Abstract

Objectives

Dietary cholesterol is the leading risk factor for cardiovascular disease and other chronic diseases. Changes in dietary patterns in China recently might have an impact on the trends of diet-related risk factors of chronic diseases. This study aims to monitor the changes in daily cholesterol intake and its food sources in Chinese adults.

Design

A longitudinal study using demographic and dietary data of adults younger than 60 years from eight waves (1991–2011) of the China Health and Nutrition Surveys was conducted. Mixed-effect models were used in this study.

Setting

The data were derived from urban and rural communities in nine provinces (autonomous regions) in China.

Participants

There were 21 273 participants (10 091 males and 11 182 females) in this study.

Outcomes

The major outcome is daily cholesterol intake amount, which was calculated by using the Chinese Food Composition Table, based on dietary data.

Results

The mean daily cholesterol intake in Chinese adults increased from 165.8 mg/day in 1991 to 266.3 mg/day in 2011. Cholesterol consumed by participants in different age (18–39 and 40–59 years), sex and urbanisation groups steadily elevated over time (p<0.0001), as did the proportions of participants with greater than 300 mg/day cholesterol consumption. In each subgroup, cholesterol originating from most of the food groups showed increasing trends over time (p<0.0001), except for animal fat and organ meats. Eggs, pork, fish and shellfish in that order remained the top three sources in 1991, 2000 and 2011, whereas milks were a negligible contributor. Cholesterol from animal fat declined and was insignificant in 2011 in most of the subgroups, while cholesterol being of poultry origin increased and became considerable in 2011.

Conclusions

Adults in China consumed increasingly high cholesterol and deviated from the recommended intake level over the past two decades. Adults need to pay more attention to intakes of eggs, pork, fish and shellfish.

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study observed that the amounts of daily cholesterol intake in Chinese adults steadily increase from 1991 to 2011, as does the proportion of participants with a greater cholesterol intake than 300 mg/day. Adults need to pay attention to the intake in the food groups of eggs, pork, fish and shellfish in China.

The primary limitation of this study is that the accuracy of daily cholesterol intake estimates was limited by the accuracy of recalls provided by survey participants, based on a dietary survey.

Food grouping can have a major influence on the ranked order of dietary sources, as the number of food grouping or the ingredients in food groups may be partially different compared to previous studies conducted in various countries.

Introduction

Adequate dietary intake is a cornerstone of health promotion and chronic disease prevention. Dietary habits of population are undergoing substantial changes along with the socioeconomic transition worldwide, including developing countries.1–3 Changes in dietary patterns might have an impact on the trends of diet-related risk factors of chronic diseases. Dietary cholesterol has been reported to link with the progression of liver disease,4 and higher risks of stroke5 and cardiovascular disease.6 Therefore, several countries have developed specific dietary cholesterol recommendations. Current US nutrition policy and Chinese Dietary Reference Intakes recommend limiting the intake of cholesterol to <300 mg/day for the general population.7 8

The National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2005–2006 reported mean intakes of 278 mg cholesterol/day in the USA, whereas adult females averaged 237 compared to 358 mg cholesterol/day for adult males.7 As the pervasive public health programmes are focusing on nutrition education, shifting from red meat to poultry, the general population is increasingly concerned about cholesterol intake. The trends in compliance with the dietary recommendations of the Swiss Society for Nutrition in the Geneva population were assessed for the period from 1999 to 2009 using 10 cross-sectional, population-based surveys, and found that the percentage of participants with a cholesterol intake of <300 mg/day increased from 40.8% in 1999 to 43.6% in 2009 for men and from 57.8% to 61.4% in women, although the quality of the Swiss diet did not improve over the study period.9 By contrast, few studies longitudinally reported that mean daily cholesterol intake and the proportion of people with a greater intake than the recommended amount increased in adults of both Taiwanese and Chinese origin.10 11 On the contrary, food sources of cholesterol may be undergoing great changes with the modifications in lifestyle and dietary habits worldwide. China has experienced extremely rapid economic growth over the past three decades, which induced the epidemic of a Western lifestyle. However, the dietary cholesterol intake status in Chinese in recent years is rarely reported. Taken together, the longitudinal studies targeted on the trends and food group patterns of dietary cholesterol intake in China are required.

By use of longitudinal data from the China Health and Nutrition Survey (CHNS), the aims of the present study were to examine the trends in dietary cholesterol intake and its food sources in Chinese adults younger than 60 years between 1991 and 2011, and to investigate the differences in dietary cholesterol intake across demographic factors.

Methods

Study population

We used data from the CHNS, which is an ongoing series of longitudinal household surveys with the goal of examining how the wide-ranging social and economic changes in China affect a wide array of nutrition and health-related outcomes. The CHNS conducted nine rounds between 1989 and 2011 in nine provinces (autonomous regions). A multistage, random cluster sample was used to select the survey sample in each province to make sure that the CHNS provided a representation of urban and rural areas. The survey design and methods have been described in detail elsewhere.12

Our analysis focused on the adult population aged 18–59 years; therefore, it used the eight waves of survey data between 1991 and 2011, given that the population composition in the 1989 survey consisted only of young adults. Of all the participants who had full socioeconomic status and demographic data, and 3-day, 24 h dietary recall data, we excluded pregnant or lactating women and those having implausible energy intakes (<800 kcal/day or >6000 kcal for men and <600 kcal or >4000 kcal for women).13 The current analysis therefore consisted of 21 273 participants (10 091 males and 11 182 females) clustered in 239 communities, resulting in 62 616 total responses in the eight survey years. The research was reviewed and approved by the Institute Review Board of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention.

Dietary data

Household food consumption data and individual dietary recall data were collected during three consecutive days including one weekend day and two weekdays.12 14 All foods and condiments in home inventory, purchased from markets, picked from gardens and food waste, were weighed and recorded at the beginning and end of the survey. Individual dietary intake data were collected by asking each household member to report all food consumed at home and away from home on a 3-day, 24 h recall basis, involving the types, amounts, type of meal and place of consumption.

