Abstract

Objective

Lack of consensus on the definition of mental health has implications for research, policy and practice. This study aims to start an international, interdisciplinary and inclusive dialogue to answer the question: What are the core concepts of mental health?

Design and participants

50 people with expertise in the field of mental health from 8 countries completed an online survey. They identified the extent to which 4 current definitions were adequate and what the core concepts of mental health were. A qualitative thematic analysis was conducted of their responses. The results were validated at a consensus meeting of 58 clinicians, researchers and people with lived experience.

Results

46% of respondents rated the Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC, 2006) definition as the most preferred, 30% stated that none of the 4 definitions were satisfactory and only 20% said the WHO (2001) definition was their preferred choice. The least preferred definition of mental health was the general definition of health adapted from Huber et al (2011). The core concepts of mental health were highly varied and reflected different processes people used to answer the question. These processes included the overarching perspective or point of reference of respondents (positionality), the frameworks used to describe the core concepts (paradigms, theories and models), and the way social and environmental factors were considered to act. The core concepts of mental health identified were mainly individual and functional, in that they related to the ability or capacity of a person to effectively deal with or change his/her environment. A preliminary model for the processes used to conceptualise mental health is presented.

Conclusions

Answers to the question, ‘What are the core concepts of mental health?’ are highly dependent on the empirical frame used. Understanding these empirical frames is key to developing a useful consensus definition for diverse populations.

Keywords: MENTAL HEALTH, mental illness, social determinants of health, human rights, agency, primary health care

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Our study identifies a major obstacle for integrating mental health initiatives into global health programmes and health service delivery, which is a lack of consensus on a definition, and initiates a global, interdisciplinary and inclusive dialogue towards a consensus definition of mental health.

Despite the limitations of a small sample size and response saturation, our sample of global experts was able to demonstrate dissatisfaction with current definitions of mental health and significant agreement among subcomponents, specifically factors beyond the ‘ability to adapt and self-manage’, such as ‘diversity and community identity’ and creating distinct definitions, ‘one for individual and a parallel for community and society’.

This research demonstrates how experts in the field of mental health determine the core concepts of mental health, presenting a model of how empirical discourses shape definitions of mental health.

We propose a transdomain model of health to inform the development of a comprehensive definition capturing all of the subcomponents of health: physical, mental and social health.

Our study discusses the implications of the findings for research, policy and practice in meeting the needs of diverse populations.

Introduction

A major obstacle for integrating mental health initiatives into global health programmes and primary healthcare services is lack of consensus on a definition of mental health.1–3 There is little agreement on a general definition of ‘mental health’4 and currently there is widespread use of the term ‘mental health’ as a euphemism for ‘mental illness’.5 Mental health can be defined as the absence of mental disease or it can be defined as a state of being that also includes the biological, psychological or social factors which contribute to an individual’s mental state and ability to function within the environment.4 6–11 For example, the WHO12 includes realising one's potential, the ability to cope with normal life stresses and community contributions as core components of mental health. Other definitions extend beyond this to also include intellectual, emotional and spiritual development,13 positive self-perception, feelings of self-worth and physical health,11 14 and intrapersonal harmony.8 Prevention strategies may aim to decrease the rates of mental illness but promotion strategies aim at improving mental health. The possible scope of promotion initiatives depends on the definition of mental health.

The purpose of this paper is to begin a global, interdisciplinary, interactive and inclusive series of dialogues leading to a consensus definition of mental health. It has been stimulated and informed by a recent debate about the need to redefine the term health. Huber et al15 emphasised that health should encompass an individual's “ability to adapt and to self-manage” in response to challenges, rather than achieving “a state of complete wellbeing” as stated in current WHO6 12 definitions. They also argued that a new definition must consider the demographics of stakeholders involved and future advances in science.15 Responses to the article suggested the process of reconceptualising health be extended “beyond the esoteric world of academia and the pragmatic world of policy”16 to include a “much wider lens to the aetiology of health”17 along with patients and lay members of the public. Huber et al's15 definition of health could include mental health but it is not clear that this would be satisfactory to patients, practitioners or researchers. We aimed to compare the satisfaction of mental health specialists, patients and the public with Huber et al’s definition and other currently used definitions of mental health. We also asked them what they considered to be the core components of mental health.

Methods

Participants and procedures

A pool of 25 researchers in mental health was identified through literature/internet searches to capture expertise in (1) ‘community mental health’ and ‘public mental health’, (2) ‘human rights’ and ‘global mental health’, (3) ‘positive mental health’ and ‘resilience’, (4) ‘recovery’ and ‘mental health’, and (5) ‘natural selection’ and ‘evolutionary origins’ of ‘mental health’. Each of these five areas was assigned to an author with expertise in that area who then conducted a series of literature/internet searches using the key terms listed above. Proposed participants were identified based on their expert contributions, such as published papers, presentations, community outreach, and other evidence of work in their field that had implications for mental health. Each author presented their list to the research team which then narrowed the number to 5 per category for a total of 25 initial participants. An additional 31 individuals were added, which included people with lived experience of mental illness as well as the mentors of the Social Aetiology of Mental Illness (SAMI) Training Programme (funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research and includes a multidisciplinary group of experts with diverse interests, including biological, social and psychological sciences); all of these participants were identified through the SAMI/Centre for Addiction and Mental Health network. Fifty-six participants were sent the survey in the first round. Two subsequent rounds were completed using a snowballing technique: each person in round 1 was asked to indicate up to three other people they thought should receive the survey, which was then distributed to those identified individuals. This was repeated in round 2.

