Abstract

Introduction

Non-specific chronic low back pain (NSCLBP) is a very common and costly musculoskeletal disorder associated with a complex interplay of biopsychosocial factors. Cognitive functional therapy (CFT) represents a novel, patient-centred intervention which directly challenges pain-related behaviours in a cognitively integrated, functionally specific and graduated manner. CFT aims to target all biopsychosocial factors that are deemed to be barriers to recovery for an individual patient with NSCLBP. A recent randomised controlled trial (RCT) demonstrated the superiority of individualised CFT for NSCLBP compared to manual therapy combined with exercise. However, several previous RCTs have suggested that class-based interventions are as effective as individualised interventions. Therefore, it is important to examine whether an individualised intervention, such as CFT, demonstrates clinical effectiveness compared to a relatively cheaper exercise and education class. The current study will compare the clinical effectiveness of individualised CFT with a combined exercise and pain education class in people with NSCLBP.

Methods and analysis

This study is a multicentre RCT. 214 participants, aged 18–75 years, with NSCLBP for at least 6 months will be randomised to one of two interventions across three sites. The experimental group will receive individualised CFT and the length of the intervention will be varied in a pragmatic manner based on the clinical progression of participants. The control group will attend six classes which will be provided over a period of 6–8 weeks. Participants will be assessed preintervention, postintervention and after 6 and12 months. The primary outcomes will be functional disability and pain intensity. Non-specific predictors, moderators and mediators of outcome will also be analysed.

Ethics and dissemination

Ethical approval has been obtained from the Mayo General Hospital Research Ethics Committee (MGH-14-UL). Outcomes will be disseminated through publication according to the SPIRIT statement and will be presented at scientific conferences.

Trial registration number

(ClinicalTrials.gov NCT02145728).

Keywords: PAIN MANAGEMENT, PUBLIC HEALTH, PRIMARY CARE

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This will be the first randomised controlled trial to compare the clinical effectiveness of a novel individualised treatment called cognitive functional therapy with a combined exercise and pain education class in people with non-specific chronic low back pain (NSCLBP).

Methodological qualities of the trial include: three intervention sites, blinded assessment and concealed allocation, an active comparison group, long-term follow-up, appropriate sample size calculation, treatment fidelity measures and a planned intention-to-treat analysis.

Only patients with NSCLBP greater than 6 months will be included, and while inclusion and exclusion criteria are broad, the study results will not be generalisable to all people with low back pain.

Therapist and patient blinding is not possible.

Introduction

Non-specific chronic low back pain (NSCLBP) is a very common and costly musculoskeletal disorder, resulting in significant personal, social and economic burden.1–3 There is strong evidence that NSCLBP is associated with a complex interaction of factors. These include physical factors (eg, maladaptive postures and movement patterns, altered body perception, pain behaviours and deconditioning),4–8 cognitive factors (eg, unhelpful beliefs, catastrophising, hypervigilance, maladaptive coping strategies, poor self-efficacy),9–14 psychological factors (eg, fear, anxiety, depression),15–18 lifestyle factors (eg, physical inactivity, sleep problems, chronic life stress),19–22 neurophysiological factors (eg, peripheral and central nervous system sensitisation),23–27 and social factors (eg, socioeconomic status, family, work and culture).28 29 Despite this complex interaction of factors in NSCLBP, with many of these factors being potentially modifiable, most current interventions neither target multiple aspects of an individual's pain experience nor individualise the targeting of such factors for each patient.30 31 Therefore, it is not surprising that treatments such as manual therapy, exercise, medications, relaxation, cognitive behavioural therapy and acceptance and commitment therapy, while reducing disability and enhancing quality of life to an extent, are not superior to each other and have a limited impact on pain in the long term.32–38

Cognitive functional therapy (CFT) is a novel, patient-centred behavioural intervention which addresses multiple aspects in NSCLBP. This approach focuses on changing patient beliefs, confronting their fears, educating them about pain mechanisms, enhancing mindfulness of the control of their body during pain provocative functional tasks, training them to reduce excessive trunk muscle activity and change behaviours related to pain provocative movements and postures.31 In a recent randomised controlled trial (RCT) among people with moderate NSCLBP, this approach was significantly more effective than combining manual therapy and exercise.39 Similar results were demonstrated for a high-risk group of patients with NSCLBP treated with CFT in a recent single-centre cohort study in Ireland.40 However, a range of RCTs have suggested that class-based treatments are as effective as individualised treatment in musculoskeletal pain populations,41–52 including NSCLBP. In addition, many people with chronic musculoskeletal pain, including NSCLBP, appear to be either over-treated or treated inefficiently, without this additional one to one intervention necessarily improving their outcome.53–57 Therefore, it is important to examine whether an individualised intervention, such as CFT, is demonstrative of clinical-effectiveness as compared to a relatively cheap comparison treatment such as a combined exercise and pain education class.

Objectives

Primary objective

The primary objective is to examine the clinical effectiveness of CFT, based on whether participants in the CFT arm report significant improvements in the short, medium and long term on measures of functional disability and pain intensity, relative to those allocated to combined exercise and pain education classes.

Secondary objectives

The secondary objectives include examining whether CFT has a significant effect on costs relative to classes in the short, medium and long term, and examining mediators (back pain beliefs, fear, coping, self-efficacy, sleep, depression, anxiety, stress and treatment satisfaction) as well as moderators and predictors (demographic information (age, sex, duration of CLBP), socioeconomic status, baseline risk of chronicity, number of pain areas and general health symptoms) of treatment effect across both interventions.

Methods and analysis

Design and setting

The design is a three site RCT comparing individualised CFT and a class-based intervention. The sites are two primary care centres (Ballina Primary Care Centre and Claremorris Primary Care Centre) and one public hospital (Mayo General Hospital) that receives referrals from both medical consultants in secondary care and primary care general practitioners (GPs) in Ireland. Any modifications to the protocol which may impact on the conduct of the study will require a formal amendment to the protocol. Such amendment will be agreed on by the project management committee (MOK, KOS, NK, POS, HP and NB) and approved by the relevant ethics committee prior to the implementation of the modifications. Minor administrative changes to the protocol will be agreed on by the project management committee and will be documented in a memorandum.

