Abstract

A highly potent secondary metabolite producing endophytic strain, Streptomyces sp. HUST012 was isolated from the stems of the medicinal plant Dracaena cochinchinensis Lour. Strain HUST012 showed antimicrobial and antitumor activities which were significantly much higher than those of dragon's blood extracted from D. cochinchinensis Lour. On further analysis, the strain was found to produce two metabolites, SPE-B11.8 (elucidated to be a novel metabolite (Z)-tridec-7-ene-1,2,13-tricarboxylic acid) and SPE-B5.4 (elucidated as Actinomycin-D). The Minimum Inhibitory Concentration values of SPE-B11.8 against a set of test bacterial organisms (Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus epidermis ATCC 35984, Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 25923, Escherichia coli ATCC 25922, and Klebsiella pneumoniae ATCC 13883) ranged between 15.63 and 62.5 μg/ml while that for SPE-B5.4 ranged between 0.04 and 2.24 μg/ml. The compound SPE-B11.8 showed cytotoxic effect at 41.63 and 29.54 μg/ml IC50-values against Hep G2 and MCF-7, respectively, while the compound SPE-B5.4 exhibited stronger activities against them at 0.23 and 0.18 μg/ml IC50-values.

Keywords: endophytic; Streptomyces sp. HUST012; Dracaena cochinchinensis Lour.; antimicrobial and cytotoxic activities; (Z)-tridec-7-ene-1,2,13-tricarboxylic acid; Actinomycin-D

Introduction

Streptomyces spp. have been shown to possess the ability to synthesize antibacterial, antifungal, insecticidal, antitumor, anti-inflammatory, anti-parasitic, antiviral, anti-infective, antioxidant, and herbicidal compounds (Qin et al., 2011; Kawahara et al., 2012). Nearly 70% of the natural antibiotics used in clinical practices were produced by actinobacteria (Subramani and Aalbersberg, 2012) of which 75–80% have been derived from Streptomyces alone (Inbar and Lapidot, 1988; Olano et al., 2004; Rehm et al., 2009; Crnovcic et al., 2013).

The plant Dracaena cochinchinensis Lour. has been used as a traditional medicine since ancient times in the form of Dragon's blood, a deep red resin. Dragon's blood has been shown to illustrate antimicrobial, antiviral, antitumor, cytotoxic, analgesic, antioxidative, anti-inflammatory, haemostatic, antidiuretic, anti-ulcer and wound healing activities (Gupta et al., 2008). It also finds application as coloring materials and wood varnish (Gupta et al., 2008). However, the slow growth in combination with its low dragon's blood yield results in the destruction of large number of century old plant for harvesting a few milligrams of dragon's blood (Fan et al., 2008). This current study was conducted to explore a sustainable way of utilizing the medicinal plant by studying the endophytic actinomycetes associated with the plant. This paper incorporated the results of the characterization and the evaluation of cytotoxic and antimicrobial effects of an endophytic Streptomyces sp. strain, isolated from the medicinal plant D. cochinchinensis Lour. in comparison with those of dragon's blood extracted from the host plant. The paper also reported the structure elucidation of the bioactive metabolites extracted from the endophytic actinobacteria.

Materials and methods

Sample collection and isolation of endophytic actinomycete

Healthy stems of D. cochinchinensis Lour. plant were collected from Cuc Phuong National Park, Ninh Binh province, Vietnam (20° 19′ 8″N, 105° 37′ 20″E; 338 m). The samples were surface sterilized and plated on Sodium propionate medium (Qin et al., 2009). The medium was supplemented with nalidixic acid (25 mg/l), nystatin (50 mg/l), and K2Cr2O7 (50 mg/l) to inhibit the growth of Gram-negative bacteria and fungi and polyvinyl pyrolidone (PVP) 2% and tannase 0.005% to improve the growth of colonies. Actinomycetes colonies grown on this culture media were selected and purified by repeated streaking onto International Streptomyces Project (ISP) 2 medium. The purified strain HUST012 was preserved as glycerol suspensions (20%, v/v) and as lyophilized spore suspensions in skim milk at −80°C (Zhang et al., 2010).

Characterization of the endophytic isolate HUST012

The endophytic isolate HUST012 was characterized on the basis of the physiological and biochemical properties and the analysis of 16S rRNA gene sequence. Morphological and growth patterns were observed on different media (Shirling and Gottlieb, 1966). Morphological characteristics were observed by light microscopy (Olympus BH2) and scanning electron microscopy (JSM-6610LV, JEOL Ltd.) (Anderson and Wellington, 2001). The ability of the isolate to grow at different pH (4.0–10.0, at intervals of 1.0 pH unit using the buffer system as described by Xu et al., 2005) and concentration of NaCl (0, 0.5, 1.0, 2.0, 3.0, 4.0, 5.0, 6.0, 7.0, 10.0, 11.0, 12.0, 15.0%, w/v) was examined on ISP 2 medium. Growth was tested at 4, 10, 20, 25, 28, 37, 45, and 55°C using ISP2 medium. The hydrolysis of starch, casein and gelatin was carried out according to the methods described by Tindall et al. (2007). Nitrate reduction and H2S production were determined using conventional procedures (Goodfellow, 1971; Athalye et al., 1985). Utilization of the carbon source was performed as previously described (Shirling and Gottlieb, 1966; Athalye et al., 1985; Mechri et al., 2014) using the basal medium recommended by Pridham and Gottlieb (1948).

