Abstract

Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) remains challenging in patients who have undergone surgical reconstruction of the intestine. Recently, many studies have reported that balloon-enteroscope-assisted ERCP (BEA-ERCP) is a safe and effective procedure. However, further improvements in outcomes and the development of simplified procedures are required. Percutaneous treatment, Laparoscopy-assisted ERCP, endoscopic ultrasound-guided anterograde intervention, and open surgery are effective treatments. However, treatment should be noninvasive, effective, and safe. We believe that these procedures should be performed only in difficult-to-treat patients because of many potential complications. BEA-ERCP still requires high expertise-level techniques and is far from a routinely performed procedure. Various techniques have been proposed to facilitate scope insertion (insertion with percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage (PTBD) rendezvous technique, Short type single-balloon enteroscopes with passive bending section, Intraluminal injection of indigo carmine, CO2 inflation guidance), cannulation (PTBD or percutaneous transgallbladder drainage rendezvous technique, Dilation using screw drill, Rendezvous technique combining DBE with a cholangioscope, endoscopic ultrasound-guided rendezvous technique), and treatment (overtube-assisted technique, Short type balloon enteroscopes) during BEA-ERCP. The use of these techniques may allow treatment to be performed by BEA-ERCP in many patients. A standard procedure for ERCP yet to be established for patients with a reconstructed intestine. At present, BEA-ERCP is considered the safest and most effective procedure and is therefore likely to be recommended as first-line treatment. In this article, we discuss the current status of BEA-ERCP in patients with surgically altered gastrointestinal anatomy.

Keywords: Balloon enteroscopy, Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography, Altered gastrointestinal anatomy, Balloon-enteroscope-assisted endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography

Core tip: Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) remains challenging in patients with reconstructed intestine. Recently, many studies have reported that balloon-enteroscope-assisted ERCP (BEA-ERCP) is a safe and effective procedure. However, further improvements in outcomes and the development of simplified procedures are required. Various techniques have been proposed to facilitate scope insertion, cannulation, and treatment during BEA-ERCP. We discuss the current status of BEA-ERCP in patients with surgically altered gastrointestinal anatomy and introduce the techniques that are considered necessary in order to improve the outcomes.

INTRODUCTION

Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) has become an essential endoscopic technique for the diagnosis and treatment of pancreatobiliary disease. The success rate of ERCP in patients with normal gastrointestinal anatomy has been estimated to be 95%[1]. However, ERCP is challenging after intestinal reconstruction, particularly in patients who have undergone Billroth-II (B-II) reconstruction with Braun’s anastomosis and a long afferent limb, Roux-en-Y (R-Y) reconstruction (R-Y reconstruction with total gastrectomy, R-Y reconstruction with gastric bypass, R-Y reconstruction with pancreaticoduodenectomy, R-Y reconstruction with pylorus-preserving pancreaticoduodenectomy, R-Y reconstruction with hepaticojejunostomy, etc.) or pancreaticoduodenectomy (Whipple resection, Child’s operation, etc.). ERCP has been performed using a side-viewing duodenoscope or a forward-viewing adult or pediatric small-caliber colonoscope in patients with a reconstructed intestine[2-4], but the results were far from satisfactory. Success or failure appeared to depend on the skill and passion of the operator, and the procedures were generally considered unrealistic. Percutaneous treatment and surgery were performed in many patients.

In 2001, double-balloon enteroscope (DBE) was reported by Yamamoto et al[5] to be an effective procedure for the diagnosis and treatment of small intestinal lesions. In 2005, DBE-assisted ERCP was first successfully by Haruta et al[6] used to treat a late anastomotic stricture in a patient who undergone biliary reconstruction by R-Y choledochojejunostomy after liver transplantation. The advent of balloon enteroscope allowed a scope to relatively easily reach the blind end (the papilla of Vater or bilioenteric or pancreatoenteric anastomosis). Subsequently, dramatic progress was made in procedures for ERCP in patients with altered gastrointestinal anatomy, and many studies have reported good outcomes with balloon-enteroscope-assisted ERCP (BEA-ERCP)[7-24] (Table 1). Recently, short-type DBE (model EI-530B, Fujifilm, Osaka, Japan) and single-balloon enteroscopes (SBE; model SIF-Y0004, SIF-Y0004-V01, Olympus Medical Systems, Tokyo, Japan) have been developed and used to perform ERCP in patients with surgically altered gastrointestinal anatomy[7-14,21-23,25]. Between January 1, 2012 and December 31, 2012, a total of 7488 sessions of ERCP were performed in 11 high-volume centers in Japan; 490 (6.1%) of these sessions were performed in patients who had undergone intestinal reconstruction surgery[26]. Although the demand is increasing, BEA-ERCP still requires high expertise-level techniques and is far from a routinely performed procedure. In this article, we discuss the current status of BEA-ERCP in patients with surgically altered gastrointestinal anatomy.

Table 1.