Ethical considerations

Ethical approval has been granted by the relevant hospital research ethics committee (MGH-14-UL). Written informed consent will be obtained from all participants included in the study. Participants will be informed that they are not obliged to take part in the study and are free to withdraw at any time, without any negative consequences on their future care. All efforts will be made to protect the privacy of the participants, and to keep their names and personal information confidential at all times. This will be achieved by referring to all participant records and information only by their assigned research code. No significant adverse reactions are anticipated in the study, but these will be monitored. Both interventions will involve some exercise. This involves a very small risk of increased stiffness and soreness initially. However, all exercise will be performed at a speed and intensity under the participant’s own control. The suitability of exercise for the participants will be assessed at entry to the study by the treating physiotherapist.

Recruitment and participants

Participants who are referred to the physiotherapy service in each site will be screened individually for 15–20 min. Participants meeting the eligibility criteria will be recruited. All participants will be given the option of receiving usual care physiotherapy (individualised) or taking part in the study. Those interested in participating will be presented with written information about the study, including its aims and procedures (see online supplementary file 1). Here it is clearly stated that there are two active intervention arms and that based on current knowledge, it is not known which intervention is superior. The patients will provide written informed consent prior to randomisation (see online supplementary file 2). The inclusion/exclusion criteria are described in table 1.

Table 1.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria for study participation

| Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

|---|---|

| ▸ Aged between 18 and 75 ▸ Chronic low back pain for at least 6 months duration ▸ Score of 14% or more for disability on the Oswestry Disability Index (ODI) ▸ Independently mobile (with or without aids), to be capable of participating in a rehabilitation programme ▸ Be able to speak and understand English well enough to be able to complete the questionnaires independently |

▸ Primary pain area is not the lumbar spine (from T12 to buttocks) ▸ Leg pain as the primary problem (eg, nerve root compression or disc prolapse with true radicular pain/radiculopathy, lateral recess or central spinal stenosis) ▸ Less than 6 months after lumbar spine, lower limb or abdominal surgery ▸ Pain relieving procedures such as injection-based therapy (eg, epidurals) and day case procedures (eg, rhizotomy) in the past 3 months ▸ Pregnancy ▸ Rheumatological/inflammatory disease (eg, rheumatoid arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, psoriatic arthritis, lupus erythematosus, Scheuermann's disease) ▸ Progressive neurological disease (eg, multiple sclerosis, Parkinson’s disease, motor neuron disease) ▸ Scoliosis (if considered the primary driver of pain) ▸ Unstable cardiac conditions ▸ Red flag disorders like malignancy/cancer, acute traumas like fracture (less than 6 months ago) or infection, spinal cord compression/cauda equina |

Treatment allocation and randomisation

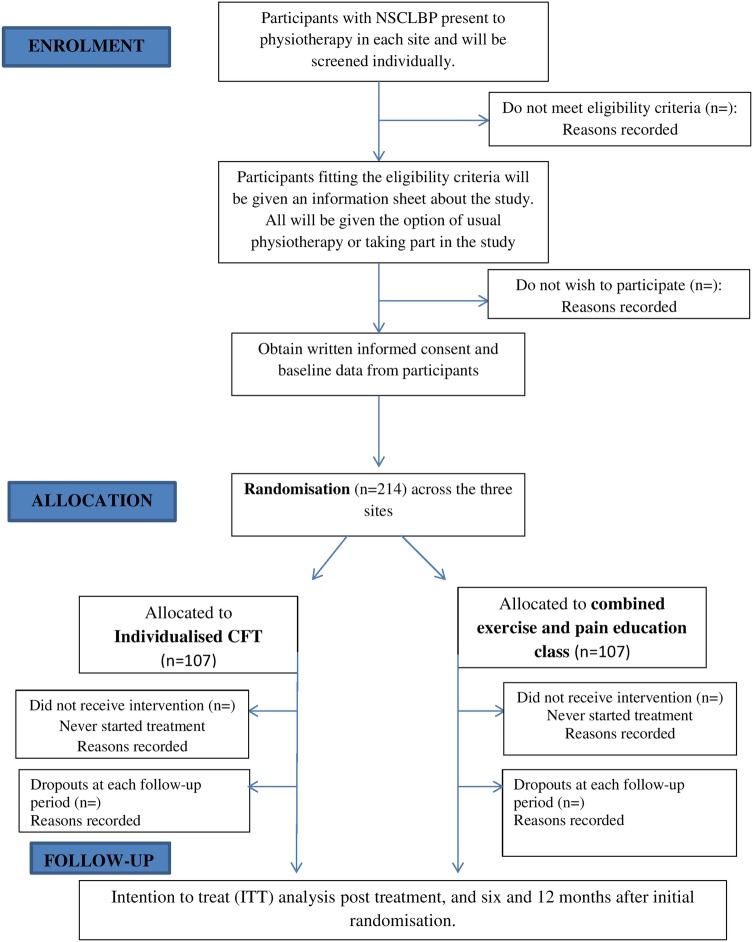

To ensure concealment of allocation, patients will only be randomised to receive the individualised CFT or the class-based intervention after it is clear that they meet the inclusion criteria. Allocation will be picked from an opaque envelope. The envelope will contain only two pieces of paper. Participants will be asked to pick one piece of paper from the envelope. One piece of paper will have the letter ‘C’ for class and the other, letter ‘I’ for individual CFT. The number of participants who choose to withdraw from the study at this, or any other, stage will be recorded. Participant progress through the study is shown in figure 1.

Figure 1.

Trial design.

Baseline assessments

At the initial screening assessment when patients are screened for eligibility, all will have to complete the ODI58 to ensure they meet the criteria for inclusion. If eligible, and participants consent to participate after random allocation, they then complete the remaining sections of the questionnaire (see below) before their first intervention session which is within 2 weeks of the date of screening. In the event that their appointment is longer than 2 weeks after the initial screening session, they will recomplete all the questionnaires on the day of the first intervention session. The second of these baseline assessments will be used as baseline. In the event of an individual's ODI being less than 14%, they will remain in the study since they have already been randomised.