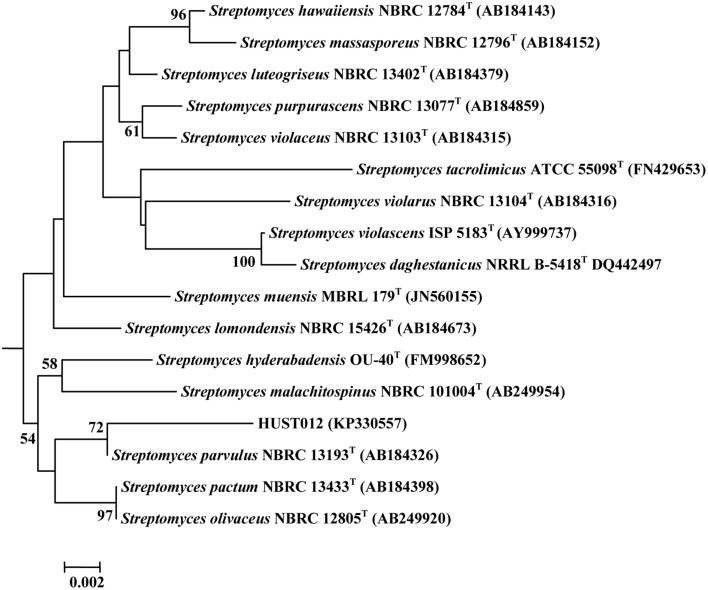

The isolation of genomic DNA and PCR amplification for 16S rRNA gene was performed as previously described (Li et al., 2009). The identification of phylogenetic neighbors and calculation of pairwise 16S rRNA gene sequence similarities were achieved using the EzTaxon server (http://www.eztaxon.org/) (Kim et al., 2012) and BLAST analysis (http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nihgov/Blast.cgi). Multiple sequence alignment was done using CLUSTALW (Thompson et al., 1997). The phylogenetic tree was constructed using the aligned sequences by the neighbor-joining method (Saitou and Nei, 1987) using Kimura-2-parameter distances (Kimura, 1983) in the MEGA 6 software (Tamura et al., 2013). To determine the support of each clade, bootstrap analysis was performed with 1000 replications (Felsenstein, 1985).

The GenBank accession number for the partial 16S rRNA gene sequences of strain HUST012 is KP330557.

Evaluation of antimicrobial activities

The antibacterial activities was evaluated against Methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus (MSSA) ATCC 29213, Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus epidermidis (MRSE) ATCC 35984, Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) ATCC 25923, Klebsiella pneumoniae ATCC 13883, Aeromonas hydrophila ATCC 7966, Escherichia coli ATCC 25922, Escherichia coli ATCC 11105, and Enterococcus faecalis ATCC 29212 using the agar well diffusion method (Holder and Boyce, 1994). The Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) was determined as previously described (Andrews, 2001).

The animal fungal pathogens Fusarium graminearum, Aspergillus carbonarius, and Aspergillus westerdijkiae which were known to produce strong toxic deoxynivalenol (DON) and ochratoxin A (Khamna et al., 2009; Huffman et al., 2010) were kindly provided by UMR Qualisud, CIRAD, France. These strains were maintained on Potato Dextrose Agar (PDA) medium (Liu et al., 2002). For the determination of antifungal activity, culture broth of HUST012 (100 ml) was centrifuged at 7000 g for 10 min. The supernatant was collected and added to the PDA medium (pH 5.5) at a concentration of 15% (v/v). Sterilized water was used as control. The resulting PDA plates were inoculated with the different fungal strains and incubated for 5 days at 28°C. The fungal radial growth was measured. Each experiment was carried out in triplicates.

Determination of cytotoxic activity

The cytotoxicity against human hepatocellular carcinoma Hep G2 and human breast adenocarcinoma MCF-7 cell lines was tested by using sulforhodamine B (SRB) assay as previously described (Thao et al., 2014). Ellipcitine was used as the positive control. The test was done in triplicates to ensure accuracy.

Fermentation

A small-scale liquid fermentation was performed with YIM 61 medium (Qin et al., 2009) as the antibiotic producing medium (200 rpm, 28°C, 5 days). The scale up fermentation (20 L) was done using the New Brunswick BioFlo®/CelliGen® 115 Benchtop Fermentor & Bioreactor (28°C, 5 days). In both cases, seed culture for inoculation was prepared in ISP2 medium (200 rpm, 28°C, 4 days)

