Abstract

Glucocorticoids (GC) are used for intensive care unit (ICU) patients on several indications. We present a patient who was admitted to the ICU due to severe respiratory failure caused by bronchospasm requiring mechanical ventilation and treated with methylprednisolone 240 mg/day in addition to antibiotics and bronchiolytics. When the sedation was lifted on day 10, the patient was awake but quadriplegic. Blood samples revealed elevated muscle enzymes, electromyography showed myopathy, and a muscle biopsy was performed. Glucocorticoid-induced myopathy was suspected, GC treatment was tapered, and muscle strength gradually returned. The patient made full recovery from the quadriplegia a few months later.

Background

Glucocorticoids (GCs) can be used for intensive care unit (ICU) patients for many reasons. Besides the positive effects of the treatment, it is well known that GCs, by themselves, induce muscle catabolism, inhibit anabolism and may cause myopathy.1 There is substantial controversy regarding the role of systemic GCs in ICU-acquired weakness (ICU-AW), but the use of GCs may have a negative impact on the duration of mechanical ventilation (MV).2

Glucocorticoid-induced myopathy (GIM) is often an unnoticed condition in the ICU, and the incidence of GIM is largely unknown.3 GIM is associated with delayed weaning from MV, and significant increase in length of ICU stay, and, consequently, more expenses. The clinical presentation is most often insidious, although it can be acute, particularly when high-doses of GCs are used.3 There is no specific treatment for GIM other than discontinuing GC treatment with respect of the underlying diseases. The objective of this case is to draw attention to GIM in the ICU.

Case presentation

A 53-year-old woman was admitted to the ICU due to acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease requiring MV. There was no sign of infection. Her medical history included using small doses of prednisolone related to her chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, but not the use of statins or other known drugs that could induce myopathy. Initially, she was treated with methylprednisolone 80 mg intravenously per day, in addition to bronchiolytics, and sedation. Owing to refractory bronchospasm, treatment was increased to methylprednisolone 240 mg/day. As her respiratory condition improved, the sedation was lifted and on day 10 she appeared fully awake but quadriplegic. After suspicion of GIM, GC treatment was tapered.