Interventions

All interventions will be provided by three physiotherapists (AT, LD and LA), with one physiotherapist working in each location. The treating physiotherapists have been trained to deliver the interventions to enhance standardisation of interventions. Training involved a blended learning approach, including interactive lectures and seminars, as well as clinical workshops where the management of NSCLBP as a multidimensional biopsychosocial disorder was discussed. Both interventions use a biopsychosocial approach.

The specific training for the CFT intervention involved the treating physiotherapists (1) observing CFT-trained tutors (http://www.pain-ed.com) assess and treat real patients with NSCLBP using CFT, and (2) assessing and treating patients with NSCLBP in front of the same CFT tutors. The specific training for the class-based intervention involved the development of a series of six classes, each including exercise and education. Discussions between the three treating physiotherapists and two of the study authors (KOS and MOK) will take place to ensure effective and consistent delivery across sites.

For both intervention arms, treating physiotherapists piloted the interventions until they were deemed competent to deliver the interventions. Treating physiotherapists were also provided with additional resources to support both the interventions, including written and web-based resources (eg, http://www.pain-ed.com) regarding the biopsychosocial nature of pain, the limited role of imaging in NSCLBP, and the role of behavioural changes such as activity, stress management and sleep hygiene in managing NSCLBP.

Experimental intervention: individualised CFT

The CFT intervention will be one to one, will involve hearing the full patient story regarding their pain, and the intervention will be targeted to meet the participants’ individual needs. All participants randomised to this group will undergo a comprehensive one-to-one interview and physical examination by the treating physiotherapist. This detailed examination will be essential in order to broadly identify the modifiable multidimensional drivers of pain and disability (pain provocative cognitive, movement and lifestyle behaviours) for each participant.39 40 59

During the interview, participants will be asked to provide information about their history of pain, pain area and nature, pain behaviour (aggravating/easing movements and activities), their primary functional impairments, disability, activity levels, lifestyle behaviours and sleep patterns. Participants will be also be questioned about their level of fear of pain and any avoidance of activities, work and social engagement. Their degree of pain focus, pain coping strategies, stress response and its relationship to pain, and their pain beliefs will also be established as will be any history of anxiety and depression. Finally, their beliefs and goals regarding management of their disorder will be ascertained.39 40 59

The physical examination will involve analysis of the participants’ primary functional impairments (eg, pain provocative, feared and/or avoided movements and functional tasks as reported during the interview), in order to identify maladaptive behaviours which include muscle guarding, ‘abnormal’ movements and postures, avoidant patterns and pain behaviours. They will also be assessed regarding their level of body control and awareness (body perception), as well as their ability to relax their trunk muscles and normalise pain provocative postural and movement behaviours, and the effect this has on their pain.39 40 59

Treatment will be provided in the local physiotherapy department at each site. The initial session will last approximately 1 h and follow-up sessions will range from 30 min to 1 h. Treatment frequency will vary pragmatically with each patient, though it is expected that appointments will start weekly and reduce in frequency over time. Similarly, treatment duration will vary from approximately 4 to 16 sessions. While 16 is the anticipated upper limit of sessions, eight is the expected average. The duration, and number, of treatments will be recorded. Each patient will receive an individualised targeted intervention directed at changing their individual cognitive, movement and lifestyle behaviours considered to be provocative and maladaptive of their disorder.6 31 60 There will be four main components to the intervention. These will be:

A cognitive component will focus on the factors identified from the examination that are considered to contribute to their pain disorder. This will include discussing the multidimensional nature of persistent pain as it pertains to the individual—and how beliefs, emotions and behaviours (movement and lifestyle) can reinforce a vicious cycle of pain sensitisation and disability. The various factors of the vicious cycle will be outlined in a personalised diagram for each participant based on the findings from the examination. Where considered appropriate, patients will be advised to read resources and watch patient videos on http://www.pain-ed.com and will be given leaflets on sleep, relaxation and mindfulness, the role of spinal imaging, such as MRIs, and regarding exercise and physical activity if these are considered relevant to their pain presentation by the treating physiotherapist.

Specific functional training will be designed to normalise maladaptive and provocative postural and movement behaviours as directed by the patient's individual presentation. This will involve a behavioural modification approach to rehabilitation where patients will be taught strategies aimed to enhance their body awareness and control in order to relax, and modify postures and tasks they report as being pain provocative. Where considered appropriate, patients will be given audio resources (eg, mindfulness CDs) to facilitate this process.

Targeted functional integration into daily life activities which are avoided by, and/or provocative for, the patient. This will vary between individuals, but will be likely to include targeting activities such as rolling in bed, sitting, standing up from sitting, walking, bending and lifting.

Physical activity and lifestyle advice will include promotion of gradually increasing physical activity based on their preference and presentation, advice on sleep hygiene, stress management strategies and social re-engagement.39 40 59

A key component underlying each of these four stages which may facilitate patients achieving a positive outcome will be maximising the contextual or ‘non-specific’ aspects of treatment. This will include using motivational interviewing techniques,61 as well as establishing and demonstrating empathy with the patient to enhance patient–therapist rapport and interaction.62 All instructions for participants will be written, when deemed appropriate by the physiotherapist and/or requested by the participants.

Control intervention: combined exercise and pain education class

This class-based intervention will not involve individual assessment or consideration of the patient's story. All participants in this class will receive the same intervention and it will not be specifically targeted to their individual needs.

