Black and White. This outbreak further exposed the challenges that Black polio patients faced when seeking or receiving medical care. The discriminatory practices of the time, especially in the South, left most Black patients with the disease perpetually searching for suitable treatment facilities.2,4

In 1938, polio’s most famous victim, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt, founded the National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis (NFIP) to raise funding to specifically aid in the treatment and cure of polio. The NFIP’s mandate was to increase the research and education on polio throughout the world through the identification of the etiology and mode of transmission of the disease, and the development of treatment vaccines. One of its many fund-raising activities was the nationwide Annual Presidential Ball, an event supported by both Blacks and Whites throughout the country. As was customary during that time period, separate balls were held for Black and White patrons, although all contributions received were pooled into a central fund. It was from these collected funds that the extravagantly equipped and staffed Warm Springs Foundation in Georgia was established for the treatment of White polio patients only. However once the predicament of polio in the Black community was clearly articulated, an allout campaign was initiated to bring the racial disparity in funding of polio treatment squarely to the attention of the NFIP. This pressure was politically uncomfortable for President Roosevelt, since the President himself periodically visited the Warm Springs facilities for treatment.2

In this context, the burden of doing something for Black victims of polio fell squarely upon the shoulders of Mr. Basil O’Connor, president of the NFIP.2,4 O’Connor became a key liaison between the NFIP, Tuskegee University, and the John A. Andrew Memorial Hospital, which would eventually lead to the formation of the Tuskegee Infantile Paralysis Center in January 1940. The Tuskegee Infantile Paralysis Center, staffed by outstanding Black orthopedic surgeons, was created for the double purpose of treating Black children with polio and serving as a research and training base for Black health care professionals in the ongoing battle against this disease.4

The HeLa Cell Project

While polio patients from across the Southeast were being ushered through essential treatment and rehabilitation programs at the Tuskegee Infantile Paralysis Center, across campus Tuskegee scientists were conducting outstanding research in the Carver Research Foundation building. This building, partially constructed from the life savings of Dr. Carver, was also home to the labs of two of Tuskegee’s premier scientists, Drs. Russell Brown and James Henderson. Few, including these two scientists, had the premonition that this building would be transformed into a state-of-the-art cell culture factory to cultivate and distribute the cells that would be instrumental in the evaluation of the polio vaccine.4

The Rhesus monkey cell was the initial cell-of-choice to measure the quantity of antibody developed in response to the poliovirus infection. However, due to the inability to supply the large quantities of monkey cells needed for vaccine testing, an alternative source of host cells was needed. The highly proliferative nature of the HeLa cell and its innate ability to be easily infected by the poliovirus made it an ideal alternative source. Shortly after the HeLa cell strain was chosen as an alternative source to Rhesus monkey cells, the NFIP proposed the establishment of a central source to supply HeLa cultures to meet the anticipated needs of researchers testing the vaccine.1,2,4,5

Selection of Tuskegee University as a cell culture factory site

One may ask: what were the probable circumstances that led to the selection of Tuskegee University as the site for a HeLa Project? Since the NFIP desired that the HeLa cell project would conform to established cell culture protocols, its powers-to-be felt that such standards could be best achieved on university campuses, where the personnel would be knowledgeable and experienced in research. Because of the outstanding research conducted by Drs. Brown and Henderson in cell biology, Tuskegee University fit the criteria set by the NFIP. It probably did not hurt Tuskegee’s chances of landing a HeLa Project site that Dr. H.M. Weaver, Director of Research for the NFIP, was well acquainted with the ongoing work taking place in Tuskegee’s Carver Research Foundation. In addition, for many years, Mr. Basil O’Connor, Founder and Chief Administrator of the NFIP, was Chairman of the Board of Trustees of Tuskegee University. O’Connor’s regular presence on Tuskegee’s campus acquainted him personally with the school’s exceptional faculty and research facilities.4,5 Still others believe that Mr. Charles Bynum, the Director of “Negro Activities” at the NFIP was the main reason that Tuskegee was selected as a HeLa Project site. It is believed that Bynum, the first Black foundation executive in the United States, preferred Tuskegee because it would provide much-needed funding for jobs and training of Carver Research Foundation fellows and scientists, as well as funding of other research being conducted.4 Needless to say that all of these factors contributed in part to O’Connor’s selection of, and confidence in Tuskegee to do an exceptional job on the HeLa Project.

In October 1952, Dr. Weaver met with Dr. Russell Brown, Director of the Carver Research Foundation, to discuss the feasibility of a central HeLa production laboratory at Tuskegee University. During these discussions, it was mutually agreed that the project would be awarded to Tuskegee and supported by a grant from the NFIP. Dr. Brown was to serve as principal investigator (PI), with Dr. Henderson as co-PI. Weaver next arranged for both Brown and Henderson to spend three months and six weeks, respectively in an intensive cell and tissue culture training program at the University of Minnesota under the supervision of Drs. Jerome T. Syverton and William F. Scherer. During this training period, Brown and Henderson formulated the equipment, personnel, and facilities infrastructure needed for developing a preeminent cell culture laboratory. All of their requests and specifications were carried out to the letter.4,5