Extraction and purification of the active compounds

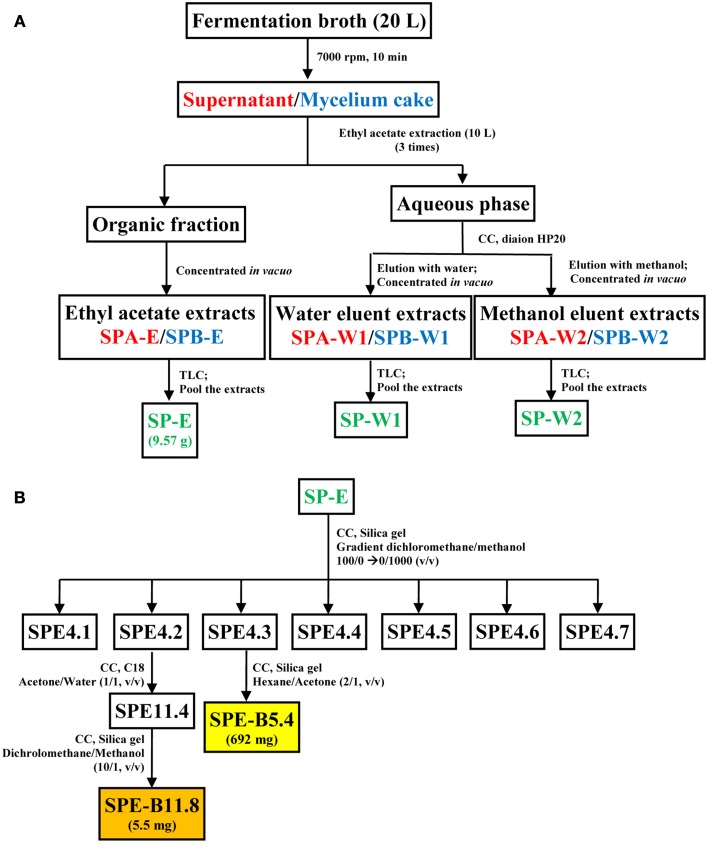

The fermentation broth was centrifuged at 7000 rpm for 10 min. The supernatant fraction was then extracted thrice with ethyl acetate. The ethyl acetate layer was concentrated in vacuo to give ethyl acetate extract (SPA-E). The aqueous phase was filtered through a diaion HP20 column and eluted with water and methanol subsequently. The water eluent fraction was evaporated to give the extract designated as SPA-W1 while the methanol eluent was concentrated in vacuo to obtain a brown solid (SPA-W2).

Similarly, the mycelium cake obtained after centrifugation of the fermentation broth was processed to obtain a ethyl-acetate extract (SPB-E), a water eluent extract (EPB-W1) and a methanol eluent extract (SPB-W1). All these fractions were analyzed in Silica gel TLC sheet (Merck, Germany) using the dichloromethane-methanol (30:1, v/v) solvent system. Based on the similarity profiles in the TLC (Koup et al., 1978), SPA-E/SPB-E, SPA-W1/SPB-W1, and SPA-W2/SPB-W2 were pooled together and were designated as SP-E, SP-W1, and SP-W2, respectively. A schematic diagram representing the extraction protocol is shown in Figure 1. Each of these fractions was evaluated for antimicrobial and cytotoxic activities. The bioactive fractions were further purified using different solvent systems to obtain pure metabolite(s) as represented in Figure 1B.

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of the process for metabolite extraction from strain HUST012. (A) Extraction of the fermentation medium into crude metabolite extracts; (B) fractionation protocol for pure compounds SPE-B11.8 and SPE-B5.4 from the crude ethyl acetate extract. Note: CC, Column chromatography; Font in red color indicates supernatant, blue mycelium and green pooled fractions; Color boxes indicate pure compound.

Structure elucidation of the pure active compounds

The structure of the bioactive compound(s) was analyzed using mass spectrometry (MS) and nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy (Booth et al., 1976; Hamza et al., 2013). The results were compared with the available reference compounds and published literatures.

Determination of antibacterial and cytotoxic effects of the dragon's blood extracted from medicinal plant D. cochinchinensis

Dragon's blood in the xylem of the host plant was extracted as described by Wang et al. (2011). The dry weight of the extract was dissolved in 95% (v/v) alcohol and filtered through sterile filter membrane (0.22 μm). The solution was then used for antibacterial and antitumor tests.

The MIC of Dragon's blood against MSSA ATCC 29213, MRSE ATCC 35984, K. pneumoniae ATCC 13883, and E. coli ATCC 25922 was determined by broth dilution method on 96-well plate as previously described (Andrews, 2001). The MIC against F. graminearum was determined according to Gopal et al. (2012). The SRB assay was used for determination the cytotoxic effect of the Dragon's blood on human breast adenocarcinoma (MCF-7) and human hepatocellular carcinoma (Hep G2) cells (Thao et al., 2014).

Results

Characterization of strain HUST012

Cells of the strain HUST012 was Gram-positive and aerobic. The strain formed extensively branched, non-fragmented substrate and aerial mycelia. Strain HUST012 formed straight or rectiflexibile spore chains with smooth surface. However, these spore chains generally contained less than 50 spores (Figure S1). The strain grew well on ISP 2, ISP 3, ISP 5, TSA, Czapek, and Nutrient agar media, with a gray color aerial mycelium. It produced green-yellow and yellow pigments on ISP2 and Czapek agar media respectively. Strain HUST012 was found to grow over a wide range of temperature (4–45°C) and pH (4.0–9.0) with optimal growth at 28°C and pH 6.0–7.0, and in the presence of upto 10% NaCl (w/v) with optimum at 1–3% NaCl.

HUST012 could utilize DL-alanine, L-arginine, L-asparagine, Glycine, DL-leucine, L-lysine, DL-serine, L-glutamic acid, DL-methionine, L-cystine, L-histidine as nitrogen resources; D-fructose, D-galactose, D-glucose, D-mannose, D-trehalose, D-sorbose, D-xylose, glycerol, and sodium acetate as carbon sources. The strain was positive for amylase and catalase activities, but was negative for nitrate reduction, H2S production and gelatin reduction tests. Strain HUST012 showed highest 16S rRNA gene sequence similarities with Streptomyces parvulus (99.26%). Phylogenetic tree (Figure 2) based on neighbor-joining method also indicated its closest similarity to Streptomyces parvulus. The phenotypic and genomic data indicated that the strain HUST012 represented a strain of the genus Streptomyces for which the strain was referred to as Streptomyces sp. strain HUST012.