Studies of balloon-enteroscope-assisted endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography n (%)

| Ref. | Enteroscope and No. of patients (prodecures) | Anatomy | Reaching the blind end | Diagnostic success | Therapeutic success | Complications |

| Raithel et al[15] | DBE 31 (86) | R-Y (24) | 23 (74) | 21 (91.3) | 21 (91.3) | 5 (5.8) |

| (CDJ or HJ:19, TG:5) | Perforation (2) | |||||

| B-II (6) | Bleeding (1) | |||||

| HJ (1) | Pancreatitis (2) | |||||

| Schreiner et al[24] | DBE 26 (26) | R-Y GB(26) | 23 (72) | 19 (83) | 19 (100) | 1 (3.1) |

| Pancreatitis (1) | ||||||

| Pohl et al[17] | DBE 15 (25) | R-Y CDJ (15) | 21 (84) | 21 (100) | 16 (100) | 0 (0) |

| Shimatani et al[11] | sDBE 68 (103) | R-Y TG (36) | 100 (97) | 98 (98) | 98 (100) | 5 (5) |

| B-II (17) | Perforation [5 (surgery:1)] | |||||

| PD (15) | ||||||

| Siddiqui et al[12] | sDBE 79 (79) | R-Y (53) | 23 (74) | 21 (91.3) | 21 (91.3) | 4 (5) |

| (GB:39, GJ:5, HJ:4,PJ:3, CDJ:2) | Pancreatitis (3) | |||||

| PD (20) | Bleeding (1) | |||||

| B-II (3) | ||||||

| HJ (3) | ||||||

| Osoegawa et al[13] | sDBE 28 (47) | R-Y (25) | 45 (96) | 40 (89) | 40 (100) | 1 (2.1) |

| B-II (19) | Perforation (1) requiring surgery | |||||

| PD (3) | ||||||

| Cho et al[14] | sDBE 20 (29) | R-Y (13) | 25 (86) | 24 (96) | 24 (100) | 0 (0) |

| (HJ:7, GJ:5, EJ:1) | ||||||

| B-II (6) | ||||||

| PD (1) | ||||||

| Tsujino et al[21] | sDBE 6 (12) | HJ (7) | 12 (100) | 12 (100) | 12 (100) | 2 (16.6) |

| R-Y gastrectomy (3) | Cholangitis (1) | |||||

| PD (2) | Perforation (1) | |||||

| Shah et al[18] | DBE 27 (27) | R-Y GB (15) | 20 (74) | 17 (85) | 17 (85) | NA (complications not separately described according to procedure) |

| SBE 45 (45) | non R-Y GB (12) | 31 (69) | 27 (87) | 27 (87) | ||

| R-Y GB (22) | ||||||

| non R-Y GB (23) | ||||||

| Chua et al[16] | DBE 16 (21) | R-Y with OLT(12) | DBE 12 (75)1 | DBE 12 (100)1 | DBE 7 (78)1 | 1 (5.55)1 |

| SBE 2 (3) | R-Y HJ (6) | SBE 2 (100)1 | SBE 2 (100)1 | SBE 2 (100)1 | Cholangitis (1) | |

| B-II (1) | ||||||

| PD (1) | ||||||

| Kasai procedure (1) | ||||||

| Azeem et al[20] | SBE 36 (58) | R-Y with OLT (36) | 53 (91.4) | 44 (75.9) | 41 (100) | 0 (0) |

| Saleem et al[19] | SBE 50 (56) | R-Y HJ (41) | 42 (75) | 39 (93) | 21 (91.3) | 0 (0) |

| R-Y GB (15) | ||||||

| Itokawa et al[22] | SBE 44 (44) | R-Y HJ (28) | 54 (87) | 53 (98) | 37 (92.5) | 1 (1.6) |

| sSBE 16 (16) | Whipple resection (16) | Bleeding (1) | ||||

| sDBE 2 (2) | ||||||

| Yamauchi et al[7] | sSBE 22 (31) | R-Y gastrectomy (21) | 19 (91) | 17 (90) | 15 (94) | 4 (12.9) |

| R-Y HJ (2) | 2 (100) | 2 (100) | 2 (100) | Pancreatitis (2) | ||

| B-II (8) | 7 (88) | 6 (86) | 5 (100) | Perforation (1) | ||

| Bleeding (1) | ||||||

| 2Iwai et al[9] | SBE N/A (28) | R-Y (71) | 25 (89) | 19 (76) | 17 (94) | 8 (8.8) |

| sSBE N/A (62) | B-II (19) | 57 (92) | 51 (89) | 48 (94) | Pancreatitis (5) | |

| Perforation (2) | ||||||

| Bleeding (1) | ||||||

| Shimatani et al[10] | sSBE 26 (26) | R-Y (12) | 24 (92.3) | 22 (91.7) | 22 (100) | 1 (3.8) |

| (HJ:8, gastrectomy:4) | Hematoma (1) | |||||

| PD (9) | ||||||

| B-II (3) | ||||||

| Other (2) | ||||||

| Kawamura et al[23] | sSBE 18 (27) | R-Y (25) | 24 (89) | 20 (74) | 19 (70) | 0 (0) |

| (gastrectomy:15, CDJ:10 ) | ||||||

| B-II (2) | ||||||

| Obana et al[8] | sSBE 8 (12) | R-Y gastrectomy (8) | 7 (87.5)1 | 5 (71.4)1 | 5 (71.4)1 | 0 (0) |

Date per patient;

Concluding the results of Yamauchi et al[7]. B-II: Billroth-II; CDJ: Choledochojejunostomy; (s)DBE: (Short type) double balloon enteroscope; EJ: Esophagojejunostomy; GJ: Gastrojejunostomy; HJ: Hepaticojejunostomy; NA: Not available or not applicable; OLT: Orthotopic liver transplant; PD: Pancreatoduodenostomy; PJ: Pancreaticojejunostomy; R-Y: Roux-en-Y; (s)SBE: (Short type) single balloon enteroscope; TG: Total gastrectomy.

CHALLENGES OF ERCP IN PATIENTS WITH ALTERED GASTROINTESTINAL ANATOMY

Challenge of reaching the blind end

The first challenge is whether the papilla of Vater or bilioenteric or pancreatoenteric anastomosis (hepaticojejunostomy or pancreaticojejunostomy) can be reached. The degree of difficulty differs depending on the reconstruction method. There main reasons for difficulty in reaching the blind end are as follows: (1) a conventional endoscope cannot reach the blind end owing to the long length of the reconstructed intestine; (2) passage of the endoscope is often precluded by postoperative adhesions or sharp bends of the reconstructed intestine; and (3) because a postoperative reconstructed intestine is like a labyrinth, it is difficult to identify the afferent limb leading to the blind end.