Investigations

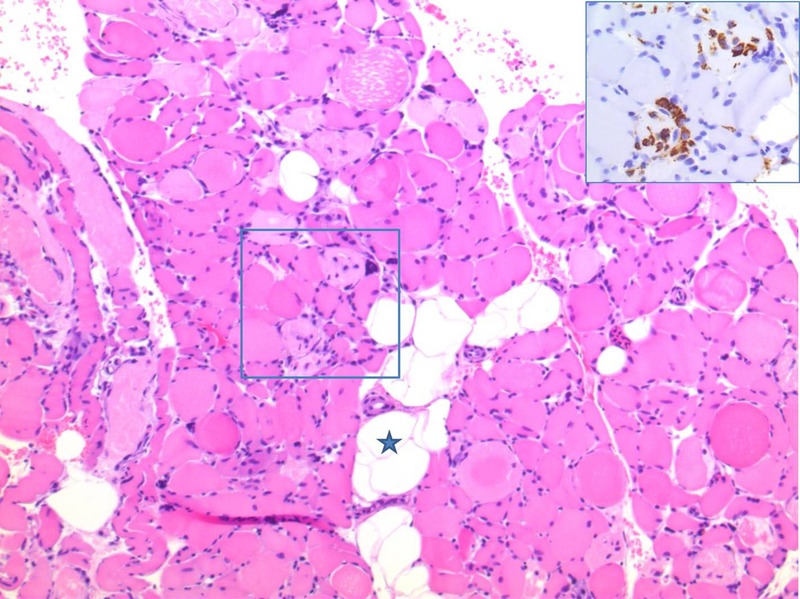

Eleven days after the ICU admission, electromyography (EMG) was performed. The EMG showed normal nerve conduction velocities and signal propagation, but significantly reduced evoked muscle amplitudes, suggesting myopathy. Creatine kinase and myoglobin peaked at 3672 U/L (24–77 U/I) and 12 500 µg/L (40–280 µg/L), respectively, at day 14 after the ICU admission. A muscle biopsy was performed and showed highly pathological muscle morphology: the majority of the muscle fibres were atrophic with varying muscle fibre diameter. In addition, many muscle fibres were necrotic with loss of striation. Some of the degenerating fibres were undergoing myophagocytosis with infiltrating macrophages. The general conclusion was necrotising myopathy (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Muscle biopsy with fatty infiltration (asterisk). There is variation in muscle fibre size, and many fibres are necrotic. Some of the degenerating fibres are undergoing myophagocytosis with infiltrating macrophages (H&E staining). Insert: Parallel section stained with CD68, highlighting the infiltrating macrophages.

Differential diagnosis

There are several causes of myopathy in the ICU, among which critical illness myopathy (CIM) is by far the most frequent. Myopathies that result from underlying endocrine or electrolyte abnormality should be ruled out, as well as other drug-induced or toxin-induced myopathies. Control of underlying infection is important for bacterial, parasitic, viral or spirochete-related myopathies. GIM is the most common form of drug-induced myopathy and occurs as a side effect of exogenous GC excess or possible endogenous hypercortisolism. However, other causes of drug-induced myopathies such as statins, antipsychotics and neuromuscular blocking agents, are important to consider. A muscle biopsy can help to differentiate between the histological subtypes of myopathies.

Treatment

There is no specific treatment for GIM other than tapering GC treatment if the underlying diseases permit this. Possible underlying aetiology of endogenous GCs should be ruled out. If endogenous hypercortisolism is present, it will be mandatory to treat this condition. To ensure maximum functional status of the ICU patient, it would be rational to aggressively treat the infection, apply minimal sedation regimes and spontaneous trails. Supplementary, early and aggressive physiotherapeutic intervention can be added to treat, or prevent, further muscle weakness.4

Outcome and follow-up

After tapering of GCs, muscle strength gradually returned and the patient gained full recovery from the quadriplegia. Muscle enzymes rapidly decreased and were normalised at discharge from the ICU. After 40 days in the ICU, the patient was transferred for further medical treatment and rehabilitation.

Discussion

ICU-AW is a term for all AW in the ICU.5 The most common reasons for ICU-AW is critical illness polyneuropathy (CIP) and CIM, or a combination of both.4 CIP appears to be a complication of severe sepsis representing a neurological manifestation of the systemic inflammatory response syndrome.4 CIM is an acute primary myopathy defined as a syndrome with a continuum of various morphological forms.2 The trigger factor for CIP and CIM is critical illness. It is important to be aware that GIM is not a subform of CIM, even though the clinical symptoms mimic it. GIM is a drug-induced myopathy, in fact, the most common form of drug-induced myopathy and triggered by GC excess. The condition can exist inside and outside the ICU.6 If only GIM is present, EMG and nerve conduction will show normal nerve conduction velocities and signal propagation, but with reduced muscle amplitudes suggesting myopathy. GIM is clinically characterised by severe muscle weakness extended to paralysis,6 and appears in a chronic form as well as an acute form.1 The chronic form occurs weeks or months after initiation of GC treatment and has a typical pattern of muscle weakness affecting the lower and the proximal part of the limbs.6 The acute form of GIM most often occurs in the ICU setting,3 and is typically noticed 5–7 days after initiation of high-dose GC treatment.6 Immobilisation, by itself, is probably a strong factor for GIM developing. Rhabdomyolysis can indicate development of acute GIM, but is not mandatory.3 There is no definitive diagnostic test for GIM, but a muscle biopsy could be helpful.