Assessment of dietary cholesterol

The Chinese Food Composition Table was utilised to calculate the individual daily intake amount of cholesterol for each food item in the dietary data.

Evaluation of urbanisation

The standardised, validated urbanisation measure15 captures the changes in 12 dimensions at the community level, including population density, economic activity, traditional markets, modern markets, transportation infrastructure, sanitation, communications, housing, education, diversity, health infrastructure and social services. Each is based on numerous measures applicable to each dimension.

Statistical analysis

The values were expressed as mean±SE for continuous variables or as a percentage of the total for categorical variables. Data were analysed using both descriptive and analytic statistics. The study sample was subdivided according to different demographic factors. Adjusted means and SEs were used to describe the distribution of continuous variables after adjusting for complex sampling and covariates including age, sex and urbanisation. Age was adjusted as a continuous variable, and urbanisation as a categorical variable. Linear mixed-effect models using unstructured (UN) covariance patterns were used to calculate adjusted mean values of total dietary cholesterol, individual cholesterol intake from specific foods and the proportions of participants with more than 300 mg of cholesterol intake daily, and to examine the temporal trends after adjusting for intraclass correlation within clusters and covariates including age, sex and urbanisation. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS V.9.1 software (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina, USA).

Results

Subject demographic characteristics

This study focused on the adult population aged 18–59 years and the sample size was 7410 in 1991, 7399 in 1993, 7808 in 1997, 8551 in 2000, 7543 in 2004, 7290 in 2006, 7333 in 2009 and 9282 in 2011, respectively (table 1). The mean age ranged from 36.6 to 43.7 years, and a significant increased trend over the survey periods was observed (p<0.0001), although the differences between consecutive two survey years were mild. Slightly more than half (50.7–53.1%) of the participants were female in the eight survey years. In terms of urbanisation, the scores of low, medium and high urbanisation progressively increased across the survey years (p<0.0001), which indicated that dramatic urbanisation occurred in the past 20 years in China.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of participants in each survey year

| Number of participants | 1991 | 1993 | 1997 | 2000 | 2004 | 2006 | 2009 | 2011 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 7410 | 7399 | 7808 | 8551 | 7543 | 7290 | 7333 | 9282 | |

| Age (years)* | ||||||||

| Mean | 36.6 | 36.9 | 38.0 | 39.2 | 41.7 | 42.7 | 43.0 | 43.7 |

| SE | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 |

| Gender (%) | ||||||||

| Male | 47.2 | 48.1 | 49.3 | 49.2 | 47.9 | 47.9 | 48.3 | 46.9 |

| Female | 52.8 | 51.9 | 50.7 | 50.8 | 52.1 | 52.1 | 51.7 | 53.1 |

| Urbanisation (score) | ||||||||

| Low* | ||||||||

| Mean | 28.4 | 29.4 | 31.3 | 37.9 | 39.5 | 41.0 | 45.5 | 49.8 |

| SE | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 |

| Medium* | ||||||||

| Mean | 45.8 | 47.0 | 51.6 | 56.5 | 60.0 | 63.3 | 65.3 | 76.3 |

| SE | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.1 |

| High* | ||||||||

| Mean | 65.1 | 66.8 | 73.4 | 79.7 | 85.3 | 87.5 | 89.6 | 93.6 |

| SE | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 |

*Significant trend across the survey years (p<0.0001; test for trend).

Trends in daily cholesterol intake level by age, sex and urbanisation

During the 20-year period from 1991 to 2011, the average dietary cholesterol intake increased from 165.8 to 266.3 mg/day in Chinese adults (table 2). Furthermore, Chinese adults in different age (18–39 and 40–59 years), sex and urbanisation groups steadily consumed more cholesterol over time (p<0.0001). The mean cholesterol intake per day increased by 97.9 and 101.8 mg/day from 1991 to 2011 in two age groups, respectively. Similar increments were found in male and female groups. It is worth noting that the increase in daily cholesterol intake (112.1 mg/day) between 1991 and 2011 in adults from a low urbanisation area was considerable, which accounted for 109% of the intake level in 1991. Although the smallest absolute and relative changes (71.2 mg/day and 29.5%, respectively) over the survey period were observed in adults living in a high urbanisation area, the daily cholesterol intake was highest in each survey year.

Table 2.

Daily cholesterol intake (mg/day) by age, sex and urbanisation among Chinese adults younger than 60 years from 1991 to 2011*,†

| 1991 |

1993 |

1997 |

2000 |

2004 |

2006 |

2009 |

2011 |

AD‡ | RC, %§ | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SE | Mean | SE | Mean | SE | Mean | SE | Mean | SE | Mean | SE | Mean | SE | Mean | SE | |||

| All | 165.8 | 13.3 | 170.6 | 13.2 | 213.7 | 13.3 | 230.4 | 13.3 | 241.8 | 13.3 | 260.3 | 13.2 | 265.4 | 13.3 | 266.3 | 13.3 | 100.5 | 60.6 |

| Age group (years) | ||||||||||||||||||

| 18–39 | 165.6 | 12.9 | 170.4 | 12.9 | 211.9 | 12.9 | 229.7 | 13.4 | 236.9 | 12.9 | 258.3 | 13.2 | 258.9 | 13.0 | 263.5 | 13.4 | 97.9 | 59.1 |

| 40–59 | 167.4 | 13.6 | 171.5 | 13.6 | 217.9 | 13.5 | 231.1 | 12.8 | 243.8 | 13.4 | 260.8 | 12.8 | 266.8 | 13.4 | 269.2 | 13.0 | 101.8 | 60.8 |

| Sex | ||||||||||||||||||

| Male | 178.2 | 13.2 | 183.3 | 13.2 | 222.2 | 13.1 | 238.4 | 13.1 | 250.8 | 13.1 | 274.5 | 13.0 | 276.2 | 13.1 | 276.7 | 13.1 | 98.5 | 55.3 |