The use of a tip cap helps to maintain a proper distance between the scope tip and the intestine, thereby ensuring an adequate field of vision at the time of insertion. Application of abdominal compression as needed can facilitate successful insertion of the scope.

Challenge of cannulating the papilla of Vater or bilioenteric or pancreatoenteric anastomosis

After reaching the blind end, the next challenge is whether the papilla of Vater or bilioenteric or pancreatoenteric anastomosis can be successfully cannulated. Cannulation of the naive papilla is more difficult than that of a bilioenteric or pancreatoenteric anastomosis. The use of a tip cap helps to maintain a proper distance between the scope tip and the papilla of Vater or bilioenteric or pancreatoenteric anastomosis, thereby ensuring an adequate field of vision, which facilitates successful cannulation. However, cannulation is difficult when a frontal view of the papilla cannot be obtained because it faces the contralateral side after surgery or when the papilla is located within a diverticulum. When the papilla is located in a diverticulum, it is often difficult to identify without turning around the scope. Cannulation can be easily performed in many patients with a bilioenteric or pancreatoenteric anastomosis. In some patients with severe anastomotic stricture, however, the anastomosis cannot be identified, or a catheter cannot be inserted.

Challenge of therapeutic procedures

The third challenge is whether treatment can be performed. Since the introduction of balloon enteroscope, the success rate of scope insertion to the blind end has risen to higher than 80%. However, initially marketed balloon enteroscopes had a working effective length of 200 cm and a working channel diameter of 2.8 mm. Most conventional devices for ERCP were too short to be used, and complex procedures could not be performed. The advent of short-type DBE (models EC-450B15 and EI-530B; working length, 152 cm; working channel diameter, 2.8 mm; Fujifilm, Osaka, Japan) allowed most conventional devices to be used. However, several problems remain to be solved, such as wire-guided devices cannot be used, and only stents of a limited diameter can be inserted.

Innovations and techniques

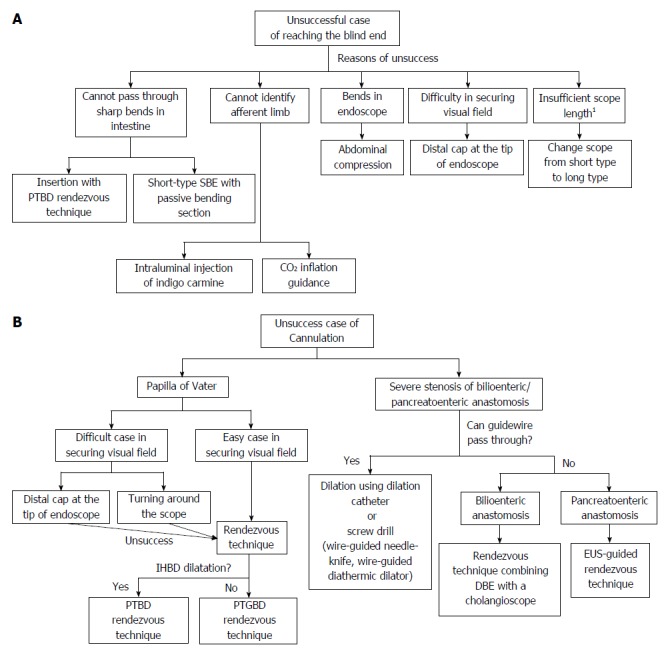

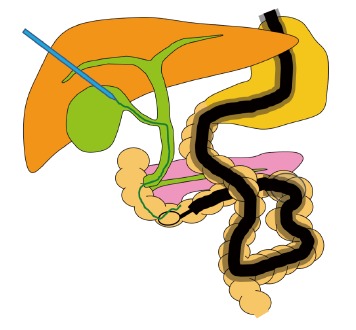

Innovations and techniques for reaching the blind end: Innovations and techniques for passing through sharp bends in the intestine and anastomoses (Figure 1A). Insertion with percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage (PTBD) rendezvous technique (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Innovations and techniques for reaching the blind end (A) and for cannulation of papilla of Vater/bilioenteric or pancreatoenteric anastomosis (B). 1If short-type balloon endoscope was used. PTBD: Percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage; SBE: Single-balloon enteroscopes.

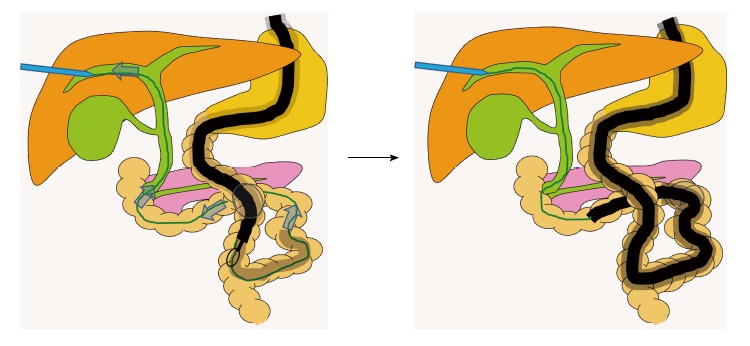

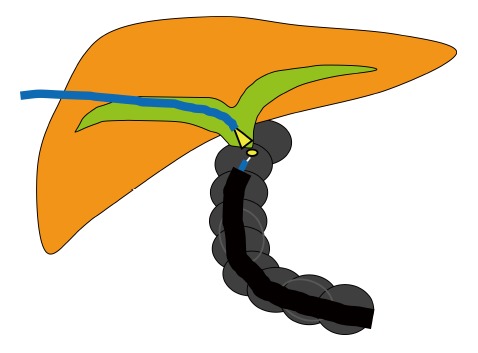

Figure 2.