Figure 2.

Neighbor-joining tree showing the phylogenetic relationships based on 16S rRNA gene sequence of the strain HUST012 and closest species. Bootstrap values (expressed as percentages of 1000 replications) greater than 50% was given at the node.

Antimicrobial and cytotoxic effects of strain HUST012

The culture filtrate of strain HUST012 exhibited antibacterial activity against all tested Gram positive and Gram negative bacterial strains. The maximum activity was found against MRSE ATCC 35984 (inhibition zone of 35 mm diameter), followed by A. hydrophila ATCC 7966 (26 mm) and MSSA ATCC 29213 (25.80 mm). The detailed antimicrobial profiles are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Antimicrobial activities of the strain Streptomyces sp. HUST012 against bacterial and fungal strains.

| Test strains | Inhibition zone (mm diameter) |

|---|---|

| GRAM POSITIVE BACTERIA | |

| Methicillin-resistant S. epidermidis ATCC 35984 | 35.00 ± 0.80 |

| Methicillin-resistant S. aureus ATCC 25923 | 18.90 ± 1.67 |

| Methicillin-susceptible S. aureus ATCC 29213 | 25.80 ± 1.47 |

| Enterococcus faecalis ATCC 29212 | 20.00 ± 0.20 |

| GRAM NEGATIVE BACTERIA | |

| Escherichia coli ATCC 25922 | 18.90 ± 1.00 |

| Escherichia coli ATCC 11105 | 12.40 ± 0.73 |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae ATCC 13883 | 19.80 ± 2.20 |

| Aeromonas hydrophila ATCC 7966 | 26.00 ± 0.47 |

| FUNGAL STRAINS | |

| Fusarium graminearum | 9.70 ± 0.73 |

| Aspergillus westerdijkiae | 1.80 ± 0.47 |

| Aspergillus carbonarius | 7.70 ± 0.80 |

The antifungal activity of Streptomyces sp. strain HUST012 was examined against three mycotoxin producing fungal strains. The fungal growth inhibition was observed in the order: F. graminearum (9.7 mm), A. carbonarius (7.7 mm), and A. westerdijkiae (1.8 mm).

Fermentation, antimicrobial and cytotoxic effects of bioactive metabolites of strain HUST012

Among the crude metabolites extracts of strain HUST012, the fraction SP-E showed the highest antibacterial and cytotoxic activities. This fraction was further purified by column chromatography with different gradient solvent systems as depicted in Figure 1. Two bioactive metabolites, designated SPE-B11.8 and SPE-B5.4, were purified.

The MIC values of the metabolite SPE-B11.8 against the test bacterial organisms ranges between 15.63 and 62.5 μg/ml while those for SPE-B5.4 ranges between 0.04 and 2.24 μg/ml (Table 2).

Table 2.

Antibacterial and cytotoxic effects of the compounds HPE-B11.8 and SPE-B5.4 in comparison with Dragon's blood extracted from medicinal plant D. cochinchinensis Lour.

| Test organisms/cancer cell line | SPE-B11.8 | SPE-B5.4 | Dragon's blood extract |

|---|---|---|---|

| MIC/IC50 (μg/ml) | |||

| MRSE ATCC 35984 | 15.63 ± 1.18 | 0.04 ± 0.00 | 4.88 ± 0.05 |

| MRSA ATCC 25923 | 62.5 ± 2.26 | 0.04 ± 0.00 | 4.88 ± 0.05 |

| E. coli ATCC 25922 | Inactive | 2.24 ± 0.01 | 9.77 ± 0.23 |

| K. pneumoniae ATCC 13883 | 62.5 ± 2.26 | 0.04 ± 0.00 | 4.88 ± 0.05 |

| F. graminearum | Inactive | 9.77 ± 0.23 | 19.53 ± 0.80 |

| Hep G2 | 41.63 ± 0.61 | 0.23 ± 0.05 | 77.91 ± 0.22 |

| MCF-7 | 29.54 ± 2.89 | 0.18 ± 0.05 | 70.00 ± 7.08 |

Human hepatocellular carcinoma Hep G2 and human breast adenocarcinoma cell MCF-7 lines were used as model systems to examine the cytotoxic effect of Streptomyces sp. HUST012. The culture filtrate, crude metabolite extracts (SP-E, SP-W1, SP-W2) and the pure metabolites (SPE-B11.8 and SPE-B5.4) were examined for their cytotoxic effect on the two human cancer cell lines Hep G2 and MCF-7. The cytotoxic assay results showed that the culture filtrate of the strain HUST012 had significant inhibition toward Hep G2 and MCF-7 cells with IC50-values of 4 and 3 μg/ml, respectively. Among the crude metabolites extracts, SP-E showed the strongest cytotoxic effect with IC50-values of 0.31 and 0.18 μg/ml. The pure metabolites SPE-B11.8 showed cytotoxic effect at 41.63 and 29.54 μg/ml IC50-values against Hep G2 and MCF-7, respectively, while the metabolite SPE-B5.4 exhibited the same at 0.23 and 0.18 μg/ml IC50-values (Table 3).

Table 3.