| Female | 157.9 | 12.9 | 161.5 | 12.9 | 209.6 | 12.9 | 224.8 | 12.9 | 233.4 | 12.9 | 245.4 | 12.7 | 253.0 | 12.9 | 254.9 | 12.9 | 97.0 | 61.4 |

| Urbanisation | ||||||||||||||||||

| Low | 102.8 | 16.3 | 105.5 | 16.3 | 122.0 | 16.3 | 159.5 | 16.3 | 170.7 | 16.3 | 199.1 | 16.2 | 209.7 | 16.3 | 214.9 | 16.3 | 112.1 | 109.0 |

| Medium | 168.2 | 16.5 | 171.5 | 16.5 | 222.6 | 16.5 | 235.0 | 16.4 | 248.2 | 16.5 | 264.8 | 16.2 | 269.6 | 16.5 | 271.6 | 16.4 | 103.4 | 61.5 |

| High | 241.3 | 15.7 | 254.5 | 15.7 | 284.7 | 15.6 | 301.4 | 15.5 | 302.9 | 15.5 | 304.5 | 15.4 | 309.8 | 15.6 | 312.5 | 15.5 | 71.2 | 29.5 |

*Significant trend in each subgroup across the survey years (p<0.0001; test for trend).

†Values adjusted for age, sex and urbanisation.

‡Absolute difference (AD) between 1991 and 2011.

§Relative change (RC) between 1991 and 2011.

Trends in food sources of daily cholesterol intake by age, sex and urbanisation

We further investigated food sources of daily cholesterol intake by age, sex and urbanisation in Chinese adults from 1991 to 2011, and representative data in 1991, 2000 and 2011 were shown in tables 3–5.

Table 3.

Food sources of daily cholesterol intake (mg/day) by age among Chinese adults younger than 60 years from 1991 to 2011*,†

| 1991 |

2000 |

2011 |

|||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SE | Rank | Total, % | Cumulative, % | Mean | SE | Rank | Total, % | Cumulative, % | Mean | SE | Rank | Total, % | Cumulative, % | |

| Age group (18–39) | |||||||||||||||

| Eggs | 71.9 | 14.4 | 1 | 43.4 | 43.4 | 122.9 | 14.5 | 1 | 53.5 | 53.5 | 141.5 | 14.5 | 1 | 53.7 | 53.7 |

| Pork | 44.8 | 6.0 | 2 | 27.1 | 70.5 | 51.9 | 6.0 | 2 | 22.6 | 76.1 | 57.3 | 6.0 | 2 | 21.8 | 75.5 |

| Fish and shellfish | 16.4 | 3.6 | 3 | 9.9 | 80.4 | 19.2 | 3.6 | 3 | 8.4 | 84.5 | 22.0 | 3.6 | 3 | 8.3 | 83.8 |

| Animal fat | 12.0 | 2.4 | 4 | 7.2 | 87.6 | 8.2 | 2.4 | 5 | 3.6 | 88.1 | 3.4 | 2.3 | 7 | 1.3 | 86.1 |

| Organ meats | 8.8 | 1.6 | 5 | 5.3 | 92.9 | 7.7 | 1.6 | 6 | 3.3 | 91.5 | 6.4 | 1.1 | 6 | 2.4 | 87.5 |

| Poultry | 4.3 | 1.0 | 6 | 2.6 | 95.5 | 6.5 | 1.0 | 7 | 2.8 | 94.3 | 8.3 | 1.0 | 5 | 3.2 | 90.7 |

| Beef | 4.1 | 1.6 | 7 | 2.5 | 98.0 | 8.4 | 1.6 | 4 | 3.7 | 98.0 | 12.1 | 1.6 | 4 | 4.6 | 95.3 |

| Milks | 2.1 | 0.9 | 8 | 1.3 | 99.3 | 2.3 | 0.9 | 8 | 1.0 | 98.9 | 3.2 | 0.9 | 8 | 1.2 | 96.5 |

| Age group (40–59) | |||||||||||||||

| Eggs | 77.7 | 13.9 | 1 | 46.4 | 46.4 | 128.0 | 13.8 | 1 | 55.4 | 55.4 | 155.7 | 13.7 | 1 | 57.8 | 57.8 |

| Pork | 44.7 | 6.2 | 2 | 26.7 | 73.1 | 50.9 | 6.2 | 2 | 22.0 | 77.4 | 56.8 | 6.2 | 2 | 21.1 | 78.9 |

| Fish and shellfish | 16.6 | 4.5 | 3 | 9.9 | 83.0 | 21.0 | 4.5 | 3 | 9.1 | 86.5 | 25.4 | 4.5 | 3 | 9.4 | 88.3 |

| Animal fat | 10.3 | 2.2 | 4 | 6.2 | 89.2 | 6.8 | 2.2 | 6 | 2.9 | 89.4 | 2.1 | 2.2 | 8 | 0.8 | 89.1 |

| Organ meats | 7.6 | 1.2 | 5 | 4.5 | 93.7 | 7.3 | 1.1 | 5 | 3.2 | 92.6 | 6.2 | 1.6 | 5 | 2.3 | 91.4 |

| Poultry | 3.6 | 1.6 | 6 | 2.2 | 95.9 | 7.9 | 1.6 | 4 | 3.4 | 96.0 | 9.0 | 1.6 | 4 | 3.4 | 94.8 |

| Beef | 3.4 | 1.0 | 7 | 2.0 | 97.9 | 5.5 | 0.9 | 7 | 2.4 | 98.4 | 5.5 | 0.9 | 6 | 2.0 | 96.8 |

| Milks | 2.7 | 1.0 | 8 | 1.6 | 99.5 | 2.8 | 1.0 | 8 | 1.2 | 99.6 | 3.2 | 0.9 | 7 | 1.2 | 98.0 |

*Significant trend in each subgroup across the survey years (p<0.0001; test for trend).