Insertion with percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage rendezvous technique.

Itoi et al[27] described a method for inserting a scope into the blind end, using a rendezvous technique. A guidewire is passed in an antegrade fashion through the major papilla after needle puncture by the percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage technique. A hydrophilic guidewire with an ERCP catheter is advanced in an antegrade direction beyond the Roux-en-Y limb. After firmly grasping the guidewire with snare forceps, it is pulled out of the body, allowing the enteroscope to advance to the papilla.

Short-type SBE equipped with a passive bending, high-force-transmission insertion tube. Shimatani et al[10] reported the usefulness of a prototype short-type SBE equipped with a passive bending, high-force-transmission insertion tube (SIF-Y0004-V01; working length, 1520 mm; working channel diameter, 3.2 mm; Olympus Medical Systems, Tokyo, Japan). SBE-assisted ERCP (SBE-ERCP) was performed in 26 patients who had surgically altered gastrointestinal anatomy (R -Y reconstruction in 12, Billroth II gastrectomy in 3, pancreatoduodenectomy in 4, pylorus-preserving pancreatoduodenectomy in 5, and others in 2). The success rate of reaching the blind end was 92.3%. Passive bending, high-force-transmission insertion tubes are already clinically used in colonoscopes and are considered to facilitate passage through sharp bends in the intestine. Such tubes are also expected to be effective for BEA-ERCP.

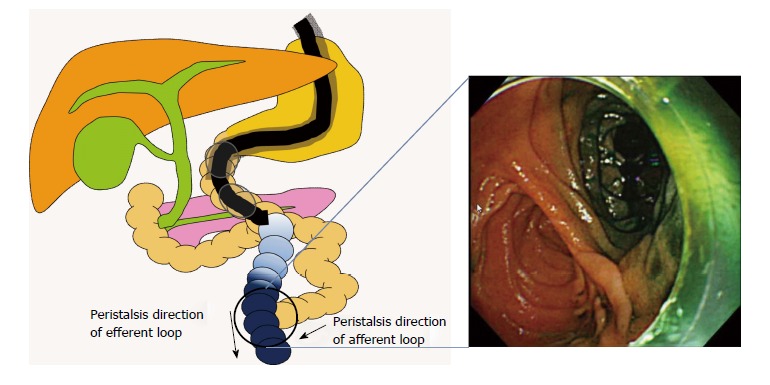

Innovations and techniques for identification of the afferent limb (Figure 1A). Intraluminal injection of indigo carmine (Figure 3). Yano et al[28] described the intraluminal injection of indigo carmine in patients with an R-Y anastomosis who underwent double-balloon ERCP. In the second portion of the duodenum or distal to the esophagojejunostomy, indigo carmine is injected into the lumen, and the scope is inserted. Intestinal peristalsis moves the indigo carmine dye distally. However, because peristalsis normally proceeds from the blind end to the distal colon, indigo carmine easily flows into the efferent limb, with little flow into the afferent limb. The afferent limb can thus be identified on the basis of the presence or absence of indigo carmine. The afferent limb was correctly identified in 80% of patients with an R-Y anastomosis.

Figure 3.

Intraluminal injection of indigo carmine.

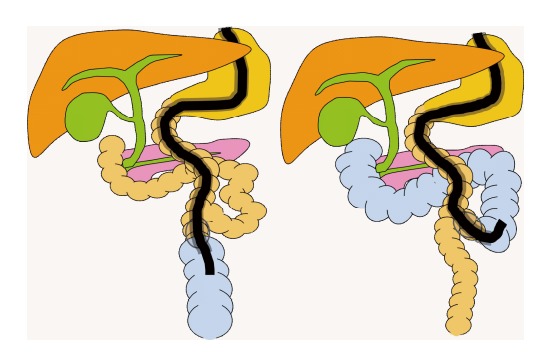

CO2 inflation guidance (Figure 4). Iwai et al[9] evaluated the usefulness of a carbon dioxide inflation guidance for identifying the afferent loop. After reaching the intestinal anastomosis, the scope was inserted into either the afferent loop or efferent loop. Next, the balloon was inflated and then insufflated with carbon dioxide. The direction of the insufflated intestine was confirmed radiographically. If the scope is placed into the afferent loop, the blind end is depicted, and the direction of movement becomes clearer.

Figure 4.

CO2 inflation guidance.

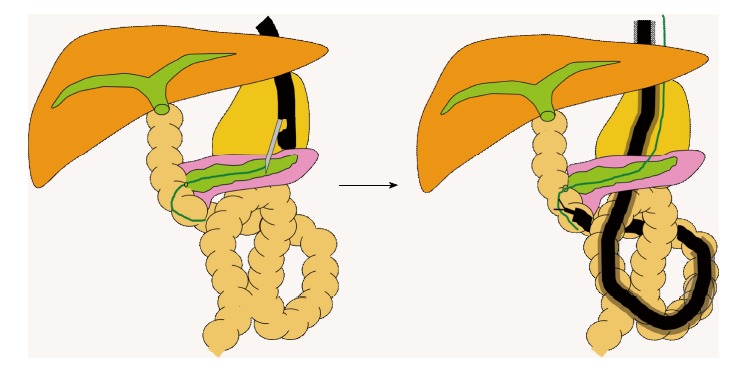

Innovations and techniques for cannulation: Rendezvous technique for PTBD or percutaneous transgallbladder drainage (Figure 1B and Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Rendezvous technique for percutaneous transgallbladder drainage.