The class-based intervention will consist of six classes over 6–8 weeks, each lasting approximately 1 h and 15 min, with up to 10 participants in each class. It will have biopsychosocially orientated sessions involving education, exercise and relaxation/mindfulness. Everybody will have the opportunity to ask questions and answers will be provided for the whole class. It differs from the individualised CFT in that it is not targeted to the individual, it does not involve one-to-one attention, and everybody gets the same advice and functional activation exercises. Each class will start with a 30 min discussion, using a different focus/topic each week. The topics to be covered will include explaining contemporary understanding of pain and the role of the nervous system,63 the multidimensional nature of CLBP and common myths about CLBP, posture and ergonomics, exercise, relaxation and sleep. All talks will involve the use of visual aids (eg, slides, flipcharts) and a copy of the slides from every class will be provided to participants. The second part of the class will be a 40 min gradually progressive exercise circuit involving aerobic, flexibility and strengthening exercises, similar to the class-based intervention delivered in a previous RCT.64 The exercises will be step-ups, squats, sit to stands, marching/jogging on spot, wall push-ups, hip lift/bridging, knees to chest/lumbar flexion, rolling knee to side/lumbar rotation, the cat stretch and the hip flexor lunge stretch. Participants will be instructed to do the exercises at their own desired pace. No special equipment will be needed. All participants will be given a copy of these exercises to do at home and will be encouraged to do these once a day. Finally, a 5 min relaxation/mindfulness component will take place at the end of each class. In addition, all participants will be advised to watch patient videos and read resources on http://www.pain-ed.com, and will receive the aforementioned leaflets on sleep, relaxation and mindfulness, the role of spinal imaging, such as MRI, and on exercise and physical activity. Efforts will be made to enhance the ‘non-specific’ aspects of treatment by creating an open atmosphere, encouraging patient interaction, engagement and opportunity for questions and input.

Outcome measures

All outcome measures will be self-reported and will be conducted preintervention (see online supplementary file 3), postintervention (see online supplementary file 4) as well as 6 and 12 months (see online supplementary file 5) after randomisation. The primary outcome measures selected for this study are based on the Initiative on Methods, Measurement and Pain Assessment in Clinical Trials (IMMPACT) recommendations for outcome measures for chronic pain clinical trials. The rate of attrition among the participants during their completion of the intervention will be recorded.

Primary outcomes

The two primary outcomes of interest will be functional disability and pain intensity. Functional disability will be measured using the ODI, a validated 10-item questionnaire.58 Pain intensity will be assessed using the Numeric Rating Scale, a validated 0–10 scale.65 Participants will asked to rate their pain on average during the past week; 0 representing no pain and 10 representing pain as bad as you can imagine. Both will be assessed at all time-points (baseline, postintervention, as well as 6 and 12 months after randomisation).

Secondary outcomes

The secondary outcome of interest will be costs. Treatments and tests received, hospitalisations and tests, medications, equipment, aids and informal care, travel costs, employment status and work absenteeism will be assessed. The number and length of treatment sessions will also be documented by the treating physiotherapists. This will be assessed at 6 and 12 months (see online supplementary file 6).

Mediators of outcome

Beliefs: Beliefs about back pain will be assessed using the nine-item Back Beliefs Questionnaire.66

Fear: this will be measured using the four-item physical activity subscale of the Fear-Avoidance Beliefs Questionnaire.67

Coping: this will be measured using the five-item coping subscale of the Coping Strategies Questionnaire.68

Self-efficacy: this will be assessed using the 10-item Pain Self-Efficacy Questionnaire.69

Sleep, depression and anxiety: these will be assessed using the single item questions regarding these measures on the Subjective Health Complaints Inventory.70

Stress: this will be measured using the seven-item stress subscale of the Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale.71

Satisfaction: participant satisfaction with treatment will be assessed using a single item from the 18-item Patient Satisfaction Questionnaire. “The care that I have been receiving here is just about perfect”. 1=Strongly Agree, 2=Agree, 3=Unsure, 4=Disagree, 5=Strongly Disagree.72

Satisfaction will be assessed at postintervention only while the remaining mediators will be assessed at all time-points (baseline, postintervention, 6 and 12 months follow-up).

Non-specific predictors and moderators of outcome

Demographic information: Participants’ age, sex, duration of NSCLBP will be obtained.

Socioeconomic status: this will be assessed using the Socioeconomic Index.73 This questionnaire provides information about education, employment status, income, ability to pay bills, self-perceived health and satisfaction with number of friends. While aspects of some of these (eg, education) are unlikely to change, some (eg, work status, self-perceived health) may actually be targets of treatment.

Risk of chronicity: this will be measured using the 10-item short-form Orebro musculoskeletal screening questionnaire.74

Number of pain areas: this will be assessed using the Nordic Musculoskeletal Screening Questionnaire.75

General Health: general health symptoms will be assessed using the 13-item version of the Subjective Health Complaints Inventory70 and scored as simply the presence or absence of the 13 items.

Demographic information will be obtained at baseline only, while the remaining predictors and moderators will be assessed at all the time points.

Timing of outcome measurement

The aforementioned patient self-report outcomes will be collected at baseline (except satisfaction and costs) and immediately after the intervention by the treating physiotherapist. Costs will only be assessed 6 and 12 months after randomisation. Participants will then be sent copies of the same questionnaires by a blinded assessor (MOK) 6 and 12 months after their randomisation. If a participant does not respond to follow-up, they will be telephoned on up to two occasions each time to ask if they wish to complete the questionnaires.

Blinding

Questionnaires at all time points will be self-completed by the patient. Single blinding will be achieved by having an independent blinded assessor perform the follow-up assessments after 6 and 12 months. Questionnaires will be posted back to the blinded assessor. The blinded assessor will not be treating any of the participants, nor be aware of their group allocation. The statistician conducting the primary data analysis will also be blinded to group allocation. Blinding of the treating physiotherapists and participants will not be possible because they will know the intervention arm to which they have been allocated.