†Values adjusted for age, sex and urbanisation.

Table 4.

Food sources of daily cholesterol intake (mg/day) by sex among Chinese adults younger than 60 years from 1991 to 2011*,†

| 1991 |

2000 |

2011 |

|||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SE | Rank | Total, % | Cumulative, % | Mean | SE | Rank | Total, % | Cumulative, % | Mean | SE | Rank | Total, % | Cumulative, % | |

| Male | |||||||||||||||

| Eggs | 78.1 | 14.8 | 1 | 43.8 | 43.8 | 127.2 | 14.7 | 1 | 53.3 | 53.3 | 149.1 | 14.6 | 1 | 53.9 | 53.9 |

| Pork | 48.9 | 6.6 | 2 | 27.4 | 71.2 | 54.6 | 6.6 | 2 | 22.9 | 76.2 | 60.3 | 6.6 | 2 | 21.8 | 75.7 |

| Fish and shellfish | 18.7 | 4.3 | 3 | 10.5 | 81.7 | 21.4 | 4.3 | 3 | 9.0 | 85.2 | 25.3 | 4.3 | 3 | 9.1 | 84.8 |

| Animal fat | 11.9 | 2.4 | 4 | 6.7 | 88.4 | 7.8 | 2.4 | 6 | 3.3 | 88.5 | 3.5 | 2.4 | 7 | 1.3 | 86.1 |

| Organ meats | 9.4 | 1.4 | 5 | 5.3 | 93.7 | 8.6 | 1.4 | 5 | 3.6 | 92.1 | 7.0 | 1.4 | 6 | 2.5 | 88.6 |

| Poultry | 4.4 | 1.7 | 6 | 2.5 | 96.2 | 9.1 | 1.7 | 4 | 3.8 | 95.9 | 11.4 | 1.7 | 4 | 4.1 | 92.7 |

| Beef | 4.3 | 1.2 | 7 | 2.4 | 98.6 | 7.0 | 1.2 | 7 | 2.9 | 98.8 | 8.4 | 1.1 | 5 | 3.0 | 95.7 |

| Milks | 2.2 | 0.8 | 8 | 1.2 | 99.8 | 2.3 | 0.8 | 8 | 1.0 | 99.8 | 2.8 | 0.8 | 8 | 1.0 | 96.7 |

| Female | |||||||||||||||

| Eggs | 72.9 | 13.2 | 1 | 46.2 | 46.2 | 123.3 | 13.1 | 1 | 54.8 | 54.8 | 145.3 | 13.1 | 1 | 57.0 | 57.0 |

| Pork | 40.8 | 5.6 | 2 | 25.8 | 72.0 | 47.2 | 5.6 | 2 | 21.0 | 75.8 | 54.7 | 5.6 | 2 | 21.5 | 78.5 |

| Fish and shellfish | 16.0 | 4.0 | 3 | 10.1 | 82.1 | 19.1 | 3.9 | 3 | 8.5 | 84.3 | 22.6 | 3.9 | 3 | 8.9 | 87.4 |

| Animal fat | 10.5 | 2.1 | 4 | 6.7 | 88.8 | 7.3 | 2.1 | 5 | 3.3 | 87.6 | 2.0 | 1.1 | 8 | 0.8 | 88.2 |

| Organ meats | 7.0 | 1.2 | 5 | 4.4 | 93.2 | 7.0 | 1.2 | 6 | 3.1 | 90.7 | 6.1 | 1.2 | 5 | 2.4 | 90.6 |

| Poultry | 3.6 | 1.5 | 6 | 2.3 | 95.5 | 8.2 | 1.5 | 4 | 3.7 | 94.4 | 9.2 | 1.5 | 4 | 3.6 | 94.2 |

| Beef | 3.0 | 0.8 | 7 | 1.9 | 97.4 | 5.0 | 0.8 | 7 | 2.2 | 96.6 | 5.4 | 0.8 | 6 | 2.1 | 96.3 |

| Milks | 2.8 | 1.1 | 8 | 1.8 | 99.2 | 3.0 | 1.1 | 8 | 1.3 | 97.9 | 3.7 | 1.1 | 7 | 1.4 | 97.7 |

*Significant trend in each subgroup across the survey years (p<0.0001; test for trend).

†Values adjusted for age, sex and urbanisation.

Table 5.

Food sources of daily cholesterol intake (mg/day) by urbanisation among Chinese adults younger than 60 years from 1991 to 2011*,†

| 1991 |

2000 |

2011 |

|||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SE | Rank | Total, % | Cumulative, % | Mean | SE | Rank | Total, % | Cumulative, % | Mean | SE | Rank | Total, % | Cumulative, % | |

| Low urbanisation | |||||||||||||||

| Eggs | 41.6 | 14.2 | 1 | 40.5 | 40.5 | 90.1 | 14.2 | 1 | 56.5 | 56.5 | 130.1 | 14.1 | 1 | 60.5 | 60.5 |

| Pork | 35.6 | 7.9 | 2 | 34.6 | 75.1 | 40.5 | 7.8 | 2 | 25.4 | 81.9 | 49.1 | 7.9 | 2 | 22.9 | 83.4 |

| Fish and shellfish | 9.8 | 3.0 | 3 | 9.5 | 84.6 | 12.3 | 3.0 | 3 | 7.7 | 89.6 | 15.6 | 3.0 | 3 | 7.3 | 90.7 |

| Animal fat | 7.6 | 3.6 | 4 | 7.4 | 92.0 | 6.6 | 3.6 | 4 | 4.1 | 93.7 | 3.6 | 3.6 | 5 | 1.7 | 92.4 |

| Organ meats | 3.6 | 1.0 | 5 | 3.5 | 95.5 | 3.4 | 1.0 | 6 | 2.1 | 95.8 | 3.6 | 1.0 | 6 | 1.6 | 94.0 |