If transpapillary cannulation is difficult, use of the rendezvous technique after PTBD can facilitate cannulation. However, in some patients with surgically altered gastrointestinal anatomy, the common bile duct is dilated after surgery, whereas the intrahepatic bile ducts are not. Okuno et al[29] reported the usefulness and safety of the percutaneous transgallbladder rendezvous technique in such patients. In this technique, percutaneous puncture of the gallbladder is performed, and a guidewire is manipulated in an antegrade fashion through the gallbladder, cystic duct, common bile duct, papilla, and duodenum. Cannulation is then performed by the rendezvous technique. The percutaneous transgallbladder rendezvous technique was successfully performed in all 6 patients studied. One patient had mild pancreatitis. However, puncture was not associated with any complications.

Cannulation in patients with severe stricture of a bilioenteric or pancreatoenteric anastomosis. Soehendra Stent Retriever®. Tsutsumi et al[30] reported that a Soehendra Stent Retriever® (Cook Medical Inc., Winston-Salem, NC, United States) was useful for dilating a severe stenosis of a bilioenteric or pancreatoenteric anastomosis in 2 patients.

Rendezvous technique combining DBE with a SpyGlass® direct visualization system (Figure 6). Shimatani et al[31] assessed the usefulness of a rendezvous technique combining DBE with a SpyGlass® direct visualization system (SDVS; Boston Scientific Corp., Natick, MA, United States) in a patient in whom a wire could not be passed in a retrograde or antegrade direction through a severe stenosis of a bilioenteric anastomosis. The SDVS was inserted via the percutaneous transhepatic colangiodrainage route and functioned as a light source. An incision was made with a needle knife towards the light of the SDVS, facilitating passage through the stenosis and accurate incision into the biliary duct. Guidewires were then advanced through the anastomotic stenosis and dilatation was successfully performed.

Figure 6.

Rendezvous technique combining double-balloon enteroscope with a SpyGlass® direct visualization system.

EUS-guided rendezvous technique (Figure 7). Itoi et al[32] used an endoscopic ultrasound (EUS)-guided rendezvous technique to treat severe stenosis of a pancreatoenteric anastomosis. In contrast to the bile duct, percutaneous puncture of the pancreatic duct is not feasible. The pancreatic duct was therefore accessed by transgastrically puncturing the main duct with a 19-gauge needle under EUS guidance. The wire was then passed from the pancreaticojejunostomy to the intestine. The anastomotic stricture was thus treated by the rendezvous technique.

Figure 7.

Endoscopic ultrasound-guided rendezvous technique.

In patients in whom a catheter cannot pass through a stricture despite successful insertion of a guidewire, a wire-guided needle-knife (MicroKnife XL sphincterotome, Boston Scientific)[33] or a 6F wire-guided diathermic dilator (Cysto-Gastro-Set; Endo-Flex, GmbH, Voerde, Germany)[34] may be useful (Figure 1B).

Innovations and techniques of procedures: Overtube-assisted technique - Itoi et al[35] reported an overtube-assisted technique for SBE-assisted ERCP in which the SBE is replaced with a conventional forward-viewing upper endoscope. After a long-type SBE reaches the blind end, the scope is removed, while allowing the overtube to remain in the intestine. Then, an aperture is made in the overtube, and the conventional endoscope is inserted. If scope replacement is successful, conventional devices used to perform ERCP can be used. The scope was successfully replaced in 11 of 12 patients.

Short-type balloon endoscope - Although the overtube-assisted technique is an effective procedure, switching scopes is sometimes difficult in patients with multiple loops or severe adhesions. A short-type DBE (working length, 152 cm; working channel diameter, 2.8 mm) was therefore developed to perform ERCP and has been reported to be useful[11-14]. Because the working length is 152 cm, conventional devices can be used to perform ERCP. However, because the working channel diameter is only 2.8 mm, wire-guided devices and devices with a diameter of 8-French or greater could not be used. To overcome these drawbacks, a short-type SBE with a working length of 152 cm and a working channel diameter of 3.2 mm was developed. This scope has the advantage that the larger working channel allows the use of wire-guided devices and devices up to 8.5-Fr in diameter. The success rate of reaching the blind end with a short-type SBE is comparable to that with a long-type SBE, and several advantages have been reported[8,9]. However, a short-type balloon endoscope is not yet commercially available.

Innovations and techniques for patients in whom reaching the blind end and treatment are difficult with a balloon endoscope: Long-limb R-Y gastric bypass with a reconstructed afferent limb of 100 cm or longer is generally performed in obese patients to promote weight loss. It is difficult to reach the blind end even with the use of a balloon enteroscope in patients who have undergone this procedure. Schreiner et al[24] reported that therapeutic success rate of BEA-ERCP was 88% in patients with a total small bowel length of less than 150 cm, as compared with only 33% for a length of 150 to 225 cm, and 0% for a length greater than 225 cm. Reaching the blind end with a short-type balloon endoscope, capable of performing sophisticated treatment procedures, is thus expected to be difficult. However, even if the blind end can be reached with a long-type balloon endoscope, only a limited number of procedures can be performed; high-level treatment is thus not feasible. A recent study estimated that 50 billion adults or 10% to 14% of the worldwide population met the diagnostic criteria for obesity[36]. Further growth of the obese population is expected to be accompanied by increasing numbers of patients who undergo long-limb R-Y gastric bypass to reduce body weight.