The ‘What is Mental Health?’ survey was created and distributed electronically using the SurveyMonkey platform. Respondents were asked to describe their areas of expertise, and list or describe the core concepts of mental health. Respondents ranked four definitions (without citations) of mental health12 15 18 (McKenzie K. Community definition of Mental Health. What Is Mental Health Survey. Centre for Addiction and Mental Health, personal communication, 15 January 2014) and a fifth choice of ‘None of the existing definitions are satisfactory’ in order of preference (1=most preferred, 5=least preferred), and could rate multiple definitions as most and/or least preferred (see table 1). Respondents were asked to state, ‘What was missing and why?’ from these definitions.

Table 1.

Current definitions of mental health and participant rank ordering from most to least preferred

| Definition of mental health | Most preferred (%) | Second most preferred (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Public Health Agency of Canada18 “Mental health is the capacity of each and all of us to feel, think, and act in ways that enhance our ability to enjoy life and deal with the challenges we face. It is a positive sense of emotional and spiritual well-being that respects the importance of culture, equity, social justice, interconnections and personal dignity” |

46 |

24 |

| WHO12 “Mental health is defined as a state of well-being in which every individual realizes his or her own potential, can cope with the normal stresses of life, can work productively and fruitfully, and is able to make a contribution to her or his community” |

20 |

26 |

| McKenzie K (personal communication, 2014) “A mentally healthy community offers people the ability to thrive. It is one in which people feel a sense of connectedness and there are also networks which link people from all walks of life to each other. There is a strong community identity but despite this the community is welcoming of diversity. People participate in their community, organize to combat common threats and offer support and aid for those in need” |

14 | 28 |

| Huber et al15 Mental health is the “ability to adapt and self-manage” |

6 | 8 |

| “None of the existing definitions are satisfactory” | 30 | 6 |

Data analysis

Thematic analysis19 was used to evaluate the core concepts of mental health, followed by triangulation (ie, multiple methods, analysts or theory/perspectives) to verify and validate the qualitative data analysis.20

First, multiple analysts with knowledge from different disciplines reviewed the data.20 Our collective areas of expertise encompass the following: animal models of human behaviour; arts; clinical, cognitive, political and social psychology; ecology; education; epidemiology; evolutionary theory; humanities; knowledge translation; measurement; molecular biology; neuroscience; occupational therapy; psychiatry; qualitative and quantitative research; social aetiology of mental illness; toxicology and transcultural health. All transcripts were reviewed by each coder first independently, then collectively, to become familiar with the data and create a mutually agreed on code book using NVivo 10. Codes were organised into themes, and compared and contrasted manually and through NVivo10 coding queries within each major theme and across response items. Initial models derived from the data were created and validated by the multidisciplinary research team.

Second, method triangulation was used to assess the consistency of our findings.20 Preliminary results from the survey were presented and discussed at the 4th Annual Social Aetiology of Mental Illness Conference (20 May 2014) at the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health, University of Toronto (Toronto, Ontario, Canada). Attendees were divided into five focus groups of 10–12 people facilitated by a project leader and 2 trained note takers. The two consecutive 1 h focused discussions used the ORID method (Objective, Reflective, Interpretive and Decisional)21 in order to elicit feedback on the methods and results of the survey. All responses from each of the five groups were transcribed by two recorders and disseminated to the research team for individual and collaborative review.

A second round of data analysis was conducted to validate the results according to key areas of interest and critique reported by the conference participants.

Results

Survey respondents

Fifty-six surveys were distributed in the first round, 28 in the second and 38 in the third. Fifty people completed the survey (rounds 1, 2 and 3 had 32, 12 and 6 respondents, respectively) with a total response rate of 41%. Two-thirds of respondents (66%) were male and one-third were female (34%). Respondents’ current country of residence/employment included Canada (52%), UK (20%), USA (14%), Australia (6%), New Zealand (2%), Brazil (2%), South Africa (2%) and Togo (2%). The majority of respondents (72%) held academic positions at postsecondary institutions and were conducting research in the broad field of mental health. Sixty per cent were also involved in giving advice to mental health services or managing them. Thirty-four per cent of respondents were clinicians.

Survey items

Respondents had diverse expertise (see table 2). Forty-six per cent of respondents rated the Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC)18 definition as their most preferred. However, 30% stated that none were satisfactory. The WHO definition12 was preferred by 20%. The least preferred definition of mental health was the general definition of health adapted from Huber et al15 (see table 1).

Table 2.