Cytotoxicity of test sample (IC50 in μg/ml).

| Samples | Hep G2 | MCF-7 |

|---|---|---|

| Culture filtrate of HUST012 | 4.00 ± 0.10 | 3.00 ± 0.10 |

| SP-E | 0.31 ± 0.03 | 0.18 ± 0.02 |

| SP-W1 | >100 | >100 |

| SP-W2 | >100 | >100 |

| SPE-B11.8 | 41.63 ± 0.61 | 29.54 ± 2.89 |

| SPE-B 5.4 | 0.23 ± 0.05 | 0.18 ± 0.05 |

| Ellipticine | 0.51 ± 0.08 | 0.47 ± 0.05 |

Structure elucidation of bioactive compounds

The structure of the compounds SPE-B11.8 and SPE-B5.4 were analyzed through the techniques of MS and NMR spectroscopy.

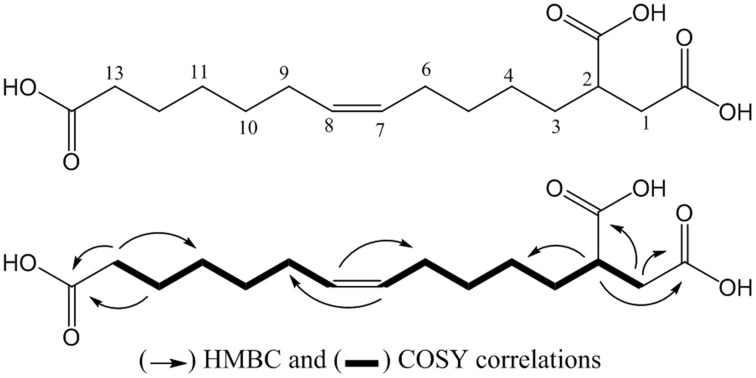

The compound SPE-B11.8 was obtained as a colorless solid. Its HRESIMS spectrum showed a peak at m/z 315.1814 [M+H]+, corresponding to the molecular formula C16H27O6. The 1D and 2D-NMR spectra of SPE-B11.8 showed signals characteristic for a monounsaturated fatty acid with the double bond at δH 5.33/δC129.1–129.9, three carboxylic groups at δC 175.1, 178.1, and 181.1, and a cluster of methylenic protons at δC in the range of δC 24.6–35.1. The COSY and HMBC spectra led to the identification of the fragments of SPE-B11.8 structure (see Figure S2 for the complete NMR spectra). The position of the double bond was also confirmed by the MS data with the fragment at m/z 128.08 and 187.08 corresponding to the breakdown at C-7 and C-8 liason. The configuration of the double bond was determined based the on the chemical shifts of vicinal carbon atoms. Both C-6 and C-9 appeared at δC 26.5 and 26.3 ppm indicating the Z configuration. Thus, compound SPE-B11.8 was newly elucidated to be (Z)-tridec-7-ene-1,2,13-tricarboxylic acid (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Structure of the compound SPE-B11.8 (elucidated as (Z)-tridec-7-ene-1,2,13-tricarboxylic acid).

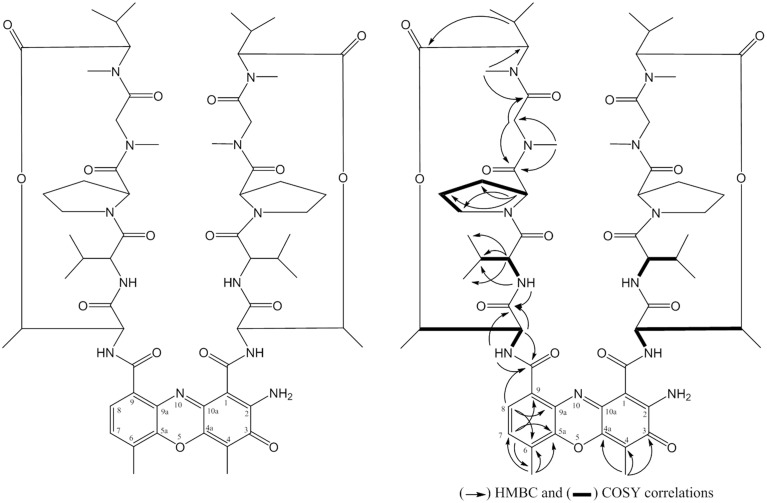

The compound SPE-B5.4 was obtained as a red powder, soluble in methanol, ethyl acetate, ethanol, and DMSO, stable in aqueous solutions at 5–10°C. The HRESIMS spectrum revealed a peak at m/z 1255.6435 [M+H]+, corresponding to the formula C62H87N12O16 (Figure S3). The 1H-NMR, 13C-NMR spectrum analysis data of the SPE-B5.4 compound is presented in Table S1. The spectral data was compared with the findings of Booth et al. (1976) and the compound SPEB-5.4 was identified as Actinomycin-D with molecular formula C62H86N12O16 (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Structure of the compound SPE-B3.4 (established as Actinomycin-D).

Antibacterial and cytotoxic effects of the dragon's blood extracted from medicinal plant D. cochinchinensis

The Dragon's blood extract was analyzed for its antibacterial and cytotoxic effects against MRSA, MRSE, K. pneumoniae and E. coli, and toward MCF-7 and Hep G2 cell lines. Table 2 showed the MIC for the dragon's blood extracts in comparison with those of the crude metabolites extracts and the compounds SPE-B11.8 and SPE-B5.4.