Percutaneous-assisted transprosthetic endoscopic therapy - Law et al[37] and Baron et al[38] performed percutaneous-assisted transprosthetic endoscopic therapy in patients who had undergone R-Y gastric bypass. Even if a long-type balloon endoscope can reach the papilla of Vater, high-level treatment procedures are difficult to perform in some patients. In such patients, retrograde percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) is performed after reaching the stomach. Then, a self-expandable metal stent (SEMS) is deployed within the gastrostomy tract. The metal stent is dilated with the use of a balloon. A duodenoscope is advanced through the percutaneous metal stent in an antegrade manner to reach the duodenal papilla. Conventional treatment can then be performed. In contrast to gastrostomy-assisted transgastric ERCP, the SEMS can remain in situ after PEG to perform subsequent procedures without waiting for fistula formation. Treatment can therefore be done on the same day. Percutaneous-assisted transprosthetic endoscopic therapy was performed in 5 patients. The treatment success rate was 100%, and only 1 patient had complications. The mean procedure time was 97 min. If the PEG tube is left in place, additional treatment procedures can be done. Flynn et al[39] compared gastrostomy-assisted transgastric ERCP (24 sessions) with SBE-ERCP (35 sessions) and reported that the rate of reaching the blind end was significantly higher for transgastric ERCP (100%) than for SBE-ERCP (77%, P < 0.02). The therapeutic success rate was also significantly higher for transgastric ERCP (96%) than for SBE-ERCP (64%, P < 0.01). However, the rate of complications was significantly higher for transgastric ERCP (38%) than for SBE-ERCP (9%, P < 0.08). A drawback of transgastric ERCP is that treatment cannot be performed during the period between gastrostomy placement and gastrostomy maturation; emergency treatment is also not possible. Percutaneous-assisted transprosthetic endoscopy has resolved these problems.

Laparoscopy-assisted ERCP (LA-ERCP) - Because percutaneous-assisted transprosthetic endoscopic therapy requires retrograde insertion of a balloon enteroscope into the stomach, the blind end cannot be reached in some patients. LA-ERCP was developed to overcome this drawback. A route for direct insertion of an endoscope into the stomach or the jejunum is made under laparoscopic guidance. Then, an endoscope is inserted through the access port of the laparoscope and advanced to the blind end. This procedure is performed in an operating room and allows conventional ERCP as well as emergency treatment to be performed. A retrospective study comparing LA-ERCP with BEA-ERCP[24] showed that LA-ERCP was superior to BEA-ERCP in terms of papilla identification (100% vs 72%, P < 0.005), cannulation rate (100% vs 59%, P < 0.001), and therapeutic success (100% vs 59%, P < 0.001). The study recommended that laparoscopy-assisted ERCP should be initially performed in patients in whom the length of the Roux limb + ligament of Treitz to the jejunojejunal anastomosis is 150 cm or longer, whereas BE-ERCP should be performed in patients with a length of less than 150 cm. However, LA-ERCP is associated with a high rate of complications (13% to 20%) and a longer mean procedure time (89 to 200 min)[24,40,41]. Therefore, close cooperation with surgeons and anesthesiologists is required.

EUS-guided anterograde intervention - Weilert et al[42] performed EUS-guided antegrade stone removal in 6 patients. The following technique was used. First, EUS-guided fine-needle aspiration (FNA) puncture into an intrahepatic bile duct is performed. EUS-guided cholangiography is then done to confirm the bile duct. A guidewire is advanced from the bile duct to the intestine. Subsequently, the transhepatic-transgastric access tract is dilated, and the papilla is dilated with a balloon in an antegrade manner. Finally, biliary stones are pushed out from the papilla in an antegrade fashion, using a balloon catheter. The success rate of cholangiography was 100%, and the stone extraction success rate was 67%. One patient had complications.

CONCLUSION

BEA-ERCP has been reported to be safe and have good outcomes in patients with surgically altered gastrointestinal anatomy and is thus considered a promising procedure. As described above, the development of various techniques and new models of endoscopes has allowed more reliable, higher-quality therapy to be performed, even in patients in whom difficulty is encountered in reaching the blind end or in performing treatment. Percutaneous treatment, LA-ERCP, EUS-guided anterograde intervention, and open surgery are effective treatments. Ideally, however, treatment should be noninvasive, effective, and safe. The procedures described above should be performed only in difficult-to-treat patients because of many potential complications. At present, there is no standard treatment for ERCP in patients who have undergone intestinal reconstruction. We believe that BEA-ERCP should be considered as an initial treatment in such patients.

Footnotes

Conflict-of-interest: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Peer-review started: January 20, 2015

First decision: March 10, 2015

Article in press: May 7, 2015

P- Reviewer: Calabrese C, Grundmann O, Soares RLS S- Editor: Ma YJ L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wang CH