Self-reported areas of expertise

| Categories | Examples |

|---|---|

| Social and community health | Health (global, public, promotion, policy); community development; community empowerment; community research; healthcare access; homelessness; immigration; international development; mental health; social inclusion; social support; sociology, research and programme development |

| Human rights: law/ethics/philosophy |

Bioethics; child protection; constitutional law; discrimination/stigma; emancipatory approaches; health equity; human rights; philosophy (science, psychiatry); politics; rights activist, systematic advocacy for service users |

| Positive health: flourishing/positive psychology/recovery/resilience | Flourishing; happiness; peer support; measurement; mental health recovery (advocacy, research, education, family); social inclusion; injury prevention |

| Clinical and biomedical | Biomedical sciences, community based psychosocial rehabilitation; epidemiology; clinical psychiatry/psychology (mood disorders, psychosis), social work, occupational therapy, social psychology; social scientist; chronic health, complex trauma and healing, medicine (end-of-life care/palliative; internal medicine, haematology); HIV; pain, physical disabilities; genetics, outreach, research, youth health, forensics |

| Human positioning: anthropology/culture/evolution/geography/history |

Medical anthropology; population health (Asia, Latin America, Inuit/First Nations, low/middle income countries); evolutionary biology; history (health, social movements); transcultural mental health, urban geography |

| Other | Lived experience; Ehealth; music/dance/performance; event production; innovation; instruction; information and communication technologies |

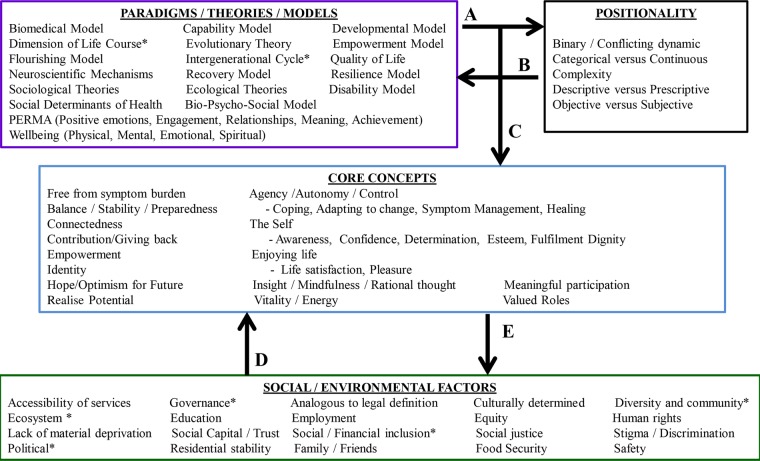

Analysis of the three open-ended items established four major themes—Positionality, Social/Environmental Factors, Paradigms/Theories/Models and the Core Concepts of Mental Health—and five-directional relationships between them (figure 1). Positionality represented the overarching perspective or point-of-reference from which the Core Concepts were derived; whereas Paradigms/Theories/Models represented the theoretical framework within which the Core Concepts were described. Core Concepts represented factors related to the individual; these were distinguishable from the Social/Environmental Factors related to society. Five significant relationships between these themes were established (figure 1). First, respondents’ theoretical framework (Direction A) influenced the overarching point-of-reference they used to describe the core concepts and vice versa (Direction B). Positionality and Paradigms/Theories/Models significantly influenced the core concepts respondents provided and the corresponding descriptions (Direction C). Respondents described how social and environmental factors impacted the core concepts (Direction D) and reciprocally, how the core concepts could influence society (Direction E) (tables 3 and 4). Feedback from the conference focus groups showed support for these five-directional relationships but questioned whether there was evidence for other direct relationships, specifically the impact of Social/Environmental Factors on both Paradigms/Theories/Models and Positionality. A second round of data analysis confirmed these relationships were not explicitly reported by respondents in the survey. Respondents did not discuss how social factors (ie, education or employment) would impact the adoption of a particular paradigm, theory or model (ie, quality of life, evolutionary theory or biomedical model).

Figure 1.

Themes of Positionality, Core Concepts, Social/Environmental Factors, and Paradigms/Theories/Models. *Indicates answers specifically from the third open-ended question asking respondents to state “what is missing” from the definitions provided for ranking.

Table 3.

Theme—Positionality

| Categories | Participant responses |

|---|---|

| Binary/conflicting dynamic | “There are two options represented in the philosophy of mental health. EITHER the absence of mental illness/disease/disorder where that is defined in some either value-laden or value-free way. It may be a simple definition (such as endogenous failure of ordinary doing or harmful dysfunction) or a cluster concept. Health is then its absence. Typically such definitions unify mental and physical health. OR the positive presence of something like flourishing. This underpins approaches to recovery in mental healthcare. It risks equating health and wellbeing” (ie, Directions A and B) |

| “The core concepts of mental health can be organized as a binary and conflicting dynamic that is seeking integration and resolution. On the one hand we have inequity, adversity, trauma, alienation, exclusion, discrimination, stigma, loneliness, stress and mental overwhelm. On the other we have empathy, compassion, dignity, honesty, innovation, peer support, economic equity, social justice, community involvement, mindfulness and recovery” (ie, Directions B–C) | |

| Complexity | “The term means little to me. It is too general and is used, either in the negative or the positive, to indicate such a range of states of being that the term is almost without meaning” |

| “Not located only in the person, but in the interaction between the person and her/his environment” | |

| “Mental health does not exist within the individual, within the brain, within the neurons or within brain chemicals, or within genes. Mental health is both affected by them all but also has effect upon them all. That relation extends also to everything outside the individual: eg, my relations with myself, other individuals, the human world, my immediate environment, my neighbourhood, culture, society, socio-political-economic systems, my environment and the planet we live on” (ie, Direction A; Directions B–C–E) | |