Discussion

The antimicrobial resistance has been one of the most serious health threats. Infections from resistant bacteria are now too common, and some pathogens have even become resistant to multiple classes of antibiotics. The decline of effective antibiotics will undermine our ability to fight infectious diseases and manage the infectious complications common in vulnerable patients, especially those undergoing chemotherapy for cancer, dialysis for renal failure, and organ transplantation. When first- and second-line antibiotic treatment options are limited by resistance and/or unavailability, healthcare providers are forced to use toxic antibiotics which are frequently more expensive but less effective. Even when alternative treatments are available, research has shown that patients with resistant infections are often much more likely to result in death, and that survivors require longer hospital stays, delayed recuperation, and long-term disability. Hence, there is an urgent need for search of novel drugs against such pathogens. It has been envisaged that endophytic environment is an extreme source to provide exciting new bioactive compounds.

In the present study, an attempt was tried to identify the bioactive potential of the endophytic actinobacterium Streptomyces sp. HUST012. The strain was found to exhibit antimicrobial activities against a set of pathogenic bacteria and fungi (Table 1). The presence of antifungal activities is also an indication of probable biocontrol mechanisms against mycotoxin producing fungal strains. Similar findings have been reported in similar studies of Streptomyces strains (Rahman et al., 2010; Usha et al., 2010; Naine et al., 2015).

The cytotoxic ability of this strain was significant as compared to that reported in previous studies on S. parvulus strain VITJS11 (Naine et al., 2015). The compounds SPE-B11.8 and SPE-B5.4 had IC50-values of 41.63 and 0.23 μg/ml on Hep G2 cells as compared to 500 μg/ml by S. parvulus strain VITJS11. Other reports showed that migrastatin, a secondary metabolite from Streptomyces inhibited the Hep G2 cells at the concentration of 6 and 10 μM after 24 and 48 h of treatment (Rambabu et al., 2014). The high bioactive effect of Streptomyces sp. HUST012 can be explained by the fact that endophytic actinomycetes live in close association with their host plants and that it could become a real possibility for exchange of genes involved in natural products biosynthesis between endophytic actinomycetes and host plants via horizontal gene transfer, resulting in synthesis of plant-derived compounds by a microbial endophyte (Chandra et al., 2013).

An important finding of this current study was the isolation of the new compound HPE-B11.8 which was elucidated as (Z)-tridec-7-ene-1,2,13-tricarboxylic acid, thereby underlying the importance of the source. The compound HPE-B11.8 possessed moderate antibacterial and anticancer activities against the test pathogenic microorganisms/cell lines. Another important finding was the isolation of Actinomycin D (compound SPE-B5.4). Actinomycin D was an antineoplastic antibiotic that inhibits cell proliferation. It finds wide range of applications, viz. as selective reagent in cell culture, studies in suppressing HIV-replication and programmed cell death of PC12 cells, and as an antibiotic in treatment of various malignant neoplasm including Wilm's tumor and the sarcomas. Actinomycin-D decreases Mcl-1 expression and acts synergistically with ABT-737 against small cell lung cancer cell lines (Aishan et al., 2010). According to the Internet bibliographic database-MEDLINE, actinomycins, especially Actinomycin-D, have been the subject of about 3300 research publications (Koba and Konopa, 2005). The isolation of Actinomycin-D is not a new discovery but our present study proved that the medicinal plant D. cochinchinensis Lour. was a rich source of endophytic actinomycetes producing the potent antibiotic agents.

Dragon's blood has been well documented for its antimicrobial, antioxidant, anti-antitumor and cytotoxic properties. However, the host plant D. cochinchinensis Lour. has no secretory tissue to release this useful metabolite, and therefore Dragon's blood remains in xylem parenchyma cells of the stem. The growth of the plant is extremely slow and has low yield of dragon's blood. To harvest a few pieces of resinous wood, a tree with hundreds of years old is often destroyed. This work aimed to evaluate the antimicrobial and cytotoxic effects of the natural Dragon's blood extracted from medicinal plant D. cochinchinensis Lour. in comparison with that secreted by the endophytic Streptomyces sp. HUST012 associated with the host plant. Our results were significant in comparison to the findings of other research groups (Al-Fatimi et al., 2005; Wang et al., 2010, 2011). This could give us a suggestion for the promotion of the application of secondary bioactive metabolites from endophytic actinomycetes associated with the medicinal plant D. cochinchinensis Lour. instead of destroying valuable endangered trees.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr. Samira Sarter (UMR QUALISUD, CIRAD, France) and Dr. Osama Abdalla Mohamed (Suez Canal University, Egypt) for their kind comments on this manuscript. This research was supported by Vietnam Ministry of Education and Training (B2014-01-79 project) and the Guangdong Province Higher Vocational Colleges & Schools Pearl River Scholar Funded Scheme (2014). The authors also thank to UMR QUALISUD, CIRAD, Montpellier, France for supporting the characterization of the HUST012 strain and determination of antifungal activity.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: http://journal.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fmicb.2015.00574/abstract