| Poultry | 2.7 | 1.8 | 6 | 2.6 | 98.1 | 4.3 | 1.3 | 5 | 2.7 | 98.5 | 5.1 | 1.3 | 4 | 2.4 | 96.4 |

| Beef | 1.0 | 0.7 | 7 | 1.0 | 99.1 | 1.7 | 0.7 | 7 | 1.1 | 99.6 | 3.1 | 0.7 | 7 | 1.4 | 97.8 |

| Milks | 0.2 | 0.2 | 8 | 0.2 | 99.3 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 8 | 0.1 | 99.7 | 0.4 | 0.2 | 8 | 0.2 | 98.0 |

| Medium urbanisation | |||||||||||||||

| Eggs | 75.9 | 13.6 | 1 | 46.3 | 43.6 | 120.5 | 13.5 | 1 | 51.3 | 51.3 | 151.4 | 13.6 | 1 | 55.7 | 53.7 |

| Pork | 47.5 | 7.8 | 2 | 27.1 | 73.4 | 58.9 | 7.7 | 2 | 25.1 | 76.4 | 62.6 | 7.8 | 2 | 23.1 | 78.8 |

| Fish and shellfish | 15.1 | 4.6 | 3 | 9.0 | 82.4 | 18.6 | 4.6 | 3 | 7.9 | 84.3 | 22.0 | 4.6 | 3 | 8.1 | 86.9 |

| Animal fat | 11.9 | 2.6 | 4 | 7.1 | 89.5 | 9.3 | 2.6 | 4 | 4.0 | 88.3 | 3.5 | 2.5 | 7 | 1.3 | 88.2 |

| Organ meats | 6.9 | 1.5 | 5 | 4.1 | 93.6 | 8.1 | 1.5 | 5 | 3.4 | 91.7 | 6.7 | 1.5 | 6 | 2.5 | 90.7 |

| Poultry | 3.4 | 1.3 | 7 | 2.0 | 95.6 | 7.2 | 1.8 | 6 | 3.1 | 94.8 | 9.3 | 1.8 | 4 | 3.4 | 94.1 |

| Beef | 4.7 | 1.3 | 6 | 2.8 | 98.4 | 6.1 | 1.3 | 7 | 2.6 | 97.4 | 7.6 | 1.2 | 5 | 2.8 | 96.9 |

| Milks | 1.4 | 0.7 | 8 | 0.8 | 99.2 | 1.5 | 0.7 | 8 | 0.6 | 98.0 | 2.5 | 0.7 | 8 | 0.9 | 97.8 |

| High urbanisation | |||||||||||||||

| Eggs | 119.1 | 17.8 | 1 | 49.4 | 49.4 | 156.1 | 17.7 | 1 | 51.8 | 51.8 | 164.0 | 17.6 | 1 | 52.5 | 52.5 |

| Pork | 61.7 | 6.4 | 2 | 25.6 | 75.0 | 65.7 | 6.3 | 2 | 21.8 | 73.6 | 66.6 | 6.3 | 2 | 21.3 | 73.8 |

| Fish and shellfish | 18.6 | 4.7 | 3 | 7.7 | 82.7 | 25.3 | 4.7 | 3 | 8.4 | 82.0 | 29.6 | 4.7 | 3 | 9.5 | 83.3 |

| Animal fat | 12.0 | 2.3 | 5 | 5.0 | 87.7 | 7.5 | 2.3 | 7 | 2.5 | 84.5 | 2.1 | 2.3 | 8 | 0.7 | 84.0 |

| Organ meats | 14.2 | 2.1 | 4 | 5.9 | 93.6 | 12.8 | 2.1 | 5 | 4.2 | 88.7 | 7.8 | 3.5 | 6 | 2.5 | 86.5 |

| Poultry | 6.2 | 2.2 | 6 | 2.6 | 96.2 | 14.6 | 2.2 | 4 | 4.8 | 93.5 | 15.1 | 2.2 | 4 | 4.8 | 91.3 |

| Beef | 5.0 | 1.3 | 7 | 2.0 | 98.2 | 10.2 | 1.3 | 6 | 3.4 | 96.9 | 10.6 | 1.3 | 5 | 3.4 | 94.7 |

| Milks | 3.7 | 1.1 | 8 | 1.5 | 99.7 | 4.2 | 1.1 | 8 | 1.4 | 98.3 | 6.1 | 1.1 | 7 | 1.9 | 96.6 |

*Significant trend in each subgroup across the survey years (p<0.0001; test for trend).

†Values adjusted for age, sex and urbanisation.

In both age groups, daily cholesterol intake levels from the majority of food items showed increasing trends over time (p<0.0001), except for animal fat and organ meats (table 3). Moreover, eggs, pork, fish and shellfish in that order remained the top three sources of dietary cholesterol in 1991, 2000 and 2011, cumulatively supplying 80.4–88.3% cholesterol/day. Cholesterol intakes from milks were negligible in each survey year, approximately accounting for 1.0% of total dietary cholesterol. Cholesterol amounts from animal fat were more than 10.0 mg/day in 1991, which ranked fourth in all food sources, but declined in 2000 and became slight in 2011. In particular, the quantity of cholesterol from beef was 4.1 mg/day in 1991 and increased to 12.1 mg/day in 2011, which rose to the fourth food source in 2000 and 2011, in adults aged 18–39 years. Conversely, poultry was the fourth major source of daily cholesterol intake in 2000 and 2011 in adults aged 40–59 years.