| Dichotomy vs continuum | “The mental wellbeing of the individual as well the ‘health’ of the community in which they exist—social determinants that lead to good or poor mental health—mental health = continuum between mental wellbeing and mental illness—prevention as well as treatment” (ie, Directions B–C–E) |

| “Health and illness belong to distinct continuous dimensions” | |

| Descriptive vs prescriptive (Hume's law*) |

“The key is to shoot for a definition which is in the middle: not to high, so that perfect is required, nor too low…it must have something to do with reasonably good functioning, where reasonably is conceived in terms of the legal standard as average quality. Clearly, you're not mentally well, if you have below-average mental functioning, such that your ability to perform average tasks is impaired” |

| “Moreover, what includes too much. The references to spiritual well-being have got to go, as if non-believers have defective mental health by definition—The third [definition] is good, except for the excessively demanding realization of potential. There's a difference between perfect mental health, and just simply mental health, and too many definitions conflate the two…the offered definition is too much and too contested qua definition (as opposed to theory)” | |

| “I think all of these definitions are too broad. The first, third, and fourth [definitions] look closer to definitions of the good life, or good community, than of health. Lots of things can cause people problems—poverty, vices, social injustice, stupidity—a definition of health should not end up defining these as medical problems” | |

| “There is no definition of positive mental health nor will there be in my view because too many issues are at stake and the most important is the absence of a serious mental illness or other emotional, psycho-physical, and moral problems” | |

| “Most of these [definitions] have too much stuff, creating unattainable goals and sounding like they were crafted by a committee wanting to cover all the bases and to be politically correct” |

*Hume's law, that is, an “ought” cannot be derived from an “is” (Segal and Tauber).22

Table 4.

Theme—Core Concepts

| Categories | Core Concepts of mental health |

|---|---|

| Agency/autonomy/control | “The core concepts of mental health that I find useful are very similar to Amartya Sen's conception of “capabilities”—the things a person is able and substantively free to do in pursuit of a life that the person has reason to value” (ie, Direction C) |

| “I would say that the positive subjective evaluation of one's own mental health focuses on the feeling or belief that one can cope with one's life circumstances…I hesitate to include a broader range of negative outcomes since they would be determined by one's circumstances (e.g., the amount of control one has in one's life)…sphere or community (with the distinction between the two being important primarily to allow for the option of an isolated existence by choice versus social exclusion)” (ie, Direction D) | |

| Coping with stressors/adapting to change | “The ability to navigate and adapt to one's environment seems key…” |

| “Ability to adapt psychologically to adverse circumstances…a sense of social/emotional wellness or maturity in the face of life's vicissitudes (not necessarily happiness, but dealing with life's ups and downs in a relatively effective and steady way)” | |

| Balance/stability | “Well-being, with a particular emphasis on resources for living with lucid thinking and emotional depth and stability” (ie, Direction D) |

| Meaningful relationships and participation | “Sense of being part of a vibrant society, with agency to make change for your and others, and supportive relationships and governance” (ie, Direction E) |

| “The objective evaluation focuses on one's ability to participate meaningfully in one's life sphere or community (with the distinction between the two being important primarily to allow for the option of an isolated existence by choice versus social exclusion). However, meaningful participation is typically defined by local social norms” (ie, Directions D and E) | |

| “Being able to offer some sort of product to the society (where you can get your essentials to live), to have empathy for another human being and capable of having an intimate and sustainable affectionate relationship” (ie, Direction E) | |

| Dignity | “A state of mind that allows one to lead one's life knowing that one's dignity and integrity as a human being is respected by others, that in the journey of life one's diversity of experiences thereof will be embraced” (ie, Direction D) |

| Enjoying life/satisfaction/pleasure | “Mental health is expressed by the ability to enjoy life and love…” |

| Hope/optimism for Future | “Mental Health is living a hopeful, fulfilling, self-determining life…” (ie, Direction C) |

| Insight/mindfulness/rational thought | “Logic and analyzing of scenarios, reflective & reflexive thinking” |