Data and treatment fidelity

A fidelity evaluation where the treating physiotherapists are observed while assessing and treating actual patients from the RCT will be conducted. For every participant in the study, the type and number of treatments received will be recorded. In addition, there will be session-by-session documentation of treatment content for the CFT arm by the treating physiotherapist. Standardised and regular training as well as monitoring and feedback will be given to the physiotherapists to facilitate successful delivery of both treatments. Physiotherapists will complete a series of standardised questionnaires (see online supplementary file 7) assessing their beliefs and attitudes towards CLBP and pain presentations (Health Care Professionals Pain and Impairment Relationship Scale,76 The Pain Attitudes and Beliefs Scale For Physiotherapists,77 The Practitioner Confidence Scale,78 The Attitudes to Back Pain Scale in Musculoskeletal Practitioners,79 and The Neurophysiology of Pain Questionnaire).80 The physiotherapists will also be asked to complete a clinical vignette81 and to provide demographic details, information about their physiotherapy training and general health. To assess quality of communication and interaction, some sessions from both intervention arms will be observed and audio recorded. These recorded sessions will also involve the physiotherapist, patient(s) and an observer completing the Working Alliance Theory of Change Inventory;82 physiotherapists will complete the Communication Assessment Tool.83 Qualitative interviews will be carried out with 8–15 participants from each treatment arm, depending on data saturation. Stratified sampling for these patient interviews will take place and be based on reaching the minimal clinically important difference (MCID) of ODI (30%)84 at 6-month follow-up. Participants will then be randomly selected and interviews will be conducted 6 to 12 months following randomisation to get their views on the care they received.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics will be used to summarise participant characteristics in the individualised CFT and class-based intervention. An intention to treat analysis using linear mixed models will be used to compare pain intensity and functional disability between the intervention arms and account for the correlation within-subject over time, while adjusting for differences in participant characteristics at baseline where appropriate. Sensitivity analyses and per protocol analysis will be used to explore whether adherence to the intervention influences the effect of the intervention on the primary outcomes. The analysis of the secondary outcomes will involve linear and non-linear mixed models for continuous and categorical responses where appropriate. Variable selection techniques will be used to identify the most parsimonious set of participant characteristics for inclusion as explanatory variables in each model. An analysis of the potential mediating effects of the secondary outcomes on treatment will be undertaken using the approach of Baron and Kenny.85 In addition, baseline variables will be assessed as non-specific predictors or moderators of treatment by including main and interaction terms in the models. The 5% level of statistical significance will be used throughout the analyses. In addition, the level of clinical significance will be also be reported by comparing any changes in outcome measures to the recognised MCID values84 for standardised outcome measures. A responder to treatment is defined as a >30% improvement on the ODI.84 All data will be analysed using the IBM SPSS Statistics V. 21 (Armonk, New York, USA) and R 3.1.1.86 Data will be inputted by one researcher (MOK) and a second researcher will randomly double-check 10% of the inputted data to ensure accuracy.

A thematic analysis approach will be used to analyse the qualitative interviews. When all the audio recordings have been transcribed verbatim, the transcripts will be imported into NVIVO 10. The analytic process will be adapted from Sandelowski and Barroso.87 It will involve the following three stages: (1) Extraction of findings and coding of findings for each interview, (2) Grouping of findings (codes) according to their topical similarity and (3) Abstraction of findings—analysing the grouped findings to identify additional patterns, overlaps, comparisons and redundancies to form a set of concise statements, which capture the content of all findings.

Analysis of costs to the participant after intervention

The cost analysis of participants after intervention will be undertaken at the follow-up times, 6 and 12 months after initial randomisation. The aims of the analysis will be to identify, measure and compare individual costs incurred by the participants in both groups. Concomitant care, interventions and tests received, hospitalisations and tests, medications, equipment, aids and informal care, travel costs, employment status and work absenteeism will be assessed by a postal questionnaire at these follow-up times and statistical analyses will compare differences between the treatment groups.

Sample size estimation

Based on the previous RCT using CFT,39 a sample size calculation estimates that a sample size of 64 in each group will have 80% power to detect a difference in means of 5.0 (disability) and 1.0 (pain) between the two arms of the study, assuming that the common SD is 10.0 (disability) and 2.0 (pain), and using a two-sided 5% significance test. Pilot data collection suggests a slightly larger drop-out rate from the class-based intervention. Consequently, allowing for a 40% dropout rate requires a sample size in each arm of 107, or an overall sample size of 214.

Data and safety monitoring

The Clinical Therapies Department at the University of Limerick, Ireland, will serve as the data coordinating centre responsible for data collection forms, coordination of data transfer and data analysis. Health of participants will be monitored through attending their interventions in the three sites. If any adverse events do take place, and in the unlikely event that harm is suffered, the project management team will liaise with local health service providers. All adverse events will be documented in the final written report of this study. All study data will be stored securely in the University of Limerick. All paper-based documents and data will be stored in a secure filing cabinet. All electronic data will be secured on a password-protected laptop. All documents that contain names or personal identifying information will be stored separately from other study data and identified by code number. Access to files will be limited to research staff involved in the study. The statistician for the final analysis will receive depersonalised data where the participants’ identifying information will be replaced by an unrelated sequence of numbers. There are no current plans for granting public access to the full protocol, participant-level data set or statistical code. However, if researchers wish to access the data set (eg, for conduct of secondary analysis or meta-analysis) the project management committee will try to facilitate this.

Dissemination

Results will be presented at international scientific conferences and in peer-reviewed publications. An open-access version of the study results will be made available through the University of Limerick's institutional repository. Trial participants will also be offered an opportunity to obtain the anonymised, overall study results.

Conclusion

This will be the first RCT to compare the clinical effectiveness of individualised CFT and a combined exercise and education class for people with NSCLBP. The study results will provide valuable information about the role of these interventions and has the potential to inform the clinical management of NSCLBP. A 36-month follow-up will be conducted if the 12-month follow-up results suggest this would be useful and if funding is available.

Footnotes

Contributors: MO and KO have been primarily responsible for study conception, design, analysis plan, funding acquisition and implementation. NK, WD and PO contributed to the conceptualisation and design of the study and implementation. MO drafted the background, methods and Discussion sections of the manuscript and coordinated manuscript preparation and revision. KO, PO and WD trained the treating physiotherapists. MO and KO developed the paper-based resources to be used for both interventions. PO, KO and WD have developed the http://www.pain-ed.com online platform which will be available to support both physiotherapists and patients during the study. AT, LA and LD contributed to the design of the interventions, data collection process and will perform the treatment interventions in the study. HP and NB performed the power size calculation, produced the statistical analysis plan and will perform the final study analysis. All authors provided critical evaluation and revision of the manuscript and have given final approval of the manuscript accepting responsibility for all aspects.

Funding: This work is sponsored by the Irish Research Council (IRC).