Likewise, daily cholesterol intakes from major food items showed increasing trends over time (p<0.0001), whereas those from animal fat and organ meats displayed decreasing trends (p<0.0001) in male and female adults (table 4). The most significant food sources were eggs, pork, fish and shellfish in that order in each survey year, from which the cumulative proportion of cholesterol ranged from 81.7% to 87.4% daily. The insignificant food source of cholesterol was milks during the study periods, which provided 2.2–2.8 and 2.8–3.7 mg/day cholesterol in males and females, respectively. Animal fat was the main source and ranked fourth in all foods in 1991; however, it acted as an unimportant food source of cholesterol in 2011. In contrast, daily cholesterol intakes from poultry increased from 4.4 and 3.6 mg/day in 1991 to 11.4 and 9.2 mg/day in 2011 in males and females, respectively, which ranked fourth in 2000 and 2011.

In the stratified analysis by urbanisation (table 5), daily cholesterol intakes from major food items also showed increasing trends over time (p<0.0001), whereas the trends in those from animal fat and organ meats were opposite (p<0.0001), especially the quantity of cholesterol from animal fat which dropped from 7.6, 11.9 and 12.0 mg/day in 1991 to 3.6, 3.5 and 2.1 mg/day in 2011 for adults from low, medium and high urbanisation areas, respectively. The top three food sources of daily cholesterol intake were eggs, pork, fish and shellfish in that order in any urbanised area in each survey year. Poultry was a key source of daily cholesterol in 2011 in low, medium and high urbanisation areas, although it supplied lower cholesterol in 1991. Interestingly, the quantity of cholesterol daily from beef and milks were most inappreciable in adults from a low urbanisation area across the survey years, while the most insignificant food source of cholesterol was milks in medium and high urbanisation areas across the survey years.

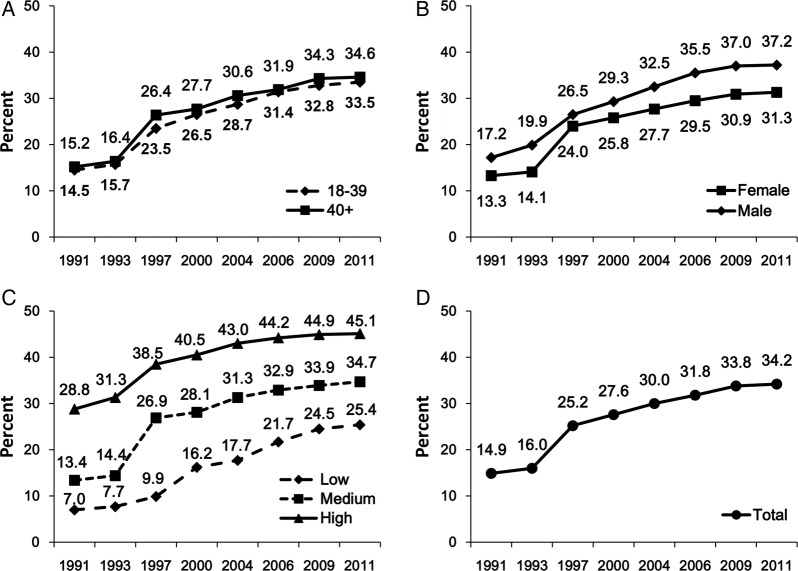

Trends in proportions of subjects with excessive cholesterol intake daily

The proportions of Chinese adults who consumed more than 300 mg/day cholesterol increased from 14.9% in 1991 to 34.2% in 2011 (figure 1). Furthermore, the increasing trends in proportions of adults with more than 300 mg/day cholesterol intake in different age (18–39 and 40–59 years), sex and urbanisation groups across the survey years were significant (p<0.0001). The most striking proportions were observed in adults of the high urbanisation area, which was 28.8% in 1991 and increased to 45.1% in 2011.

Figure 1.

Secular trends in the proportion of Chinese adults having more than 300 mg/day cholesterol intake in the different age (A), sex (B) and urbanisation (C) groups, as well as total adults (D), China Health and Nutrition Survey 1991–2011.

Discussion

Mounting evidence identified that cardiovascular disease is the leading cause of death, and dietary cholesterol is one of the key risk factors for cardiovascular disease by altering plasma cholesterol.16 Thus, monitoring dietary cholesterol intake status is informative for prediction of dietary habits, compliance with nutritional recommendations, cardiovascular disease and other chronic diseases. However, the related longitudinal studies using large samples in China are scarce. This study evaluated the changes in the amount of daily cholesterol intake and identified food sources of dietary cholesterol in Chinese adults during the 20-year period (1991–2011) by using the data from the CHNS cohort, which includes nine waves and reflects the changes in demographics, economics, nutrition and health in China in the past few decades. Although mean dietary cholesterol consumption was stable in adults worldwide between 1990 and 2010 (global change +7 mg/day (−1 to 15)),17 our findings showed a 1.6-fold difference in mean daily cholesterol intake in Chinese adults from 1991 (165.8 mg/day) to 2011 (266.3 mg/day). Moreover, mean cholesterol intake in Chinese adults in 2000 (230.4 mg/day) and later survey years remained higher than the mean global consumption (228 mg/day) in 2010 for adults.17 Participants in different age, sex and urbanisation groups steadily consumed more cholesterol over time. As a result, the increasing trends in the proportion of participants who consumed more than 300 mg/day cholesterol across the survey years were significant. The leading sources of cholesterol were eggs, pork, fish and shellfish in that order; conversely, cholesterol from milks remained negligible, whereas poultry was gradually becoming a major contributor. All these results indicated that Chinese adults consumed increasingly high cholesterol mainly from eggs, pork, fish and shellfish, and deviated from dietary reference intakes.