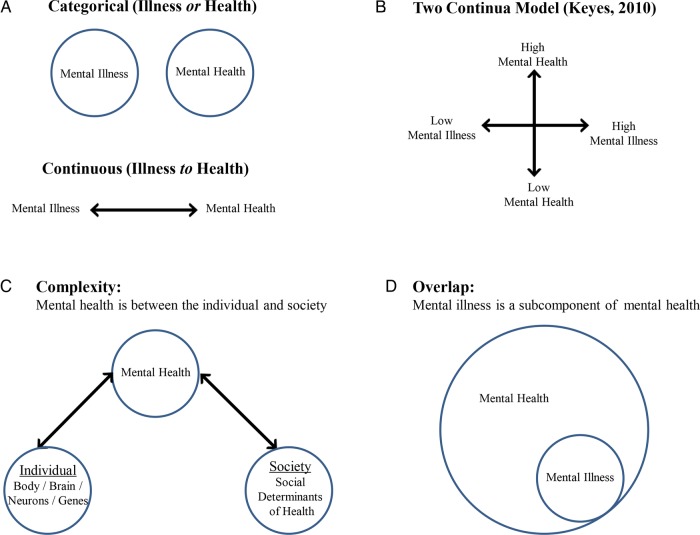

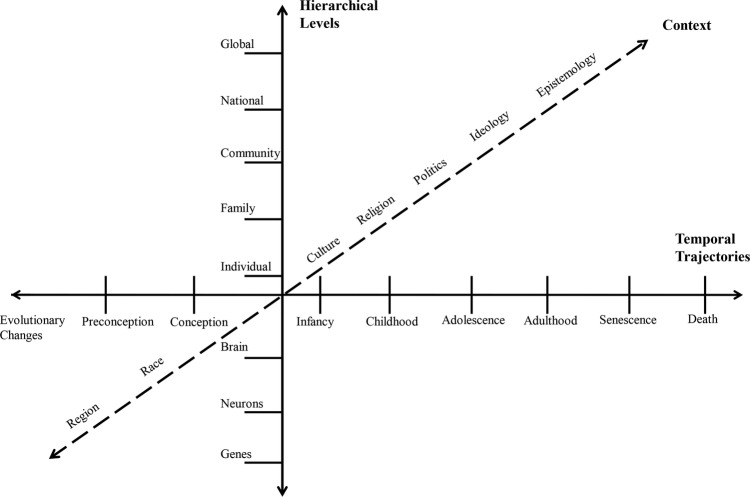

The theme of Positionality demonstrated how respondents positioned their conceptualisations of mental health within an explicit or implicit framework of understanding (table 3, figures 2 and 3). Several respondents described the core concepts in terms of binary or conflicting dynamics or as categorical or continuous. Some respondents pointed to the mutual exclusivity of ‘mental health’ and ‘mental illness’ while others described these concepts as distinct points separated on a continuum or as overlapping. Respondents specified the complexity of mental health, for example, positioning mental health explicitly outside of, and specifically in between, the individual and society. Several respondents framed the core concepts of mental health as descriptive versus prescriptive, arguing that these must be empirically determined and defined (ie, describing what is) rather than prescribed according to values and morals (ie, describing what should be). In accordance with Hume's Law (ie, an ‘ought’ cannot be derived from an ‘is’),22 several respondents cautioned that problems of living, such as ‘poverty, vices, social injustices and stupidity’, should not be defined ‘as medical problems’. Many respondents described mental health in relation to hierarchical levels, and/or temporal trajectories, and/or context (table 3, figure 3). Respondents articulated the multiple levels at which mental health can be understood (ie, from the basic unit of the gene, through the individual and up to the globe) and how meaning changes across time (ie, mental health described as functioning in line with our evolutionary ancestors, to current developmental mechanisms and including expectations of a peaceful death and spiritual existence) and across context (ie, from region, to race, to culture, to epistemology). In the second round of data analysis, we searched for bias in participants’ reporting of evidence-based models and bias against other sources of information; there was support for objective and subjective sources in conceptualising mental health.

Figure 2.

Positionality. The overarching perspective or point-of-reference used to describe the constructs of mental health and illness.

Figure 3.

Complexity. Descriptions of mental health in relation to hierarchical levels, and/or spatial directions, and/or temporal trajectories.

A second theme of Paradigms/Theories/Models developed as respondents discussed the need to perceive health through various frameworks (eg, recovery, resilience, human flourishing, quality of life, developmental and evolutionary theories, cultural psychiatry and ecology). Some respondents noted that current definitions of mental health treat problems of living as medical problems, rather than adaptive responses to the conditions that people experience, and that alternative explanations should be considered: “An evolutionary approach to these conditions suggests that anxiety and depression (as responses to social stressors) evolved to help the individual take corrective action that could ameliorate the negative effects of these stressors”. Some respondents emphasised that ‘low’ mental health did not equate to mental illness, but rather a state of hopelessness and lack of personal autonomy, whereas ‘high’ mental health was demonstrated by ‘meaningful participation, community citizenship, and life satisfaction’. Others referenced Westerhof and Keyes's23 two-continuum model describing mental illness and mental health as related by two distinct dimensions.

The Core Concepts of mental health (figure 1, table 4) largely described factors relating to the individual—as opposed to society—that are observed in correlation with mental health and which are necessary, to some degree or another, but not normally sufficient on their own to achieve mental health. Concepts related to agency, autonomy and control appeared frequently in relation to an individual's ability or capacity to effectively deal with and/or create change in his or her environment (Directions D–E). Agency/autonomy/control reappeared as an essential component of other core concepts: agency may be required in order to engage in meaningful participation (eg, ‘sense of being part of a vibrant society, with agency to make change for you and others, and supportive relationships and governance’) and in dignity (eg, ‘a state of mind that allows one to lead one's life knowing that one’s dignity and integrity as a human being is respected by others’). A cluster of concepts describing the self signified (1) the subjective experience of the individual as fundamental to well-being and (2) the importance of one's ability, confidence and desire to live in accordance with one's own values and beliefs in moving towards the fulfilment of one's goals and ambitions (figure 1).