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: Ethical approval has been granted by the Mayo General Hospital Research Ethics Committee.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Hoy D, Bain C, Williams G. A systematic review of the global prevalence of low back pain. Arthritis Rheum 2012;64:2028–37. 10.1002/art.34347 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ma VY, Chan L, Carruthers KJ. Incidence, prevalence, costs, and impact on disability of common conditions requiring rehabilitation in the United States: stroke, spinal cord injury, traumatic brain injury, multiple sclerosis, osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, limb loss, and back pain. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2014;95:986–95. 10.1016/j.apmr.2013.10.032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vos T, Flaxman AD, Naghavi M et al. Years lived with disability (YLDs) for 1160 sequelae of 289 diseases and injuries 1990–2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet 2013;380:2163–96. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61729-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bray H, Moseley GL. Disrupted working body schema of the trunk in people with back pain. Br J Sports Med 2011;45:168–73. 10.1136/bjsm.2009.061978 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dankaerts W, O'Sullivan P, Burnett A et al. Differences in sitting postures are associated with nonspecific chronic low back pain disorders when patients are subclassified. Spine J 2006;31:698–704. 10.1097/01.brs.0000202532.76925.d2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dankaerts W, O'Sullivan P, Burnett A et al. Discriminating healthy controls and two clinical subgroups of nonspecific chronic low back pain patients using trunk muscle activation and lumbosacral kinematics of postures and movements: a statistical classification model. Spine J 2009;34:1610–18. 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181aa6175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.MacDonald D, Moseley GL, Hodges PW. Why do some patients keep hurting their back? Evidence of ongoing back muscle dysfunction during remission from recurrent back pain. Pain 2009;142:183–8. 10.1016/j.pain.2008.12.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Martel M, Thibault P, Sullivan M. The persistence of pain behaviors in patients with chronic back pain is independent of pain and psychological factors. Pain 2010;151:330–6. 10.1016/j.pain.2010.07.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Campbell P, Bishop A, Dunn KM et al. Conceptual overlap of psychological constructs in low back pain. Pain 2013;154:1783–91. 10.1016/j.pain.2013.05.035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Darlow B, Fullen BM, Dean S et al. The association between health care professional attitudes and beliefs and the attitudes and beliefs, clinical management, and outcomes of patients with low back pain: a systematic review. Eur J Pain 2012;16:3–17. 10.1016/j.ejpain.2011.06.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Main CJ, Foster N, Buchbinder R. How important are back pain beliefs and expectations for satisfactory recovery from back pain? Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 2010;24:205–17. 10.1016/j.berh.2009.12.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wertli MM, Eugster R, Held U et al. Catastrophizing-a prognostic factor for outcome in patients with low back pain-a systematic review. Spine J 2014;14:2639–57. 10.1016/j.spinee.2014.03.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Woby SR, Urmston M, Watson PJ. Self-efficacy mediates the relation between pain-related fear and outcome in chronic low back pain patients. Eur J Pain 2007;11:711–18. 10.1016/j.ejpain.2006.10.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sullivan MJ, Thorn B, Haythornthwaite JA et al. Theoretical perspectives on the relation between catastrophizing and pain. Clin J Pain 2001;17:52–64. 10.1097/00002508-200103000-00008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bener A, Verjee M, Dafeeah EE et al. Psychological factors: anxiety, depression, and somatization symptoms in low back pain patients. J Pain Res 2013;6:95–101. 10.2147/JPR.S40740 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Edit V, Eva S, Maria K et al. Psychosocial, educational, and somatic factors in chronic nonspecific low back pain. Rheumatol Int 2013;33:587–92. 10.1007/s00296-012-2398-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wertli MM, Rasmussen-Barr E, Held U et al. Fear avoidance beliefs–a moderator of treatment efficacy in patients with low back pain: a systematic review. Spine J 2014;14:2658–78. 10.1016/j.spinee.2014.02.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zale EL, Lange KL, Fields SA et al. The relation between pain-related fear and disability: a meta-analysis. J Pain 2013;14:1019–30. 10.1016/j.jpain.2013.05.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Briggs AM, Jordan JE, O'Sullivan PB et al. Individuals with chronic low back pain have greater difficulty in engaging in positive lifestyle behaviours than those without back pain: an assessment of health literacy. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2011;12:161 10.1186/1471-2474-12-161 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bjorck-van Dijken C, Fjellman-Wiklund A, Hildingsson C. Low back pain, lifestyle factors and physical activity: a population based-study. J Rehabil Med 2008;40:864–9. 10.2340/16501977-0273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Griffin DW, Harmon D, Kennedy N. Do patients with chronic low back pain have an altered level and/or pattern of physical activity compared to healthy individuals? A systematic review of the literature. Physiotherapy 2012;98:13–23. 10.1016/j.physio.2011.04.350 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kelly GA, Blake C, Power CK et al. The association between chronic low back pain and sleep: a systematic review. Clin J Pain 2011;27:169–81. 10.1097/AJP.0b013e3181f3bdd5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Luomajoki H, Moseley GL. Tactile acuity and lumbopelvic motor control in patients with back pain and healthy controls. BJSM 2011;45:437–40. 10.1136/bjsm.2009.060731 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nijs J, Meeus M, Cagnie B et al. A modern neuroscience approach to chronic spinal pain: combining pain neuroscience education with cognition-targeted motor control training. Phys Ther 2014;94:730–8. 10.2522/ptj.20130258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.O'Sullivan P, Waller R, Wright A et al. Sensory characteristics of chronic non-specific low back pain: a subgroup investigation. Man Ther 2014;19:311–18. 10.1016/j.math.2014.03.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tsao H, Galea M, Hodges P. Reorganization of the motor cortex is associated with postural control deficits in recurrent low back pain. Brain 2008;131:2161–71. 10.1093/brain/awn154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wand BM, Parkitny L, O'Connell NE et al. Cortical changes in chronic low back pain: current state of the art and implications for clinical practice. Man Ther 2011;16:15–20. 10.1016/j.math.2010.06.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lallukka T, Viikari-Juntura E, Raitakari OT et al. Childhood and adult socio-economic position and social mobility as determinants of low back pain outcomes. Eur J Pain 2014;18:128–38. 10.1002/j.1532-2149.2013.00351.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mitchell T, O'Sullivan PB, Burnett A et al. Identification of modifiable personal factors that predict new-onset low back pain: a prospective study of female nursing students. Clin J Pain 2010;26:275–83. 10.1097/AJP.0b013e3181cd16e1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mafi JN, McCarthy EP, Davis RB et al. Worsening trends in the management and treatment of back pain. JAMA Intern Med 2013;173:1573–81. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.8992 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.O'Sullivan P. It's time for change with the management of non-specific chronic low back pain. BJSM 2012;46:224–7. 10.1136/bjsm.2010.081638 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chaparro LE, Furlan AD, Deshpande A et al. Opioids compared to placebo or other treatments for chronic low-back pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013;8:CD004959 10.1002/14651858.CD004959.pub4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Furlan AD, van Tulder MW, Cherkin D et al. Acupuncture and dry-needling for low back pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2005;(1):CD001351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hayden J, Van Tulder MW, Malmivaara A et al. Exercise therapy for treatment of non-specific low back pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2005;(3):CD000335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Henschke N, Ostelo R, van Tulder MW et al. Behavioural treatment for chronic low-back pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2010;(7):CD002014 10.1002/14651858.CD002014.pub3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Menke JM. Do manual therapies help low back pain? A comparative effectiveness meta-analysis. Spine J 2014;39:E463–72. 