In Europe, the reported daily cholesterol intakes of Spanish adults in 2001 (440.87 and 359.14 mg for men and women, respectively) were higher than those indicated in the nutritional objectives for the Spanish population (<300 mg/day).18 Similar amounts of cholesterol were also found in Greece.19 During the past 20 years, China has experienced remarkable socioeconomic development, with the mean income rising by several folds. The average amount of daily cholesterol intake in Chinese healthy adults was 430.7 mg in a survey conducted in a highly urbanised district of Tianjin from 2010 to 2011.20 This report indicated that the lifestyle of people in the developed areas has changed dramatically. The nutrition-related lifestyle has led to increased intakes of cholesterol and other nutrients. Another regional study in Guangxi, province of China, found that the mean dietary cholesterol was 199.2 mg/day in Han Chinese,21 highly less than that in Tianjin,20 which implied regional differences exist in China. Very few data on the changes in cholesterol intake over the past few decades were available. Our study conducted a comprehensive and longitudinal survey of daily cholesterol intake in Chinese adults covering a wide variety of nine provinces and autonomous regions from northern to southern parts of China between 1991 and 2011, which was a nationally representative sample. Although the mean daily cholesterol intake levels of participants from different age (18–39 and 40–59 years) and sex groups in each survey year were less than the recommended level (300 mg/day), these values steadily increased by about 100 mg/day from 1991 to 2011. Compared to the Nutrition and Health Survey in Taiwan 1993–1996 to 2005–2008,10 where the mean cholesterol intake in men aged 19–30 years exceeded 400 mg and that of men aged 31–64 years was about 300 mg, while the intake of cholesterol in women aged 31–64 years was less than 300 mg in the 1993–1996 survey, in the 2005–2008 survey, the mean cholesterol intake of men aged both 19–30 and 31–64 years exceeded 400 mg and that of women was about 300 mg; moreover, about 80% of men and 45% of women had daily intakes of cholesterol greater than 400 mg. This study in China showed that cholesterol intake levels between young and old adults were almost comparable across the survey years, whereas, similar to the Taiwanese study, females most likely consumed less cholesterol than males, suggesting different dietary habits and lifestyles between men and women. In addition, our data displayed that adults residing in a high urbanisation area had extremely high cholesterol intake over time, which was greater than 300 mg/day from 2000, and there was the most significant increment in cholesterol intake in a low urbanised area from 1991 to 2011, indicating diverse food choices and affluent living in a high urbanised area, and enormous influences of socioeconomic transitions on dietary behaviours in a low urbanised area. As a whole, the mean daily cholesterol intake in Chinese adults was lower than that in Taiwanese adults during corresponding periods.10 For these differences, demographic, economic and dietary characteristics may play a role. However, issues of concern remained in China; the proportions of deviation from cholesterol reference intake significantly increased over time, with around 37.2% males and 31.3% females having a daily cholesterol intake of more than 300 mg in 2011.

In terms of food sources of cholesterol among Chinese adults from 1991 to 2011, the highest ranking sources remained eggs, pork, fish and shellfish in each subgroup. These top three food items increasingly supplied cholesterol during 1991–2011 and contributed more than 80% of the total cholesterol together. These findings were consistent with the main cholesterol sources for adults in Taiwan,10 possibly due to the similar eating habits between the Chinese and Taiwanese. Different from the observations among US adults from the 1989–1991 to 1994–1996 Continuing Survey of Food Intakes by Individuals,22 there were remarkable changes between surveys in food sources identified for cholesterol in Chinese adults from 1991 to 2011. Cholesterol supplied by animal fat declined and was insignificant in 2011 in most of the subgroups (except for low urbanised regions), whereas cholesterol being of poultry origin increased and was considerable in 2011. The plausible explanation was that some positive dietary and behavioural changes have appeared, along with the dramatic increase in the availability of new food choices in recent times. When consuming meat products, people are encouraged to select lean or low-fat meat and poultry, and avoid the products made from animal fats.23 From a comparison of the food group distribution for cholesterol in this study (1991–2011) to that in other Asian countries, such as Korea (2000)24 and Japan (1994),25 and the USA (2003–2006),26 several interesting features were observed, including that the three top food sources in Chinese adults were quite similar to that in Koreans aged 30–85 years; in contrast to Chinese and US adults, milk was a major contributor in middle-aged Japanese as well as Koreans; distinct from China and Korea, pork was a negligible source in Japan and the USA, where pork was mostly replaced with various fish/shellfish and poultry/beef, respectively; poultry gradually became a main source over time in China but was insignificant in Japan and Korea; similar to Koreans, beef became an important source in young Chinese adults in 2000 and 2011; eggs ranked first as a source of cholesterol in each country; almost half of the total cholesterol intake was derived from eggs in Chinese adults in our study; and organ meats were a unique source of cholesterol in China. Taken together, these differences may be attributable to geographic location, food supply, dietary habits and economic levels.

The study is not without limits. As with all studies based on dietary survey, the accuracy of the intake estimates was limited by the accuracy of recalls provided by survey participants and the specificity to which the reported foods were mapped in the dietary recall records. In addition, food grouping can have a major influence on the ranked order of dietary sources; thus, caution is advised when comparing these data with previous reports,24–26 if there were differences in the level of aggregation (such as the number of food groups) or disaggregation procedures used to include ingredients in food groups.

Conclusions

In conclusion, the amounts of daily cholesterol intake in Chinese adults steadily increased from 1991 to 2011, as did the proportion of participants with a greater cholesterol intake than 300 mg/day. Adults need to pay attention to the intake in the food groups of eggs, pork, fish and shellfish and ensure that it is appropriate. On the basis of all these findings, we recommend strengthening public nutrition education by developing leaflets, posters and slides. As the eating behaviour and dietary patterns may change, the governments and nutrition societies should keep revising dietary guidelines and daily food guides to encourage population health.

Footnotes

Contributors: CS played a role in analysing the data and revision of the article; XJ contributed to the writing and revision of the paper; ZW made a substantial contribution to the conception and design of the work; HW and BZ contributed to a critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content.

Funding: The study was funded by the National Institute for Nutrition and Food Safety, China Center for Disease Control and Prevention, Carolina Population Center (5 R24 HD050 924); the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, the NIH (R01-HD30880, DK056350, R24 HD050924, and R01-HD38700); and the Fogarty International Center, NIH, for providing financial support for the collection and analysis of the CHNS data from 1989 to 2011 and the future surveys. This study is also funded by the Danone Institute China Diet Nutrition Research and Communication Grant (DIC2013-02) in 2013; and supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No.81172666) and Youth Foundation of Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention (No.2013B103).