Muscle biopsies from patients suffering from myopathy in the ICU will often result in a mixed morphological answer varying between three histological subtypes. (1) Minimal change, or cachectic myopathy, characterised by muscle fibres showing calibre variations, angulations, internalised nuclei, fatty degeneration and fibrosis. (2) Thick filament myopathy, characterised by selective proteolysis and loss of myosin filaments. (3) Acute necrotising myopathy, characterised by muscle fibre vacuolisation and phagocytosis of myocytes.7 8 The latter two histological subtypes are seen in GIM.

Few similar case reports have been published regarding GIM in the ICU. Common for all the cases are that the patients received GCs in high doses (>60 mg methylprednisolone/d) for several days. All patients had general muscle weakness variable to quadriplegia and prolonged weaning from MV. In these cases, EMG showed reduced motor response. Muscle biopsies revealed scattered atrophic muscle fibres with internal nuclei and vacuolation and necrotic changes.3 9–11 A prospective study has shown that administration of GCs was the single largest independent predictor for developing ICU-AW, but the incidence of GIM was not monitored.3

There is no definitive diagnostic test for GIM. Therefore, it is based on the history, exposure to GCs and the absence of other causes of myopathies. The diagnosis is established by demonstrating improved muscle strength after discontinuing GC treatment.7 8

Learning points.

- The first sign of glucocorticoid-induced myopathy (GIM) in the intensive care unit (ICU) is often:

- General muscle weakness.

- Prolonged weaning from mechanical ventilation.

- GIM increases:

- Weaning time from respirator.

- Length of stay in the ICU.

- ICU cost.

- Mortality.

Diagnostics include medical history, electromyography, blood tests (creatine kinase and myoglobin) and a muscle biopsy.

Treatment includes discontinuing glucocorticoids treatment in respect to the underlying diseases.

Footnotes

Contributors: The suspicion of glucocorticoid-induced myopathy was raised in an interprofessional collaboration between the doctors and the nurse (HSE, HWH and AØL). The muscle biopsy was conducted and performed by ELL to help in diagnosing the condition. All authors made a contribution the scientific writing.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Pereira RM, Freire de Carvalho J. Glucocorticoid-induced myopathy. Joint Bone Spine 2011;78:41–4. 10.1016/j.jbspin.2010.02.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Latronico N, Tomelleri G, Filosto M. Critical illness myopathy. Curr Opin Rheumatol 2012;24:616–22. 10.1097/BOR.0b013e3283588d2f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Amaya-Villar R, Garnacho-Montero J, Garcia-Garmendia JL et al. Steroid-induced myopathy in patients intubated due to exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Intensive Care Med 2005;31:157–61. 10.1007/s00134-004-2509-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ydemann M, Eddelien HS, Lauritsen AO. Treatment of critical illness polyneuropathy and/or myopathy—a systematic review. Dan Med J 2012;59:A4511. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.De Jonghe B, Sharshar T, Lefaucheur JP et al. Paresis acquired in the intensive care unit: a prospective multicenter study. JAMA 2002;288:2859–67. 10.1001/jama.288.22.2859 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Minetto MA, Lanfranco F, Motta G et al. Steroid myopathy: some unresolved issues. J Endocrinol Invest 2011;34:370–5. 10.1007/BF03347462 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Friedrich O, Fink RH, Hund E. Understanding critical illness myopathy: approaching the pathomechanism. J Nutr 2005;135:1813S–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Friedrich O. Critical illness myopathy: what is happening? Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care 2006;9:403–9. 10.1097/01.mco.0000232900.59168.a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Polsonetti BW, Joy SD, Laos LF. Steroid-induced myopathy in the ICU. Ann Pharmacother 2002;36:1741–4. 10.1345/aph.1C095 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hanson P, Dive A, Brucher JM et al. Acute corticosteroid myopathy in intensive care patients. Muscle Nerve 1997;20:1371–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ramsay DA, Zochodne DW, Robertson DM et al. A syndrome of acute severe muscle necrosis in intensive care unit patients. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 1993;52:387–98. 10.1097/00005072-199307000-00006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]