10.1097/BRS.0000000000000230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sveinsdottir V, Eriksen HR, Reme SE. Assessing the role of cognitive behavioral therapy in the management of chronic nonspecific back pain. J Pain Res 2012;5:371–80. 10.2147/JPR.S25330 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang X-Q, Zheng J-J, Yu Z-W et al. A meta-analysis of core stability exercise versus general exercise for chronic low back pain. PLoS ONE 2012;7:e52082 10.1371/journal.pone.0052082 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vibe Fersum K, O'Sullivan P, Skouen JS et al. Efficacy of classification-based cognitive functional therapy in patients with non-specific chronic low back pain: a randomized controlled trial. Eur J Pain 2013;17:916–28. 10.1002/j.1532-2149.2012.00252.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.O'Sullivan K, Dankaerts W, O'Sullivan L et al. The effectiveness of a novel multidimensional behavioural-based intervention on people with non-specific chronic low back pain: a multiple case cohort study. Physical Therapy (in press). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Carr JL, Klaber Moffett JA, Howarth E et al. A randomized trial comparing a group exercise programme for back pain patients with individual physiotherapy in a severely deprived area. Disabil and Rehabil 2005;27:929–37. 10.1080/09638280500030639 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chown M, Whittamore L, Rush M et al. A prospective study of patients with chronic back pain randomised to group exercise, physiotherapy or osteopathy. Physiotherapy 2008;94:21–8. 10.1016/j.physio.2007.04.014 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cecchi F, Molino-Lova R, Chiti M et al. Spinal manipulation compared with back school and with individually delivered physiotherapy for the treatment of chronic low back pain: a randomized trial with one-year follow-up. Clin Rehabil 2010;24:26–36. 10.1177/0269215509342328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Critchley DJ, Ratcliffe J, Noonan S et al. Effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of three types of physiotherapy used to reduce chronic low back pain disability: a pragmatic randomized trial with economic evaluation. Spine J 2007;32:1474–81. 10.1097/BRS.0b013e318067dc26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fransen M, Crosbie J, Edmonds J. Physical therapy is effective for patients with osteoarthritis of the knee: a randomized controlled clinical trial. J Rheumatol 2001;28:156–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gustavsson C, Denison E, Koch Lv. Self-management of persistent neck pain: a randomized controlled trial of a multi-component group intervention in primary health care. Eur J Pain 2010;14:630.e1–11. 10.1016/j.ejpain.2009.10.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hudson JS, Ryan CG. Multimodal group rehabilitation compared to usual care for patients with chronic neck pain: a pilot study. Man Ther 2010;15:552–6. 10.1016/j.math.2010.06.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ko V, Naylor J, Harris I et al. One-to-one therapy is not superior to group or home-based therapy after total knee arthroplasty a randomized, superiority trial. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2013;95: 1942–9. 10.2106/JBJS.L.00964 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lansinger B, Carlsson JY, Kreuter M et al. Health-related quality of life in persons with long-term neck pain after treatment with qigong and exercise therapy respectively. Eur J Physiother 2013;15:111–17. 10.3109/21679169.2013.805816 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mannion A, Müntener M, Taimela S et al. Comparison of three active therapies for chronic low back pain: results of a randomized clinical trial with one-year follow-up. Rheumatology 2001;40:772–8. 10.1093/rheumatology/40.7.772 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.McLean SM, Klaber Moffett JA, Sharp DM et al. A randomised controlled trial comparing graded exercise treatment and usual physiotherapy for patients with non-specific neck pain (The GET UP neck pain trial). Man Ther 2013;18:199–205. 10.1016/j.math.2012.09.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Unsgaard-Tøndel M, Fladmark AM, Salvesen Ø et al. Motor control exercises, sling exercises, and general exercises for patients with chronic low back pain: a randomized controlled trial with 1-year follow-up. Phys Ther 2010;90:1426–40. 10.2522/ptj.20090421 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Artus M, van der Windt D, Jordan KP et al. The clinical course of low back pain: a meta-analysis comparing outcomes in randomised clinical trials (RCTs) and observational studies. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2014;15:68 10.1186/1471-2474-15-68 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Henry SM, Van Dillen LR, Ouellette-Morton RH et al. Outcomes are not different for patient-matched versus nonmatched treatment in subjects with chronic recurrent low back pain: a randomized clinical trial. Spine J 2014;14:2799–810. 10.1016/j.spinee.2014.03.024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hill JC, Whitehurst DG, Lewis M et al. Comparison of stratified primary care management for low back pain with current best practice (STarT Back): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2011;378:1560–71. 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60937-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Michaleff ZA, Maher CG, Lin CWC et al. Comprehensive physiotherapy exercise programme or advice for chronic whiplash (PROMISE): a pragmatic randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2014;384:133–41. 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60457-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rantonen J, Vehtari A, Karppinen J et al. Face-to-face information combined with a booklet versus a booklet alone for treatment of mild low-back pain: a randomized controlled trial. Scand J Work Environ Health 2014;40:156–66. 10.5271/sjweh.3398 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Fairbank JC, Pynsent PB. The Oswestry disability index. Spine 2000;25:2940–53. 10.1097/00007632-200011150-00017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.O'Sullivan P. Diagnosis and classification of chronic low back pain disorders: maladaptive movement and motor control impairments as underlying mechanism. Man Ther 2005;10:242–55. 10.1016/j.math.2005.07.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Dankaerts W, O'Sullivan P, Burnett A et al. The use of a mechanism-based classification system to evaluate and direct management of a patient with non-specific chronic low back pain and motor control impairment—a case report. Man Ther 2007;12:181–91. 10.1016/j.math.2006.05.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Chilton R, Pires-Yfantouda R, Wylie M. A systematic review of motivational interviewing within musculoskeletal health. Psychol Health Med 2012;17:392–407. 10.1080/13548506.2011.635661 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Fuentes J, Armijo-Olivo S, Funabashi M et al. Enhanced therapeutic alliance modulates pain intensity and muscle pain sensitivity in patients with chronic low back pain: an experimental controlled study. Phys Ther 2014;94:477–89. 10.2522/ptj.20130118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Nijs J, Paul van Wilgen C, Van Oosterwijck J et al. How to explain central sensitization to patients with ‘unexplained'chronic musculoskeletal pain: practice guidelines. Man Ther 2011;16:413–18. 10.1016/j.math.2011.04.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Moffett JK, Torgerson D, Bell-Syer S et al. Randomised controlled trial of exercise for low back pain: clinical outcomes, costs, and preferences. BMJ 1999;319:279–83. 10.1136/bmj.319.7205.279 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Jensen MP, Turner JA, Romano JM et al. Comparative reliability and validity of chronic pain intensity measures. Pain 1999;83:157–62. 10.1016/S0304-3959(99)00101-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Bostick G, Schopflocher D, Gross D. Validity evidence for the back beliefs questionnaire in the general population. Eur J Pain 2013;17:1074–81. 10.1002/j.1532-2149.2012.00275.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Waddell G, Newton M, Henderson I et al. A Fear-Avoidance Beliefs Questionnaire (FABQ) and the role of fear-avoidance beliefs in chronic low back pain and disability. Pain 1993;52:157–68. 10.1016/0304-3959(93)90127-B [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Harland NJ, Georgieff K. Development of the coping strategies questionnaire 24, a clinically utilitarian version of the coping strategies questionnaire. Rehabil Psychol 2003;48:296 10.1037/0090-5550.48.4.296 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Di Pietro F, Catley MJ, McAuley JH et al. Rasch analysis supports the use of the pain self-efficacy questionnaire. Phys Ther 2014;94:91–100. 10.2522/ptj.20130217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Eriksen HR, Ihlebæk C, Ursin H. A scoring system for subjective health complaints (SHC). Scand J of Public Health 1999;27:63–72. 10.1177/14034948990270010401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Lovibond S, Lovibond P. Manual for the Depression Anxiety and Stress Scales (DASS) 1993. Retrieved October 2014;23.