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: The research was reviewed and approved by the Institute Review Board of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Oza-Frank R, Cheng YJ, Narayan KM et al. . Trends in nutrient intake among adults with diabetes in the United States: 1988–2004. J Am Diet Assoc 2009;109:1173–8. 10.1016/j.jada.2009.04.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ramazauskiene V, Petkeviciene J, Klumbiene J et al. . Diet and serum lipids: changes over socio-economic transition period in Lithuanian rural population. BMC Public Health 2011;11:447 10.1186/1471-2458-11-447 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Du W, Su C, Wang H et al. . Is density of neighbourhood restaurants associated with BMI in rural Chinese adults? A longitudinal study from the China Health and Nutrition Survey. BMJ Open 2014;4:e004528 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-004528 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yu L, Morishima C, Ioannou GN. Dietary cholesterol intake is associated with progression of liver disease in patients with chronic hepatitis C: analysis of the hepatitis C antiviral long-term treatment against cirrhosis trial. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2013;11:1661–6.e1–3 10.1016/j.cgh.2013.05.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Larsson SC, Virtamo J, Wolk A. Dietary fats and dietary cholesterol and risk of stroke in women. Atherosclerosis 2012;221:282–6. 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2011.12.043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Houston DK, Ding J, Lee JS et al. . Dietary fat and cholesterol and risk of cardiovascular disease in older adults: the Health ABC Study. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis 2011;21:430–7. 10.1016/j.numecd.2009.11.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brownawell AM, Falk MC. Cholesterol: where science and public health policy interest. Nutr Rev 2010;68:355–64. 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2010.00294.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen J, Gao J. The Chinese total diet study in 1990. Part II. Nutrients. J AOAC Int 1993;76:1206–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.de Abreu D, Guessous I, Gaspoz JM et al. . Compliance with the Swiss Society for Nutrition's dietary recommendations in the population of Geneva, Switzerland: a 10-year trend study (1999–2009). J Acad Nutr Diet 2014;114:774–80. 10.1016/j.jand.2013.07.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wu SJ, Pan WH, Yeh NH et al. . Trends in nutrient and dietary intake among adults and the elderly: from NAHSIT 1993–1996 to 2005–2008. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr 2011;20:251–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Su C, Wang H, Wang Z et al. . Status and trend of fat and cholesterol intake among Chinese middle and old aged residents in 9 provinces from 1991 to 2009. Wei Sheng Yan Jiu 2013;42:72–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang B, Zhai FY, Du SF et al. . The China Health and Nutrition Survey, 1989–2011. Obes Rev 2014;15(Suppl 1):2–7. 10.1111/obr.12119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang Z, Zhang B, Wang H et al. . Study on the multilevel and longitudinal association between meat consumption and changes in body mass index, body weight and risk of incident overweight among Chinese adults. Clin J Epidemiol 2013;34:1–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang HJ, Wang ZH, Zhang JG et al. . Trends in dietary fiber intake in Chinese aged 45 years and above, 1991–2011. Eur J Clin Nutr 2014;68:619–22. 10.1038/ejcn.2014.24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jones-Smith JC, Popkin BM. Understanding community context and adult health changes in China: development of an urbanicity scale. Soc Sci Med 2010;71:1436–46. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.07.027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim DS, Burt AA, Ranchalis JE et al. . Novel gene-by-environment interactions: APOB and NPC1L1 variants affect the relationship between dietary and total plasma cholesterol. J Lipid Res 2013;54:1512–20. 10.1194/jlr.P035238 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Renata M, Shahab K, Peilin S et al. . Global, regional, and national consumption levels of dietary fats and oils in 1990 and 2010: a systematic analysis including 266 country-specific nutrition surveys. BMJ 2014;348:g2272 10.1136/bmj.g2272 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Capita R, Alonso-Calleja C. Intake of nutrients associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular disease in a Spanish population. Int J Food Sci Nutr 2003;54:57–75. 10.1080/0963748031000062001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kafatos A, Verhagen H, Moschandreas J et al. . Mediterranean diet of Crete: foods and nutrient content. J Am Diet Assoc 2000;100:1487–93. 10.1016/S0002-8223(00)00416-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bian S, Gao Y, Zhang M et al. . Dietary nutrient intake and metabolic syndrome risk in Chinese adults: a case-control study. Nutr J 2013;12:106 10.1186/1475-2891-12-106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yin R, Pan S, Chen H et al. . Diet, alcohol consumption, and serum lipid levels of the middle-aged and elderly in the Guangxi Bai Ku Yao and Han populations. Alcohol 2008;42:219–29. 10.1016/j.alcohol.2008.01.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cotton PA, Subar AF, Friday JE et al. . Dietary sources of nutrients among US adults, 1994 to 1996. J Am Diet Assoc 2004;104:921–30. 10.1016/j.jada.2004.03.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pan WH, Wu HJ, Yeh CJ et al. . Diet and health trends in Taiwan: comparison of two nutrition and health surveys from 1993–1996 and 2005–2008. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr 2011;20:238–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim J, Kim Y, Ahn Y et al. . Contribution of specific foods to fat, fatty acids, and cholesterol in the development of a food frequency questionnaire in Koreans. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr 2004;13:265–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tokudome Y, Imaeda N, Ikeda M et al. . Foods contributing to absolute intake and variance in intake of fat, fatty acids and cholesterol in middle-aged Japanese. J Epidemiol 1999;9:78–90. 10.2188/jea.9.78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.O'Neil CE, Keast DR, Fulgoni VL III et al. . Food sources of energy and nutrients among adults in the US: NHANES 2003–2006. Nutrition 2012;4:2097–120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]