References

- Aishan H., Baba M., Iwasaki N., Kuang H., Okuyama T. (2010). The constituents of Urtica cannabina used in Uighur medicine. Pharm. Biol. 48, 577–583. 10.3109/13880200903214215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Fatimi M., Friedrich U., Jenett-Siems K. (2005). Cytotoxicity of plants used in traditional medicine in Yemen. Fitoterapia 76, 355–358. 10.1016/j.fitote.2005.02.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson A. S., Wellington E. M. (2001). The taxonomy of Streptomyces and related genera. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 51, 797–814. 10.1099/00207713-51-3-797 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrews J. M. (2001). Determination of minimum inhibitory concentrations. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 48, 5–16. 10.1093/jac/48.suppl_1.5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Athalye M., Goodfellow M., Lacey J., White R. P. (1985). Numerical classification of Actinomadura and Nocardiopsis. Int. J. Syst. Bact. 35, 86–98. 10.1099/00207713-35-1-86 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Booth H., Mauger A. B., Rzeszotarski W. J. (1976). A 13C NMR study of actinomycin D and related model peptides. Org. Magn. Reson. 8, 219–223. 10.1002/mrc.1270080413 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chandra S., Lata H., Varma A. (2013). Biotechnology for Medicinal Plants-Micropropagation and Improvement. Berlin; Heidelberg: Springer-Verleg. [Google Scholar]

- Crnovcic I., Vater J., Keller U. (2013), Occurrence and biosynthesis of C-demethylactinomycins in actinomycin-producing Streptomyces chrysomallus and Streptomyces parvulus. J. Antibiot. 66, 211–218. 10.1038/ja.2012.120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan L. L., Tu P. F., He J. X., Chen H. B., Cai S. Q. (2008). Microscopical study of original plant of Chinese drug “Dragon's Blood” Dracaena cochinchinensis and distribution and constituents detection of its resin. Zhongguo Zhong Yao Za Zhi 33, 1112–1117. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felsenstein J. (1985). Confidence limits on phylogenies: an approach using the bootstrap. Evolution 39, 783–791. 10.2307/2408678 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodfellow M. (1971). Numerical taxonomy of some nocardioform bacteria. J. Gen. Microbiol. 69, 33–80. 10.1099/00221287-69-1-33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gopal R., Na H., Seo C. H., Park Y. (2012). Antifungal activity of (KW)n or (RW)n peptide against Fusarium solani and Fusarium oxysporum. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 13, 15042–15053. 10.3390/ijms131115042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta D., Bleakley B., Gupta R. K. (2008). Dragon's blood: botany, chemistry and therapeutic uses. J. Ethnopharmacol. 115, 361–380. 10.1016/j.jep.2007.10.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamza A. A., Ali H. A., Clark B. R., Murphy C. D., Elobaid E. A. (2013). Isolation and characterisation of actinomycin D producing Streptomyces spp. from Sudanese soil. Afr. J. Biotechnol. 12, 2624–2632. 10.5897/AJB12.1066 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Holder I. A., Boyce S. T. (1994). Agar well diffusion assay testing of bacterial susceptibility to various antimicrobials in concentrations non-toxic for human cells in culture. Burns 20, 426–429. 10.1016/0305-4179(94)90035-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huffman J., Gerber R., Du L. (2010). Recent advancements in the biosynthetic mechanisms for polyketide-derived mycotoxins. Biopolymers 93, 764–776. 10.1002/bip.21483 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inbar L., Lapidot A. (1988). Metabolic regulation in Streptomyces parvulus during actinomycin D synthesis, studied with 13C- and 15N-labeled precursors by 13C and 15N nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy and by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry. J. Bacteriol. 170, 4055–4064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawahara T., Izumikawa M., Otoguro M., Yamamura H., Hayakawa M., Takagi M., et al. (2012). JBIR-94 and JBIR-125, Antioxidative phenolic compounds from Streptomyces sp. R56-07. J. Nat. Prod. 75, 107–110. 10.1021/np200734p [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khamna S., Yokota A., Lumyong S. (2009). Actinomycetes isolated from medicinal plant rhizospheric soils: diversity and screening of antifungal compounds, indole-3-acetic acid and siderophore production. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 25, 649–655. 10.1007/s11274-008-9933-x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kim O. S., Cho Y. J., Lee K., Yoon S. H., Kim M., Na H., et al. (2012). Introducing EzTaxon-e: a prokaryotic 16S rRNA gene sequence database with phylotypes that represent uncultured species. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 62, 716–721. 10.1099/ijs.0.038075-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura M. (1983). The Neutral Theory of Molecular Evolution. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Koba M., Konopa J. (2005). Actinomycin D and its mechanisms of action. Postepy Hig. Med. Dosw. 59, 290–298. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koup J. R., Brodsky B., Lau A., Beam T. R., Jr. (1978). High-performance liquid chromatographic assay of chloramphenicol in serum. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 14, 439–443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J., Zhao G. Z., Qin S., Zhu W. Y., Xu L. H., Li W. J. (2009). Streptomyces sedi sp. nov., isolated from surface-sterilized roots of Sedum sp. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 59, 1492–1496. 10.1099/ijs.0.007534-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y., Tortora G., Ryan M. E., Lee H. M., Golub L. M. (2002). Potato dextrose agar antifungal susceptibility testing for yeasts and molds: evaluation of phosphate effect on antifungal activity of CMT-3. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46, 1455–1461. 10.1128/AAC.46.5.1455-1461.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mechri B., Manga A. G. B., Tekaya M., Attia F., Cheheb H., Meriem F. B., et al. (2014). Changes in microbial communities and carbohydrate profiles induced by the mycorrhizal fungus (Glomus intraradices) in rhizosphere of olive trees (Olea europaea L.). Appl. Soil Ecol. 75, 124–133. 10.1016/j.apsoil.2013.11.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Naine S. J., Devi C. S., Mohanasrinivasan V., Vaishnavi B. (2015). Antimicrobial, antioxidant and cytotoxic activity of marine Streptomyces parvulus VITJS11 crude extract. Braz. Arch. Biol. Technol. 58, 198–207. 10.1509/S1516-8913201400173 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Olano C., Moss S. J., Braña A. F., Sheridan R. M., Math V., Weston A. J., et al. (2004). Biosynthesis of the angiogenesis inhibitor borrelidin by Streptomyces parvulus Tü4055: insights into nitrile formation. Mol. Microbiol. 52, 1745–1756. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04090.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pridham T. G., Gottlieb D. (1948). The utilization of carbon compounds by some Actinomycetales as an aid for species determination. J. Bacteriol. 56, 107–114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin S., Li J., Chen H. H., Zhao G. Z., Zhu W. Y., Jiang C. L., et al. (2009). Isolation, diversity, and antimicrobial activity of rare actinobacteria from medicinal plants of tropical rain forests in Xishuangbanna, China. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 75, 6176–6186. 10.1128/AEM.01034-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin S., Xing K., Jiang J. H., Xu L. H., Li W. J. (2011). Biodiversity, bioactive natural products and biotechnological potential of plant-associated endophytic actinobacteria. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 89, 457–473. 10.1007/s00253-010-2923-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahman M. A., Islam M. Z., Khondkar P., Islam M. A. U. (2010). Characterization and antimicrobial activities of a polypeptide antibiotic isolated from a new strain of Streptomyces parvulus. Bangladesh Pharm. J. 13, 14–17. [Google Scholar]