Social and Environmental Factors reflected the societal factors external to the individual that affect mental health. Although many respondents listed the basic necessities for general health/mental health (eg, housing, food security, access to health services, equitable access to public resources, childcare, education, transportation, support for families, respect for diversity, opportunities for building resilience, self-esteem, personal and social efficacy, growth, meaning and purpose, and sense of safety and belonging, and employment), some also recommended approaches to achieving social equity (eg, “mental health needs to be protected by applying antiracism, antioppression, antidiscrimination lens to prevention and treatment”) (figure 1, Direction D). A distinct category of human rights developed from responses to the third open-ended question (eg, “What is missing?”) (figure 1). Several respondents suggested that a basic standard, analogous to a legal definition, is required (table 3) and/or that “a human rights, political, economic and ecosystem perspective” should be included.

Discussion

The international exploratory ‘What is Mental Health?’ survey sought the opinions of individuals, across multiple modes of inquiry, on what they perceived to be the core concepts of mental health. The survey found dissatisfaction with current definitions of mental health. There was no consensus among this group on a common definition. However, there was significant agreement among subcomponents of the definitions, specifically factors beyond the ‘ability to adapt and self-manage’, such as ‘diversity and community identity’ and creating distinct definitions, “one for individual and a parallel for community and society.” The Core Concepts of mental health that participants identified were predominantly centred on factors relating to the individual, and one's capacity and ability for choice in interacting with society. The concepts of agency, autonomy and control were commonly mentioned throughout the responses, specifically in regard to the individual's ability or capacity to effectively deal with and/or create change in his or her environment. Similarly, respondents pointed to the self as an essential component of mental health, signifying the subjective experience of the individual as fundamental to well-being, particularly in relationship to achieving one's valued goals. Respondents suggested that mentally healthy individuals are socially connected through meaningful participation in valued roles (ie, in family, work, worship, etc), but that mental health may involve being able to disconnect by choice, as opposed to being excluded (eg, having the capacity and ability to reject social, legal and theological practices). In contrast, Social and Environmental Factors reflected respondents’ emphasis on factors that are external to the individual and which can influence the core concepts of mental health. Many respondents reiterated the basic necessities for general health/mental health, similar to the foundations of Maslow's hierarchy of needs,24 and their recommendations for achieving social equity.

Descriptions of the core concepts of mental health were highly influenced by respondents’ Positionality and Paradigms/Theories/Models of reference, which often propelled the discourse of “What is mental health?” in opposing directions. The debate as to whether mental health and illness are distinct constructs, or points of reference on a continuum of being, was a common theme. Respondents were either, adamant in asserting the distinction between the descriptive or prescriptive nature of the core concepts, or, ardent in integrating them, producing ideas such as describing mental health as a life free of poverty, discrimination, oppression, human rights violations and war. Respondents’ made repeated references to human rights, suggesting that a basic standard, analogous to a legal definition, is required, and that ‘a human rights, political, economic and ecosystem perspective’ should be included. Again, in the tradition of Hume's ‘ought–is’ distinction, several respondents cautioned that problems of living, such as ‘poverty, vices and social injustices…’ should not be defined ‘as medical problems’. The significance of this issue cannot be understated: while we asked respondents what the core concepts of mental health are, overwhelmingly they answered in terms of what they should be. This finding is similar to other issues in public health policy that address instances of ‘conflating scientific evidence with moral argument’.15 22 Indeed, a primary criticism of the WHO definition of health is that its declaration of “complete physical, mental, and social wellbeing”6 is prescriptive rather than descriptive.15 Such a definition “contributes to the medicalization of society” and excludes most people, most of the time, and has little practical value “because ‘complete’ is neither operational nor measurable.”15