- 72.Marshall GN, Hays RD. The patient satisfaction questionnaire short-form (PSQ-18). 1994.

- 73.Rannestad T, Skjeldestad FE. Socioeconomic conditions and number of pain sites in women. BMC women's health 2012;12:7 10.1186/1472-6874-12-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Linton SJ, Nicholas M, MacDonald S. Development of a short form of the Örebro Musculoskeletal Pain Screening Questionnaire. Spine J 2011;36:1891–5. 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181f8f775 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Crawford JO. The Nordic musculoskeletal questionnaire. Occup Med 2007;57:300–1. 10.1093/occmed/kqm036 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Houben R, Ostelo RW, Vlaeyen JW et al. Health care providers’ orientations towards common low back pain predict perceived harmfulness of physical activities and recommendations regarding return to normal activity. Eur J Pain 2005;9:173–83. 10.1016/j.ejpain.2004.05.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Mutsaers J-H, Peters R, Pool-Goudzwaard A et al. Psychometric properties of the pain attitudes and beliefs scale for physiotherapists: a systematic review. Man Ther 2012;17:213–18. 10.1016/j.math.2011.12.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Smucker DR, Konrad TR, Curtis P et al. Practitioner self-confidence and patient outcomes in acute low back pain. Arch Fam Med 1998;7:223–8. 10.1001/archfami.7.3.223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Pincus T, Vogel S, Santos R et al. The attitudes to back pain scale in musculoskeletal practitioners (ABS-mp): the development and testing of a new questionnaire. Clin J Pain 2006;22:378–86. 10.1097/01.ajp.0000178223.85636.49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Catley MJ, O'Connell NE, Moseley GL. How good is the neurophysiology of pain questionnaire? A Rasch analysis of psychometric properties. J Pain 2013;14:818–27. 10.1016/j.jpain.2013.02.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Bishop A, Foster NE, Thomas E et al. How does the self-reported clinical management of patients with low back pain relate to the attitudes and beliefs of health care practitioners? A survey of UK general practitioners and physiotherapists. Pain 2008;135:187–95. 10.1016/j.pain.2007.11.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Hall AM, Ferreira ML, Clemson L et al. Assessment of the therapeutic alliance in physical rehabilitation: a RASCH analysis. Disabil Rehabil 2012;34:257–66. 10.3109/09638288.2011.606344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Makoul G, Krupat E, Chang C-H. Measuring patient views of physician communication skills: development and testing of the Communication Assessment Tool. Patient Educ Couns 2007;67:333–42. 10.1016/j.pec.2007.05.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Bombardier C, Hayden J, Beaton DE. Minimal clinically important difference. Low back pain: outcome measures. J Rheumatol 2001;28:431–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J Pers Soc Psychol 1986;51:1173–82. 10.1037/0022-3514.51.6.1173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.R. A language and environment for statistical computing [program] Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 87.Sandelowski M, Barroso J. Handbook for synthesizing qualitative research. Springer Publishing Company, 2007. [Google Scholar]