References

- 1.Freeman ML, Guda NM. ERCP cannulation: a review of reported techniques. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;61:112–125. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(04)02463-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hintze RE, Adler A, Veltzke W, Abou-Rebyeh H. Endoscopic access to the papilla of Vater for endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography in patients with billroth II or Roux-en-Y gastrojejunostomy. Endoscopy. 1997;29:69–73. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1004077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Elton E, Hanson BL, Qaseem T, Howell DA. Diagnostic and therapeutic ERCP using an enteroscope and a pediatric colonoscope in long-limb surgical bypass patients. Gastrointest Endosc. 1998;47:62–67. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(98)70300-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wright BE, Cass OW, Freeman ML. ERCP in patients with long-limb Roux-en-Y gastrojejunostomy and intact papilla. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;56:225–232. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(02)70182-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yamamoto H, Sekine Y, Sato Y, Higashizawa T, Miyata T, Iino S, Ido K, Sugano K. Total enteroscopy with a nonsurgical steerable double-balloon method. Gastrointest Endosc. 2001;53:216–220. doi: 10.1067/mge.2001.112181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Haruta H, Yamamoto H, Mizuta K, Kita Y, Uno T, Egami S, Hishikawa S, Sugano K, Kawarasaki H. A case of successful enteroscopic balloon dilation for late anastomotic stricture of choledochojejunostomy after living donor liver transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2005;11:1608–1610. doi: 10.1002/lt.20623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yamauchi H, Kida M, Okuwaki K, Miyazawa S, Iwai T, Takezawa M, Kikuchi H, Watanabe M, Imaizumi H, Koizumi W. Short-type single balloon enteroscope for endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography with altered gastrointestinal anatomy. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:1728–1735. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i11.1728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Obana T, Fujita N, Ito K, Noda Y, Kobayashi G, Horaguchi J, Koshita S, Kanno Y, Ogawa T, Hashimoto S, et al. Therapeutic endoscopic retrograde cholangiography using a single-balloon enteroscope in patients with Roux-en-Y anastomosis. Dig Endosc. 2013;25:601–607. doi: 10.1111/den.12039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Iwai T, Kida M, Yamauchi H, Imaizumi H, Koizumi W. Short-type and conventional single-balloon enteroscopes for endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography in patients with surgically altered anatomy: single-center experience. Dig Endosc. 2014;26 Suppl 2:156–163. doi: 10.1111/den.12258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shimatani M, Takaoka M, Ikeura T, Mitsuyama T, Okazaki K. Evaluation of endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography using a newly developed short-type single-balloon endoscope in patients with altered gastrointestinal anatomy. Dig Endosc. 2014;26 Suppl 2:147–155. doi: 10.1111/den.12283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shimatani M, Matsushita M, Takaoka M, Koyabu M, Ikeura T, Kato K, Fukui T, Uchida K, Okazaki K. Effective “short” double-balloon enteroscope for diagnostic and therapeutic ERCP in patients with altered gastrointestinal anatomy: a large case series. Endoscopy. 2009;41:849–854. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1215108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Siddiqui AA, Chaaya A, Shelton C, Marmion J, Kowalski TE, Loren DE, Heller SJ, Haluszka O, Adler DG, Tokar JL. Utility of the short double-balloon enteroscope to perform pancreaticobiliary interventions in patients with surgically altered anatomy in a US multicenter study. Dig Dis Sci. 2013;58:858–864. doi: 10.1007/s10620-012-2385-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Osoegawa T, Motomura Y, Akahoshi K, Higuchi N, Tanaka Y, Hisano T, Itaba S, Gibo J, Yamada M, Kubokawa M, et al. Improved techniques for double-balloon-enteroscopy-assisted endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:6843–6849. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i46.6843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cho S, Kamalaporn P, Kandel G, Kortan P, Marcon N, May G. ‘Short’ double-balloon enteroscope endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography in patients with a surgically altered upper gastrointestinal tract. Can J Gastroenterol. 2011;25:615–619. doi: 10.1155/2011/354546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Raithel M, Dormann H, Naegel A, Boxberger F, Hahn EG, Neurath MF, Maiss J. Double-balloon-enteroscopy-based endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography in post-surgical patients. World J Gastroenterol. 2011;17:2302–2314. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v17.i18.2302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chua TJ, Kaffes AJ. Balloon-assisted enteroscopy in patients with surgically altered anatomy: a liver transplant center experience (with video) Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;76:887–891. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2012.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pohl J, May A, Aschmoneit I, Ell C. Double-balloon endoscopy for retrograde cholangiography in patients with choledochojejunostomy and Roux-en-Y reconstruction. Z Gastroenterol. 2009;47:215–219. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1027800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shah RJ, Smolkin M, Yen R, Ross A, Kozarek RA, Howell DA, Bakis G, Jonnalagadda SS, Al-Lehibi AA, Hardy A, et al. A multicenter, U.S. experience of single-balloon, double-balloon, and rotational overtube-assisted enteroscopy ERCP in patients with surgically altered pancreaticobiliary anatomy (with video) Gastrointest Endosc. 2013;77:593–600. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2012.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Saleem A, Baron TH, Gostout CJ, Topazian MD, Levy MJ, Petersen BT, Wong Kee Song LM. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography using a single-balloon enteroscope in patients with altered Roux-en-Y anatomy. Endoscopy. 2010;42:656–660. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1255557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Azeem N, Tabibian JH, Baron TH, Orhurhu V, Rosen CB, Petersen BT, Gostout CJ, Topazian MD, Levy MJ. Use of a single-balloon enteroscope compared with variable-stiffness colonoscopes for endoscopic retrograde cholangiography in liver transplant patients with Roux-en-Y biliary anastomosis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2013;77:568–577. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2012.11.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tsujino T, Yamada A, Isayama H, Kogure H, Sasahira N, Hirano K, Tada M, Kawabe T, Omata M. Experiences of biliary interventions using short double-balloon enteroscopy in patients with Roux-en-Y anastomosis or hepaticojejunostomy. Dig Endosc. 2010;22:211–216. doi: 10.1111/j.1443-1661.2010.00985.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Itokawa F, Itoi T, Ishii K, Sofuni A, Moriyasu F. Single- and double-balloon enteroscopy-assisted endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography in patients with Roux-en-Y plus hepaticojejunostomy anastomosis and Whipple resection. Dig Endosc. 