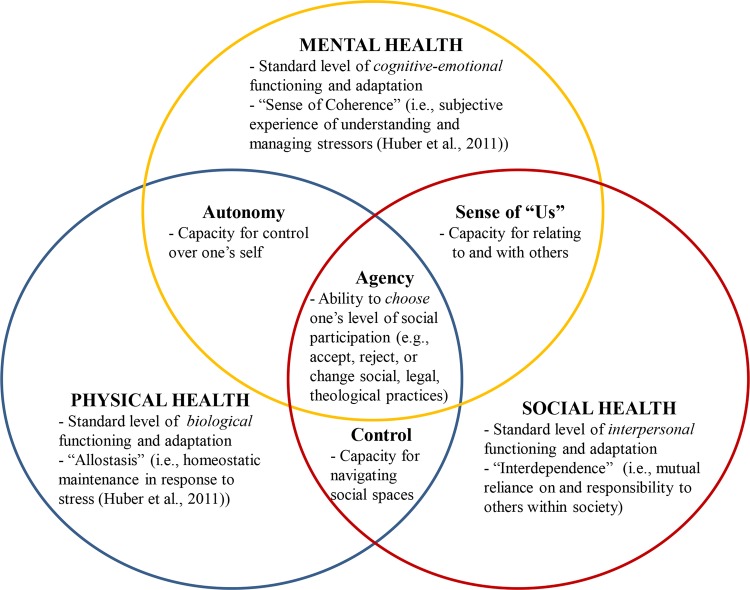

Accordingly, we propose a transdomain model of health (figure 4) to inform the development of a comprehensive definition for all aspects of health. This model builds on the three domains of health as described by WHO6 12 and Huber et al,15 and expands these definitions to include four specific overlapping areas and the empirical, moral and legal considerations discussed in the current study. First, all three domains of health should have a basic legal standard of functioning and adaptation. Our findings suggest that for physical health, a standard level of biological functioning and adaptation would include allostasis (ie, homeostatic maintenance in response to stress), whereas for mental health, a standard level of cognitive–emotional functioning and adaptation would include sense of coherence (ie, subjective experience of understanding and managing stressors), similar to Huber et al's15 proposal. However, for social health, a standard level of interpersonal functioning and adaptation would include interdependence (ie, mutual reliance on, and responsibility to, others within society), rather than Huber et al's15 focus on social participation (ie, balancing social and environmental challenges). Our results provide further insight into how these domains interact to affect overall quality of life. Integration of mental and physical health can be defined by level of autonomy (ie, the capacity for control over one's self), whereas integration of mental and social health can be defined by a sense of ‘us’ (ie, capacity for relating to others); the integration of mental and physical health can be defined by control (ie, capacity for navigating social spaces). The highest degree of integration would be defined by agency, the ability to choose one's level of social participation (eg, to accept, reject or change social, legal or theological practices). Such a transdomain model of health could be useful in developing cross-cultural definitions of physical, social and mental health that are both inclusive and empirically valid. For example, Valliant's25 seven models for conceptualizing mental health across cultures are all represented, to varying degrees, within the proposed transdomain model of health. The basic standard of functioning across domains which is proposed here is congruent with Valliant's25 criteria for mental health to be ‘conceptualised as above normal’ and defined in terms of ‘multiple human strengths rather than the absence of weaknesses’, including maturity, resilience, positive emotionality and subjective well-being. In addition, Valliant's25 conceptualisation of mental health as ‘high socio-emotional intelligence’ is also represented in the transdomain model's highest level of integration of the three areas for full individual autonomy. Finally, Valliant's25 cautions for defining positive mental health—being culturally sensitive, recognising that population averages do not equate to individual normalcy and that state and trait functioning may overlap, and contextualising mental health in terms of overall health—are all addressed within the transdomain model.

Figure 4.

Transdomain Model of Health. This model builds on the three domains of health as described by WHO6 12 and Huber et al15 and expands these definitions to include four specific overlapping areas and the empirical, moral, and legal considerations discussed in the current study. There are three domains of health (ie, physical, mental, and social), each of which would be defined in terms of a basic (human rights) standard of functioning and adaptation. There are four dynamic areas of integration or synergy between domains and examples of how the core concepts of mental health could be used to define them.

Strengths and limitations of the current study

We are unaware of any study to date that has asked this research question to a group of international experts in the broad field of mental health. Although our survey sample was small (N=50), it was diverse with regard to place of origin and expertise; it was also further validated by participants (N=58) at a day-long conference on mental health through discussion, debate and written responses. The current study included global experts who dedicate their research and professional lives to advancing the standards of mental health. Of particular note was that little to no consensus among the selected group of experts on any particular definition was found. In fact, this was simultaneously a limitation and strength of the study: the small sample size limited the scope of the core concepts of mental health, but indicated that it was sufficient to demonstrate that there are highly divergent definitions that are largely dependent on the respondents’ frame of reference. It is possible that saturation was not achieved in regards to the diversity of responses. Further, more than half of the survey respondents were from Canada, which may have influenced the preference towards the PHAC definition of mental health. Although there were advantages to using a snowball sampling method, another type of sampling method (eg, cluster sampling, stratified sampling) may have resulted in more varied responses to the survey items. The next logical step would be to survey experts in countries currently not represented and then ultimately survey members of the general public with regard to their conceptual and pragmatic understanding of mental health. One of the a priori objectives for the survey was to eventually create a consensus definition of mental health that could be used in public policy; this objective was not communicated in the survey, nor did we actually ask this question. Our results indicate that finding consensus on a definition of mental health will require much more convergence in the frame of reference and common language describing components of mental health. Even we, as authors, have been challenged by consensus. For example, some of us wish to emphasise that future work should focus on developing an operational definition that can be applied across disciplines and cultures. Others among us suggest further exploring what purpose a definition of mental health would or should serve, and why. In contrast, others among us wish to emphasise the process of conceptualising mental health versus the outcome or application of such a definition. What we hoped would be a straightforward, simple question, designed to create consensus for a definition of mental health, ultimately demonstrated the nuanced but crucial epistemological and empirical influences on the understanding of mental health. Based on the results of the survey and conference, we present a preliminary model for conceptualising mental health. Our study provides evidence that if we are to try to come to a common consensus on a definition of mental health, we will need to understand the frame of reference of those involved and try to parse out the paradigms, positionality and the social/environmental factors that are offered from the core concepts we make seek to describe. Future work may also need to distinguish between the scientific evidence of mental health and the arguments for mental health. Similar debates in bioethics22 26–28 demonstrate the theoretical and practical limitations of science for proscribing human behaviour, especially with regard to individual freedom and social justice.