- Rambabu V., Suba S., Manikandan P., Vijayakumar S. (2014). Cytotoxic and apoptotic nature of migrastatin, a secondary metabolite from Streptomyces evaluated on HEP G2 cell line. Int. J. Pharm. Pharm. Sci. 6, 333–338. [Google Scholar]

- Rehm S., Han S., Hassani I., Sokocevic A., Jonker H. R., Engels J. W., et al. (2009). The high resolution NMR structure of parvulustat (Z-2685) from Streptomyces parvulus FH-1641: comparison with tendamistat from Streptomyces tendae 4158. Chembiochem 10, 119–127. 10.1002/cbic.200800547 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saitou N., Nei M. (1987). The neighbour-joining method: a new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Mol. Biol. Evol. 4, 406–425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shirling E. B., Gottlieb D. (1966). Methods for characterization of Streptomyces species. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 16, 313–340. 10.1099/00207713-16-3-313 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Subramani R., Aalbersberg W. (2012). Marine actinomycetes: an ongoing source of novel bioactive metabolites. Microbiol. Res. 167, 571–580. 10.1016/j.micres.2012.06.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamura K., Stecher G., Peterson D., Filipski A., Kumar S. (2013), MEGA6: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis version 6.0. Mol. Biol. Evol. 30, 2725–2729. 10.1093/molbev/mst197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thao D. T., Phuong D. T., Hanh T. T. H., Thao N. P., Cuong N. X., Nam N. H., et al. (2014). Two new neoclerodane diterpenoids from Scutellaria barbata D. Don growing in Vietnam. J. Asian Nat. Prod. Res. 16, 364–369. 10.1080/10286020.2014.882912 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson J. D., Gibson T. J., Plewniak F., Jeanmougin F., Higgins D. G. (1997). The CLUSTAL_X windows interface: flexible strategies for multiple sequence alignment aided by quality analysis tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 25, 4876–4882. 10.1093/nar/25.24.4876 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tindall B. J., Sikorski J., Smibert R. A., Krieg N. R. (2007). Phenotypic characterization and the principles of comparative systematics, in Methods for General and Molecular Microbiology, 3rd Edn., eds Reddy C. A., Beveridge T. J., Breznak J. A., Marzluf G. A., Schmidt T. M., Snyder L. R. (Washington, DC: ASM Press; ), 330–393. 10.1128/9781555817497.ch15 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Usha R., Ananthaselvi P., Venil C. K., Palaniswamy M. (2010). Antimicrobial and antiangiogenesis activity of Streptomyces parvulus KUAP106 from Mangrove Soil. Eur. J. Biol. Sci. 2, 77–83. [Google Scholar]

- Wang X. H., Zhang C., Yang L. L., Gomes-Laranjo J. (2011). Production of dragon's blood in Dracaena cochinchinensis plants by inoculation of Fusarium proliferatum. Plant Sci. 180, 292–299. 10.1016/j.plantsci.2010.09.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X. H., Zhang C. H., Wang Y., Gomes-Laranjo J. (2010). Screen of micro-organisms for inducing the production of dragon's blood by leaf of Dracaena cochinchinensis. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 51, 504–510. 10.1111/j.1472-765X.2010.02921.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu P., Li W. J., Tang S. K., Zhang Y. Q., Chen G. Z., Chen H. H., et al. (2005). Naxibacter alkalitolerans gen. nov., sp. nov., a novel member of the family 'Oxalobacteraceae' isolated from China. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 55, 1149–1153. 10.1099/ijs.0.63407-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y. Q., Liu H. Y., Chen J., Yuan L. J., Sun W., Zhang L. X., et al. (2010). Diversity of culturable actinobacteria from Qinghai-Tibet plateau, China. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 98, 213–223. 10.1007/s10482-010-9434-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.