In April 1953, Dr. Scherer provided Tuskegee with the original seed culture of the HeLa cell line, which he obtained from the original propagator of the cell line, Dr. George Gey from Johns Hopkins University Hospital. Drs. Brown and Henderson trained all of their personnel in intricacies of cell and tissue culture. The Tuskegee team was given a goal of developing the capacity to ship a minimum of 10,000 cultures per week to various laboratories. In their original experimentation to identify the best protocol to ensure the successful transportation of viable HeLa cells, the Brown/Henderson team made important findings that revolutionized the process of commercialized cell culture. In the area of laboratory cell and tissue culture material, the HeLa Project was responsible for the routine use of rubber-lined screw-capped bottles and tubes. They also saw the need for specialization in the jobs of their personnel. This was seen in the hiring of what they referred to as an “expediter,” whose sole job was to be responsible for the procurement of necessary supplies. Drs. Brown and Henderson likewise instituted quality control measures through the employment of customary microscopic analyses to check cell morphology and the condition of culture monolayers before shipping.5

Several additional key innovations resulted from discovering that HeLa cells were extremely temperature sensitive. The following are some of the most pertinent innovations rendered. In order to ensure that they would have HeLa cells available in the event of equipment failure, Drs. Brown and Henderson decided to equip the laboratory with multiple incubators instead of a single large-capacity incubator. Their thinking behind this was that if one or more of the incubators’ thermostats failed and allowed temperatures to rise to lethal levels for some cells, they would not lose all cultures. The HeLa cells temperature sensitivity also forced the pair to formulate methods to circumvent the extreme temperatures encountered when shipping cells during the summer and winter months. They discovered that by packing one or two cans of Equitherm (i.e., sodium sulfate decahydrate) in each shipping package during the months of April to September, cell cultures were able to be maintained at a desired temperature of below 36° C. Further shipping innovations included the construction of the shipping container. Shipping containers were made of a heavy-duty cardboard box lined with fiberglass-aluminum sheet insulation. These specialized boxes were also equipped with cardboard separators to maintain the cultures in an upright position and to avoid accidental breakage.5

Through trial and error, and under intense pressure and scrutiny to perform, the Tuskegee HeLa team solved all of the intricate problems they encountered associated with the mass production of the HeLa cell line, including the maintenance of a noncontaminating environment and instituting exacting quality control measures. At its peak of production, approximately 20,000 tube cultures could be shipped per week. By June of 1955, the Tuskegee HeLa project had shipped approximately 600,000 cultures.4,5 In 1954, Microbiological Associates, Incorporated copied the successful template designed at Tuskegee University’s Carver Research Foundation. This template was used to set up a large-scale cell culture factory in a former Fritos factory in Bethesda, Maryland to begin mass-producing HeLa cells for global distribution, simultaneously ushering in a multibillion-dollar industry for the selling of biomedical specimens. The NFIP eventually closed down the Tuskegee HeLa cell factory as a consequence of dwindling demand for cells due to the competition from companies like the Microbiological Associates and other start-ups now supplying scientists with their cell demands.1 However, none of these occurrences can diminish Tuskegee University’s importance, its contributions, and impact on two biomedical fronts in the battle against poliomyelitis, for not only Blacks, but for all people.

Acknowledgments

Sources of funding. This work was made possible (in part) by grants R13MD006772 and G12RR003059/G12MD007585 from the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities and U54CA118623 from the National Cancer Institute.

The author would like to acknowledge the support received from the following grants that allowed this work to be formulated and developed: R13MD006772 and G12RR003059 from the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities, and U54CA118623 from the National Cancer Institute. The author would also like to thank friend and colleague, Dr. Stephen Olufemi Sodeke, for his critical review and edits of the paper that have truly enhanced the final product. In addition, the author would like to acknowledge the help and support given by the Tuskegee University Archives, especially the assistance given by Mr. Dana Chandler, Archivist, and Ms. Cheryl Ferguson, Archival Assistant. Finally, the author would like to thank, posthumously, Dr. James H.M. (Jimmy) Henderson for freely giving of his time and knowledge as he shared the history of the HeLa Project at Tuskegee University with me and the many students in my Foundations of Cancer Biology class, who were honored to hear him reminisce.

Footnotes

Disclaimers. The author has no conflicts of interest or previous publications in this particular area to declare.

Notes

- 1.Skloot R. The immortal life of Henrietta Lacks. 1. New York, NY: Crown Publishers; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rogers N. Race and the politics of polio: Warm Springs, Tuskegee, and the March of Dimes. Am J Public Health. 2007 May;97(5):784–95. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.095406. Epub 2007 Mar 29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chenault JW. Infantile paralysis (acute anterior poliomyelitis) J Natl Med Assoc. 1941 Sep;33(5):220–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Powell E, Jume J. A Black oasis: Tuskegee Institute’s fight against infantile paralysis. Tuskegee, AL: Tuskegee University Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brown RW, Henderson JHM. The mass production and distribution of HeLa cells at Tuskegee Institute, 1953–55. J Hist Med Allied Sci. 1983 Oct;38(4):415–31. doi: 10.1093/jhmas/38.4.415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]