2014;26 Suppl 2:136–143. doi: 10.1111/den.12254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kawamura T, Uno K, Suzuki A, Mandai K, Nakase K, Tanaka K, Yasuda K. Clinical usefulness of a short-type, prototype single-balloon enteroscope for endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography in patients with altered gastrointestinal anatomy: preliminary experiences. Dig Endosc. 2015;27:82–86. doi: 10.1111/den.12322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schreiner MA, Chang L, Gluck M, Irani S, Gan SI, Brandabur JJ, Thirlby R, Moonka R, Kozarek RA, Ross AS. Laparoscopy-assisted versus balloon enteroscopy-assisted ERCP in bariatric post-Roux-en-Y gastric bypass patients. Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;75:748–756. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2011.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yane K, Katanuma A, Osanai M, Maguchi H, Takahashi K, Kin T, Takaki R, Matsumoto K, Gon K, Matsumori T, et al. Successful removal of a pancreatic duct stone in a patient with Whipple resection, using a short single-balloon enteroscope with a transparent hood. Endoscopy. 2014;46 Suppl 1 UCTN:E86–E87. doi: 10.1055/s-0033-1344832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Katanuma A, Isayama H. Current status of endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography in patients with surgically altered anatomy in Japan: questionnaire survey and important discussion points at Endoscopic Forum Japan 2013. Dig Endosc. 2014;26 Suppl 2:109–115. doi: 10.1111/den.12247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Itoi T, Ishii K, Sofuni A, Itokawa F, Kurihara T, Tsuchiya T, Tsuji S, Umeda J, Moriyasu F. Single Balloon Enteroscopy-Assisted ERCP Using Rendezvous Technique for Sharp Angulation of Roux-en-Y Limb in a Patient with Bile Duct Stones. Diagn Ther Endosc. 2009;2009:154084. doi: 10.1155/2009/154084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yano T, Hatanaka H, Yamamoto H, Nakazawa K, Nishimura N, Wada S, Tamada K, Sugano K. Intraluminal injection of indigo carmine facilitates identification of the afferent limb during double-balloon ERCP. Endoscopy. 2012;44 Suppl 2 UCTN:E340–E341. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1309865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Okuno M, Iwashita T, Yasuda I, Mabuchi M, Uemura S, Nakashima M, Doi S, Adachi S, Mukai T, Moriwaki H. Percutaneous transgallbladder rendezvous for enteroscopic management of choledocholithiasis in patients with surgically altered anatomy. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2013;48:974–978. doi: 10.3109/00365521.2013.805812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tsutsumi K, Kato H, Sakakihara I, Yamamoto N, Noma Y, Horiguchi S, Harada R, Okada H, Yamamoto K. Dilation of a severe bilioenteric or pancreatoenteric anastomotic stricture using a Soehendra Stent Retriever. World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2013;5:412–416. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v5.i8.412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shimatani M, Takaoka M, Ikeura T, Mitsuyama T, Kato K, Okazaki K. Rendezvous technique: double-balloon endoscopy and SpyGlass direct visualization system in a patient with severe stenosis of a choledochojejunal anastomosis. Endoscopy. 2014;46 Suppl 1 UCTN:E275–E276. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1365785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Itoi T, Kikuyama M, Ishii K, Matsumura K, Sofuni A, Itokawa F. EUS-guided rendezvous with single-balloon enteroscopy for treatment of stenotic pancreaticojejunal anastomosis in post-Whipple patients (with video) Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;73:398–401. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2010.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gao DJ, Hu B, Pan YM, Wang TT, Wu J, Lu R, Wang SP, Shi ZM, Huang H, Wang SZ. Feasibility of using wire-guided needle-knife electrocautery for refractory biliary and pancreatic strictures. Gastrointest Endosc. 2013;77:752–758. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2012.11.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kawakami H, Kuwatani M, Kawakubo K, Eto K, Haba S, Kudo T, Abe Y, Kawahata S, Sakamoto N. Transpapillary dilation of refractory severe biliary stricture or main pancreatic duct by using a wire-guided diathermic dilator (with video) Gastrointest Endosc. 2014;79:338–343. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2013.07.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Itoi T, Ishii K, Sofuni A, Itokawa F, Tsuchiya T, Kurihara T, Tsuji S, Ikeuchi N, Umeda J, Moriyasu F. Single-balloon enteroscopy-assisted ERCP in patients with Billroth II gastrectomy or Roux-en-Y anastomosis (with video) Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:93–99. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Finucane MM, Stevens GA, Cowan MJ, Danaei G, Lin JK, Paciorek CJ, Singh GM, Gutierrez HR, Lu Y, Bahalim AN, et al. National, regional, and global trends in body-mass index since 1980: systematic analysis of health examination surveys and epidemiological studies with 960 country-years and 9·1 million participants. Lancet. 2011;377:557–567. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)62037-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Law R, Wong Kee Song LM, Petersen BT, Baron TH. Single-session ERCP in patients with previous Roux-en-Y gastric bypass using percutaneous-assisted transprosthetic endoscopic therapy: a case series. Endoscopy. 2013;45:671–675. doi: 10.1055/s-0033-1344029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Baron TH, Song LM, Ferreira LE, Smyrk TC. Novel approach to therapeutic ERCP after long-limb Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery using transgastric self-expandable metal stents: experimental outcomes and first human case study (with videos) Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;75:1258–1263. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2012.02.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Flynn MM, Tekola BD, Schirmer BD, Hallowell PT, Yeaton P, Cox DG, Gaidhane M, Shami VM, Sauer BG, Kahaleh M, et al. Gastrostomy-assisted transgastric ERCP is superior to single-balloon-enteroscope-assisted ERCP in performing therapeutic interventions but is likely associated with more complications in patients with surgically altered anatomy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2013;77:AB388. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lopes TL, Clements RH, Wilcox CM. Laparoscopy-assisted ERCP: experience of a high-volume bariatric surgery center (with video) Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;70:1254–1259. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2009.07.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gutierrez JM, Lederer H, Krook JC, Kinney TP, Freeman ML, Jensen EH. Surgical gastrostomy for pancreatobiliary and duodenal access following Roux en Y gastric bypass. J Gastrointest Surg. 2009;13:2170–2175. doi: 10.1007/s11605-009-0991-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Weilert F, Binmoeller KF, Marson F, Bhat Y, Shah JN. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided anterograde treatment of biliary stones following gastric bypass. Endoscopy. 2011;43:1105–1108. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1256961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]