Conclusions

Our results suggest that any practical use of a definition of health will depend on the epistemological and moral framework through which it was developed, and that the mental and social domains may be differentially influenced than the physical domain. A definition of health, grounded solely in biology, may be more applicable across diverse populations. A definition of health encompassing the mental and social domains may vary more in application, particularly across systems, cultures or clinical practices that differ in values (eg, spiritual, religious) and ways of understanding and being (eg, epistemology). A universal (global) definition based on the physical domain could be parsed out separately from several unique (local) definitions based on the mental and social domains. Understanding the history and evolution of the concept of mental health is essential to understanding the problems it was intended to solve, and what it may be used for in the future.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to extend their gratitude to their colleagues for their generous feedback, constructive critiques and recommendations for the project, and to the many volunteers who organised the conference. Special thanks to Nina Flora, Helen Thang, Andrew Tuck, Athena Madan, David Wiljer, Alex Jadad, Sean Kidd, Andrea Cortinois, Heather Bullock, Mehek Chaudhry and Anika Maraj.

Footnotes

Contributors: All the authors contributed to the conceptualisation of the project. LAM wrote the manuscript. SB, KR, ZD, CL and KM contributed to the content and editing of the manuscript. LAM, SB, KR, ZD, CL and EW created the survey and conducted data analyses. SB, KR and LAM presented findings at the conference. LAM, SB, KR, ZD and EW led the focused discussion groups. KM supervised the project. LM is the guarantor.

Funding: This work was performed with grants from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) for the Social Aetiology of Mental Illness Training Program at the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional are data available.

References

- 1.Whiteford HA, Degenhardt L, Rehn J et al. Global burden of disease attributable to mental and substance use disorders: findings from the global burden of disease study 2010. Lancet 2013;382:1575–86. 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61611-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Patel V, Belkin GS, Chockalingham A et al. Grand challenges; integrating mental health services into priority care platforms. PloS Med 2013;10:e1001448 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001448 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.WHO. 2008 Policies and practices for mental health in Europe—meeting the challenges. http://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0006/96450/E91732.pdf.

- 4.Carter JW, Hidreth HM, Knutson AL et al. Mental health and the American Psychological Association. Ad hoc Planning Group on the Role of the APA in Mental Health Programs and Research. Am Psychol 1959;14:820–5. 10.1037/h0043919 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cattan M, Tilford S. Mental health promotion: a lifespan approach. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill International; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 6.WHO. 1948 Constitution of the World Health Organization, 2006. http://www.who.int/governance/eb/who_constitution_en.pdf

- 7.WHO. Prevention of mental disorders. Geneva: 2004. http://www.who.int/mental_health/evidence/en/prevention_of_mental_disorders_sr.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alonso AM. What is mental health? Who are mentally healthy? Int J Soc Psychiatry 1960;6:302–5. doi:10.1177/002076406000600318 10.1177/002076406000600318 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sells SB. The definition and measurement of mental health. Washington DC: National Center for Health Statistics, U.S. Public Health Service, 1969. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sartorius N. Fighting for mental health. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bhugra D, Till A, Sartorius N. What is mental health? Int J Soc Psychiatry 2013;1:3–4. 10.1177/0020764012463315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.WHO. Mental health: strengthening mental health promotion, 2001; Fact Sheet No. 220 Geneva, Switzerland, 2001. Updated August 2014: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs220/en/ [Google Scholar]

- 13.Health Education Authority (HEA). Mental health promotion: a quality framework. London: HEA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mental Health Foundation (MHF). What works for you? London: MHF, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huber M, Knottnerus JA, Green L et al. How should we define health? BMJ 2011;343:d1463–6. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmj.d4163 10.1136/bmj.d4163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Popay J. WHO definition of health does remain fit for purpose. Response to Huber et al. (2011). How should we define health? BMJ 2011;343:d1463–6. http://www.bmj.com/rapid-response/2011/11/03/rewho-definition-health-does-remain-fit-purpose-2# [Google Scholar]

- 17.Macaulay AC. How should we define health? Response to Huber et al. (2011). How should we define health? BMJ 2011;343:d1463–6. http://www.bmj.com/rapid-response/2011/11/03/how-should-we-define-health [Google Scholar]

- 18.Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC). The human face of mental health and mental illness in Canada 2006. Ottawa, ON: Minister of Public Works and Government Services Canada, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Braun V, Clark V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol 2006;3:77–101. 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Patton MQ. Enhancing the quality and credibility of qualitative analysis. Health Serv Res 1999;34:1189–208. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stanfield RB. The art of focused conversations: 100 ways to access group wisdom in the workplace. BC, Canada: New Society Publishers, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Segal SP, Tauber AI. Revisiting Hume's Law. Am J Bioeth 2007;7:43–5. 10.1080/15265160701638694 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Westerhof GJ, Keyes CLM. Mental illness and mental health: the two continua model across the lifespan. J Adult Dev 2010;17:110–19. 10.1007/s10804-009-9082-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Maslow A. Towards a psychology of being. New York: Van Nostrand, 1968. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Valliant GE. Positive mental health: is there a cross-cultural definition? World Psychiatry 2012;11:93–9. 10.1016/j.wpsyc.2012.05.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tauber AI. Is biology a political science? BioScience 1999;49:479–86. 10.2307/1313555 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tauber AI. Patient autonomy and the ethics of responsibility. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zanni P, Stavis G. The effectiveness and ethical justification of psychiatric outpatient commitment. Am J Bioeth 2007;7:31–41. 10.1080/15265160701638678 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]